Butcher shop in Schäftlarn on the Isar

|

| Butcher shop in Schäftlarn on the Isar |

|---|

| Lovis Corinth , 1897 |

| Oil on canvas |

| 69 × 87 cm |

| Kunsthalle Bremen |

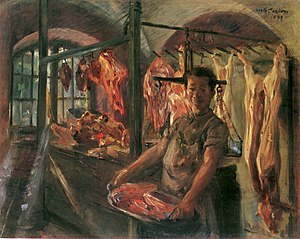

Butcher shop in Schäftlarn on the Isar is a painting by the German painter Lovis Corinth from 1897. The picture shows a scene from the shop of a slaughterhouse in Schäftlarn near Munich . It is owned by the Kunsthalle Bremen .

The painting belongs to a series of genre pictures Corinth on slaughterhouses and butcher shops that in his oeuvre appear several times. These pictures of butchery and meat by Corinth are very often interpreted by various art historians as processing childhood memories as the son of a tanner, or compared and related to the artist's nudes .

Image description

The picture butcher shop in Schäftlarn on the Isar is an oil painting on canvas . It is 69 centimeters high, 87 centimeters wide and signed in two lines in black on the upper right edge of the picture with the name of the painter and the year Lovis Corinth 1897 .

The picture shows a scene in a butcher shop . A smiling young man is standing in a room with a bowl of meat pieces in the foreground in front of a counter with a meat scale hanging on it. Several slaughtered pigs are hung on the counter and on the wall, and other pieces of meat and animal heads lie on the counter. The background is the interior of the slaughterhouse in shades of green and brown, which is illuminated by a window from the background. The image is divided into two equal halves by two vaulted yokes. The animals for slaughter hanging on the wall and the pieces of meat on the counter and in the young man's bowl glow as if they were being illuminated by another light source in the foreground.

According to Horst Uhr's interpretation, the dark color of the background contrasts strongly with the bright multicolor of the pieces of meat on the counter and on the wall, which also get a greasy texture due to the sheen of the color. The division of the picture into two parts by the vault keeps the picture in balance visually in interaction with the red meat pieces and the frame. Hans-Jürgen Imiela described the picture as a view into a low-vaulted room, in which the gutted animals and the body parts on the counter reach into the front area of the picture, where the boy standing there and looking out is holding a trough with pieces of meat. Above all, it underlines the lighting through the window in the background, which results in a clear backlighting effect that particularly emphasizes the picture .

Origin and classification in the work of Corinth

Chronological order

Lovis Corinth painted the picture butcher shop in Schäftlarn on the Isar in 1897 at the end of his studies in Munich. After receiving training in painting in Königsberg and in Munich, Corinth spent almost three years at the Académie Julian in Paris between 1884 and 1887 , where he learned primarily through the neoclassical works of Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres and the Impressionism and pointillism of contemporary French art was influenced. His teachers during this time were William Adolphe Bouguereau and Joseph Nicolas Robert-Fleury . During his time in Paris Corinth took an active part in the art scene; he visited the Salon de Paris , the Paris galleries and museums such as the Louvre . In 1887 Corinth returned to Munich, inspired by the work The Poachers by Wilhelm Leibl exhibited in the Georges Petit art salon .

In 1896, one of the most famous works by Corinth was created in Munich with the self-portrait with a skeleton, and with further pictures from this period Corinth established itself both in the local art scene in Munich and nationally.

At this time, Corinth focused on nude scenes in historical contexts . In the same year as the butcher's shop in Schäftlarn on the Isar , pictures such as The Temptation of Saint Anthony , Susanna and the Two Elderly and The Witches , as well as portraits such as the portrait of the painter Otto Eckmann, were created .

Corinth achieved his greatest success of this time with his Salome , painted in 1900 , a nude painting in a historical setting based on the literary model by Oscar Wilde and showing Salome , daughter of Herodias , with the severed head of John the Baptist . Since this picture was not to be exhibited in the Munich Secession , Corinth gave it to Walter Leistikow in Berlin, who accepted the picture for the exhibition at the Berlin Secession . Due to the great success of the picture, Corinth changed his place of residence shortly afterwards and moved to Berlin.

