George S. Morison

George Shattuck Morison (born December 19, 1842 in New Bedford , Massachusetts , † July 1, 1903 in New York City ) was an American lawyer , railroad manager and civil engineer . After studying law and briefly as a lawyer, Morrison set out for a career as a civil engineer. Without formal training in the field, he gained his first experience under Octave Chanute and pursued intensive self-study, which he maintained throughout his professional career. Morison devoted himself primarily to bridge building at the time of the expanding railroad companies in North America at the end of the 19th century and became one of the leading experts in this field. He has produced over twenty large railway bridges , among others, on the Missouri , Mississippi and Ohio , including the three-kilometer Cairo Rail Bridge (1890) the then longest steel - truss bridge in the world and with the Frisco Bridge (1892), the cantilever bridge with the then longest wingspan in North America. In addition, Morison was President of the American Society of Civil Engineers in 1895 and a member of the Isthmian Canal Commission from 1899, which worked out a route for a shipping canal in Central America and decided on the initiative of Morison for the later Panama Canal .

Adolescent years and law studies

George Shattuck Morison was the eldest of three siblings and was born in New Bedford , Massachusetts in December 1842 to John Hopkins and Emily Rogers Morison. His parents were descendants of Scottish-Irish and English immigrants and came from well-off families in New England . When Morison was three years old, the family moved to Milton , near Boston , where his father was pastor of the Unitarian Church , a position he held until 1880. After finishing school, George S. Morison attended Phillips Exeter Academy from 1856, like his father, and Harvard College from 1859 . In addition to Latin , ancient Greek , rhetoric and history, his studies in the fine arts also included natural sciences and mathematics, for which he showed a special talent. He was considered an inconspicuous student without special preferences, was a member of the Phi Beta Kappa and obtained his Bachelor of Arts degree in 1863 as the ninth-best of 121 students. A year later he went to Harvard Law School , where he graduated with a Bachelor of Laws in 1866 . He was then accepted into the New York State Bar Association and was employed by the renowned law firm Evarts , Southmayd and Choate . A little later, he began to have doubts about his career choice. Neither the prospect of a successful legal career nor a university career in the field of law seemed worthwhile goals for Morison. For him, there was a lack of precision and determination in legal activities, qualities that he valued in contrast to mathematics and the laws of nature. Disillusioned and unhappy he decided finally civil engineer and to be left in August 1867 - at the age of 23 years - the law firm in New York, to a time of economic upheaval, two years after the end of the American Civil War , on the development of the West of the USA to participate. He wrote in his diary:

Last day at the office as in the law ... so ends my legal life in which I have blundered along for these three years; may these years not prove wholly wasted. May I now in my new profession for which I have no doubt that I am much better fitted, work with a degree of interest and power which will make my life valuable both to myself and to others.

“The last day in the law firm and also as a lawyer… so ends my legal career through which I have struggled through the last three years; may these years not turn out to be entirely wasted. May I work in my new profession, for which I am undoubtedly better suited, with a degree of interest and strength that can give my life value for myself and others. "

Civil engineer and bridge construction

Beginnings

The Civil Engineering stuck at that time in the US is still in its infancy. Training in this area mainly related to canal and hydraulic engineering for the most important transport routes at the time, but these were increasingly being replaced by the railroad. You learned your trade primarily on site under construction projects under experienced engineers. So Morison turned to the advice of friends to the railroad magnate James Frederick Joy from Detroit , who wanted to expand the network of his railroad companies to Missouri , Kansas and Nebraska . Joy sent Morison to Octave Chanute in 1867 , who was in charge of building the first railroad bridge over the Missouri in Kansas City . Chanute initially tried to talk Morison out of the desired career due to his lack of specific training and introduced him to the rough everyday life on a large construction site. Convinced of his choice and equipped with a solid mathematical education, Morison acquired the necessary theoretical knowledge in self-study and learned the technical skills of a civil engineer while building the Kansas City Bridge for the Hannibal and St. Joseph Railroad . He became an assistant engineer until it was completed in the summer of 1869 and the following year he published a detailed treatise with Chanute on the construction of the bridge, one of the first project reports and prototypes for the following in civil engineering. Morison stayed in Kansas City until 1871, continued to work under Chanute on the expansion of Joy's railroad lines and then became chief engineer on a smaller route from Michigan to Indiana and, from 1873, liaison engineer for the Eastern Division of the Erie Railroad in New York.

