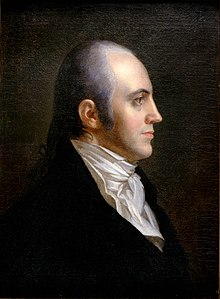

Aaron Burr

Aaron Burr (born February 6, 1756 in Newark , New Jersey ; died September 14, 1836 in Port Richmond , Staten Island , New York ) was an American politician . From 1801 to 1805 he was the third Vice President of the United States under Thomas Jefferson .

Burr rose to be one of the most influential New York politicians in the 1780s and 1790s, serving as the New York Attorney General from 1789 to 1791 . From 1791 to 1797 he represented the state in the United States Senate . He initially belonged to the Democratic Republican Party and was nominated by her in 1796 and 1800 as a vice-presidential candidate at Jefferson's side. In the controversial presidential election in 1800 , which the House of Representatives had to decide, it was assumed that he had intrigued with the federalist opposition to usurp the presidency, and so he soon found himself isolated in his own party. In the 1804 election he was no longer nominated and then joined the gubernatorial election in New York with the support of the federalists , but lost it significantly. For his defeat he blamed a character assassination campaign by his long-time rival Alexander Hamilton and challenged him to a duel . On July 11, 1804, Burr mortally wounded Hamilton. He was then charged as a murderer in two states , but never stood on trial for it. In order to avert the end of his political career or at least his financial ruin, from 1806 to 1807 Burr agreed with General James Wilkinson to equip an expedition in the Mississippi valley, the aim of which was allegedly to attack the Spanish colonies in North America. He was arrested in 1807 and tried by the Jefferson government for high treason on charges of becoming ruler of an independent state in the American West and striving to split the United States, but was eventually acquitted. The extent and aim of the so-called "Burr Conspiracy" are, like many circumstances in Burr's life, controversial among historians to this day.

Life

youth

Burr came from a family of outstanding theologians: his father Aaron Burr was President of the Presbyterian College of New Jersey (now Princeton University ), his mother Esther Edwards a daughter of Jonathan Edwards , the most famous American preacher of his time. John Adams , the second President of the United States, wrote in retrospect in 1815 that never in history had a child been born with such a promising parentage. However, Burr's father died in September 1757, the mother a year later. With his older sister Sally he grew up from 1760 on in the care of his uncle Timothy Edwards, who gave the children a proper upbringing for the family and hired the legal scholar Tapping Reeve as a private tutor.

At the age of only eleven, Burr made his first application for admission to the College of New Jersey, but was rejected because of his age and "studied" the curriculum at home for another two years. When he was finally accepted in 1769, he was classified as a sophomore because of his educational background ; he graduated after three years. During this period, under the presidency of John Witherspoon , the College of New Jersey became America's most politically radical college, and as tensions between the colonies and motherland Britain grew, revolutionary ideas quickly spread among students. Many leading figures of the American Revolution emerged from the Princeton classes of this time, for example James Madison , Gunning Bedford, Jr. , Philip Freneau and Hugh Henry Brackenridge from the graduating class of only 13 graduates of 1771 , and Aaron Ogden from Burr's graduating class of 1772 , Henry Lee and William Bradford . Princeton students trained in rhetoric and reasoning at two competing student clubs, the Whig Society, to which Madison and Freneau belonged, and the Cliosophic Society . In some cases, personal friendships and hostilities developed in these student leagues, which lasted for a long time and were later to have political effects; During these years, Burr, as a member of the Clios, forged a lifelong friendship with William Paterson , the club's founder.

After graduation, Burr initially stayed in Elizabeth and toyed with the idea of becoming a pastor. In view of his ancestors, he seemed destined for this career to many of his contemporaries, but in the end Burr himself had doubts about his faith. In the fall of 1774 he began to study theology with Joseph Bellamy in Bethlehem, Connecticut , but in the spring he changed his mind and began to train as a lawyer with his former tutor and current brother-in-law, Tapping Reeve.

Soldier in the War of Independence

Burr's absence in this painting, one of the iconic images of the American Revolution, is striking given his nationally acclaimed role in the events depicted - Trumbull drew his friend instead of Burr Matthias Ogden entered the scene, who at that time was demonstrably in the hospital.

At the outbreak of the War of Independence in 1775, Burr and his childhood friend Matthias Ogden volunteered for the revolutionary Continental Army . In September he set out as a member of Benedict Arnold's expeditionary force on a march through Maine to the British city of Québec . It was intended to reinforce Richard Montgomery's forces, who had remained victorious in the previous battles of the American invasion of Canada . After the amalgamation of the two armies, Burr was appointed to Montgomery 's adjutant in November on Arnold's recommendation . When Montgomery was killed by a volley of grapes from a British position in the Battle of Quebec on the last day of the year , Burr was in the front row. According to the report of the expedition's chaplain, Burr's college friend Samuel Spring, Burr is said to have attempted at risk of death to recover Montgomery's body; Hugh Henry Brackenridge portrayed the situation in his verse drama The Death of General Montgomery at the Siege of Quebec (1777). News of Montgomery's death and Burr's intervention spread rapidly. The following year, the Continental Congress, after hearings on the circumstances of Montgomery's death, specifically highlighted Burr's courage, which amounted to a military award; However, Burr was not promoted for a long time. It is difficult to say whether Springs and Brackenridge's version is true; the eyewitness accounts are inconsistent.

After the battle, Burr returned south in the spring. In June 1776 he reached New York, the headquarters of Commander-in-Chief George Washington , whose staff was initially assigned to Burr on the recommendation of Joseph Reed . Later biographers have often emphasized that this first meeting of the two men is said to have been marked by mutual aversion. After a few days, Burr was transferred to General Israel Putnam's side as an adjutant . In August 1776 he distinguished himself in the British attack on Manhattan when he prevented the British encirclement of the Gold Selleck Sillimans Brigade by his intervention . The fact that Washington did not think it necessary to mention Burr's deed in the morning orders the following day is said to have been viewed by Burr as a personal degradation. In June 1777 Burr was promoted to lieutenant colonel and initially appointed to the border area of New York and New Jersey. There he took over de facto command of William Malcolm's regiment , which was supposed to protect a pass through the Ramapo Mountains and thus northern New York from the British. Burr's greatest military success in this position, the capture was a British troop without loss in Hackensack during a loyalist invasion of Bergen County in September 1777. Shortly thereafter, he was with his regiment to Pennsylvania ordered where Washington's troops to the British occupied Philadelphia contracted . Here Burr is said to have put down a mutiny among his own troops with his own hands.

He experienced his last fighting in 1778 at the Battle of Monmouth . Like many soldiers in this battle, Burr suffered heat stroke here, the consequences of which would weaken him for years, and was given a leave of absence for a few months. His verdict on Washington's performance in that battle, and the subsequent court-martial against Charles Lee, may have contributed to the further sinking of Washington's respect. In January 1779, Burr was relocated to Westchester County north of Manhattan, where the front line had run since the beginning of the war. In the no man's land between the fronts, Burr did his best to restore public order, including punishing his own militiamen when they plundered. He also set up a spy ring to infiltrate the structures of the loyalists and began to create registers in which information about the civilian population and their political sympathies were collected. When his state of health restricted his work too much, he finally resigned from the army in March 1779. Throughout his life, however, he continued to be dubbed Colonel Burr .

