Harzhorn event

Coordinates: 51 ° 49 ′ 56.6 ″ N , 10 ° 6 ′ 17.9 ″ E

| "Harzhorn event" (sites on the Harzhorn) | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Archaeological excavations on the Harzhorn, 2012 |

||

| location | Lower Saxony , Germany | |

| Location | Harzhorn | |

|

|

||

| When | Roman Imperial Era | |

| Where | Wiershausen , District of Northeim / Lower Saxony | |

|

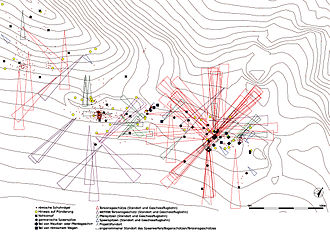

Location of the find area in detail |

||

The term Harzhorn event encompasses several related combat operations that took place between several thousand Roman legionaries and their auxiliaries as well as an unknown number of Teutons around the year 235/236 AD on the western edge of the Harz , on the Harzhorn , and a comparatively late example of the represent military presence of the Romans in Germania .

The archaeological sites are located near the Kalefeld district of Wiershausen on the northern edge of the Northeim district in Lower Saxony and initially extended over an area of 2.0 × 0.5 kilometers (as of April 2009). At the end of 2010, another extensive site was discovered around three kilometers away. Both sites are rated by the scientists commissioned with the investigations as a spectacular discovery of extraordinary scientific importance: It is, besides the Kalkriese region , the best preserved ancient battlefield in Europe. There is a unique opportunity to examine the archaeological remains of a Roman army in action.

So far around 1700 artefacts of the fighting have been found (as of summer 2013). In addition to the Hedemünden Roman camp , the Bentumersiel site , the Wilkenburg Roman marching camp and the Kalkriese discovery region, the sites around the Harzhorn are one of the largest sites of Roman militaria in northern Germany. This find is also significant due to its classification in the historical events at the beginning of the so-called imperial crisis of the 3rd century . Previously, in historical research, such extensive military operations by the Romans were not considered possible for this time and in this area. According to the current status, it is as good as certain that the battle belongs to the context of the German Wars of Emperor Maximinus Thrax in the years 235 and 236 AD.

discovery

There was a first archaeological reference to the battlefield on the Harzhorn as early as 1990, which was not recognized as such. A 45 cm long Roman lance was found during canal construction work in Kalefeld . It seems possible that the lance entered the village in the backfill gravel of a gravel pit on the Harzhorn.

According to a legend, there was once a castle on the Harzhorn, a terrain spur above the Nettetal , not far from the Kalefeld district of Wiershausen . The knights Oldit and Dudit are said to have lived here. When their castle was destroyed in the Thirty Years War , they founded the villages of Oldenrode and Düderode . While searching for this medieval castle, two amateur archaeologists from Kalefeld discovered the discovery area on the Harzhorn as illegal probes in 2000. They took several artifacts such as projectile points, Achsnägel, a shovel pickax and a Hipposandale they initially saw as medieval. In 2008 one of the amateur archaeologists presented the photos of the finds with the question of their origin in a relevant internet forum. He got the answer that at least one of the pieces found came from Roman times. This assignment prompted him in June 2008 to immediately inform the responsible district archaeologist Petra Lönne in Northeim .

The archaeological investigations that began in the late summer of 2008 indicated that an extensive military conflict had taken place in the Harzhorn area in the early 3rd century AD. The public announcement of the discovery with the presentation of the finds on December 15, 2008 caused a stir throughout Germany. It was by the then Minister of Lower Saxony for Science and Culture Lutz Stratmann and Michael Wickman as district administrator of the district Northeim made. In media reports, based on the press release by the Lower Saxony Ministry of Science and Culture, there was talk of an archaeological find of the century and the Roman Battle of Kalefeld .

location

Immediate find area

The find area is located about one kilometer northeast of Wiershausen on the approximately two kilometer long and wooded ridge of the Vogelberg (336 meters above sea level), which runs in an east-west direction. The narrower find area is the eastern area of the Vogelberg, which here bears the name Harzhorn and is shaped like a spur . The elevation runs as a natural barrier towards the Harz Mountains to the east . The eastern counterparts of the Harzhorn are the Rodenberg and the Hohe Rott (330 meters above sea level), in between there is a narrow, 600 meters wide pass at 190 meters above sea level . The mountains seal off the Kalefelder basin from the valley of the Nette to the north , so that it was previously only possible to pass in a north-south direction through the pass. Today the Federal Highway 7 runs here . Since the Rodenbergbach runs in the pass, it seems to have been a swampy valley low in earlier times. Medieval ravines avoided it and, like today's B 248 , ran on the slope of the Harzhorn. It used to be the route of a historical trade and military route through the Leinetal . Even today, the Harzhorn is a bottleneck for the main traffic line from Northern Germany via the Hessian valley to the Wetterau .

The find area is not in the area of the lower pass, but on the ridge of the Harzhorn, where the slopes drop steeply to the north and are only passable in a few places. According to the current working hypothesis (as of 2014), Germanic troops could have blocked the pass area for the Romans marching south. The Roman troops then bypassed the pass over the ridge in order, among other things, to break through the steep northern slope with a successful infantry attack , strong long-range weapon support ( torsion guns, arrows) and an equestrian attack.

Another find area

As early as 2009, prospecting began in the spacious area surrounding the site, and the historical network of trails was also taken into account. The airborne laser scanning process used delivered a three-dimensional model of the terrain, eliminating the disturbing vegetation through forest cover. The systematic search, especially with metal detectors, was extended to a radius of up to ten kilometers to the north towards Seesen and south towards Northeim . It turned out that there were hardly any meaningful finds in agricultural areas and that the conditions for preservation and discovery were very different in forest areas.

In November 2010, another discovery area ( presumed location ) was discovered around three kilometers southwest of the Harzhorn am Kahlberg . The artefacts found there include a Roman dolabra (see finds), part of a helmet from the high imperial era and two denarii , which can also be dated to the time spectrum of the coins already found on the Harzhorn. Two Pila found there were probably bent in battle. A small ax and the neck yoke of a draft animal were also found. Because of the wagon and draft animal equipment found here, one can conclude that the Roman entourage was fighting the Germanic tribes, in which close combat weapons such as lances were used.

