Tamerlano (Handel)

| Work data | |

|---|---|

| Original title: | Tamerlano |

Title page of the libretto, London 1724 |

|

| Shape: | Opera seria |

| Original language: | Italian |

| Music: | georg Friedrich Handel |

| Libretto : | Nicola Francesco Haym |

| Literary source: | Jacques Pradon , Tamerlano ou La Mort de Bajazet (1675) |

| Premiere: | October 31, 1724 |

| Place of premiere: | King's Theater , Haymarket, London |

| Playing time: | 3 hours |

| Place and time of the action: | Bursa , capital of Bithynia , 1402 |

| people | |

|

|

Tamerlano ( HWV 18) is an opera ( Dramma per musica ) in three acts by Georg Friedrich Händel . It takes up the legends of the Ottoman Sultan Bayezid I , who was captured by the Mongolian general Timur Lenk (1336–1405) in a devastating battle in 1402 and probably committed suicide there. Timur Lenk is also called Tamerlano , in Italian Tamerlano .

Emergence

The premiere of Tamerlano , the first of two Handel operas for the sixth season of the Royal Academy of Music , the so-called First Opera Academy, on October 31, 1724, represents a well-considered political move by the composer with regard to his reputation at the English court. In the following month fell three public holidays, which were particularly important for anti-absolutist circles: on the one hand the birthday of the King of England , Scotland and Ireland William of Orange on November 14th, on the other hand the anniversary of his landing with his Dutch army and the Monarchists on November 5, 1688 in the course of the Glorious Revolution in Brixham , which led to Wilhelm's accession to the throne and the strengthening of parliamentarism , and also the " Guy Fawkes Day " (November 5, 1605), the attempt by some British Catholics, the English Parliament and to kill the Protestant king, James I. For more than twenty years these events were commemorated in England with the performance of Nicholas Rowe's progressive play Tamerlane (1702), directed against the absolutism of Louis XIV , sometimes even in several London theaters at the same time. Handel has certainly not lost his respect with George I by supporting this tradition.

libretto

Nicola Francesco Haym , who in the foreword to the libretto , which is dedicated to the Duke of Rutland , expressly refers to himself as the “editor” of the text, used two older sources as a template for his opera book: first Il Tamerlano (Venice 1711) and later one based on it , but already heavily revised libretto Il Bajazet ( Reggio di Lombardia 1719), both set by Conte Agostino Piovene and each by Francesco Gasparini , which in turn go back to the French play Tamerlano ou La Mort de Bajazet (Paris 1675) by Jacques Pradon .

Haym, who had already worked for Handel many times, does not even refer to the opera libretti mentioned in his foreword, but claims that the love intrigue of his libretto is taken directly from Pradon's play (a rival of Racine ), while the historical events leading to the The coloring for this love drama comes from the writings of the Byzantine historian Dukas , which he wrote in the years after the siege of Constantinople . For the poetry of his play, Pradon had the first Latin translation of this work by Ismael Boulliau , which was published in 1649 by the Royal Printing Works in Paris under the title Ducae Michaelis Historia Byzantina . However, this only gave him the framework for his tragedy: apart from the two main roles, Tamerlan and Bajazet, all other roles are his invention. (Andronico could possibly mean a son of Manuel II , who was Prince of Thessaloniki from 1408 to 1423. ) In this respect, Haym's reference to the historical report by Dukas is superfluous, as all useful historical set pieces are in Pradon's tragedy, and thus also in his original libretti. Presumably it wasn't necessary to convince Handel of the dramatic quality of the material, as the composer had known Pradon's piece for a long time. Alessandro Scarlatti had already composed an opera, Il gran Tamerlano , based on a libretto by Antonio Salvi in 1706 . Salvi had taken his material from French drama, which was certainly easy for him, because he was known to be a great lover of French theater and had extensive experience in converting French-language plays into Italian opera libretti. (Only a few months later, his libretto Rodelinda regina de 'Longobardi from 1710 also gave the impetus for the opera of the same name , which Handel was to bring to the stage in February of the following year. This text book Salvis was based on Pierre Corneille's play Pertharite, roi des Lombards from 1652 The first performance of Scarlatti's Tamerlano in September 1706 in Pratolino , the residence of Prince Ferdinando de 'Medici , may have been attended by Handel, because during this time he was the guest of the prince, from whom he finally also commissioned his own opera composition, Rodrigo , which initiated his successful Italian streak.