In 1875, Morison designed his first own bridge for the Erie Railroad , the new construction of the Portageville Viaduct , which was destroyed by fire in May of that year. According to Morison's plans, the iron Trestle Bridge could be completed by the end of June 1875, just 86 days after the fire. It is still used today as an example of iron bridge constructions in America at the time and was the beginning of Morison's career as one of the leading bridge construction engineers of his time. However, five years passed before his next bridge construction project, as he left the Erie Railroad at the end of 1875 and in the following years worked as a railroad manager and consulting engineer for the American agency of the Baring Brothers and Company and with the civil engineer George S. Field until 1880 ran a construction company in Buffalo .

Missouri River Bridges

In early 1879 Charles Elliott Perkins , president of the Chicago, Burlington and Quincy Railroad (CB&Q), hired Morison to build a railroad bridge over the Missouri near Plattsmouth , Nebraska . Morison designed a high truss bridge made of wrought iron with two central Whipple - trusses (Wipple truss) with bottom-track. In contrast to all previous bridges over the Missouri, he decided against a movable bridge part and was able to convince Perkins of the advantages of high bridges, which, due to the predominantly high embankment on the Missouri, are more cost-effective to build and also to maintain than rotating , folding or lift bridges . The construction work began in August and could be completed a year later , despite the laborious erection of the river pillars using caissons . Morison worked here for the first time as an assistant with the civil engineer Charles Conrad Schneider , who originally came from Apolda in Thuringia , Morison assisted on other bridges until 1883 and later designed the Washington Bridge (1889) in New York, among other things .

Morison's reputation rose with the construction of Plattsmouth Bridge ; In the following years he received numerous orders from several railroad companies to cross the Missouri. By 1888 he built six more bridges over the river in Bismarck , Blair , Omaha , Rulo , Sioux City and Nebraska City , none of which have survived in their original design today, but the renovations or new constructions are still being made for the Rail freight traffic used. The Bismark Bridge was the first bridge over the Missouri in the Dakota Territory and part of the northern transcontinental railroad connection of the Northern Pacific Railway , completed in 1883 , from Puget Sound in Washington to Duluth on Lake Superior . The new Omaha Bridge was the successor to the Union Pacific Railroad , which, with the first bridge in 1872, connected the first transcontinental railroad from 1869, between Sacramento and Omaha, to the route network towards the east coast of the USA . In addition to the Rulo Rail Bridge, both bridges are still part of important sections of the BNSF Railway and Union Pacific for the transport of coal from the Powder River Basin in Wyoming and Montana , from whose opencast mines around 40 percent of the coal supply in the United States comes. Morison already experimented with the new building material steel for the Plattsmouth Bridge and increasingly replaced the proportion of wrought iron, which made it possible to reduce the dead weight of the bridge structures. He also standardized his designs and almost exclusively used Whipple trusses as central elements. During this time he worked alongside CC Schneider for the first time with Alfred Noble and Ralph Modjeski . In 1887 he also entered into a partnership with Elmer Lawrence Corthell and worked with him until 1889 as Morison & Corthell .

Bismarck Bridge

Bismarck , 1882Blair Crossing Bridge

Blair , 1883Omaha Bridge

Omaha , 1887

Morison built ten railroad bridges across the Missouri and made the transition from iron to steel as a building material with the Nebraska City Railroad Bridge . In addition to the above, he later built the Bellefontaine Bridge (1893) above St. Louis and the Leavenworth Terminal Bridge (1894) above Kansas City on the eastern and western borders of Missouri and, towards the end of his career, a new superstructure for the Atchison Swing Bridge (1901), one of the first bridges over the river from 1875, which is still in operation in Atchison , about 30 kilometers above Leavenworth .

| ||||||

Mississippi and Ohio River Bridges

If the construction of the Missouri River bridges was primarily driven by the expansion of the railroad companies in the western United States, the situation on the Mississippi and Ohio was different. At the end of the 19th century, the railway companies increasingly competed for steam navigation on the rivers; the previously practiced translation by train ferries became an obstacle to increasing transport capacities. For the shipping companies, the construction of bridges not only increased competition, but also hindered the high chimneys of the steamers, which led to state requirements regarding the height of the bridges or the regulation of movable bridge parts.