Start of political career

In 1778 Burr met his future wife, Theodosia Prevost, who was ten years his senior. Prevost was still married to a British officer at the time, but had sympathy for the revolution. So after the battle of Monmouth she invited George Washington to her estate, The Hermitage, in New Jersey, where the general then set up his headquarters for a few days. Barely a year after her first husband succumbed to yellow fever in Jamaica , Burr married her on July 2, 1782. The marriage had two daughters, but only one of them reached adulthood. The marriage was burdened by the always fragile health of his wife; She died in 1794 at the age of only 48. In dealing with women, Burr represented very progressive, thoroughly feminist positions for his time and gave his daughter the best possible upbringing; In his study hung a portrait of Mary Wollstonecraft specially made for him .

In the spring of 1782, after barely a year of training, Burr was admitted to the bar and initially practiced in Albany . At the end of the war, he settled in Manhattan in 1783 and opened his own law firm on Wall Street . In 1781, New York State had banned loyal lawyers - who at least in the city of New York were clearly in the majority - from practicing their profession, so that there were now many opportunities for inexperienced lawyers such as Burr or his later arch-rival Alexander Hamilton to make a name for themselves . Like Hamilton, Burr was soon one of the most outstanding and best-paid lawyers in town; hardly any of the major lawsuits of the next 20 years went without the involvement of at least one of the two. Burr and Hamilton were sometimes opponents in the courtroom, sometimes they found each other united on the side of the prosecution or defense, for example in 1800 in the sensational murder case People v. Levi Weeks.

His political career began in 1784 when he was elected one of the nine New York City MPs in the State Assembly . After initial passivity, he only worked in some committees of this parliamentary chamber after his re-election in 1785. In his second year he brought among other things a bill for the immediate abolition of slavery in New York, but it failed. In his private life, Burr - like Hamilton, who was also publicly known as an opponent of slavery - continued to keep some household slaves. In view of his later positions, it is astonishing that Burr apparently did not participate in the debate about the ratification of the federal constitution , in which the proponents of a strong central government (the so-called federalists around Hamilton) and the advocates of the sovereignty of the individual states (the anti- Federalists ). Although he had been proposed as a delegate to the ratifying assembly of New York State in the summer of 1788, he had rejected the request. Hamilton's assumption is probably correct that Burr was originally opposed to the constitution, especially since he was already moving in anti-federalist circles at that time. If the nation was already divided by the dispute over the constitution, the political landscape of New York was even more rugged due to family entanglements and regional differences. As Burr's biographer James Parton wrote in an often-quoted bon mot , New York was at the time " like Gaul divided into three parts ”- the domains of the extensive Clinton, Livingston and Schuyler families and their political friends. Governor of New York State had been the anti-federalist George Clinton since 1777, who was hated in the city of New York, which was dominated by federalist-minded merchants, as well as by rural landowners like the Livingstons and Schuylers. In 1789, Burr joined a concerted Hamilton campaign by the city's federalists to oppose Clinton with Robert Yates . Clinton narrowly won the election. Probably to win Burr for his camp, Clinton appointed him after his election as Attorney General of New York State, a position roughly equivalent to the rank of Attorney General .

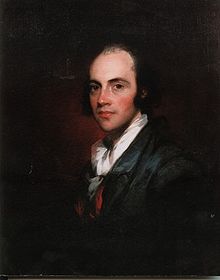

Senator for New York, 1791 to 1797

Collection of the New Jersey Historical Society, Newark.

In 1791 Burr first got into a political conflict with Alexander Hamilton , now finance minister in President Washington's cabinet and the defining figure of the federalists at the federal level as in New York. Governor Clinton nominated Burr for New York's new Senatorial position in Congress this year to get rid of the federalist electorate, Hamilton's father-in-law Philip Schuyler . To this end, he allied himself with Robert R. Livingston , Chancellor of New York State, who had previously belonged to the Hamilton camp. Livingston broke with the Federalists out of bitterness that his clan had come out empty-handed in the election of New York's two Senators for Congress in 1789, after Hamilton intrigued against "his" candidate James Duane (married to Maria Livingston, a third cousin) and instead had taken the second senatorial post to Rufus King . Clinton and Livingston were united by a desire to humiliate Hamilton, and so they used their influence to finally secure the majorities in the upper and lower houses for Burr's election. In March 1791 Burr took up his mandate in the Senate, his successor as Attorney General was Livingston's son-in-law Morgan Lewis .

Shortly after his election, Burr had a conspiratorial meeting with Robert R. Livingston and Virginia State's two leading anti-federalists , James Madison and Thomas Jefferson . What the four statesmen, who officially met to collect plants for their herbaria in the forest, agreed to, but the "botanizing tour" of the two southerners is considered by many historians as an important milestone in the emergence of the Democratic-Republican Party , as they are the anti-Hamiltonians Virginia united with those of New York, creating a prerequisite for a national political party in the modern sense. When the First Party System consolidated in the years that followed, Burr, despite his obvious closeness to the Republicans, did not want to see himself as a party member. In many respects, however, he was a promising ally for the Republicans, who had previously only dominated in the southern states: he was popular in the politically divided New York, and in federally dominated New England he was respected in many places because of his ancestry. That his grandfather and father were senior Presbyterians made him attractive to this constituency nationwide.

In elections, Burr was always supported by a group of loyal followers who, in historiography, are often understood as a separate political force that maneuvered between the two established parties. The former Clintonians Marinus Willett and Melancton Smith as well as the federalist Peter Van Gaasbeck were among the "Burrites" of the first hour ; later joined by Matthew L. Davis , the three brothers John , Robert and Samuel Swartwout and the doctor Peter Irving . Burr's reputation as a referee may have been a reason why he was brought up as a candidate in the New York gubernatorial election of 1792 by electors from the federal camp, but Hamilton managed to prevent this, so that finally John Jay faced Clinton. The outcome of the extremely narrow election was decided in court - in the political and legal debate that followed, Burr sided with those who declared Clinton's victory to be legitimate despite many irregularities. In 1792, Burr first came into play as the Republican candidate for the US vice presidency (the re-election of Washington as president was not doubted by either side), but the main Republican strategists, James Monroe and James Madison, spoke out against Burr's candidacy and sent George Clinton into the race instead. In the election towards the end of the year, John Adams finally asserted himself in front of Clinton - Burr received the vote of an elector from South Carolina despite his candidacy . In this first of three presidential elections in which Burr was supposed to run, Hamilton intrigued at least in his correspondence against Burr. In a letter to an unknown addressee, he stated that he saw it as his "religious duty" to prevent Burr's career.

