Plautian

Plautian († January 22, 205 in Rome ), with full name Gaius Fulvius Plautianus , was a Roman Praetorian prefect at the time of Emperor Septimius Severus and father-in-law of his son Caracalla . Through the trust of the emperor, he gained an extraordinary position of power. But he was defeated in the power struggle with Caracalla, who had him murdered.

Life

Origin and advancement

Plautian was a North African of low origin. He came from Leptis Magna , the hometown of Septimius Severus, with whom he was close friends and probably related. He probably belonged to the family of Severus' mother, Fulvia Pia. He is probably to be equated with a man - apparently a procurator - whose name is passed down as "Fluvius" (apparently a typo). According to the historian Cassius Dio, this procurator was tried and convicted of corruption by the future emperor Pertinax , when he administered the province of Africa as proconsul (188-189); but later he received an important office from Pertinax when he was emperor for a short time in 193, supposedly as a favor to Severus. The historian Herodian reports of a conviction of Plautian "for rebellion and many other offenses" .

Plautian began his career in Rome as a Roman knight . Apparently he was given the office of praefectus vehiculorum - perhaps already under Emperor Commodus or under Pertinax - and thus took on administrative tasks in the area of traffic and transport. Presumably he then became procurator XX hereditatium , i.e. was responsible for collecting inheritance tax. After that - perhaps already in 193 under Pertinax or under his successor Didius Julianus , at the latest in 195 under Septimius Severus - he obtained the office of praefectus vigilum , the commander of the Roman fire brigade and security police.

Role as Praetorian Prefect

In the civil war between Severus and the counter-emperor Pescennius Niger , Plautian was commissioned to arrest the counter-emperor's sons in 193. Plautian was appointed Praetorian Prefect by June 197 at the latest, probably as early as 195 or 196. Although he was not a senator , he was honored with the ornamenta consularia (insignia of rank of a consular ). He accompanied the emperor on campaigns and trips.

Since Plautian had the full confidence of Severus, he rose to immense power and acquired great wealth, some of which came from the oil trade. He made the later Emperor Macrinus , who was also a North African, to manage his fortune . Plautian received the title vir clarissimus (“highly respected man”), which was actually reserved for members of the senatorial rank, was thus elevated to the rank of senatorial honor, but this honor did not mean admission to the senate. He had his colleague Quintus Aemilius Saturninus killed, so that he was henceforth the sole Praetorian prefect. He held this office until his death.

Plautian reached the height of his power when, as a result of his great influence on the emperor, his daughter Fulvia Plautilla was betrothed to Caracalla, the older of the two emperor's sons, and married in 202, although Caracalla, who viewed and hated Plautian as a rival, did not want this . In addition, Plautian was accepted into the Senate; his family was now included in the patrician family . Even as a senator, he remained Praetorian prefect, although this office was chivalrous. No Praetorian prefect had ever achieved such a position of power before. Cassius Dio, a staunch opponent of Plautian, describes his power as emperor-like and accuses him of sexual debauchery.

Plautian was even able to push back the influence of the Empress Julia Domna , with whom he was enemies. He treated her disrespectfully, collected alleged incriminating material with which he wanted to prove that she was indecent, and intrigued against her with the emperor. As a result, she was put on the defensive and was temporarily forced to a withdrawn way of life.

In 203 Plautian became full consul with the emperor's brother, Publius Septimius Geta . He also served as pontiff . Many statues were erected for him, also in Rome and by decision of the Senate; According to Cassius Dios, they were more numerous and sometimes larger than the imperial statues.

Fall

After a temporary resentment of Severus because of the too numerous statues of the prefect, the power struggle with Caracalla finally brought down Plautian. Caracalla started an intrigue. He used the help of his former tutor Euodus . Euodus had three centurions accuse Plautian of plotting to murder Severus and Caracalla; they claimed the prefect had instigated them and seven other centurions in the assassination. Severus managed to convince that Plautian had such a murder plot in mind. Plautian was summoned to the palace on January 22, 205, where he was killed in the presence of the emperor on the orders of Caracalla, without being able to defend himself beforehand. The body was thrown down from the imperial palace on the street and was not buried until later on the emperor's orders. Some of the victim's confidants were executed.