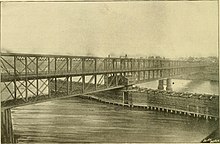

In late 1886, Morison was contacted by the Illinois Central Railroad and the Chicago, St. Louis and New Orleans Railroad , who were planning a bridge to connect their railroad networks at the confluence of the Mississippi and Ohio near Cairo , Illinois . Morison and Corthell examined the plans of the railroad companies in the spring of 1887 and visited the site of the planned Ohio crossing. Due to the required clear height of 16 meters during floods , the inefficiency of a swing bridge and the flat embankment as well as extensive flood plains , Morison and Corthell had to construct a bridge with elongated access roads. This made the Cairo Rail Bridge the longest steel bridge in the world when it was completed in 1890. Its 52 trusses added up to a total length of over three kilometers, which made it 10 meters longer than the Firth of Tay Bridge in Scotland from 1887. In addition, Morison exploited the maximum feasible span with Whipple trusses and integrated two 158-meter-long girders of his preferred type.

Morison later achieved an increase in the span with the Gerber girder patented by Heinrich Gottfried Gerber in 1866 , a special version of a cantilever bridge that he used for the first bridge ever built over the lower Mississippi . The Frisco Bridge in Memphis was built in collaboration with Alfred Noble , Ralph Modjeski and Walter E. Angier for the St. Louis - San Francisco Railway ( Frisco for short ) until 1892 . The 1.5 kilometer long truss bridge had the longest span (241 meters) of a cantilever bridge in North America and is considered to be Morison's most important structure. In the immediate vicinity are two more bridges based on Morison's design by Ralph Modjeski ( 1916 ) and Frank M. Masters ( 1949 ), who had worked on the previous structure under their teacher at the time. Morison built a total of five Mississippi River bridges in St. Louis , Winona , Memphis, Burlington and Alton , two of them again for Charles Elliott Perkins and his Chicago, Burlington and Quincy Railroad , which Morison hired for a total of six bridges during his career.

Frisco Bridge (center)

Memphis, Tennessee , 1892Alton Bridge (center)

Alton , 1894 (bridges and barrage were dismantled)

More bridges

In addition to the many Missouri and Mississippi River bridges, Morison also built some bridges in the Pacific Northwest . The Oregon Railway and Navigation Company , located there, operated steamboat and railroad lines in Washington and Oregon and in 1888 hired Morison to build two swing bridges over the Willamette in Portland and over the Snake in Whitman County , near the former settlement of Riparia . These were the first swing bridges designed by Morison himself, and in Portland the required simultaneous transfer of road and rail traffic posed a particular challenge. Together with Elmer Lawrence Corthell, he designed a double-decker bridge that ran a track within the 12-meter-high Whipple truss on the lower level and could be used by pedestrians and individual vehicles on an intermediate level above. At the same time, shipping traffic on the Willamette was not allowed to be hindered, which he realized in the design with a swiveling bridge section over 100 meters long. The steel bridge was the first of its kind in Portland and in the entire Pacific Northwest and was given the name Steel Bridge by the population . On the other hand, he kept the execution of the bridge over the Snake in a design that was common at the time, with two rigid Whipple trusses with a track below and a 100 meter long rotating segment with two symmetrical arms, the trusses tapering slightly towards the end due to their inclined upper chord . He later chose this design in modifications for other swing bridges in Jacksonville (1890), Winona (1891), Burlington (1893), Leavenworth (1894), Alton (1894) and Atchison (1901).

In the 1880s, Morison also had the opportunity to build on his first structure, the Portageville Viaduct , and built similar steel scaffolding pier viaducts with the Marent Gulch Trestle in Montana in 1885 and the Maroon Creek Bridge in Colorado in 1888 , which have survived to this day (2018) like the Boone Viaduct in Iowa , one of the longest and tallest double-track trestle bridges of the time, which Morison was involved in building around 1900 as a consulting engineer. Train traffic has been running over the neighboring Kate Shelley High Bridge since 2009 , but the old viaduct has still been preserved.

