Meidum pyramid

| Meidum pyramid | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

The ruins of the Meidum pyramid

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Meidum pyramid was built in three phases under the ancient Egyptian king Snefru ( 4th dynasty ) in Meidum and was the fifth highest of the ancient Egyptian pyramids . The finished structure was probably not used as the king's tomb, but served as a cenotaph (mock grave ). The current appearance of the Meidum pyramid is characterized by the ruins of the pyramid core and the rubble belt surrounding it, which means that the pyramid character is hardly recognizable.

exploration

The peculiar condition of the pyramid attracted the attention of residents and visitors early on, who referred to the building as el-haram el-kaddab (false pyramid) . A report by the Arab historian Taqi ad-Din al-Maqrizi from the 12th century describes the pyramid as a five-tiered mountain - a sign that the erosion by stone robbery and erosion was not so advanced at that time.

Frederic Louis Norden visited the building in the 18th century and reported only three visible steps. A first, brief investigation was carried out in 1799 by Napoleon's Egyptian expedition . In 1837 John Shae Perring examined and measured the structure, followed by Karl Richard Lepsius in 1843. The latter cataloged the structure under the number LXV in his list of pyramids .

Gaston Maspero finally managed to find the entrance to the base of the pyramid, but an extensive investigation was not carried out until ten years later by Flinders Petrie in collaboration with Percy Newberry and George Fraser . This investigation included both the interior of the pyramid and the structure and also unearthed the pyramid temple, the access road and a large number of private graves. A second investigation by Petrie followed, this time together with Ernest Mackay and Gerald Wainwright , in the course of which a tunnel was driven into the pyramid body, whereby ten inclined shells of the masonry of the pyramid were detected. Petrie also reported that the pyramid was still used as a quarry for local residents in his time.

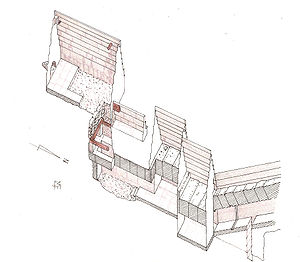

An exploration of the pyramid by Ludwig Borchardt , which lasted only a few days , produced such a wealth of new information that he was able to publish an entire book that is still highly regarded today. The excavations also revealed the remains of a ramp construction that was used to build the pyramid.

A British-American expedition under Alan Rowe investigated the pyramid in the 1920s, but the structure received little attention for over 50 years until Egyptian archaeologists under Ali el-Kholi examined the rubble belt of the ruin in the 1970s .

In 1999, Gilles Dormion and Jean-Yves Verd'hurt found previously unknown pressure relief chambers and ducts above the duct chambers and the sloping passage during endoscopic examinations.

Theories on the state of the pyramid

A theory about the condition of the pyramid that was very popular at times, but not recognized within Egyptological research, is that of the physicist Kurt Mendelssohn that a disaster occurred during construction and that the outer jacket and parts of the outer stone layers were used as an extension over an originally smaller building had slipped, revealing the inner structure of the pyramid. This theory could already be refuted at the time of its publication by the fact that graffiti originating from the New Kingdom was found in the buried pyramid temple. In addition, the deposition layers of the debris belt do not correspond to a one-off sliding process, but rather to a formation over a longer period of time. The theory also contradicts the fact that when the rubble was cleared away later remains were found, but no ropes, wood or even workers' corpses from the 4th dynasty. Therefore, today it is generally assumed that the cladding will slide off gradually, probably during the stone robbery.

More recently it has also been assumed by George Johnson that the Meidum pyramid was never completed and that the pile of rubble now visible around the pyramid was a result of the dismantling of the ramp. An existing ramp construction could also explain why the stone robbery took place here from top to bottom and not the other way around as with most of the other pyramids.

On the other hand, several visitors with graffiti in the pyramid temple, which are dated to the 18th dynasty , testify that this was still accessible up to that time and that the rubble belt did not yet exist. In addition, the inscriptions partly praise the beauty of the temple, which also indicates the integrity of the structure at this point in time. In the rubble belt around the pyramid, graves were also found, the oldest of which date from the 22nd dynasty and are about 7 m above the level of the pyramid temple, which limits the beginning of the destruction to the period between the 18th and 22nd dynasties. The systematic stone robbery therefore probably began, as with many other pyramids, at the time of Ramses II.

