Papacha

The papakha , plurality Papachi ( Russian and Ukrainian папаха = papakha ; Georgian ფაფახი pʰɑpʰɑxi = papachi - here the singular, the plural is Georgian papachni ; aserbaidschanisch papaq ; Adyghe паӏо = pa'o ; Turkmen Papaha ; Chechen холхазан куй = cholchasan Kui ) is a traditional and still widespread Caucasian headgear for men and boys, which is also traditional in some parts of Central Asia , the Middle East and among the Russian-Ukrainian Cossacks . It is also a well-known part of the male costume of the Turkmens , Karakalpaks , Crimean Tatars and Nogais in western parts of the Eurasian steppes. The origin of the name is likely to be in Turkic languages such as Azerbaijani and Turkmen, where papaha and papaq simply mean ' hat '.

In the Imperial Russian and Soviet armies, the papacha was used as winter headgear for ranks from colonel and was a representative part of the uniform in the armed forces . In the meantime no longer used in the Russian armed forces from 1994 , it was reintroduced in winter 2005.

In German it is sometimes imprecisely referred to as a Cossack hat or Caucasian hat .

In Russia, a shortened form of the papacha called Kubanka was historically worn.

Fabric, form and function

The papacha is sewn from the fur of the domestic sheep , more rarely the domestic goat of regional breeds. Depending on the breed, it can consist of skins with short hair wool (e.g. fat- tailed sheep ) or with long hair wool (e.g. Caucasian wool sheep , angora goat , more rarely cashmere goat ). The Persian , the fur of the karaku lamb, is considered a particularly noble material . Papachi are mainly black or white, more rarely gray-silvery or brown, depending on the sheep or lambskin colors. Other types of fur are very rarely used.

Usually a papacha is cylindrical , sometimes the upper edge is sewn together horizontally, flat, or frustoconical , with the top also made of fur. The lid is often made of other materials such as felt, cotton, etc. Hemispherical shapes, which are mostly sewn from long hair skins, are much rarer. Many long-haired papachi ( called mangal kui in Chechen ), however, also have a cylindrical basic shape.

The Papacha not only offers good protection from the cold in the cold mountain regions, it also protects against heat build-up in summer. However, the ears remain largely unprotected, and it is not very windproof. In the case of very cold or strong winds, a hooded cape ( bashlik ) made of leather or fur turned inwards was therefore placed over it in some regions of the Caucasus , the long ends of which can be worn like a scarf or tied around the papacha.

The papacha should not be confused with the fur hats of the surrounding large regions. In the northern forest areas, people, e.g. B. the Tatars or the residents of Tsarism Russia or Poland-Lithuania , traditionally larger or higher hats made of sable fur , mink fur and other wild animal fur , not sheep or goat fur. These are not called papacha , but have other names, in Russia for example boyar hat or the Hasidic Schtreimel . The karakul hat , which is often worn in a boat shape, especially in Pakistan and Afghanistan , is not a papacha either. It is defined by the type of fur, not by shape or tradition.

distribution

Today the papacha is a typical Caucasian and Cossack headgear and is part of the traditional men's costume of the peoples of the North Caucasus ( Circassians , Ossetians , Chechens , Avars, etc.), most regions of Georgia and Azerbaijan , including many inhabitants of the Lesser Caucasus . It is widespread as far as Eastern Anatolia , Iranian Azerbaijan and some other mountain regions of Anatolia and Iran . In the 19th century, under the Qajar dynasty , many members of the Persian upper class also wore papachi made of Persian fur. In the Ottoman Empire and the subsequent Turkey , papachi were particularly popular among reform-minded politicians and in parts of the population at the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th century. In Georgia, they are still commonly worn in north-eastern Georgian mountain regions ( Pschawi , Chewsureti , Mtiuleti , Tusheti ), while other headgear is traditionally in use in north-western regions ( Svaneti , Mingrelia , Abkhazia ). With the expansion of the Cossacks in the 16th – 19th In the 19th century, especially to southern Siberia and the Far East ( Primorye area on the Amur and Ussuri ), papachi spread to these regions.

Although some peoples, such as the Circassians, Georgians, Azerbaijanis, Turkmen (also called Telpek here next to "Papaha" ) and Cossacks perceive the Papacha as part of their national costume, Papachi are actually not tied to individual peoples or religious communities.

