Parthian art

Art in the Parthian Empire and in the neighboring areas culturally influenced by the Parthians is referred to as Parthian art . The Parthian Empire existed from around 250 BC. BC to 220 AD in the area of today's Iran and Iraq . Art in the Parthian tradition was also produced after this period and outside of this area.

Art in the Parthian Empire was initially based on Hellenistic art. At the turn of the ages, there was a departure from this tradition. A strong frontality of the figures in painting and sculpture were the main stylistic features from then on. Even in narrative representations, the actors do not look at the object of their action, but instead turn to the viewer. These are features that anticipate the art of the European Middle Ages and Byzantium.

Parthian places and layers are very often ignored during excavations. The research situation and the state of knowledge of Parthian art are therefore still very sketchy.

General

What is now called Parthian art has been known since the end of the 19th century. Since then, numerous sculptures have come to Europe from Palmyra . They mostly depict men in richly decorated robes and women with numerous jewelry. The ruins of the city have often been romantically linked to Queen Zenobia, who is known from literary sources . However, no separate term was created for the art found here, but rather it was considered a local variant of Roman art. The excavations in Dura Europos since the beginning and especially since the 1920s have produced numerous new finds. The classical archaeologist and head of the excavations, Michael Rostovtzeff , recognized that the artistic creation of the first centuries after Christianity in Palmyra, Dura Europos, but also in Iran up to Buddhist India followed the same principles. He called this artistic creation Parthian art . The wide distribution of this art, even outside the boundaries of the Parthian empire, however, raised the question whether this art really still as Parthian what is usually affirmed in research is to describe, since they probably to the art of the Parthian capital of Ctesiphon due is. Nevertheless, the naming of the art of the Parthian Empire and the areas influenced by it in research is inconsistent and cautious. Authors often avoid the term Parthian art and instead prefer to name artistic creation after the cultural or political space. Daniel Schlumberger , who clearly affirmed the term Parthian art , named one of his most important works on the subject of The Hellenized Orient (in the original: L'Orient Hellénisé ; published in Germany in the series Kunst der Welt ). However, the book covers not only Parthian art, but also Greek art in the Orient in general. Hans Erik Mathiesen titled his work on Parthian sculpture: Plastic in the Parthian Empire (in the original: Sculpture in the Parthian Empire ) and excluded cities like Palmyra in his studies. Trudy S. Kawami also named her work on sculpture in Iran: Monumental Art of the Parthian Period in Iran (in the original: Monumental Art of the Parthian Period in Iran ), while Malcom College clearly identified his book on Parthian art as Parthian art (in the original: Parthian Style ).

The Parthian Empire extended over a large area, which was mainly congruent with the territory of today's Iran and Iraq and was home to many different peoples. It existed for over 400 years. On the basis of these assumptions, it is clear that one has to reckon with strong regional differences in the art of this empire and that there has been a considerable development over the centuries. Although there are numerous examples of Parthian art, it should be noted that many important works, including those of the royal court, have survived from some periods, while these are missing for other centuries.

Parthian art is also attested in Syria , in numerous cities, such as Palmyra, Edessa and Dura Europos . Not all of them belonged to the Parthian sphere of influence. In the north, this art seems to have flourished in Armenia, although little has survived. In the south, Bahrain clearly belonged to the Parthian art area, while in the east the transition to Gandhara art is fluid and it is therefore difficult to draw a clear dividing line. In the older research, which viewed Greek art of the Greek Classical period as an ideal, Parthian art was often dismissed as decadent or barbaric art. However, recent research sees this in a more nuanced manner. Parthian art created a lot of new and original things and was trend-setting especially for Byzantine art and the art of the Middle Ages.

The strong frontality of Parthian art is new in the Middle East and seems to be shaped by the experience of Greek art that the Orient went through since the third century BC. Parthian art can therefore be described as an oriental creation after the experience of Hellenistic art .

Stylistic epochs

The art in the Parthian Empire can be roughly divided into two style epochs: a Greek style phase and an actually Parthian one. These style phases did not necessarily follow one another in chronological order, but strong chronological overlaps can be expected. A Greek city like Seleukia on the Tigris produced art in the Greek tradition even longer than the royal cities in the east of the empire like Ekbatana . One example are the coins of Vonones I (6–12 AD). The specimens that were minted in the city of Seleukia on the Tigris show a purely Greek style. The coins of the same ruler from Ekbatana show a style that diverged significantly from Greek models.

Hellenistic phase

At the beginning of Parthian history, their art was still very much committed to Greek art. Particularly in the oldest Parthian capital Nisa , evidence from the early Parthian period could be discovered. Most of the finds there date to the first three centuries BC. There were purely Greek marble sculptures and a number of ivory rhyta in the Hellenistic style, which were figuratively decorated.