Assignment

For a long time it was believed that this pyramid was built by Snofru's predecessor, Huni , for which, however, there are no compelling reasons. This assignment was made solely for the reason that otherwise no Huni tomb can be assigned. However, the name of the pyramid city near the building was "Djed Sneferu" ("Sneferu is permanent") , and only texts and inscriptions were found on site that bore the name of Snefru and not that of Huni.

Akhmed Fachri's theory that the pyramid was started under Huni and completed by his successor Sneferu is not plausible given the fact that no pyramid of a ruler of the Old Kingdom was usurped by his successor . Completion of the building under Snefru is also unlikely, as the location of other pyramids shows that the kings only had the most necessary work done on the grave of their predecessor in order to guarantee a burial and a functioning cult of the dead. So far no inscriptions with Snefru's name have been found directly on the pyramid, but research based on the circumstances mentioned today assumes that the pyramid was already started by Snefru.

Construction circumstances

The Meidum pyramid was the first tomb that Sneferu had erected during his reign. He chose a site near his residence Djed Snofru near the present-day town of Meidum , which had not previously appeared as a royal necropolis .

The construction began as a regular royal tomb in the style of the step pyramids that had been built up to then , although some innovations were already planned in this phase, such as the relocation of the burial chamber from the underground into the pyramid body.

Apparently trusting a long reign, the first conversion to a larger step pyramid began after a few years. Although it was completed, Sneferu gave up the building as a tomb and, after the relocation of his residence, began building a new pyramid in Dahshur , with which the Meidum pyramid should now fulfill a function as a cenotaph .

The final conversion of the step pyramid into a real pyramid took place after a construction interruption of several years, when Sneferu in Dahshur had already started building his third pyramid . According to Stadelmann, this is due to the fact that it now represented the Kingdom of God as a royal place of worship and therefore also had to represent an image of the actual royal tomb.

The builder of the Meidum pyramid is the vizier and son of King Nefermaat , who bore the title of “head of all royal construction work” . His mastaba (M16) is a few hundred meters north of the pyramid.

The pyramid

Due to its design and building history, the Meidum pyramid is seen as a transition from the step pyramid to the real pyramid. The present-day appearance of this pyramid is that of a three-tier tower that protrudes from a heap of rubble, which is due to the breaking away of the outer shell and the step backfilling.

The building material for the core area comes from quarries about 800 m south of the pyramid.

Construction phases

Due to the very ruinous character of the building, it is easy to see today that the pyramid was built in several phases, as elements from all construction phases are exposed. In this way, the various building techniques can be identified and, through building graffiti that Petrie found on some blocks, can also be dated within the Snofrus reign.

According to Peter Jánosi , the Meidum pyramid represents an important transition from a step pyramid to a real pyramid in terms of building history: It was started as a seven- step building in the style of the 3rd dynasty , but was then completed around the fifth Level increased by another stone bowl instead of seven to eight levels. In the last years of his reign, Sneferu apparently decided to convert the pyramid into a geometrically correct pyramid with an inclination angle of 51 ° 50'35 '', which is very close to that of the Great Pyramid . And so, after its completion, the pyramid has a core in the style of the 3rd dynasty and a cladding in the form of a real pyramid from the 4th dynasty.

1st phase (E1)

The original pyramid was started with the same construction as the step pyramids of the 3rd Dynasty. It consisted of inwardly inclined layers with a slope angle of 75 ° made of local limestone , which was clad on the outside with smooth stones made of fine limestone. This first phase of construction had a base length of around 105 m and should reach a height of 71 m in seven stages. After the construction up to the fourth or fifth stage, a change of plan took place and it was expanded in a second phase.

The only construction difference to the earlier step pyramids was that some parts of the substructure were now in the pyramid body, while they were previously completely dug into the bedrock.

