Transylvanian Saxony

The Transylvanian Saxons are a German-speaking minority in today's Romania who speak the relict dialect Transylvanian-Saxon . They have been living in the Transylvania part of the country since the 12th century , making them the oldest German settler group still in existence in Eastern Europe . Their settlement area lies outside the contiguous German-speaking area and has never been connected to Imperial German territory.

Transylvania developed as part of the Kingdom of Hungary from the 12th century . After the partition of Hungary in 1540, as the Principality of Transylvania under the sovereignty of the Ottoman Empire, it was largely autonomous, at least domestically. During the Great Turkish War , the Habsburgs occupied the principality and incorporated it into the Habsburg Monarchy in the Treaty of Karlowitz in 1699 . After the defeat of Austria-Hungary in World War I , the Karlsburger National Assembly proclaimed the unification of Transylvania with the Romanian Empire on December 1, 1918 . The Transylvanian Saxons welcomed the connection to Romania in the Medias declaration of affiliation in February 1919. In 1920 the incorporation of Transylvania into the Romanian state was enshrined in the Treaty of Trianon .

While around 300,000 Transylvanian Saxons lived in Transylvania in 1930, in 2007 there were only 15,000. The vast majority emigrated to the Federal Republic of Germany in particular , but also to Austria , since the 1970s and in a major surge from 1990 . Organized communities of Transylvanian Saxons also live in significant numbers overseas in Canada and the USA .

Name origin

The name Saxony probably goes back to a linguistic misunderstanding. A small part of the settlers were referred to as Saxones in the Latin chancellery language of the Hungarian kings . In relation to Transylvania, this term was first used in 1206 in a document from the Provost of Weissenburg and referred to the residents of Krakow , Krapundorf and Rumes in the Unterwald as primi hospites regni ( German: the first guests of the empire ).

The Saxones mentioned were people "... quos et nobilitas generis exornat et provida priorum regum deliberatio acceptiores habuisse dignoscitur et digniores ..." ( German ... who, among other things, also distinguishes the nobility of their descent, which was also valued and appreciated by the earlier kings excellent ... ). Presumably they are ministerial aristocrats who were called servientes regis ( German servants of the king ) in Hungary around 1200 , but in the German Empire as milites ( German knights, soldiers ). In the document they received classic nobility rights in business, viticulture, pig and cattle breeding, exemption from taxes and exemption from the war levy ( Latin collectae ). Karako (Cracow) and Crapundorph (Krapundorf) were also mentioned separately in a royal document in 1225. There the Germans of these places were exempted from the wine tariff. The Saxones mentioned there should not be confused with those from the Sibiu province .

People were also mentioned by name in the comments on documents from this period, such as Saxo Fulco around 1252, who owned the Zekesch area ( Latin terra Zek ) and who died with his family during the Mongol storm in 1241/42. Likewise, around 1291 Syfrid von Krakau , Jakob von Weißenburg , Herbord von Urwegen and Henc von Kelling were named, who rebuilt the roof structure of the burned Weissenburg cathedral church and were paid for it with 90 silver marks and 24 yards of Dorner cloth. According to the royal charter, these people were "quos et nobilitas generis exornat ..." ( German, therefore, people who are distinguished, among other things, by their aristocratic origin ). Furthermore, like the Saxones in the deed of 1206, they would have been honored under earlier kings and considered worthy of distinction ( Latin ... et provida priorum regum deliberatio acceptiores habuisse dignoscitur et digniores. ). So there were no peasant settlers from the Altland who were then still listed in the scriptures as Flandrenses ( German Flanders ) or Hospites Theutonicci ( German German guests ).

The term Saxones therefore meant a status and not a primarily ethnic classification. All knights or German weapon bearers were meant. These armed men were mentioned as early as 1152. King Geisa II. Moved at this time with an army of Czechs and Saxones against the Byzantine Emperor Manuel I in the war. King Andreas II also surrounded himself in 1217 on a trip to the Holy Land with an army from Hungary and German soldiers, Saxones . Similar references to Saxones as an armed man emerged from documents from 1210, which mentioned military formations that the Hermannstadt Count Joachim sent into the field during a war against the Bulgarians. Another document from 1230 describes the duty of military service of the hospitibus Theutonicis de Zathmar Nemeti residentibus ( German of the German guests of Sathmar ), who had to put more Saxonum in the king's exile. Transylvanian Saxons cannot have been meant by this.

The denomination of status only spread over the centuries as a term of legal language to the entire group of settlers and ultimately became a self-denotation. The latter, however, was up into modern times in the dialect Detsch or daitsch , so German and not Saxon or in dialect saksesch . In German, high-language documents from Transylvania it is also called German . However, there is no semantic contrast between saksesch and dsch . The terms were and are used synonymously.

The name has nothing to do with the Free State of Saxony in today's Germany. It was also not a blanket term in which all Germans were referred to as Saxons. A German was called Német in the Hungarian language , but a Saxon from Transylvania was called Szász .

Origin and settlement

The areas of origin of the settlers were mostly in the areas of the bishoprics of Cologne , Trier and Liège (today between Flanders , Wallonia , Luxembourg , Lorraine , Westerwald and Hunsrück up to the Westphalian region ). Some of the settlers (in northern Transylvania ) also came from Bavaria . However, the majority came from the Middle Rhine and Moselle Franconian regions . This group of settlers was by no means homogeneous, but included, in addition to the German-speaking groups, also Old French- speaking Walloons (in the documents these are called Latini ) and Dutch.

The folk legend describes the settlement as a process in which the settlers who would have had it very badly in their homeland (which actually coincides with reports of famine and epidemics from the first half of the 12th century in the dioceses of Trier and Liège ) would have found their way to Transylvania on their own initiative. At the first resting place in Transylvania, the settlers would have consulted (where Sibiu is today ). As a sign of taking possession of the land, the two leaders Hermann and Wolf (in some legends he is also called Croner ) are said to have thrust two large swords crossed into the ground. These crossed swords formed the coat of arms of Sibiu from that time . The groups of settlers would then have split up and advanced north and east. Each group kept a sword and should guard it carefully, because the loss of the sword would mean the loss of the land (sometimes there is also talk of a sword and an iron shirt). Some came to Broos , others to Draas . In doing so, they would have founded a large number of towns and cleared the land. The first group, however, lost their sword (or iron shirt) and their country was then ravaged by the Turks and was therefore lost. The second group kept their sword better and therefore kept the land in their possession.

