Properdin deficiency: Difference between revisions

TEH-XM2119 (talk | contribs) Added Diagnosis section |

I added a management and epidemiology section. |

||

| Line 31: | Line 31: | ||

== Diagnosis == |

== Diagnosis == |

||

As mentioned before, there are no external indications of properdin deficiency, and as such, properdin deficiency can only be reliably detected by lab tests.<ref name=":0" /> In particular, the use of [[ELISA]] proves to be one of the most effective methods of detecting properdin deficiency, as the average healthy male is expected to show properdin antigen levels of around 128.0 ELISA units/ml, and obligate carrier females (recall that properdin deficiency is an X-linked disease) tend to show an average of 45.6 units/ml.<ref name=":0" /> An individual with properdin deficiency should, by definition, show very little to no properdin antigen levels at all, as they do not possess the requisite gene to produce the protein. |

As mentioned before, there are no external indications of properdin deficiency, and as such, properdin deficiency can only be reliably detected by lab tests.<ref name=":0" /> In particular, the use of [[ELISA]] proves to be one of the most effective methods of detecting properdin deficiency, as the average healthy male is expected to show properdin antigen levels of around 128.0 ELISA units/ml, and obligate carrier females (recall that properdin deficiency is an X-linked disease) tend to show an average of 45.6 units/ml.<ref name=":0" /> An individual with properdin deficiency should, by definition, show very little to no properdin antigen levels at all, as they do not possess the requisite gene to produce the protein. |

||

== Management == |

|||

Pertaining to complement deficiencies, there is no cure and the treatments for complement deficiencies vary widely. The best course of action for management is usually for a patient to treat the complement deficiency as an immune deficiency and get immunized against the microbe associated with their deficiency (or best candidate).<ref>{{Cite web |title=Complement Deficiencies {{!}} Immune Deficiency Foundation |url=https://primaryimmune.org/about-primary-immunodeficiencies/specific-disease-types/complement-deficiencies |access-date=2022-03-24 |website=primaryimmune.org}}</ref> As mentioned earlier, individuals with properdin deficiency are increasingly susceptible to Neisseria bacterium. Recent studies have indicated that individuals with properdin deficiency respond well when they are immunized with tetravalent polysaccharide meningococcal vaccine, which generates anti capsular antibodies and bactericidal anti-meningococcal activity against [[Serotype|serotypes]] covered by the given vaccine.<ref name=":1">{{Cite journal |last=Linton |first=S. M. |last2=Morgan |first2=B. P. |date=1999-11 |title=Properdin deficiency and meningococcal disease--identifying those most at risk |url=https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10540177 |journal=Clinical and Experimental Immunology |volume=118 |issue=2 |pages=189–191 |doi=10.1046/j.1365-2249.1999.01057.x |issn=0009-9104 |pmc=1905414 |pmid=10540177}}</ref> The vaccine has been reported to lower the chances of reinfection by meningococci in individuals who have undergone the treatment, however the vaccine does not protect against group B meningococci and chemotherapy is recommended if full protection from all meningococci variants is desired.<ref name=":1" /> |

|||

== Epidemiology == |

|||

Complement deficiencies are rare and currently not well characterized, so there has been difficulty detecting them. Currently, complement deficiencies only comprise approximately 2% of all [[primary immunodeficiency disorders]]. While the frequency of properdin deficiency has not been assessed worldwide, the risk of meningococcal infection in an individual with properdin deficiency has been calculated to be around 50%.<ref>{{Cite book |last=editor. |first=Leung, Donald Y. M., 1949- |url=http://worldcat.org/oclc/1202992443 |title=Pediatric allergy : principles and practice |isbn=978-0-323-67462-1 |oclc=1202992443}}</ref> |

|||

==References== |

==References== |

||

Revision as of 12:48, 24 March 2022

Introduction

| Properdin deficiency | |

|---|---|

| |

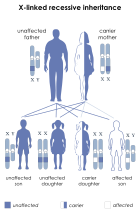

| This condition is inherited in an x-linked recessive manner |

Properdin deficiency is a rare X-linked disease in which properdin, an important complement factor responsible for the stabilization of the alternative C3 convertase, is deficient.[1] One of the first studied cases of properdin deficiency was in 1980 by Davis and Forrestal.[2] These families had members with only partial deficiencies which resulted in a lowered consumption of the C3 protein.[2] Properdin deficiency was studied again shortly after in 1982 by Sjoholm in which all of the subjects were deceased shortly after the study because of their disease.[2] The largest study of properdin deficiency was in 1989 by Fijen which included 9 males across 3 generations.[2] Out of the 46 family members in Fijen's study, the 9 who were affected were found to be more susceptible to fulminant meningococcal disease.[2]