The marble statues are on average 50 to 60 cm high. One of them is close to the hair-wringing Aphrodite type . The lower part of the figure is carved in a dark stone, so that the marble body comes into its own. Another female figure is wearing a chiton and a peplos on top , a scarf on the right shoulder. Both statues are likely imports. But they prove the Hellenistic taste of the kings ruling here.

The ornamental ribbons of the Rhyta show scenes from Greek mythology . The style of the figures is purely Hellenistic, even if the figures appear a bit rough in parts and the themes presented from the Greek area apparently were not always understood. Nisa and the province of Parthia, where the Parthian Empire originated, are neighbors to the Greek Bactria and it has therefore been suggested that the Bactrian Greeks in particular influenced the early Parthians artistically or that the Rhyta were even made in Bactria and as Looted property came to Nisa.

A certain mixture of Greek and Iranian elements can be observed in the architecture from the beginning. The architectural jewelry in Nisa is mostly purely Greek. Ionic and Corinthian capitals with acanthus leaves were found . In Nisa discovered stages battlements other hand have their origin in the Iranian space. The square house in Nisa is 38 × 38 meters and consists of a large courtyard, which is adorned by columns on all four sides. Behind it there are elongated rooms on all four sides with benches on the walls. The building may have served as a royal treasury and was made of unfired bricks. He followed local traditions. The plan is reminiscent of Greek palaces. Overall, Nisa appears as a colonial, Hellenistic royal court that hardly differs from other Hellenistic residences at the same time. After all, there are local echoes, especially in the architecture. This can also be seen well in Ai Khanoum , where a royal residence of the Greco-Bactrian kingdom was excavated. Daniel Schlumberger therefore does not want to designate the art of this phase of Parthian history as Parthian .

Without inscriptions and precise excavations, early Parthian and Seleucid buildings can often hardly be distinguished. A large mansion with Ionic and Doric columns still stands in Khurab in Iran. The proportions of the individual components (the columns appear too long and thin) indicate that this house had no purely Greek builders. Its exact date is therefore controversial.

This Hellenistic style of the early Parthian period can also be traced on the coins of the Parthian rulers. The earliest specimens still seem a bit clumsy, but are Greek in style, even if the rulers wear Parthian attributes, which gives the coins an un-Greek appearance. Under Mithridates I , who conquered large parts of the Hellenistic Seleucid Empire, the style of the coins can hardly be distinguished from those of the Hellenistic royal courts. It is also noteworthy that the Parthians only minted silver and copper coins, but no gold coins. The few known gold coins are apparently prestige objects and were minted by local princes in the Parthian sphere of influence.

Parthian style

In addition to the Greek style, pre-Hellenistic traditions in art production are likely to have lived on in numerous places in the Parthian Empire. Two steles were found in Assyria , which are kept in such a style. They each show a standing man in Parthian costume. The figure and the head are shown in profile and are thus in the Mesopotamian tradition. A third stele shows a comparable figure, but now facing the front. One of the stelae in the old Mesopotamian style is dated to a year 324 (12/13 AD or 89/88 BC). In the Parthian Empire different dating systems were in use at the same time and it is not known what era these steles are dated to.

A stele from Dura Europos, which shows the god Zeus Kyrios and the consecrating Seleucus, dates from the year 31 AD . The head and chest of Zeus Kyrios are shown frontally, but the legs from the side. Building reliefs at the Baal temple come from Palmyra and can be dated with certainty to the beginning of the 1st century AD. The temple was dedicated on April 6, 32 AD. Here, too, you can find a new style. The reliefs probably show myths, the content of which is not known from written sources, so the details of the depictions remain incomprehensible to us. The figures are reproduced from the front, even in narrative representations, the figures turn towards the viewer of the reliefs and not towards the other actors within the scene.

Accordingly, a new style can be observed from the time around the birth of Christ in the Parthian Empire, which is characterized above all by the strict frontality of the figures, by a linearism and a hieratic representation. This style turns away from Greek models, but does not follow directly on to pre-Hellenistic art, although the hieratic and linearism can also be found in the art of the ancient Orient. This style seems to have originated in Mesopotamia. The best examples of this now purely Parthian art do not come from the capital, but from places on the edge of the Parthian Empire, such as Dura Europos , Hatra or Palmyra, which does not belong to the Empire .

