Puʻu ʻŌʻō

| Puʻu ʻŌʻō | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Young Puʻu ʻŌʻō with a height of 40 meters on June 29, 1983 |

||

| height | 698 m | |

| location | Hawaii | |

| Mountains | Kīlauea volcano | |

| Coordinates | 19 ° 23 '11 " N , 155 ° 6' 18" W | |

|

|

||

| Type | Welding slag cone | |

The Puʻu ʻŌʻō ([ puʔu ʔoːʔoː ], in German geological literature mostly Pu'u 'O'o , in travel literature also Puu Oo ) is a 698 m high cinder and sweat cinder cone in the eastern rift zone of the Kīlauea volcano on the largest Hawaiian island Big Iceland . The cone was formed in the course of the Puʻu-ʻʻō-Kūpaianaha eruption , which began on January 3, 1983 and ended in 2018.

Surname

The name Puʻu ʻŌʻō is often translated as "hill of the ʻŌʻō ", a probably extinct bird. According to another tradition, it was derived from another meaning of the Hawaiian word ʻŌʻō , which means a digging stick. Since the volcano goddess Pele, according to mythical tradition, created volcanoes with her magic wand pāoa , this is probably the originally intended name.

Intermediate result of the current series of eruptions

The duration of the eruption, the volume ejected and the nature of the material released, the proportion of magnesium oxide in which varies between 5.7 and 10 percent by mass , represents a special feature within the records of the activities of Kīlauea going back around two centuries.

The Puʻu ʻŌʻō creates lava tubes . Due to the thermal insulation effect , they only slowly cool the basalt lava flows, which are initially up to 1250 degrees Celsius. On the 10-kilometer way to the sea, their temperature only drops by about 10 degrees. When it enters the sea, into which it often falls from a height of over 100 meters, the lava still has a temperature of well over 1100 degrees.

Origin of the Puʻu ʻŌʻō

The eruption began on January 3, 1983, when after a 24-hour swarm of earthquakes, crevices formed in the Nāpau Crater within the Hawaii Volcanoes National Park and expanded eight kilometers in a northeast direction over the next few days. Lava erupted from these crevices - with temporary interruptions - during the first few months until activities increasingly concentrated on the eruption channel 1123 on the border of the national park - later known as the "Puʻu-ʻŌʻō Canal". The canal erupted roughly every three to four weeks for less than 24 hours for the next three years. A special feature of these early phases were lava fountains that hurled magma up to 470 meters above sea level.

By the fountain was called primarily 'A'ā -Lava released, the more viscous and more crystalline type of the two types of Hawaiian lava. The 'A'a currents released were usually three to five meters thick and moving at a speed of between 50 and 500 meters per hour, getting faster and narrower on steep slopes. Within 13 hours, the lava reached the part of the Royal Gardens , which is located six kilometers south-east on a steep slope , where it fell victim to a total of 16 houses in 1983 and 1984. However, the eruptions were too short to reach the south coast highway or the ocean itself.

The ejected material from the lava fountains gradually accumulated to form a slag and sweat slag cone, which, at a height of 255 meters, was more than twice as high as any other cone in the eastern rift zone. This cone, known as Puʻu ʻŌʻō, was unusually asymmetrical, as the prevailing winds piled up the ejected material mainly on the southwest side.

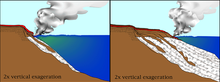

Relocation of the eruption to the Kūpaianaha

In July 1986 the previous eruption channel broke open so that the lava was looking for a new route: the Kūpaianaha Canal, three kilometers northeast of the Puʻu ʻŌʻō. This also ended the lava fountains and began a five and a half year phase in which lava flowed almost continuously. Above the Kūpaianaha a lava lake formed , which created a wide and low shield through frequent overflow , the maximum height of 55 meters was reached in less than a year. After a few weeks of continuous eruptions, a roof formed piece by piece over the main canal leading out of the lake through lateral lava deposits, so that finally a lava tube was created. The heat of a lava flow is preserved through such a tube and pahoehoe flows are formed , which are far more fluid than ʻAʻā flows. When cold, these have a flat and smooth, sometimes rope-like or corrugated surface and are therefore also referred to as "knitted lava".

