Roman-Syrian War

The Roman-Syrian War (also Antiochus War or Syrian War ) was a military conflict during the years 192 to 188 BC. BC and was held in Greece , the Aegean and Asia Minor . There were two coalitions under the leadership of the Roman Empire on the one hand, the Syrian Seleucid Empire under Antiochus III. on the other hand, compared to the great.

The fighting went on since 196 BC. A "cold war" between the two great powers. During this period they endeavored to peacefully delimit their spheres of interest, but at the same time concluded alliances with regional central powers.

The military conflict ended with a clear victory for the Romans. In the Peace of Apamea , the Seleucids were born in 188 BC. Ousted from Asia Minor while their lost territories fell to Roman allies. The Roman Empire became through his victory over Antiochus III. became the only remaining great power in the Aegean region and from this point on exercised hegemony over Greece.

The Cold War"

Prehistory from 218 to 196 BC Chr.

Around 218 BC BC there were five great powers in the Mediterranean area , which were in a political balance: the Diadochian states of the Seleucids, Ptolemies and Antigonids ( Macedonia ) in the east and the city-states of Carthage and Rome in the west.

A series of conflicts changed this balance: On the one hand, in the Second Punic War (218 to 201 BC) the Romans fought with Carthage for supremacy in the western Mediterranean. Carthage lost the conflict, was confined to its African territories and sank to the status of a middle power. At the same time, Rome had to deal with Philip V of Macedonia, who had formed an alliance with Carthage, in the First Macedonian-Roman War (215 to 205 BC) . Philip was able to assert himself against a Roman-Greek coalition to which the Central Powers Aitolia , Pergamon and Rhodes also belonged, but from now on Rome was permanently involved in Greek politics.

In the "robbery contract" of 203 BC Philip and the Seleucid king Antiochus III agreed to meet. the division of the Ptolemy external possessions. Antiochus conquered the controversial Koile Syria in the Fifth Syrian War (202 to 198 BC) , while Philip initially took action against the Ptolemaic fortresses in the Aegean Sea. After these losses, the Ptolemy Empire was permanently weakened in foreign policy. As a result of his expansion, Philip V came into conflict with the Greek Central Powers, which now entered into a new alliance with Rome. In the Second Macedonian-Roman War (200 to 196 BC), in addition to the opponents of the previous war, Achaia also stood against Philip.

Since the other powers were bound in the war, Antiochus took advantage of the political situation and conquered in 197 BC. Large parts of Asia Minor. He also moved into areas of Philip in Caria and Lycia , which Philip had only recently won in the fight against the Ptolemy. In order to avoid a conflict with the Rhodians and their Roman allies, Antiochus ceded some cities to the island state. Nevertheless, he was able to expand his holdings considerably and gained an important naval base with Ephesus . Then Antiochus advanced to the Hellespont , where he again occupied cities that had previously been conquered by Philip. This suffered the decisive defeat against the Roman alliance in the Battle of Kynoskephalai , but delayed a peace agreement. Antiochus tried to create facts while Rome and her allies were still busy with Philip, and in the spring of 196 BC he continued. To Europe. There he conquered Thrace , had the dilapidated Lysimacheia expanded into the new regional capital with large funds and appointed his younger son Seleucus (IV) as viceroy.

The Roman commander, Titus Quinctius Flamininus , was unsure of Antiochus' other goals and made peace with Philip in the face of a possible new threat. Flamininus ended the Macedonian hegemony over Greece, but at the same time tried to establish a balance of power: Macedonia was therefore weakened by territorial losses, but remained as a counterpoint to the Aitolians and Achaeans and as a bulwark against the Dardans . In addition, Flamininus created several independent states such as Thessaly, which was previously controlled by Philip . In the summer of 196 BC Finally, during the Isthmian Games , Flamininus effectively proclaimed the freedom of all Greeks to the public.

At this point in time only two of the five great powers remained in the Mediterranean world: the Seleucid Empire and the Roman Empire.

Political goals of the Romans and Seleucids

The Seleucid Empire had gradually lost provinces since its foundation towards the end of the fourth century BC. Both internal uprisings and external opponents were responsible for this. As Antiochus III. in 223 BC BC ascended the throne, the empire was briefly limited to Syria . In the course of the next three decades he successfully opposed the process of decline and restored the Seleucid influence in Mesopotamia, Persia, central Asia Minor, Armenia, Parthia, Bactria and Koilesyria. Antiochus recognized in himself the restitutor orbis (restorer of the empire), who would regain all areas to which his ancestors had once claimed. He also believed he had a legal title with regard to Thrace, as several Seleucids had fought for this region in the past - most recently his uncle Antiochus Hierax in 226 BC. Chr.

Antiochus III. was sometimes deliberately superficial in its reconquest. He rarely set up direct administrations and left the defeated princes and cities their basic autonomy as long as they only recognized his nominal sovereignty and paid tributes. Antiochus avoided overt violence wherever possible, especially against the Greek cities of Asia Minor. According to his propaganda, he did not appear as a conqueror, but as a bringer of independence. In fact, the Seleucid rule meant partial internal autonomy for the cities. The price for this, however, was the loss of mobility in foreign policy, which contradicted the spirit of a classical Greek polis . In addition, domestic political self-determination also had its limits, since the cities had to provide troops and pay contributions in times of crisis. Through the Seleucid ruler's cult, the cities paid taxes to Antiochus, disguised as religious sacrifices.

The Roman Republic pursued a policy in Greece that was based on both utility and idealism. On the one hand it was the desire of the Romans to secure their eastern apron by fighting Philip. On the other hand, there was also a need to improve their moderate reputation in Greece through a just foreign policy. Flamininus tried to combine both aspects, since he considered the long-term policy to be promising that would also be in favor of the Greeks. Therefore he tried to install a multicentric and stable system by weakening the previous hegemonic power Macedonia and strengthening smaller states. The public proclamation of freedom for all Greeks in 196 was intended to give credibility to this policy and was reinforced in 194 by the withdrawal of the last Roman soldiers to Italy.