Portageville Viaduct

New York , 1875Marent Gulch Trestle

Montana , 1885Maroon Creek Bridge

Colorado , 1888Boone Viaduct

Iowa , 1901

Consulting activities and end of career

With the end of the strong expansion of the railroad in the second phase of the Great Depression from 1873-1896 , Morison's bridge building projects for the railroad companies ended and he increasingly turned to other projects. He was a member of the Phillips Exeter Academy Board of Trustees from 1888 and Chairman of the Board of Trustees from 1898, and he was committed to its expansion, including the design and construction of three student dormitories ( Soule Hall 1893, Peabody Hall 1896, Hoyt Hall 1903). He was also an active member of several engineering associations in the USA such as the Western Society of Engineers , the American Society of Mechanical Engineers and the American Society of Civil Engineers , of which he was president in 1895.

Towards the end of his career, Morison was mainly active as a consulting engineer on many government construction projects. Among other things, from 1894 onwards the New York and New Jersey Bridge Board to investigate a possible suspension bridge over the Hudson , which was only realized many years after his death with the George Washington Bridge in 1931. From 1895 he worked for the New York Dock Department in the expansion of the port facilities and from 1896 in a commission for the construction of the port of Los Angeles . In 1898, in collaboration with the architect Edward Pearce Casey, he won a tender to design an arch bridge over the Rock Creek Valley in Washington, DC , which was not completed until 1907. He also worked from 1900 for the State Engineer and Surveyor of New York on the expansion of the Erie Canal and from 1902 on a commission to investigate the later Manhattan Bridge (1910).

Under President William McKinley , he was appointed to the first Isthmian Canal Commission in 1899 to investigate a possible shipping canal in Central America , which in 1901, similar to previous commissions, favored a Nicaragua Canal . Morison then wrote a Minority Report and gave several lectures, in which he discussed the benefits of a Panama Canal . He initiated a broad discussion, which resulted in a lowering of the purchase price of the French company Compagnie Nouvelle du Canal de Panama and thus in 1902 to the purchase and later completion of the Panama Canal by the USA. David McCullough compared Morison's contribution in the sequence of events, inconspicuous at first sight, with a butler who appears at the end of the crime thriller, who was always present and inconspicuously holding the strings in his hand and around whom the whole plot revolved.

In addition to the numerous published project reports, Morison also wrote technical articles and gave lectures in which, among other things, he addressed the importance and position of engineering and universities and made further philosophical reflections on the future of mankind. Originally inspired by the work of his fellow students at Harvard and later philosophers Charles Sanders Peirce and John Fiske , especially by his book The Discovery of America , he developed his ideas further and compiled a summary of his lectures under the title The New Epoch as Developed by the Manufacture of Power , which was only published after his death in November 1903. Like his engineering colleague Robert Henry Thurston, he foresaw an era as a result of the machine age in which engineers would be able to generate unlimited amounts of energy. In the society that is developing from this, adequate education of all people worldwide will inevitably lead to the elimination of barbarism, ignorance and superstition. Morison saw in the engineer the model of this era and the “new priest” of technological development, and he was convinced of the unlimited possibilities for shaping living conditions in the future. After that, humanity will have a long period of rest, characterized by contentment, comfort and happiness. The technical historian David F. Noble reminded Morison's utopia of John Adolphus Etzler's The Paradise within the Reach of all Men . Sixty years later, Elting E. Morison , Morison's great-nephew and technology historian at MIT , saw unsustainable promises in Morison's utopia, since the possibilities of the steam engine and steel production, as well as all subsequent technological developments, gave man only limited power over the forces of nature, which is steadily increasing has, but could not displace nature as the still dominant factor.

Private life

Morison remained a bachelor his life and devoted himself primarily to his career. He viewed leisure activities as a wasteful distraction from his projects and only went on a private trip once. During his collaboration with Corthell, he set off from New York on a six-month trip around the world with his sister Mary in November 1887, visiting Europe and Egypt as well as India , China and Japan . Against the background of this long absence from his construction projects, which required a reliable supervisor, the partnership with Corthell should also be seen during this time, which was limited to two years from the start.