2nd phase (E2)

The second construction phase involved raising the pyramid by an eighth level. To this end, another layer of wall was added at an angle of inclination of 75 °, which led to a widening of the base to 120 m and a height of 85 m. The already attached cladding of the first phase remained in place during construction and was simply walled over. The new layer of the second construction phase also received the fine limestone cladding again. The step pyramid of this shape was completed around the 14th year of the reign and the building was only the second large pyramid after the Djoser pyramid that was also completed.

Despite the completion, Sneferu had two more large pyramids built in Dahshur, which suggests that he no longer planned a funeral in Meidum. Accordingly, the execution of the other components of the pyramid complex such as the mortuary temple was poor, as no death cult had to be celebrated.

3rd phase (E3)

Around the 28th or 29th year of government, the conversion of the completed step pyramid into a real pyramid began. The dating is based on construction worker inscriptions on stones of this phase, which indicate the years of the 15th, 16th and 17th cattle counts, which corresponds to the government years 30–33. The masonry of this phase was laid in horizontal layers, as was previously introduced in the upper part of the bent pyramid and the red pyramid . The cladding of the steps of the second construction phase remained intact and was walled over. The third construction phase was also clad with fine limestone from Tura , some of which has been preserved under the rubble belt. At 51 ° 50 ', the incline of the pyramid surfaces was again steeper than that of the red pyramid and thus resembles the value of the later Cheops pyramid . This expansion increased the base length to 147 m and the height of the completed pyramid to 93.5 m, making it the fifth tallest pyramid in Egypt. The total volume of the pyramid was 638,733 m³.

However, it is unclear whether the third construction phase was completed. It is possible that construction ramps were preserved, which made it easier for later stone robberies and could explain why, in contrast to most other pyramids, the stone robbery took place from top to bottom. The catastrophe theory that the new cladding slipped off during construction has now been refuted by investigations into the rubble dump.

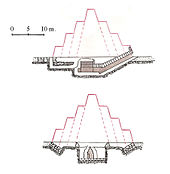

Substructure

When designing the substructure, new paths were taken which differed significantly from the previous substructures and which should serve as a model for the further pyramid construction. For the first time, a part of the chamber was moved up into the pyramid body. The underground parts were no longer carved out of the rock, but were lined up in a long, open pit, which was to become the most frequently used technique for the construction of the substructure.

The entrance to the pyramid is on the north side at a height of approx. 18.5 m. From here a 1.55 m high and 0.85 m wide corridor leads down. Shortly before the end of the descending passage there is a small, vertical shaft, which was presumably intended to drain water in order to prevent the underground parts from flooding in the event of rain during construction. The passage opens directly into the first passage chamber, which is a niche-like extension of the passage to the left, but has the same height of 1.75 m. Their dimensions are 2.60 m × 2.20 m. From there you get directly to the second passage chamber, which is about the same size as the first (2.65 m × 2.10 m), but is located on the right side of the passage. Both passage chambers have a flat ceiling, the stone slabs of which extend over the entire width and have no cracks.

The two passage chambers may have contained locking stones that were moved from the niches into the passage when the pyramid was sealed. Stadelmann also sees this as the first realization of the three-chamber scheme, which extends with variations through the pyramids of the 4th dynasty.

After the second passage chamber, a 4.55 m long passage leads to a vertical shaft that leads up to the actual main chamber. The burial chamber has the dimensions 5.90 m × 2.65 m and a height of 5.05 m and, as in previous buildings, is oriented in a north-south direction. The upper end is formed by a cantilever vault that dissipates the pressure of the masonry on the side of the chamber. There is no stone sarcophagus in the burial chamber, and no debris has been found. Since the sarcophagus could not be brought into the chamber through the vertical shaft, it can be concluded that the chamber never contained one. In the vault of the chamber as well as in the vertical shaft there are wooden beams, which were probably originally intended to be used to bring in the wooden coffin.

In the corridor and chamber system there are no storage rooms or magazine galleries, which were present in large numbers in the substructure or in the complex of the pyramids of the 3rd Dynasty.