This event was for centuries (and is partly still today) strongly reshaped and influenced by the formation of legends, but it contains a core of truth, as it describes the process of the settlement of southern Transylvania as a myth and includes the removal of the population of the Brooser Stuhl by the Turks around 1420. However, these prosaic scenarios are considered refuted in modern historical research and are in part due to the efforts of the historiography of the 19th century. History was seen as a political weapon in the fight against Hungarian attempts at appropriation, which were perceived as extremely threatening after the dissolution of Königsboden and the University of Nations in 1878, as the Hungarian nationality legislation provided for the Magyarization of all peoples in the Hungarian part of the Empire .

The arrival of the Transylvanian Saxons happened as part of the German settlement in the east . The settlers were professionally recruited by locators and emigrated to Transylvania in several batches. Their way has led them over Silesia , Saxony or Bohemia (an intermediate home was assumed there) over the Spiš to Transylvania, or over the Danube and the Mieresch upwards. The first settlements took place around 1150 under King Géza II.

In addition, they were not the only Germans in Hungary at the time, as the kings had called German nobles, civil servants, craftsmen, miners and farmers to various parts of their empire several times since Stephen II . The settlement of the Transylvanian Saxons is part of this development.

The settlement took place according to set priorities, so villages and towns were founded and inland settlement was promoted. The first 13 primary settlements in the Sibiu chapter were Hermannstadt , Stolzenburg , Großschünsch , Burgberg , Hammersdorf , Neppendorf and Schellenberg , in the Leschkirch chapter they were Alzen , Kirchberg and Leschkirch as well as Großschenk , Mergeln and Schönberg in the Schenker chapter. Even the number of the first settlers can be calculated by researching the field and hoof division of Saxon communities. The settlements initially consisted of an always the same number of slightly more than 40 hooves, i.e. H. approx. 40 farms. 13 settlements with 40 hooves each results in 520 hooves (farm areas). Assuming an average family size of five people, a conservative estimate results in a number of 2,600 people. Further immigration in the course of the following years and decades (also from the areas of origin) is likely. Over time, settlers poured from the primary locations into new foundations and less developed areas. The Königsboden , Burzenland and Nösnergau were settled from the Hermannstadt, Leschkirch and Großschenk chairs . In addition, there was also internal settlement on Adelsboden .

Only in the course of the centuries did this colorful community of settlers develop into a real people with its own cultural memory , language, law ( own land law ) and autonomous administration ( nation university ).

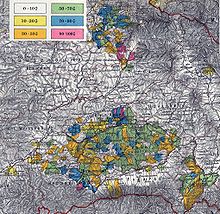

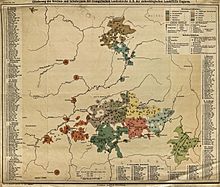

area

The Transylvanian Saxons settled in three non-contiguous areas of the medieval principality of Transylvania: Altland , Nösnergau and Burzenland . These were subdivided into even smaller administrative units that lasted well into the 19th century.

There were also other unofficial Saxon region names that did not necessarily match the administrative units, e.g. B. Weinland (around Mediasch), Repser Ländchen , Unterwald , Reener Ländchen , Krautwinkel, Harbachtal etc.

The old regional authorities were based on the ethnic and legal affiliation of the Saxon residents and together formed the royal floor . However, this does not correspond to the current borders of the Hunedoara , Alba , Hermannstadt , Kronstadt , Mureș and Bistritz districts , which all contain parts of the Königboden.

Privileges and dominance

The importance of the Transylvanian Saxons in their region can only be deduced from history. Most of the important cities and towns in Transylvania were founded by the Transylvanian-Saxon settlers. To this day, its cultural assets and historical buildings shape the image of Transylvania. Their cultural and economic dominance lasted well into the 20th century and did not end until the communists came to power in Romania in 1944/45. This also included the ownership of land and forests that were largely owned by the German minority in the settlement areas of the Transylvanian Saxons until the end of the Second World War (with the exception of the properties of the University of Nations , which had already been nationalized).

The settlers owed this outstanding position to a number of privileges, some of which they had already received during the settlement period and especially after the award of the golden charter and the establishment of the royal floor. These were originally intended to promote the economic achievements of the settlers and thus generate the highest possible tax revenues for the Hungarian crown.

Over the centuries, the privileges and rights were constitutive for the settler community and were successfully defended against state interference until the end of the 19th century. These legal peculiarities gave rise to a sense of class and nationality, which was additionally supported by de facto autonomy that had been in force for centuries for the Transylvanian Saxons. The national university as an organ of self-administration and the right to own land as codified customary law of the settlers were two important guarantees for this special position, from which certain historical and cultural achievements of the Transylvanian Saxons on the one hand and their existence in an often hostile environment over such a long time on the other hand explain.

The assessment of the role of the Transylvanian Saxons in Transylvania was and still is dependent on national perspectives. In particular, at the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th century, a dispute arose between Hungarians, Romanians and Transylvanian Germans about the shares of the individual nations in the development of Transylvania. This was intended to legitimize territorial claims - especially on the part of Hungary and Romania - historically. In retrospect, however, this undertaking is to be viewed as very dubious, especially for the Romanians, as such efforts resulted in a rigid, anti-minority policy.

Even after the final abolition of Königsboden, Nations University and Eigenlandrecht in 1876, the Transylvanian Saxons owned most of the means of production, industries and resources in their ancestral territory. In addition, regular contacts and exchanges with the German language and culture have existed since the time of settlement . To study, the Transylvanian Saxons traditionally went to the universities in Vienna or in Central Germany and from there constantly brought new, western ideas (classic examples would be Reformation and book printing ), standards and technologies with them. This meant that they were often far superior to the other ethnic groups in Transylvania, even without their special rights.

The situation changed fundamentally when the Iron Curtain stopped this exchange and the property of the Transylvanian Saxons was confiscated in large-scale forced collectivization and expropriation measures by the communists and the ethnic group was deprived of rights through targeted discrimination against the Romanian state after the end of the Second World War.

Social specifics

Neighborhoods

The neighborhoods , especially in the villages, were an archaic form of social security. However, after the Second World War, this only applied to a limited extent and to a limited extent. However, the concept of neighborhood and certain parts of the old customs were alive until the emigration, whereby the institution of neighborhood largely dissolved within a few decades due to the consequences of communism, industrialization and the gradual breakdown of village structures.

The neighborhoods could be classified as a kind of farmers' guild, which, however, only correctly describes their character in the country, because the neighborhoods were previously organized in the same way in the cities. A certain number of courtyards / houses were always grouped together to form a neighborhood (e.g. house numbers 100-130 or similar). The entry into the neighborhood took place with the marriage - for men and women, however, originally usually separated according to sex. Only the German-Saxon residents of a locality were permitted.