In the early 1890s, Morison began building his own house with an attached barn and windmill in Peterborough , New Hampshire , in the place of his childhood where he had spent the summer holidays with his father's brother. Due to his frequent absence, the house could not be completed until 1897, and after that he only spent about 50 days on the property. His sister Mary used it for another 14 years until her death, and his younger brother Robert then used it for another eight years. The solidarity with Peterborough is also expressed in his commitment to the local city library, for which he designed the new library building while he was building his house.

Morison, who had not been seriously ill since childhood, died unexpectedly early on July 1, 1903 in his apartment in New York after he was diagnosed with an inoperable abscess in May .

After-effects and reception

Building on the work of the pioneers of structural engineering in the USA, Stephen Harriman Long and Squire Whipple , Morison made decisive contributions to the further development of civil engineering. He introduced the detailed documentation of construction projects with specifications and progress reports and standardized the design and construction methods that made bridge construction more precise and efficient. In addition, he developed test methods and control measures to check the specifications, both in the manufacture of the structural elements and in the constructions built from them. He was in charge of the introduction of steel in bridge construction and contributed to the qualitative development of the steel industry by establishing reviews of the specifications on the manufacturer's side.

Morison's bridges are very similar in appearance and are characterized by a purely functional design. With the exception of the Taft Bridge designed towards the end of his career, aesthetic aspects were never in the foreground for him. He always viewed his buildings as tools that had to serve a very specific purpose. For him, the best bridge was the one that guides traffic most effectively and safely over the obstacle to be crossed at the lowest cost. This becomes clear in his 1890 in St. Louis for the St. Louis Merchants Exchange as an alternative to the Eads Bridge (1874) built Merchants Bridge . James Buchanan Eads ' Bridge is still a prominent landmark in the city and was included in the list of historic civil engineering milestones , while Morison's equally large Merchants Bridge was never considered particularly beautiful by the general public, but has been leading for over 120 years reliable rail freight traffic across the Mississippi. In his view, the simplest tool was always the best tool, and so he used proven construction elements, such as the Whipple truss, in a variety of bridge constructions, as long as it was the best available choice for the purpose. For the double-track Merchants Bridge , Morison used, for example, the truss with a curved top belt (Pennsylvania truss) developed by the Pennsylvania Railroad , which was more material-saving in design for higher loads than the increasingly outdated Whipple truss and was used until the 1930s.

Morison was not very popular with many of his employees because he was very direct and in places he lacked tact when dealing with colleagues. He showed open contempt for less talented people and was intolerant of faulty work, calculations or imprecise descriptions. Despite this character trait, which is often perceived as arrogant, many outstanding civil engineers worked under Morison during his more than 35-year career, to whom he, like his teacher Octave Chanute , passed on his knowledge and who, like him, continued to advance bridge building and civil engineering in the USA. In addition to Charles Conrad Schneider and Alfred Noble , who worked during Morison's lifetime, the young Ralph Modjeski deserves special mention, who was involved in various positions in several Morison building projects between 1885 and 1892 and later became one of the most important bridge construction engineers in the USA. Modjeski built over 40 bridges of almost all construction forms in many parts of the USA by 1936 and was the founder of the Modjeski & Masters engineering office, which still exists today .

Publications

- Octave Chanute, George S. Morison: The Kansas City Bridge: With an Account of the Regimen of the Missouri River, and a Description of Methods Used for Founding in That River. D. Van Nostrand, New York 1870 ( digitized ).

- George S. Morison, John Bogart, Edward P. North: American engineering as illustrated at the Paris Exposition of 1878. American Society of Civil Engineers, New York 1878 ( digitized ).

- George S. Morison: The Plattsmouth Bridge: A Report to Charles E. Perkins, President of the Chicago, Burlington, and Quincy Railroad. New York 1882 ( digitized ).

- George S. Morison: The Blair Crossing Bridge: A Report to Marvin Hughitt, President of the Missouri Valley and Blair Railway and Bridge Company. New York 1886 ( digitized ).

- George S. Morison: The New Omaha Bridge: A Report to Charles Francis Adams, President of the Union Pacific Railway Company. New York 1889 ( digitized ).

- George S. Morison: The Rulo Bridge: A Report to Charles E. Perkins, President of the Chicago, Burlington, and Quincy Railroad. Chicago 1890 ( digitized ).