Content classification - meat

The butcher shop in Schäftlarn on the Isar is one of Corinth's best-known genre paintings that take up the subject of slaughter. He used this theme in a total of 14 paintings, as well as in numerous sketches and graphics such as Slaughtered Pig from 1906, which is in the Museum of Modern Art in New York City .

The representation, the subject , of slaughterhouse scenes and depictions of meat goes back to the beginnings of painting, which are characterized by hunting scenes in cave paintings . The earliest surviving depictions of domestic animal slaughter come from ancient Egypt , for example in the form of relief depictions in the mastaba of Ti , which dates back to around 2400 BC. Is dated during the 5th Dynasty of the Old Kingdom . The subject was also regularly taken up in later cultures, for example in Greek vase painting or in reliefs from the Roman Empire up to the modern age. In Baroque and Rococo painting , the theme was taken up and represented long before Corinth, especially in Italian and Dutch art. For example, the Dutch painter Pieter Aertsen and the Italian artist Annibale Carracci painted several pictures in the 16th century in which pieces of meat and halves of animals are presented in a butcher's shop. Even Rembrandt took up the theme and painted among others the famous image Slaughtered Ox of 1655 that the Louvre is seen in Paris. This picture also inspired Corinth, to whom it was known from his stay in Paris and who thus joined Rembrandt's art-historical tradition. Corinth's contemporaries also took up the subject, including the French François Bonvin with his Das Schwein (Hof des butcher) (1874), Max Liebermann with his butcher's shop in Dordrecht (1877) and Max Slevogt with a slaughtered pig (1906).

Pieter Aertsen : Butcher's Shop with Escape to Egypt , 1551

Annibale Carracci : butcher shop , around 1580

Rembrandt : Slaughtered Ox , 1655

Max Liebermann : Butcher's shop in Dordrecht , 1877

However, due to his childhood, Corinth dealt with the butcher's trade much more intensively and for longer. According to Gert von der Osten , Corinth brought his cattle and butcher scenes to completion before 1890. As early as 1892 he painted a first series of slaughterhouse scenes with the three pictures butchery , cows in the barn and a first version of the slaughtered ox .

1893 followed with the Abattoir his first better-known painting, which, like the painted in the same year the slaughterhouse scene is an animal slaughtered in a darkly lit basement room. Five butchers graze and skin a slaughtered animal on it. Four of the people work on the carcass with tools, while one of the men stands behind a bowl filled with offal and rolls up his sleeves. This picture “skilfully reproduces the mood when skinning a slaughtered ox”. According to Andrea Bärnreuther "[the picture] celebrates the drama of the antagonism of flesh and death". According to them, a “battle on two fronts” takes place here, which is caused by the group of butcher journeyman working on the animal from the front right into the picture and the animal, and the other by the butcher behind the left Animal surrender. She describes the opposing movements of these two scenes that arise in the light. The light, falling through a window in the background, radiates according to her representation "from the escaping life" itself and "unites victims and perpetrators in a common act". The animal's body forms the center of the picture and the plot, and the bloody, "slippery" laughs on the floor of the slaughterhouse create a "sultry atmosphere that is far more appealing than the eye". Friedrich Gross describes the room as a “cave-like basement room” in which “the bright green light of the barred window, broken by the foliage,” emphasizes the “prison-like nature of the scene”, while the wild, form-destroying brush strokes emphasize the violence of slaughter and the white and Spreading red brushstrokes indiscriminately over the carcass and the butcher, over the flesh and skin, and even over the walls. Till Schoofs emphasized the difference between this picture and other pictures of the time: "The energetic broad brushwork and the sketchy character of the picture differ from Corinth's contemporary academic pictures and must have been created in an almost feverish sequence of movements." The slaughtered calf , painted in 1896, shows only the hung carcasses of slaughtered animals in the slaughterhouse.

