Film drive

The film drive is the central mechanical unit of the basic film equipment camera , copier and projector , i.e. the heart of cinematography . The pioneers' film drives are solutions to the task of repeatedly driving (perforated) film strips forward a certain distance and stopping them for exposure or making them usable in another way. There are some film drive ideas that have been in use almost unchanged for a long time.

construction

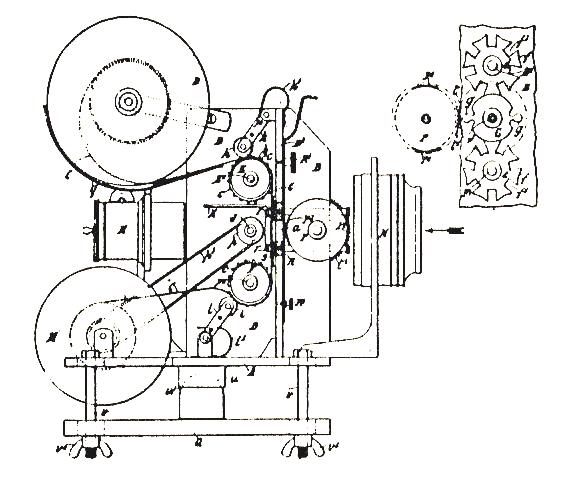

Birt Acres (1854–1918) gave an illustration of a mechanism with two so-called star wheels. The small drawing at the top right shows how on the other side the central cam wheel c advances the star wheels twice with each revolution. On the shafts of the star wheels sit toothed drums, which drive the film forward picture by picture:

This is followed by the condenser, two-winged drum diaphragm, film and lens starting from the arrow .

Examples of film drives

The so-called bat mechanism is one of the oldest film drives. It was introduced by Georges Emile Joseph Démény in 1893, the "came Démény", and tried out again and again. The reason why the racket projectors have disappeared is due to the splicing of the composite colored copies of silent films, which have often been downright broken. Jean-Aimé LeRoy created the first American bat projector in 1893–94.

Film viewers and cutting tables are generally provided with continuous film drives. The light coming from the film falls through a glass prism with an even number of parallel, flat end faces, whereby the prism rotates twice as fast as the film moves past it. This results in the so-called optical compensation of the image migration. Simple film viewers have built-in quadruples. Expensive processing tables have prisms with 12 to 20 surfaces. They work practically flicker-free. The Mechau -Apparat and the Perfectone-Unitor are projectors with a continuous film drive and mirrors . State of the art: 1900

The pulley in connection with a star wheel, special case Maltese cross, occurs in practically all cinema projectors . The Maltese cross locking mechanism is state of the art in 1896 since Oskar Messter's contribution to a flywheel on the pin shaft .

The ratchet gripper can be recognized by its beveled tooth and by the fact that it gives way when you push it in. Well-known 35 mm film cameras with this drive are the Pathé from 1896 and the Eclair Caméflex from 1946. Among the 16 mm film cameras, the Canon Scoopic is known as a ratchet gripper device (1965). Most Super 8 cameras have the ratchet gripper.

The controlled gripper is known from the Domitor Lumière. The state-of-the-art sewing machine technology was adopted in 1894 .

A remarkable film drive is realized in “ Debrie Grande Vitesse ”. This camera enables manual recordings of up to 240 images per second with a controlled double gripper, i.e. with a two-tooth gripper in both rows of holes. A pair of locking pins fixes the film for exposure on both sides of the image window . Inventor: Emile Labrély, patents 1919 and 1920

Another principle of the film drive can be found in wave loop mechanisms, for example the "rolling loop mechanism" of the IMAX projectors . The material is not transported linearly, but in wave-shaped loops that arise one after the other, each time causing an offset of one film step on the picture window , and then disappearing again one after the other.

Technical order

The known film drives can be classified, one class being different from the others in that the film runs through uninterruptedly. In this class 0 (zero), a stationary moving image is achieved with rotating mirrors, prisms or lenses.

In class 1 there are simple elements that move the friction-braked film, such as pulley, eccentric (beater), gripper and the like. a. m.

In class 2 there are additional positioning devices for fixing the film, such as resilient tongues, locking pins (locking grippers) and the like. a. m. The film has only minimal friction.

In class 3 there are dowel pins firmly connected to the picture window, on which the film is placed and removed again.

Materials and designs

Brass, bronze and steel are found among the pioneers. With the First World War, the transition to almost complete use of steel takes place. Hardened steel is increasingly being used, nitrided steel, for example in the handheld cameras from Bell & Howell, and occasionally ceramic. In the professional camera, the film drive is designed as a unit that can be easily separated from the camera body, as is the case with Bell & Howell Standard and Leonard-Mitchell.

Copier machines are sometimes given very robust mechanics because they are increasingly being operated by unskilled people. For decades, projectors have been designed with heavy cast housings and solid steel gears and almost all of them have plain bearings with oil grooves. While US projectors only have steel film webs to this day, other manufacturers have been working with plastics since the 1950s. Accordingly, the film copies have grown in the new world, but not in the old one.

Services

The film drive that works most precisely to this day is the one that became known with the professional cameras of Bell & Howell Co. in 1909 and 1911. The film is set with its perforation on conical dowel pins. There is no game. The press fit brings the accuracy of the hole shape to bear, which repeatedly varies by less than a thousandth of a millimeter. Similar dowel pin mechanisms exist in the rackover camera from Leonard (1917), the Auto Kine Camera from Newman & Sinclair (1927) and the Newman-Sinclair P 400 (1962).

The Maltese cross lock in oil capsule performs billions of separate turns of the pulley in the course of its life. As an illustration, it should only be mentioned that 100 minutes of sound film make 144,000 switchings.

With the fastest intermittent film drives, you can get 500 frames per second, in exceptional cases up to 1000. Film with a polyester carrier is used.

So-called quick switches are film drives for portable narrow and small film projectors. One tries to increase the amount of light by expanding the light phase compared to the dark phase. The prerequisite for this is that as little film mass as possible is moved in a relatively long but smooth film channel. The disadvantage of these drives must be seen in the fact that film protection is in question if there is a lack of device care.

The rolling loop film drive, as used by IMAX (Image Maximization Systems Corp.), transports the film material in a wave-like motion. It is equipped with a vacuum picture window so that the relatively large piece of film lies against a ground and polished glass in the picture window, a field flattener , despite the heat of the lamp . In addition, 4 locking grippers hold the current film image in order to ensure optimal image stability.

With the Mitchell NC , 1927, and the Sound Camera, 1932, there was a new film drive in which the effect of the transport and locking grippers is overlapping. The film is therefore always run. The drive is nimble, quiet and, like the Bell & Howell 2709, can be removed as a unit from the camera.