Research team

After the first report of the find in 2008, the Harzhorn research project soon formed as a working group to search for and coordinate further action . The project is coordinated by the district archaeologist of the Northeim district, Petra Lönne, and the Lower Saxony state archaeologist Henning Haßmann . The research team also includes the district archaeologist Michael Geschwinde from the Lower Saxony State Office for Monument Preservation ( Braunschweig base ) as director, as well as the excavation technician Thorsten Schwarz and the prospection technician Michael Brangs from the State Office . The provincial Roman archaeologist Günther Moosbauer from the University of Osnabrück , the numismatist Frank Berger from the Historical Museum in Frankfurt , Felix Bittmann from the Lower Saxony Institute for Historical Coastal Research and the prehistorian Michael Meyer from the Institute for Prehistoric Archeology at the Free University of Berlin were also involved in providing scientific support . The Harzhorn research project was financially supported in 2009 and 2010 in particular by the “PRO Lower Saxony” research funding program of the Lower Saxony Ministry of Science and Culture.

Archaeological prospecting

Since the first finds in 2008, archaeological prospection in the closer and wider area of the Harzhorn has continued for years. Since the presence of a larger Roman army unit was to be assumed on the basis of the finds made so far, research was carried out into further battlefields, approach and departure routes and storage areas. A team from Northeim District Archeology and the Lower Saxony State Office for Monument Preservation was responsible for the prospecting. For this purpose, battlefield archeology was used, the most important tools of which for researching battlefields are metal detectors .

In 2009, during the prospecting measures , the remains of a Roman supply wagon were found on a steep slope , which could have fallen down during the battle. In addition to parts of wagons, iron hoof boots were found that suggest mules were used as draft animals. On the northern slope of the Harzhorn, larger concentrations of weapons were found, which indicate a very fierce battle. In a small area of the slope, around 40 catapult projectiles from torsion guns were stuck in the ground. The shooting directions could be reconstructed based on their orientations. Overall, most of the finds are weapons and weapon parts, including around 50 arrowheads, around 130 catapult projectiles, spearheads, armor and nails from legionnaires' sandals ( Caligae ). Other finds were Roman horseshoes , remains of chain mail , a bronze tinned sleeve hinge fibula , tent pegs and a belt set. 16 of the coins found were important for the chronological classification. These included the initial surprise of the researchers, the first one dating to the time of Augustus had expected nine Silberdenare from the time of the Severan emperors and two coins, the coins to the years from 228 n. Chr. Under Emperor Alexander Severus set let. In the wider area around the Harzhorn, only a few weapon parts have so far been located in the ground. This could be explained by weaker fighting, looting, overburdening by slope slides or by poorer conservation conditions in the soil structure there. Large areas of medieval Wölbacker corridors could also be used to disrupt found situations .

New prospecting measures took place in 2018 when the nearby BAB 7 was expanded . Shoe nails from Roman sandals from the 3rd century were found near Oldenrode.

Excavations

Archaeological excavations have so far only taken place in the immediate find area. The battlefield archeology strategies already used in the previous prospecting were intensified. The excavations are carried out under the direction of the prehistorian Michael Meyer by students from the Institute for Prehistoric Archeology at the Free University of Berlin, with excavation campaigns lasting several weeks between 2009 and 2013. The vastness of the site allows only exemplary excavation cuts. So far, they have taken place in seven excavation areas through 11 excavation cuts (status: 2010). The areas differ from the range of finds as well as from the terrain situation.

The focus of the almost four-week excavation in August 2012 was the eastern area of the ridge, on which a high concentration of shoe nails was found during previous prospections with metal detectors. During the excavation, three excavation cuts around 14 meters long and up to 4.5 meters wide were made, in which sandal nails, arrowheads, catapult bolts and a spearhead were found. The 2013 excavation campaign again concentrated on this area of the main ridge in an area with a high density of Roman metal parts, among which remains of a Roman chain mail were found.

Fund preservation conditions

The excavations to date have mainly taken place on the main ridge of the Harzhorn in the eastern area, where there is a high density of Roman objects. The area consists of forest, which belongs to the Gutswald of the Freiherr von Oldershausen family. In the slope areas, the rendzina soils provide ideal conservation conditions for the remains of historical war material thanks to an alkaline soil environment with limestone in the subsoil and a thin top layer of humus . In addition, because of their steepness and stony subsoil, these locations were not used for agricultural purposes, so that the finds could be preserved in situ undisturbed . In shallower areas with washed-off soil, the soil consists of soil types of decalcified brown earth , parabrown earth and loess , which apparently contributed to the regular find decomposition. In the flatter areas, however, there was also earlier agricultural use by Wölbackers , which resulted in the destruction of historical material.

Found objects

The find database so far comprises around 3,100 artifacts (as of summer 2013), of which, subject to further investigations, around 1,700 are relatively certain from the third century in question and of Roman origin. Only four found objects are verifiably of Germanic origin. Most of the finds were made during prospecting with metal detectors . The largest group of finds consists of approx. 1400 Roman shoe nails. The second largest group of finds, with 214 finds, includes remnants or projectiles of long-range weapons , such as catapult bolts, arrow, spear, lance and pila points. Most of them are catapult bolts with 131 specimens, many of which have tips deformed by the force of the impact. The average length of the floors is between 6 and 13 centimeters. So far 43 arrowheads have been found, including 24 three-winged points. Further finds are a Roman brooch made of bronze, fragments of an iron chain mail, iron belt trimmings, an iron sheath and a counter fitting . 16 artifacts are remains of Roman cars, including a bronze Jochaufsatz for the rope guidance, Achsnägel, Hippo sandals , as well as parts of a curb and a bridle .

The entire front area of a horse or mule skeleton was found in a clay-filled pit on the northeast slope of the Harzhorn. C14 investigations and a found lance tip suggest that the animal was hit in the course of the fighting and must have died as a result. When he fell into a tree pit, the skeletal remains that have now been examined have been preserved.

One of the extraordinary finds is a well-preserved Roman dolabra that weighs almost 2.5 kilograms and is almost 45 centimeters long, discovered at the end of 2010 . The LEG IIII SA signs were stamped on one iron side . The archaeologist Günther Moosbauer deciphered the inscription together with the ancient historian Rainer Wiegels . They assigned the tool to the Legio IIII Flavia Severiana Alexandriana (or Legio IIII Flavia Felix ) based on the characters . This unit, which in the 3rd century had its main camp in Singidunum , today's Belgrade , in what was then the Roman province of Moesia superior (Upper Moesia ), was considered to be particularly effective. The find is taken as further evidence of the participation of legionnaires in the battle. In principle, it is conceivable that the Dolabra was last in enemy hands, but this can be considered highly unlikely.