In fact, the new system of powers proved to be unstable, so that Rome ultimately had to decide in internal disputes and so gradually grew into the role of Greece's new hegemonic power. Antiochus' transition to Thrace in 196 complicated this situation, as the Romans feared that the Seleucid king would extend his influence to Greece. Rome therefore refused to formally recognize the Seleucid rule in Thrace. Two Greek cities in Asia Minor offered a suitable occasion to exert diplomatic pressure on Antiochus in return in Asia Minor: Smyrna and Lampsakos wanted to maintain their complete independence from the Seleucid Empire, which is why they asked Rome for support on the basis of its freedom policy. Alexandreia Troas later became the third city to oppose Antiochus.

Negotiations between the powers

Despite these discrepancies, neither of the two great powers wanted in 196 BC. The war. Conversely, however, they could not agree on a stable limit of interests. They tried to settle their differences at three conferences: In Lysimacheia (autumn 196) the Romans called on Antiochus to withdraw from Europe and free the Greek cities of Asia Minor. However, this referred to his supposed legal claim to Thrace and forbade any interference in his politics. At a conference in Rome (autumn 194) Flamininus made a realpolitical offer: If Antiochus withdrew from Thrace and accepted the Hellespont as a borderline of interests, the Romans would give him a free hand in Asia Minor. Since both sides refused to give in, in Ephesus (summer 193) they partly reverted to an idealistic argumentation. On the basis of their respective freedom propaganda, the Romans and Seleucids accused each other of suppressing the Greeks of Lower Italy or Asia Minor. Antiochus declared himself ready to forego some controversial cities of Asia Minor as the price for an agreement with Rome, but not to give up Thrace.

During this period a "Cold War" developed between Rome and Antiochus, during which they expanded their respective political positions in the Aegean region. One year after the peace with Macedonia, Flamininus had to fight to maintain order in Greece. As 195 BC When the Spartan ruler Nabis increased his sphere of influence at the expense of Achaia, Flamininus militarily forced him to return the disputed city of Argos and the naval base of Gytheion . However, Nabis himself was left in office because Flamininus wanted to maintain the balance among the Greek states.

In the war against Nabis, the Romans had been supported by almost all of the Greek Central Powers with the exception of the Aitolians. Since the war against Philip they had won, they had become opponents of Rome because they had hoped for great territorial gains in Thessaly, but Flamininus had not wanted to allow any significant expansion of the existing powers. Therefore, in the winter of 195/194 BC, the Aitolians took Chr. Contact to Antiochus in order to move this to an action against the Romans. The Seleucid king was not averse, but still hoped for a consensus with Rome. However, he secured from against a possible war on two fronts against Rome and Egypt by one of his daughters with Ptolemy V married. Otherwise Antiochus limited himself in the years 196 to 194 to fighting against the Thracian tribes in order to secure this province permanently, as well as a 193 campaign to Pisidia .

From 194 BC The later war coalitions were already formed: while Aitolia was drawing closer to the Seleucid king, Macedonia, Achaia, Pergamon and Rhodes sided with Rome. Philip of Macedonia was given hopes by the Roman side that the strict peace conditions could be relaxed. In addition, both Antiochus and the Aitolians had become a threat to Philip through his conquest of Thrace. The Achaians speculated on the unification of the Peloponnese with Roman help. King Eumenes II of Pergamon was enclosed on three sides by Seleucid territory in Asia Minor after his father had lost large areas to Antiochus and previously his viceroy Achaios . Since Eumenes did not want to be satisfied with the role of a Seleucid sub-king, he turned down the offer of marriage to one of Antiochus' daughters and built on the alliance with Rome. The Rhodians had worked with Antiochus for a short time, but could only enlarge their national territory at the expense of the Seleucid Empire.

Aitolia's policy against the Roman order

Although the Romans and Seleucids did not press for an armed confrontation directly during the Cold War, they were also unable to regulate their political relationship by treaty. This became critical at the moment when several local conflicts broke out in Greece, which provoked the intervention of both great powers.

Because of the superior military power of Rome, the Aitolians could only hope for an expansion of their own power in league with Antiochus. They had therefore invited the Seleucid king to land in Greece and re-regulate the balance of power. However, since this did not react immediately, the Aitolians provoked a situation in which Rome would be forced to invade Greece again. The latter would ultimately have given Antiochus the choice of permanently accepting Rome's hegemony in Greece or supporting the Aitolians, his only allies.

In the spring and summer of 192 the Aitolians attempted to bring about political upheavals in three important Greek cities in order to provoke the intervention of both great powers: Demetrias was, along with Chalkis and Corinth, one of the three “shackles” from which Macedonia had ruled Greece for decades. In the recently autonomous city there was unrest, as it was feared that Rome would return the city to Philip. Flamininus went to Demetrias to ease the situation, where the city's magnetarch accused him of an imperialist policy. Flamininus reacted so furiously that he fled to Aitolia and the councilors of Demetrias set up a pro-Roman government to appease them. After Flamininus' departure, however, the Magnetarch was led back to Demetrias by Aetolian troops, where they forcibly took control.

A similar attempt to take power in Chalkis, another former fetter, on Euboia failed, however. Aetolian soldiers tried to penetrate the city with the support of Chalcidian exiles in order to overthrow the pro-Roman city government. The latter called the friendly cities of Eretria and Karystos for help and was able to assert itself militarily against the Aitolians.