The emergence of a new style is best seen in the art of coinage. The images of the Parthian kings are often strongly stylized from the time around the birth of Christ. Angular forms replaced the round, flowing forms of the Greek style, although the profile continued to prevail, at least on the coins. From around 50 BC. There were more and more conflicts with the Hellenistic orientated Rome. The new style is therefore perhaps also a conscious departure from the Hellenistic traditions and a reflection on one's own traditions and values.

painting

Parthian art is particularly pronounced in wall painting . Numerous examples are preserved in Dura Europos. A few examples are from Palmyra and Hatra, and fragments of wall paintings have been found in Assyria and Babylon . Much of the wall paintings come from temples and places of worship. In the synagogue and in the church of Dura Europos there are mainly scenes from the Bible . In the miter there are scenes about Mithras . In the other temples in the city, figures of donors and their family members are particularly prominent. Residential buildings were much rarer than painted in the Greco-Roman world. There are banquet and hunting scenes that illustrate and glorify the lives of the nobles.

The figures are now all shown frontally. While in Hellenistic art the frontal representation in painting was only one of many possibilities, it is now the rule in Parthian art. The figures are turned towards the viewer and even in narrative representations one has the feeling that individual figures no longer interact with one another, but are only directed at the viewer. The perspective that existed in Greek art has largely dissolved. A certain spatiality of the figures is only indicated by shading on individual parts of the body. The stand line, which had played an important role in the art of the Near East, no longer has any meaning. The figures now often seem to float freely in space. At least in Dura Europos, most of the paintings were commissioned by private donors. They had their families depicted on the temple walls. The names are written next to their figures.

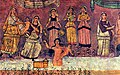

However, there are hardly any examples of figural wall painting from the early phase of Parthian art, when it was still under Greek influence. The beginning of Parthian painting remains unknown for the time being. The wall paintings in the temple of the Palmyrenian gods in Dura Europos can be dated to the end of the first century AD . One scene shows Konon's sacrifice . It belongs to the earliest known Parthian paintings, is one of the highest quality examples of Parthian art and already shows all of its stylistic features. Although the individual figures are arranged in an architecture drawn in perspective, only a few of them stand on the floor; most of them seem to float in space. All figures are shown frontally.

The synagogue of Dura Europos dates back to the years 244/245 , which was mostly painted with scenes from the Old Testament (and for that reason alone is unique). Individual scenes are reproduced in small panels, which in turn, strung together, covered the entire wall. The figures appear a bit more compact than in the temple of the Palmyrenian gods , but in principle show the same stylistic features. They are usually reproduced frontally and often seem to float in space. Perspective architectures hardly appear.

The well-preserved examples of Parthian paintings mostly come from temples and places of worship. Profane painting is not quite as well preserved and therefore less well known. A particular specialty here seem to have been battle and hunting scenes that glorified the lifestyle of the ruling class. The motif of the rider was particularly prevalent. The horses are shown here in a flying gallop . The riders themselves are shown seated on them with their faces turned towards the viewer. Fighting scenes are mostly heavily armed cataphracts , while hunting scenes are rather lightly armed archers. Remnants of such an equestrian scene were found in the palace of Assur and seem to have decorated the representative rooms of the building. Other examples were found in the Mithraeum of Dura Europos. Such riding scenes, in a slightly different form, are then particularly popular with the Sassanids.

Examples of wall painting from Dura Europos

Figure in the mithraic of Dura Europos

plastic

The mentioned style elements can also be found in the sculpture. Sculptures, in limestone, marble and bronze, are mostly designed frontally. Even with group figures, no interaction can be observed, but a complete orientation towards the viewer.

Many examples of Parthian sculpture can be found in Palmyra, where the tombs of the local upper class were richly decorated, depicting the deceased. There were three types of monuments. Locking plates that blocked the entrance to grave complexes; Sarcophagi, which were decorated on the actual coffin box and on the lid show the deceased, mostly lying on their side, at the feast. Few of these images give the impression of a real portrait. The faces of the portrayed appear stylized and transfigured. Men and women are usually shown including the upper body and richly hung with jewelry. Women usually wear Hellenistic clothes, men wear Hellenistic, but also Iranian clothes (especially trousers), as known from the Parthians but also from the Kushana . The latter is hardly ever recorded in Roman Syria . Hardly any three-dimensional sculptures are known from Palmyra, which certainly once existed here, but were probably cast in bronze. They adorned the city streets, but were later melted down. They were erected in honor of deserving and wealthy citizens of the city. Numerous bases of these statues with dedication inscriptions have been preserved. Statues of honor of deserving citizens are also attested by inscriptions from Palmyra for Parthian cities, but not preserved:

- The boules and the people (honor) Soadu , son of Bolyada ... and he was honored by resolutions and statues by the boules and the people and at that time by the caravans and by individual citizens ... because of his repeated charities was honored with four statues on pillars in the Tertradeion of the city at state expense and with three other statues in Charax Spasinu and in Vologesias