Another important find was made on August 12, 2013: A largely complete Lorica Hamata , a Roman chain mail , was discovered on the Harzhorn main ridge, on the edge of the main battle events previously prospected . The metal chain armor , corroded into several lumps of metal over time, was only three to ten centimeters below the surface of the earth. Part of the find has already been cleaned and prepared in the Lower Saxony State Office for Monument Preservation. The shirt represents another important find, because on the one hand it is almost completely preserved, on the other hand finds of personal equipment of Roman legionaries in the Germania magna are extremely rare. The only other specimen found in what is now Germany is the almost completely preserved Roman chain mail from the Thorsberger Moor in Schleswig-Holstein.

Although no excavation took place in 2014, several hundred metal finds were uncovered during the superficial search. The finds include weapon parts, coins, horse harness and numerous sandal nails. A total of over 2,700 metal artifacts have been found since 2008.

- Found objects

The tip of a Germanic lance found on the Harzhorn with spout and decorations in restored condition

Part of a Roman helmet of the Niederbieber type with a notch that may have been made in battle, left

Reconstruction of the fighting

As part of the prospecting measures from 2008 onwards, archaeologists found catapult tips of torsion guns in two places at the height of the Harzhorn and suspected another spot in the valley near today's federal road 248.Since then, several attempts at firing with replicated torsion guns have taken place at the former battlefield in order to determine the penetration power, shot distance and Reconstruct the firing direction. The guns were each designed to fire in the direction where the catapult tips were dug up. On November 23, 2012, scientists and students from the Universities of Osnabrück and Trier as well as the Helmut Schmidt University carried out firing tests with six partly different gun replicas. The field guns, which weigh up to 200 kilograms and whose historical models were built between 200 BC. Used until 400 AD, students from the universities and a group of students from the Ising grammar school built it. The tests in the presence of the scientific companion of the excavations Günther Moosbauer led to the assumption that the firing distance at the time on the Harzhorn could have been 150 meters. However, according to other experiments, the projectiles can also fly up to 300 meters.

Find evaluation and classification

Find evaluation and working hypothesis

Based on the archaeological finds on the Harzhorn, it is only certain that an attack with catapult projectiles by archers took place from north to south. The responsible scientists are now convinced that the artefacts found can be attributed to Roman legionaries and auxiliary troops . Initially, some researchers did not want to completely rule out that it could have been a conflict between Germanic tribes, armed with weapons from Roman production. From other finds, for example from the Thorsberger Moor in Schleswig-Holstein, we know that numerous intra-Germanic conflicts were fought in the 3rd century, with the warriors also using Roman weapons. In the opinion of the scientists, however, other finds on the Harzhorn, including the numerous catapult projectiles from ballistae (torsion guns), now clearly indicate that a strong Roman unit, consisting of infantry, archers, heavy cavalry and artillery, was involved in a violent battle; because so far nothing is known of the fact that Teutons ever used this specifically Roman war technique. The strength of the Romans is estimated to be at least two cohorts (1000 men) up to 9000 men. Other finds also clearly show the presence of Imperial Roman soldiers. Since they were carrying heavy torsion guns and traveling wagons, they could not have been just a raid party . From contemporary literary sources such as Herodian we know that in the early 3rd century the imperial troops often marched in enemy territory in several formations, so-called columns of a few thousand men each. It could have been such a march column in this case too.

The working hypothesis suggests that it is very likely that the Roman troops were marching from the north. The pass leading south on the Harzhorn was apparently blocked by enemies. However, the excavations carried out so far have not revealed any traces of a blockage caused by barriers or post holes in palisades . The legionaries had to fight their way over the ridge using massive weapons, instead of marching through the lowland, which was presumably marshy at the time. Initially, attempts could have been made to storm the Harzhorn hill. After the alleged failure of this first attack, the Romans probably switched to the use of long-range weapons. Conversely, it may also have been the case that the use of ballistae preceded a counterattack by the infantry as planned: According to the excavators, the high concentration of projectiles at mid-height of the slope indicates that a Germanic assault took place here, which resulted in violent Roman fire got. Herodian reports that the Roman army preferred long-range weapons at that time, in contrast to the Germanic peoples. The location of the finds speaks for a success of Roman unity, probably thanks to their superior military technology. The decision seems to have been made by a successful flank attack by the imperial cavalry. The fact that the Romans also left a relatively large amount of material on the battlefield suggests that they continued to feel threatened and moved quickly on despite their victory. Another conceivable event is an attack by the Teutons on the Roman train, which the combat troops then hurried to help.

The further discovery area discovered in 2010, about three kilometers from the Harzhorn, with signs of a simultaneous armed conflict, also suggests that a large-scale military operation by the Romans took place here, who presumably also marched in several pillars. The battle on the Harzhorn will not have had a very high military significance.

Chronological order

Because of the early discovery of a coin depicting the emperor Commodus (180–192), as well as because of the equipment, the scientists initially only suspected that the fight took place after 180 AD (Commodus came to power) and before the middle of the 3rd century must have taken place when the equipment of the Roman army changed significantly. As a hypothetical dating, the early 3rd century was generally considered, whereby the time of the Germanic campaigns of the Roman emperor Caracalla (211-217) came into question. New found coins from the time of the emperors Elagabal (218–222) and Severus Alexander (222–235) meanwhile allow a further time limit; they exclude the German war Caracallas as a context and now point with a very high degree of probability to the reign of the emperor Maximinus Thrax (235–238). The numismatist Frank Berger initially dated the battle a little more carefully to the period between 230 and 235 AD. The latest coins that can be clearly dated to date, silver denarii from the year 225, form a term post quem as the final coin . This determines the earliest possible time of the battle. Some spearheads found also had old, uncarred remains of wood in their shaft, which were dated to an age of around 1800 years (+/- 30 years) using the C14 method . Similarly, with the Enddatierung to 240 n. Chr., The analysis fell from excavated bone remains of equidae from.

