Discours de la méthode

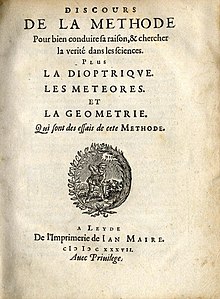

The Discours de la méthode , with the full title Discours de la méthode pour bien conduire sa raison et chercher la verité dans les sciences ( Eng . "Treatise on the method of making good use of reason and seeking the truth in the sciences"), is a philosophical and autobiographical work by the French philosopher René Descartes .

It first appeared anonymously in French in 1637 in Leiden and was therefore also accessible to philosophical laypeople. In 1656 a Latin version followed, which was published in Amsterdam .

Plant context

The discours includes Descartes' exploration of skepticism and the Aristotelianism of scholasticism . Based on a general doubt about traditional truths, but also about one's own judgment, Descartes' goal is to find irrefutable true sentences. Framed by descriptions of his intellectual autobiography, Descartes describes in detail one of the earliest programs for scientific nature research. The Discours is therefore considered to be one of the origins of the philosophy of science .

The Discours forms a methodological preface to three natural philosophical treatises by Descartes, which were edited together with him: La Dioptrique , Les Météores and La Géométrie . These investigations, which deal with the refraction of light, celestial phenomena and analytical geometry ( the Cartesian coordinate system is presented in the geometry ), already represent an application of this procedure: Through mathematical modeling, the natural phenomena are determined with the help of general rules, which are based on measurement and step by step Calculation and compelling conclusions are applied to the individual case.

Together with the Meditationes de prima philosophia , the Principia Philosophiae and the Regulae ad directionem ingenii , the Discours forms the basis of the form of rationalism known as Cartesianism .

The famous quote “Je pense, donc je suis” (Eng. “I think, therefore I am”) comes from Part IV of the Discours de la méthode. The " Cogito ergo sum ", however, comes from § 7 of the Principia Philosophiae of 1644.

construction

The discourse itself consists of six parts, the classification of which Descartes suggests in his foreword.

- Reflections on the Sciences

- Main rules of the method

- Some moral rules

- Foundations of Metaphysics

- Questions of natural philosophy

- Reasons that made the author write

In the original, in contrast to modern editions, there are no subheadings. Descartes chose the form of an autobiography for the Discours , but in fact it is a rationalist program writing: Descartes describing his own intellectual career provides reasons and describes steps to distance himself from the prejudices of his time and to philosophize rationally.

Summary

Reflections on the Sciences

Descartes describes the initial situation: In all sciences, but also with regard to morality and religion, the inquisitive person encounters numerous competing theories without their rival validity claims being able to be decided. Only in mathematics does there seem to be consensus on the validity criteria, so that the scientific community competes for the priority of discoveries and not for alternative systems.

Main rules of the method

Descartes bases the necessity of a new beginning on this negative finding: the historically handed down, contradicting form of the sciences is to be replaced by a systematic one. The system should make it possible to identify contradictions and gaps more quickly. Descartes formulates four rules for the new justification:

- Accept as true only what is beyond doubt certain.

- Break each question down into sub-problems and simple questions that can be decided with certainty.

- Build up the knowledge in turn from the answers to these simple questions and assume such a simple structure for all complex questions.

- Check these elements to see if they form a complete order.

Descartes sees this problem-solving strategy already implemented in ancient geometry.

Some moral rules

With these rules, problems can be solved scientifically, but they require time to analyze and answer the elementary questions. Until a worldview emerges that can also have a guiding function, Descartes recommends a provisional morality based on a balanced conformity to the environment that avoids extremes. The skeptic Montaigne had recommended a similar morality . Descartes declares such skepticism to be preliminary - the rules are intended to be able to truthfully answer all questions, including normative ones.

Foundations of Metaphysics

Descartes' goal is therefore the "investigation of the truth". He approaches this goal methodically in such a way that he initially rejects anything that can be doubted. Descartes first states that external experience, conclusions, and even phenomenal consciousness do not meet this criterion:

Since the senses can sometimes deceive us, they are not certain. He also states that formally correct logical conclusions of traditional syllogistics can still lead to incorrect results. So they are not certain either. Thirdly, it is even possible that we have the same thoughts in the dream as in the waking state. From this he draws the conclusion that all contents of consciousness can just as well be illusions.

The formal act of thinking (here doubting) itself is excluded from this reservation. Doubting presupposes a doubting subject, thinking a subject who thinks. This is expressed in the famous formula "I think therefore I am" ("Je pense, donc je suis"). (In the Principia philosophiae (§ 7) it says: Cogito, ergo sum .)