- George S. Morison: The Sioux City Bridge: A Report to Marvin Hughitt, President of the Sioux City Bridge Company. Chicago 1891 ( digitized ).

- George S. Morison: The Nebraska City Bridge: A Report to Charles E. Perkins, President of the Chicago, Burlington, and Quincy Railroad. Chicago 1892 ( digitized ).

- Stuyvesant Fish, George S. Morison: The Cairo Bridge: Report of Stuyvesant Fish, President, to the Board of Directors of the Chicago, St. Louis, & New Orleans RR Co. February 24, 1892, report of George S. Morison, Chief Engineer, to the President of the Chicago, St. Louis & New Orleans RR Co., October 1, 1891. Knight, Leonard & Co., Chicago 1892 ( digitized ).

- George S. Morison: The Bellefontaine Bridge: A Report to Charles E. Perkins, President of the Chicago, Burlington, and Quincy Railroad. Chicago 1894 ( digitized ).

- George S. Morison: The Memphis Bridge: A Report to George H. Nettleton, President of the Kansas City and Memphis Railway and Bridge Company. John Wiley & Sons, New York 1894 ( digitized ).

- George S. Morison: Suspension Bridges - A Study. In: Transactions of the American Society of Civil Engineers. Volume 36, No. 793, 1896, pp. 359-416 ( digitized version ).

- George S. Morison: The New Epoch and the University. Oration Delivered Before the Phi Beta Kappa Society at Sanders Theater, Cambridge, Thursday June 25, 1896. Boston 1896 ( digitized ).

- George S. Morison: John Hopkins Morison, a Memoir. Houghton, Mifflin and Company, Boston and New York 1897 ( digitized ).

- George S. Morison: The Responsibilities of the Educated Engineer. Lafayette, Ind., University, 1901 ( digitized ).

- George S. Morison: The Isthmian Canal. An Address Before the Contemporary Club of Chicago, January 25, 1902 ( digitized ).

- George S. Morison: The Isthmian Canal. Delivered to Address April 24, 1902, Before the Massachusetts Reform Club. Reprint from the Railroad Gazette, May 9, 1902 ( digitized ).

- George S. Morison: The Isthmian Canal. A Lecture Before the Contemporary Club, Bridgeport, Conn., May 20, 1902 ( digitized ).

- George S. Morison: The New Epoch as Developed by the Manufacture of Power . Houghton, Mifflin and Company, Boston and New York 1903 ( digitized ).

literature

- Clayton B. Fraser: Nebraska City Bridge. Historic American Engineering Record, HAER No. NE-2, Denver, Colorado 1986 (contains the history, description, and specifications of several Morison bridges in over 500 pages).

- E. Gerber, HG Prout and CC Schneider: Memoir of George Shattuck Morison. In: Transactions of the American Society of Civil Engineers. Volume 54, 1905, pp. 513-521.

- Frank Griggs, Jr .: George S. Morison. Pontifex Maximus. In: STRUCTURE magazine. February 2008, pp. 54-57.

- WN Marianos, Jr .: George Shattuck Morison and the Development of Bridge Engineering. In: Journal of Bridge Engineering. Volume 13, No. 3, May 2008, pp. 291-298, doi : 10.1061 / (ASCE) 1084-0702 (2008) 13: 3 (291) .

Individual evidence

- ^ New England Historic Genealogical Society: The New England Historical and Genealogical Register. Volume 51, April 1897, p. 232.

- ^ E. Gerber, HG Prout and CC Schneider: Memoir of George Shattuck Morison. In: Transactions of the American Society of Civil Engineers. Volume 54, 1905, pp. 513-521, here p. 513 f.

- ^ Clayton B. Fraser: Nebraska City Bridge. Historic American Engineering Record, HAER No. NE-2, Denver, Colorado 1986, pp. 4-6.

- ↑ Quoted in Clayton B. Fraser: Nebraska City Bridge. Historic American Engineering Record, HAER No. NE-2, Denver, Colorado 1986, p. 4.

- ^ A b W. N. Marianos, Jr .: George Shattuck Morison and the Development of Bridge Engineering. In: Journal of Bridge Engineering. Volume 13, No. 3, May 2008, pp. 291-298, here p. 291 f.