The Aitolians tried in the summer of 192 to win Sparta for an alliance against Rome. Nabis initially agreed and had the Achaean port of Gytheion reoccupied, but after Roman mediation agreed to a renewed armistice, after which the political situation calmed down again. This was not in the spirit of the Aitolians, who could only overturn Flamininus' order through a major war. An Aetolian contingent marched to Sparta under the pretext of wanting to support Nabis militarily, but murdered him during a joint maneuver. However, the Aitolians did not succeed in seizing control of the city, as Nabis' supporters appointed a young family member of the murdered man as the nominal successor. Ultimately, only the Achaeans benefited from Nabis' death, as Sparta soon joined their state.

Outbreak of war

Only the Aitol overthrow in Demetrias was successful, but this was enough to provoke the desired intervention of both great powers: Rome was by no means ready to accept Demetrias' defection, which is why the envoy Publius Villius Tappulus threatened the city with consequences. However, it was to be expected that another Roman intervention would not be limited to Demetrias, but would primarily be directed against the Aitolians. However, an Aetolian defeat against the Romans would also have had an impact on Antiochus: Should Rome no longer have to take into account oppositional forces in Greece, the position of the Seleucid king in Asia Minor and Thrace would have become uncertain. Despite inadequate preparations, Antiochus therefore began the invasion of Greece in the autumn of 192.

The possibility of waging war against Rome had already been discussed at the Seleucid court during the Cold War. One of the spokesmen was the former Carthaginian general Hannibal . Rome's great opponent from the Second Punic War persisted since 195 BC. In the Seleucid Empire after he had to leave his hometown at the instigation of his domestic political opponents. Hannibal recommended to Antiochus that in the event of a war he would absolutely have to tie up Rome's resources in Italy: While the king and his army were invading Greece, Hannibal would seize power with a Seleucid fleet in Carthage and then invade Italy. However, Hannibal's plan was rejected by Antiochus, as he himself wanted to lead the main attack in his function as army king. Nonetheless, Antiochus originally planned a weakened enterprise under Hannibal's command: He was supposed to at least take over power in Carthage with a small fleet, which would have politically bound Rome, as it would have had to leave troops behind in southern Italy in the face of a hostile Carthage. However, when the situation in Demetrias came to a head, Antiochus rejected this plan and used the units planned for Hannibal as part of his own invasion forces for Greece.

Antiochus decided to intervene in Greece at short notice, so that his armed force was relatively small with 10,000 infantry, 500 cavalry and six elephants . The Romans were much better prepared for an intervention in the Aegean region than the Seleucid king: preparations for a military operation in Greece had already been made since the Aitol overthrow in Demetrias in the spring. An army of 25,000 men, which had originally served to protect against a possible invasion by Hannibal or even Antiochus himself, crossed over to Apollonia . In addition, another 40,000 men were dug in Italy and the fleet in Brundisium was enlarged.

Course of war

Antiochus' landing in Greece

Antiochus landed with his army in Demetrias, whose councilors, who were mostly hostile to Rome, received him kindly. The alliance between the Seleucids and Aitolians was publicly affirmed in Lamia , when Antiochus was chosen as the nominal strategist of the covenant.

The Seleucid king then tried to win Chalkis over to his cause, but the city turned down his offer of an alliance. Antiochus then sent 3,000 men under the leadership of Menippus with the fleet to Chalkis and followed himself with the rest of the army. At the same time, 500 Roman and 500 Achaean soldiers marched in support of the city. The Achaeans were able to reach the city in time, but Menippus arrived before the Romans and occupied the fortress belonging to Chalkis on the other side of the Euripos Canal. The Romans then procured transport boats to cross over to another point on the island of Euboia. Menippus, however, did not allow the Chalcidians to be reinforced and attacked the relief forces near the Temple of Delion . Most of the numerically inferior Romans were killed or taken prisoner, while the rest escaped to Chalkis. When Antiochus later arrived with the rest of the Seleucid army, Chalkis surrendered after the Roman-Achaean auxiliary troops and the pro-Roman politicians had been allowed to withdraw.

Despite this success, the Greek states remained reserved about Antiochus. Only King Amynandros of Athamania was willing to actively participate in the war, as he wanted to install his brother-in-law as the Macedonian king. Some smaller powers strived for at least a good relationship with the Seleucids: Boeotia and Epeirus formally entered into alliances with Antiochus, but remained factually neutral. Elis received 1,000 Seleucid soldiers to support them in order to maintain a counterweight to the Achaeans in the Peloponnese.

The Seleucid-Aitolian alliance invaded Thessaly in the winter of 192/191. Its inhabitants were hostile to Antiochus, as they owed their independence to Rome. The Seleucid king was able to bring most of Thessaly under his control , except for the city of Larissa , when bad weather forced him to return to Chalkis. However, he had to leave strong occupation troops behind to control the landscape, which is why the Seleucid fleet was sent back to Asia Minor to fetch supplies. To show his attachment to Greece, Antiochus married a Chalkidian woman.

The battle of Thermopylae

The praetor Marcus Baebius Tamphilus with his 25,000 soldiers from Apollonia from Thessaly could not reach in time and set up his winter camp in Macedonia. In the meantime, King Philip had entered the war openly in favor of Rome, whereupon he received permission to increase his army, which was limited to 5,000 men by contract. In the spring of 191, Tamphilus and Philip began to recapture Thessaly separately. The northeast fell quickly to Tamphilus as there were few Seleucid garrisons there. In the west of Thessaly, however, Philip met the resistance of the Athamanians, who entrenched themselves mainly in the city of Pelinna. Only when Tamphilus' troops and another 12,000 Romans arrived as reinforcements under the consul Manius Acilius Glabrio , the city capitulated. Philip then marched into Athamania without further difficulties, whereupon King Amynandros fled into exile in Ambrakia . Glabrio took over the supreme command of the Roman army and turned against southern Thessaly, where there were still some stronger Seleucid garrisons. However, these arose after they were allowed to withdraw through Macedonian territory. With this, the Roman and Macedonian troops controlled northern Greece.

