De homine

" De homine " ( French "Traité de l'homme" , German treatise on man ) is a medical-philosophical treatise by René Descartes .

René Descartes was not only a well-known philosopher, but also a scientist, which he makes clear , among other things, in the fifth part of his " Discours de la méthode ". He has also specialized in the field of human anatomy and physiology, and in the “treatise” he particularly deals with the function of the heart.

content

Descartes already summarizes important theses in this part, but his exact conception of man can be found in his book “Traité de l'homme - About man”, a detailed treatise on anatomy, published after his death.

Descartes was a representative of rationalism and especially of mechanicism . Mechanicism is the name of his thesis that man, animals and the universe correspond to the essence of a machine. In the “Traité de l'homme”, Descartes mainly deals with the fact that man is like a machine, “(his) heart (works like an oven)” and that he was created by God.

Descartes first explains in detail the blood circulation and the function of the circulating blood in our brain. He compares the circulation of the blood to a continual flow that can drive various machines. In addition, he goes into detail on the path of blood to the heart, describing the individual functions of the veins and arteries, as well as the "arterial vein" or the "venous artery". He also explains the path of the vena cava, the most important and largest vein that reaches the heart and "(...) forms the trunk of a tree, the branches of which are all other veins in the body (...)." It takes from the smallest Body parts break up the deoxygenated blood and transport it to the heart. Now the left ventricle of the heart opens and lets in a drop of blood, which is expanded by the heat and more blood drips into the heart. The blood is thus warmed up and enriched with oxygen. Now it leaves the right ventricle through the main artery and spreads in the body. Descartes still clarifies the question of why the arteries, which can hold all the blood that flows into them from the heart, and cannot burst or the like, which would simultaneously lead to the drying up of the blood in the veins. It describes a "constant circulation" of the blood that flows into the arteries and into small tributaries that become small branches of the veins and thus guide the blood back into the heart, which then flows back into the tributaries. Descartes also explains all other functions of our organs, such as stomach, eye, etc. with the entire circulation of the blood. He substantiates his thesis by explaining how the blood flows into the veins in the stomach and that the stomach can only produce gastric acid. when the blood flows through the heart over and over again 100 - 200 times a day, where it receives new oxygen and new warmth and transfers this to the remaining extremities and organs. Then he proves the efficiency of our "spirits" with the blood circulation. He believes that the warmest and "liveliest" blood flows into our brains to breathe life into our rational mind, to carry out every single movement down to the smallest pore and to awaken every single one of our senses. He claims that the spirits are "like a very fine breath, or rather like a very pure and very lively flame (...)" that fill nerves and muscles with warmth and stimulate them to move.

At this point he draws the first comparison of humans with automatons and machines. Because when our spirits carry out our movements such as breathing or blinking, without our human will evaluating these movements individually and approving them , this must be like a movement of an automaton (derived from the ancient Greek αὐτόματος automatos "occurring by itself").

Descartes writes:

“This (the explanations of the movements of the spirits) will in no way come as a surprise to those who know how many different automatons or mobile machines can produce the dexterity of humans, and this in comparison to the large number of bones, muscles, nerves, arteries , Veins, and all the other parts that are in the body of every animal using very few pieces; and who will regard this body as a machine which, made by the hands of God, is incomparably better constructed and has admirable movements in it than any that can be invented by men. "

With this he says that man is a machine that God created. He also describes the difference between animals and humans, both of which are machines created by God. He says that the only two differences between animals and humans are that humans have the language, and even if an animal were incredibly similar to us humans, it couldn't, like humans, string words together and put them in a logical sequence put together. Even the “dullest person” can combine words into a sentence, which makes him a person and the animal an animal. The second difference is that although there may be some animals who perform various actions better than we do, animals only “act according to the disposition of their organs” and not according to their reason. Man is a rational being, whose soul follows the path of reason and does not allow man to act solely on instincts. This brings Descartes straight to the soul, which for him consists of a different nature that is independent of the body, since different types of animals must have a different soul, because they all have different organs and act differently according to the disposition of the latter and humans, since they all have different characters and each person is an individual. However, the souls of animals and humans are completely different again. The soul, which is now independent of the body, cannot die as soon as the body of the soul bearer dies and is consequently immortal.

Descartes knew and valued Galileo's works and was informed of the trial against him by the church . So he preferred not to publish his scientific treatise "Traité de l'homme", but to integrate a summary of his theses into the "Discours de la Méthode" in order to avoid being indexed by the Church.

Given that Descartes did his research on real people and found things that had not yet appeared, he did not know how the Church would react. After all, it was considered impossible to examine corpses for their organs and to re-enact their functions instead of burying them in peace and letting them rest. Neither was it desirable to look for evidence in humans that showed that humans are made up of chemical processes and atoms. Descartes believed in God, but thought it safer not to publish his book. The reasons for his cautious approach can be found in the " Discours de la méthode ":

“But because for this I would have to speak about questions that are disputed among the scholars, and I do not wish to argue with them, I consider it best to refrain from this and only to say in general what the questions are to let wiser people decide whether it is appropriate to inform the public more precisely. "

But Descartes had not written his treatise for nothing. He wanted to publish it, just looking for the right time. And this one was shortly before his death. In the fifth part, in which his treatise on man is summarized, he had only written a general summary of his theses in a summarized form in his " Discours de la méthode " out of fear :

“But because I have tried to explain the most important of them (important truths about man) in a treatise, which some considerations prevent me from publishing, I cannot make it better known than here summarizing what it contains. Before I wrote, I intended to include everything I thought I knew about the nature of material things. But just as a painter cannot depict all the different outer sides of a spatial structure equally well on a flat surface and only selects one of the main ones, which he puts in the light, the others in shadow and only lets them appear as far as they are in considering the main ones, I tried, for fear of not being able to accommodate everything I had in my thoughts in the course of my presentation, only to explain in great detail what I understood about light; [...] "

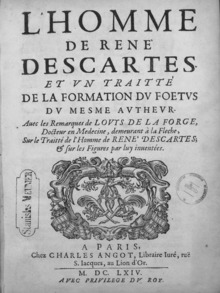

The treatise was not brought to the public until 1662. At this point Descartes had been dead for 12 years.

Individual evidence

- ^ First edition of De homine from 1662 (Descartes died in 1650)