Kingdom of Valencia: Difference between revisions

mNo edit summary |

mNo edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{inprogress}} |

{{inprogress}} |

||

The '''Kingdom of Valencia''' was one of the component realms of the [[Crown of Aragon]] and, after its [[ |

The '''Kingdom of Valencia''' was one of the component realms of the [[Crown of Aragon]] and, after its [[dynastic union]] with the [[Crown of Castile]], it in turn became a component realm of the [[Kingdom of Spain]]. It was formally created in 1237 as the city of Valencia was taken from the [[taifa|moors]] in the course of the [[Reconquista]]. Kingdom of Valencia was ruled under the laws and institutions created by [[Furs of Valencia]] which gave it wide independence. It lasted until its abolishment by the [[House of Bourbon]] in 1707, by the means of the [[Nueva Planta decrees]]. |

||

==Conquest== |

==Conquest== |

||

Revision as of 09:24, 6 March 2007

![]() In progress

The Kingdom of Valencia was one of the component realms of the Crown of Aragon and, after its dynastic union with the Crown of Castile, it in turn became a component realm of the Kingdom of Spain. It was formally created in 1237 as the city of Valencia was taken from the moors in the course of the Reconquista. Kingdom of Valencia was ruled under the laws and institutions created by Furs of Valencia which gave it wide independence. It lasted until its abolishment by the House of Bourbon in 1707, by the means of the Nueva Planta decrees.

In progress

The Kingdom of Valencia was one of the component realms of the Crown of Aragon and, after its dynastic union with the Crown of Castile, it in turn became a component realm of the Kingdom of Spain. It was formally created in 1237 as the city of Valencia was taken from the moors in the course of the Reconquista. Kingdom of Valencia was ruled under the laws and institutions created by Furs of Valencia which gave it wide independence. It lasted until its abolishment by the House of Bourbon in 1707, by the means of the Nueva Planta decrees.

Conquest

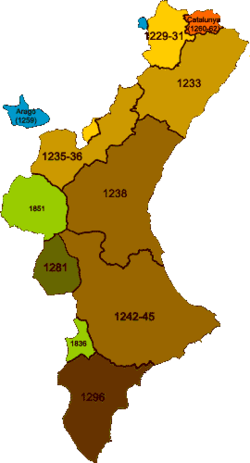

The conquest of what was going to be the Kingdom of Valencia started in 1232 when the king of the Crown of Aragón, James I, called Jaume I el Conquistador or the Conqueror, takes Morella mostly with Aragonese troops. Shortly after, in 1233, Burriana and Peñíscola are also taken from the Balansiya (Valencia in Arabic) taifa.

A second and more relevant wave of expansion takes place in 1237, when James I defeats the Moors from the Balansiya taifa and enters the city of Valencia on the 9th of October, which is regarded as the dawn of the Kingdom of Valencia.

A third phase starts in 1243 and ends in 1245, when it meets the limits agreed between James I and the heir to the throne of Castile, Alfonso, who would reign as Alfonso X. These limits were traced in the Almizra treaty between the Crowns of Castile and Aragon, which coordinated their Reconquista efforts to defeat the Moors by drawing their respective ambitions. The Almizra treaty fixed the south line of Aragonese expansion in the line formed by the villes of Biar and Busot, today in the North of the Alicante province. Everything South of that line, including what would be the Kingdom of Murcia, was reserved by means of this treaty for Castile.

The matter of the large majority of mudejar population lingered from the very beginning until they finally got expelled in 1609. Until that moment, they represented a complicated issue for the newly established Kingdom, as they were needed to keep the economy working, which inspired frequent pacts with local Muslim populations allowing their culture in various degrees of tollerance but, also, on the other side, they were deemed as menace to the Kingdom due to their lack of allegiance and their percieved conspiracies to bring the Ottoman Turks to their rescue.

There were indeed frequent rebellions from the Moor population against Christian rule, being the most threatening those headed by the Moor chieftain Al-Azraq. He led important rebellions in 1244, 1248 and 1276. During the first one he briefly regained Muslim independency for the lands South of the Júcar, but it was soon defeated. During the second revolt, king James I was almost killed in battle, but also was finally subjugated. During the third one, Al-Azraq himself was killed but his son would continue to promote Muslim unrest and local rebellions.

After the death of James I, his son James II called Jaume II el Just or the Just initiated in 1296 a final impulse of his army further southwards than the Biar-Busot pacts. His campaign is enters a fertile territory whose local Muslim rulers are binded by pacts with Castile which often raided the area to assert a sovereignity which, on the other side, was not stable but characterized by the typical skirmishes and ever changing alliances of a frontier territory.

James II campaign is successful to the point that he even conquers Orihuela and Murcia, well South of the initial border. What was going to be the final dividing line between Castile and the Crown of Aragón is agreed by virtue of the Sentencia Arbitral de Torrellas (1304) and the final Treaty of Elche (1305), which assignates Orihuela to the Kingdom of Valencia but hands Murcia to the Crown of Castile, thus drawing the Southern border of the Kingdom of Valencia which has been maintained to date.

At the end of the process, five taifas had been wiped out: Balansiya, Alpuente, Denia and Murcia.