Haym initially had the Piovenische Libretto from 1711, which he edited. Handel completed his work on this basis between July 3 and 23, i.e. in less than three weeks. At the end of the autograph he wrote a little prematurely : “Fine dell Opera | comminciata li 3rd di Luglio e finita li 23rd | anno 1724. “If Tamerlano had been performed immediately and had not undergone any further redesign, the opera would have been included in the good average of Handel's stage compositions. In any case, it would not have become the key work that it can be seen today. But Handel was evidently not satisfied with the first draft of his opera, as he made a number of changes in the following two months by cutting out a few things and rewriting important passages. However, all of these changes are only retouching compared to the reworking that he now made:

The Opera Academy had hired a new singer, the tenor Francesco Borosini , who, coming from Vienna , arrived in London at the beginning of September and was scheduled for the role of Bajazet. He was the first great Italian tenor to appear in London and had another advantage for the current production: he had sung the leading role in Gasparini's Il Bajazet in Reggio di Lombardia five years earlier , i.e. experience with the character of Bajazet. He also carried a score of Gasparini's opera with him, which apparently attracted Handel's attention: its libretto (1719), Piovenes' adaptation of his own original from 1711, ends with the suicide of Bajazet. According to Borosini, this unusual ending was his idea at the time. But it was not just the other ending that impressed Handel, but the completely different disposition of the person of Bajazet. As a result, he rewrote a significant part of this role: passages from the 1719 libretto were now incorporated into no fewer than nine scenes of the opera. In addition, Handel wanted to make full use of the vocal possibilities that Borosini offered him - he had a vocal range of two octaves. He composed four new versions of the dungeon scene in the first act, the simplest solution of which was the final one. The most fundamental change, however, was the insertion of the scene of Bajazet's death in the third act. By disregarding the conventional rules of the opera seria and the strict classical balance, Handel was able to eradicate the fundamental error of the early libretto. He let himself be guided by a dramatic escalation of the intrigue and the result is wonderfully flowing and extraordinarily emotional music. Apart from the mad scenes in Orlando (1733) and Hercules (1745), there is nothing comparable in Handel's oeuvre.

Another unusual solution in the heyday of the castrati was that a leading role was written for a tenor. Regarding the cast of the game with the newcomer, the London press commented:

"It is commonly reported this gentleman was never cut out for a Singer."

"It is generally said that this gentleman is not tailored for the profession of singer."

In the minds of Uraufführungs series stood at the side Borosinis with soprano Francesca Cuzzoni and the Old - castrato Francesco Bernardi, known as the " Senesino ," two of the most famous and most expensive singers of the time. Senesino did not claim the title role for himself, it was much too dramatic for that. He preferred to leave this to the less well-known Andrea Pacini, who only gave a brief guest appearance in London in 1724/25, and took on the far more conventional role of Andronico, but ensured that his role received no fewer arias than the Tamerlanos.

Cast of the premiere:

- Tamerlano - Andrea Pacini (old castrato )

- Bajazet - Francesco Borosini ( tenor )

- Asteria - Francesca Cuzzoni ( soprano )

- Andronico - Francesco Bernardi, called " Senesino " (old castrato)

- Irene - Anna Vincenza Dotti ( alto )

- Leone - Giuseppe Maria Boschi ( bass )

In the first season Tamerlano had twelve performances and was then resumed for three evenings on November 13, 1731. In the Hamburg Theater am Gänsemarkt there was soon, on September 27, 1725, a performance as Tamerlan , as usual with new (German) recitatives, which were composed by Johann Philipp Praetorius and set to music by Georg Philipp Telemann . The latter also had the musical direction. In addition, Handel's former student in Hamburg, Cyril Wyche, son of the English ambassador there Sir John Wyche, had composed seven (!) New arias for Bajazet. Praetorius and Telemann also wrote the prologue on the occasion of the wedding of Louis XV. of France with the Polish Princess Maria Leszczyńska , who preceded the performance of the opera. An intermezzo by Telemann is also mentioned in the Hamburg textbook, possibly it was Pimpinone or The Unequal Marriage .