In Hatra, on the other hand, there were numerous stone statues depicting deities or local rulers and their family members. The local upper class donated the statues for the temples of the city, where they were found by the excavators. Many of these works are precisely dated by the donors' inscriptions and provide a good chronological framework. Here the sculptor is occasionally mentioned, such as Aba or Schabaz . In addition to works in the classical Greek-Hellenistic tradition (especially of classical deities), they show the people sitting or standing, frontal and in rich Parthian regalia. The men wear shoes, trousers and a tunic over them . Some men wear a kind of jacket over the tunic. Often times a sword can be seen on the right hip and a dagger on the left. Kings wear a tiara with a diadem or just a diadem, on which the image of an eagle can sometimes be found. The right hand is usually raised in a gesture of adoration, the left hand holds a sword or a palm branch in men. Other statues carry a statue of God in both hands. The attention to detail is striking. The patterns of the fabrics, weapons and pieces of jewelry are exactly reproduced.

A woman's head made of marble comes from Susa ( Tehran , Iranian National Museum, Inv. No. 2452), which is one of the most famous works of art from the Parthian territory. The head is slightly larger than life. The face is broad with a long thin nose. The eyeballs are not modeled, but the pupil is indicated by a point. The mouth is softly modeled with rather thin lips. The woman wears a heavy crown on which is the inscription: Antiochus , son of Dryas, made (it) . A veil can be seen on the back. The back of the statue is overall summarily worked, which indicates that the head was designed for the frontal view. It was certainly once set into a separately worked body. The high quality of the work triggered an extensive discussion in research. The modeling of the face is reminiscent of Hellenistic works. The headgear is also known from the Hellenistic area, but certain details are clearly Iranian. Above all, there are numerous examples of the crenellated crown in the pre-Hellenistic Iranian region. Accordingly, it has been assumed that it is a work from the Greco-Roman area that was locally reworked.

Probably the best-known Parthian work of art is the bronze statue of a local prince, which was found at Shami in the Iranian province of Bakhtiyari . It was found by farmers in the remains of a small shrine of Greek gods and Seleucid kings, which possibly served the cult of these gods but also by rulers. The statue is almost completely preserved, only the arms are missing. It is made of two parts and consists of the body and the head, which were worked separately and later put on. The prince stands upright in Parthian clothing with a dagger at his side. He has medium length hair and a mustache. He wears long trousers and a tunic that leaves the chest partially exposed. The figure is again aligned frontally, but seems to radiate power and authority, even if the head seems proportionally a bit too small. Daniel Schlumberger comments that this should certainly not represent a specific individual, but a social type. A typical Parthian nobleman is shown here, as can be seen from the details of the costume. The assignment to a specific person was made via an inscription. The dating is uncertain and goes back to the second century BC. BC to the second century AD. The sitter could not yet be identified, even if Surenas is often called without any evidence . The high quality of the work sparked a lively discussion about the place of manufacture. Guesses range from Susa to an artist from Palmyra who made the work on site.

In addition to these sculptures in a more oriental / Parthian style, there were still sculptures in the Hellenistic style in the Parthian Empire. Many of these works were probably imported from the Roman Empire, as can be assumed for works from Hatra, which only flourished in the second century AD. Most of the works of art in the city were therefore only made here or traded to Hatra at this time. Other sculptures in a more Hellenistic style date from the time when art in the Parthian Empire was strongly oriented towards Hellenistic art or may even come from the time of the Seleucid Empire.

The statue of a goddess comes from Seleukia on the Tigris and is clearly in the Hellenistic tradition. It is a 56 cm high composite figure made of marble, alabaster, bitumen and stucco. The woman wears a chiton and a coat over it. There is a diadem on the head. The figure is conceived from the front, but the position of the legs is atypical for Parthian works. Exact dating of the work is almost impossible, but it was found in layers of the city that the excavators linked to the conquest of the city by the Roman Emperor Trajan (116 AD). So the statue is older. The bronze figure of Heracles comes from the same city. According to the inscription, it comes from the Charakene (part of the Parthian Empire) and came to the city as booty around 150 AD and adorned a temple of Apollo there. The work is clearly Hellenistic, but apparently stood in the Charakene for almost 300 years before it came and found its place in Seleucia. Apparently there was still a demand for works of art in the Hellenistic style in the Parthian Empire.

Examples of Parthian sculpture

relief

In principle, two types of relief can be distinguished. On the one hand there are sculptures with a back plate that are technically and formally very closely related to the full sculpture and were discussed there. There are also flat reliefs in which the figures are only a few centimeters carved out of the stone. These reliefs continue Assyrian and Persian, i.e. pre-Hellenistic traditions and are formally close to painting. Here, as in painting, there are narrative representations. The figures are mostly facing the observer frontally. Especially in the southwest of today's Iran, in the ancient Elymais , there were many Parthian reliefs carved in the rock in this style. Their execution usually looks rather rough. Reliefs in other places, such as B. from Palmyra, on the other hand, appear comparatively mature.