- ^ Octave Chanute, George S. Morison: The Kansas City Bridge: With an Account of the Regimen of the Missouri River, and a Description of Methods Used for Founding in That River. D. Van Nostrand, New York 1870.

- ^ Clayton B. Fraser: Nebraska City Bridge. Historic American Engineering Record, HAER No. NE-2, Denver, Colorado 1986, pp. 7-21.

- ^ Clayton B. Fraser: Nebraska City Bridge. Historic American Engineering Record, HAER No. NE-2, Denver, Colorado 1986, pp. 21-28.

- ^ Clayton B. Fraser: Nebraska City Bridge. Historic American Engineering Record, HAER No. NE-2, Denver, Colorado 1986, pp. 37-68.

- ↑ George S. Morison: The Plattsmouth Bridge: A Report to Charles E. Perkins, President of the Chicago, Burlington, and Quincy Railroad. New York 1882, pp. 3, 10-18, 23 and 37.

- ^ W. Watson, N. Paduano, T. Raghuveer, and S. Thapa: US Coal Supply and Demand: 2010 Year in Review. US Energy Information Administration, 2010, pp. 1-7.

- ^ Clayton B. Fraser: Nebraska City Bridge. Historic American Engineering Record, HAER No. NE-2, Denver, Colorado 1986, pp. 103, 122, 145, 206.

- ^ Clayton B. Fraser: Nebraska City Bridge. Historic American Engineering Record, HAER No. NE-2, Denver, Colorado 1986, pp. 233, 409.

- ^ Clayton B. Fraser: Nebraska City Bridge. Historic American Engineering Record, HAER No. NE-2, Denver, Colorado 1986, p. 408.

- ^ Atchison Swing Bridge. John Marvig Railroad Bridge Photography, accessed March 22, 2018.

- ^ Clayton B. Fraser: Nebraska City Bridge. Historic American Engineering Record, HAER No. NE-2, Denver, Colorado 1986, pp. 221-225.

- ^ Clayton B. Fraser: Nebraska City Bridge. Historic American Engineering Record, HAER No. NE-2, Denver, Colorado 1986, pp. 226-261.

- ^ Clayton B. Fraser: Nebraska City Bridge. Historic American Engineering Record, HAER No. NE-2, Denver, Colorado 1986, pp. 315-363.

- ^ Clayton B. Fraser: Nebraska City Bridge. Historic American Engineering Record, HAER No. NE-2, Denver, Colorado 1986, pp. 264-269.

- ^ Clayton B. Fraser: Nebraska City Bridge. Historic American Engineering Record, HAER No. NE-2, Denver, Colorado 1986, pp. 270-272.

- ^ Riparia Bridge, Snake River. In: Scientific American. Supplement. Volume 32, No. 833, 1891, pp. 13303 f.

- ^ Clayton B. Fraser, Carl Hallberg: Maroon Creek Bridge; Bridge No. 201A. HABS / HAER Record, US Department of the Interior, National Park Service, Washington, DC 1984.

- ^ Robert W. Jackson: Chicago & Northwestern Railroad Viaduct. Historic American Engineering Record, HAER No. IA-44, Washington, DC 1995.

- ^ Oscar Fay Adams: Some famous American schools. D. Estes & Company, Boston 1903, p. 111 (digitized version) .

- ^ Clayton B. Fraser: Nebraska City Bridge. Historic American Engineering Record, HAER No. NE-2, Denver, Colorado 1986, pp. 401 f.

- ^ A b George S. Morison: Suspension Bridges - A Study. In: Transactions of the American Society of Civil Engineers. Volume 36, No. 793, 1896, pp. 359-416.

- ^ Robert Harvey et al: Connecticut Avenue Bridge (William H. Taft Bridge). Historic American Engineering Record, HAER No. DC-6, Washington, DC 1992.

- ^ Clayton B. Fraser: Nebraska City Bridge. Historic American Engineering Record, HAER No. NE-2, Denver, Colorado 1986, pp. 403-405, et al. 408 f.

- ^ Clayton B. Fraser: Nebraska City Bridge. Historic American Engineering Record, HAER No. NE-2, Denver, Colorado 1986, pp. 405-408.