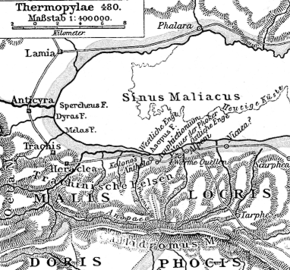

Antiochus had tried to win Akarnania while the Romans were busy in northern Greece. Although the city of Medeon joined him there , most of the Akarnans opposed him because of their traditional rivalry with the Aitolians. Antiochus finally gave up Akarnania and hurried back to Chalkis to gather his troops for a field battle against the Romans. Since reinforcements had arrived from Asia Minor in the meantime, the Seleucid king again had 10,000 soldiers, as at the beginning of the campaign. His Aitolian allies could have raised the same number at most, but they only sent 4,000 men to support them because they feared an attack on their own territory by Philip. Due to his numerical inferiority, Antiochus decided against an open field battle and took position at the eastern gate of Thermopylae . Half of the Aitolians were stationed in the city of Herakleia at the western gate of the narrows, while the rest took over the guarding of the mountain passes.

Glabrio advanced with about 30,000 men from Thessaly. He first had the area around Herakleia devastated in order to provoke a failure of the Aitolians, but they stayed in the city. Despite the enemy behind him, Glabrio advanced into Thermopylae. He sent two contingents of 2,000 men each, who were supposed to overcome the mountain passes and stab the Seleucid army in the rear. Although Antiochus had fortified the narrowness, Glabrio dared the so-called Second Battle of Thermopylae and launched a frontal attack. Due to their favorable strategic position, the Seleucids were initially able to hold on despite being outnumbered. However, one of the two Roman contingents broke through under the orders of Marcus Porcius Cato against the resistance of the Aitolians at the pass. Cato was now able to attack the Seleucids on the flank, whereupon they began a disorderly retreat. Antiochus escaped with part of the army to Chalkis, but many of his soldiers were taken prisoner by the Romans. His remaining troops in Greece comprised several thousand men, but they were stationed far apart, so that the Seleucid king retreated to Asia Minor.

Sea War I: Korykos

Despite Antiochus' flight, the war in Greece was not over from the Roman point of view, as the Aitolians continued the fight thanks to Seleucid subsidies . Glabrio had succeeded in taking the Aetolian fortresses of Herakleia and Lamia, but Naupaktos and Amphissa remained undefeated. The central theater of war now shifted to the Aegean. The Romans needed sea sovereignty for a counter-invasion in Asia Minor, which Antiochus tried to prevent.

The Seleucid Admiral Polyxenidas, a native of Rhodians, had 200 ships, but only 70 of them were large tectae , while the rest were smaller apertae (covered or open ships). Two factors made his task more difficult: On the one hand, the Seleucids as a land power lacked maritime experience, on the other hand the Romans were supported at sea by Pergamon and Rhodes.

The Roman fleet was under the command of the Praetor Gaius Livius Salinator . This was subordinate to a fleet of 81 Quinqueremen and 24 smaller units. Salinator's first war goal was to unite with the powerful fleets of his allies in order to outnumber his rival. First he sailed towards Pergamon. Polyxenidas therefore anchored in Phocaea, not far away, but could not prevent the rendezvous between the Romans and the Pergameners. He then withdrew into the strait between the island of Chios and the Erythraic Peninsula in order to stay near his naval base Ephesus and from there to prevent at least the union between Salinator and the Rhodian ships.

Thanks to Eumenes' units, Salinator now had 105 large tectae and 50 small apertae . In the autumn of 191 he turned south to include the Rhodian ships in his armada. In the coastal waters off Korykos , Polyxenidas tried to prevent the Roman-Pergamene fleet from breaking through. However, after his ships were outflanked on the seaside, he had to retreat to Ephesus, with 23 ships being lost. After the arrival of the Rhodian fleet, Salinator had a clear advantage over Polyxenidas with a total of 130 tectae . However, the Roman praetor soon left his position in front of Ephesus and divided up his armada again. While the Rhodians were supposed to secure their own waters, Salinator sailed north with the Roman and Pergamene ships to gain control of the Hellespont.

Sea War II: Myonessos

Despite the defeat at Korykos, Antiochus did not give up the naval war. During the winter of 191/190, on the one hand, Polyxenidas was commissioned to reinforce his battered fleet in Ephesus with new large ships. On the other hand, Hannibal was supposed to pull together a second fleet in Syria and Phenicia and sail with it into the Aegean Sea. After Polyxenidas had brought his fleet strength back to 70 tectae in the spring of 190 , he sailed south to defeat the Rhodian fleet under Pausistratos and thus clear the way for a later union with Hannibal's ships. In a combined land-sea operation, Polyxenidas locked 36 enemy ships in the port of Panormos on the island of Samos and destroyed all but seven of them.

Salinator had unsuccessfully besieged Abydos , which was the most important Seleucid base on the bank of the Hellespont in Asia Minor. When he heard of Polyxenidas' victory at Panormos, Salinator sailed south, whereupon the Seleucid fleet withdrew again to Ephesus. Polyxenidas now had 90 units thanks to numerous conquered Rhodian ships, but was still outnumbered as the Rhodians sent new ships, whereby the fleet of the Roman coalition grew again to 120 tectae .

Salinator's command now fell to the new Praetor Lucius Aemilius Regillus . This first made some unsuccessful attacks on Seleucid bases in Caria and Lycia. Since Regillus had to gain control of the Hellespont, but at the same time wanted to keep Polyxenidas in Ephesus, King Eumenes was sent to the strait with the Pergamene squadron.