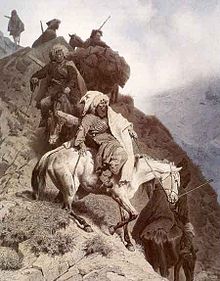

Typically North Caucasian, Georgian and Cossack is a combination of soft leather boots, papacha and Tschocha ( called " Tscherkeska " by the Cossacks ), a traditional felt coat that has been around small since the introduction of gunpowder (in this region around the beginning of the 17th century) Chest pockets for powder charges, later for cartridges was added. When it was cold, a second coat made of sheepskin was put on over it, the burqa , Georgian ნაბადი " nabadi ". The combination of soft boots, papacha, bashlik, chocha and burqa is very useful in very changeable weather conditions and also in frequent armed conflicts and therefore generally prevailed among Georgians, North Caucasians and Cossacks.

history

Fur hats as protection against the cold have a long tradition. Russian, Caucasian and Persian images from the Middle Ages up to the 16th to 18th centuries often show very tall fur hats suggesting wealth and other hat-like shapes made of inwardly turned fur with a brim , which became rarer in the 19th century. The historical high headgear of the Russian nobility, which was widespread up to the reforms of Peter the Great , is often referred to in German as a tubular hat or boyar hat . In Central Asia, Turkey and some Turkish-ruled Balkan countries they were called Kalpak . The name Kolpag for the Hungarian hussars can be traced back to Kalpak, the fur hat that was later introduced into other European armies . In the 18th and 19th centuries, the previously larger Kalpak of Turkey became increasingly similar to the Caucasian papacha. Even if kalpak originally referred to a high cap and papacha generally referred to a head covering, the two originally Turkish names were increasingly used synonymously in different languages. The name of the Central Asian people of the Karakalpak means 'Black Calpaks'. In Turkey the cap is called kalpak , only in Eastern Anatolia the name papacha is common. The name of the Eastern Anatolian Turkmen tribe, the Karapapaks, means 'black paper'.

The mystical current in Islam, Sufism ( dervishes ), is divided into many different schools , which can sometimes be recognized by the characteristic headgear. The Mevlevi Sufis are known in the west for their very high felt hats. The Eastern European Jewish mystics, the Hasidim, are also divided into different schools, which also wear different hats. In addition to the Schtreimel mentioned, some schools also have the higher Spodik , which is generally black and resembles the Papacha, others the likewise higher Kolpik , which is always brown-black and takes its name from the Central Asian Kalpak. As mentioned, like boyar hats, these are not made of sheep or goat skin, they are just similar to the papachi.

Papacha-like hats made of sheep and goat fur were also found in Southeastern Europe ( Balkans ); in contrast to the Caucasus and neighboring regions, they were mainly limited to cattle-breeding nomads and to shepherds who owned many sheep and goats. In Ottoman times, farmers, townspeople, aristocrats and civil servants wore sheep or goat fur hats less often (turban or fez and other hats). In contrast, the papacha was widespread in the Caucasus. This has social causes, in Southeastern Europe (as well as in Southern Europe ) full-time sheep and goat breeders formed their own profession. In parts of the Balkans they mostly belonged to the Romansh- speaking minority of the Wallachians . In contrast, the people in the high mountains of Europe and Asia were traditionally semi-nomads or lived in transhumance , i.e. the majority of the population of Caucasian mountain villages moved with the animals in winter on winter pastures in the lowlands until the ban on the tradition in Soviet times. So farmers and shepherds were not separate groups, but came from the same families. Fur hats were therefore more common in the Caucasus, while in the Balkans, Anatolia and Persia they were worn by shepherds and nomads, and less often by farmers or others. Only in the 19th and 20th centuries did the papacha first become part of the uniform of individual army units and high officers in the Russian army, then also in the Ottoman and Persian armies. It also became fashionable in civil life during this period and was often worn even by the upper classes up to the rulers.

In the course of their history the Cossacks only gradually adopted a style of clothing that is similar or similar to that of the Caucasians and some steppe nomads. The two earliest regional groups, the Zaporozhian Cossacks , who speak Ukrainian dialects, and the Russian dialect-speaking Don Cossacks , emerged from escaped serfs since the 14th century . They were always joined by individual steppe nomads and other neighbors. Although these Cossacks were often involved in mutual armed skirmishes , robberies and wars of retaliation with their neighbors, the Poles, Crimean Tatars, Ottomans, Nogayers and Circassians, there were changing coalitions and repeatedly neighboring tribes that joined the Cossacks (for example Tuhaj Bej ) and Cossacks who teamed up with their neighbors (for example the Pylyp Orlyk ). Later Cossack settlement areas ("Cossack armies") mostly arose from Don Cossacks, only the Kuban and Azov Cossacks from the Zaporozhian Cossacks. Many North Caucasians, often Ossetians, were involved in the formation of the Northeast Caucasian Terek Cossacks. As a result, the Cossack costume increasingly resembled the Caucasian and steppe nomadic.