The butcher shop in Schäftlarn on the Isar takes up the butcher scene in a different way and shows “the typical atmosphere in a butcher shop at the turn of the century”. Alfred Rohde described the picture in 1941 as a brilliant achievement in the continuation of the slaughterhouse theme. and according to Georg Biermann , it is described in 1913 as a "painterly extremely fine picture, which is deeply deepened in color in fine white and red tones". Here, however, the focus is not on the slaughtering and cutting itself, instead a friendly-looking butcher is placed in front of the slaughtered animals, who offers the viewer the fresh meat. After Bärnreuther in this picture is the excitement of slaughter, 1893 At the Abattoir plays a central role, "given way to a calmed, the slaughtered meat to grazing watching". Horst Uhr sees the picture in a more controlled structural logic with a less aggressive character, while Zimmermann points out the boy's “red smile”. In contrast to Max Liebermann's butcher shop in Dordrecht from 1877, the pieces of meat are presented in a less sterile manner with a stronger visual impact.

Von der Osten described this journeyman butcher as "the greatest butcher's representation":

“The journeyman in the butcher's shop is captured most splendidly: the instinctive face with the dusted hair is twisted into a narrow grin and glaringly divided in the slope between the spotlight and shadow. A demon figure on the threshold of the century, who, in its deepest abysses, will also judge man himself by his mere living weight - and yet only a butchery of the Bavarian-rural kind, so self-evident that of all those certainly only the painter, and also the hardly suspecting, writing something on the canvas. "

Friedrich Gross, on the other hand, described the scene in the butcher shop in a friendly manner with goods glowing in the sunlight and a laughing butcher boy who is holding a bowl of juicy pieces of meat in front of him, as it were offering for sale. As in 1892, Corinth combined the picture from the slaughterhouse with a picture from the cattle sheds, in this case with the inside of the barn , which was also created in 1897.

Even after the 1890s, Corinth repeatedly painted pictures depicting slaughterhouses or meat parts. In 1905 another and better-known version of the slaughtered ox was created , which after Zimmermann is the most opulent painting in slaughterhouse pictures. As in the example of Rembrandt, a headless ox hung up by its hind legs and gutted is depicted. Half of the fur was peeled off, so that the bright red flesh is surrounded by the fat, which is clearly shown in white and mother-of-pearl. The butcher and another body are shown inconspicuously in the background.

In 1906 Corinth painted several halves of pork hung on the wall in a butcher shop and in 1913 he depicted the pieces of meat hanging on the wall as "amorphous chunks of meat" in a picture also called a butcher shop.

Around 1925, the year Corinth died, the Belarusian painter Chaim Soutine took up the subject of the slaughterhouse scenes again in Paris and depicted them in an expressionist manner with red and yellow animals and blue "killing apparatus". Another artist who devoted himself to the subject was Norbert Tadeusz , who in 1983 painted a cattle hung up and, in a study of its large-scale limbo - acceptance, gave a slaughtered animal body the shape of a woman. In his Volto Santo, too, the hanging animals have a human shape.

Interpretation and reception

The interpretations for the butcher's shop in Schäftlarn on the Isar refer to various aspects that several critics refer to the entire complex of Corinth's slaughterhouses. The butcher's shop in Schäftlarn on the Isar is usually the focus of attention, together with Im Schlachthaus from 1893 and Schlachteter Ochse from 1905 as the central work of this type. The processing of childhood memories, the fascination with the act of slaughter itself as well as the sensuality of the flesh and thus also the transferred “carnal lust” are named as essential aspects of the interpretation.

Processing of childhood memories

In his book about Corinth in 1955, Gert von der Osten sees it as a liberation from the memories of his youth, "which may have both fascinated and oppressed him." As the son of a tanner, Lovis Corinth had already dealt with slaughtered animals in his childhood, the skins of which his father had processed. He described these memories in his autobiographical writings in various ways, for example when describing the “butchers who wanted to negotiate their freshly stripped skins” and who “came into the house on certain pages: cows and fat pigs had to believe”.