According to old tradition, the neighborhoods had their own statutes and neighborhood rules, which were strictly adhered to. Offenses (such as not showing up at a funeral) were punished and had to be paid for with fines or in kind. Being violated by a neighborhood or willfully revolting against the rules could ultimately have serious consequences for unadjusted individuals, because without the help of the neighborhood many hard work would not be possible and social life outside the community hardly existed.

In return, the neighborhoods in the villages took on many social tasks, but also things that would nowadays be assigned to municipal or state bodies. There was neighborhood work such as building a house together, clearing the forest, felling wood, working on the church or other infrastructure work. The social tasks included a. preparing and holding funerals and weddings together.

The neighborhoods held execution days at certain intervals (usually once a year) on which internal matters were clarified, penalties were imposed or new members were accepted. Each neighborhood was headed by an elected neighbor father (for the men) and a neighbor mother (for the women). The neighborhood organized itself. In addition, it regulated and made life easier for the individual.

Neighborhood property included the neighborhood books (which kept records of the neighborhood's monies and purchases), neighborhood items, a cash register and movable material goods such as large quantities of crockery and cutlery (for weddings) or a death bank for funerals. The statutes and the neighborhood treasury, which was fed by contributions, fines and donations, were kept in the neighborhood shop - wooden chests, often painted or decorated with inlay.

In addition to fulfilling duties, the neighborhoods were also used for regular entertainment.

Customs and norms

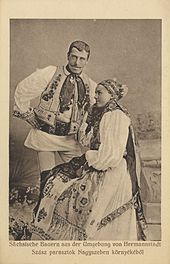

The customs and norms of the Transylvanian Saxons were comparatively conservative, which, however, is understandable from their deliberate delimitation from the other ethnic groups in Transylvania. The cohesion of the community and the survival of the ethnic group, even in adverse times, were only possible through strict rules and observance of customs. Before the great emigration, marriages with other ethnic groups were one of the greatest taboos. This was seen as undermining the cohesion of the ethnic group and was often answered with the exclusion and stigmatization of the people concerned and their children.

Until the beginning of the 1990s, the majority of the Transylvanian-Saxon population lived in the village. The urban centers were important, as the educational institutions and a large part of the workplaces were located there, but the Transylvanian-Saxon population was largely rural right up to the end. Up until the Second World War (and in some cases long afterwards), old traditions were still alive in the villages and were upheld. This cultural formation and the cohesion of these communities were remarkable and contributed to a large extent to the fact that the Transylvanian Saxons were able to maintain themselves as an ethnic group for 850 years.

Courtyard and village structure

One of the special features of the Transylvanian-Saxon villages is their planned layout. The villages did not grow organically in all directions, but according to fixed rules. Villages, towns and market towns were planned during the settlement period and during inland settlement. The Hattert (Transylvanian-Saxon for district) of the municipality was marked out. The Hattert could be up to 35 km² or more.

The Saxon villages are basically street or elongated village villages . The gable side of the houses faces the street; there are very few exceptions - especially in Nösnerland , where the long side of the houses faces the street. The plots are directly adjacent to each other. So it was not possible to extend the property of a farm because this would have been at the expense of the neighbors. Therefore, in most of the villages, the plot of land, including size and shape, has remained unchanged since the settlement period. There are high brick gates between the house and the neighboring house. So it follows the entrance to the house, etc. The street sides are bordered by continuous house fronts. This design creates the very closed impression of the Saxon villages. The courtyards are usually three or four times as long as they are wide in their typical elongated shape. Here, the arrangement of the building (off the road): House, cropping (tool shed), stables and, across to the house, parallel to the gate to the barn. Behind it are the gardens (just as elongated). The plots can be 50 to 100 meters long, but only take up a fraction of the width.

The plots within the settlement were originally distributed by lot. According to old Saxon law, the yard (generally the development) of a property belonged to the building person or their heirs, according to old custom it was always the youngest child who was responsible for looking after the aged parents. However, the land on which the buildings stood still belonged to the community. If the residents died without heirs or died in some other way (in the time of the Turkish wars through fighting or deportation) or if they left the place and the house fell into disrepair, the farm was withdrawn from the community and re-assigned. The same applied to orchards and vineyards: if they were no longer worked by the owner and remained desolate, someone else could - after a certain period of time - take care of these properties and claim them for himself. The original owner, even if he reappeared, had forfeited all rights to his old property after this type of statute of limitations. Only later did the practice change and the farms became private property and vineyards became private property.

The same was true for the parcels on which arable farming was carried out. The parcels belonged to the community (and not the farmers who worked them) and were raffled off at regular intervals among the existing residents. This meant that with an increasing population the flurry requirement applied. If there was not enough land for the residents, new tubs (parcels of land) were removed from the community soil (the community's land holdings) and released for agricultural use and raffled off. If this tub had to be cleared first, this was done in teamwork - for the benefit of all.

This self-regulating system was very egalitarian and flexible - it was only abolished by Habsburg legislation.

history

12-14 century

From 1147 onwards, a significant number of German settlers probably came to the region - but these were not demonstrably the first there. In the middle of the 12th century, Geisa II , King of Hungary , had extended his sphere of influence over the whole of Transylvania to the Carpathian Ridge and had the German settlers open up the initially very sparsely populated area.

So that the settlements could develop quickly and generate appropriate tax profits for the state, he gave the settlers, like the Szekler auxiliary people , special rights. In it they were initially assured various privileges ( freedoms ) and granted certain tax and economic advantages . These rights were codified in 1224 in the Golden Charter (Andreanum) under Andreas II. In addition to the free use of waters and forests and the freedom from customs duties for German traders, the settlers were also subject to neither the nobility nor the church and thus free citizens (in the sense of the then Understanding of active citizens , i.e. male, tax-paying and adult).

