Snakebite

| Classification according to ICD-10 | |

|---|---|

| X20 | Contact with poisonous snakes or lizards |

| ICD-10 online (WHO version 2019) | |

A snake bite is understood to be a bite injury that was caused by a venomous snake and in which the release of poison leads to poisoning . Snakes usually bite to overwhelm their prey , but also for defense. There is also a secondary risk of infection .

However, poison is not always released when a poisonous snake bites, but it can always be assumed until it is proven. In about half of the cases there is a so-called dry bite , in which no poison gets into the wound. It is believed that snakes often bite "without poison" when defending themselves in order not to waste it. However, it is also possible that the snake inadvertently released the venom before its teeth have penetrated the attacker's skin.

The adder and aspic viper , which are native to German-speaking countries, can also cause symptoms of poisoning, especially life-threatening allergic reactions.

First aid / countermeasures

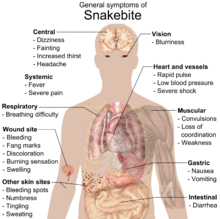

The venom of a venomous snake acts either on the central nervous system , i.e. neurotoxic , or on the blood and tissue ( hemotoxic ), in some species of snakes such as the Gaboon viper , both. Neurotoxic poisons have a paralyzing effect and limit the function of the respiratory organs, which can lead to death by suffocation. Hemotoxic toxins attack the blood cells and tissues.

After a snakebite, it is important to immobilize the affected part of the body. Local disinfection of the bite site makes sense. Fighting shock is necessary if the poison has a circulatory effect. A pressure / immobilization technique is only used when certain types of venomous snakes are bitten.

In no case should any further manipulations such as sucking out, cutting out or binding be carried out. By opening the wound, snake venom can lead to bleeding of the bitten person, because the bite wound is not on the surface, but the venom is deposited about 3 cm deep in the tissue. The wound would also have to be cut open 3 cm deep, which means that the victim can bleed to death. Attempting to vacuum the skin hardly leads, or only to a small extent, to the desired success. Any manipulation of the bitten limb only causes the poison to get into the bloodstream faster due to the increased pulse. According to the latest findings, binding, congestion of the blood or a pressure bandage are not effective.

The site of the bite should be marked with a felt pen, the time noted and the progression of the swelling every 30 minutes should also be marked in order to get an indication of the progression of the poisoning. The appearance of the snake should be recorded as precisely as possible. Only in the case of unknown snakes this should be given to the patient for further treatment by the doctor. You should refrain from killing the snake to avoid harming yourself. Even with a second bite, venomous snakes can release enough venom to harm another person.

If symptoms occur, the patient should be observed in hospital for at least 24 hours; if there is swelling, decongestant measures should be taken (cold compresses on the bite site), tetanus prophylaxis and blood coagulation and circulatory monitoring should take place. An antivenin -Gabe found only in increasing and more pronounced symptoms or acute poisoning instead. In any case, the poison control center should be contacted, possibly a doctor or the emergency room.

prevention

In areas known for venomous snakes, the following is advised:

- Wear sturdy footwear with a shaft as far as possible over the ankle, as well as "snake gaiters", a type of gaiter .

- Put a walking stick in front of your feet, do not step into bushes or walk through bushes.

- Stand firm, snakes are roused by it.

- Never corner or touch snakes. Most accidents occur through “playing” and touching.

- If the snake makes threatening gestures, immediately step back slowly and allow the snake to escape.

It should also be noted that the severed head of a snake that has been killed in this way still shows a bite reflex for a certain time and can thus trigger a bite and poisoning.

frequency

Because many snake bites are not reported, there is no accurate data on the frequency of snake bites for many regions of the world. It is estimated that around 2.5 million bites per year, of which around 125,000 are fatal. Globally, most venomous snake bites happen in warm seasons, especially April and September when snakes are very active and many people are outdoors. Agricultural and tropical regions are hardest hit. Most of the victims are male and between 17 and 27 years old (Wingert & Chan 1988). In many regions of the world, for example in Africa, there is not enough serum available for treatment.