Signs and Symptoms

As a protein involved in the function of the immune system, no external changes in physiology or aberrant physical characteristics are expressed by individuals possessing a properdin deficiency. However, individuals that have a properdin deficiency do have a heightened susceptibility to bacterial infections, most notably caused by bacteria within the Neisseria genus, though there have also been studied cases of individuals with recurrent pneumococcus bacteremia as a result of Streptococcus pneumoniae, another species of bacteria from an entirely different phylum.[2][3] Due to a heightened susceptibility to Neisseria bacterium, individuals with properdin deficiency are far more likely to succumb to bacterial infection such as meningitis, resulting in inflammation of the brain and spinal cord, which causes severe headaches, fevers, and neck stiffness, and may result in further development of other meningococcal diseases and extreme complications such as sepsis.[4] Individuals with properdin deficiency are also more likely to catch the sexually transmitted disease, gonorrhea, as it is also caused by Neisseria bacterium, resulting in swelling, itching, pain, and formation of pus on the mucous membranes, including, but not limited to, the genitals, mouth, and rectum.[5]

Diagnosis

As mentioned before, there are no external indications of properdin deficiency, and as such, properdin deficiency can only be reliably detected by lab tests.[2] In particular, the use of ELISA proves to be one of the most effective methods of detecting properdin deficiency, as the average healthy male is expected to show properdin antigen levels of around 128.0 ELISA units/ml, and obligate carrier females (recall that properdin deficiency is an X-linked disease) tend to show an average of 45.6 units/ml.[2] An individual with properdin deficiency should, by definition, show very little to no properdin antigen levels at all, as they do not possess the requisite gene to produce the protein.

Management

Pertaining to complement deficiencies, there is no cure and the treatments for complement deficiencies vary widely. The best course of action for management is usually for a patient to treat the complement deficiency as an immune deficiency and get immunized against the microbe associated with their deficiency (or best candidate).[6] As mentioned earlier, individuals with properdin deficiency are increasingly susceptible to Neisseria bacterium. Recent studies have indicated that individuals with properdin deficiency respond well when they are immunized with tetravalent polysaccharide meningococcal vaccine, which generates anti capsular antibodies and bactericidal anti-meningococcal activity against serotypes covered by the given vaccine.[7] The vaccine has been reported to lower the chances of reinfection by meningococci in individuals who have undergone the treatment, however the vaccine does not protect against group B meningococci and chemotherapy is recommended if full protection from all meningococci variants is desired.[7]

Epidemiology

Complement deficiencies are rare and currently not well characterized, so there has been difficulty detecting them. Currently, complement deficiencies only comprise approximately 2% of all primary immunodeficiency disorders. While the frequency of properdin deficiency has not been assessed worldwide, the risk of meningococcal infection in an individual with properdin deficiency has been calculated to be around 50%.[8]

References

- ^ van den Bogaard R, Fijen CA, Schipper MG, de Galan L, Kuijper EJ, Mannens MM (July 2000). "Molecular characterisation of 10 Dutch properdin type I deficient families: mutation analysis and X-inactivation studies". Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 8 (7): 513–8. doi:10.1038/sj.ejhg.5200496. PMID 10909851.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "OMIM Entry - # 312060 - PROPERDIN DEFICIENCY, X-LINKED; CFPD". www.omim.org. Retrieved 2022-03-23.

- ^ Sexton, Daniel J. "Invasive pneumococcal (Streptococcus pneumoniae) infections and bacteremia". www.uptodate.com. Retrieved 2022-03-24.

- ^ "Meningitis", Wikipedia, 2022-03-20, retrieved 2022-03-24

- ^ "Gonorrhea", Wikipedia, 2022-03-22, retrieved 2022-03-24

- ^ "Complement Deficiencies | Immune Deficiency Foundation". primaryimmune.org. Retrieved 2022-03-24.

- ^ a b Linton, S. M.; Morgan, B. P. (1999-11). "Properdin deficiency and meningococcal disease--identifying those most at risk". Clinical and Experimental Immunology. 118 (2): 189–191. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2249.1999.01057.x. ISSN 0009-9104. PMC 1905414. PMID 10540177.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ editor., Leung, Donald Y. M., 1949-. Pediatric allergy : principles and practice. ISBN 978-0-323-67462-1. OCLC 1202992443.

{{cite book}}:|last=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

External links