In the Senate, Burr soon rose to one of the opinion leaders of the Republicans, also because the party lost its most prominent elected officials with the retirement of Jefferson from his offices in 1793 and the appointment of James Monroe as ambassador in Paris in 1794. In 1793/94 he was one of the most ardent defenders of Albert Gallatin , whom the federal Senate majority removed from his mandate because he had allegedly not been an American citizen long enough to be eligible for election. In 1794 he was among the minority of ten senators who voted against ratifying the Jay Treaty with Great Britain; Even the appointment of Jay as Washington's negotiator was unconstitutional. Like Madison and Jefferson, Burr advocated an alliance with France instead of an agreement with Britain . For example, on the occasion of France's military successes in the European coalition wars , he drafted an official congratulation from the United States to the French Republic, but the advance failed again because of the federal majority in the Senate. When, after the arrival of the new French ambassador Edmond-Charles Genêt in New York and elsewhere, democratic clubs based on the Paris model emerged, Burr defended their rights to free speech against censorship efforts by the federalists. During these years, there were increasing signs that Washington was not well-disposed towards Burr: When Burr began researching the archives of the State Department in the winter of 1792 for his - ultimately never written - history of the War of Independence, Washington issued a personal order to remove Burr Deny access to the archives. When France rejected Governor Morris as American ambassador in 1794 , Monroe and Madison proposed President Burr as his successor, but Washington rejected the request on the grounds that he would not appoint anyone to high office in whose "personal integrity" he did not trust have. It can be assumed that Hamilton, as Washington's closest confidante, was not uninvolved in these episodes.

By the presidential election in 1796 , Burr had sharpened his profile in the Republican Party to such an extent that he believed he had a good chance as a vice-presidential candidate at Thomas Jefferson's side, especially since Clinton was politically weakened. In addition to the "Burrites", it was above all John James Beckley , the leader of the Republicans in Pennsylvania, who initially supported Burr. Burr went to Monticello himself in October 1795 to talk to Jefferson, and in the spring and summer of the election year traveled through New England and New York to collect federal electors. His forays into the opposing camp led Beckley to conclude that Burr was less interested in the party's success than his own. Concerned that Burr might get more electoral votes than Jefferson, he recommended to Madison that the Virginia Republican electorate squander the second of their two votes on unlikely candidates. The president and vice-president were elected in one ballot until 1800, with each of the electors having two votes to cast; The man with the most votes became president, and the man with the second most votes became vice-president. In fact, in the December 20 election of Virginia Jefferson electors, only one voted Burr. In total, Burr only got 30 votes. Given the 68 Jefferson votes, the lack of party discipline was evident. In the federalist camp, however , something similar happened: Jefferson received more votes overall than John Adams' vice- elect Thomas Pinckney , so that for the first and only time in American history, the president and the vice-president would belong to different parties.

Member of the New York House of Commons, 1798-1800

In 1803, Burr had to lease Richmond Hill due to lack of money to Johann Jakob Astor , who immediately divided the area into parcels and built tenements on it.

Burr's six-year tenure as senator ended in 1797. By that time, the federalists had won a majority in both houses of the New York legislature and re-elected Philip Schuyler to the senatorial post. Apparently unaffected by the associated loss of prestige, Burr immediately ran for election to the New York House of Representatives, and was elected for one year each in 1798 and 1799. During these two years he always tried to warm some of the federal MPs to Republican concerns, and even persuaded some of them, such as Jedediah Peck , to change camps. If he had failed 15 years earlier with a bill for the immediate abolition of slavery, he has now at least passed a law for the gradual abolition. He failed, however, with the bill, according to which the electors of New York in the presidential election should be determined by direct elections and no longer by the legislature; He also tried to reform New York's land sale and bankruptcy law and, for example, advocated the abolition of guilty detention - quite selfishly, because he himself was always threatened with financial ruin over the years, which, however, did not prevent him from being active flourishing speculation with land patents on the as yet undeveloped west of New York. So it was also in his own business interest that as a politician he tried to push through infrastructure projects and tax breaks for this part of the country.

Burr's most amazing achievement at the time was the establishment of a bank. In New York, the only two public banks, the Bank of New York and the branch of the Bank of the United States , were firmly in federal hands and often denied Republicans loans, so that political friends were favored. In order to break this monopoly, Burr resorted to a ruse and put before Congress a proposal to establish a private corporation with public participation and a monopoly on the water supply of the city of New York in order to improve the disastrous sanitary conditions by building new fresh water pipes . He introduced the draft law in March 1799 shortly before a break of several weeks as a matter of urgency and added to it a clause that was only one sentence long, which allowed the company called the " Manhattan Company " to use its excess capital in "monetary and other business, so they are not inconsistent with the constitution or laws of the United States. Since apparently neither the few delegates who had traveled, nor the senators nor Governor John Jay were able to grasp the scope of this provision, the proposal became law. The waterworks bank opened in September of that year, and the federal banking monopoly was broken. This advance, too, was not entirely unselfish on the part of Burr; towards the end of 1802 he was already in the red with the bank with 65,000 dollars. Chase Manhattan Bank , one of the largest credit institutions in the world, evolved from the Manhattan Company's bank ; the New Yorkers, however, had to wait 40 years for a proper water supply.

Burr's efforts to organize Republicans in New York became more and more national as the 1800 presidential election drew near. Long before the election, it was certain that New York would be the swing state in which the election would be decided. The election of the New York House of Representatives, which would work with the Senate to select electors for the presidential election, was of paramount importance to Republican strategists. Within the state, in turn, the city of New York, which had 13 seats in the House of Commons, played a key role in the struggle for the majority, as the respective majorities in the rural electoral districts appeared to be consolidated. In the spring of 1800, Burr managed to organize a highly efficient election campaign within a short period of time. He persuaded some of the city's most prominent citizens to run for the party - his list of nominations included former post minister Samuel Osgood , General Horatio Gates , who was revered as a war hero , and a representative from each of the two dominant political clans: Brockholst Livingston and the former Governor George Clinton personally. For weeks, Burr's Richmond Hill estate resembled a field camp where Party soldiers received their orders; Burr had a dossier drawn up on the presumed political position and the likelihood of changing it for every single person eligible to vote in the city. He sent German-speaking election workers to the electoral districts that were mostly inhabited by German immigrants. On May 1st, election day, a large number of Republican litter-bearers and coachmen appeared out of nowhere, bringing old and frail voters to the polls. After the vote count, it was clear that Burr's candidates had won all 13 seats - Burr himself was also re-elected to the House of Commons, this time as MP for Orange County .

Vice President, 1801-1805

The 1800 presidential election

After the election success in New York, it seemed to Republican strategists inevitable that the vice-presidential candidate alongside Jefferson would have to come from that state as well. In addition to Burr, Clinton and Robert R. Livingston came into question. Reports of how the decision in Burr's favor were diverged, but it appears that Albert Gallatin , who had been so loyal to Burr in the 1794 Senate, influenced the decision. The party officially confirmed the nomination at a national caucus in Philadelphia. It was also decided to require the Republican electorate to pledge to give both of their votes to their own candidates in order not to repeat the strategic mistake made by both parties in 1796. When the results of the December 1800 election became known, it turned out that the Republican candidates had won the election. However, since all electors had actually adhered to the guidelines, there was a stalemate of 73 to 73 votes between the winners Burr and Jefferson. In this case the constitution provided for an election in the House of Representatives in which each state had one vote; Jefferson needed a simple majority of states to vote. Of the 16 state delegations, however, only eight were in Republican hands.