One of the most discussed reliefs is a scene with six men at Hung-i Nauruzi. In the middle stands the largest figure, shown frontally in Parthian costume. To the right of this are three other men, but carved into the stone a little smaller. On the left you can see a rider on a horse. The figure is shown in profile. Another man follows behind the rider, again in profile. The stylistic difference between the horseman portrayed in the more Hellenistic style and the other figures portrayed in the Parthian style led to the assumption that the four men on the right were later carved into the rock. The rider probably represents a king and has been identified with Mithridates I , who lived in 140/139 BC. The Elymais had conquered and under which the Parthian art was still largely Hellenistic. Accordingly, the relief celebrates its victory. However, this interpretation has been contradicted and the rider was seen as a local ruler of the Elymais. Other reliefs in other places often show groups of men, individual men and also the figure of Heracles . A large group of reliefs can also be found at Tang-i Sarvak, arranged on four large, free-standing rocks. There are rows of men again, a man on a kline accompanied by other men or individual men making sacrifices. Dating individual reliefs is often difficult. In research there is a tendency to date more Hellenistic-looking representations earlier, while more Parthian-looking ones later. However, this is not mandatory.

architecture

In the architecture there is a mixture of Greek architectural jewelry with new forms and oriental elements. The Iwan as a new design is particularly noteworthy here, which is a large hall open to a courtyard. This was usually arched. It is a structural unit that is not really closed, but also not completely open. Another peculiarity of Parthian architecture is the alienation of classic building structures.

In the Assyrians a Parthian palace, whose entrance had a courtyard, which was a Greek peristyle was modeled. In Hellenistic architecture, a peristyle was more in the center of the house; here it was converted into an entrance courtyard. The center of the palace was a large courtyard with an ivan on each of the four sides. The facades of the courtyard were richly decorated with a stucco facade.

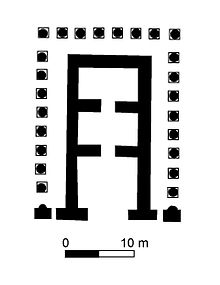

Temple E (also The Temple of the Sun Mithras / Shamashin ) in Hatra is reminiscent of Greco-Roman temples at first glance. The way in which certain classical structures are stringed together is Parthian. A cella stands on a podium and is surrounded on three sides by two rows of columns. The front is adorned by a staircase that is flanked on the sides by the outer row of columns. The outer row of columns stands on the base and is adorned with compositional chapters. The inner row of columns stands on the podium and has Ionic capitals. The gable of the temple front shows an arch. The architraves and gables are richly decorated with architectural decorations.

A comparable temple was found in Assyria. It consists of three rooms one behind the other with the Holy of Holies as the last room. Pillars are arranged around the temple. To that extent it is similar to a Greek temple. The particular Parthian element, however, is the fact that the columns are only on three sides and that the front in particular was not decorated with columns. With certain types of Greek temples it also happened that one or more sides managed without columns, but the front or entrance side was always decorated with these.

Other temples seem to be based on ancient oriental traditions. In the center of the Hatra temple complex are a number of juxtaposed iwans. There are two large ivans, each flanked by several small rooms. There are also six smaller ivans. The complex also stands on a podium. The facade is structured by pilasters. There is, in turn, rich architectural jewelry, especially the heads of people, but also of animals.

The temple of Gareus still stands in Uruk today . It is made of fired bricks; its dimensions are about 10 meters long and 8 meters wide. The interior resembles Babylonian temples with a vestibule and a cella. The cult niche with a podium in front is also Babylonian. The facade of the building is decorated with blind arcades. In front of the building were six columns with Ionic capitals. Other architectural decorations consisted of egg bars and lesbian kymatia. A frieze shows dragons and looks more oriental. All in all, there is again a mixture of Hellenistic and oriental elements.

The temples in Dura Europos are architecturally rather undemanding. They had various rooms arranged around a courtyard. The Holy of Holies was mostly at the rear of the complex and could be highlighted by columns at the entrance. The other rooms around the courtyard were probably used for banquets, as priestly apartments or as places of worship. The Holy of Holies was often magnificently painted.

The temples in Palmyra appear Hellenistic-Roman at first glance and it is often only small details that distinguish them from those in the Mediterranean world. Overall, the architecture of the city is therefore more Roman-Syrian with a few peculiarities that are typically Parthian . The great Baal Temple stands within a walled courtyard, which is adorned with columns and forms a rhodic peristyle . The actual temple in the center of the complex is a Peripteros temple. What is unusual, however, is that the main entrance with a flight of stairs is on the long side of the temple and not on a short side. The roof of the temple is decorated with step battlements.

