Decentralization theorem

The decentralization theorem was developed by Wallace E. Oates (1972) and is an approach to the economic justification of federal forms of government . It considers u. a. the question of whether the provision of public goods with a Pareto-efficient allocation within the public sector and as close as possible to the preferences of citizens should be centralized or decentralized. In application, this theorem is an important economic foundation for the principle of subsidiarity .

The theorem

A decentralized provision is always more efficient than (or at least as efficient as) a central one, if

- the preferences of the citizens differ between the administrative units (interregional) but not within one administrative unit (intraregional),

- there are no external effects , i.e. the benefits and costs of the provision are limited to the spatial area of the respective administrative unit, and

- the marginal and average costs are the same for each output level in each region, regardless of whether the provision is centralized or decentralized (no economies of scale).

Representation with different regional preference structures

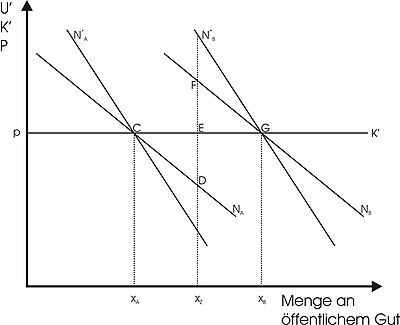

The assessment with regard to the efficiency criterion can be illustrated with the help of the pension concept (see Figure 1):

Let there be interregional and different demand curves for a public good with intraregional same preferences. be the marginal costs of provision (these correspond to the tax price and are assumed to be constant for simplicity). In the case of decentralized provision, the amount would result for region A and the same for region B, the amount .

If a central government were to provide a uniform level of supply, it would choose, for example, the level that lies between the output levels preferred in the individual administrative units. With regard to the preferences of the individuals in region A, there would be an oversupply, with regard to the preferences of the individuals in region B, there would be an undersupply. Accordingly, there is a loss of prosperity in both areas. These are expressed for region A by the area CED, in which the (tax) price of the public good is above the marginal willingness to pay. At the same time, the individuals in Region B suffer a loss of welfare equivalent to the area EFG, because their marginal willingness to pay is higher than the current price. Obviously, the loss of welfare does not go away even if the central government chooses a different output level . Only its distribution across the regions would change.

A decentralized provision makes it possible to avoid welfare losses because regional differences in the preferences of the citizens can be taken into account.

It also shows that the welfare losses in the case of central provision of public goods increase with increasing divergence of the regional preference structures (corresponding demand curves would be further apart). Furthermore, the welfare losses are greater the more price inelastic the demand for the public good under consideration is (demand curves or ). The price elasticity of demand is likely to be higher the more independent administrative units there are.

Representation with different regional cost structures

Different regional cost structures can also make decentralized provision more efficient than centralized. Such cost differences can be caused by different production and environmental conditions in individual regions (see Figure 2).

For the sake of simplicity, it is assumed in the figure that the preferences of citizens for a specific public good are the same across regions. However, different supply costs (different marginal cost curves) lead to the regionally different optimal output levels or . The marginal cost curve applies to central provision (for example due to a mixed calculation) . The level of provision would then come about, which would again result in welfare losses in the amount of CDE and EFG.

Overall, there must be a valid reason for the central provision of a public good that explains why the welfare gains (or welfare losses avoided) associated with decentralized provision are not realized.

criticism

Sometimes it is suggested that central provision could also take place with regionally different output levels. This is possible in principle. The objection to this, however, is that, because of their greater proximity to citizens, regional governments can find out more about their preferences and more cheaply than a central government can.

More serious, however, are two further points of criticism, namely the existence of economies of scale and interregional external effects, which are excluded when deriving the decentralization theorem.

Economies of scale

Constant marginal and average costs are rare phenomena. Much more often, there are decreasing or increasing average costs (e.g. due to economies of scale or returns of scale). In the case of pure public goods, for example, there is no rivalry in consumption, so the marginal costs for an additional user are zero. In this case, the average costs drop permanently with increasing production volume, which is why a single supplier can offer the goods in question cheaper than several suppliers could (cf. natural monopolies). But even in a less extreme case, in which falling average costs only lead to an oligopolistic market structure, a choice between centralized and decentralized provision is not obvious, because the optimal community sizes determined according to minimum average costs (comparable to optimal company size) do not have to match those which are based on the preference differences of individuals. In this context, there is a trade-off between proximity to preferences and minimizing costs. However, this argument can be countered by the fact that an administrative unit does not need to produce the public good itself. For example, she can team up with others and have the goods produced privately (often happens in the area of waste disposal, for example).

Interregional externalities

As a rule, the scope of a public good and the spatial extent of an administrative unit do not match, which is why interregional external effects occur, which lead to inefficiencies and make corrections necessary, as explained in the following figure:

Administrative unit A produces a public good with positive external effects at constant marginal costs . If the administrative unit is based only on the marginal utility of its citizens ( ), then it provides the amount . In this way, however, the optimal level for society as a whole is missed, which, taking into account the positive external effects, is. However, A could try to persuade administrative unit B to make compensation payments through negotiations (cf. Coase theorem ) in order to achieve an optimal level of care for society as a whole.

If the external effects affect many administrative units - which makes a negotiated solution difficult - then a central government can internalize the external effects through financial allocations. It can thus reduce the marginal costs of administrative unit A , which leads to the provision of the optimal output for society as a whole . Alternatively, it could also take over the provision of the relevant public good itself.

In general, it can be assumed that the extent of interregional external effects due to inefficient allocation of public goods is greater the smaller the administrative units responsible for supply are. In individual cases, however, the welfare effects will depend on the specific properties of the good in question.

See also

literature

- Edling, Herbert (2001): The state in the economy. Basics of public finance in an international context. Publisher Franz Vahlen, Munich

- Oates, Wallace E. (1972): Fiscal federalism. New York, HBJ.

- Blankart, Charles B. (2003): Public Finances in Democracy. 5th edition, Munich, Verlag Franz Vahlen.