Missouri River High Bridge

Coordinates: 46 ° 49 ′ 5 " N , 100 ° 49 ′ 37" W.

| Missouri River High Bridge | ||

|---|---|---|

| Freight train the BNSF from the Powder River Basin crosses the bridge in 2009 ( superstructure of 1905, pillars of 1882) | ||

| use | Railway bridge | |

| Crossing of | Missouri River | |

| place | Bismarck and Mandan , North Dakota | |

| Entertained by | BNSF Railway | |

| construction | Truss bridge | |

| overall length | 465 m | |

| width | 6.7 m | |

| Longest span | 122 m | |

| Clear height | 21 m | |

| opening | 1882, 1905 | |

| planner |

George S. Morison (1882) Ralph Modjeski (1905) |

|

| location | ||

|

|

||

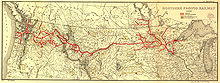

The Missouri River High Bridge , also called Bismarck Bridge , is a single-track railroad bridge over the Missouri between Bismarck and Mandan in North Dakota . The truss bridge of the BNSF Railway dates back to one of the first permanent railroad bridges over the Missouri from 1882, which was then built as part of the northern transcontinental railroad connection of the Northern Pacific Railway from Puget Sound in Washington to Duluth on Lake Superior . Due to the rapid development of locomotives and freight volumes, it had to be rebuilt in 1905 and is still used today by the BNSF, in which the Northern Pacific has been merged, for rail freight transport, including transporting coal from the Powder River Basin in Wyoming and Montana .

history

After the completion of the first transcontinental railroad from Sacramento to Omaha in 1869 by the Central Pacific Railroad (CP) and Union Pacific Railroad (UP), the Northern Pacific Railway (NP) began in 1871 with a northern transcontinental railroad from Puget Sound in Washington through the states Idaho , Montana , North Dakota and Minnesota to Duluth on Lake Superior . In 1872 the UP realized its permanent connection to the railway network to the east coast of the USA through the Omaha Bridge over the Missouri , the NP wanted to cross the river at Bismarck in North Dakota. Due to the economic crisis of 1873 , the Northern Pacific got into trouble and had to file for bankruptcy in 1875. The construction work came to a standstill in front of Bismarck in 1873 and could only be continued six years later after a reorganization of the NP.

First bridge 1882

In Bismarck, the Missouri was crossed laboriously by rail ferries and, in winter, by temporary railroad tracks across the frozen river. In early 1880, the bridge construction engineer George S. Morison was hired to build a bridge . He analyzed the river bed by means of test drillings and favored a location near the sidings with the lowest possible depth of bedrock. In the then extensive river bed, the main stream of the Missouri often changed its position after the spring floods due to sand deposits and the location chosen by Morison for the bridge was almost one kilometer wide. In order to keep the river at low tide in the long term under a bridge with a manageable length, had Morison upriver on the west bank an extensive dike design that limited the river about 300 meters, was but submerged at high tide to the location on the west bank settlement Mandan not to endanger; At the same time, long-term sand deposition behind the dike was sought. The hydraulic engineering measures began at the end of 1880 and in May 1881 the construction of the bridge piers could begin. The masonry stone pillars were built in the river bed using large caissons , which were 8 meters wide and 23 meters long and lowered to the bedrock. The iron trusses of the bridge could be completed a year later and already had the first parts of the new building material steel . The first test train ran in October 1882, the completion of the northern transcontinental railroad connection was completed in September of the following year with the hammering of the golden nail in Montana by the US President Ulysses S. Grant .

New superstructure in 1905

Although Morison tried when dimensioning the bridge to take into account the future load from stronger locomotives and increasing transport loads, the construction came to its load limit after the turn of the millennium. The NP felt compelled to act and hired Ralph Modjeski, a former student of Morison, who was involved in several Morison bridges between 1885 and 1892 and then opened his own engineering office, which continues to this day as Modjeski & Masters . Modjeski constructed a new superstructure with a 2.5 times higher load-bearing capacity, but the Northern Pacific was unable to interrupt its important main connection over the bridge during the eight-month renovation phase. It was therefore decided to replace the superstructure with their own personnel under the direction of Modjeski, which was completed by the end of December 1905. For this purpose, massive wooden scaffolding was installed under the lattice girders, which could carry both the steel structures and the load of the passing trains.

Since the completion of the first Bismarck Bridge in 1882, there have been earth movements on the Bismarck side; the hill forming the east bank moved slowly but steadily towards the river. This led to a displacement of the first bridge pillar of up to nine centimeters annually. In the following years, Morrison had to have countermeasures carried out several times, which resulted in the pillar being exposed in 1898, which was then pushed back on a stronger foundation at its original location. Unfortunately, the movement of the east bank continued and only a massive removal of the hill in the 1950s was it possible to reduce the movement of the pillar to about one centimeter per year.

description

Today's bridge with a total length of 465 m consists of three central 122 m long truss girders with a track below, followed by a shorter truss girder each with a track above to the respective abutment (west bank 35.1 m, east bank 43.4 m). Modjeskis new superstructure with a designed load capacity of two 188 ton locomotives, followed by about 7 tons of loads per meter track, is unlike Morison iron Whipple -Fachwerken (whipple truss) with straight top chord, from special Pratt trusses (Pennsylvania truss) from Steel with a curved upper chord, which was more material-saving in design when higher loads were required than the Whipple trusses, which were then increasingly outdated. Since the bridge piers from 1882 were used for the second superstructure in 1905, the length of the central girders did not change, only the girder to the east bank was lengthened due to the movement of the earth moving the first pillar. The massive stone-walled pillars have been preserved in their original form and the river pillars also have an inclined edge protection reinforced with iron in the upstream direction, which breaks up the ice floes carried by the river and protects the pillar when the ice drifts.

Web links

- Missouri River High Bridge. John A. Weeks III.

- BNSF - Missouri River High Bridge. Bridgehunter.

- Bismarck Bridge, Spanning Missouri River, Bismarck, Burleigh County, ND. Historic American Engineering Record, HAER ND-2.

literature

- Clayton B. Fraser: Nebraska City Bridge. Historic American Engineering Record, HAER No. NE-2, Denver, Colorado 1986, pp. 69-98.

- Edward C. Murphy: The Northern Pacific Railway Bridge at Bismarck. State Historical Society of North Dakota 2017.

- New Bismarck Bridge of the Northern Pacific. In: Railway Age. Vol. 40, No. 8, 1906, pp. 174 f.

Individual evidence

- ^ Edward C. Murphy: The Northern Pacific Railway Bridge at Bismarck. State Historical Society of North Dakota 2017, p. 2 f.

- ^ Edward C. Murphy: The Northern Pacific Railway Bridge at Bismarck. State Historical Society of North Dakota 2017, pp. 6-10.

- ^ A b Clayton B. Fraser: Nebraska City Bridge. Historic American Engineering Record, HAER No. NE-2, Denver, Colorado 1986, pp. 69-98.

- ^ A b New Bismarck Bridge of the Northern Pacific. In: Railway Age. Vol. 40, No. 8, 1906, pp. 174 f.

- ^ Edward C. Murphy: The Northern Pacific Railway Bridge at Bismarck. State Historical Society of North Dakota 2017, pp. 15-19.

- ^ Glenn A. Knoblock: Historic Iron and Steel Bridges in Maine, New Hampshire and Vermont. McFarland, Jefferson 2012, pp. 33-37.