The young settlements developed rapidly. The population rose rapidly due to immigration and birth surpluses, but was decimated considerably by the Mongol storm of 1241. The country was set back in its development. In some settlements, only two to three generations had lived before they were devastated by the attacks of the Mongolian horsemen. However, the recovery took place relatively quickly, and inland settlement regained momentum. After the country was built in the 12th and 13th centuries, a long phase of prosperity followed. The first period of great cultural and economic prosperity of the Transylvanian Saxons can therefore also be found in the 14th and 15th centuries. The population of the Seven Chairs and the other districts of the Königsboden grew rapidly and steadily. Gold, silver and salt were mined in the mines of the Forest Carpathians and in the Rodna Mountains . Trade flourished and the economy flourished. The routes of the Saxon traders ranged from Danzig on the Baltic Sea via Krakow , Vienna , Belgrade to Constantinople and Crimea . Until 1395 (the first Turkish invasion) there were no major external threats, and the upswing of German settlements now also led to the formation of real urban centers. Sibiu , Kronstadt , Klausenburg , Bistritz , Schäßburg and Mühlbach became towns, other places like Agnetheln , Broos , Biertan , Marktschelken , Mediasch and Sächsisch-Regen became market towns . The craft was already diversified. In the oldest surviving guild regulations of the Seven Chairs from 1376, 19 guilds and 25 trades are noted. From the middle of the 15th century, the cities of the royal soil (especially Kronstadt) had become so financially strong that they lent money to the Hungarian king in exchange for pledging entire towns.

15-17 century

Regardless of the flowering inside, for the first time since the end of the 14th century there was again a danger from outside. After the Turks conquered Anatolia in 1350 and defeated the Crusader army at Nicopolis in 1396 , their eyes turned to the Kingdom of Hungary and its prosperous Eastern Province. The wealth of medieval Transylvania and its proximity to the Ottoman Empire made it the target of dozens of Turkish incursions with arson , kidnapping , murder and the devastation of entire regions from the 15th century onwards .

In order to react to the growing threat from the Turks, Szekler , the Hungarian nobility and the Saxons formed a three-nation union (Unio trium nationum) in 1437 in order to take action against the Turks. In 1479 the Union won a great victory on the Brodfeld near Mühlbach in the Unterwald (see also Battle on the Brodfeld ).

Yet the military threat was omnipresent. The looting trains of the Ottoman cavalry armies, who acted as runners and burners , were like constant pinpricks. The usual procedure was as follows: Small horse troops without any entourage quickly penetrated the interior of the country via mountain paths, set the villages on fire, stole cattle and people and then disappeared again by the shortest route. At the borders, the prisoners were offered for a large ransom. Anyone who was not ransomed became slavery. Against this approach, the Transylvanian Saxons built the churches in the villages and market towns into defensive structures . The sacred buildings were provided with circular walls and defensive towers and were intended to offer the population protection and refuge in emergency situations. In some cases, fortifications were bought and expanded by aristocrats (as in Kelling ). In some places, large farm castles (for example in Reps , Keisd , Michelsberg and Rosenau ) or strategically planned pass fortresses such as in Stolzenburg or Törzburg , which were supposed to secure control of important trade and military routes, were built on conveniently located mountain ridges . The cities were also heavily fortified and in some cases provided with several defensive rings. In this way, a network of fortified fortified churches and towns was created that is unique in Europe .

In the large-scale Ottoman raids, however, these measures were only of limited use. Only the great fortified churches and the cities could resist a real army. Tens of thousands of prisoners (from the Seven Chairs alone ) were regularly taken away , i. H. abducted to Turkey, which demanded a huge blood toll from the relatively small ethnic group. In this way, some villages were definitively abandoned settlements (known examples are Underten and fat village in South Transylvania), others were also, in part, on several occasions, repopulated. The people needed for this were partly Saxon residents of the county estates (there were also German settlements on the soil of Hungarian nobles who did not have the right to the Golden Charter), partly Szeklers who moved into the Repser Stuhl from the east, or Romanians from outside the royal soil . The loss of people in the Brooser and Mühlbacher chair was particularly great. In many villages, secondary settlement rights (a kind of license to settle in Saxon villages on the Königsboden) were granted to Romanians because there was simply no Saxon population left to fill the gaps. In the Brooser Stuhl, almost the entire population was carried away in one fell swoop during a Turkish raid at the beginning of the 15th century, so that the places there remained desolate for years. Something similar happened several times with the city of Mühlbach.

The Turks decided not to incorporate Transylvania into territory. In 1529 the Ottomans reached Vienna and devastated all of Hungary on their train. After that the Hungarian Empire split into three parts. The western part went to Habsburg. The rest of Hungary was ruled by the Turks for 150 years. Transylvania remained an independent principality under Ottoman suzerainty, but it was subject to tribute. Regardless, the Turkish raids and looting regularly devastated the country up to the beginning of the 18th century.

18. – 19. century

At the end of the 17th century, Transylvania came under Habsburg rule and became crown land .

About a century later, at the end of the 18th century, in the course of his "Revolution from Above" , Emperor Joseph II declared all rights set out in the Golden Charter to be null and void. The state constitution of the University of Nations and the centuries-old autonomy of the royal soil were repealed. Shortly before his death, however, he reversed the reforms .

In 1848 the Vienna March Revolution spread to Transylvania. The Hungarian insurgents occupied Transylvania and tried again to abolish the autonomy of the Saxons. With Russian help , Austria succeeded in 1849 in defeating the Hungarian revolutionaries and recapturing Transylvania. The old rights were temporarily restored.

As a result of the Austro-Hungarian Compromise , Transylvania fell to Hungary in 1867, after which the University of Nations was finally abolished as a self-governing body. The Hungarian state subsequently took numerous measures to Magyarize the various minorities in the national territory. Of all the German-speaking minorities, the Transylvanian Saxons were most likely to resist these efforts through a strong social and cultural cohesion, as well as the independent basis of their educational institutions, the foundation heritage of the Nations University. The Protestant regional church of the Transylvanian Saxons , which was closely linked to the German school system, turned out to be the institution with the strongest integrative capabilities . Since 1722 there was general compulsory schooling for boys and girls. In addition, various social associations such as sister, brother and neighborhood as well as the solid economic basis of the minority made a decisive contribution to delimiting the community of Transylvanian Saxons from the outside and to consolidating it internally.

Student fraternities from Transylvanian Saxony were the Corps Normannia Halle , the Tübingen Corps Transsylvania, the Corps Saxonia Vienna and the Wiener Landsmannschaft Bukowina .