“The slaughter of the large animals was different; I couldn't see the first stage - I was hiding. But then later I didn't see the creature from before and I enjoyed myself. Many a man would scold me if I poked my eyes out of the pig's head and did similar inquisitive things; on the other hand, when the beef was hung up in the attic, it was always viewed with a certain awe and sadness. "

Later, while studying painting at the Königsberg Art Academy , a brother-in-law who worked as a butcher gave him the opportunity to draw and paint in a slaughterhouse. He described this in detail in his autobiographies and especially in the legends from the life of an artist , in which he portrayed himself in the figure of the painter Heinrich. Especially in this work, Corinth described in detail the scenery of the slaughterhouse and the slaughter of an ox, at which "Heinrich" was present and where he could paint them:

“White steam was smoking from the broken bodies of the animals. Guts, red, purple, and mother-of-pearl, hung on iron pillars. Heinrich wanted to paint everything. Sometimes he was roughly pushed aside when carts loaded with rubbish and blood-soaked skins were pushed past him. He ignored it; He did not hear the cracking blows of the axes, the falling of the animals in the zeal of his work. "

In 1996, Jill Lloyd looked at the processing of these childhood memories as well as the choice of themes for the slaughterhouse designers and other motifs as a possible processing of a childhood trauma and compared Corinth with Edvard Munch . In her opinion, the slaughterhouse scenes are “inspired by an extraordinary drama and energy, as if the smell and sight of the blood pouring down from the huge carcasses hanging from the ceiling stimulated a pristine and almost sexual excitement” and are especially stimulated by the Intensity of childhood memories invigorated.

Michael F. Zimmermann , on the other hand, regards the descriptions of Corinth as an "autobiographical myth", a "legend" in which the author Corinth brings his life very close to the reader and at the same time raptures it. Accordingly, “the contrast between butcher's shop and studio, blood-dripping meat and sensual skin” is the representation of the poles between which Corinth stretches out his pictorial narrative in his work, bringing the sitter close to the picture surface, leaving no space for the viewer due to their drastic physical presence for a distanced consideration there. Frédéric Bussmann also emphasizes in his description of the slaughtered ox that Corinth "may have been" memories of his childhood and youth that attracted him to this topic ", but that he" did not paint traumatizing memories ", but rather, he had succumbed to "the charm of the flesh". Schoofs also reflects this on the representation in the legends from the life of an artist .

The act of slaughter and the lust for meat

Imiela viewed the picture butcher shop in Schäftlarn on the Isar as a sounding out of the border position. The backlit display of the room transforms the “animal and human existence” “in a terrifying way” and the boy and the pieces of meat hanging on the walls “get the same quality of things”. In his opinion, Corinth never "undertook such a blurring of borders" again. He also puts up for discussion whether the scales hanging behind the boy in the background allude to this balancing act and thus endow the picture with a death reminder, a vanitas motif, as was very clearly present in Corinth's self-portrait with a skeleton .

According to von der Osten, “killing and being destroyed” as well as the “pale white fat and the dead red of life of the broken open animals” was “above all a festival” for Corinth at that time. Friedrich Gross relates this fascination with the subject of slaughter to the “fundamentally destructive appropriation by humans” and a “predatory lust and the horror of the dismemberment of the living”. The art historian Julius Meier-Graefe went one step further and transferred the foreword to the exhibition catalog of Berlin Secession from 1918 directly applied the act of slaughter to Corinth's painting:

“Sometimes, especially in Berlin, he felt an earthly pleasure in front of the easel like the butcher in front of the cattle ... The human element in art. He slaughtered while he was painting. "

This fascination for the act of slaughter and the pleasure in depicting the meat is also described by other art historians. In the case of the slaughtered ox , Bussmann wrote of the "elaboration of the sensual meat" and went on to describe: "Corinth paints the carcass with sweeping strokes, circles the mass of meat and caresses it almost tenderly with his brush."