In this situation, many federalists sensed the possibility of preventing Jefferson's presidency by voting for Burr. It wasn't just about postponing a decision: Quite a few federalists believed they could get Burr to switch sides with the prospect of the highest office in the state. The messy situation gave rise to rumors and intrigues on all sides and also divided the parties. Burr's behavior during this period is still debated today. Although there are no surviving statements from Burr in which he opened himself up to the advances of the federalists, after some time he no longer expressed any denials, which some historians interpret as eloquent silence and signs that Burr would not have closed himself off to such a castling. In the vote in February, it actually came to the expected draw. It had to be repeated 35 times until, after six days , Vermont and Maryland abandoned their blockade and abstained. In this election, too, Hamilton agitated against Burr. He once said, "If there is one person I should hate, it's Jefferson" - but when the federalists considered making Burr president, Burr seemed to him to be an even bigger evil. "For God's sake may the Federal Party never be responsible for this man's rise," he wrote to William Sedgwick in January 1801.

As a result of the turbulent election in 1804, the procedure for the presidential election was changed by the 12th Amendment to the Constitution . Since then, the election of the President and Vice-President has been carried out in two formally separate votes.

Burr in office

Jefferson and Burr were so on June 4, 1801 inaugurated . Jefferson had apparently lost all confidence in his runner-up because of the rumors surrounding Burr during the election. Looking back, he wrote in a letter in 1807: “I never took him [Burr] for an honest or outspoken man, rather a crooked shotgun that you could never be sure of where it was aiming or shooting. But as long as the nation trusted him, I saw it as my duty to respect him as well, and to treat him so; as if he deserved it “Already in the first weeks of the new government, the rift in personnel decisions became clear. The new administration had to fill not only its cabinet posts, but also hundreds of other offices across the country. In accordance with the practice of the “ spoils system ,” the American version of patronage, these positions were filled with people who were loyal to the party at the suggestion of deserving party soldiers. Burr submitted a comparatively modest list of five "burrites" for office in New York. Only two of the nominees were actually appointed by Jefferson, but the President did not respond to the other candidates even after various inquiries. Particularly striking to observers was the omission of Burr's closest confidante, Matthew L. Davis ; Jefferson's inaction in this area led Albert Gallatin , now Treasury Secretary, to ask Jefferson outright in a letter whether the party intends to continue to support Burr. Jefferson did not reply to the letter. The intrigue against Burr hardly started from Jefferson himself, but had its origin in New York. Under the leadership of George Clinton's son-in-law DeWitt Clinton , the previously warring clans of the Clintons and Livingstons had reunited, as they feared for their influence in New York in the face of Burr's political rise. It was the coalition that made Burr senator in 1791 that orchestrated his disempowerment.

The internal power struggles of the Republicans in New York escalated from 1802 to 1804 in the so-called “Pamphlet War.” The occasion was the planned printing of a political pamphlet by journalist John Wood, which criticized the past federalist administration of John Adams in such shrill tones that Burr closed concluded that publication would do more harm than good to the Republican cause. Burr offered to buy up the entire print run in order to compensate the printer and to keep the political peace at the same time. James Cheetham , the editor of the Clinton-controlled New York daily American Citizen , took this offer as an opportunity to accuse Burr not only of censorship, but of conspiracy with the federalists. Over the next two years, Cheetham Burr regularly attacked Burr in the pages of his newspaper with increasingly violent accusations, and the federal press willingly took up the subject. The historian Henry Adams summarizes the situation in often dramatic terms:

“Never before or since has there been such a powerful alliance of rival politicians in United States history, banding together to defeat a single man, like the one now standing against Burr. Because when the enemy circle closed around him, not only could he see Jefferson, Madison, and the whole Virginia Legion there, with Duane and his Aurora at their back; not just DeWitt Clinton with his entire clan and Cheethan and his Watchtower by their side; but also the strangest of all companions: Alexander Hamilton shaking hands with his bitterest enemies to close the ring. "

Burr was reluctant to face this character assassination campaign. In the autumn of 1802 he arranged for the establishment of his own daily newspaper under the leadership of Peter Irving in order to be able to counter the hostile press. The Morning Chronicle appeared numerous anonymous contributions from Burr's confidants and possibly from his own pen over the next two years. A pamphlet in defense of Burr, entitled An Examination of the Various Charges Exhibited against Aaron Burr and a Development of the Characters and Views of his Political Opponents , was written under the pseudonym Aristides by William P. Van Ness . This polemic was of such sharpness and literary quality that it became the best-selling political writing in America since Paines Common Sense . While it provided Burr with valuable service in the meantime, its effectiveness in the long term was limited: long after the "pamphlet war" had subsided in 1804 and Burr's death in 1836, numerous historians were to take Cheetham's accusations at face value.

Indeed, there were some circumstances in Burr's tenure that left federalists and republicans alike puzzled as to his sentiments. One of the first steps taken by the Jefferson administration was to reverse Adams' judicial reform, enacted a few days before the end of his term, with which the outgoing president had created a large number of new judicial posts for life, all of which he had filled with federalists, the so-called " Midnight Judge ". When the vote to revoke the reform ended in stalemate, Burr had the casting vote as Senate President. He initially rejected the draft law for resubmission, which was understood as a warning to his party. When it became increasingly clear that he was being ousted by his own party, he finally resorted to a demonstrative provocation: on February 22, 1802, the birthday of George Washington, who had died three years earlier, to the surprise of those present, he appeared on one of the federalists of the Capital-oriented banquet and made an ambiguous toast to the "union of all honest men" - Henry Adams said a good hundred years later that Burr hurled such a "dramatic insult in the face of the president." When the next presidential election was approaching in 1804, Burr was broken with his party so clearly that it seemed a matter of course that he would not be run as a runner-up again; the Republicans chose George Clinton again. In order to avert the end of his political career, Burr stood thereupon with the support of the federal opposition as a candidate for the New York gubernatorial election in 1804. Only at the price of being able to ally themselves with the actually Republican-minded burrites did many federalists believe that they could again gain a majority in New York. Henry Adams, however, sensed a much more explosive plan behind this new coalition. According to this, Burr got involved with some New England “ultra-federalists” around Timothy Pickering , the so-called “ Essex Junto ”, whose goal was the secession of New England from the Union, and who with Burr also believed they could move New York to join the new state. Later historians have not only relativized the extent of this conspiracy , but also denied Burr's involvement.

Duel with Hamilton

In the April election that year, Burr was clearly defeated by Republican candidate Morgan Lewis . It was not without good reason that Burr suspected another Hamilton intrigue behind his defeat. The latter had already opposed Burr's candidacy in the federalists' first caucus . After he was outvoted, he devoted a great deal of energy to writing letters to federal opinion leaders warning against Burr in increasingly harsh words. Some disrespectful remarks about Burr, allegedly made by Hamilton at a dinner in Albany, found their way into the press. Burr was so hurt in his honor that he challenged Hamilton to a duel . This form of settlement of honor disputes was still widely accepted socially in the United States - both Burr and Hamilton had fought duels before. In New York, however, dueling was forbidden, so duelists usually met on the other bank of the Hudson in the Weehawken Forest in New Jersey . It was here that Hamilton's eldest son Philip was killed in a duel in 1801 .