Polyxenidas' hope was directed primarily at the union with the approaching second fleet under Hannibal. However, this would first have to break through the Rhodian lines. At Side , however, Hannibal's 47 ships met a Rhodian fleet of 38 units under the command of the Eudamos. While Hannibal's stronger wing was blocked by a few opponents, the Rhodians won a clear victory on the second wing, whereupon the Seleucid fleet had to retreat and did not venture any further advance.

Due to the failure of Hannibal, Polyxenidas was forced to act and dared the decisive naval battle against Regillus. The two fleets met at Myonessos in the summer of 190. Polyxenidas were under 89 ships, while Regillus only had 70, as he had to do without the Pergamener and was only supported by a Rhodian squadron. The battle started unfavorably for the Romans, as their ships on the sea wing threatened to be surrounded by the Seleucid fleet. Thereupon, however, the fast Rhodian ships came to their aid from the land wing, while the more immobile units of their opponents could not follow this maneuver. Polyxenidas lost 42 of his ships and withdrew to Ephesus. The naval war had thus been decided in favor of Rome and the passage of the Roman army over the Hellespont secured.

The Battle of Magnesia

The command of the Roman army in Greece had meanwhile passed from Glabrio to the new consul Lucius Cornelius Scipio , who had received 13,500 men as reinforcements. He was accompanied as a legate by his better-known brother Publius Cornelius Scipio Africanus . The latter managed to negotiate a six-month armistice with the Aitolians, which allowed the Romans to march to Asia Minor. After the Roman victory at sea, Regillus was able to occupy the Hellespont with his fleet without further difficulties. Antiochus prepared for a battle inland and therefore surrendered the coastal cities on both sides of the strait without a fight. The Roman army under Lucius Scipio finally reached the abandoned Lysimacheia in November 190 and crossed to Asia Minor.

In view of the unfavorable course of the war, Antiochus sought an alliance with Bithynia , which, however, insisted on its neutrality. The Ptolemies offered the other side their entry into the war against Antiochus. However, Rome refused because it did not want the conflict to expand. Antiochus had already unsuccessfully asked for peace negotiations during the naval war and was now making a new attempt. He offered the Romans to give up Thrace and all disputed cities in western Asia Minor and to pay for half of the Roman war costs. Scipio Africanus, however, demanded the abandonment of the whole of Asia Minor up to the Tauros and the reimbursement of the entire war costs - roughly the conditions that were actually laid down in the later peace agreement. The Seleucid king did not accept this and took up position with his army near Magnesia , from where he could secure both the way to Sardis and Ephesus.

The Romans advanced south and met the Seleucid army in the Battle of Magnesia in December 190 . Lucius Scipio had about 50,000 men under his command, mostly heavy infantry from Rome or Italy. In addition, there were smaller contingents of the Greek allies, the Pergamene cavalry being the most important. Antiochus had about the same number of warriors available, although his army was structured much more heterogeneously and was composed of soldiers from all parts of the empire. The battle began favorably for Antiochus, who at the head of his cavalry overran the left wing of the Romans. At the same time, however, King Eumenes prevailed with his cavalry on the right wing and was able to attack the Seleucid phalanx from the side. An elephant attack on the Roman infantry had no effect. After considerable fire, the animals panicked and went against their own ranks. As a result, the already weakened phalanx collapsed and the Seleucid troops fled.

Rome's fight against Aitolians and Galatians

After the lost battle, Antiochus gathered his remaining troops in Apamea . Soon afterwards he asked the Romans for an armistice, which he was granted in return for the payment of 500 talents and the placement of 20 hostages. Militarily, the war was now decided, which both sides recognized in fact, so that there was no further fighting between the Romans and the Seleucids. Nevertheless, it was still more than a year after the Battle of Magnesia before both parties concluded peace in the spring of 188 after long negotiations.

Around the same time as the Battle of Magnesia, the war in Greece flared up again briefly. After Lucius Scipio's army withdrew in December 190 and the armistice had expired, the Aetolian League started a new offensive. Philip of Macedonia had previously taken Athamania and several Aetolian border towns, but was now repulsed by the Aitolians. Furthermore, they reinstated Amynandros as the Athenian king. In the spring of 189, however, the new consul Marcus Fulvius Nobilior landed in Greece with 35,000 soldiers, and the Seleucid defeat became known. In view of their hopeless situation, the Aitolians began peace talks with Rome. Nobilior therefore limited himself during the negotiations to the siege of the city of Ambrakia and the conquest of the island of Kephallenia , which belonged to the Aitolian League and which he annexed for Rome.

Most of the major cities in western Asia Minor went over to the Romans in the winter of 190/189, including Ephesus and the regional capital Sardis, where Lucius Scipio set up his winter camp. In the spring he was replaced by the new consul Gnaeus Manlius Vulso , who, due to the unambiguous Roman victory, did not bring any reinforcements with him. Vulso respected the armistice and avoided all Seleucid garrison towns that had not yet been given up, but took massive action against the Galatians . This campaign served not only to steal loot, but also had a propagandistic meaning: up to that point, protection against the Galatians had been the task of the Hellenistic kings, whose function was now transferred to Rome. During these battles, Vulso's army was partially supplied by the Seleucids, who had come to terms with the situation.

In the summer of 189 the official peace conference was finally opened in Rome. Its outcome, however, had already been determined in the main and largely corresponded to the conditions that had been offered to Antiochus by Scipio Africanus before the battle of Magnesia. However, the king himself did not take part in the conference, but was represented by Zeuxis , the former viceroy of Asia Minor. In addition to the Seleucid ambassadors, King Eumenes as well as the Rhodians and representatives of the Allied cities took part in the negotiations. Zeuxis' diplomatic options were few in view of the clear course of the war, so that he could get only a few perks. In the spring of 188 BC Finally the peace between the Roman Empire and the Seleucid Empire came into force.

