Torsion gun

Torsion gun is a collective term for historical artillery weapons, which derive the energy required for the shot from the twisting of rope bundles that occurs during tensioning and the resulting elastic deformation of the surrounding frame. The ropes are usually made of animal tendons , but the use of oil-soaked woman's hair has also been handed down. The most famous weapons of this type are the Greek Palintona (Roman ballista or Scorpio) and the onager .

description

There are two types of construction: the one-armed (Onager) and the two-armed (Palintona / Balliste / Scorpio). In the one-armed design, the force for the ballistic throw is transmitted to the projectile by a throwing arm. Stones, metal balls, incendiary agents and the like can be used as projectiles. The trajectory of the projectiles is usually rather high (cf. steep fire gun ) and particularly suitable for indirect fire . The two-armed construction roughly corresponds to the structure of a crossbow , in that two arms transmit the force to a string and this in turn to the projectile. Bullets can also be used here, but spears and bolts are usually fired. The trajectory of the projectiles is rather flat (see flat fire gun ) and better suited for direct fire .

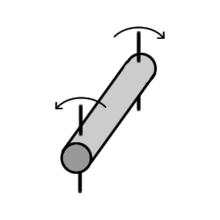

The acceleration is caused by a torque : two ropes or fiber bundles are strongly twisted by a stick pushed in between (torsion). This twist creates a strong preload (static energy). This mechanism is known as the Spanish Winch . If the stick is suddenly released and relieved, a strong torque (dynamic energy) is generated, which causes the stick to move quickly. This movement is transferred to the projectile and used as a throwing movement.

Compared to the guns based on lever throw ( Blide ), the construction and therefore also the projectile size is set a much lower limit.

The technical aspects of these weapons have so far been little researched in theory. The results are based primarily on experiments by private groups, since discoveries have only been made in recent years, for example on the Harzhorn event , which allow more precise conclusions to be drawn.

Torsion guns were used around 400 BC. Used on a larger scale by the Greeks. The Romans later adopted this technique and developed it further.

Roman Imperial Era

Principate

During the Principate's time, the army was responsible for the highly specialized manufacture of guns. It provided the skilled craftsmen and engineers and owned arms factories not only in Rome but also in the provinces. A tombstone from around 100 AD testifies to an engineer (architectus) who was commissioned to manufacture guns in the imperial arsenal (armamentarium imperatoris) in Rome. From two daily reports from the province of Aegyptus , which have been preserved on a papyrus from the second or third century AD, it is known that on these two days a hundred specialists (immune) in the legion workshops of the Legio II Traiana fortis in Alexandria were busy with it were, among other things, to produce clamping frames for torsion guns (capitula ballistaria) . Production in the army’s own workshops, which were subordinate to the camp commandant ( praefectus castrorum ) and managed by the optio fabricae , differs from the practice of late antiquity, when orders were given to private arms factories (fabricae) . The supreme command of the legionary factories in the provinces was not in the hands of the commander-in-chief of the legion ( legatus ) , but was under the control of the respective governor and his staff. There it was decided when production had to start. The archaeologist Dietwulf Baatz assumed that the decision to build it was made at such a high command level, as the work and material expenditure and the associated costs for such a special product were considerable.

Late antiquity

The entire arsenal of the Roman war machines remained in use during late antiquity. The late Roman torsion guns in particular are among the most complex mechanical machines of antiquity. The most important type was the ballista , which could fire bolt projectiles and incendiary arrows. These include both the standing guns and the variants on wheels (carroballista) . A handy variant of the one-man torsion gun, which was already in use during the middle imperial period, was the late antique torsion crossbow, which was - widespread - even used in small border forts such as the Romanian Gornea. After production had passed from the hands of the military to private companies during late antiquity, Roman weapons also ended up in hands that they were not supposed to receive. As a result, various emperors - such as Justinian I in AD 539 - issued decrees to limit production. As noted in the Notitia dignitatum , a Roman state handbook from the first half of the 5th century, there was an artillery officer in command (praefectus militum ballistariorum) who was subordinate to the military leader of the Mainz military district ( Dux Mogontiacensis ) . Other ballista units were subordinate to the respective army master ( magister militum ) of the dioceses . In the Diocese of Gaul, the artillery was commanded by the Commander in Chief of the Cavalry (magister equitum per Gallias) . In this context, this commander was apparently only subject to a legio pseudocomitatensis with a unit of ballistarii . The army master of the eastern diocese (magister militum per Orientem) was in command of the ballistarii seniores - a legio comitatensis - and a legio pseudocomitatensis of the ballistarii Theodosiaci . The army master of the Thracian diocese (magister militum per Thracias) was entrusted with two legiones comitatenses , consisting of the ballistarii Dafnenses and the ballistarii iuniores. The army master of the Diocese of Illyria (magister militum per Illyricum) could only send an artillery force, the ballistarii Theodosiani iuniores , into the field in an emergency . The Notitia dignitatum also mentions two fabricae ballistariae , both of which were in the diocese of Gaul, one in Augustodunum ( Autun ), the other in Triberorum ( Trier ).