Various types of graves were found in the necropolis of Palmyra. Architecturally interesting are burial towers, which are also known from Dura Europos and other places on the Euphrates , but not from other parts of Syria . They are square buildings that were up to five stories high. The interior offered space for several hundred dead and in Palmyra was often richly decorated with sculptures.

Plenty of ornamental stucco was used as structural decoration in Parthian buildings , which on the one hand continues Greek patterns, but also has its own new Parthian patterns. The stucco itself was taken over by the Greeks, but is now particularly popular and many architectural parts are now only worked in stucco, probably also to beautify aesthetically rather undemanding mud brick walls. There are columns and ornamental bands placed on the wall. The stucco columns in particular are usually only placed on the wall and are purely ornamental elements. They have no supporting function and do not try to add depth to the wall, as was customary in Greco-Roman architecture. The building materials were mostly based on the building materials that were available on site. In Mesopotamia, therefore, many buildings were built from bricks, which were then stuccoed. In Hatra and Palmyra, however, limestone is the predominant material. Here, on the other hand, there is less evidence of stucco. Arches were used abundantly in Parthian architecture, and the ivans in particular are mostly vaulted.

Terracottas and cabaret

A large number of terracotta figures and figures made of other materials were found at all Parthian sites. These can also be stylistically divided into two groups. There are, on the one hand, purely Greek or Greek-influenced figures and, on the other hand, those in a Near Eastern and later Parthian style. Heracles figures were particularly popular with the Greek types, as he was identified with the Parthian god Verethragna . Naked statues of women, mostly in the Greek tradition, may have served as fertility idols. Parthian types are mainly recumbent and standing male figures.

The main find where Parthian terracottas were observed in detail stratigraphically is Seleukeia on the Tigris. Surprisingly, both Greek and Oriental types appear side by side in almost all epochs of Parthian history. A similar observation could be made with the figures from Susa that were only recently published.

Interpretation of the frontal representation

The frontal representation of figures in painting, relief and sculpture is not an invention of the Parthians. In the ancient Orient the profile view predominated, but there was also a frontal view, especially in sculpture. The frontal view in the flat screen was used in the ancient Orient to emphasize certain figures. Daniel Schlumberger argued that these are always characters to whom special value was attached, who in some way were perceived as real. The figures, gods and heroes depicted in the front were not simply copies of life in a different material; instead, they were these figures and could participate in life with their gaze on the viewer. They were practically present . Art in the ancient Orient, but also in archaic Greece, only knew the frontal and profile views. It was not until the classical Greeks that intermediate stages, especially the three-quarter view, were introduced. Representations of the classical Greeks tried to reproduce the illusion of life in all its forms. The figures are completely occupied with themselves and ignore the viewer. The frontal representation also occurs here, but it is only one of many possibilities. Parthian art has certainly taken over the frontality from Hellenistic art, but the Parthians seem to have reverted to the presence of the ancient Orient in their art . Parthian art did not try to capture an illusion and the volatility of life. Rather, efforts were made to give the figures durability. One tried to capture the real content of life and not just the outer shell. With their gaze directed at the viewer, the figures force their attention on him. As a result, they often appear highly transcendent .

End and outlook

In the second century AD, the Parthian Empire had to fight numerous internal and external enemies. The Romans traveled through Mesopotamia several times and the plague (see Antonine plague ) seems to have ravaged the Parthian Empire. These crisis factors obviously also had a negative impact on art production. While many of the better Parthian works of art radiate sublimity and a certain transcendence, despite or precisely because of their distance from nature, certain signs of decay are unmistakable from the late second century AD. The coin legends are barely legible, and a relief comes from Susa, the representation of which can actually only be described as recorded .

Around 226 the Parthian rule was overthrown by the Sassanids . In Persia and large parts of Mesopotamia, Parthian art thus disappeared, even if certain art traditions, such as the stucco reliefs and the equestrian scenes, survived under the Sassanids. In Syria , however, Parthian art continued to live even after the fall of the Parthians, although it must be borne in mind that cities such as Palmyra and Dura Europos did not belong to the Parthian sphere of power and therefore did not begin a new era for these places with the rise of the Sassanids. Only with the fall of these cities (Hatra, shortly after 240; Dura Europos, around 256; Palmyra 272) does Parthian art disappear from our field of vision. In Syrian and Armenian book illumination from the 6th to 10th centuries, however, many Parthian elements can be found that testify to the continued existence of this art.

Above all, the strict frontality of Parthian art can also be found in the art of Byzantium and in the European Middle Ages, so that one can rightly say that Parthian art primarily influenced Christian art for the following 1000 years. Much has been developed in architecture, like the Ivan, which should endure in the Islamic world. In addition, Parthian art also radiated strongly to the east and probably had a significant share in Buddhist art and thus indirectly even reached China.