The Peace of Apamea

Content provisions

The Peace of Apamea brought enormous political changes with it: Antiochus had to cede Thrace and Asia Minor to the Tauros Mountains. Only Cilicia , which borders directly on Syria, remained in his possession up to the Kalykadnos River . With this radical regulation, Rome permanently pushed back the Seleucid influence in the Aegean region. Antiochus was also forbidden from any foreign policy interference in Asia Minor to the detriment of the Roman allies.

The immediate winners of this arrangement were Pergamon and Rhodes. Rome itself did not want to establish direct rule in Greece and Asia Minor and therefore left all territorial gains to its allies - with the exception of the previously Aetolian and Athamanian islands of Kephallenia and Zakynthos . With Lysimacheia , Chersonese , Mysia , Lydia , Phrygia , Pisidia and northern Caria, King Eumenes received the lion's share of the former Seleucid possessions. The Rhodians had to be content with Lycia and southern Caria. Those cities that had allied themselves with Rome before or during the war, however, remained independent, as Rome had fought the war ostensibly for their autonomy.

The Seleucid Empire was obliged to pay Rome a total of 15,000 talents of silver. Antiochus had already had to hand over 500 at the armistice, to which a further 2,500 were added at the peace agreement. The remaining money was paid in installments of 1,000 talents over the next twelve years. This meant that the Seleucids had to pay 50 percent more reparations in a quarter of the time than Carthage a few years earlier after the Second Punic War. This was a considerable burden even for the financially relatively strong Seleucid Empire.

Rome stipulated further conditions that should make it difficult for the Seleucids to return to the Aegean region: Antiochus' fleet was limited to ten ships, which, moreover, were only allowed to sail as far as Cape Sarpedon, located behind the mouth of the Kalykadnos. The possession of war elephants was forbidden, but the Seleucids only adhered to this for a few years. Furthermore, it was forbidden that the Seleucid kings were allowed to hire Galatian mercenaries from Asia Minor as before.

An unpleasant demand that would have endangered his reputation, however, remained without consequences for Antiochus: the Romans insisted on the extradition of some prominent opponents of the Roman order. These escaped through suicide or, like Hannibal, through flight, while others were granted pardon. However, the youngest son of the Seleucid king , who later became Antiochus IV , had to go to Rome as a hostage.

Political consequences for the Aegean region

The Roman-Syrian War changed the political power constellation in the Mediterranean considerably. The Greek historian Polybios believed in the period from 218 to 146 BC. To recognize a political process that resulted in the emergence of the Roman Empire. The war against Antiochus marked the end of the first phase in which Rome successively defeated the great powers Carthage, Macedonia and Syria (the Seleucid Empire).

To be able to win these disputes, Rome needed allies and had to take their interests into account. Therefore, until 188 BC. The wars in Greece were waged in agreement with the regional central powers. Rome did not yet exercise direct rule over the Greeks, but tried to create a balance between their states. This policy was primarily due to Flamininus. On the one hand, this was intended to ensure that no new Greek hegemonic power would emerge, which could then become dangerous for Rome, as Philip V had been. On the other hand, major external powers should not find allies in Greece as they did during the Second Punic War. In order for this foreign policy system to remain stable in Greece, Rome had to keep the Greek Central Powers small on the one hand and prevent major external powers from intervening on the other. After the defeat of Antiochus in 188 BC The second point had become obsolete because Rome had become the hegemon over the Aegean region.

The Roman Republic did not yet rule Greece directly. However, it was now the only remaining great power called on as an arbitrator in every conflict within Greece. Rome eventually moved away from its policy of a Greek balance and increasingly encouraged pro-Roman forces. This new attitude towards the Greeks was cynically called nova sapientia (new wisdom). However, this policy was only possible because, after the great Hellenistic monarchies had been contained, Rome no longer had to take into account states of equal standing. With the end of the Macedonian kingdom in 168 BC After the Third Macedonian-Roman War and the establishment of the province of Macedonia in 146 BC. BC Rome finally went over to direct rule in Greece.

Consequences for the warring parties

The Aetolian League was the only notable opponent of Rome within Greece during the Roman-Syrian War. Since the Romans in 188 BC Chr. Promoted a political balance, the Aitolians were only punished with relatively small reparations and territorial cedings. In contrast, Rome's allies in the war against Antiochus were able to achieve significant gains in the short term: Pergamon and Rhodes controlled large areas on paper. Philip of Macedon made up at least part of his losses from the previous war against Rome. The Achaean League finally completed its long-sought unification of the Peloponnese. In the long term, however, these Central Powers had lost their flexibility in foreign policy because they had become part of a unilateral system of powers . Rome's victory over the rival great powers marked the beginning of the end of Greek independence.

Even in the run-up to the Roman-Syrian War, Rome's internal political power structure changed. Since the defeat of Cannae in 216 BC The important families around Scipio and Flamininus had been able to gain more influence on Roman politics than had previously been the case within the senatorial body. The faction around Cato opposed this development, among other things, by ensuring that no more commands were extended during the fight against Antiochus. Scipio Africanus achieved a final political success as the legacy of his brother - who was given the honorary title Asiaticus in honor of his victory at Magnesia . One year after the end of the war, both brothers' political careers were brought to an end after a lawsuit for alleged corruption. With this, Cato's faction, which did not want to accept any politicians who had been removed from the other senators, had achieved its goal.

