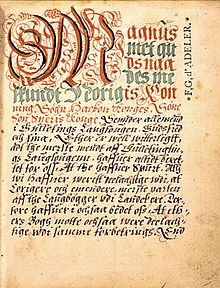

Landslov

The Landslov (German 'Landrecht') of King Magnus Håkonsson lagabøte (1263–1280) represents the greatest legislative achievement of the Scandinavian Middle Ages and was valid in many areas until modern times.

prehistory

After the turmoil of the long Norwegian civil war , a period of inner peace began for Norway. The kingship rose to a power that it had never had before. King Magnus wanted to be equal to the rulers of the west and the continental south not only in power and royal rights, but also in way of life. So he imported the way of life of the royal courts serving as models. He was in regular contact with the English royal court, he married a daughter to the Spanish royal court, his envoys came to North Africa and a friendship connected him with the Hohenstaufen Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire Friedrich II.

The desire to introduce courtly customs of the continent came into play in Hirðskrá's allegiance . An integral part of his efforts to come culturally on par with the continental rulers was the modernization of law. To this end, he sent capable people like Audun Hugleiksson to continental universities and trained them in the sciences that are relevant for the organization of a state. After their return, the legal work began.

Amendment work

Embedding in the existing order

First the Landslov (land law) was renewed. Magnus left it with the four existing laws of the four thing districts. But these four laws now had the same content. The king could not create new law at that time. Every revision of the law had to be presented as the restoration of an earlier, uniform, ideal legal status that only degenerated over time. So formally there were still the law books of Gulathing, Frostathing, Borgarthing and Eidsivathing. It also preserved the peculiarity of developing the right to individual cases and examples, possibly depicting and painting. As far as possible, the old legal antiquities - albeit Christianized - were included in the new law. There are many old legal rites, but also new ones. The admission of an illegitimate son into the family may serve as an example of a Christianized legal age ( Vm ætleiding ; V, 8):

- In this way, a man can improve the condition of his (illegitimate) son by introducing him to the sex if he chooses, provided that he who is closest to the inheritance agrees. If he has sons born in wedlock, everyone who is of age may agree for himself, but none for those who have not yet been born or are still underage, and those who have been introduced into the sex no more heir than those who are entitled to the right of inheritance granted him. He should grant him the right of the Odal who holds the Odal among them. Now the one who introduces the man into the family, and the one who grants the inheritance or the right of Odal, and the one who is to be introduced into the family, should all go to the church door together and all collect a book. Then the one who introduces the man into the sex should say: 'I introduce this man into the sex, to the goods that I give him, to the right to penance and gifts, to the seat and armchair and to all rights that are in the Is attested to by the code of law and whoever is introduced into the family is said to have. ' In the same way women should be introduced to the sex like men. ...

The rite is stripped of the pre-Christian features and relocated to the church door. An example of the formation of a rite that did not exist before is the change of status of a beggar ( Ef maðr gengr með uanar vol ; IV, 28):

- Every man who is of age and goes from house to house and asks for alms has no right to penance as long as he is begging, even if he has been sent away against his will, if he is only healthy and able to work, except himself looks for work and does not get it. But as soon as he buys the food for himself and clothes or weapons, or his relatives procure this for him, then he is immediately in possession of the claim to penance again, even if he does not throw off his staff and satchel on the thing. But the king has no claim to penance from anyone who does not have it for himself.

Throwing away the baton and satchel on the thing as a formal change of status is a new formation.

The requirement also remains that a law only becomes valid when it has been accepted by the thing called for it. At the end of the Landslov, for example, it is documented that the law was presented and accepted at the four thing sites, even if the thing could not refuse at all at that time. The classification of legal material was also retained.

Innovations

What was new, however, was the character of the legal code as a law, i.e. not just a documentation of applicable law, but an imperative that claims to be obedience and compliance. Another new feature was that the same law should apply throughout the country. Thirdly, what was new was that the king claimed the right to legislate for himself and also reserved the right to further training and changes. Fourth, it was a break with tradition that the king made himself chief judge. The jurisdiction previously lay exclusively with the thing assembly.

The old, very far-reaching right of self-help was not eliminated, but severely curtailed. In the introduction to the version prepared for the frostathing it says:

- Most will know the great and varied harm the families of most men in the country have suffered from manslaughter and the loss of the best men, which has become more of a habit here than in most countries.

Endeavoring to improve culture, he points out that it is shameful if this is known in the countries of well-mannered people. Nevertheless, he did not yet dare to abolish the obligation to revenge, but limited himself to condemning the family principle of talion, according to which it was not the manslayer who fell victim to vengeance, but some other man in the hostile family who equaled the slain in dignity and position, even if he did had nothing to do with the manslaughter. But the baseless manslaughter falls into the sharpest form of peacelessness. It was also new that everyone had to arrest a manslayer or other criminal.