20th century

Prediction of inner development

In 1865 the report of the Englishman Charles Boner , who had traveled to Transylvania, appeared and one could read (in German 1868): “But how is it that these German settlers… disappear like that instead of populating the country with their descendants? ... There are villages in which the population has remained stationary for a hundred and more years. In others, which were originally inhabited by nothing but Germans,… you can hardly find a Saxon these days; the whole population is Romanian. ... This change has taken place completely from the childhood of people still alive until today. ... Even from the pulpit, the difficult and delicate subject was dealt with very emphatically and with great eloquence. ... All over the country, the Saxons, who used to be first, are gradually being pushed back into second. "

Twenty years later a German traveler wrote about Transylvania: “The Saxons complain, often sighing, that their villages are dying out, that their houses are empty and that Romanians are sitting in them. 'Can we do it for it,' reply the Romanians, have we killed the Saxons, are we doing them harm? Certainly not, it is their own fault if they disappear and leave no offspring. '"

In 1912 the situation had already changed so much that a lecture on “Extermination and repression in the struggle for life of the Saxon people” was heard at the “Association for Transylvanian Regional Studies”: “The scale is sinking more and more in favor of the Romanians. … In political terms, reference only needs to be made to the possibility of universal equal suffrage in order to mark the probable future. … What we are seeing here is displacement taking place with the force of a force of nature. ”In 1931 Heinrich Siegmund published the book Deutsche-Dämmerung in Siebenbürgen . Although it had no noteworthy political impact, it foresaw future developments.

Greater Romania

At the end of the First World War , Transylvania was assigned to the Kingdom of Romania , especially through the commitment of the Romanians there . The Transylvanian Saxons and the other Germans in the region supported this cause, because they expected better minority legislation from a new Greater Romania . However, the Bucharest government soon continued and even tightened the anti-minority policies known from the Hungarian era. The University of Nations was expropriated in 1921 and finally dissolved in 1937.

Nevertheless, the Saxon population, which was already in the minority in relation to Hungarians and Romanians - even on the royal soil - before 1918 , had reached a final demographic high point. At the end of the 1930s the population had risen to almost 300,000 people, returning to the level of the late Middle Ages. Economically, too, the community found itself in a phase of highest economic potential, which was characterized by robust growth and high innovative strength.

Due to the democratic constitution of the Romanian state at the time, it was also possible for the Transylvanian Saxons to make their community heard and present. There were also a large number of own organizations, such as associations and foundations as well as independent German-speaking media. The diversity of the latter was remarkable - in 1930 alone around 60 German-language periodicals were published in Transylvania. Nevertheless, marginalization tendencies in the public administration, which were to increase many times over in the post-war years, began during this time.

Second World War

During the time of National Socialism , especially from 1943, the Transylvanian Saxons, like all other Romanian Germans as ethnic Germans , were involved in the politics of the German Reich from 1933 to 1945 .

In 1940 there was an upheaval within Transylvania that at first appeared dramatic, but this was to be exceeded by the consequences of the war. Northern Transylvania was separated from Central and Southern Transylvania by the 2nd Vienna Arbitration and, together with the Szekler regions, was added to Hungary. For the first time in their history, the Transylvanian Saxons found themselves in two different states.

Northern Transylvania was now an area of the Volksbund der Deutschen in Hungary . In Southern Transylvania led by the German government was German ethnic group set up, all the cultural, political and economic organizations by rich German model equal switched . A large part of the Transylvanian Saxons fit for military service also served in German front-line units. This was an - officially - voluntary matter, which, however, was made very effective by internal pressure from the German ethnic group . For northern Transylvania there was a special agreement between the Hungarian state and the imperial government, which provided for the drafting of ethnic German recruits into the German armed forces .

Around 95% of the able-bodied Romanian Germans served in the front units of the Waffen SS (around 63,000 people), while some came to units with police functions such as the SD Sonderkommandos , of which at least 2,000 belonged to concentration camp guard companies, of which at least 55% were in an extermination camp (mainly Auschwitz and Lublin) have served. About 15% of the Romanian Germans serving in the Waffen-SS died in the war, but only a few thousand of the survivors returned to Romania.

Romania's move to the Allied side on August 23, 1944 was described by the German population as a collapse . The far-reaching consequences of this event called the existence of the entire ethnic group into question. It was the beginning of the end of the Transylvanian Saxon community, so to speak.

When the front advanced to northern Transylvania, the German general Artur Phleps ordered the evacuation of the Germans from the Nösnerland , the Reener Ländchen and some villages around Zendersch and Rode , in southern Transylvania. Since these regions still belonged to Hungary, which was allied with Germany, the forced evacuations could be enforced with military pressure from the Wehrmacht. In the Romanian part of Transylvania, however, no evacuation measures took place.

On September 7th, the escape from the Soviet troops began. The German population was transported away from the cities of Bistritz and Sächsisch-Regen by Wehrmacht trains and trucks. From September 9th, the inhabitants of the German villages set out on long treks towards the imperial border. Most of them ended up in Austria, a few were able to escape to Germany and the small remainder, who did not succeed, were overwhelmed by the events of the war and transported back to Transylvania. Of 298,000 Germans living in Transylvania in 1941, around 50,000 had already disappeared during the war.

post war period

At the beginning of 1945 the deportation of about 30,000 Transylvanian Saxons to the Ukrainian SSR ( Donets Basin ) and other areas as far as the Urals began for forced labor . All men between 17 and 45 who had not been drafted and all women between 18 and 35 were “dug up”. The losses were considerable. The remaining Germans were totally expropriated, temporarily deprived of their rights (until 1956, voting rights again from 1950) and were exposed to state discrimination and severe repression .

Since the private means of production were nationalized in all of Romania (June 11, 1948), the German minority was also affected by this measure, but earlier and much more ruthlessly and tougher than the rest of the population. From 1946 onwards, all agricultural land (fields, meadows, vineyards) were expropriated from the Saxon population and handed over to Romanians (these possessions, however, had to give up those properties again with the emergence of the collective farm until the end of the 1950s). In addition, the agricultural implements and a large part of the stocks (grain, wine) and livestock (pigs, cattle, etc.) were expropriated and given to Romanian colonists from the Old Kingdom. The same thing happened in the villages with many Saxon courts, in the cities with the houses and apartments, the shops and businesses, including the interior. After 1956, some of the confiscated German houses, especially in the smaller communities, were returned to the rightful owners - in return, however, they had to join the collective of the now communist-controlled farms. The church property (meaning church property, forests, real estate such as school buildings - only the church buildings themselves were excluded) was nationalized, as were the German schools, which were previously under the control of the Evangelical Church AB. In addition, all German daily and weekly newspapers had to be discontinued.

All the factories, machines, shops, fields, forests, vineyards, undeveloped land, countless real estate, the savings associations and insurance companies (with their deposits) that were owned by the Transylvanian Saxons, as well as the two large credit institutions of the German minority ( Kronstädter Sparkasse and Hermannstädter Sparkassa ) was incorporated into the Romanian state. In this way, the Transylvanian Saxons were not only robbed of their property and rights, but the livelihood of the ethnic group was permanently destroyed. In the cultural field, the show trials in the second half of the 1950s (such as the Kronstadt writers ' trial and the black church trial ) put the Transylvanian Saxons under pressure. All of these were also reasons for the later often voluntary departure.