The Seleucid Empire suffered heavy losses in the peace of Apamea. With regard to the Mediterranean, it had sunk to a middle power and no longer dared to rebel against Rome's will. This was especially true in 168 BC. BC on the " Day of Eleusis ", when Antiochus IV gave up his conquest of Egypt on a diplomatic initiative from Rome. In contrast to the Greek Central Powers, however, the Seleucid Empire retained its autonomy within the imperial borders. In the Middle East it remained the most important great power for another two generations, until internal power struggles and the rise of the Parthians caused its decline. Antiochus III. The great one, however, had to experience firsthand the consequences of his defeat against Rome: When attempting to collect an extraordinary temple tax in order to be able to pay the reparations for Rome, he was killed in 187 BC. Killed in Iran.

literature

swell

The Roman-Syrian War can be reconstructed primarily through the treatises of the ancient historians Polybius and Livy and, to a lesser extent, through the writings of Appian . However, all three describe the conflict primarily from a Roman point of view, so that their representations are in part tendentious.

The Achaean Polybios experienced the war as a child, at least from afar. Its depiction is closest to the events in terms of time and also has the greatest claim to objectivity, but has only been handed down with gaps. Polybius was interested in the Roman-Syrian War, among other things, as his primary goal was to depict the rise of Rome to become the only great power in the Mediterranean.

Livy and Appian both refer to Polybios. The Roman historian Livy, a contemporary of Augustus, describes both the war and its prehistory in detail, but evaluates some events in part in favor of the Romans. Through Appian, who lived at the time of the adoptive emperor , several facts of Polybius are passed down that do not occur in Livy.

- Polybios : Historíai , book 18-21 (where book 19 has not been preserved), in: Walter Rüegg (ed.), Polybios. History: Complete edition in two volumes , Zurich 1961/1963.

- Titus Livius : Ab urbe condita libri , book 33–38, in: Hans-Jürgen Hiller (ed.), Roman history: Latin and German. T. Livius , Munich 1982.

- Appianos of Alexandria: Syriaka , in: Kai Brodersen (Ed.), Appians Abriss der Seleukidengeschichte , Munich 1989.

Secondary literature

- Ernst Badian : Rome and Antiochus the Great. A Study in Cold War . In: Classical Philology . tape 54 , 1959, pp. 81-99 .

- Bezalel Bar-Kochva: The Seleucid Army. Organization and Tactics in the Great Campaigns . Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1976, ISBN 0-521-20667-7 .

- Boris Dreyer : The Roman rule of nobility and Antiochus III . Marthe Clauss, Hennef 2007, ISBN 978-3-934040-09-0 .

- Robert Malcolm Errington : Rome against Philip and Antiochus . In: AE Astin (Ed.): Cambridge Ancient History . 1989, p. 244-289 .

- Hans-Joachim Gehrke : History of Hellenism . 4th edition. Oldenbourg, Munich 2008, ISBN 978-3-486-58785-2 .

- John D. Grainger: The Roman War of Antiochus the Great . Brill, Leiden and Boston 2002, ISBN 90-04-12840-9 .

- Erich Stephen Gruen: The Hellenistic World and the Coming of Rome . University of California Press, Berkeley 1984, ISBN 0-520-04569-6 .

- Andreas Mehl : On the diplomatic relations between Antiochus III. and Rome 200-193 BC Chr . In: Christoph Börker, Michael Dondere (Ed.): Ancient Rome and the East. Festschrift for Klaus Parlasca on his 65th birthday . Erlangen 1990, p. 143-155 .

- Hatto H. Schmitt : Investigations into the history of Antiochus the great and his time . Steiner, Wiesbaden 1964.

Individual evidence

- ^ A b Ernst Badian: Rome and Antiochos the Great. A Study in Cold War . In: Classical Philology . tape 54 , 1959, pp. 81-99 .

- ↑ On the Seleucid-Rhodian relationship cf. H. Rawlings III: Antiochos the Great and Rhodes , in: American Journal of Ancient History 1 (1976), pp. 2-28.

- ↑ See Ernst Badian, Rome and Antiochos the Great. A Study in Cold War , in: Classical Philology 54 (1959), p. 87.

- ↑ Livy, Ab urbe condita libri 33, 38; Appian, Syriaka 1. On the possible function of Lysimacheias: F. Piejko, The Treaty between Antiochus III and Lysimachia approx. 196 BC , in: Historia 37, 1988, pp. 151-165.

- ↑ On the role of Macedonia in Flamininus' concept cf. Frank William Walbank, Philip of Macedon , Cambridge 1967, p. 174.

- ↑ Polybios, Historíai 18, 46; Livy, Ab urbe condita libri 33, 32.

- ↑ Hatto H. Schmitt, Investigations on the History of Antiochus the Great and His Time , Wiesbaden 1964, pp. 85–87.

- ↑ On the Seleucid tradition in Thrace: John D. Grainger, Antiochus III in Thrace , in: Historia 15, pp. 329–343.

- ↑ Boris Dreyer, Die Roman Nobilitätsherrschaft und Antiochos III , Hennef 2007, p. 317.

- ↑ Boris Dreyer, The Roman Nobility Authority and Antiochus III , Hennef 2007, p. 161.

- ↑ See Erich S. Gruen, The Hellenistic World and the Coming of Rome , Berkeley 1984, p. 146.

- ^ Ernst Badian: Rome and Antiochus the Great. A Study in Cold War . In: Classical Philology . tape 54 , 1959, pp. 85 .

- ↑ See Robert M. Errington, Rome against Philipp and Antiochos , in: AE Astin (Ed.), Cambridge Ancient History , Volume VIII (1989), p. 276.

- ↑ Polybios, Historíai 18, 51; Livy, Ab urbe condita libri 33, 40; Appian, Syriaka 6.

- ↑ Livius, Ab urbe condita libri 34, pp. 57–59.

- ^ Livy, Ab urbe condita libri 35, 15-16.

- ↑ Appian, Syriaka 12.

- ^ Appian, Syriaka 5.

- ↑ Livy, Ab urbe condita libri 35, 31–34.

- ^ Livy, Ab urbe condita libri 35, 37-39.