The combination of the numismatic and archaeological findings with the results of the scientific investigations results in a time window from 228 to around 240 AD.Due to the various archaeological and numismatic evidence, it is now almost certain that the fighting on the Harzhorn is in the Fall 235 AD and belongs in the context of the great Germanic War of Maximinus Thrax, whereby the numismatist Reinhard Wolters has suggested a date to 236 AD, since in his opinion the Roman advance into the interior of Germania, contrary to Herodian's report , Only in the second year of Maximinus reign took place, while in 235 AD there were only battles near the border.

Sources for the Germanic campaign 235/236

Significant in this context is the news of the Late Antique Historia Augusta that Emperor Maximinus Thrax, immediately after taking power in 235 from Mogontiacum, advanced with his troops between 300 (trecenta) and 400 (quadringenta) miles deep into Germanic territory, which was in the Act would correspond to northern Lower Saxony. However, since it was not considered possible that such a military action had taken place during the “Imperial Crisis of the 3rd Century”, this indication of the manuscripts, following a suggestion by the French classical philologist Claude de Saumaise , was always closed in the modern editions of the text triginta and quadraginta (30 or 40 miles) "corrected" . Only since the discovery of the battlefield near Kalefeld has there been clear evidence that the information in the Historia Augusta is reliable on this point and that an advance into the interior of Germania actually took place around 235. In 233 the Teutons had devastated Roman territory; in 235, under the new Emperor Maximinus, the counter-attack from Rome, which had already been prepared by Severus Alexander, took place.

The fact that the Legio IIII Flavia Felix played a special role in this campaign is supported by the fact that Maximinus gave it the honorary name Legio IIII Flavia Maximiniana , i.e. was named after himself. This could have been an award for special bravery, probably during the Germanic campaign. The fact that the Legion took part in an expeditio Germaniae is also documented by the (undated) epitaph of Aurelius Vitalis, one of their soldiers, from Speyer. It is currently controversial whether Maximinus actually, as the literary tradition indicates, attacked the Germanic peoples immediately after he came to power or whether the actual campaign did not take place until 236 (see the section on chronological order ).

In any case, the Historia Augusta reported that Germanic associations were able to be defeated in a great “battle in the moor ” (proelium in palude) in which the emperor was personally involved. Maximinus was temporarily separated from his army and got into a swamp before his troops could liberate him. This led to a heavy battle, which, given the very damp terrain, was like a kind of sea battle . It has not yet been clarified whether this brief, literarily over-worded description can be related to the battlefield near Kalefeld. What is certain, however, is that the emperor celebrated his campaign as a great victory and informed the Roman Senate in a written report that he had defeated Germania.

The Greek historian Herodian , who, unlike the author of the Historia Augusta (for whom his work served as a source), was a contemporary of the events, reports:

“ Maximinus penetrated deep into Germanic territory, took a lot of booty and gave his troops all the cattle that they could get hold of. The Teutons, meanwhile, had cleared the plains and the treeless areas and withdrew into the forests and swamps, so that the fighting would take place where the dense trees would render the projectiles and arrows of their enemies ineffective, and where the deep moors the Romans would would threaten those who did not know the landscape […] . And so most of the battles took place in such areas, and it was here that the emperor himself took part very bravely in a battle: When the Teutons retreated into a large, damp depression and the Romans hesitated to follow them, Maximinus fell even in the lowlands, until the water was up to his horse's stomach; and so he struck at the enemies who surrounded him. Then the soldiers, ashamed of the fact that they had abandoned their emperor, who was fighting in their place, in the lurch, and attacked too. Large numbers of men fell on both sides, but while many Romans lost their lives, almost the entire barbaric army was destroyed and the emperor was the eminent man on the battlefield […] . Even more battles took place, in which Maximinus gained fame because of his personal involvement, since he always fought with his own hands and was the best warrior on the battlefield in every battle [...] . He threatened and was determined to defeat and subjugate all Germanic tribes up to the sea. "

When winter came, the emperor and his troops withdrew to the Rhine. In the following years he fought the Germanic tribes north of the Danube. The campaigns came to an abrupt end with Maximinus' assassination in the year of 238.

Historical classification

The events at Kalefeld took place over 200 years after the Augustan German Wars (up to 16 AD). These processes had marked the end of the Roman attempt to include the entire area up to the Elbe firmly in the empire. However, in the decades that followed, the Romans extended their border fortifications to Germanic territory in order to shorten the lines of defense, and thus also integrated the fertile Dekumatland into their direct territory. The indirect influence of the Roman Empire, however, extended far beyond the provincial borders, and research has long indicated the high level of political, cultural, and economic interaction between the Roman Empire and Germania magna . Treaties ( foedera ) were concluded with many Germanic princes , and some were even appointed too active by the emperors . This served the indirect politico-military control of Germania. Until the late 4th century, Roman campaigns into the right bank of the Rhine were repeatedly mentioned in the sources, which were mostly intended to deter or retaliate Germanic raids.

Roman writers - namely Cassius Dio , Herodian and the author (s) of the Historia Augusta - clearly report major campaigns east of the Rhine and north of the Danube in the 3rd century, especially for the reigns of Emperors Caracalla (in the year 213) and Maximinus Thrax ( in 235). Until 2008, however, there was no archaeological evidence in Germania magna for these literary traditions . Above all, however, ancient historical research was in the dark about the actual radius of these military operations and generally only accepted very limited military operations in relative proximity to the Limes . The few references to the contrary in literary sources were considered an implausible exaggeration.

This is where the main historical significance of the site near Kalefeld for knowledge of Roman history on today's German soil lies : The interpretation based on the finds indicates that the interior of Germania was actually the target of Roman military operations in the 3rd century. Until 2008, very few researchers would have thought it possible that Roman legionaries not only operated in the Limes foreland during the beginning of the imperial crisis of the 3rd century , but also advanced into what is now northern Germany. According to literary sources, the Roman campaigns primarily served to secure the Roman imperial frontiers on the Rhine and Danube as well as (in the context of retaliatory campaigns) to protect the Dekumatland, which was evacuated around 260 ( Limesfall ). One must now consider, however, that the direct Roman influence, possibly underpinned militarily, possibly extended much further into the interior of Germania 225 years after the Varus Battle than was assumed for a long time.

presentation

Permanent installation on site

Concept and location

After extensive prospecting and recoveries, the Harzhorn area was opened to the public in May 2010. Since then, there have been regular tours of the site for visitors, which are carried out by trained Harzhorn guides . In 2015, 25 Harzhorn guides took around 4,000 visitors around the site, while around 6,500 people visited the information building. In 2017, around 5600 visitors, including around 1000 school children, were shown around the area.