The first modern re-performance as Tamerlan , entirely in German (text version: Anton Rudolf and Herman Roth) took place in Karlsruhe on September 7, 1924 under the direction of Fritz Cortolezis . After that, Tamerlano was staged ten times until the 1980s, before the opera began a breathtaking triumphal march through Europe and North America: from 1980 to 2014 there were 58 new productions.

The first performance of the piece in historical performance practice is thanks to the British conductor and baroque opera researcher Jane Glover . It took place on June 24, 1976 at the Convento di Santa Croce in Batignano with James Bowman in the title role.

action

Historical and literary background

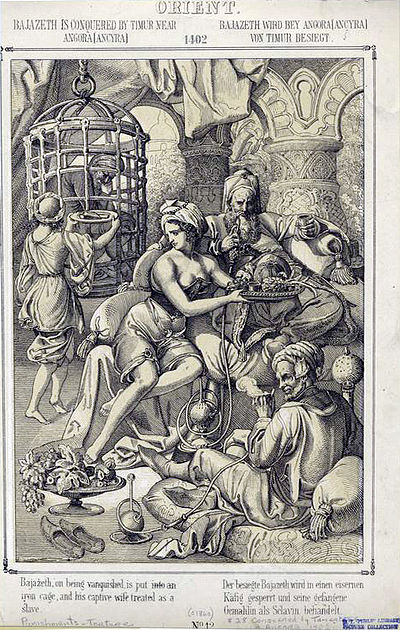

Bayezid I ruled the Ottoman Empire from 1389 to 1402 . Supported by an already established state apparatus, he tried to rule his vast country, which stretched from the Balkans to the Syrian border. His predecessor on the throne, his father Murad I , had interpreted the old law of war chiefs to the effect that he had to claim every enemy prisoner of war. The prisoners were converted to Islam , instructed in Ottoman Turkish and used in the army and administration. In an unmistakable series of wars, Bajazet put down all uprisings in Anatolia and the Balkans, subjugated Bulgaria and besieged Byzantium . Drawing on his power, he was granted the title of sultan by the Cairo resident caliph . Then he moved to Syria . Parts of the country were already occupied by the Ottomans. But a stronger man came from the east, Timur , of the Barlas tribe . Born the son of the head of this Tatar tribe in 1336, Timur was already distinguished by determination and military skills. It can no longer be determined today whether he sustained his serious injury during the disputes in Transoxania or during a mutton theft. In any case, he has been lame since then, which earned him the Persian nickname Lang (the lame), which in Europe became the name Tamerlane. By subjugating rivals, he created a mighty army, which consisted mainly of Turks, in whom the remnants of the earlier Mongolian tribes had merged. In 1379 Timur crossed the Oxus (today: Amudarja ) with the intention of submitting to Persia . Wild atrocities of his hosts, e.g. B. the erection of pyramids and towers from the skulls and bodies of the fallen or murdered warriors, spread horror throughout West Asia and did much to break the resistance or at least to weaken it decisively. In doing so, Timur not only relied on his general skill, but in critical situations he repeatedly entered into negotiations with a section of his opponents who were considered unreliable, which mostly led to the goal and at the decisive moment caused the dropping of large numbers of troops. Timur's life consisted of uninterrupted wars and raids, which in terms of horror are not inferior to those of Genghis Khan , surpass them in many ways and the description of which must appear all the more repulsive as he missed any higher goal. Its effectiveness has no bearing on the further development of human culture in Asia, and many of its moves were only planned and carried out as raids. Between 1379 and 1385 he was able to subdue all of Eastern Persia. From 1385 to 1387 his troops passed through Azerbaijan , Georgia , Armenia and the northern Mesopotamia , murdered tens of thousands of residents and devastated countless cities. He moved across Persia to Mesopotamia and Syria, forced the rulers there to flee or to subjugate and brought all the land to the Mediterranean Sea and the borders of Asia Minor under his control. In order to procure new booty for his armies and probably also in the opinion that he had sufficiently secured the previous conquests, Timur decided to go to India . His advance across the Indus to Delhi was a disaster for the country. Once again financially strengthened by the booty there, Timur decided to fight against the Ottoman Sultan Bajazet I, who had long given him challenging messages. Before that he submitted to Syria. He used the internal contradictions in the Ottoman Empire and made promises to some of the opponents to betray Sultan Bajazet. So he was victorious at Ankara in 1402 , and the Sultan himself fell into his hands. At first, Bajazet was treated passionately in captivity. It can no longer be determined today whether the famous iron cage in which Bajazet was held was a barred sedan chair. After attempting to escape, the sultan had to serve Timur as a footstool. His wife Despina, a Serbian princess, served the victor as cupbearer. Both did not survive the shame and died a year after the defeat. Timur now had the whole of the Middle East in his hand and could feel himself in the safe possession of his gigantic empire, which was hardly inferior in size to that of Genghis Khan.

