Kaldor-Hicks criterion

The Kaldor-Hicks criterion (after Nicholas Kaldor and John Richard Hicks ) is a prosperity criterion , which is based on the idea of a potential interpersonal compensation (compensation) in the event of changes in prosperity. It therefore belongs to the compensation criteria , such as the Scitovsky criterion or the criteria according to Samuelson and Gorman. In contrast to the Pareto criterion , in which changes in an economic situation can only be assessed from the point of view of prosperity if there are no opposing individual changes in prosperity (lack of interpersonal comparison of benefits), compensation criteria also try to evaluate changes in welfare in society as a whole, in which the welfare of individual individuals increases while the other sinks. The criteria mentioned try to offset gains and losses in prosperity against each other.

presentation

According to the Kaldor-Hicks criterion, an increase in prosperity is always spoken of in society as a whole if the individuals who experience an increase in prosperity as a result of the change in the economic situation can fully compensate those individuals who suffer loss of welfare and ultimately still retain part of the original gain in prosperity.

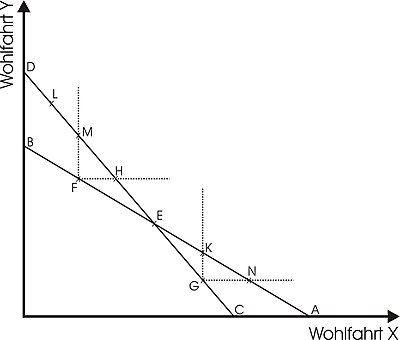

The following figure serves to illustrate the criterion:

Shown are the utility possibility curves of two individuals X and Y through the routes AB and CD, respectively. In the initial situation, the distribution situation F is relevant on the utility possibility curve AB. After the change in the economic situation, the utility possibility curve CD applies and the corresponding distribution situation is L. According to the Pareto criterion, the new situation cannot be compared with the old one with regard to the welfare aspect, because while the welfare of the individual Y has increased, that of the individual is X decreased. According to the Kaldor-Hicks criterion, however, the change in the distribution situation increases the welfare of society as a whole, because based on situation L, the real allocation of the new bundle of goods could take place in such a way that point M is reached, at which the welfare of X compared to the situation in F. is unchanged while the welfare of the Y has increased. Accordingly, all changes in the real allocation would increase welfare for society as a whole, at which a point on the utility possibility curve CD is reached that lies within the Pareto region of F (dashed lines).

It is important to know that the Kaldor-Hicks criterion only requires that it is possible for the disadvantaged economic subjects to compensate for the loss of benefit by the beneficiaries, not that this actually takes place. An additional value judgment is required to assess the desirability of such a measure.

Problem of reversibility

A short time after the conception of the criterion, Scitovsky showed that it is reversible and therefore inconsistent in certain situations. A change in an economic situation, which according to this criterion increases the welfare of society as a whole, also leads to an increase in prosperity if it is carried out in the opposite direction, i.e. if it is reversed. This problem can arise if the utility possibility curves intersect and the bundle of goods considered after the change in the economic situation is not preferred to the old bundle of goods by both economic agents. This is to be expected above all if the preferences of the observed individuals differ greatly.

- Example (see picture)

- In the initial situation, the utility possibilities curve AB and the distribution situation F are given. After the change in the economic situation, the utility possibilities curve CD and the distribution situation G now apply. In this new situation G, the welfare of X has increased while that of Y has decreased. From G, by redistributing the bundle of goods, situation H can be reached, in which the welfare of Y has remained the same compared to the starting point and that of X has increased. According to the Kaldor-Hicks criterion, social welfare has increased.

- But if one considers G as a new starting situation and the return from G to F, then the same argument can be applied in the opposite direction: From F, point N could be reached through redistribution, at which the welfare of X increased compared to G and that of Y has remained constant. The return from G to F also increases welfare.

- So one arrives in both directions with an increase in social welfare as a whole, a contradiction. Such inconsistencies always occur with intersecting utility possibility curves if the distribution situations relevant before and after the change in the economic situation lie on different sides of the intersection of the corresponding utility possibility curves.

literature

- Hal R. Varian : Intermediate Microeconomics (6th ed. 2003), pp. 15-16

- Helga Luckenbach: Theoretical foundations of economic policy , 2nd edition 2000, Munich, Verlag Franz Vahlen.

Original works :

- John R. Hicks: The foundations of welfare economics . In: Economic Journal . tape 49 , no. 196 , 1939, doi : 10.2307 / 2225023 .

- Nicholas Kaldor: Welfare Propositions of economics and interpersonal comparisons of utility . In: Economic Journal . tape 49 , no. 195 , 1939, doi : 10.2307 / 2224835 .

Web links

- Steve Randy Waldman: Welfare economics . In: Interfluidity . May 30 - July 7, 2014. Retrieved on May 30, 2015. Five-part English article series that deals with the compensation criterion and its limitations, especially in parts 2, 3 and 4.

Individual evidence

- ^ Tibor Scitovsky: A note on welfare propositions in economics . In: Review of Economic Studies . 1941.