The finds have been exhibited in the Braunschweigisches Landesmuseum so far (2017) due to ongoing restorations and investigations .

The district of Northeim and the municipalities of Kalefeld and Bad Gandersheim use the site as an archaeological open-air museum under the slogan “Roman battle on the Harzhorn” . A logo was developed for this purpose and secured as a trademark . The Technical University of Aachen developed the tourism concept until 2012. There is a three-stage plan for the tourist development. Under the leadership of the district of Northeim, Rome's forgotten campaign was until the Lower Saxony State Exhibition . The Battle of the Harzhorn 2013/2014 in Braunschweig built a tourist infrastructure with paths, information points, signs and an information building on the site. The second stage includes the regional integration with the help of cycle paths as well as the construction of a lookout tower and a connection to the Roman camp Hedemünden through a "Roman motorway". In the third stage, a visitor center for five million euros could be built. So far (2018) only the first stage has been implemented.

In 2013 it became known that a 50 meter wide green bridge was being built over the A7 directly in the pass area of the Harzhorn in order to connect the two largest forest areas in Lower Saxony, Harz and Solling , for wildlife. This meant that the location of the information building for visitors to the Harzhorn had to be relocated by 250 meters. The information building was built on the edge of the Vogelberg forest above the B248 and was partially opened in November 2013. In June 2014, it was officially opened on Architecture Day . The President of the Lower Saxony State Office for Monument Preservation, Stefan Winghart, described the Harzhorn project as a "model case for modern battlefield archeology ", which is why his authority played a key role in it.

Infrastructure

The first expansion stage included the construction of an access road, a visitor parking lot, an information building and the erection of information steles along a 650-meter-long path. There are QR codes on the steles for use with a mobile app that provides interested visitors with detailed information on the respective location. This includes a code that refers to the Wikipedia article on the Harzhorn event.

The location of the futuristic-looking information building has been chosen so that it can be seen from the BAB 7 motorway below . A balcony on the building offers a view of the valley between the Harzhorn and Rodenberg, through which the Romans presumably approached. The building design, the shape of which often takes up points and edges as a reminiscence of the pointed and angular weapon technology of that time, comes from an architectural office in Uslar . The cladding of the information building and the steles along the path are made of gold-colored metal and untreated wood. These materials are intended to symbolize the peoples involved in the conflict on the Harzhorn. The metal stands for the Romans with their mostly metallic equipment, whereas the Teutons are characterized by raw wood.

In November 2013, the tourist infrastructure was largely completed. The costs up to then amounted to around 800,000 euros, of which around 600,000 euros went to the information building. When the information building opened in June 2014, costs of 905,000 euros were mentioned. The costs incurred were borne by the Northeim district and its cultural and monument foundation, the Lower Saxony Ministry of Science and Culture, the Lower Saxony Sparkasse Foundation, the Northeim district savings bank, the Office for Rural Development and the Bingo environmental foundation! .

Ten years after the discovery of the site, plans to expand the information path into a circular route became known in 2018. The reason was the increasing number of visitors. During the work that began in 2019, the circular route was expanded by two information stations and a weatherproof shelter for visitors was created at the information building, which is not open all the time. The work was funded in the amount of around 200,000 euros, largely by the Federal Government Commissioner for Culture and the Media and as part of the LEADER program. The work was completed in 2020.

Lower Saxony state exhibition

The Lower Saxony State Exhibition Rome's forgotten campaign dealt with the Harzhorn event . The Battle of the Harzhorn , which ran from September 1, 2013 to March 2, 2014. It was shown in the Braunschweigisches Landesmuseum on 1000 m² of exhibition space. The show presented the fighting on the Harzhorn, as well as the life of Roman legionaries and Teutons in the 3rd century AD. Approx. 400 exhibits from the battlefield and 400 exhibits from partly private lenders were shown, including a bust of Maximinus Thrax from the Capitoline Hill Museums in Rome. The state of Lower Saxony provided 650,000 euros for the state exhibition, including 100,000 euros for the infrastructure on the Harzhorn, of the total of 1.8 million euros in exhibition costs.

At the same time as the state exhibition, just a few meters from the state museum, the accompanying exhibition Caesars, Heroes and Saints - The Roman Soldier in Modern Representations took place in the bower of Dankwarderode Castle . It presented idealized representations of Roman soldiers in the form of everyday objects and works of art. They come from the epochs of the Renaissance and the Baroque , when "the Roman" was a symbol of strength and willingness to fight.

The national exhibition saw 68,264 visitors. It ranks 3rd in terms of visitor numbers for exhibitions in Braunschweig over the past 20 years. First place was the Troy exhibition, which attracted around 330,000 visitors in 2001, followed by Henry the Lion and his time in second place . Rule and representation of the Guelphs 1125–1235 , who in 1995 saw around 100,000 visitors.

Portal to history

The topic was presented comprehensively in 2016 in the portal on history at the Brunshausen monastery site, i.e. in close proximity to the authentic site. The exhibition included not only the presentation of processed finds from antiquity, but also a representation of the connection between the locations and processes of the Harzhorn event.

Exhibition in Berlin

From September 21, 2018 to January 6, 2019, some finds from the Harzhorn were shown in the exhibition Moving Times. Archeology in Germany shown in the Martin-Gropius-Bau in Berlin . The exhibition was part of the European Cultural Heritage Year 2018.

literature

- Frank Berger , Felix Bittmann, Michael Geschwinde, Petra Lönne , Michael Meyer , Günther Moosbauer : The Roman-Germanic conflict on the Harzhorn (district Northeim, Lower Saxony). In: Germania . 88, 2010, pp. 313-402. ( Online )

- Ulrike Biehounek: The Romans' revenge . In: Image of Science . Issue 6, 2010, pp. 84-89.

- Michael Geschwinde : Rome's forgotten campaign: the Harzhorn event. In: Babette Ludowici (ed.): Saxones. Theiss, Darmstadt 2019, pp. 76–77.