first act

Courtyard in Tamerlanos Palace, where Bajazet is being held . On Tamerlano's orders, Andronico releases Bajazet from his prison so that he can roam freely around the palace. He asks Andronico for his sword. When Andronico denies him that, he snatches the dagger from a guard and tries to take his own life with it, but is held back by Andronico, who reminds him of Asteria. Bajazet recoils: he would die strong and happy if he didn't have to think about his daughter ( Forte e lieto a morte andrei , No. 3).

Tamerlano gives Andronico his throne back and wants to send him back to Byzantium, but Andronico wants to stay at his court. Tamerlano informs him that he has his eye on Asteria and wants to leave his fiancée Irene Andronico. He demands that Andronico get Asteria's father for his consent in return. If his enemy should tame his anger and alleviate his grief, let him give him peace ( Vo 'dar pace a un alma altiera , No. 4).

Andronico is desperate: He has fallen in love with Asteria and is now supposed to woo her in Tamerlano's name! He hopes that Asteria will forgive him if he fulfills his vassal duty ( Bella Asteria, il tuo cor mi difenda , No. 5). Tamerlano comes to Asteria and explains his plans to her. She is left alone and is disappointed at Andronico's infidelity ( Se non mi vuol amar , no. 7).

Andronico brings Bajazet Tamerlano's request for Asteria's hand. Bajazet is outraged and asks Asteria for her opinion, but remains silent. When Andronico notices her hesitation, he has to admit that he feared her consent to the marriage. Bajazet sends him back to Tamerlano with his negative answer. He does not fear death ( Ciel e terra armi di sdegno , no.8 ).

Andronico is amazed at Asteria's silence. Is she bitter toward him, or does she want to oppose her father? All she asked of him was to carry out her father's orders and not expect anything from her. If she can't get her loved one, she at least wants to be able to hate her enemy ( Deh, lasciatemi il nemico , No. 9).

Portico in Tamerlanos Palace . Andronico receives Irene and reveals Tamerlano's new plans to her. She is angry, whereupon Andronico suggests to her to pretend to be a messenger to Tamerlano and to ask and threaten him. Irene agrees and resolves to change Tamerlano's mind ( Dal crudel che m'ha tradita , No. 10). Andronico is left alone. He laments his fate and swears that he will never be unfaithful to his loved ones ( Benche me sprezzi , no. 12).

Second act

Gallery leading to Tamerlano's room . Tamerlano informs Andronico that his mediation was apparently successful, because Asteria had agreed to marry him. Andronico is amazed. Tamerlano is happy about his own love and the supposed love between Andronico and Irene ( Bella gara che faronno , no. 13).

Andronico meets Asteria. He is amazed at her decision to marry and announces that he will contradict her and declare himself to be Tamerlano's enemy. She is called to Tamerlano and tells Andronico that his complaining is no longer of any use ( Non è più tempo , no. 14). Andronico is left in despair and complains that he cannot find peace with his beloved because fate is against him ( Cerco in vano di placare , no. 16).

The curtain on the room opens. Asteria is sitting there by Tamerlano's side . Irene enters and pretends to be a messenger. She accuses Tamerlano of his infidelity. He justifies himself by saying that the throne she gets to replace is worth no less. Tamerlano leaves, and Asteria mysteriously explains to Irene that she is not seeking the throne or marrying Tamerlano. Irene distrusts her, but at the same time she draws hope ( Par che mi nasce in seno , no. 17).