Experimental example on torsion

To do this, take a knotted cord two hand widths long and place it tightly over the thumb and forefinger of the left hand, similar to the thread play . Now insert a match between the threads with the other hand and use it to twist the cord a few times. When you let go of the match, it spins around, just like the arm of a torsion weapon.

literature

- Dietwulf Baatz: Buildings and catapults of the Roman army . Mavors XI, Steiner, Stuttgart 1994, ISBN 3-515-06566-0

- Dietwulf Baatz: Catapult clamping bushes from Auerberg . In Günter Ulbert - The Auerberg I . Beck, Munich 1994, ISBN 3-406-37500-6 , pp. 173-189

- Dietwulf Baatz: Recent Finds of Ancient Artillery. In: Britannia , Vol. 9 (1978), pp. 1-17

- Dietwulf Baatz: The Hatra torsion gun. In Antike Welt , 9/4 (1978), pp. 50-7

- W. Gohlke: The guns of antiquity and the Middle Ages , in Volume 6 (1912-1914) of the magazine for historical weapons, publisher: Association for historical weapons, Dresden, 1915, pages 12 to 22. (online digitized)

- Nicolae Gudea , Dietwulf Baatz: Parts of late Roman ballista from Gornea and Orsova (Romania) . In Saalburg-Jahrbuch , Volume 31, 1974, pp. 50-72

- Erwin Schramm: The ancient artillery of the Saalburg . Reprint of the 1918 edition. Supplement to the Saalburg yearbook, Saalburg Museum, Bad Homburg vdH 1980, pp. 40–46

- Alexander Zimmermann: Two similarly dimensioned torsion guns with different construction principles - reconstructions based on original parts from Cremona (Italy) and Lyon (France) . In Journal of Roman Military Equipment Studies , 10 (1999) (= Roman Military Equipment 11), pp. 137-140

Web links

- Siege engines (heavy siege equipment) . Website of the Institute for Historical Regional Studies at the University of Mainz eV

- Fortress War Pages by Peter Rempis, subject librarian at the University of Tübingen

- roemercohorte.de Private pages of the Römercohorte Opladen with replicas and experiments on the torsion gun

Remarks

- ↑ Roman horror weapons in the weather test at spiegel.de

- ↑ Oliver Stoll : "Ordinatus Architectus" - Roman military architects and their significance for technology transfer. In Oliver Stoll - Roman Army and Society , Steiner, Stuttgart 2001, ISBN 3-515-07817-7 , pp. 300–368; here p. 306

- ↑ Dietwulf Baatz: Catapult clamping bushes from Auerberg. In Günter Ulbert : Der Auerberg I. Beck, Munich 1994, ISBN 3-406-37500-6 , pp. 173-189; here p. 185

- ↑ Nicolae Gudea, Dietwulf Baatz: Parts of late Roman ballists from Gornea and Orsova (Romania). In Saalburg-Jahrbuch , Volume 31, 1974, pp. 50-72; here p. 69

- ↑ Dietwulf Baatz: Catapults and mechanical hand weapons of the late Roman army . In Jürgen Oldenstein , Oliver Gupte (Hrsg.) - Spätrömische Militärausnung , Armatura, 1999, ISBN 0-9539848-1-8 , p. 14

- ↑ Alexander Demandt - The late antiquity. Roman history from Diocletian to Justinian 284-565 AD. Beck, Munich 2007, ISBN 978-3-406-55993-8 , p. 308

- ↑ Notitia dignitatum, Occ. 41, 23

- ↑ Notitia dignitatum, Occ. 7, 97

- ↑ Notitia dignitatum, Occ. 7, 8 = 43

- ↑ Notitia dignitatum, Occ. 7, 21 = 57

- ↑ Notitia dignitatum, Occ. 8, 14 = 46

- ↑ Notitia dignitatum, Occ. 8, 15 = 47

- ↑ Notitia dignitatum, Occ. 9, 47

- ↑ Notitia dignitatum, Occ. 9, 33