Sensuality of the slaughterhouse scenes and relationship to the nudes

According to Gross, the slaughterhouse scenes are characterized by a strong, revealing sensuality , which is particularly evident in the slaughterhouse scene of Im Schlachthaus 1893 and is related to other works by Corinth, especially the nudes and histories. The butcher shop in Schäftlarn on the Isar , on the other hand, is less dramatic, but not less sensual. According to his interpretation, the picture suggests "simple life, abundance, lustful enjoyment, although here too dull gray tones and dark colors limit the permissive sensuality."

The overwhelming majority of authors who describe Corinth's artistic work place the butcher and meat pictures in a direct connection with the nudes for which Corinth was and is very well known. Both groups are assigned a sensuality that connects these motifs. In this aspect Corinth was compared primarily with the baroque painters Peter Paul Rubens and Jacob Jordaens . Jill Lloyd places the dead animal bodies, which "are brought to life, as it were, by the virtuosity and sensuality of Corinth's color", in direct relation to the women in the nudes, since Corinth treats both motifs "breathing close" and not as still lifes. She attributes this “strange and in a certain way morbid association” to “the magnetic attraction that the colors and textures of the flesh exerted on the artist's eyes”.

According to Zimmermann, there is a clear connection in Corinth's work between the depiction of slaughterhouse scenes and the interest in the depiction of naked bodies and the incarnate , the skin color of the depicted, with the flesh underneath. He puts the depictions in a connection with the Innocentia of 1890 and other "works in which Corinth brings together one or more female nudes, some of which hold their breasts and thus make the softness of the flesh almost palpable." he enumerates in this context The Witches (1897), The Harem (1904) and The Arms of Mars (1910). Nudes outside of historical representations are also related to the battle pictures, for example the painting The Nudity , created in 1908 and thus parallel to Slaughtered Ox , in which Corinth portrayed his wife Charlotte Berend-Corinth together with their twice-painted son Thomas. Zimmermann compares the color of his wife's body directly with the slaughtered ox : “The skin is always glowing red, as if from overflowing vitality, but the swellings shimmer like mother-of-pearl in white. One could not have come closer to the tones of the ox in nude painting. "

For the treatment of the subject of meat and the relationship between Corinth's depictions of meat and nudes, Zimmermann comes to the following conclusion:

“More than any other artist, Corinth combines his sensitivity for the incarnates, for the bare, living flesh without a shell, with a fascination for dead flesh. In his painting, he encounters the model with an eroticism that mixes violence. Painting appears as an act that is always violent, as well as an inadmissible intrusion into the intimacy of the other. "

Exhibitions and provenance

The picture butcher shop in Schäftlarn on the Isar was painted by Corinth in 1897 at the end of his studies in Munich. The painting was in the possession of the Berlin art dealer and collector Ernst Zaeslein , from whom it acquired the Kunsthalle Bremen in 1913 (inv. No. 347 - 1913/3). The then director Gustav Pauli , like Hugo von Tschudi in the National Gallery in Berlin, built up a collection of contemporary art and acquired paintings by Paula Modersohn-Becker as well as by French and German impressionists . The acquisitions include Camille in a green dress by Claude Monet , Zacharie Astruc by Édouard Manet and paintings by Gustave Courbet , Pierre-Auguste Renoir , Camille Pissarro , Max Liebermann and Max Slevogt . In 1911 the purchase sparked the poppy field it from Van Gogh to Bremer Artist dispute among painters and museum people in Germany. The acquisitions also included some pictures by Lovis Corinth.

Butcher shop in Schäftlarn on the Isar hangs in the permanent exhibition of the Kunsthalle Bremen and was also shown in numerous national and international exhibitions , especially in the period after the Second World War . According to the catalog raisonné by Charlotte Berend-Corinth , it was part of an exhibition in the Landesmuseum Hannover in 1950 and in the Museum zu Allerheiligen in Schaffhausen in 1955. In 1958, on the occasion of the 100th birthday of Lovis Corinth, the picture was shown in the National Gallery in Berlin, the Kunsthalle Bremen and the Kunstverein Hanover exhibited. In 1960 it was shown in the New Gallery of the City of Linz and in 1975 for the first time in the United States in the Gallery of Modern Art in New York City . In 1975 an exhibition followed in the Städtische Galerie im Lenbachhaus in Munich and in 1976 in the Kunsthalle Cologne . As part of the exhibition "German Masters of the Nineteenth Century", the Metropolitan Museum of Art showed the picture again in New York in 1981. Further exhibitions took place in 1985/1986 at the Museum Folkwang in Essen, 1992 at the Kunstforum Wien and 1992/1993 at the Lower Saxony State Museum in Hanover. In 2010, the picture was also shown in the exhibition "A feast for the eyes - From eating in a still life" at the Bank Austria Kunstforum in Vienna.