- Michael Geschwinde u. a .: Rome's forgotten campaign . In: Museum and Park Kalkriese (ed.): 2000 years of the Varus Battle. Conflict . Theiss, Stuttgart 2009, pp. 228-232.

- Michael Geschwinde, Petra Lönne: The trail of the sandal nails. In: Archeology in Germany . 2/2009, ( denkmalpflege.niedersachsen.de ), ( denkmalpflege.niedersachsen.de PDF; 500 kB)

- Gustav Adolf Lehmann : Imperium and Barbaricum. New findings and insights into the Roman-Germanic disputes in northwestern Germany - from the Augustan occupation phase to the Germanic procession of Maximinus Thrax (235 AD) . Publishing house of the Austrian Academy of Sciences, Vienna 2011, ISBN 978-3-7001-7093-8 , p. 102 ff.

- Ralf-Peter Märtin : The revenge of the Romans . In: National Geographic . June 2010, pp. 66-93.

- Günther Moosbauer : The forgotten Roman battle. The sensational find on the Harzhorn. CH Beck, Munich 2018, ISBN 978-3406724893 .

- Heike Pöppelmann, Korana Deppmeyer, Wolf-Dieter Steinmetz (eds.): Rome's forgotten campaign. The battle of the Harzhorn. Catalog for the Lower Saxony State Exhibition. ( Publications of the Braunschweigisches Landesmuseum , 115). Theiss, Stuttgart 2013, ISBN 978-3-927939-85-1 ; ISBN 978-3-8062-2822-9 (comprehensive presentation of the sources and research on the Harzhorn event).

- Rainer Wiegels , Günther Moosbauer, Michael Meyer, Petra Lönne, Michael Geschwinde with the assistance of Michael Brangs, Thorsten Schwarz: A Roman Dolabra with an inscription from the area around the battlefield on the Harzhorn (district of Northeim) in Lower Saxony. In: Archaeological correspondence sheet. 41, 2011, pp. 561-570.

Film documentaries

- Riddle Roman battle on the Harzhorn , television documentary by NDR television from 2008

- The Battle of the Harzhorn - Rome's last campaign to Germania (Documentation, 2010)

- Roms Rache , documentary in the series ZDF-History (broadcast November 6, 2011, 201tube.net )

- Terra X - Germany's super excavations , ZDF television broadcast, 2012

Web links

- Roman battle on the Harzhorn: The discovery of a Roman-Germanic battlefield from the 3rd century AD (information page), on the website of the Harzhorn Working Group

- Petra Wundenberg: Archaeological find of the century. Lower Saxony Ministry for Science and Culture (press release), December 15, 2008

- Battlefield on the Harzhorn , in the RegioWiki of the Hessian / Lower Saxony General

- Ralf-Peter Märtin : Roman battlefield discovered: the Teutons drive into the swamp. In: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung . December 17, 2008

- Archeology: Advance after the Varus Battle. In: Focus Online . December 16, 2008

- Nicolaus Schröder: Searching for traces on the Harzhorn - the momentous story of a find. (Report), Deutschlandradio , August 27, 2010

- Reimar Paul: Battlefield: Two-three-zero, near Kalefeld with a roar. In: the daily newspaper . April 17, 2009

- Searching for traces on the Roman battlefield on the Harzhorn. (Video of the 2012 excavation, 59 seconds), Hessische / Niedersächsische Allgemeine Online

- Fight like the Romans on the Harzhorn. ( Memento from November 27, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) Norddeutscher Rundfunk , November 24, 2012

- Aerial view of the Vogelberg ridge with Harzhorn from the south , Die Welt

- Report and photos of the inauguration of the information building and the themed trail on the Harzhorn with a seven-minute video of the Northeim district

- Rome's forgotten campaign - the discovery of a Roman battlefield from the 3rd century on the Harzhorn near Kalefeld, District Northeim ( Memento from February 23, 2010 in the Internet Archive ) (Harzhorn research project), discontinued website of the Lower Saxony State Office for Monument Preservation at Internet Archive

- “We have become part of Roman history” , Braunschweiger Zeitung of March 23, 2014.

- In the footsteps of the Roman Battle of the Harzhorn as a summary report by NDR from January 7, 2015

Remarks

- ↑ This is also not an open field battle, but, in military terms, a "battle". In order to conduct a discussion that is as objective as possible and not already predetermined by terminology, it makes sense to use the neutral term "Harzhorn event". Michael Geschwinde, Petra Lönne, Michael Meyer: Frozen time. The Harzhorn event - archeology of a Roman-Germanic confrontation 235 AD. In: Matthias Wemhoffs , Michael Rind (Ed.): Moving times: Archeology in Germany. Michael Imhof Verlag, Petersberg 2018, ISBN 978-3-7319-0723-7 , p. 283.

- ↑ a b c Michael Geschwinde, Petra Lönne, Günther Moosbauer with the collaboration of Michael Brangs and Thorsten Schwarz: The secret of Dolabra. In: Reports on the preservation of monuments in Lower Saxony. 4/2011, pp. 248-249.

- ^ The battlefield at the Harzhorn: New archaeological investigations 2009 and 2010. In: Reports on the preservation of monuments in Lower Saxony. 1/2011, p. 25.

- ↑ Michael Geschwinde: A Roman ceremonial lance from Kalefeld, Ldkr. Northeim In: Nachrichten aus Niedersachsens Urgeschichte , vol. 84, Stuttgart 2015, p. 107ff.

- ↑ Legends from Olderode-Düderode on the website of the village of Düderode, accessed on December 7, 2018.

-

↑ Lower Saxony Monument Protection Act of May 30, 1978 § 12 "Excavations"

(1) Anyone who digs for cultural monuments, retrieves cultural monuments from a body of water or wants to search for cultural monuments with technical aids requires a permit from the monument protection authority. Research carried out under the responsibility of a state monument authority is excluded.

(2) Approval shall be refused if the measure violates this Act or would impair research projects in the state. Approval can be granted subject to conditions and with requirements. In particular, provisions can be made on the search, planning and execution of the excavation, the treatment and securing of the excavation finds, the documentation of the excavation findings, the reporting and the final preparation of the excavation site. A specific expert may also be required to direct the work. - ^ First Roman finds ten years ago. In: Hessische / Niedersächsische Allgemeine . January 6, 2010. See also: Michael Geschwinde, Petra Lönne: The discovery of a battlefield that actually couldn't exist. In: Heike Pöppelmann, Korana Deppmeyer, Wolf-Dieter Steinmetz (eds.): Rome's forgotten campaign. The battle of the Harzhorn. Konrad Theiss, Darmstadt 2013, pp. 58–64, here pp. 60 f.