Bajazet learns from Andronico that Asteria has entered Tamerlano's room. He urges Andronico to follow her together to prevent her accession to the throne. He wanted to pay with his life to bring them to repentance ( A suoi piedi padre esangue , no. 19). Andronico ponders Asteria's falsehood and deceit ( Più d'una tigre altero , no.20 ).

Throne room . Asteria is to ascend the throne at Tamerlano's side. Her mysterious behavior is now cleared up because she intends to kill Tamerlano. It is interrupted by the enraged Bajazet who reproaches his daughter. Moved, Asteria descends from the throne again and explains her failed murder plan. Tamerlano swears revenge, while Asteria and Bajazet happily want to go to their deaths ( Voglio stragi / Eccoti il petto , no. 22). Bajazet ( No, il tuo sdegno mi placò , No. 23), Andronico ( No, che del tuo gran cor , No. 24) and Irene ( No, che sei tanto costante , No. 25) go off one after the other .

Third act

Courtyard in the Seraglio, where Bajazet and Asteria are guarded . Asteria invokes her own loyalty to her father and lover, but is unsure of what is to come ( Cor di padre e cor d'amante , no. 27). Bajazet gives poison to Asteria to “use it bravely”. When the business of vengeance was done, he would follow her into the underworld ( Su la sponda del pigro Lete , No. 27 a, b ).

Tamerlano tells Andronico again to ask Asteria to the throne. Andronico now reveals himself to be unsuitable because he himself loves Asteria. Asteria joins them and confirms her love for Andronico. Tamerlano says that Bajazet should be beheaded and Asteria should be married to the lowest slave. Bajazet is added. Tamerlano now decides that Bajazet and Asteria should serve at his table. Andronico is angry at the humiliation ( A dispetto d'un volto ingrato , no.28 ). Asteria and Andronico declare their love in the face of impending death ( Vivo in te mio caro bene , no. 29).

Tamerlano asks Asteria to give him a mug. Asteria pours the poison into it, but is observed by Irene, who then reveals herself to be Irene and warns Tamerlano. Asteria tries to drink the poison herself, but is prevented from doing so by Andronico. Tamerlano wants to punish her even harder. Bajazet threatens that his spirit will return from the realm of the dead to fight against him ( Empio, per farti guerra , no. 36).

Bajazet leaves and shortly afterwards returns cheerful and reconciled. With his poison he himself chose death. In his agony he calls on the furies to avenge him ( Oh semper avversi Dei ). Asteria wants to follow her father to death and curses the tyrant Tamerlano ( Padre amato, in me riposa , no. 42).

When Andronico also declares that he wants to kill himself, Tamerlano is reconciled by Bajazet's death. Asteria is to be forgiven and he wants to marry Irene. With Andronico he sings about the return of peace and the disappearance of hatred ( Coronata di gigli e di rose , no. 43). The opera ends with a final chorus ( D'atra notte già mirasi a scorno , No. 44).

Short form of the plot

The Tatar ruler Tamerlano defeated the Turkish Sultan Bajazet and took him prisoner. He is engaged to Irene, the Princess of Trebizond, and falls in love with Bajazet's daughter, Asteria. She is devoted to Andronicus, the Greek general and ally Tamerlanos, and is loved again. The almighty ruler asks Andronicus to advertise him at Asteria. In return he promises him the hand of Irene and the restoration of the Byzantine Empire. He also wants to give freedom to the defeated Bajazet, who desperately seeks death over his defeat. Deeply hurt by the advertising of Andronicus, the princess apparently agrees to return Tamerlano's love - to Bajazet's horror. But the princess only intends to get into Tamerlano's vicinity and murder him. The assassination attempt fails, and the furious Tamerlano vows to ruin his father and daughter. But he thinks about it and repeats the offer from the first act. This time Andronicus refuses and confesses his love for Asteria. The angry Tamerlano swears revenge. At the feast, Asteria, degraded to a slave, tries to poison the ruler. The vigilant Irene saves his life. The condemnation of Asteria drives Bajazet to suicide, thereby evading the violence of Tamerlano. In a long monologue, the dying sultan calls on the Furies to take revenge on Tamerlano. But his death brought the ruler to his senses. He forgives, gives Asteria to Andronicus and marries Irene.