During the duel on the morning of July 11, 1804, Burr fatally wounded Hamilton with a shot in the abdomen. The exact process is still the subject of much speculation. In the days leading up to the duel, Hamilton not only drew up his will, but also made a few personal remarks about his decision not to aim at the opponent with at least the first of his duel balls, but to waste the first shot - to appease Burr, however also, because a duel is fundamentally contrary to his religious convictions. As a result, Hamilton would have willingly accepted or brought about his own death. Burr, who could not have known about Hamilton's decision, and his second William P. Van Ness later stated that the duelists had shot around the same time and that Hamilton had aimed at Burr, even if the bullet missed its target by far. However, Hamilton's second Nathaniel Pendleton stated that Hamilton's shot accidentally went off prematurely. An examination of the dueling pistols by experts at the Smithsonian in 1976 suggests that the gun trigger - which Hamilton was allowed to choose as the challenger - was prepared. While Burr's pistol had a conventional trigger that required a trigger weight of more than five kilograms, Hamilton's weapon was set to a much lower resistance, which would have given Hamilton an unfair advantage; this manipulation could also explain why, as Pendleton stated, his shot was actually fired too early.

Hamilton's death was received with dismay in New York and his funeral procession was attended by thousands. Even the city's Democratic-Republican Council ordered a day of mourning. Some of these expressions of condolence may also have been politically motivated; DeWitt Clinton, for example, only discovered his appreciation for Hamilton after the duel and saw his death as an opportunity to completely rid himself of Burrs as a political rival. When Burr heard that a murder charge was likely, he fled New York eleven days after the duel, first to Philadelphia, then to the island of St. Simons off the coast of Georgia . In the Republican-dominated south, mourning for Hamilton was significantly lower; the practice of dueling was hardly as frowned upon here as it was in some parts of the north, so that Burr could continue to enjoy the recognition as a gentleman here. So after a few weeks he finally gave up the false name under which he had traveled until then and set out for the capital - in many cities he was received by cheering crowds. On November 5, he appeared in Washington and, to the dismay of the federal MPs, resumed his seat as chairman of the Senate. In New Jersey, meanwhile, an arrest warrant for murder had indeed been issued against him, but over the years the trial has been quiet and silent.

Burr's last few months as Vice President have been very positive for him due to new political developments. The Jefferson administration has now launched the first impeachment proceedings against the federal “midnight judges ”, in particular against Samuel Chase , one of the new Supreme Court justices. Since Burr would chair the hearings as President of the Senate and thus had a key position in the decision, his party vied for his goodwill again. Three of his confidants - his stepson Bartow Prevost, his brother-in-law Joseph Browne, and James Wilkinson - were quickly appointed to government posts in the Louisiana Territory at Burr's suggestion . Burr conducted the Chase hearings with a fairness that was recognized by all sides. On March 2, 1805, the day after the Senate voted to dismiss the charges against Chase, Burr delivered a farewell speech as Vice President that moved many members of the Senate to tears.

The "Burr Conspiracy"

In 1805 Burr's political career seemed to be over, and he was (again) threatened with financial ruin. In the next two years he put his energies into a project that has gone down in history as the "Burr Conspiracy" . The aim and extent of this alleged conspiracy are still controversial today. Apparently, Burr initially hoped to lead a force into Spanish Mexico and "revolutionize" the Spanish colonies in North and Central America, that is, to move them to break away from the mother country. In the fall of 1807 he began building a fleet of river boats to take him and a number of followers down the Mississippi . Burr always stated that his only intention was to peacefully settle lands on the Ouachita River , the so-called Bastrop lands , which he had leased a year earlier. However, contemporaries such as later historians suspected that Burr warlike intentions pursued and become a Napoleon wanted to soar same ruler of a newly created empire in Central America, which he alleged the western areas of the United States as the Louisiana Territory and states such as Tennessee and Kentucky incorporate wanted - it was this charge that led to charges of treason in 1807.

chronology

Burr's plan to wrest Mexico from the Spanish crown dated at least 1796 when he declared himself to be so to John Jay . Hamilton had also planned the conquest of Florida and the Louisiana Territory and then Mexico at the time of the quasi-war in 1798 and even set up an army for it, which earned him the nicknames Bonaparte and Little Mars . However, Burr's plans only became concrete after the United States expanded west through the purchase of Louisiana Territory in 1803. Since then, a dispute has simmered over the unresolved border between Louisiana and New Spain , and war with Spain seemed inevitable. In the coming conflict, Burr evidently hoped, with or without the support of the American government, to distinguish himself as a general or at least to enrich himself as a privateer . In 1804 he discussed these plans with James Wilkinson , commander in chief of the American army since 1800 , who was also appointed governor of the northern Louisiana Territory on Burr's recommendation in 1805. Wilkinson was supposed to be Burr's vice-commander in the planned campaign and was subsequently the central figure alongside him in the developing conspiracy. Some witnesses even later claimed that Wilkinson was their real head. Little did Burr know, however, that Wilkinson had been in the service of the Spanish Crown as a spy since 1787 and regularly briefed the Foreign Ministry in Madrid and the officials in the Spanish colonies. At least to fund the project, Burr first tried to win Britain, which was then heading for war with Spain (the third coalition war ), to the invasion plan. In March 1805 he contacted Anthony Merry , the British envoy in Washington. At first glance, Merry's dispatches to London, which were later found in British archives, weigh heavily on Burr: According to Merry in a letter dated March 29, 1805, Burr asked him for financial and military support for a planned revolt of the Louisiana Creoles , which also included a campaign against Mexico, the secession of the western territories of the USA and the creation of an independent state. The efforts remained fruitless and at most had the consequence that the Spanish ambassador Marqués de Casa Yrujo , who did not go unnoticed these conversations, now believed Burr to be a British spy.

In April 1804, Burr set off on a trip to the American West, ostensibly to survey the progress of a sewer construction company in Ohio in which he had acquired shares. However, at many receptions held in his honor, he was frank about his plans to invade Mexico. The press covered it extensively, and Jefferson was kept abreast of Burr's activities by correspondents. Burr traveled to the Ohio Valley via Pittsburgh, where he met the emigrated Irish nobleman Harman Blennerhassett , who had built a stately home in the wilderness of a river island in the Ohio River . Blennerhassett had Burr hired him for the project, and Blennerhassett Island was to be the starting point of the expedition. Burr found other donors and supporters on his further journey downriver to New Orleans , including the future President Andrew Jackson . During Burr's tour of the West, the federal daily Gazette of the United States published an anonymous letter, which was reprinted nationwide, accusing Burr of promoting the secession of the western states and Louisiana. The author may have been the Marqués de Casa Yrujo himself, who wanted to portray Burr as a traitor to his own country in order to thwart the planned invasion. In light of this, the turn the "conspiracy" took after Burr's return to Washington in the fall of 1805 seems astonishing. Burr decided on a daring bluff and got in touch with Yrujo through a confidante, Senator Jonathan Dayton . In return for a cash payment, he would reveal his real plans to Yrujo. Yrujo accepted the offer and elicited Burr against payment of $ 2,500 and the promise of further money that he was planning not an attack on New Spain , but the forcible storming of the capital Washington and the looting of its banks and arsenals in order to deal with the loot after retreating west to finance the establishment of an independent state in Louisiana. But since Wilkinson had meanwhile informed the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Madrid that Burr had by no means given up on his plans to attack Spain, on the instructions of the Spanish Prime Minister Pedro Ceballos Guerra , Burr received no further payments from the Spanish coffers after the first.