The Pahoehoe currents released through the tube spread towards the twelve kilometers southeast of the coast, but required three months for the same distance that the ʻAʻā currents of the Puʻu ʻŌʻō had previously covered in one day. At the beginning of November 1986 the streams were first visible from the Kapa'ahu community. During November, the Kūpaianaha lava drew a swath through Kapaʻahu and clogged the coastal highway before finally flowing into the sea at the end of November. A few weeks later, the lava flow shifted to the east and buried 14 houses on the northwestern edge of the village of Kalapana within a day . However, this lava flow stopped after the lava tube clogged near the eruption canal.

Over the next three years, pahoehoe currents destroyed homes on both sides of the continually widening drainage area. Initially the direction of these currents was guided by topographical conditions, but over time, high landmarks were also flooded.

From mid-1987 to the end of 1989, much of the lava flowed directly into the sea. Steam explosions caused by the heat of the entry ground the cooling rock into black, glass-like sand, which collected downstream in bays to form new beaches and formed banks on steep slopes below the water level, which over time expanded the land area. In the spring of 1990, the pipe system to the sea gradually broke open, so that there were more currents on the surface. These penetrated new areas and buried the Waha'ula visitor center and adjacent houses in the Hawaii Volcanoes National Park .

The eruption changed in 1990 when twelve breaks, each lasting one to four days, interrupted the eruptions that had been continuous until then. At the same time, the most devastating phase of the eruption began. In March 1990, the lava flows turned again towards Kalapana, known for its historic sites and black beaches. At the end of summer, the more than a hundred houses in the village were buried under 15-25 meters of lava. Further east, the lava flowed into the sea, replacing the previously palm-fringed Kaimu Bay with a magma plain that protruded 300 meters above the original land border. At the end of 1990 a new lava tube was formed, which led the currents away from Kalapana into the national park, where they flowed again into the sea.

During this five and a half year dominance of the Kūpaianaha, a crater with a diameter of about 300 meters was formed at Puʻu ʻŌʻō through a series of collapses . This crater initially led sporadically from 1987, but from 1990 onwards, a lava lake permanently.

In the course of 1991 the Kūpaianaha released less and less lava, while the activity and level of the lava lake rose continuously at Puʻu ʻŌʻō. In November 1991, lava emerged from new crevices between Kūpaianaha and Puʻu ʻŌʻō for three weeks, which further weakened the eruption on Kūpaianaha until this eruption channel finally went out on February 7, 1992.

Return to the Puʻu ʻŌʻō

Ten days after the extinction of the Kūpaianaha, the volcanic activity was again concentrated on the Puʻu ʻŌʻō. On its western flank, low lava fountains emerged from a crevice. This was the first in a series of new outbreak channels that have been active for a total of eight years. As before on the Kūpaianaha, the lava came out calmly and almost continuously. The activities of the mountain created a 45 meter high, one kilometer diameter lava shield on the western flank.

In November 1992, the lava crossed the Chain of Craters road in Hawaii Volcanoes National Park and entered the sea at Kamoamoa, 11 kilometers from the eruption channel. This archaeological site - like the national park's campsite - was buried by pahoehoe torrents over the next few months. Here, too, a black sand beach was formed when the magma entered the Azura Sea . Between the end of 1992 and January 1997, lava tubes discharged lava almost continuously into the sea and widened the Kamoamoa field, most of which lay within the national park. From 1993 onwards, the lava, which slowly paved its way through the tephra , led to collapses on the western flank of the Puʻu ʻŌʻō. The largest resulting crater, the "Great Pit", encompassed almost the entire western flank towards the end of 1996.

Collapse of the western flank

On the night of January 30, 1997, the eruption channel of the Puʻu ʻŌʻō emptied, causing the bottom of the crater and then the western flank of the cone to collapse due to the lack of counterpressure from the magma. Some time later, new crevices broke open, from which lava flowed briefly in and around the Napau crater. This phase was over after 24 hours. The collapse left a large breach in the western flank of the mountain and the resulting rubble flattened the crater to a depth of 210 meters. In the following 23 days, no more active lava could be observed at the eruption site.