- ↑ Roman battlefield discovered on the edge of the Harz. Archeology Online, December 15, 2008.

- ↑ Petra Wundenberg: Archaeological Find of the Century , Lower Saxony Ministry for Science and Culture (press release), December 15, 2008.

- ↑ Romans also fought on the Kahlberg - pioneer ax gives a lot of information. In: Hessische / Niedersächsische Allgemeine . January 11, 2012.

- ↑ Berger, Bittmann, Geschwinde, Lönne, Meyer, Moosbauer, p. 313 (preliminary remark)

- ↑ Michael Meyer: Roman battlefield on the Harzhorn near Northeim ( Memento from October 4, 2013 in the Internet Archive ), Freie Universität Berlin, 2009.

- ↑ The Roman Battle of the Harzhorn , GeschiMag, the online history magazine, April 20, 2009.

- ↑ Berger, Bittmann, Geschwinde, Lönne, Meyer, Moosbauer, p. 313 (preliminary remark)

- ↑ Ulrike Biehounek: The Revenge of the Romans , Bild der Wissenschaft Online 6/2010.

- ↑ Battle of the Harzhorn: chain mail of a Roman soldier found at archäologie-online.de on July 3, 2015

- ↑ Max Brasch: Archaeologists uncover 7,200-year-old settlement remains in the Göttinger Tageblatt of March 5, 2018

- ^ Eva Werler: New excavations on the Harzhorn ( memento from August 9, 2012 in the Internet Archive ), Norddeutscher Rundfunk Online, August 9, 2011.

- ↑ Continuation of the excavations on the Roman-Germanic battlefield Harzhorn at the Association of State Archaeologists

- ↑ Start of this year's excavation campaign: Roman-Germanic battlefield Harzhorn , Germany today, August 1, 2012.

- ↑ Battlefield on the Harzhorn: 20 archeology students during summer excavation. In: Hessische / Niedersächsische Allgemeine . 22nd August 2012.

- ↑ a b Students dig again on the ancient battlefield on the Harzhorn in hna.de from July 19, 2013.

- ↑ What happened at the Battle of the Harzhorn? ( Memento from July 27, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) on ndr.de from July 21, 2013.

- ↑ Another spectacular find on the Harzhorn. on hna.de from August 15, 2013.

- ^ Frank Berger, Felix Bittmann, Michael Geschwinde, Petra Lönne, Michael Meyer, Günther Moosbauer: The Roman-Germanic conflict on the Harzhorn (district Northeim, Lower Saxony). In: Germania. 88, 2010, p. 334 (the found material).

- ↑ Berger, Bittmann, Geschwinde, Lönne, Meyer, Moosbauer, p. 334 (The overall distribution of the finds).

- ↑ Berger, Bittmann, Geschwinde, Lönne, Meyer, Moosbauer, p. 335 (weapons).

- ↑ Berger, Bittmann, Geschwinde, Lönne, Meyer, Moosbauer, p. 343 (harness and wagon).

- ↑ Berger, Bittmann, Geschwinde, Lönne, Meyer, Moosbauer, pp. 356–364 (The archaeological excavations).

- ↑ Rome's fourth legion waged war in Germania , Die Welt , January 8, 2012.

- ↑ Martin Sommer: Rome's Forgotten Battle , Kreiszeitung Online, January 12, 2012.

- ↑ Dankwart Guratzsch: Sensational Find: History of Greater Germany before the New Interpretation , Die Welt , January 11, 2012.

- ↑ Dietmar Vonend: The secret of Dolabra leads to the year 235. In: Reports on the preservation of monuments in Lower Saxony 1/2012; Inscription on battle ax: Roman Legion from Serbia on the Harzhorn , Göttinger Tageblatt , January 11, 2012; Florian Arnold: Like the ax in the Germanenwalde , Braunschweiger Zeitung Online, January 11, 2012.

- ↑ Thomas Brock: Roman weapon find: Die Axt vom Harzhorn , Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung , January 14, 2012.

- ↑ Harzhorn: Archaeologists find chain mail. in hna.de from August 15, 2013.

- ↑ Chain mail of a Roman soldier found at Scinexx.de on August 16, 2013

- ↑ Archaeologists discover chain mail from the Battle of the Harzhorn. (with 6 photos), In: Spiegel Online . August 15, 2013; True story: The legionnaire in chain mail. ( Memento from October 3, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) at ndr.de from August 15, 2013.

- ↑ The rusty remains of the battle. In: Der Tagesspiegel . dated August 15, 2013; Sensational find - chain mail from the 3rd century at Deutschland Today on August 16, 2013

- ↑ Deutschlandfunk - broadcast research news. on August 16, accessed August 18, 2013.

- ↑ Archaeologists from the Free University of Berlin excavate largely preserved chain mail of a Roman soldier. Report from the Free University of Berlin from August 15, 2013; Battle of the Harzhorn: chain mail of a Roman soldier found. In: Archeology.online. 18th August 2013.

- ↑ Hundreds of new finds on the Roman battlefield at Göttinger Tageblatt on February 18, 2015

- ↑ Battle of the Harzhorn: Teutons in the Crossfire (with video film), Hessische / Niedersächsische Allgemeine Online, November 23, 2012.

- ↑ Reconstructed: Roman artillery tested on an ancient battlefield , Die Welt , November 23, 2012.

- ↑ Antique military equipment tested: Roman artillery fires at Harzhorn , Hannoversche Allgemeine Zeitung, November 23, 2012.

- ↑ Roman field guns on the Harzhorn , press release from the University of Osnabrück, November 23, 2012, on archaeologie-online.de.

- ↑ The ancient historian Ralf Urban from the University of Erlangen-Nürnberg initially expressed cautious doubts : "The Romans did not throw away any weapons": Erlangen ancient historian has doubts about the sensational find (interview), Nürnberger Zeitung , December 16, 2008; Sensational find: researchers discover remains of Roman weapons , Spiegel Online , December 11, 2008.