music

The recitatives are of particular importance in this opera. The Secco, Accompagnato and Arioso sections that often appear in it are extremely expressive and allow the good arias to take a back seat at times. A special highlight in this regard is the long monologue of the Bajazet in the third act, which precedes his suicide. This scene is a total break with the customs of the opera seria . His violent, almost insane curses and complaints interrupt the otherwise so harmonious flow and fine balance of the music in many places before the melody thread is picked up again. Handel thus harmonizes dramatic intensity on the one hand and the beauty of a voice on the other, and that goes beyond any gimmicky.

The passages in the autograph that were already fully executed but later discarded can be explained by Borosini's arrival in London (see above). Certain multiple versions of individual arias and recitatives go back to the new production in 1731, in which Handel had to take into account the changed cast. A detailed description of the compositional process during the creation of the opera with evidence of the order in which the various alternative versions of individual movements were drafted, as well as a detailed comparison of the individual text bases can be found in John Merrill Knapp (see literature ). Whether the alternative version of the aria by Irene Par che mi nasca in seno later by Johann Christoph Schmidt jun. The instrumentation information corrected in the hand copy (director's score) ("clar. et clarinet. 1 o et 2 do "), according to which the two cornetti required in the autograph should be replaced by clarinets, really goes back to Handel's intentions, is doubtful.

Success & Criticism

"The overture is well known, and retains its favor among the most striking and agreeable of Handel's instrumental productions [...] Many of the Handel's operas offer perhaps more specimens of his fire and learning, but none more pleasing melodies and agreeable effects [...] In the next [Air], Deh lasciati mi , the composer, in compliance with the taste of the times, adheres perhaps somewhat too closely to the text, almost every two bars being in nearly the same meter. It is, however, original and totally different from all the other songs in the opera. "

“The overture is generally known to be one of the most remarkable and pleasant of Handel's instrumentals [...] Many of Handel's operas may offer more examples of his passion and experience, but by no means more pleasing melodies and pleasant effects [...] in the next [Aria], Deh lasciati mi , the composer, paying tribute to the taste of the time, is perhaps a little too close to the text, almost all two bars are in almost the same meter. But that's actually original and very different from all the other arias in the opera. "

“[…] For whereas of his earlier operas, that is to say, those composed by him between the years 1710 and 1728, the merits are so great, that few are able to say which is to be preferred; those composed after that period have so little to recommend them […] In the former class are Radamistus, Otho, Tamerlane, Rodelinda, Alexander, and Admetus, in either of which scarcely an indifferent air occurs […] ”

“[...] while his earlier operas, which means those he composed between 1710 and 1728, were so successful that hardly anyone can say which of them is preferable, there is little to be said for the operas of the later years [ …] The former include Radamistus, Otho, Tamerlane, Rodelinda, Alexander and Admetus; they all hardly contain a single uninteresting piece [...] "

»Handel's" Tamerlano "is one of the first-rate operas that have made it onto the stage."

"'Tamerlano' is one of Handel's most outstanding musical dramaturgical achievements and has lost none of its impact over the centuries in terms of the musical profile, the abundance of great melodies and plastic motif language."

"There are many moments that make" Tamerlano "one of the outstanding masterpieces of baroque opera."

“Here the principal role, that of Bajazet, is given to a tenor, […] This is the first great tenor role in opera. Handel was entirely successful in portraying Bajazet […] ”

“This time the main role, that of Bajazet, is entrusted to a tenor […] It is the first major tenor role in operatic history. Handel succeeded perfectly in characterizing the Bajazet [...] "

“The character of the finale - that is, an elaborate compound piece made up of integrated recitatives, ariosos, and ensembles - is already present in Tamerlano , again showing Handel in the van despite his generally conservative adherence to the Venetian-Neapolitan operational pattern. ”

“An act closure in the sense of the finale - that is, an artful multi-part piece in which recitative, ariosi and ensemble pieces are combined - Handel has already created in 'Tamerlan', which in turn shows that despite his generally conservative adherence to the Venetian-Neapolitan Opera scheme was in the forefront. "

orchestra

Two recorders , two transverse flutes , two oboes , bassoon , two cornetti , strings, basso continuo (violoncello, lute, harpsichord).