The next phase began on February 24, 1997, when another lava lake formed at the bottom of the Puʻu ʻŌʻō crater. A month later, lava also emerged from new eruption channels on the west and southwest flanks of the cone. In mid-June 1997, the lava level inside the crater rose above the rim of the crater for the first time in eleven years. Lava flowed over the east side of the mountain and spread up to one and a half kilometers down the slope in the rift zone. After a short time, however, the lava was already draining through channels in the crater floor, so that no further currents came over the rim.

In July 1997, lava flows again reached the ocean and flowed into the ocean near the eastern border of the Hawaii Volcanoes National Park in two places, Wahaʻula and Komakuna, until the beginning of 1999.

On January 14, 1998, the level within the Puʻu ʻŌʻō rose again drastically, so that again lava flowed over the rim of the crater. At the same time, lava emerged in the form of fountains and streams from some collapse craters on the southern flank. In the further course of the year this flowed directly into the pipe system around the Puʻu ʻŌʻō. The currents continuously eating through the tephra of the cone increasingly destabilized the Puʻu ʻŌʻō, so that in December 1997 a new collapse crater formed on the southwest flank of the cone. This “Puka Nui” crater already had a diameter of more than 175 meters at the end of 1998.

Clogged pipe system

On September 12, 1999, the earthquake and the emptying summit heralded the penetration of magma into the upper eastern rift zone of Kīlauea. As a result, the pressure of the Puʻu-ʻŌʻō Canal eased and the normal eruption was interrupted for eleven days - the longest pause since the cone collapsed in 1997.

The eruptions resumed with a few weeks of increased activity in and around the crater. Active lava again covered a large part of the crater floor and about ten new cinder cones formed inside and on the flanks of the cone. Before this event, the lava flow through the tube system was stable for twelve months, during the break part of the system around eight kilometers from the coast was permanently blocked. When the eruption resumed, the surface lava flowed over the blockade and formed large lava lakes over the blocked tube. The mostly very short streams emerging from this created shield structures with a height of 5–20 meters and a diameter of up to 500 meters, which combined to form a ridge along the tube. Longer streams reached the sea at Highcastle and Laeapuki in mid-December. However, they were so short-lived that as early as the spring of 2000 the active junctions had shifted to the eastern side of the river basin. Over the next five months, lava poured into the sea over the entire area from the eastern edge of this area to Kamokuna.

In the spring of 2000, lava flows crossed the eastern border of the national park and destroyed several abandoned houses in the Royal Gardens there in the following two years. At times the confluences into the sea stopped, a new stream at E. Kupapaʻu, but this pause ended at the eastern border of the river basin. This was the first time since 1991 that lava flowed into the sea outside the national park, which was opened to the public as a tourist attraction in August 2001. Within the first week after opening, 400 vehicles per day traveled across the Kūpaianaha area produced between 1987 and 1991. A second confluence formed in late September 2000 at Kamoamoa. Both streams remained active through the end of the year.

Increased formation of shields and hornitos

At the end of 2001, the lava flow through the tube leading to the coast decreased, so that from January 2002 no further lava flowed into the sea, but instead flowed increasingly from the upper parts of the tube to the surface. As in 1999, lava lakes and lava shields formed along the tube. At the end of March 2002, eight main shields formed a continuous ridge 2.7 kilometers long and 1.5 kilometers wide.

In the first three months of 2002, hornitos - chimney-like eruption cones - formed in many places on the tube, which were often between eight and twelve meters high. In addition, the activity in and around the Puʻu ʻŌʻō increased during this time. In April and May 2002, several cinder cones formed around the Puka Nui, the floor of which was covered by new lava flows. In mid-2002, the crater, the upper rim of which was notched by erosion , was 180-200 meters in diameter. More cinder cones formed in the west of the mountain. In April 2002, lava flowed from the southeast side of the lava shields into the upper end of the Royal Gardens, where another abandoned house was buried. This "halp" stream continued to advance into the Royal Gardens until mid-June.