In 1999, Gilles Dormion and Jean-Yves Verd'hurt discovered pressure relief chambers and ducts located above the two duct chambers, the lower part of the sloping duct and above the connecting duct between the duct chambers and the vertical access shaft. Only the short corridor from the north wall of the vertical shaft has been opened. All other pressure relief chambers have so far only been examined endoscopically . These chambers all consist of cantilever vaults, which divert the pressure of the pyramidal mass on them onto the masonry on the side of the chambers, so that the underlying flat ceiling stones are relieved and thus breaks are avoided.

With these chambers, a pressure relief was carried out for the first time in the pyramid construction, which was not necessary in the previous buildings, as the corridors and chambers were carved into the massive rock bedrock or their ceiling beams were extremely massive.

Pyramidal complex

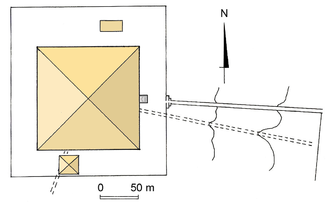

The pyramid complex was surrounded by a 2 m high enclosure wall, which had an extension of 236 m in a north-south direction and 218 m in an east-west direction, of which only very few remains have been preserved. It enclosed several elements that were to be characteristic for the later pyramid construction and a pyramid complex. The enclosed pyramid courtyard had a floor made of dried clay.

Pyramid temple

The original mortuary temple, which was built at the end of the second phase (E2), no longer exists, as it had to make way for the third construction phase (E3). This original temple was probably also on the east side, because the high entrance to the pyramid meant that the previous space on the north side was no longer available. In its place, since the pyramid was no longer intended as a grave at the time of the third construction phase, instead of an extensive mortuary temple, only a small, chapel-like pyramid temple was built. For the first time, this is not on the north side, but on the east side, where the mortuary temple was also located in later pyramids.

The temple has a very simple structure and consists of only two rooms that lead to a small open courtyard by the pyramid, in which there is an altar and two large, unlabeled steles . The width is 9 m and the length 9.18 m. The original ceiling panels of the roofed part of the temple are still in place undamaged. Therefore it is considered to be the best preserved temple in the Old Kingdom.

Temple magazines and false doors , which were always present in the larger mortuary temples, are completely missing here.

The good degree of preservation is due to the fact that the temple was hidden under the rubble belt of the pyramid for a long time and thus protected from stone robbery.

Cult pyramid

On the south side there was a small secondary pyramid, the heavily damaged remains of which were found by Petrie. It is the oldest example of a cult pyramid that functionally replaced the south grave of the earlier step pyramids.

The entire superstructure and part of the substructure have been largely destroyed. Vito Maragioglio and Celeste Rinaldi reconstructed from the remaining parts that it was probably a step pyramid with a base length of 26.3 m and three or four steps. As in the main pyramid, the masonry was arranged in inwardly sloping layers.

The substructure was similar to that of the main pyramid and consisted of a sloping corridor that led from the north to the main chamber. Excavations in the area of the cult pyramid brought to light a fragment of a limestone stele on which Horus was depicted.

The finds so far did not provide any evidence that the secondary pyramid was also converted into a real pyramid.

Queen's tomb

On the north side of the pyramid courtyard are the remains of a mastaba grave , which was probably planned for one of the royal wives. During excavations, a woman's skeleton was found, but no artifacts that could be used to assign the tomb to a specific queen.

On the way

An element that appeared for the first time in this pyramid complex and became a standard component in practically all other pyramid complexes was the pyramidal path. Here it was cut into the rock underground, paved with clay and provided with limestone walls on the sides. No signs of roofing were found. The pathway was only excavated in the immediate vicinity of the pyramid and not followed to its end on the valley side.

Petrie discovered another canal-like incision south of the driveway, which led directly to the center of the pyramid from an east-southeast direction. Also cut into the rock, it had adobe walls . This may be an abandoned previous version of the Aufweg.

