Battle of Magnesia

| date | Winter 190/189 BC Chr. |

|---|---|

| place | Magnesia on Sipylos in Lydia (today: Manisa , Turkey ) |

| output | Victory of the Romans and their allies |

| Parties to the conflict | |

|---|---|

|

Roman Republic ; Kingdom of Pergamon |

|

| Commander | |

| Troop strength | |

| just over 30,000 men | 60,000 infantrymen; 12,000 cavalrymen |

| losses | |

|

300 Roman infantrymen and 24 cavalrymen; |

50,000 infantrymen; 3,000 cavalrymen; 1,400 prisoners |

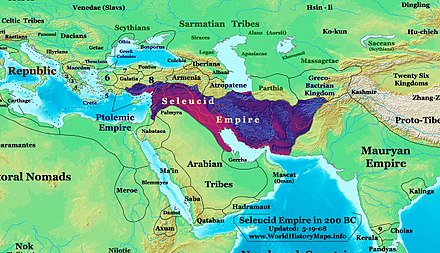

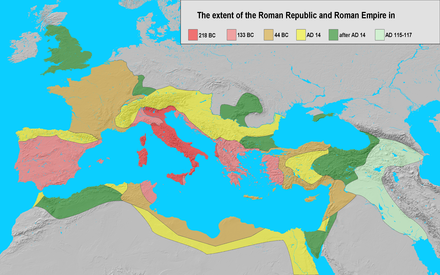

The Battle of Magnesia was 190/189 BC. Near Magnesia ad Sipylum between the Roman Republic under Lucius Cornelius Scipio Asiaticus , his brother Publius Cornelius Scipio Africanus and their ally Eumenes of Pergamon on the one hand and Antiochus the Great , king of the Seleucid Empire , on the other . It was the decisive battle of the Roman-Syrian War and ended with a clear victory for the Romans. This battle showed especially clearly the superiority of the Roman over the Greco- Hellenistic fighting style.

Starting position

Main article: Roman-Syrian War

procedure

The fighters of the right wing of the Seleucid armed forces, personally led by Antiochus, succeeded in defeating the Roman legion and cavalry opposing them and pushing them back in the direction of the Roman camp. In the meantime, however, the Roman allies had succeeded in routing the sickle chariots of the left Seleucid wing, causing some damage to their own cavalry. In the center, on the other hand, the Romans did not engage in a scuffle with the Seleucid phalanx and the war elephants set up here , but instead exposed them to constant fire from their javelins and other long-range weapons.

In this critical phase of the battle, Antiochus made the mistake of pursuing the Romans, who had been defeated on the right wing, into their camp. Instead of rushing to the aid of his center, which slowly began to give way before the strong Roman bombardment and was attacked by the Roman allies on the flank , he let himself be relocated to others by the Romans, who were able to regroup in their camp Engage in combat operations. Left alone, harassed from several sides by the enemy and exposed to constant fire, the Seleucid phalanx finally collapsed and dispersed. The panicked Seleucid war elephants, who trampled quite a few men to death, caused additional losses among those fleeing. Although some Seleucid troops managed to reach their own camp and to defend themselves bitterly with the comrades who had stayed behind, the Romans who pushed after were finally able to slaughter them and conquer the camp.

consequences

The battle of Magnesia was after that of Kynoskephalai (197 BC) the second of three great battles, which revealed the unsuitability of the Greek and Hellenistic warfare of the time against the Rome with alarming clarity. The final end for the phalanx as a decisive tactical formation came with the devastating Macedonian defeat in the Battle of Pydna (168 BC).

For the Seleucid Empire , the defeat at Magnesia was the beginning of the end. In addition to massive reparation payments that Antiochus III. were imposed by the Romans, the king had to 188 BC. In the peace of Apamea BC give up his dominion in Asia Minor and withdraw behind the Taurus Mountains . Ultimately, this victory made it possible for Rome “ - even if this may never have been the collective intention of the Roman elite - to gain a foothold in Asia Minor and wide open the door to the conquest of the Middle East. "

Sources (selection)

Literature (selection)

- Alfred Hirt: Magnesia. Decision on Sipylos. Phalanx, elephants and chariots against Roman legionaries. In: Gerfried Mandl and Ilja Steffelbauer (eds.): War in the ancient world. (= War and Society), Magnus Verlag, Essen 2007, pp. 215-237, ISBN 978-3-88400-520-0 .

Individual evidence

- ↑ Whether the battle in late 190 or early 189 BC It is unclear, but modern literature contains both statements. See generally Peter Green: Alexander to Actium: The Historical Evolution of the Hellenistic Age . Berkeley 1990, p. 421.

- ↑ a b Livius XXXVII 39–40. The question of the extent to which the information on the size of the two armies and the number of casualties correspond to reality has repeatedly been discussed controversially . However, due to the sources, it is not possible to finally obtain clarity.

- ↑ a b Livius XXXVII 41.

- ↑ Hirt (2007), p. 236.