See also

Individual evidence

- ^ Schlumberger: The Hellenized Orient. P. 72.

- ↑ Rostovtzeff: Dura and the Problem of Parthian Art

- ^ Schlumberger: The Hellenized Orient. Pp. 73-75 (however, he assigns the works in the Parthian Empire in the Hellenistic tradition to Greek art)

- ^ MAR Colledge: The Art of Palmyra. London 1975.

- ↑ Aphrodite from Nisa, Excavations of Staraia Nisa , on The Circle of Ancient Iranian Studies (CAIS)

- ↑ Stawiskij: The peoples of Central Asia. P. 58, Fig. 15.

- ^ Colledge: The Parthians. P. 148.

- ↑ Stawiskij: The peoples of Central Asia. Pp. 59-60; Boardman: The Diffusion of Classical Art , p. 90.

- ↑ plan of the excavations; the square house in the far north

- ↑ Stawiskij: The peoples of Central Asia. Pp. 52-55; Schlumberger: The Hellenized Orient. P. 38.

- ^ Schlumberger: The Hellenized Orient. Pp. 38-39.

- ^ Ernst Herzfeld : Iran in the Ancient East , Oxford 1941, fig. 380, 383; Khore Manor House

- ↑ Veronique Schiltz: Tillya Tepe, Tomb I. In: Friedrik Hiebert, Pierre Cambon (ed.). Afghanistan: Hidden Treasures from the National Museum, Kabul . National Geographic, Washington, DC 2008, pp. 292–293 No. 146, ISBN 978-1-4262-0295-7 (imitation in gold of a coin of Gotarzes I. )

- ^ Mathiesen: Sculpture in the Parthian Empire. 190-191, catalog nos. 158, 159

- ^ Mathiesen: Sculpture in the Parthian Empire. 191-92, catalog no.160

- ↑ Istanbul, Oriental Museum 1072/4736, Mathiesen: Sculpture in the Parthian Empire. No. 159

- ↑ Schlumberger, Der Hellenized Orient , p. 124 fig. 43

- ^ Mathiesen: Sculpture in the Parthian Empire. 27, 197

- ^ Colledge: The Parthians. P. 150.

- ^ Schlumberger: The Hellenized Orient. Pp. 89-90, 200-201

- ^ Colledge: The Parthians. P. 148; Mathiesen: Sculpture in the Parthian Empire , p. 27.

- ^ Schlumberger: The Hellenized Orient. P. 203.

- ^ Schlumberger: The Hellenized Orient. Pp. 10-11; Boardman: The Diffusion of Classical Art in Antiquity , p. 86.

- ^ Maura K. Heyn: The Terentius Frieze in Context. In: Lisa R. Brody, Gail L. Hofman (Eds.): Dura Europos , Boston 2011, ISBN 978-1-892850-16-4 , p. 223.

- ^ Wall in the synagogue

- ^ Colledge: The Parthians. Blackboard. 69

- ↑ see example

- ^ Schlumberger: The Hellenized Orient. Pp. 86-87.

- ^ Schlumberger: The Hellenized Orient. Pp. 98-99.

- ^ Schlumberger: The Hellenized Orient. P. 90.

- ↑ Translation from: Monika Schuol: The Charakene. A Mesopotamian kingdom in the Hellenistic-Parthian period . Steiner, Stuttgart 2000, ISBN 3-515-07709-X , (Oriens et Occidens 1), (Simultaneously: Kiel, Univ., Diss., 1998), pp. 67-68.

- ↑ Images of statues from Hatra, on The Circle of Ancient Iranian Studies (CAIS)

- ^ Mathiesen: Sculpture in the Parthian Empire. P. 71 (list of dated sculptures)

- ↑ The Melammu Project Priestess of Isharbel in Hatra ( Memento of the original from June 17, 2017 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ Mathiesen: Sculpture in the Parthian Empire. Pp. 74-75.

- ↑ Kawami: Monumental art of the Parthian period in Iran. Pp. 168-169.

- ↑ Kawami: Monumental art of the Parthian period in Iran. Pp. 53-54.

- ^ Mathiesen: Sculpture in the Parthian Empire. P. 89, n.11

- ↑ image of the head

- ^ Schlumberger: The Hellenized Orient. P. 164.

- ^ Mathiesen: Sculpture in the Parthian Empire. P. 167 n.11 (list of various dates)

- ^ Mathiesen: Sculpture in the Parthian Empire. P. 166.