Valley temple

The valley temple is always located in the extension of the access path in later pyramids. Here, however, only a few remains of mud brick wall were found during excavations. This could be a preliminary stage of the valley temple, but it is also conceivable that, in view of the rudimentary execution of the other elements of the complex, only a very simple structure was built here as the pyramid no longer had a funerary function. The remains of the wall could also have belonged to the pyramid city of Sneferu.

The Meidum necropolis

The Mastaba M17 , which Petrie explored in 1917, is located directly on the east side of the pyramid's perimeter wall . It is made of unfired adobe bricks and its builder is unknown. The sarcophagus found inside had no inscriptions and housed a feathered mummy. M17 was filled with limestone rubble from the construction of the pyramid - probably the third construction phase.

About 600 meters north of the pyramids is the great necropolis of the princes and dignitaries of the 4th Dynasty under King Sneferu. Very beautiful ornate graves have been found here. In 1817 Auguste Mariette uncovered the famous M16 Mastaba Chapel . It belongs to the prince and presumably master builder of the Meidum pyramid Nefermaat and contains the famous "Goose Frieze of Meidum".

The two well-known seated figures of Rahotep and his wife Nofret, which are now in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo , come from the nearby Mastaba M15 of Prince Rahotep .

Significance for the further pyramid development

With the Meidum pyramid, new techniques were introduced especially for the construction of the substructure, even if the pyramid construction itself still remained attached to the 3rd dynasty. Numerous other elements such as the cult pyramid, the position of the pyramid temple and the pyramid complex formed the prototypes for all subsequent pyramids of the Old Kingdom. With the reconstruction of phase E3, the pyramid was then externally adapted to the state of the pyramid construction of the 4th dynasty.

literature

General overview

- Mark Lehner : The first wonder of the world. The secrets of the Egyptian pyramids. Econ, Düsseldorf / Munich 1997, ISBN 3-430-15963-6 .

- Frank Müller-Römer : The construction of the pyramids in ancient Egypt. Utz, Munich 2011, ISBN 978-3-8316-4069-0 , pp. 93ff.

- Miroslav Verner : The pyramids (= rororo non-fiction book. Volume 60890). Rowohlt, Reinbek bei Hamburg 1999, ISBN 3-499-60890-1 , pp. 185-195.

- Peter Jánosi : The pyramids. Myth and Archeology. Beck, Munich 2004, ISBN 3-406-50831-6 .

- Alberto Siliotti, Zahi A Hawass: Pyramids. Pharaohs tombs of the Old and Middle Kingdom. Müller, Erlangen 1998, ISBN 3-86070-650-0 .

Questions of detail

- Ludwig Borchardt , Louis Croon: The origin of the pyramid demonstrated by the construction history of the pyramid at Mejdum. With a contribution about load transport and construction time / by Louis Croon (= contributions to Egyptian building research and antiquity. Vol. 1,2). Springer, Berlin 1928.

- Gilles Dormion, Jean-Yves Verd'hurt: The pyramid of Meidum, architectural study of the inner arrangement (= World Congress of Egyptology, Cairo, 28th of March-3rd of April 2000. ) ( PDF file; 1.06 MB ) .

- Carl Richard Lepsius : Monuments from Egypt and Ethiopia . Volumes of text. Volume II: Middle Egypt with the Fayum, 1849, Meidum, p. 1-6 ( online [accessed October 23, 2014]).

- William Flinders Petrie , F. Ll. Griffith et al .: Medum. D. Nutt, London 1892.

- Rainer Stadelmann : Sneferu and the pyramids of Meidum and Dahschur. In: Communications from the German Archaeological Institute, Cairo Department. (MDAIK) No. 36, ISSN 0342-1279 , von Zabern, Mainz 1980, pp. 437-449.

Web links

- Alan Winston: The Meidum (Maidam) Pyramid (Probably of Snefru) in Egypt

- The Meidum pyramid (English)

- The Pyramid at Meidum (pictures of the pyramid)

- The Pyramid at Meidum (pictures of the pyramid interior)

Individual evidence

- ^ Roman Gundacker: On the structure of the pyramid names of the 4th dynasty. In: Sokar, No. 18, 2009, pp. 26-30.