Burr drove the expedition forward in the summer and fall of 1806. On and around Blennerhassett Island he had a fleet of river boats built to carry his followers down the Ohio and Mississippi to New Orleans. All over the country he and his middlemen tried to recruit young men for his project, always leaving them in the dark about the specific goals of the venture. Countless rumors circulated in the West and soon found their way to Washington. Hamilton Daveiss , the federal Attorney General of Kentucky, Jefferson taught in several dispatches about Burr's intrigues and it gave him plans for a coup and treason before, but the president did not respond for weeks. In October and again in November 1806, Daveiss brought Burr to court in Frankfort , the capital of Kentucky, but neither of the two grand juries convened for the trials could find illegal behavior, so that Burr, defended by Henry Clay , after several weeks of negotiations as a free one Mann left the courtroom and made his way to join his expedition fleet. The latter had left Blennerhassett Island in a hurry on the night of December 10-11 and headed downstream - shortly before, according to alarmist reports , Ohio's Governor Edward Tiffin had informed the Congress of his state that Burr had up to 4,000 men under arms and had to stop will; the state militia have been ordered to search Blennerhassett Island.

Meanwhile, Wilkinson had also turned against Burr. In October 1806, Spanish troops had made an advance into American-claimed territory near Natchitoches , which would almost have become a casus belli had it not been for Wilkinson himself having negotiated a provisional agreement with the Spanish commander on the course of the border, the so-called Neutral Ground Treaty . Now that the war had been averted, on the outbreak of which the success of the Burrs and Wilkinson's conspiracy depended, if it was then aimed at an attack on Spain, Wilkinson sought to steer the new situation in his favor. In a letter he alerted Jefferson of an alleged impending invasion of New Orleans by Burr's fleet. He went to New Orleans, had the defenses there reinforced, gunboats hit the Mississippi, and offered a reward for the capture of Burr. His attempt to proclaim martial law, which would have secured him, as the commander in chief of the armed forces, complete control over the judiciary, failed only because of the concerns of William C. C. Claiborne . Uncertainty about the situation heightened when Jefferson received Wilkinson's letter on November 27, warning all officials in the Western states of the conspiracy and calling for increased vigilance. Jefferson rashly stated to Congress that Burr was undoubtedly guilty of the conspiracy.

While Wilkinson presented himself to Jefferson as the savior of New Orleans from a Burr attack, he also tried to put himself in a favorable light to the Spaniards: he charged the Viceroy of Mexico City the sum of 121,000 dollars for services rendered because he had averted a costly war and secured the Spanish possessions from an attack by Burrs. While Burr was slowly advancing downstream with his fleet of four boats and barely 100 men, panic spread in many places. Citizens barricaded their homes along the course of the river, and the Kentucky militia were on standby. In January 1807, Burr went ashore near what is now Natchez to face another lawsuit in Washington , the capital of the Mississippi Territory . The convened grand jury was again unable to find any wrongdoing by Burr, but the presiding judge nevertheless ordered Burr to be taken into custody. In order not to fall into Wilkinson's hands, Burr decided to flee. On February 18, however, he was arrested at Fort Stoddert in what is now Alabama and eventually taken to Richmond, Virginia , where the Jefferson government had brought a lawsuit against him.

The treason trial 1807

Burr was accused of “serious misconduct” (high misdemeanor) on the one hand because of his allegedly planned attack on the Spanish colonies, of filibustering and thus a violation of the Neutrality Act of 1794 , and on the other hand of high treason (according to the constitution, treason ) accused of wanting to attack at least the American city of New Orleans, if not planning a secessionist uprising in the American West - he faces a long prison sentence for the former and the death penalty for treason. The decision to take the case to the Virginia Federal District Court was based on the narrow definition of treason in the American legal system. Treason is defined as the only crime in the Federal Constitution :

“Only warfare against it or the support of its enemies through aid and favor is deemed to be treason against the United States. Nobody may be found guilty of treason, except on the basis of the testimony of two witnesses about the same overt act or on the basis of a confession in a public court session. "

The prosecution faced the problem of where Burr was supposed to have committed such an "overt act" - in the course of his antics in the West, three different juries had failed to prove him wrong. The most promising appeared to the prosecution to incriminate as an "overt act" the hasty escape of Burr's fleet from Blennerhassett Island on December 10, 1806. Since the island was part of Virginia, the case was transferred to the Richmond District Court. At that time, however, the judges of the Supreme Court acted as presiding judges of the district courts on a rotating basis. In the United States v Burr case , this created the juicy situation that John Marshall would preside over the court. Marshall, the United States Chief Justice who had sworn in as Vice President six years earlier, had long been closely and mutually hateful to Jefferson. Jefferson himself was the driving force behind the prosecution, although he did not appear in court. During the four-month trial, he wrote letters to Federal Government Prosecutor, District Attorney George Hay, almost daily with detailed instructions on how to proceed.

Negotiations began on May 22, 1807. So many onlookers gathered in Richmond that the city's population doubled to 10,000, and entire tent cities sprang up on the outskirts. In many ways, the scale of the trial was unprecedented: the government spent more than $ 100,000 on the indictment, found more than 140 witnesses from Maine to Louisiana and brought them to Richmond. Burr was defended by six notable lawyers, including Charles Lee and Luther Martin ; not one of them asked for a reward for his services. The course of the trial also set some precedents in American legal history: for example, the defense demanded that Jefferson be assigned a subpoena in order to obtain relevant government documents that could allegedly exonerate Burr. John Marshall accepted the move after a heated controversy over whether to summon the President of the United States himself . Jefferson's reaction to this has been assessed differently by legal historians: Although he instructed the archives to be searched for the documents, he only communicated this to his prosecutor Hay, but not to Marshall, which can also be seen as a willful disregard of the court.

The central piece of evidence in the process was an encrypted letter (the so-called cipher letter ), which Burr is said to have written to Wilkinson in 1806 and which actually speaks of an uprising in the western territories of the United States. When Wilkinson was heard as a witness, however, he had to admit to the jury that he had manipulated the wording of the submitted letter himself in order to cover up his own involvement in the alleged conspiracy. Who actually wrote the cipher letter is still the subject of historical debate today; In his 1982 biography of Burr, Milton Lomask suspects Burr's co-conspirator, Jonathan Dayton, to be the author. When this evidence was found to be inconclusive, the prosecution focused on providing evidence on the night of December 10th for the "overt act" that made up the betrayal, but the argument was that Burr was not at all at the time was present on the island himself. Hay finally insisted that raising troops for treason would constitute treason, even if the betrayal was not carried out, but Marshall did not allow the mere presumed treasonous intent to be considered an "overt act." On September 1, long before all the witnesses were heard, he called the jury to meet. The jury announced on the charge of conspiracy was "not proven" (not proved) , Marshall quoted the ruling as "not guilty" (not guilty) .