In the old law there were extensive explanations about the calculation of the kinship fines that a kinship had to pay if the other kinship was killed. Magnus abolished the kinship penalty. Instead, the penalty was only to be paid by the perpetrator out of his or her property to the heirs of the dead man. He also abolished the man's right to kill on the spot the man he caught red-handed in adultery with his wife or with a close relative. In future the man only had one right to penance.

The fines due to the king were previously one of the king's main sources of income, as they could go as far as the complete confiscation of all of the perpetrator's belongings. They have been significantly reduced, down to 1/4 of the original amount. In general, the king's claim to penance took a back seat to the injured party. As far as the land of the eight decayed had been confiscated, the heirs were able to buy it back within 10 years. Magnus also ordered that the person who fell into eighth of his assets should first be paid the private fines, then the debts. The king got the rest. If there were still children, their maintenance claim should also take precedence. The king's right to grace has been expanded and reorganized many times. The king also received a right of first refusal on all goods.

There have been changes in inheritance law with regard to the succession of previously disregarded persons.

The work involved in weddings and funeral feasts was limited by law to two days as a penalty for guests and hosts. Gambling became a criminal offense. Bets were unpunished, but not legally valid. Police elements of public order already began to appear here.

There were also innovations in procedural law: Up until now, the oath assistants had to swear the oath of the party who was obliged to provide evidence, even though they did not even know the facts. Now the litigant should swear the facts, but the oaths only that they did not know otherwise. For certain legal transactions, the witnesses were no longer sufficient, but written form was required, e.g. B. for marriage contracts, property and farm purchases and for transactions worth over 10 silver marks . With these regulations, however, it is certain that they were not observed among private individuals.

The Church in Law

The changed and more conflictual relationship between state and church is expressed in the fact that in the second section a Christian law was included as before, but the provisions were only general and were limited to the delimitation of the powers between king and bishop. In the previous laws there were very detailed regulations for church life. The Icelandic annals show that on the Frostathing of 1269 the king was only authorized to amend the secular parts of the law. Obviously, Christian law should only be amended in agreement with the archbishop, but this was not possible in the situation at the time. However, the earlier provisions had largely become obsolete due to the concessions made by the king's predecessors.

So that there was not a noticeable loophole under the heading "Christian Law", the regulation of succession to the throne was inserted there. Under the influence of the Church, this was decisively modified in one point compared to earlier. The illegitimate son immediately followed the legitimate son in the law of the previously applicable Håkonarbók. Now he is only in seventh place.

structure

- prolog

- Thing trip. (These are rules about who has to come to the thing and how often, what is negotiated in what manner on the thing, how courts are formed, how a formal summons to the court is made)

- Christian Law. (It is a matter of the right creed, the powers of king and bishop, the prohibition of opposing kings, succession to kings, via the oaths of the king, the jarl, the baron, the law speakers and the free peasants).

- National defense. (It concerns the mobilization [mobilization, suffering], the building of ships, the formal call-up by sending the arrows of war, the shore watch, the military tax, desertion, weapons and equipment and the duty of assistance to pirates).

- The holiness of men. (Contains the entire complex of manslaughter, assault and assault. Also regulations on selling a free man, but also slander and begging).

- Inheritance law. (It deals with marriage law, matrimonial property law, succession, the division of inheritance, the treatment of minors, the wedding ceremony and the funeral ceremony).

- About the Odal law (Odal was originally the general property, later a property protected by special family law. This is about the property traffic and the treasure trove).

- Land lease. (The right of lease, arson, legal fences, animal husbandry, maintenance of the traffic routes, ferry obligations on rivers, fishing, hunting for falcons, hunting rights in general, right of the Almenden).

- Sales law. (Regulations on illegal removal, lawsuits for monetary claims, the king's right of first refusal, forgery when selling, evidence when buying, lien, renting cattle, selling cattle with hidden defects, lending, assumption of debt, women's sales rights, employment contract for farm workers, regulations on sailing out , Prohibition of play, dimensions and measuring vessels).

- Theft (mouth robbery in need, theft, receiving stolen goods, house searches, moving landmarks, oaths and perjury).

- Improvements to the law (This regulates the reduction of fines, the prohibition of revenge on anyone other than the perpetrator, the limitation of the penance to the king for manslaughter, the abolition of the family's liability for the manslaughter and a list of the legislative changes that were already made in the previous Chapters were made).

- The formula for enacting the law through the ting assemblies.

literature

- Land rights of King Magnus Hakonarson . Germanic rights New series. Edited by Rudolf Meissner. Weimar 1941.