Tamerlano was the first opera in which the flautist and oboist Carl Friedrich Weidemann played in Handel's orchestra.

Discography (selection)

- Oryx 4XLC2 (1970): Gwendolyn Killebrew (Tamerlano), Alexander Young (Bajazet), Carole Bogard (Asteria), Sofia Steffan (Andronico), Joanna Simon (Irene), Marius Rintzler (Leone)

- Copenhagen Chamber Orchestra; Gov. John Moriarty

- CBS 13M 37893 (1983): Henri Ledroit (Tamerlano), John Elwes (Bajazet), Mieke van der Sluis (Asteria), René Jacobs (Andronico), Isabelle Poulenard (Irene), Gregory Reinhart (Leone)

- La Grande Écurie et La Chambre du Roy ; Dir. Jean-Claude Malgoire (176 min)

- Erato 2292-45408-2 (1985): Derek Lee Ragin (Tamerlano), Nigel Robson (Bajazet), Nancy Argenta (Asteria), Michael Chance (Andronico), Jane Findlay (Irene), René Schirrer (Leone)

- The English Baroque Soloists ; Dir. John Eliot Gardiner (180 min)

- Naxos / Arthaus 100702 (2001): Monica Bacelli (Tamerlano), Tom Randle (Bajazet), Elizabeth Norberg-Schulz (Asteria), Graham Pushee (Andronico), Anna Bonitatibus (Irene), Antonio Abete (Leone)

- The English Concert ; Dir. Trevor Pinnock (181 min, also DVD)

- Opus arte OA 1006 (2008): Monica Bacelli (Tamerlano), Plácido Domingo (Bajazet), Ingela Bohlin (Asteria), Sara Mingardo (Andronico), Jennifer Holloway (Irene), Luigi De Donato (Leone)

- Orchestra of the Teatro Real Madrid; Dir. Paul McCreesh , director Graham Vick (DVD, 242 min incl. Extras)

- Naïve V 5373 (2014): Xavier Sabata (Tamerlano), John Mark Ainsley (Bajazet), Karina Gauvin (Asteria), Max Emmanuel Cencic (Andronico), Ruxandra Donose (Irene), Pavel Kudinov (Leone)

- Il Pomo d'Oro ; Dir. Riccardo Minasi (193 min)

literature

- Winton Dean , John Merrill Knapp : Handel's Operas 1704–1726. The Boydell Press, Woodbridge 2009, ISBN 978-1-84383-525-7 (English).

- Silke Leopold : Handel. The operas. Bärenreiter-Verlag , Kassel 2009, ISBN 978-3-7618-1991-3 .

- Arnold Jacobshagen (ed.), Panja Mücke: The Handel Handbook in 6 volumes. Handel's operas. Volume 2. Laaber-Verlag, Laaber 2009, ISBN 3-89007-686-6 .

- Bernd Baselt : Thematic-systematic directory. Stage works. In: Walter Eisen (Ed.): Handel Handbook: Volume 1. Deutscher Verlag für Musik , Leipzig 1978, ISBN 3-7618-0610-8 (Unchanged reprint, Kassel 2008, ISBN 978-3-7618-0610-4 ) .

- Christopher Hogwood : Georg Friedrich Handel. A biography (= Insel-Taschenbuch 2655). Translated from the English by Bettina Obrecht. Insel Verlag , Frankfurt am Main / Leipzig 2000, ISBN 3-458-34355-5 .

- Paul Henry Lang : Georg Friedrich Handel. His life, his style and his position in English intellectual and cultural life. Bärenreiter-Verlag, Basel 1979, ISBN 3-7618-0567-5 .

- Albert Scheibler: All 53 stage works by Georg Friedrich Handel, opera guide. Edition Cologne, Lohmar / Rheinland 1995, ISBN 3-928010-05-0 .