supporting documents

- ↑ a b c butcher shop in Schäftlarn on the Isar, 1897 In: Charlotte Berend-Corinth : Lovis Corinth: The paintings . Revised by Béatrice Hernad. Bruckmann Verlag, Munich 1992; BC 147, p. 75. ISBN 3-7654-2566-4 .

- ↑ a b c d Horst clock : Lovis Corinth. University of California Press 1990; P. 107.

- ^ A b Andrea Bärnreuther: Butcher shop in Schäftlarn on the Isar, 1897. In: Peter-Klaus Schuster , Christoph Vitali, Barbara Butts (eds.): Lovis Corinth . Prestel Munich 1996; P. 131. ISBN 3-7913-1645-1 .

- ↑ a b c d e Hans-Jürgen Imiela : Introduction .. In: Charlotte Berend-Corinth: Lovis Corinth: The paintings. Revised by Béatrice Hernad. Bruckmann Verlag, Munich 1992, ISBN 3-7654-2566-4 , p. 23.

- ↑ a b c Zdenek Felix : The career of an outsider. In: Zdenek Felix (Ed.): Lovis Corinth 1858–1925. Publication for the exhibition in the Folkwang Museum Essen (November 10, 1985 - January 12, 1986) and in the Kunsthalle der Hypno-Kulturstiftung Munich (January 24 - March 30, 1986), DuMont Buchverlag, Cologne 1985; Pp. 17-18. ISBN 3-7701-1803-0 .

- ↑ Barbara Butts: Slaughtered pig In: Peter-Klaus Schuster , Christoph Vitali, Barbara Butts (ed.): Lovis Corinth . Prestel Munich 1996; Pp. 336-337. ISBN 3-7913-1645-1 .

- ^ Kurt Nagel, Benno P. Schlipf: The butcher's trade in the fine arts. Art history of the butcher's trade. Verlag CF Rees, Heidenheim 1982; P. 57.

- ^ Kurt Nagel, Benno P. Schlipf: The butcher's trade in the fine arts. Art history of the butcher's trade. Verlag CF Rees, Heidenheim 1982; Pp. 58-59.

- ^ Kurt Nagel, Benno P. Schlipf: The butcher's trade in the fine arts. Art history of the butcher's trade. Verlag CF Rees, Heidenheim 1982; Pp. 59-61.

- ↑ a b c d Frédéric Bussmann: Geschlachteter Ochse, 1905. In: Ulrike Lorenz , Marie-Amélie zu Salm-Salm , Hans-Werner Schmidt : Lovis Corinth and the birth of modernity catalog on the occasion of the retrospective for the 150th birthday of Lovis Corinth ( 1858–1925) in Paris, Leipzig and Regensburg. Kerber Verlag, Bielefeld 2005, ISBN 978-3-86678-177-1 ; Pp. 162-163.

- ↑ a b c d e f Gert von der Osten : Lovis Corinth. Verlag F. Bruckmann, Munich 1955; Pp. 50-51.

- ^ Butchery , 1892. In: Charlotte Berend-Corinth: Lovis Corinth: The paintings. Revised by Béatrice Hernad. Bruckmann Verlag, Munich 1992, ISBN 3-7654-2566-4 , BC 87, p. 67. ISBN 3-7654-2566-4 .

- ^ Cows in the stable, 1892. In: Charlotte Berend-Corinth: Lovis Corinth: The paintings. Revised by Béatrice Hernad. Bruckmann Verlag, Munich 1992, ISBN 3-7654-2566-4 , BC 88, p. 67. ISBN 3-7654-2566-4 .