In the meantime, on May 12, 2002, a new eruption channel on the west side of the Puʻu ʻŌʻō spewed lava along the western edge of the river basin, triggering the largest forest fire in the national park in 15 years. The magma running off through this "Mother's Day" flow reduced the pressure below the Puʻu ʻŌʻō, so that the crater area and its surroundings calmed down. The "Halp" stream remained active with decreased activity through August.

The Mother's Day stream spilled into the sea near Chain of Craters Strait in July 2002. In the following year, lava flowed almost continuously into the sea in several places on the west side of the river basin. The longest lasting influence of this phase was in West Highcastle.

In the spring of 2003, lava streamed out of the Mother's Day tube again and spilled into the ocean on Valentine's Day , having previously absorbed another section of the Chain of Craters Street. This stream only remained active for two weeks. At the end of 2003, the events of late 2002 were repeated, so that the lower areas of the tube system again withered and the currents on the surface formed shield structures. Once again, cinder cones were active in the crater area, on its west side and the Puka Nui.

Increased crater and flank activity

In January 2004, lava flowed directly out of the crater for the first time since 1998 and flooded the West Gap and the eastern rim of the crater three times. A few days later, four new eruption channels opened on the south side of the Puʻu ʻŌʻō cone, causing a short but very active stream that was named Martin Luther Kings (MLK). As the process progressed, additional channels - known as MLK channels - opened and remained active until June 2005.

After the eruption of the MLK channels, the crater activity initially reduced, but began again in February 2004, with lava flowing for the first time directly from the Puʻu ʻŌʻō into the Puka Nui crater. More lava flows again flowed through the West Gap. The crater calmed down in early March and remained inactive until the end of the year. In March 2004, another larger eruption formed the Prince Kūhiō Kalanianaʻole tube (PKK) southwest of the cone , which became the dominant lava tube of the eruption from August. At the end of April 2004, the “banana” flow, which broke away from the lower edge of the lava shields, interrupted the eruptions of the Mother's Day flow, which slowly dried up from August. As of November 2004, the PKK tube was the only active lava tube. Their stream divided at the top of the Pali and formed two arms. The lava of the western arm first flowed into the sea in November 2004 at East Lae'apuki, that of the eastern arm only in January 2005. In June 2005 both currents flowed over a wide area of the coast - from Highcastle to Kailiili - into the ocean.

The activity of the eruption channels in and around the crater of the Puʻu ʻŌʻō increased again between January and February 2005 with an almost continuous leakage of lava within the crater. New cinder cones formed in craters, Puka Nui and the MLK channels. At the end of March, the cone collapsed on the most active eruption channel, so that a lava lake appeared by the end of the year. In May one of the MLK cones collapsed, exposing a lava lake measuring 10 × 15 meters, on the surface of which a crust had formed by the end of June. In the second half of the year, subsidence was the predominant change in the crater. From the PKK tube, lava reached the ocean 6 times during 2005 on more than 5 km of the coastline. At the end of the year only one stream was still active on the east side of Laeʻapuki, where the largest collapse to date (around 17.8 hectares) of a lava bank during the current eruption occurred on November 28th.

A quiet year

There were no particularly spectacular changes in 2006. Inside the crater, the relatively calm phase that began at the end of March 2005 continued and was mainly characterized by moderate subsidence.

The PKK tube fed a steady flow of lava into the ocean, where the inlet on the east side of Laeʻapuki remained active. In May, about a kilometer of the parted below the Pu'u'Ō'ō Campout stream from the PKK tube, reaching in August the ocean on the east side of Kailiili. Another arm of the Campout -stream reached in late December the coast at Kamokuna so that at the end of 2006, the lava flowed into the sea at three places. The current on the east side of Laeʻapuki was the longest active lava entry into the ocean with over 20 months and the lava bank formed by it also reached a record size of about 23 hectares.