- ^ David McCullough: The Path Between the Seas: The Creation of the Panama Canal, 1870-1914. Simon & Schuster, New York 1977, ISBN 978-0-671-24409-5 , pp. 324-328.

- ^ Charles Sanders Peirce: Reasoning and the Logic of Things: The Cambridge Conferences Lectures of 1898. Harvard University Press, 1992, ISBN 0-674-74967-7 , p. 33.

- ^ George S. Morison: The New Epoch as Developed by the Manufacture of Power . Houghton, Mifflin and Company, Boston and New York 1903 (digitized) .

- ^ David F. Noble: The Religion of Technology: The Divinity of Man and the Spirit of Invention. Penguin Books, 1999, ISBN 0-14-027916-4 , pp. 95 f .; Howard P. Segal: Technological Utopianism in American Culture. 20th Anniversary Edition, Syracuse University Press, New York 2005 (first Chicago 1985), ISBN 0-8156-3061-1 , pp. 30 f. and 53.

- ^ Elting E. Morison, Leo Marx, Rosalind Williams: Men, Machines, and Modern Times. MIT Press, Cambridge 1966, 50th Anniversary Edition 2016, ISBN 978-0-262-52931-0 , pp. 17-20.

- ^ Clayton B. Fraser: Nebraska City Bridge. Historic American Engineering Record, HAER No. NE-2, Denver, Colorado 1986, p. 402 et al. 233 f.

- ^ House tour on tap in Peterborough. SentinelSource, September 10, 2011, accessed March 3, 2018.

- ^ Clayton B. Fraser: Nebraska City Bridge. Historic American Engineering Record, HAER No. NE-2, Denver, Colorado 1986, p. 402 et al. 4 f.

- ↑ Elting E. Morison: The Master Builder: He was a no-nonsense engineer of bridges in a heroic age. In: Invention & Technology Magazine. Volume 2, No. 2, 1986, pp. 34-40 (available on the Internet Archive ).

- ^ History. The Peterborough Town Library, accessed March 3, 2018.

- ^ Clayton B. Fraser: Nebraska City Bridge. Historic American Engineering Record, HAER No. NE-2, Denver, Colorado 1986, pp. 413 f.

- ^ A b W. N. Marianos, Jr .: George Shattuck Morison and the Development of Bridge Engineering. In: Journal of Bridge Engineering. Volume 13, No. 3, May 2008, pp. 291-298, here pp. 295 f.

- ^ Clayton B. Fraser: Nebraska City Bridge. Historic American Engineering Record, HAER No. NE-2, Denver, Colorado 1986, pp. 41 f., 309 and 414.

- ^ WN Marianos, Jr .: George Shattuck Morison and the Development of Bridge Engineering. In: Journal of Bridge Engineering. Volume 13, No. 3, May 2008, pp. 291-298, here p. 296 f.

- ^ Clayton B. Fraser: Nebraska City Bridge. Historic American Engineering Record, HAER No. NE-2, Denver, Colorado 1986, pp. 279 f.

- ^ Glenn A. Knoblock: Historic Iron and Steel Bridges in Maine, New Hampshire and Vermont. McFarland, Jefferson 2012, ISBN 978-0-7864-4843-2 , pp. 33-37.

- ^ WN Marianos, Jr .: George Shattuck Morison and the Development of Bridge Engineering. In: Journal of Bridge Engineering. Volume 13, No. 3, May 2008, pp. 291-298, here p. 297.

- ^ Clayton B. Fraser: Nebraska City Bridge. Historic American Engineering Record, HAER No. NE-2, Denver, Colorado 1986, p. 8.

- ^ WF Durand: Biographical Memoir of Ralph Modjeski 1861-1940. National Academy of Sciences, Biographical Memoirs Volume 23, 1944, pp. 241-261.

- ↑ Legacy. Modjeski and Masters, accessed March 7, 2018.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Morison, George S. |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Morison, George Shattuck (full name) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | American lawyer, railroad manager, and civil engineer |

| DATE OF BIRTH | December 19, 1842 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | New Bedford , Massachusetts |

| DATE OF DEATH | July 1, 1903 |

| Place of death | New York City |