- ^ Slaughtered ox, 1892. In: Charlotte Berend-Corinth: Lovis Corinth. The paintings. Revised by Béatrice Hernad. Bruckmann Verlag, Munich 1992, ISBN 3-7654-2566-4 , BC 89, p. 68.

- ^ In the slaughterhouse, 1893. In: Charlotte Berend-Corinth: Lovis Corinth: The paintings. Revised by Béatrice Hernad. Bruckmann Verlag, Munich 1992, ISBN 3-7654-2566-4 , BC 103, p. 69.

- ^ Slaughterhouse scene , 1893. In: Charlotte Berend-Corinth: Lovis Corinth: The paintings. Revised by Béatrice Hernad. Bruckmann Verlag, Munich 1992, ISBN 3-7654-2566-4 , BC 102, p. 69.

- ↑ a b Kurt Nagel, Benno P. Schlipf: The butcher's trade in the visual arts. Art history of the butcher's trade. Verlag CF Rees, Heidenheim 1982; Pp. 122-123.

- ↑ a b c d e f Friedrich Gross : The sensuality in Corinth's painting. In: Zdenek Felix (Ed.): Lovis Corinth 1858–1925. Publication for the exhibition in the Folkwang Museum Essen (November 10, 1985 - January 12, 1986) and in the Kunsthalle der Hypno-Kulturstiftung Munich (January 24 - March 30, 1986), DuMont Buchverlag, Cologne 1985; P. 43. ISBN 3-7701-1803-0 .

- ↑ Andrea Bärnreuther: In the slaughterhouse, 1893. In: Peter-Klaus Schuster , Christoph Vitali, Barbara Butts (ed.): Lovis Corinth . Prestel Munich 1996; Pp. 130-131. ISBN 3-7913-1645-1 .

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i slaughterhouse and nude, blood and incarnate. In: Michael F. Zimmermann : Lovis Corinth. Beck Wissen series bsr 2509. CH Beck, Munich 2008, ISBN 978-3-406-56935-7 ; Pp. 41-51.

- ↑ a b c d e f Michael F. Zimmermann : Corinth and the meat in painting. In: Ulrike Lorenz , Marie-Amélie zu Salm-Salm , Hans-Werner Schmidt : Lovis Corinth and the Birth of Modernism Catalog on the occasion of the retrospective for the 150th birthday of Lovis Corinth (1858–1925) in Paris, Leipzig and Regensburg. Kerber Verlag, Bielefeld 2005, ISBN 978-3-86678-177-1 ; Pp. 320-328.

- ↑ Till Schoofs: Im Schlachthaus, 1893. In: Ulrike Lorenz , Marie-Amélie zu Salm-Salm , Hans-Werner Schmidt : Lovis Corinth and the Birth of Modernism Catalog on the occasion of the retrospective for the 150th birthday of Lovis Corinth (1858–1925) in Paris, Leipzig and Regensburg. Kerber Verlag, Bielefeld 2005, ISBN 978-3-86678-177-1 ; Pp. 160-161.

- ^ Slaughtered calves, 1896. In: Charlotte Berend-Corinth: Lovis Corinth: The paintings. Revised by Béatrice Hernad. Bruckmann Verlag, Munich 1992, ISBN 3-7654-2566-4 , BC 128, p. 73.

- ^ Alfred Rohde : The young Corinth. Rembrandt-Verlag, Berlin 1941; P. 142.

- ^ Georg Biermann : Lovis Corinth. Artist Monographs 107, published by Velhagen and Klasing, Bielefeld and Leipzig 1913; P. 44.

- ↑ a b c d e Jill Lloyd: Announcement of mortality In: Peter-Klaus Schuster , Christoph Vitali, Barbara Butts (ed.): Lovis Corinth . Prestel Munich 1996; Pp. 70-71. ISBN 3-7913-1645-1 .