- ^ A b Frank Berger : The Roman coins on the Harzhorn. In: Heike Pöppelmann, Korana Deppmeyer, Wolf-Dieter Steinmetz (eds.): Rome's forgotten campaign. The battle of the Harzhorn. Konrad Theiss, Darmstadt 2013, pp. 285–293.

- ^ The battlefield at the Harzhorn: New archaeological investigations 2009 and 2010. In: Reports on the preservation of monuments in Lower Saxony 1/2011.

- ↑ Reinhard Wolters: Recovered History. The campaign of Maximinus Trax into the interior of Germania 235/236 AD in the numismatic tradition . In: Heike Pöppelmann, Korana Deppmeyer, Wolf-Dieter Steinmetz (eds.): Rome's forgotten campaign. The Battle of the Harzhorn , Darmstadt 2013, p. 116 ff.

- ↑ Historia Augusta, Vita Maximini duo 12.1 .

- ↑ For general information on the campaign (taking into account the battle), see Gustav Adolf Lehmann : Imperium und Barbaricum. New findings and insights into the Roman-Germanic disputes in northwestern Germany - from the Augustan occupation phase to the Germanic procession of Maximinus Thrax (235 AD) . Vienna 2011, pp. 102–112.

- ↑ See also Klaus-Peter Johne: Die Römer an der Elbe on the passage in question . Berlin 2006, pp. 262–263, which, however, still assumes a copying error and a modest scope of the campaign.

- ^ AE 1952, 186 .

- ↑ CIL 13, 6104 .

- ↑ Historia Augusta , Vita Maximini duo 12.5.

- ↑ Herodian 7: 2, 5-9. For this passage see Martin Hose : Erased history. The campaign of Maximinus Thrax into the interior of Germania 235/236 AD in historical tradition. In: Heike Pöppelmann, Korana Deppmeyer, Wolf-Dieter Steinmetz (eds.): Rome's forgotten campaign. The battle of the Harzhorn. Konrad Theiss, Darmstadt 2013, pp. 111–115, especially pp. 113–115.

- ↑ In addition Henning Börm : The rule of the emperor Maximinus Thrax and the six-imperial year 238. In: Gymnasium . Volume 115, 2008, pp. 69-86 ( online ).

- ↑ New finds near Dögerode increase interest. In: Hessische / Niedersächsische Allgemeine . January 12, 2012.

- ↑ With Harzhorn guides on the battlefield ( memento from February 22, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) at ndr.de from February 21, 2015

- ↑ 25 percent more tours on the Harzhorn than in 2015 in Göttinger Tageblatt on February 9, 2016

- ↑ Record number of visitors on the battlefield in Göttinger Tageblatt on December 20, 2017

- ↑ The adventure center on the Roman-Germanic battlefield should come by 2015: Two steps for the Harzhorn. In: Hessische / Niedersächsische Allgemeine . April 20, 2012.

- ↑ The show ground at the Roman battlefield should be ready in 2013: District Northeim wants to develop the Harzhorn itself. In: Hessische / Niedersächsische Allgemeine . June 29, 2012.

- ↑ By 2013 the first paths, signs and information box for Roman terrain. In: Hessische / Niedersächsische Allgemeine . May 10, 2012 ( hna.de ).

- ↑ Wildautobahn crosses the A7 on the Harzhorn. In: Hessische / Niedersächsische Allgemeine . November 21, 2012 ( hna.de ).

- ↑ Harzhorn: Information center must give way to bridge ( memento from October 3, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) at ndr.de from June 7, 2013.

- ↑ Information building at the Römerschlachtfeld Harzhorn inaugurated at hna.de on June 29, 2014

- ↑ District Monument Foundation supports Harzhorn. In: Hessische / Niedersächsische Allgemeine . December 20, 2012 ( hna.de ).

- ↑ Information architecture officially opened at Deutschland Today on November 13, 2013.

- ↑ App leads across the battlefield In: Weser Kurier. November 13, 2013 ( weser-kurier.de ).

- ↑ Futuristic about the historic Harzhorn at ndr.de from November 12, 2013 ( Memento from November 14, 2013 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Matthias Heinzel: Harzhorn: information building opened In: Göttinger Tageblatt. November 12, 2013 ( goettinger-tageblatt.de ).

- ↑ Window into the past opened in Observer from July 3, 2014.

- ↑ Topping-out ceremony for the information building on the Harzhorn. Showcase into the past at: Deutschland today from September 12, 2013.

- ↑ Matthias Heinzel: Harzhorn presentation will be expanded in Göttinger Tageblatt on April 20, 2018

- ↑ Circular route and refuge: This is how it continues on the Harzhorn at Northeim-jetzt.de from December 18, 2019

- ↑ Harzhorn: circular route with new adventure stations in the Göttinger Tageblatt from July 22, 2020

- ↑ Extension of the exhibition until March 2, 2014

- ↑ The Romans come In: Waldeckische Landeszeitung. July 6, 2013.

- ↑ A forgotten campaign is taking shape ( memento from August 7, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) at ndr.de from July 30, 2013.

- ↑ Exhibition: The Battle of the Harzhorn Comes Back to Life. In: Hessische / Niedersächsische Allgemeine . October 1, 2012.

- ↑ Press release of the CDU parliamentary group in the Lower Saxony state parliament ( memento of December 30, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) of November 22, 2011.

- ↑ State promotes Harzhorn , Germany today, November 22, 2011; "Rome's forgotten campaign": State exhibition 2013 shows the Roman army in action , Hannoversche Allgemeine Zeitung , December 30, 2012.

- ↑ Accompanying exhibition Caesars, Heroes and Saints - The Roman Soldier in Modern Representations

- ^ Farewell to the Harzhorn , Braunschweiger Zeitung of February 27, 2014.

- ↑ exhibition

- ↑ film

- ↑ Michael Geschwinde, Petra Lönne, Michael Meyer: Frozen time. The Harzhorn event - archeology of a Roman-Germanic confrontation 235 AD. In: Matthias Wemhoffs , Michael Rind (Ed.): Moving times: Archeology in Germany. Michael Imhof Verlag 2018, ISBN 978-3-7319-0723-7 , pp. 283-293.

- ↑ 45 min Römerschlacht riddle at ndr.de from October 29, 2016.

- ↑ Florian Dedio, Georg Schiemann: The Battle of the Harzhorn - Rome's last campaign to Germania , Cinefacts , 2010.