Miranda v. Arizona

| Miranda v. Arizona | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||

| Decided June 13, 1966 |

||||||

|

||||||

| statement | ||||||

|

The right against self-incriminations enshrined in the 5th Amendment to the Constitution obliges the criminal prosecution to keep suspects silent about their rights and to clarify their right to a lawyer. |

||||||

| Positions | ||||||

|

||||||

| Applied Law | ||||||

Miranda v. Arizona is a major landmark judgment of the Supreme Court of the United States for the right to remain silent . After that suspects must in criminal matters before the police questioning their right to consult a lawyer and their right to remain silent, be pointed.

background

In 1963 Ernesto Arturo Miranda (1941–1976) was arrested for robbery , kidnapping and rape . He was interrogated by the police and immediately made a confession. During the trial, prosecutors only offered Miranda's confession as evidence. Miranda was found guilty of kidnapping and rape and was sentenced to 20 to 30 years in prison. Miranda's attorney appealed to the Arizona Supreme Court, but it was dismissed. He then appealed to the highest authority, the United States Supreme Court .

The decision

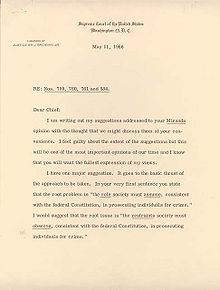

Chairman Earl Warren , a former prosecutor , announced the judgment of the court: Due to the compulsive nature of police interrogation, a confession will not be admitted unless the suspect has been briefed on his rights under the 5th and 6th Amendment to the United States Constitution and he expressly waives this. Accordingly, Miranda's conviction was overturned.

At the same time, the Supreme Court laid down a number of requirements for police interrogation:

“The person in custody must, prior to interrogation, be clearly informed that he has the right to remain silent, and that anything he says will be used against him in court; he must be clearly informed that he has the right to consult with a lawyer and to have the lawyer with him during interrogation, and that, if he is indigent, a lawyer will be appointed to represent him. "

“The person in custody must be clearly informed before interrogation that he has the right to remain silent and that anything he says will be used against him in court; she must be clearly informed that she has the right to consult a lawyer, to be interrogated in his presence and, should she be penniless, to have a lawyer appointed to defend her. "

The court also determined what to do if a suspect wishes to exercise his rights:

“If the individual indicates in any manner, at any time prior to or during questioning, that he wishes to remain silent, the interrogation must cease […] If the individual states that he wants an attorney, the interrogation must cease until an attorney is present. At that time, the individual must have an opportunity to confer with the attorney and to have him present during any subsequent questioning. "

"If the person expresses in any way before or during the interrogation that he or she wishes to remain silent, the interrogation must be broken off [...] If the person declares that he wants a lawyer, the interrogation must be interrupted until until a lawyer is present. At this point the person must be given the opportunity to consult with their lawyer and be interrogated in his presence. "

Although the American Civil Liberties Union asked the court to require that a lawyer be present at all police interrogations, Warren refused to go that far in his judgment.

Warren also referred to the FBI's practice and the Uniform Code of Military Justice guidelines , both of which required a suspect to be instructed about his or her right to remain silent. At the FBI, the notice had to include a reference to the right to a lawyer.

The judges who rejected the verdict spoke out against the disclosure requirements, since they assumed that suspects would always ask for a lawyer and would no longer give confessions. They viewed the verdict as an overreaction to the problem of coercive questioning.

Effects of the judgment

Miranda was tried a second time. The confession could not be used, instead the prosecution relied on testimony and other evidence. Miranda was again sentenced to 20 to 30 years in prison.

After the verdict, police officers were trained nationwide to inform suspects of their rights when arrested. This duty to inform is known today as Miranda Warning (German: Miranda Warning).

The Miranda ruling attracted widespread criticism soon after it was announced, as many believed it was unfair to educate criminals about their rights. Richard Nixon and other political conservatives condemned Miranda for undermining the efficiency of policing and only adding to crime. After taking office as President of the United States , Nixon promised that he would only appoint Supreme Court justices who interpreted the constitution narrowly and held back as judges. The Crime Control and Safe Streets Act, a federal act in 1968, attempted to repeal Miranda for federal crimes. The content of the law was never checked for its constitutionality, because no public prosecutor's office referred to it in criminal proceedings.

Over the years, however , Miranda became widely recognized and accepted. Due to the large number of American police series exported, the Miranda rights became known worldwide.

"Miranda Warning"

The judgment stipulated neither a specific wording nor a specific order. The practice in the states therefore differs slightly from one another. For example, the following text is used:

“You have the right to remain silent. Anything you say can and will be used against you in a court of law. You have the right to have an attorney present during questioning. If you cannot afford an attorney, one will be appointed for you. Do you understand these rights? "

A typical "Miranda warning" is therefore in German translation:

- “ You have the right to remain silent. Anything you say can and will be used against you in court. You have the right to call a defense counsel for any questioning. If you can't afford a defense attorney, you will be provided with one. Do you understand these rights? "

In some states, the following additional questions are asked:

- “ Did you understand the rights I just read to you? "

and

- “ Do you want to speak to me in view of these rights? "

Later developments

Since the original ruling, courts have also ruled that the rights reference must be "relevant". So the suspect is asked if he understands his rights. In addition, courts have stipulated that these rights must be relinquished with full knowledge and understanding and with free will. Since then, many police stations have had forms that suspects can use to give up their Miranda rights with their signature.

A confession made in violation of Miranda’s rights can still be used to challenge contradicting statements made by the suspect. However, this is only the case if the suspect gives up his right to remain silent during the trial and testifies himself.

A "spontaneous" statement by the suspect in custody who has not been advised of his or her rights can also be used as evidence, as long as the statement is not based in response to questions from the police or other police conduct that would have encouraged such a statement.

There is also an exception to protect “public safety” if the Miranda notice is not given, because immediate interrogation is necessary to avert a general danger. In this case, the suspect can be questioned by the police without notice and his answers can be used against him in court.

Miranda also survived his review in the Dickerson v. United States in 2000, when federal law was up to repeal Miranda . The question was whether the Constitution itself prescribed the reference or whether it was a result of judicial interpretation. In the Dickerson case , the judges ruled 7-2 that "the clues have become part of the national culture." In a negative opinion, Judge Antonin Scalia denied that the notice was required by the constitution, stating that a violation of the rules in Miranda was not unconstitutional.

Trivia

The 1973 feature film The Marcus-Nelson Murder Case , which forms the pilot for the crime series Kojak - Operation in Manhattan , deals with the subject. The subject is also dealt with in the action film Red Heat when the American policeman Art Ridzik tries to explain the laws of his country to his Russian counterpart Ivan Danko.

See also

literature

- Saul M. Kassin et al. Why People Waive Their Miranda Rights . In: Law and Human Behavior 28, 2004, pp. 211-221

- Regula Schlauri: The prohibition of self-incriminating in criminal proceedings: Concretization of a basic right through comparative law. Schulthess, Zurich 2003. ISBN 3-7255-4595-2

- Gary L. Stuart: Miranda. The Story of America's Right to Remain Silent. University of Arizona Press, Tucson 2004. ISBN 0-8165-2313-4

Individual evidence

- ↑ See Harris v. New York , 401 US 222 (1971)

- ↑ See Rhode Island v. Innis , 446 US 291 (1980)

- ↑ Cf. New York v. Quarles , 467 US 649 (1984)

- ↑ Red Heat (1988) - Quotes - IMDb. In: imdb.com. Retrieved November 20, 2017 .

Web links

- Full text of the judgment (English)