Richard Henry Dana Sr.: Difference between revisions

→Biography: Rearranged a bit |

→Biography: Rearrange and reword |

||

| Line 9: | Line 9: | ||

[[File:43_ChestnutSt_Boston_2010_e.jpg|thumb|left|100px|Dana's home on Beacon Hill, Boston]] |

[[File:43_ChestnutSt_Boston_2010_e.jpg|thumb|left|100px|Dana's home on Beacon Hill, Boston]] |

||

Dana seldom practiced law and instead focused on his literary career. As a literary critic between 1817 and 1827, he was the first American to write major critiques of [[Romanticism (literature)|Romanticism]], though his views were unconventional then.<ref name=Ferguson249>Ferguson, Robert A. ''Law and Letters in American Culture''. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1984: 249. ISBN 0-674-51465-3</ref> In a review of the poetry of [[Washington Allston]], he noted his belief that poetry was the highest form of art, though it should be simple and must avoid [[didacticism]].<ref>Ferguson, Robert A. ''Law and Letters in American Culture''. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1984: 250. ISBN 0-674-51465-3</ref> |

Dana seldom practiced law and instead focused on his literary career. As a literary critic between 1817 and 1827, he was the first American to write major critiques of [[Romanticism (literature)|Romanticism]], though his views were unconventional then.<ref name=Ferguson249>Ferguson, Robert A. ''Law and Letters in American Culture''. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1984: 249. ISBN 0-674-51465-3</ref> In a review of the poetry of [[Washington Allston]], he noted his belief that poetry was the highest form of art, though it should be simple and must avoid [[didacticism]].<ref>Ferguson, Robert A. ''Law and Letters in American Culture''. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1984: 250. ISBN 0-674-51465-3</ref> Dana also criticized the [[Transcendentalism]] movement. He wrote, "[[Ralph Waldo Emerson|Emerson]] & the other Spiritualists, or Supernaturalists, or whatever they are called, or may be pleased to call themselves... [have] madness in their ''hearts''".<ref name=Ferguson249/> Dana was a member of the [[Anthology Club]]; he and others in the club founded the ''[[North American Review]]''.<ref>Brickhouse, Amanda. ''Transamerican Literary Relations and Nineteenth-Century Public Sphere''. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2004: 151. ISBN 0-521-84172-0</ref><ref>[http://books.google.com/books?id=0DwEAAAAYAAJ Encyclopædia Britannica], 11th ed. 1910</ref> in 1817 as an outlet for his criticism, though his opposition with standard conventions lost him his editorial control of it.<ref>Haralson, Eric L. ''Encyclopedia of American Poetry: The Nineteenth Century''. Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn Publishers, 1998: 115–116. ISBN 1-57958-008-4</ref> Though some of his criticisms were controversial at the time, by 1850, his opinions were widely conventional. As he wrote at the time, "Much that was once held to be presumptuous novelty... [became] little better than commonplace".<ref name=Ferguson249/> |

||

As a writer of fiction, Dana was an early practitioner of [[Gothic literature]], particularly with his novel ''Paul Felton'' (1822), a tale of madness and murder.<ref>Ferguson, Robert A. ''Law and Letters in American Culture''. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1984: 252. ISBN 0-674-51465-3</ref> The novel has also been called a pioneering work of psychological realism alongside works by [[William Gilmore Simms]].<ref>Pfister, Joel. ''The Production of Personal Life: Class, Gender, and the Psychological in Hawthorne's Fiction''. Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press, 1991: 52–53. ISBN 0-8047-1948-9</ref> Nevertheless, Dana had difficulty supporting his family through his writing, which earned him only $400 over 30 years.<ref>Sullivan, Wilson. ''New England Men of Letters''. New York: The Macmillan Company, 1972: 99. ISBN 0-02-788680-8</ref> In 1849, he was elected into the [[National Academy of Design]] as an Honorary Academician. |