- ↑ picture of the statue

- ^ Wilhelmina Van Ingen: Figurines from Seleucia on the Tigris: discovered by the expeditions conducted by the University of Michigan with the cooperation of the Toledo Museum of Art and the Cleveland Museum of Art, 1927-1932, Ann Arbor, Mich .: University of Michigan Press, 1939, p. 354, Br. 1652, Pl. 88, 644; A. Eggebrecht, W. Konrad, EB Pusch: Sumer, Assur, Babylon , Mainz am Rhein 1978, ISBN 3-8053-0350-5 , No. 163

- ↑ The statue is shown in: Josef Wiesehöfer: Das antike Persien , Zurich 1998, ISBN 3-491-96151-3 , plate XVIb, c

- ↑ Rock reliefs in Behistun

- ^ Mathiesen: Sculpture in the Parthian Empire. Pp. 119-121.

- ↑ Colledge: Parthian art. P. 92.

- ^ Mathiesen: Sculpture in the Parthian Empire. Pp. 125-130.

- ^ Mathiesen: Sculpture in the Parthian Empire. Pp. 130-146.

- ^ Schlumberger: The Hellenized Orient. Fig. 39 on p. 121.

- ^ Schlumberger: The Hellenized Orient. Fig. 40 on p. 122.

- ↑ Pictures of the temple on The Circle of Ancient Iranian Studies (CAIS)

- ↑ Summer: Hatra. Pp. 51-57.

- ^ Colledge: The Parthians. P. 126, Fig. 32

- ↑ Summer: Hatra. Pp. 63-73.

- ^ Schlumberger: The Hellenized Orient. Pp. 151-153, Figs. 51-52

- ^ MK Heyn: the Terentius Frieze in Context. In: Lisa R. Brody, Gail L. Hoffman (Eds.): Dura Europpos , Boston 2011, pp. 221–222.

- ^ Schlumberger: The Hellenized Orient. Pp. 80-84.

- ^ Schlumberger: The Hellenized Orient. Pp. 85-86.

- ^ Colledge: The Parthians. Pp. 107-108.

- ↑ Minerva July / August 2003 (PDF; 11.2 MB)

- ^ Schlumberger: The Hellenized Orient. P. 156; the figures are fully published in: Wilhelmina Van Ingen: Figurines from Seleucia on the Tigris: discovered by the expeditions conducted by the University of Michigan with the cooperation of the Toledo Museum of Art and the Cleveland Museum of Art, 1927-1932 , Ann Arbor , Mich .: University of Michigan Press, 1939.

- ↑ L. Martinez-Sève: Les figurines de Suse. Réunion des musées nationaux. Paris 2002, ISBN 2-7118-4324-6 .

- ^ Schlumberger: The Hellenized Orient. P. 204.

- ^ Schlumberger: The Hellenized Orient. Pp. 206-207.

- ↑ Stele from Susa, dated 215 (picture is reversed)

- ^ Schlumberger: The Hellenized Orient. P. 215.

literature

- Michael Rostovtzeff : Dura and the Problem of Parthian Art. Yale Classical Studies V, New Haven 1935.

- Harald Ingholt : Parthian sculptures from Hatra: Orient and Hellas in art and religion . The Academy, New Haven 1954.

- Roman Ghirshman : Iran. Parthians and Sasanids . CH Beck, Munich 1962. ( Universum der Kunst 3)

- Bruno Jacobs (Ed.): "Parthian Art" - Art in the Parthian Empire . Wellem Verlag, Duisburg 2014.

- Daniel Schlumberger : The Hellenized Orient. Greek and post-Greek art outside the Mediterranean . Holle Verlag, Baden-Baden 1969. (1980, ISBN 3-87355-202-7 )

- Daniel Schlumberger: Descendants of Greek Art Outside the Mediterranean. In: Franz Altheim , Joachim Rehork (ed.): The Hellenism in Central Asia . Darmstadt 1969, pp. 281-405. (= Paths of Research , Vol. 91)

- Malcolm AR Colledge: The Parthians. Thames and Hudson, London 1967.

- Malcolm AR Colledge: Parthian art. London 1977.

- Boris j. Stawiskij: The peoples of Central Asia in the light of their art monuments. Keil Verlag, Bonn 1982, ISBN 3-921591-23-6 .

- Trudy S. Kawami: Monumental art of the Parthian period in Iran. Brill, Leiden 1987, ISBN 90-6831-069-0 .

- Hans Erik Mathiesen: Sculpture in the Parthian Empire. Aarhus 1992, ISBN 87-7288-311-1 .

- John Boardman : The Diffusion of Classical Art in Antiquity. Thames and Hudson, London 1994.

- Michael Sommer : Hatra. History and culture of a caravan town in the Roman-Parthian Mesopotamia . Mainz 2003, ISBN 3-8053-3252-1 .