From the certainty that consciousness has about its existence, he makes an example of how certain a truth has to be for us in general. All judgments about things that claim truth must be evident to us in a similar way and become evident to us as the sentence: “I think, therefore I am”.

Certain facts can only become clear and evident to the conscious mind if it is able to recognize these facts as clear and distinct (meaning: determined by properties and distinguishable from others, clara et distincta ) and that means their special quality to perceive against the ordinary doubts. So it has the ability to distinguish certainty from doubt. Descartes suspects that this ability comes from the fact that the consciousness has an idea of perfection from the start, which forms the yardstick or the evaluation criterion in order to also be able to classify the contents of consciousness: knowledge and certainty are more perfect than doubt. The idea of perfection comes from God; but not in such a way that he implanted it as a single idea in us, in our consciousness, but rather so that the consciousness, when it perceives God, must also grasp perfection as an attribute of God (and then in can be used in other contexts).

Or the other way around: Since the concept of perfection is (provable) present in our consciousness, Descartes draws the conclusion that God necessarily exists - and indeed exists recognizable for us, because how else should consciousness come to this concept and how without it in be able to see anything at all? The fact that the consciousness is able to recognize something is shown by the evidence of the sentences: “I think, therefore I am” and “A perfect being must exist”.

In the following section, these two results from the fourth and fifth sections are now linked: What we clearly understand is true. God is the guarantee for the truth.

So: what we grasp clearly and precisely comes from God. In the last section Descartes takes up the dream argument from the beginning. The first conclusion was that all knowledge of reality is doubtful because we - as in a dream - could be mistaken. Now, however, since the existence of a true and perfect God seems to be derived from the concept of perfection, God can be postulated as a condition for the possibility of true knowledge, although the imperfection of man must be admitted as the cause of false knowledge.

Questions of natural philosophy

In this section Descartes demonstrates his method with two examples: On the one hand, he recognizes that the blood circulation was one of the first Harvey's discoveries, but not his conception of the pumping function of the heart, but claims that the movement of the blood is controlled by its warming and heat expansion On the other hand, he redefined the difference between humans and animals. While animals are biological automatons, man shows that he has a soul that causes his body ( res extensa ) to move beyond natural determination. Above all, speaking is an expression of thinking, which, according to Descartes, is a state of soul substance ( res cogitans ).

Reasons that made the author write

Although he is already a respected scholar, Descartes realizes that his achievements did not outgrow a superior intellect, but rather stem from his ability not to be blinded by overdetermination . Furthermore, he proceeds step by step, whereby each step must be clear and distinct. In this publication he presents his analytical method and shows a wide range of its applications and capabilities.

Descartes raises the question of how reliable knowledge can be gained in philosophy, science, medicine and ethics.

The result of his considerations is that, on the one hand, a secure foundation is required on which all knowledge can build. On the other hand, a method is required in order to be able to advance securely from the foundation to further knowledge. The result is a hierarchy of sciences or areas of knowledge. So philosophy is the foundation (or the root) of all knowledge. Physics builds on this as a trunk, through which one can finally come to reliable knowledge of medicine, mechanics and morality. Since the right ethics can only be found at the end of the process, Descartes also shows the need for a provisional morality for the transition period.

See also

Translations

- From the method (Discours de la méthode). Newly translated from French and edited with notes and indexes. from Lüder Gäbe. Hamburg 1960 (= Philo. Biblio. Volume 15).

Web links

- Full text on wikisource

- Discours de la méthode (1637), édition Adam et Tannery, 1902. (PDF, 80 pages, 362 kB)

- Treatise on the method full text in German translation by Kuno Fischer (1863)

- Fourth section of the discourse in German translation

- Discours de la méthode at Zeno.org . in German translation by JH v. Kirchmann , PhB 25 [1], Berlin 1870.

Individual evidence

- ^ René Descartes: La Dioptrique , ed. V. Cousin

- ^ René Descartes: Les Météores , ed. V. Cousin

- ↑ René Descartes: La Geometry

- ↑ René Descartes: Treatise on the method / preface , German by Julius von Kirchmann (1870), pp. 19-20.

- ↑ cf. the representation of Emerich Coreth and Harald Schöndorf : Philosophy of the 17th and 18th centuries. Retrieved March 20, 2011 . , Stuttgart: Kohlhammer 1983, p. 34.

- ↑ cf. the representation of Emerich Coreth, Harald Schöndorf: Philosophy of the 17th and 18th centuries. Retrieved March 20, 2011 . , Stuttgart: Kohlhammer 1983, p. 34.

- ^ W. Bruce Fye: Profiles in Cardiology - René Descartes , Clin. Cardiol. 26, 49-51 (2003) , PDF 58.2 kB.