As a writer of fiction, Dana was an early practitioner of [[Gothic literature]], particularly with his novel ''Paul Felton'' (1822), a tale of madness and murder.<ref>Ferguson, Robert A. ''Law and Letters in American Culture''. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1984: 252. ISBN 0-674-51465-3</ref> The novel has also been called a pioneering work of psychological realism alongside works by [[William Gilmore Simms]].<ref>Pfister, Joel. ''The Production of Personal Life: Class, Gender, and the Psychological in Hawthorne's Fiction''. Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press, 1991: 52–53. ISBN 0-8047-1948-9</ref> Nevertheless, Dana had difficulty supporting his family through his writing, which earned him only $400 over 30 years.<ref>Sullivan, Wilson. ''New England Men of Letters''. New York: The Macmillan Company, 1972: 99. ISBN 0-02-788680-8</ref> In 1849, he was elected into the [[National Academy of Design]] as an Honorary Academician. |

||

Revision as of 19:50, 30 June 2015

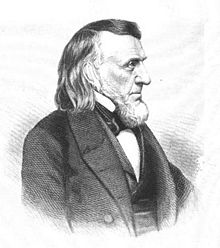

Richard Henry Dana Sr. | |

|---|---|

| |

| Signature | |

Richard Henry Dana, Sr. (November 15, 1787 – February 2, 1879) was an American poet, critic and lawyer. His son, Richard Henry Dana, Jr., also became a lawyer and author.

Biography

Richard Henry Dana was born in Cambridge, Massachusetts on November 15, 1787, the son of Federalist judge Francis Dana.[1] He graduated from Harvard College and became a lawyer. He married Ruth Charlotte Smith and they had four children including Richard Henry Dana, Jr. Despite having graduated from there, Dana accused Harvard of smothering genius, and believed that the minds of poets were more insightful than the general community.[1]

Dana seldom practiced law and instead focused on his literary career. As a literary critic between 1817 and 1827, he was the first American to write major critiques of Romanticism, though his views were unconventional then.[2] In a review of the poetry of Washington Allston, he noted his belief that poetry was the highest form of art, though it should be simple and must avoid didacticism.[3] Dana also criticized the Transcendentalism movement. He wrote, "Emerson & the other Spiritualists, or Supernaturalists, or whatever they are called, or may be pleased to call themselves... [have] madness in their hearts".[2] Dana was a member of the Anthology Club; he and others in the club founded the North American Review.[4][5] in 1817 as an outlet for his criticism, though his opposition with standard conventions lost him his editorial control of it.[6] Though some of his criticisms were controversial at the time, by 1850, his opinions were widely conventional. As he wrote at the time, "Much that was once held to be presumptuous novelty... [became] little better than commonplace".[2]

As a writer of fiction, Dana was an early practitioner of Gothic literature, particularly with his novel Paul Felton (1822), a tale of madness and murder.[7] The novel has also been called a pioneering work of psychological realism alongside works by William Gilmore Simms.[8] Nevertheless, Dana had difficulty supporting his family through his writing, which earned him only $400 over 30 years.[9] In 1849, he was elected into the National Academy of Design as an Honorary Academician.

He lived on Chestnut Street in Boston's Beacon Hill neighborhood, ca.1840s-1870s.[10]

Dana died on February 2, 1879, and was buried in the family plot at the Old Burying Ground next to the First Parish in Cambridge.

Further reading

Works by Dana

- An oration, delivered before the Washington benevolent society at Cambridge, July 4, 1814. Printed by Hilliard and Metcalf, 1814.

- The Idle Man. v.1 (1821-1822)

Works about Dana

- Hunter, Dorren M. Richard Henry Dana, Sr. Twayne Publishers, Inc., 1987.

References

- ^ a b Haralson, Eric L. Encyclopedia of American Poetry: The Nineteenth Century. Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn Publishers, 1998: 115. ISBN 1-57958-008-4

- ^ a b c Ferguson, Robert A. Law and Letters in American Culture. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1984: 249. ISBN 0-674-51465-3

- ^ Ferguson, Robert A. Law and Letters in American Culture. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1984: 250. ISBN 0-674-51465-3

- ^ Brickhouse, Amanda. Transamerican Literary Relations and Nineteenth-Century Public Sphere. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2004: 151. ISBN 0-521-84172-0

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica, 11th ed. 1910

- ^ Haralson, Eric L. Encyclopedia of American Poetry: The Nineteenth Century. Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn Publishers, 1998: 115–116. ISBN 1-57958-008-4

- ^ Ferguson, Robert A. Law and Letters in American Culture. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1984: 252. ISBN 0-674-51465-3

- ^ Pfister, Joel. The Production of Personal Life: Class, Gender, and the Psychological in Hawthorne's Fiction. Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press, 1991: 52–53. ISBN 0-8047-1948-9

- ^ Sullivan, Wilson. New England Men of Letters. New York: The Macmillan Company, 1972: 99. ISBN 0-02-788680-8

- ^ Boston Directory. 1848, 1852, 1861, 1873

External links

- WorldCat

- Richard Henry Dana, Sr. at Lawyers and Poetry