At the end of the 1950s, family reunification began with the Transylvanian Saxons who were already living in Germany . A never-ending chain of emigration emerged, which has grown into a real wave of emigration since the mid-1970s. From 1969 an agreement between Romania and the Federal Republic of Germany ensured a continuous flow of people of German nationality from Romania. The plan was to have the “transfer” of the German population completed in 2007. The West German state bought the Germans from the Romanian state for around 10,000 DM per person. In addition, those willing to emigrate were forced to surrender their property (in particular residential property and land) to the state and thus have the communist state compulsorily compensate them with a small amount of money that was far below the normally achievable price. In addition, money was also asked for giving up Romanian citizenship. So the state earned several times from the emigrants.

In addition, the forced settlement of Romanians from the Old Reich ( Moldavia and Wallachia ) meant that the Transylvanian Saxons in their traditional areas fell behind in numbers and were increasingly marginalized. In addition, a latent attitude towards discrimination on the part of the state authorities meant that official positions were always filled with Romanians and German-speaking applicants had significantly reduced opportunities for professional advancement. There were no explicit minority rights. An exception was the school system, where German-language lessons were tolerated, but increasingly pushed back there, since more and more subjects and exams had to be held in Romanian. All of these measures aimed at a creeping assimilation of the German-speaking Transylvanian Saxons and were probably one of the reasons for the wave of emigration after the border was opened in 1989.

Since 1989

In 1989 there were still around 115,000 Transylvanian Saxons in Transylvania. Of these, more than 90,000 left the country within two years, from 1990 to 1992. The number of the German minority in Transylvania finally fell to below 20,000 at the end of the 1990s. Valuable historical buildings / villages are increasingly falling into disrepair. The emigration shock subsided slowly in the following years.

The Transylvanian Saxons and other German-speaking groups in what is now Romania have been represented by the Democratic Forum of Germans in Romania (DFDR) since the democratization of Romania and thus have a political interest group in Romania for the first time since the prewar period. Worldwide there are interest groups in Germany ( Association of Transylvanian Saxons in Germany eV), in Austria (Federal Association of Transylvanian Saxons in Austria), in Canada (Landsmannschaft der Transylvanian Saxons in Canada) and the USA (Alliance of Transylvanian Saxons in the USA) are united in a federation of the Transylvanian Saxons .

In the local elections in 2000, but especially in those in 2004, it became clear that, despite the emigration of the majority of their population, the Transylvanian Saxons managed to regain importance on the political and administrative level in the Sibiu district and become a not insignificant public factor To become of life. In addition to the President of Romania ( Klaus Johannis ) and the Mayor of Heltau (Johann Krech), the DFDR also provides the district council chairman of the Sibiu district ( Martin Bottesch ).

Transylvanian Saxony as a community in today's Transylvania

While the Transylvanian Saxons saw themselves in the course of history until the fall of the Wall in 1989 as a strong community with a high level of integration for the individual members, who were able to successfully defend themselves against assimilation , the self-image of those who remained in Transylvania is now extremely controversial .

95% of the Saxon population have left the country, the rest are over-aged (the average age is now around 60) and the few younger people can no longer find partners among their own kind. This paves the way for assimilation, which has been prevented for a long time, and calls the community itself more and more into question, especially since many entrances to the Protestant parishes (which do exist) are Romanians or children from mixed marriages.

Although emigration has now completely subsided, many more old people die than children are born every year. It is more than questionable whether the emigrants will return in significant numbers in order to enable the community to undergo a new demographic upswing.

However, it cannot be overlooked that the community has recovered from the emigration shock, is regaining importance and is on an upward trend. However, this applies almost exclusively to the urban parishes, which in some cases even grow through births, immigration or entry into the local parishes. In most of the villages, on the other hand, there are no Saxons under the age of 60 and therefore no prospect of reactivation or the creation of new structures. There the district consistory of the Protestant regional church is concerned with "processing". Buildings are sold or rented, churches rededicated or structurally secured after the valuables and altars of the communities to be dissolved have been transferred to the archives and storage facilities in Sibiu, Medias, Schäßburg or Kronstadt.

In 2007, 13,927 parishioners in 246 parishes belonged to the church districts of Mühlbach , Hermannstadt , Mediasch , Schäßburg and Kronstadt of the Evangelical Church AB in Romania , although this does not reflect the exact number of Transylvanian Saxons still in Transylvania. Those who have left the church are not recorded in the surveys of the Protestant regional church, but the Protestants from the capital Bucharest are. Only the “number of souls” of the parish concerned is given, ie the number of church members. There are larger communities with more than 200 members in cities without exception (Hermannstadt 1427, Kronstadt 1089, Bucharest 972, Mediasch 855, Schäßburg 515, Zeiden 463, Heltau 366, Fogarasch 313, Bistritz 287, Sächsisch-Regen 270, Bartholomae (district of Kronstadt ) 215). In 2016, around 13,000 Transylvanians living in Romania were named Saxons.

The most prominent Transylvanian Saxon in Romania at the moment is Klaus Johannis , the incumbent state president and long-time mayor of Sibiu. The DFDR also holds other mayor posts in Transylvania ( Heltau , Freck ). In the 2008 local elections, Klaus Johannis and district council chairman Martin Bottesch were confirmed in office. There are municipal councils or city councils of the DFDR in Transylvania in addition to the places mentioned in Kerz , Reps , Zeiden and Bodendorf . In Medias , a Transylvanian-Saxon mayor - and a former candidate of the DFDR - was re-elected ( Daniel Thellmann ), who, however, had converted to the Romanian Democratic-Liberal Party (PDL) shortly before the election . In the district of Sibiu the most important political posts (chairman of the district council, mayor of the largest cities) are held by members of the German minority.

Transylvanian Saxons outside Transylvania

In Germany, Austria, Canada and the USA, the Transylvanian Saxons are represented by national associations which, together with the DFDR, are part of the global Federation of Transylvanian Saxons . The chairman of the federation is Bernd Fabritius . Federal chairwoman of the Association of Transylvanian Saxons in Germany V. has been Herta Daniel since 2015 . The headquarters of the federal and federation offices are in Munich. Local museums of the Transylvanian Saxons living in Germany are located in u. a. in Gundelsheim and Wiehl-Drabenderhöhe in the Oberbergischer Kreis.

religion

The Transylvanian Saxons have been Protestant since the Reformation through Honterus . To this day they have their own bishop who heads the Evangelical Church AB in Romania . Christoph Michael Klein was Bishop of Saxony until October 2010 and one of the last great figures of integration in the shrunken community. Reinhart Guib followed him on December 12, 2010 .

language

Transylvanian-Saxon is a predominantly Moselle-Franconian relict dialect, partly on the level of development of Middle High German . It is one of the oldest surviving German settler languages, which emerged from the 12th century as a compensatory dialect of various dialects and has preserved many medieval forms and idioms , with West Central German elements clearly predominating. The closest related dialects are Riparian and Luxembourgish .