Situation in the USA

A study from the 1950s estimated that approximately 45,000 bite accidents occur in the United States annually . However, only about 7,000 to 8,000 of these are caused by poisonous snakes. Only about 10 snakebites a year lead to death. So the chance of surviving a bite is around 99.8%. The majority of these bites occur in the southwest of the USA, in the east the incidence of rattlesnakes is significantly lower. Most fatal bite accidents are caused by Texas rattlesnakes and diamond rattlesnakes . Children and the elderly are particularly at risk. Most reported snake bites are 19 bites per 100,000 residents in the state of North Carolina . The average for the entire United States is only about 4 bites per 100,000 population per year (Russell 1980).

Situation with other peoples

In other countries with larger snake populations and poorer medical care, the risk of death is higher. It is estimated that 5.4 million people are bitten by poisonous snakes or, also common, have poison injected into their eyes every year. This leads to 400,000 disabilities such as amputations or blindness and 80,000 to 138,000 deaths worldwide. In India , 50,000 of 2.8 million people attacked (1.8%) die, in Nepal 1,000 of 20,000 (5%), and among the Aché in Paraguay , an indigenous indigenous people, 14% of adult men die of snake bites.

literature

- Barry S. Gold, Willis A. Wingert et al .: Snake venom poisoning in the United States: A review of therapeutic practice . In: Southern Medical Journal , June 1994, 87 (6): 579-89.

- Barry S. Gold, RA Barish: Venomous snakebites: current concepts in diagnosis, treatment, treatment, and management . In: Emerg Med , Clin North Am 1992; 10: 249-67.

- CS Kitchens, LHS Van Mierop: Envenomation by the eastern coral snake (Micrurus fulvius fulvius): a study of 39 victims . In: JAMA 1987; 258: 1615-8.

- Kurecki, Brownlee, et al .: The Journal of Family Practice , 1987, 25 (4): 386-392

- Disaster Recovery Fact Sheet "How to Prevent or Respond to a Snake Bite" , Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, April 26, 2006

- HM Parrish: Incidence of treated snakebites in the United States. In: Public Health Rep . 1966; 81: 269-76.

- cf Postgrad Med , 1987, Oct; 82 (5): 32; Postgrad Med , 1987, Aug; 82 (2): 42; Ann Emerg Med , 1988, Mar; 17 (3): 254-256; Toxicon , 1987; 25 (12): 1347-1349; Ann Emerg Med , 1991, Jun; 20 (6): 659-661.

- Riggs et al .: Rattlesnake evenomation with massive oropharyngeal edema following incision and suction (Abstract) AACT / AAPCC / ABMT / CAPCC Annual Scientific Meeting, 1987.

- Findlay E. Russell: Ann Rev Med , 1980, 31: 247-59.

- Findlay E. Russell: Snake venom poisoning . Great Neck, NY: Scholium, 1983: 163.

- Findlay E. Russell: When a snake strikes . In: Emerg Med , 1990; 22 (12): 20-5, 33-4, 37-40, 43.

- Suction for Venomous Snakebite: A Study of 'Mock Venom' Extraction in a Human Model . In: Annals of Emergency Medicine . February 2004, p. 181.

- JB Sullivan, WA Wingert, RL Norris Jr .: North American Venomous Reptile Bites. Wilderness Medicine: Management of Wilderness and Environmental Emergencies , 1995; 3: 680-709.

- US Food and Drug Administration (November 2002) For Goodness Snakes! Treating and Preventing Venomous Bites . Retrieved December 30, 2005.

- Willis A. Wingert und L. Chan: Rattlesnake bites in southern California and rationale for recommended treatment . In: West J Med , 1988; 148: 37-44.

- World Health Organization. Animal sera . Retrieved December 30, 2005.

- Jeff J. Boyd et al .: Venomous Snakebite in Mountainous Terrain: Prevention and Management (PDF, 389 kB), Wilderness and Environmental Medicine, 18, 2007, pp. 190-202

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b Archived copy ( memento of the original from April 23, 2006 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Texan suffered bite from severed snakehead orf.at, June 7, 2018, accessed June 7, 2018.

- ↑ http://www.who.int/bloodproducts/animal_sera/en/

- ↑ Ilona Eveleens: Deadly Snake Bites : The Forgotten Disease . In: The daily newspaper: taz . August 29, 2018, ISSN 0931-9085 ( taz.de [accessed September 10, 2018]).

- ↑ Archived copy ( memento of the original dated September 23, 2006 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ Gold & Wingert 1994

- ↑ GEO 11/2019, p. 143: Bernhard Kegel: Giftzwerge