Motives

Modern historiography see the conquest of Valencia under the light of similar Reconquista efforts by Castile: as a fight led by the King in order to gain new territories as free of possible of serfdom to the nobles but only accounting to the King, thus, enlarging and consolidating his power vs. the one of nobility (a growing trend which would substantiate in the Modern Era which left behind the Middle Age after 1492).

It is under this approach that the repopulation of the Kingdom is assessed today. The new Kingdom population was initially overwhelmingly Muslim and often subjected to revolts and the serious threat of being taken by any given fellow Muslim army put together for this purpose in the Maghreb.

The process by which the monarchy strived to free itself from any noble guardianship was not easy as the nobility hold still a big share of power and was determined to retain it as much as possible. This fact marked the Christian colonization of the newly acquired territories, ruled by the Lleis de Repartiments. Finally the Aragonese nobles were granted several domains but only managed to obtain the inland, mostly mountainous and sparsely populated parts of the Kingdom of Valencia, while the king reserved the fertile and highly populated lands in the coastal plains to free citizens and incipient bourgeois whose cities were given Furs or royal charters regulating civil law and administration locally, always accounting to the king.

This had linguistic consequences as the innerland was mostly repopulated by Aragonese (whose language, close to Castilian, soon merged with this into Spanish) while the coastal lands were mostly repopulated by Catalan speaking people from the Principality of Catalonia, whose Catalan was soon to evolve into Valencian, a distinctive variant of Catalan which has gained its own currency within the Catalan domain.

Another possibly primary driving force, but likely to be understated by modern historiography, was religious faith. In this regard, Pope Gregory IX recognized the fight as a Crusade and James I was known for being a devout king.

Splendour

The Kingdom of Valencia achieved its height during the early 15th century. The economy was prosperous and centered around trading through the Mediterranean, which had become a sea controlled by the Crown of Aragón, mostly from the ports of Valencia and Barcelona.

In the city of Valencia the Taula de canvis was created, being its functions in between the ones of a bank and those of a stock exchange market; altogether it boosted trading. The local industry, specially textile manufactures, achieved great development and the city of Valencia turned into a Mediterranean trading emporium where traders from all Europe worked. Perhaps the best symbol which summarizes this flamboyant period is the Silk Exchange, one of the finest European exemples of civil Gothic architecture and a major trade market in the Mediterranean by the end of 15th century and through the 16th as well.

Valencia was one of the first cities in Europe to install a movable type printing as per Gutenberg's design. It was Valencian authors such as Joanot Martorell or Ausias March who conformed the canon of classic Catalan literature.

Modern Era, the Germanies, and decay

The Kingdom of Valencia merges with the rest of territories of the Crown of Aragón and the Crown of Castile to form the modern Kingdom of Spain.

Habsburg Spain kings maintained the privileges and liberties of the territories and cities which formed the kingdom and its legal structure and factuality remained intact, still, the rising Spanish Empire, which had left behind its former status of peninsular kingdom to become a world power, shifts its focus to America and the fast developing northern and central Europe, where commerce has moved to, due to a diminishing Mediterranean trade which, in turn, was a consequence of the war with the Ottoman Turks and a fast growing Arab piracy activity. Altogether it represented a blow to the Kingdom of Valencia which has already been economically touched by the expulsion of the Jews in 1492.

Besides, locally bred social tensions provoked by the economic crisis erupted in the form of the Germanies revolt. A Germania (from germà "brother") was the name of the associations that the artisans of the different guilds had. The revolt they started in 1521, which led to civil unrest and bloody local clashes well into 1522, had several different causes, such as economic resent against the nobility and high bourgeois, a will to oust them from the city command and, also, a religious resent agains the Moors, which were closely associated to the nobles in their economic enterprises. This rebellion shares many traits and happens almost contemporarily to the one of the Comuneros in Castile.

As a result of the exhausted forces left by the clashes between nobles and high bourgeoisie vs. general populace and lesser bourgeoisie, the king used this power vacuum to enlarge his share of power and gradually diminish the ones of the local authorities; this meant that his requests for money in order to enlarge or consolidate the disputed possessions in Europe were each time more frequent, more imperative and, conversely, less reciprocated for the Kingdom of Valencia, just as they were elsewhere for the rest of the Spanish Kingdom territories.

Then the expulsion in 1609 of the mudejar population meant a final blow for the Kingdom of Valencia, as thousands of people were forced to leave, entire villages got deserted and the countryside lost its main labour force, which further deepened the economic crisis. Since the expulsion meant the lost of the free workforce for the nobility, themselves and the upper bourgeoisie had to turn to the king seeking for protection from the general populace, which meant that they had to renounce to their former check and balance role before the kings requests, which was one of the driving forces of the Kingdom's autonomy.

The Kingdom of Valencia as a legal and politic organization was finally terminated in 1707 as a result of the Spanish War of Succession. The local population mostly took side and provided troops and resources to Archduke Charles, who was arguably to maintain the legal status quo. His utter defeat at the Battle of Almansa, near the borders of the Kingdom of Valencia, meant its legal and politic termination, along with other autonomous parliaments in the Crown of Aragón, as the Nueva Planta Decrees were passed and the new House of Bourbon dynasty created a centralized Spain.