- John Merrill Knapp: Handel's Tamerlano: the Creation of an Opera. The Musical Quarterly, Vol. 56, 1970, pp. 405-430 (English) [1]

- John Eliot Gardiner & Jean-François Labie: Trade. Tamerlano. From the English by Ingrid Trautmann. Erato 2292-45408-2, 1987, pp. 27-31.

Web links

- Score by Tamerlano (Handel work edition, edited by Friedrich Chrysander , Leipzig 1876)

- Tamerlano : Sheet music and audio files in the International Music Score Library Project

- Libretto (PDF; 139 kB) by Tamerlano

- More information about Tamerlano

- First print (aria score) (John Cluer, London 1724) by Tamerlano

- Action and background of Tamerlano (English)

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b Christopher Hogwood: Georg Friedrich Handel. A biography (= Insel-Taschenbuch 2655). Translated from the English by Bettina Obrecht. Insel Verlag, Frankfurt am Main / Leipzig 2000, ISBN 978-3-458-34355-4 , p. 149 f.

- ↑ a b c Bernd Baselt: Thematic-systematic directory. Stage works. In: Walter Eisen (Ed.): Handel Handbook: Volume 1. Deutscher Verlag für Musik, Leipzig 1978, ISBN 3-7618-0610-8 (Unchanged reprint, Kassel 2008, ISBN 978-3-7618-0610-4 ) , P. 237 f.

- ↑ a b c d Winton Dean, John Merrill Knapp: Handel's Operas 1704–1726. The Boydell Press, Woodbridge 2009, ISBN 978-1-84383-525-7 , pp. 531 ff.

- ^ A b c d Jean-François Labie: Trade. Tamerlano. From the English by Ingrid Trautmann. Erato 2292-45408-2, 1987, p. 29 f.

- ^ John Eliot Gardiner: Trade. Tamerlano. From the English by Ingrid Trautmann. Erato 2292-45408-2, 1987, p. 27.

- ^ Editing management of the Halle Handel Edition: Documents on life and work. In: Walter Eisen (Hrsg.): Handel manual: Volume 4. Deutscher Verlag für Musik, Leipzig 1985, ISBN 978-3-7618-0717-0 , p. 130.

- ↑ Bertold Spuler: History of the Islamic countries. The Mongol period. Scientific Edition Society, Berlin 1948.

- ^ Burchard Brentjes: Chane, Sultans, Emirs. Koehler & Amelang, Leipzig 1974.

- ^ Charles Burney: A General History of Music: from the Earliest Ages to the Present Period. Vol. 4. London 1789, faithful reprint: Cambridge University Press 2010, ISBN 978-1-108-01642-1 , p. 297.

- ↑ Sir John Hawkins: A General History of the Science and Practice of Music. London 1776, new edition 1963, Vol. II, p. 878 ( online ).

- ^ Antoine Élisée Adolphe Cherbuliez: Georg Friedrich Handel. Otto Walter, Olten (Switzerland) 1949, p. 200.

- ↑ Walther Siegmund-Schultze: Trade: Tamerlano. CBS I3M 37893, 1983, p. 3.

- ^ Terence Best: Dramatic and scenic highlights in Handel's opera "Tamerlano". Handel yearbook, Deutscher Verlag für Musik, Leipzig, Halle 1991, p. 47.

- ^ Paul Henry Lang: George Frideric Handel. Norton, New York 1966, New Edition: Dover Publications, Mineola, NY (Paperback) 1996, ISBN 978-0-486-29227-4 , p. 182.

- ^ Paul Henry Lang: Georg Friedrich Handel. His life, his style and his position in English intellectual and cultural life. Bärenreiter-Verlag, Basel 1979, ISBN 3-7618-0567-5 , p. 162.

- ^ Paul Henry Lang: George Frideric Handel. Norton, New York 1966, New Edition: Dover Publications, Mineola, NY (Paperback) 1996, ISBN 978-0-486-29227-4 , p. 624.

- ^ Paul Henry Lang: Georg Friedrich Handel. His life, his style and his position in English intellectual and cultural life. Bärenreiter-Verlag, Basel 1979, ISBN 3-7618-0567-5 , p. 571.