- ↑ stable Affairs, 1897. In: Charlotte Berend-Corinth: Lovis Corinth: The paintings. Revised by Béatrice Hernad. Bruckmann Verlag, Munich 1992, ISBN 3-7654-2566-4 , BC 146, p. 75.

- ^ Slaughtered ox, 1905. In: Charlotte Berend-Corinth: Lovis Corinth: The paintings. Revised by Béatrice Hernad. Bruckmann Verlag, Munich 1992, ISBN 3-7654-2566-4 , BC 318, p. 101.

- ^ Butcher shop, 1905. In: Charlotte Berend-Corinth: Lovis Corinth: The paintings. Revised by Béatrice Hernad. Bruckmann Verlag, Munich 1992, ISBN 3-7654-2566-4 , BC 330, p. 103.

- ^ Butcher shop, 1913. In: Charlotte Berend-Corinth: Lovis Corinth: The paintings. Revised by Béatrice Hernad. Bruckmann Verlag, Munich 1992, ISBN 3-7654-2566-4 , BC 587, p. 143.

- ↑ a b c d Friedrich Gross : The sensuality in Corinth's painting. In: Zdenek Felix (Ed.): Lovis Corinth 1858–1925. Publication for the exhibition in the Folkwang Museum Essen (November 10, 1985 - January 12, 1986) and in the Kunsthalle der Hypno-Kulturstiftung Munich (January 24 - March 30, 1986), DuMont Buchverlag, Cologne 1985; Pp. 44-46. ISBN 3-7701-1803-0 .

- ^ A b Lovis Corinth : "Artists Erdenwallen" Collected writings. Berlin: Fritz Gurlitt, 1920.

- ^ Lovis Corinth : Legends from the artist's life 2nd edition, Berlin: Bruno Cassirer, 1918.

- ^ A b Julius Meier-Graefe : Lovis Corinth. Exhibition catalog of the Berlin Secession, Berlin 1918; quoted from Andrea Bärnreuther: Im Schlachthaus, 1893. In: Peter-Klaus Schuster , Christoph Vitali, Barbara Butts (eds.): Lovis Corinth . Prestel Munich 1996; Pp. 130-131. ISBN 3-7913-1645-1 .

- ↑ Friedrich Gross : The sensuality in Corinth's painting. In: Zdenek Felix (Ed.): Lovis Corinth 1858–1925. Publication for the exhibition in the Folkwang Museum Essen (November 10, 1985 - January 12, 1986) and in the Kunsthalle der Hypno-Kulturstiftung Munich (January 24 - March 30, 1986), DuMont Buchverlag, Cologne 1985; Pp. 46-48. ISBN 3-7701-1803-0 .

- ^ Butcher shop in Schäftlarn in the online catalog of the Kunsthalle Bremen .

- ^ Gustav Pauli (1899–1914) on the website of the Kunsthalle Bremen .

- ^ Zdenek Felix (Ed.): Lovis Corinth 1858-1925. Publication for the exhibition in the Folkwang Museum Essen (November 10, 1985 - January 12, 1986) and in the Kunsthalle der Hypno-Kulturstiftung Munich (January 24 - March 30, 1986), DuMont Buchverlag, Cologne 1985. ISBN 3-7701-1803 -0 .

- ↑ Silke Osman: A feast for the eyes from five centuries . Preussische Allgemeine Zeitung, March 28, 2010.

literature

- Butcher shop in Schäftlarn on the Isar, 1897 In: Charlotte Berend-Corinth : Lovis Corinth: The paintings . Revised by Béatrice Hernad. Bruckmann Verlag, Munich 1992; BC 147, p. 75. ISBN 3-7654-2566-4 .

- Friedrich Gross : The sensuality in Corinth's painting. In: Zdenek Felix (Ed.): Lovis Corinth 1858–1925. Publication for the exhibition in the Folkwang Museum Essen (November 10, 1985 - January 12, 1986) and in the Kunsthalle der Hypno-Kulturstiftung Munich (January 24 - March 30, 1986), DuMont Buchverlag, Cologne 1985; Pp. 39-55. ISBN 3-7701-1803-0 .