The contact with Hungarians ( Szeklern ) and Romanians mediated influences from these languages for centuries. From the 16th century onwards, however, the Reformation and the language of the Luther Bible had a stronger influence , making New High German the written language of the Transylvanian Saxons. In the spoken language, i.e. in the private sphere, the Transylvanian-Saxon dialect always dominated, both in the villages of Transylvania and in the urban centers such as Kronstadt , Sibiu , Schäßburg and Bistritz .

The written and school language in Transylvania has always been Latin. Only through the Reformation did (standard) German gain in importance. However, the religious language of preaching in the villages remained Saxon until the late 19th century. Unlike in other regions, the dialect was not limited to private language domains , but was spoken by all strata of the Saxon population, albeit in many different village dialects, some of which can be clearly distinguished from one another. In the bourgeois circles of the Saxon cities, however, a more polished urban Saxon developed, which replaced many traditional words with standard German terms. In the 18th and 19th centuries, when Transylvania was part of the Habsburg Empire, there was a relatively strong Austrian influence. Numerous words and the pronunciation of terms adopted at the time resemble the Viennese German of that time. Due to the mass emigration to West Germany before and after the revolution, which means that practically all Saxons who remained in the state now have relatives in Germany, the linguistic influence has recently come mainly from there.

music

The Transylvanian songs contain texts in both German and Saxon. For example, the hymn Transylvania Land of Blessings was written in German, others, such as Motterharz tea Adelstin (Mutterherz, du Edelstein), in Saxon. Most of the Saxon songs are played in 3/4 time . The texts are mostly about work, village life, home, nature experiences or love and loyalty. Well-known examples would be Det Medche vun Urbichen (The girl from Urwegen), Of der Goaß, do stiht an Bunk (On the street, there is a bank), Af deser Ierd (On this earth) or Äm Hontertstrooch (In Holderstrauch).

Critical or political statements are remarkably small. By the end of the second wave of emigration these songs were in the regularly held festivals (. Eg for crown fixed on Peter and Paul but also weddings and neighborhoods ) together, usually sung without accompaniment. At funerals, the mourners were often accompanied to the cemetery by musicians from the local brass bands, the adjuvants .

Authors

- Ursula Ackrill : Zeiden, in January

- Wolf of Aichelburg

- Hans Bergel : dance in chains , when the eagles come , faces of a landscape

- Gustav Gräser : Erdsternzeit , Tao (Nachdichtung) , poems of the wanderer

- Karin Gündisch : Far, behind the woods , In the land of chocolate and bananas , Paradise is in America

- Josef Haltrich : German folk tales from the Sachsenland in Transylvania

- Georg Maurer

- Adolf Meschendörfer : The city in the east , the buffalo fountain

- Oskar Pastior , Georg Büchner Prize (2006)

- Oskar Paulini

- Stephan Ludwig Roth

- Georg Scherg

- Eginald Schlattner : The beheaded rooster , red gloves , the piano in the fog

- Dieter Schlesak : Capesius, the Auschwitz pharmacist , Fatherland Days , White Region

- Paul Schuster : Five liters of Zuika

- Walther Gottfried Seidner : On cloud seven, guarantors… paradise in hell… good night stories.

- Gertrud Stephani-Klein

- Erwin Wittstock

- Joachim Wittstock

- Iris Wolff : Half a stone , luminous shadows

- Heinrich Zillich

literature

history

- Carl Göllner : The Transylvanian Saxons in the Revolutionary Years 1848–1849. Editura Academiei RSR, Bucharest 1967.

- Carl Göllner: History of the Germans in the area of Romania. Volume 1: 12th century - 1848. Kriterion Verlag, Bucharest 1979, DNB 800275470 .

- Carl Göllner: Siebenburg-Saxon personalities; Portraits. Editura Politică, Bucharest 1981.

- Gernot Nussbächer: From documents and chronicles - contributions to the Transylvanian local history. Second volume. Kriterion Verlag, Bucharest 1985.

- Ernst Wagner : History of the Transylvanian Saxons. Wort und Welt Verlag, Thaur near Innsbruck 1990.

- Carl Göllner: The Transylvanian Saxons in the years 1848–1918. Böhlau, Cologne 1998.

- Georg Weber among others: The deportation of Transylvanian Saxons to the Soviet Union 1945–1949. Volume 1: The deportation as a historical event ; Volume 2: The deportation as a geographical event. Volume 3: Sources and Images . Böhlau Verlag, Cologne 1995.

- Konrad Gündisch: Transylvania and the Transylvanian Saxons . Verlag Langen Müller, Munich 1998, ISBN 3-7844-2685-9 .

- Paul Milata : Between Hitler, Stalin and Antonescu. Romanian Germans in the Waffen SS. Böhlau, Cologne et al. 2007.

- Wilhelm Andreas Baumgärtner: The forgotten way. How the Saxons came to Transylvania. Hora, Sibiu 2007.

- Wilhelm Andreas Baumgärtner: A world on the move. The Transylvanian Saxons in the late Middle Ages. Schiller, Hermannstadt / Bonn 2008.

- Heinz Günther Hüsch, Hannelore Baier, Dietmar Leber: Paths to Freedom - German-Romanian Documents on Family Reunification and Resettlement 1968–1989. Aachen / Munich / Neuss 2016, ISBN 978-3-934794-44-3 .

Cultural history

- Michaela Nowotnick: Autumn over Transylvania. Farewell to the culture of the Romanian Germans. In: NZZ. December 30th, 2016. (online)

- Carl Göllner: witch trials in Transylvania. Editura Dacia, Cluj 1971.

- Carl Göllner: Transylvanian cities in the Middle Ages. Ed. Științifică, Bucharest 1971.

- Irina Livezeanu: Cultura si nationalism în România Mare 1918–1930. (Culture and Nationalism in Greater Romania). Humanitas, Bucharest 1998.

- Gudrun-Liane Ittu: Cultura germanilor din România în perioada 1944–1989 (The culture of the Germans in Romania in the period 1944–1988). Sibiu, Lucian Blaga 2004.