What was Burr actually up to?

The question of what Burr actually wanted to achieve with his small fleet puzzles historians to this day, especially since Burr told so many different people so many different and contradicting things about his goals. Any guess at his real intentions must be speculation. Henry Adams was the first historian to sift through the files on Burr in the European archives and took much of what Burr let the English and Spanish ambassadors know, such as the allegedly planned attack on the capital Washington, at face value; Later historians, on the other hand, have pointed out on various occasions that Burr wanted, for example, from Anthony Merry to use tactical lies to acquire financial support for his project. Even in the 20th century, some historians of the "Burr Conspiracy" came to the conclusion that Burr was guilty as charged, such as Thomas Abernathy (1954) and Francis F. Beirne (1959). Even Sean Wilentz (2005) agrees Burr was the Western states want to drive to secession, and estimates the conspiracy, even if they seem at first glance like a "complicated farce with a huge dance very unlikely characters," as a real danger for American democracy, especially because it revealed the uncertain loyalty of its military (like Wilkinson).

Nancy Isenberg confirmed in its Burr-Biography (2007) theorized that Burr's expedition rather than profitable privateering was planned - the war against Spain would actually broken out, he would attack perfectly lawful Spanish possessions and allowed to plunder; in the case of peace, that would have meant piracy. More or less legal forms of piracy were ubiquitous in the region at that time; With the outbreak of the Napoleonic Wars and later the Latin American independence movements, countless captains hunted ships of hostile nations in the Caribbean and the Gulf of Mexico. Roger G. Kennedy (2002) suspects that Burr was planning an invasion of New Spain, but that his goal was to conquer this territory for the USA. In this context it seems ironic that the annexation of Texas to the United States, 30 years after the "Burr Conspiracy", went according to the plan that Burr was still accused of treason: American settlers, adventurers and land speculators created an independent state here in 1836 on Mexican soil and provoked a war, but the protagonists of this episode like Sam Houston and Davy Crockett went down as heroes in American history. When Burr heard of this “Texas Revolution” shortly before his death, he is said to have exclaimed: “You see? I was right! I was only there 30 years early! What was treason 30 years ago is now patriotism! "

Peter Charles Hoffer (2008), on the other hand, suspects a kind of complicated investment fraud behind Burr's expedition : With increasingly cocky promises, Burr enticed more and more interested parties to lend him more and more money. The expedition would therefore have been nothing more than a staffage that was not supposed to reach its destination, whatever it was supposed to be . The fact that new rumors spread about the extent of his invasion plans or the size of his "army" would have been in Burr's own interest at first, since he was able to fool potential investors (such as Blennerhassett) about the likely success of his project. Finally, Joseph Wheelan (2005) sees the trial of Burr as part of a ruthless campaign by Jefferson against his political opponents, which, in addition to Burr, primarily hit the federal judges of the federal courts.

Exile in Europe

After the trial, Burr was confronted with a hostile public: when he wanted to spend the night in Baltimore on his way home to New York , a mob of around 1,500 angry citizens found themselves on the streets, including straw dolls from Burr, Blennerhassett, Martin and Marshall hung up on a gallows and then burned to death - Burr fled the city in a hurry. He spent the next time in seclusion with friends until he finally embarked for England in June 1808. He recorded his four years in Europe in a detailed diary that he wrote for his daughter Theodosia. In addition to his numerous amorous adventures, he describes how he unsuccessfully sought the support of European powers for his project - which he only vaguely refers to as "X". The memories of Jeremy Bentham , with whom Burr became a close friend during his time in London, are informative for the concrete form of "X" . Burr, according to Bentham, “actually intended to rise to the position of Emperor of Mexico.” At first, Burr tried his luck with British Foreign Minister Viscount Castlereagh , but the timing for the project to warm Britain to a conquest of the Spanish colonies was extremely unfavorable: Shortly before that, the popular uprising against Napoleonic rule had begun in Spain, which was soon vigorously supported by the British and finally culminated in the Peninsula Wars. Castlereagh dismissed Burr's request, and on April 4, 1809, Burr was arrested in the middle of the night and informed that he had to leave the country immediately; probably with this action the British authorities complied with a request of the Spanish ambassador. Originally, Burr was supposed to be deported to Heligoland , but he was able to negotiate that he could travel to Sweden instead .

After six months in Sweden and Denmark , Burr set his hopes on getting Napoleon excited about his plans. The project has long since failed because the French authorities refused to issue him visas for the areas they controlled. He had to stay in Altona for two months until the French consul Fauvelet de Bourrienne allowed him access to Hamburg and the onward journey to Frankfurt , where he had to wait a few more weeks before he could pick up his visa for France in Mainz . On February 16, 1810, he finally reached Paris. Here he met with mixed reactions: While the still influential former Foreign Minister Talleyrand refused to receive Burr, as Burr was considered to be the murderer of the "greatest man of our time" - Hamilton - the incumbent Nompère de Champagny received him several times and gave him gifts quite hearing. The French archives show that Burr proposed reintegration of Louisiana into France, but also that he by no means called for the destruction of the United States, as he has often been accused of. Burr prepared a detailed synopsis of his plans for Napoleon, but it is not known whether it ever attracted the emperor's attention. After some time, Burr received no more answers to his inquiries from the ministry - apparently Napoleon believed the rumors that Burr was involved in the plans of Police Minister Joseph Fouché , who had been deposed in the summer of 1810 and then fled, and that peace was negotiated behind the back of the emperor Bring about Great Britain.

With this, Burr's plans to conquer Spanish America were finally shattered. As a result, he lived in increasing poverty and constantly on the run from creditors in Paris. The French authorities refused to allow him to leave the country without giving any further reasons. When he turned to the American embassy to apply for a passport with which he hoped to be able to leave the country, he was also denied this - the consul responsible in Paris was Alexander MacRae, who four years earlier had been one of the prosecution's lawyers Burr had been on trial. It was not until the summer of 1811 that Burr was able to travel to the Netherlands, from where he went to England, although he was still persona non grata there. His return trip to the USA threatened to fail because of his sheer poverty. In April 1812 he finally went to the Alien Office and explained his situation. Without hesitation, the authorities wrote him a check and arranged for his departure on the next possible sailor. On April 4, 1812, Burr, disguised with a wig and a mustache, re-entered American soil under the false name "Adolphus Arnot".

Return to New York, final years and death

After Burr learned that a trial against him in Ohio in 1808 had been suspended, he took off his disguise. He borrowed $ 10 and reopened a law firm in New York. His reputation as an able lawyer had survived all scandals, and thanks to numerous assignments, he was soon able to have a decent income again - although he would have to spend a lot of time until the end of his life to keep old and new creditors at bay.