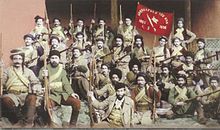

In the 19th century papacha and chocha (also bashlik and burqa) became the mandatory uniform of the Caucasian Cossacks. It was also worn by some regular mounted Cossack divisions within the Russian army; outside of the cavalry it was reserved for the highest generals only. During the Second World War, this uniform order was also reintroduced in the Soviet Army , but it no longer included so many Cossack units. This stimulated not only the papacha, but the entire uniform from Georgia and the North Caucasus from Papacha and Chocha, became popular with the Russian civilian population and beyond Russia's borders. The uniforms of the Persian Cossack Brigade and the Kurdish-Turkish paramilitary Hamidiye militia imitated the uniform of the Caucasian Cossacks, although the gasiren breast pockets for gunpowder charges had and only lost their military function in the second half of the 19th century due to the further development of firearm technology served as jewelry. In spite of their name, the Persian Cossacks were mostly not Russian-Ukrainian Cossacks, but locals who were based on the Cossack units of Russia.

During the 20th century, the papacha became rarer. In Turkey, state founder Ataturk banned it along with other traditional headgear through the Hat Act of 1925. The law is still in place today, but it is no longer enforced as strictly, but the papacha or kalpak are rarely seen in Turkey.

In Persia, officially Iran since 1935, it is still partly in use in more rural north-western mountain regions. For a long time Reza Schah Pahlavi , who was proclaimed a Shah in 1925 , also showed himself with the papacha, later he preferred a mixture of papacha, peaked cap and top hat , the Pahlavi cap ( Persian کلاه پهلوی/ kalāh pahlavi or kolāh pahlavi ). In 1928 an ordinance made it compulsory for all members of parliament, ministers and high officials. In addition, the following year it became compulsory headgear by law for all civil servants (except Shiite clergymen who still wore turban ) and all pupils and students at state schools and universities. Reza's son and successor, Mohammed Reza Shah , abolished the ordinance and the law; today nobody wears them there.

In the time of the Soviet Union , the papacha became rare among Cossacks. Because most of the Cossacks had fought on the side of the White Army against the Bolsheviks in the Russian Civil War , the Cossacks were stripped of the status of their own people in the Soviet era ; they were now regarded as Russians or Ukrainians. Some of them were banished, persecuted or evacuated, but Russians and Ukrainians were settled in the Cossack areas, their traditions were considered "counter-revolutionary". The persecution subsided with the Second World War, when a minority collaborated with the German Wehrmacht and the SS , while the majority fought loyally in the Red Army . Most of the military Cossack associations and traditional clubs did not come into being until after the fall of the Soviet Union. Today the Cossack uniform is often worn again on festive and military occasions.

Languages and cultures of the Caucasian peoples, on the other hand, have been more strongly promoted by the Soviet nationality policy since the Korenizazija phase , which is why the papacha can still be seen most frequently in the countries of the Caucasus. Although it is no longer worn as generally as it was a hundred years ago, it can still often be seen in rural mountain areas, among older people or as part of the consciously worn national costume.

From the 19th century to the first half of the 20th century, the papacha was also popular with the civilian population of Russia and the Soviet Union. From 1940, however, first the Soviet Army and then the militia led, i.e. H. the police used the more practical ushanka with ear flaps (often called "Schapka" in German, which in Russian simply means "hat") as winter headgear, which also spread through the population. Since the Second World War, the Papacha outside the Caucasus and the Cossack associations has largely been ousted by the Ushanka.

literature

- Article of the Great Soviet Encyclopedia (English translation)

- Amjad M. Jaimoukha: The Chechens: a handbook. New York 2005. (English)

- EN Studenezkaja: The clothing of the peoples of the North Caucasus in the 18th-20th centuries. Century . From the scientific journal Nauka : Part 1: Men's clothing in the 18th - first half of the 19th century ; Part 3: Men's clothing from the end of the 19th to the beginning of the 20th century , 1989 (Russian)

Web links

- Video Azerbaijani dancers with papakha (Papaq) and Chokha that the Lezghinka dance, a traditional dance of the Caucasus,

- Tourist site on the Turkmen Papacha

Individual evidence

- ↑ Article Papacha in the Great Soviet Encyclopedia (BSE) , 3rd edition 1969–1978 (Russian)

- ↑ Information in this paragraph cf. Amjad M. Jaimoukha: "The Chechens: a handbook." New York 2005. p. 147 (English)

- ↑ The Homolje region around Žagubica used to be predominantly inhabited by Wallachian shepherds, hence the dominance of sheepskins in folk costumes. Repertoire of the group , video of the dance .

- ^ Collection of Romanian dictionary entries on the origin and distribution of the regional word "Cuşmă".

- ↑ Robert Wixman The Peoples of the USSR , New York, 1984. P. 52

- ↑ See e.g. B. Brix: The Imperial Russian Army in its existence, its organization, equipment and strength in war and peace. Berlin, Posen 1863 p. 37

- ↑ See the militarily binding information in: Generalfeldmarschall Miljutin u. a .: Small pocket reference work for Russian officers ... St. Petersburg 1856. p.916 (Russian)

- ↑ Last paragraph.