The short break

After less and less lava was found in the area of the Puʻu ʻŌʻō in June 2007, the Hawaiian Volcano Observatory reported a break in the eruption from June 21 to July 1. From July 2nd to 14th, a lava lake was observed in the crater of Puʻu ʻŌʻō, and further activities at various locations followed. On July 21, fissure eruptions began east of the crater as far as Kūpaianaha.

Pāhoa in danger

On June 27, 2014, a lava flow began to flow, this time flowing in a northeastern direction. By the end of October he had covered a distance of more than 17 km. On October 26th, it broke off Apa'a Street and flowed through the Pāhoa cemetery a day later. On October 28th he reached the village, the first houses were about to be destroyed.

The lava flow from June 27, 2014 remained active until the beginning of June 2016 and especially in February and March there were again larger leaks of lava on the sides of the field.

Relocation of the lava flow towards the Pacific

After a short period from May 24, 2016 to the beginning of June, during which lava escaped both north and east, it became clear on June 10 that the lava flow from June 27, 2014 had become inactive and fresh lava was only in Towards the ocean, which was reached on July 26th in the area of the former beach Kamokuna .

On December 31, 2016, large parts of the unstable lava delta of Kamokuna collapsed .

Fissure eruption in Leilani Estates 2018

After increased earthquake activity since the end of April and the collapse of the crater floor in Pu'u 'Ō'ō on April 30 (local time), fissure eruptions began in Leilani Estates ( Puna district ) on May 3, 2018 (local time ). They were accompanied by other earthquakes, the strongest of which reached magnitude 6.9 - the most violent tremor on Hawaii since 1975 (7.1), when 2 people died. On May 3, 1700 people were officially ordered to leave the area. Another 10,000 residents of the Puna district were advised to leave as a precaution. In addition, the state of emergency was declared .

In connection with the earthquakes and the penetration of magma in the fracture zone, the Hawaiian Volcano Observatory published some facts according to which a feared catastrophic demolition along the Hilina Rift would be extremely unlikely. In the second half of May, the activity of the fissure eruptions increased, apparently after hotter magma from the Puʻu ʻŌʻō had reached the fissures. On May 19, some fissures merged and created lava fountains and several lava flows, some of which caused forest fires in the Malama Kī Forest Reserve , and the same evening after crossing the Hawaiʻi State Route 137 coastal road, the ocean in the Malama flats area not far from MacKenzie State Reached the Recreation Area . On May 22, it was reported that lava was also reaching the site of the Puna Geothermal Venture (PGV) geothermal power plant , which had been closed shortly after the crevasse erupted.

ʻAʻā lava from columns 16-20

Individual evidence

- ↑ Lt. Geographic Names Information System in the Geographic Names Information System of the United States Geological Survey 's Hawaiian spelling since 1999 by decision of the United States Board on Geographic Names (English) the official name

- ↑ cf. Google Scholar ; Ranulph Fiennes, Katharina Harde-Tinnefeld: Extremes of the earth . 2005, ISBN 9783936559316 , p. 212

- ↑ cf. Rita Ariyoshi: Hawaii . In: National geographic traveler , 7th, updated edition, 2013, ISBN 978-3-95559-022-2 ; Alfred Vollmer: Travel Know-How Hawaii: Travel guide for individual discovery. 10., rework. and compl. actual Edition, Bielefeld 2014, ISBN 978-3-8317-2449-9

- ↑ 7 months of no lava at Puʻu ʻŌʻō heralds end of an era (US Geological Survey Hawaiian Volcano Observatory, January 31, 2019); Preliminary summary of Kīlauea Volcano's 2018 lower East Rift Zone eruption and summit collapse (USGS)

- ↑ also mountain , the meaning of the Hawaiian word puʻu is broad, see puʻu in Hawaiian Dictionaries

- ↑ a b C. Heliker, DA Swanson, TJ Takahashi: "The Pu'u 'O'o Kupaianaha eruption of Kilauea Volcano, Hawaii: The First 20 Years" . In: US Geological Survey Professional Paper . 1676, 2003. Web link .