- ^ Livy, Ab urbe condita libri 35, 35-36.

- ^ Livy, Ab urbe condita libri 35, 39.

- ^ Robert M. Errington, Rome against Philipp and Antiochos , in: AE Astin (ed.), Cambridge Ancient History , Volume VIII (1989), p. 280.

- ↑ Livy, Ab urbe condita libri 34, 60; Appian, Syriaka 7. On the Hannibal Plan cf. Boris Dreyer, Die Roman Nobilitätsherrschaft and Antiochos III , Hennef 2007, pp. 223–228.

- ↑ Livy, Ab urbe condita libri 35, 42.

- ↑ Livy, Ab urbe condita libri 35, 43.

- ^ Livy, Ab urbe condita libri 35, 20–24.

- ↑ Livy, Ab urbe condita libri 35, 41.

- ^ Livy, Ab urbe condita libri 35, 46.

- ↑ Livius, Ab urbe condita libri 35, 50–51; Appian, Syriaka 12.

- ↑ Livy, Ab urbe condita libri 35, 47; Appian, Syriaka 13: This was Philip of Megalopolis.

- ↑ Livy, Ab urbe condita libri 35, 47 and 36, 5-6.

- ^ Livy, Ab urbe condita libri 36, 8-10.

- ↑ Livy, Ab urbe condita libri 36, 11 and Appian, Syriaka 16 claim that the king would have become politically inactive as a result of his marriage to the much younger Euboia. However, this is doubted by John D. Grainger, The Roman War of Antiochos the Great , Leiden and Boston 2002, p. 220, since, according to these two chroniclers, Antiochus was very active both militarily and diplomatically during the winter.

- ↑ Livy, Ab urbe condita libri 36, 13-14.

- ^ Livy, Ab urbe condita libri 35, 12.

- ^ Livy, Ab urbe condita libri 36, 15; Appian, Syriaka 17.

- ^ Livius, Ab urbe condita libri 36, 16-19; Appian, Syriaka 18-19.

- ^ Livy, Ab urbe condita libri 36, 22–30.

- ^ Livy, Ab urbe condita libri 36, 42.

- ↑ Livy, Ab urbe condita libri 36, 44–45; Appian, Syriaka 22.

- ^ Livy, Ab urbe condita libri 37, 8.

- ↑ Livy, Ab urbe condita libri 37, 10–11; Appian, Syriaka 24.

- ^ Livy, Ab urbe condita libri 37, 16-17.

- ^ Livy, Ab urbe condita libri 37, 23–24.

- ^ Livy, Ab urbe condita libri 37, 27–30; Appian, Syriaka 27.

- ^ Livy, Ab urbe condita libri 37, 6.

- ↑ Polybios, Historíai 21, 4-5; Livy, Ab urbe condita libri 37, 7.

- ↑ Livy, Ab urbe condita libri 37, 25.

- ↑ Cf. John D. Grainger, The Roman War of Antiochos the Great , Leiden and Boston 2002, p. 363: After Hannibal's ships left, a Ptolemy fleet plundered the Seleucid port city of Arados , but left it with this one attack.

- ↑ Polybios, Historíai 21, 13-15; Livy, Ab urbe condita libri 37, 35; Appian, Syriaka 29.

- ↑ Livius, Ab urbe condita libri 37, 37–43; Appian, Syriaka 30–35: According to Appian, Lucius Scipio was in fact represented in the high command by Gnaeus Domitius Ahenobarbus , which, however, would have contradicted Roman tradition.

- ↑ Just like Appian, Syriaka 31, Livius, Ab urbe condita libri 37, 39 gives only 30,000 men for the Roman side, but this contradicts the information he made about the individual Roman contingents that reached Greece in the course of the war : John D. Grainger, The Roman War of Antiochos the Great , Leiden and Boston 2002, p. 321.

- ↑ With Livius 60,000 foot soldiers and 12,000 horsemen are given, but these numbers do not agree with the subsequent breakdown of the troops ( Ab urbe condita libri 37, 40).

- ↑ Polybios, Historíai 21, 25-32; Livy, Ab urbe condita libri 38, 1–11.

- ^ John D. Grainger, The Roman War of Antiochos the Great , Leiden and Boston 2002, p. 339

- ↑ Polybios, Historíai 21, 33-39; Livy, Ab urbe condita libri 38, 12-27; Appian, Syriaka 42.

- ↑ Polybios, Historíai 21, 18-24; Livy, Ab urbe condita libri 37, 53–55.

- ↑ Polybios, Historíai 21, 42; Livy, Ab urbe condita libri 38, 38; Appian, Syriaka 39.

- ↑ AH McDonald: The Treaty of Apamea (188 BC) . In: Journal of Roman Studies . tape 57 , 1967, p. 1-8 .

- ↑ Livius, Ab urbe condita libri 38, 28–29 and 36, 32 respectively.

- ↑ Polybios, Historíai 21, 45; Livy, Ab urbe condita libri 37, 56; Appian, Syriaka 44.

- ↑ Polybios, Historíai 21, 17; Livy, Ab urbe condita libri 37, 45.

- ↑ Polybios, Historíai 6, 2, 2.

- ^ Andreas Mehl, On the diplomatic relations between Antiochus III. and Rome 200-193 BC Chr. , In: Christoph Börker, Michael Donderer (ed.), The ancient Rome and the east. Festschrift for Klaus Parlasca on his 65th birthday , Erlangen 1990, p. 143.

- ^ Livy, Ab urbe condita libri 42, 47.

- ↑ Boris Dreyer, Die Roman Nobilitätsherrschaft and Antiochos III , Hennef 2007, p. 40.

- ^ John D. Grainger, The Roman War of Antiochos the Great , Leiden and Boston 2002, p. 3.