- Wim van der Kallen, Henrik Lungagnini: Transylvania. A thousand years of European culture. Weltbild Verlag, Augsburg 2008, ISBN 978-3-8289-0828-4 .

Literary studies

- Michaela Nowotnick: The inescapability of biography. The novel “Red Gloves” by Eginald Schlattner as a case study on Romanian German literature. Böhlau, Cologne / Weimar / Vienna 2016, ISBN 978-3-412-50344-4 .

Visual arts

- Victor Roth: History of German sculpture in Transylvania. Strasbourg 1906.

- Victor Roth: German art in Transylvania. Berlin / Hermannstadt 1934.

- Julius Bielz : portrait catalog of the Transylvanian Saxons . Hamburg 1936.

- Otto Folberth : Gothic in Transylvania. the master of the Medias Altar and his time. Verlag Anton Schroll, Vienna / Munich 1973, ISBN 3-7031-0358-2 .

- Gustav Gündisch, Albert Klein , Harald Krasser and others: Studies on the history of art in Transylvania. Kriterion Verlag, Bucharest 1976.

- Brigitte Stephani: On Transylvanian-German art. An attempt at an introduction (I and II). In: New Literature. Bucharest 1982/1, pp. 70-83 and 1982/2, pp. 93-103.

- Brigitte Stephani (Ed.): They shaped our art. Studies and essays. Dacia Publishing House, Cluj Napoca 1985.

- Jürgen Kolbe, Walter Biemel: ways of Transylvanian artists. Painting and sculpture. Hirmer Verlag, Munich 1988.

- Viorica Guy Marica: Arta germana din Transilvania (German art in Transylvania). In: Steaua. (Klausenburg-Napoca), Vol. XLV, Issue 6, 1994.

- Doina Udrescu: German art from Transylvania in the collections of the Brukenthal Museum in Sibiu (1800–1950). DFDR publishing house, Hermannstadt 2003, ISBN 973-0-02900-8 .

architecture

- Victor Roth: History of German Architecture in Transylvania. Strasbourg 1905.

- Emil Sigerus : Transylvanian-Saxon castles and church forts. Verlag Josef Drotleff, Sibiu 1900.

- Paul Niedermaier: Transylvanian cities. Böhlau, Cologne 1977.

Folklore

- Georg Adolf Schullerus: village home. Life pictures. W. Krafft Verlag, Hermannstadt 1908.

- Julius Bielz: The national costume of the Transylvanian Saxons. Meridians, Bucharest 1956. (Romanian)

- Emil Sigerus : Folklore and art historical writings. Edited by Brigitte Stephani. Kriterion Verlag, Bucharest 1977.

- Roswith Capesius : The Transylvanian-Saxon Farmhouse. Home decor. Kriterion Verlag, Bucharest 1977.

- Claus Stephani : The stone flowers. Burzenland Saxon sagas and local stories. Ion Creangă Publishing House, Bucharest 1977.

- Claus Stephani: Oaks on the way. Folk tales of the Germans from Romania. Dacia Verlag, Cluj-Napoca 1982. ( members.aon.at )

- Claus Stephani: The golden horn. Saxon legends and local stories from the Nösnerland. Ion Creangă Publishing House, Bucharest 1982.

- Claus Stephani: The sun horses. Folk tales from the Zekescher Land. Ion Creangă Publishing House, Bucharest 1983.

- Ortrun Scola, Gerda Bretz-Schwarzenbacher, Annemarie Schiel: The festive costume of the Transylvanian Saxons. Callwey Verlag, Munich 1987, ISBN 3-7667-0842-2 .

- Claus Stephani: Fairy tales of the Romanian Germans. (= The fairy tales of world literature). Eugen Diederichs Verlag, Munich 1991.

- Claus Stephani: Legends of the Romanian Germans. Eugen Diederichs Verlag, Munich 1994.

- Erhard Antoni, Roswith Capesius, Karl Fisi and others: From the folklore of the Transylvanian Saxons. Honterus Verlag, Hermannstadt 2003.

medicine

- Josif Spielmann, Arnold Huttmann : Sheets from the medical history of the Transylvanian Saxons. In: Grünenthal balance. Volume 7, Issue 2, Aachen 1968.

Web links

- Association of the Transylvanian Saxons in Germany . In: sevenbuerger.de

- Federal Association of the Transylvanian Saxons in Austria . In: 7buerger.at

- Audio Atlas of Transylvanian-Saxon Dialects . In: Ludwig Maximilians University of Munich

- Film recordings from Transylvania from 1945 . onYouTube

- Transylvanian Saxony - yesterday, today, tomorrow. From a permanent castle to an open club

Individual evidence

- ^ Charles Boner: Transylvania. Country and people. Weber, Leipzig 1868, p. 287 f.

- ^ Rudolf Bergner: Transylvania. A representation of the country and the people. Bruckner, Leipzig 1984, p. 212 f.

- ↑ Heinrich Siegmund: Destruction and repression in the life struggle of the Saxon people. In: The Carpathians. 6, 1912, pp. 167-182.

- ^ Heinrich Siegmund: German twilight in Transylvania. Honterus, Sibiu 1931.

- ^ Paul Milata: Between Hitler, Stalin and Antonescu. Romanian Germans in the Waffen SS. Böhlau, Cologne / Weimar / Vienna 2007, ISBN 978-3-412-13806-6 , p. 262.

- ↑ Jan Erich Schulte, Michael Wildt (Ed.): The SS after 1945: Debt narrative, popular myths, European memory discourses. V&R unipress, Göttingen 2018, pp. 384–385.

- ↑ Paul Milata: Motives of Romanian German volunteers to join the Waffen-SS in the Waffen-SS. (= New Research. War in History. Volume 74) ISBN 978-3-657-77383-1 , Verlag Ferdinand Schöningh 2014, pp. 216–217.

- ^ Paul Milata: Between Hitler, Stalin and Antonescu. Romanian Germans in the Waffen SS. Böhlau, Cologne / Weimar / Vienna 2007, ISBN 978-3-412-13806-6 .

- ↑ Hannelore Baier : Why do we make such a fuss? In: ADZ. January 12, 2012. (online)

- ↑ Schäßburger Community Letter 1/2008. ( Memento from May 21, 2011 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Membership numbers of the FCR: March 2008

- ↑ Michaela Nowotnick: Autumn over Transylvania. Farewell to the culture of the Romanian Germans. In: Neue Zürcher Zeitung . December 30, 2016.

- ↑ Overcome the ethnic sound barrier. ( Memento from February 5, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) In: Hermannstädter Zeitung. No. 2085, June 6, 2008.