- ↑ Digging stick, digging implement, spade , see ʻōʻō (2.) in Hawaiian Dictionaries

- ↑ see pāoa in Hawaiian Dictionaries

- ^ WD Westervelt: Hawaiian Legends of Volcanoes . GH Ellis Press: Boston 1916. p. 6. cf. How Pele came to Hawaii

- ^ MO Garcia, JM Rhodes, FA Trusdell, AJ Pietruszka: "Petrology of lavas from the Puu Oo eruption of Kilauea Volcano: III. The Kupaianaha episode (1986-1992) ” . In: Bulletin of Volcanology . 58, No. 5, 1996, pp. 359-379. doi : 10.1007 / s004450050145 .

- ↑ US Geological Service: FAQs on the volcanoes on Hawaii ( Memento from February 3, 2017 in the Internet Archive ), measurement data from 1997/98.

- ↑ spatter and cinder cone , Photo glossary of volcano terms

- ↑ MLK Flow from January 18 to 24, 2004, cf. Tim R. Orr: Studies of Recent Eruptive Phenomena at Kīlauea Volcano . Ph.D. - Geology and Geophysics, University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa, 2015, http://hdl.handle.net/10125/51219 , pp. 9, 15.

- ↑ As Prince Kuhio Kalaniana'ole flow is called an active from March 2004 to June 2007 lava field; see. Christopher W. Hamilton, Lori S. Glaze, Mike R. James, and Stephen M. Baloga: Topographic and Stochastic Influences on Pāhoehoe Lava Lobe Emplacemen . In: Bulletin of Volcanology 75, No. 11 (November 2013), p. 2, https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Christopher_Hamilton2/publication/258237984_Topographic_and_stochastic_influences_on_pahoehoe_influences_on_pahoehoe_lobe_emplacement/linksinfluences-lava00/stonastic- 30000/stonastic- graphic- toch527 -pahoehoe-lava-lobe-emplacement.pdf .

- ↑ Lava Flow Threatens Pahoa, Hawaii . The Atlantic, October 28, 2014 (includes photo series from the outbreak)

- ↑ Angela Fritz: Hawaii lava flow advances, now less than 100 yards from nearest home in Pahoa . Washington Post, Oct. 28, 2014

- ^ Map from February 12, 2016

- ^ Map from March 25, 2016

- ↑ Map from May 24, 2016

- ↑ Map from June 2, 2016

- ↑ Map from June 10, 2016

- ↑ Kamokuna in the Geographic Names Information System of the United States Geological Survey

- ^ Map from July 26, 2016

- ↑ Map from January 3, 2017

- ^ Hawaiian Volcano Observatory Daily Update, US Geological Survey; Tuesday, May 1, 2018, 8:49 AM HST (Tuesday, May 1, 2018, 18:49 UTC) : USGS: Volcano Hazards Program - Hawaiian Volcano Observatory ( Memento of May 4, 2018 in the Internet Archive )

-

^ Leilani Estates

- ↑ Strongest vibration since 1975. orf.at, May 5, 2018, accessed May 5, 2018.

- ↑ Kilauea Volcano Erupts. USGS website, May 4, 2018 ff., Accessed May 6, 2018

- ↑ Hilina Slump , cf. Roger P. Denlinger, Julia K. Morgan: Characteristics of Hawaiian volcanoes (= Professional Paper 1801; https://pubs.usgs.gov/pp/1801/ ). US Geological Survey, 2014, ISSN 2330-7102 , Chapter 4: Instability of Hawaiian Volcanoes ( usgs.gov [PDF]).

- ↑ a b 'Laze' plume could carry toxic substances miles away from lava's ocean entry . 20th May 2018.

- ↑ cf. Map showing the location of the lava

- ↑ Hawaii power plant shut down as lava nears geothermal wells (May 22, 2018) ( Memento from May 23, 2018 in the Internet Archive )

Web links

Photos and videos

- Selected images of the Puʻu ʻŌʻō-Kūpaianaha eruption ( US Geological Survey )

- HVO: Pu'u 'Ō'ō webcams

Other

- US Geological Survey, Hawaiian Volcano Observatory - Kīlauea (English)

- Puʻu ʻŌʻō on fascination with volcanoes

- Card with lava 2018