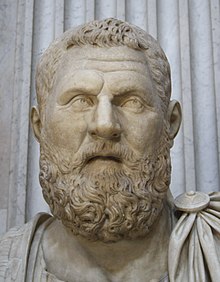

Plautian fell into the damnatio memoriae (erasure of memory), his statues were destroyed, his name was erased from inscriptions. No clearly identifiable portrait of the prefect has survived. His son Gaius Fulvius Plautus Hortensianus and his daughter were exiled to Lipari and killed in 211 on the orders of Caracalla. His property was confiscated; it was so extensive that a special procurator was appointed to manage it. One of the confiscated properties was Plautian's spacious house on the Quirinal , which has been archaeologically identified.

literature

- Sarah Bingham, Alex Imrie: The Prefect and the Plot: A reassessment of the murder of Plautianus . In: Journal of Ancient History 3, 2015, pp. 76–91.

- Anthony R. Birley : Septimius Severus. The African Emperor . 2nd revised edition, London 1988, ISBN 0-7134-5694-9 .

- Mireille Corbier: Plautien, comes de Septime-Sévère . In: Mélanges de philosophie, de littérature et d'histoire ancienne offerts à Pierre Boyancé . Rome 1974, pp. 213-218.

- Werner Eck : C. Fulvius Plautianus . In: The New Pauly (DNP). Volume 4, Stuttgart 1998, Col. 708f.

- Fulvio Grosso: Ricerche su Plauziano e gli avvenimenti del suo tempo . In: Atti della Accademia Nazionale dei Lincei. Rendiconti. Classe di Scienze morali, storiche e filologiche 23, 1968, pp. 7-58.

- Markus Handy: The Severers and the Army . Berlin 2009, pp. 44–49.

- Barbara Levick : Julia Domna. Syrian Empress. London 2007, pp. 74-80.

- Robert Sablayrolles: Libertinus miles. Les cohortes de vigiles . Rome 1996, pp. 493-495.

- Arthur Stein : C. Fulvius Plautianus . In: Prosopographia Imperii Romani (PIR), 2nd edition, part 3, Berlin 1943, pp. 218-221 (F 554).

Web links

- Jona Lendering: Gaius Fulvius Plautianus . In: Livius.org (English)

Remarks

- ↑ Herodian 3,10,5-6.

- ↑ Cassius Dio 74.15.4. See Anthony R. Birley: The African Emperor. Septimius Severus , 2nd, expanded edition, London 1988, pp. 93, 221.

- ↑ Herodian 3,10,6.

- ^ Anthony R. Birley: The African Emperor. Septimius Severus , 2nd, expanded edition, London 1988, pp. 93, 221; Markus Handy: Die Severer und das Heer , Berlin 2009, pp. 45, 48f.

- ↑ Robert Sablayrolles: Libertinus miles. Les cohortes de vigiles , Rome 1996, p. 493f. and note 62; Anthony R. Birley: The African Emperor. Septimius Severus , 2nd, expanded edition, London 1988, pp. 121, 221; Markus Handy: The Severers and the Army , Berlin 2009, p. 49.

- ↑ Cassius Dio 76,14,3; Herodian 3,10,6.

- ↑ CIL 11, 1336 .

- ↑ Cassius Dio 77,1,2.

- ↑ CIL 11, 8050 .

- ↑ Cassius Dio 76.15, 6-7.

- ↑ CIL 6, 1074 .

- ↑ Cassius Dio 76,14,6f. For the inscription of a statue of Plautian from Asia Minor see Rudolf Haensch : An honorary inscription for C. Fulvius Plautianus: MAMA X 467 . In: Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik , Vol. 101, 1994, pp. 233-238 ( online ; PDF; 91 kB).

- ↑ Cassius Dio 76,16,2; see. Herodian 3,11,3.

- ↑ Cassius Dio 77.2.1-77.4.5. Compare the less credible description in Herodian 3: 11, 4–3, 12, 12.

- ↑ Cassius Dio 77.4.5; see. Herodian 3:12, 12.

- ↑ Cassius Dio 76,16,4.

- ↑ On the implementation of Plautian's damnatio memoriae see Eric R. Varner: Mutilation and Transformation. Damnatio Memoriae and Roman Imperial Portraiture , Leiden 2004, pp. 161–164.

- ↑ Cassius Dio 77,6,3; 78.1.1.

- ↑ Eric R. Varner: Mutilation and Transformation. Damnatio Memoriae and Roman Imperial Portraiture , Leiden 2004, p. 161 and note 46.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Plautian |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Fulvius Plautianus, Gaius; Plautianus, Gaius Fulvius |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Praetorian Prefect |

| DATE OF BIRTH | 2nd century |

| DATE OF DEATH | January 22, 205 |

| Place of death | Rome |