- ↑ a b Miroslav Verner: The pyramids. Reinbek 1999, p. 185 The pyramid of Snefru in Meidum

- ↑ Miroslav Verner: The pyramids. Reinbek 1999, pp. 185–186 The pyramid of Snefru in Meidum

- ↑ Ludwig Borchardt: The emergence of the pyramid, demonstrated by the building history of the pyramid at Mejdum. 1928.

- ↑ Miroslav Verner: The pyramids. Reinbek 1999, pp. 186–187 The pyramid of Snefru in Meidum

- ^ A b c Alan Winston: The Meidum (Maidam) Pyramid (Probably of Snefru) in Egypt

- ↑ Miroslav Verner: The pyramids. Reinbek 1999, p. 187 The pyramid of Sneferu in Meidum

- ^ A b Gilles Dormion, Jean-Yves Verd'hurt: The pyramid of Meidum, architectural study of the inner arrangement . (PDF file; 1.06 MB), 2000.

- ↑ Kurt Mendelssohn: The riddle of the pyramids . Bechtermünz, Augsburg 1996, ISBN 3-86047-216-X .

- ↑ a b Digital Egypt for Universities: A graffito found at the temple of the Meydum pyramid

- ↑ a b Mark Lehner: The first wonder of the world - The secrets of the Egyptian pyramids. Pp. 97-99.

- ↑ a b c Miroslav Verner: The pyramids. Reinbek 1999, p. 189 The pyramid of Snefru in Meidum

- ↑ Alberto Siliotti, Zahi A Hawass: Pyramids. Pharaohs tombs of the Old and Middle Kingdom. Erlangen 1998, p. 156.

- ↑ a b c d e Mark Lehner: Secret of the pyramids. P. 97 ff The first real pyramids: Meidum and Dahshur

- ↑ a b c Miroslav Verner: The pyramids. Reinbek 1999, pp. 192-293 The pyramid of Sneferu in Meidum

- ↑ Miroslav Verner: The pyramids. Reinbek 1999, p. 194 The pyramid of Sneferu in Meidum

- ↑ a b c d Rainer Stadelmann: The Egyptian pyramids. From brick construction to the wonder of the world. P. 80 ff.

- ↑ Alberto Siliotti, Zahi A Hawass: Pyramids. Pharaohs tombs of the Old and Middle Kingdom. Erlangen 1998, p. 145.

- ^ Günther A. Wagner: Introduction to Archaeometry. Springer, Berlin 2007, ISBN 978-3-540-71936-6 , p. 175.

- ^ A b Alberto Siliotti, Zahi A Hawass: Pyramids. Pharaohs tombs of the Old and Middle Kingdom. Erlangen 1998, p. 155.

- ↑ Peter Jánosi: The pyramids. P. 64.

- ↑ Miroslav Verner: The pyramids. Reinbek 1999, p. 191 The pyramid of Sneferu in Meidum

- ↑ Miroslav Verner: The pyramids. Reinbek 1999, p. 192 The pyramid of Snefru in Meidum

- ↑ Miroslav Verner: The pyramids. Reinbek 1999, pp. 189–190 The pyramid of Snefru in Meidum

- ↑ Alberto Siliotti, Zahi A Hawass: Pyramids. Pharaohs tombs of the Old and Middle Kingdom. Erlangen 1998, p. 154.

- ↑ a b c d e Miroslav Verner: The pyramids. Reinbek 1999, p. 193 The pyramid of Snefru in Meidum

- ↑ Vito Maragioglio, Celeste Rinaldi: L'Architettura delle Piramidi Menfite. Tip. Artale, Torino 1963-1977.

- ↑ a b Miroslav Verner: The pyramids. Reinbek 1999, pp. 185–195 The pyramid of Snefru in Meidum

| before | Tallest building in the world | after that |

| Djoser pyramid | (93 m) around 2600 BC Chr. |

Bent pyramid of Sneferu |

Coordinates: 29 ° 23 ′ 19 ″ N , 31 ° 9 ′ 26 ″ E