In the year of his return, however, he also suffered personal strokes of fate: his eleven-year-old grandson died in July. A few months later he wanted to initiate a reunion with his daughter Theodosia, whose husband Joseph Alston had been elected governor of South Carolina in 1812. On the way from Charleston to New York, her sailor, the Patriot , disappeared without a trace. It is plausible that the ship sank in a storm, but rumors persisted in the years that followed that pirates (suspected Dominique You ) had hijacked the ship and either murdered or kidnapped Theodosia. Even in the 20th century, its disappearance spurred many speculations and provided material for some pirate romances. The loss hit hard Burr, but he was looking for in the next few years solace in ever new children and wards to include in his budget, including the three stepdaughters his deceased client Medcef Eden who titled him as "Papa". With some of the other children he gathered around himself, including about Aaron Columbus Burr (1808-1882), it is proven or at least likely that he was actually their biological father; up to old age Burr followed the not unfounded call to be a "man of women". In his will in 1836, at the age of 80, he bequeathed part of his fortune to two of his daughters, one of whom was only two years old; his biographer James Parton notes that Burr's paternity must be rejected as "physiologically impossible".

The reputation of being Hamilton's murderer and a traitor to his own country haunted him to the end of his life. He was often attacked on the street, mothers showed him to their children on the street as an example of what happens to the "bad men". When Burr was visiting a moving wax museum on a trip to the country , he discovered that his duel with Hamilton was depicted in one of the tableaus. The scene was signed with the verses "O Burr, O Burr, what have you done? / You shot the great Hamilton dead / You hid behind a thorn bush / and shot him dead with a large pistol!"

On July 1, 1833, at the age of 77, Burr married a second time. The marriage caused quite a stir, with his bride being the 58-year-old widow Eliza Bowen Jumel , who had started her career as a prostitute at a young age, had amassed millions of dollars in fortune with a keen business acumen, and is now the richest woman in the United States States was true. As soon as the marriage was concluded, Burr began to spend his wife's money, so that Jumel soon sued for the dissolution of the marriage. As a divorce attorney, she hired, ironically, Alexander Hamilton Jr. On September 14, 1836, the marriage was legally divorced; Aaron Burr died on the same day at his hotel on Staten Island. He was buried next to his father and grandfather in the Princeton College cemetery.

reviews

To this day, Burr is one of the most controversial figures in American history; In 2008, for example, Time magazine named him the “worst vice president” in American history. Although he was acquitted in the treason trial in 1807, he is still considered in the public consciousness, alongside Benedict Arnold, as the epitome of the traitor to his own country. One of the most flowery speeches by the prosecution at the Richmond trial, William Wirts Who is Blennerhassett? , has been included in numerous school books as a prime example of rhetoric. Generations of American school children got to know Burr as a "snake" that invaded the peaceful "Garden of Eden" that Harmann Blennerhassett had created on his river island in Ohio. The portrayal of Burr as a diabolical power extends into the 20th century; so in 1931 a Booth Tarkington drama entitled Colonel Satan, or A Night in the Life of Aaron Burr premiered on Broadway. It is particularly important that Burr was enemies during his lifetime with many of the “ founding fathers ” - Washington, Jefferson and Hamilton - who are present in the collective consciousness as saints of the American “ civil religion ”. In the 19th century, Burr's life was processed in a variety of often lurid or maudlin poems, dramas, essays, pamphlets and novels, mostly unfavorable. Recurring tropes are, in addition to the Fall, the portrayal of Burr as Cain , as the American Catiline or as an insatiable lecher. He was sometimes used as a "hero" in clearly pornographic novels (for example in the anonymous The Amorous Intrigues and Adventures of Aaron Burr , 1861). In the 20th century, the processing of the "Burr Conspiracy" by Eudora Welty ( First Love , 1943) and Gore Vidal ( Burr , 1973) should be mentioned. Vidal's novel is to be highlighted as an early example of a changed, positive Burr image. Vidal, who carried out intensive research in historical archives for the novel, suggests that it was the charge of an incestuous relationship with his daughter Theodosia that caused Burr Hamilton to challenge for a duel.

Most historians' judgment of Burr is negative. Henry Adams apparently wrote a biography of Burr in 1881, but burned the manuscript after his publisher initially refused to publish it. The Burr conspiracy, however, occupies a large space in Adams' nine-volume History of the United States During the Administrations of Thomas Jefferson and James Madison (1889-1891), which pioneered the history of the early Republic. In it, Adams consistently portrays Burr as an unscrupulous opportunist and at one point describes him as the “Mephistopheles of politics.” Burr's defenders include, above all, his biographers. Barely a year after his death, his long-time friend Matthew L. Davis published his first apologetic biography of Burr, James Parton (1892) also portrayed Burr in a benevolent manner. In the standard two-volume biography of Milton Lomask (1979-1982), many of the are against Burr The allegations raised are relativized or invalidated, also in the most recent biography of Nancy Isenberg (2007).

The first publication of Burr's collected writings in 1978 (on microfilm) and 1983 (printed) by a group of historians around Mary-Jo Kline did little to clear up the numerous inconsistencies in Burr's biography. Many of his papers disappeared with his daughter Theodosia in the Atlantic, numerous other documents were destroyed by Matthew L. Davis, Burrs biographer and estate administrator. While historians can fall back on extensive collections of sources in their work on other “founding fathers”, Burr's collected writings only take up two volumes. Many of them deal with money deals, land speculation, and haggling. Historian Gordon S. Wood could not locate a letter in it that contained even the beginning of a political philosophy, not even a document showing Burr's position on the constitutional question or on Hamilton's economic policy of the 1790s. For Burr, politics seemed to be a game from which - in his own words - " fun, honor & profit" could be hit. This is where Wood sees the major difference to the other founding fathers and Burr's "real betrayal": While Jefferson or Hamilton, for example, portrayed politics as a virtuous, selfless service to the good of the nation, Burr seems to have been resistant to this noble, enlightened ideology . Through his unprincipled and often selfish behavior, Burr's political ascent meant nothing less to Jefferson and Hamilton alike than a danger to the “Republican experiment,” and therefore to all freedoms won in the revolution.

literature

sources

- Mary-Jo Kline and Joane W. Ryan (Eds.): Political Correspondence and Public Papers of Aaron Burr. 2 volumes. Princeton University Press, 1983.

- Reports of the Trials of Colonel Aaron Burr. 2 volumes. Hopkins and Earle, Philadelphia 1808. (Digital copies: Volume I ; Volume II )

- Matthew L. Davis (Ed.): The Private Journal of Aaron Burr, During His Residence of Four Years in Europe; With Selections from His Correspondence. 2 volumes. Harper & Brothers, New York 1838. (Digital copies: Volume I , Volume II )

Secondary literature

- Thomas Abernathy: The Burr Conspiracy. Oxford University Press, New York 1954.

- Henry Adams : History of the United States of America During the First Administration of Jefferson. 2 volumes. Charles Scribner's Sons, New York 1903.

- Francis F. Beirne: Shout Treason: The Trial of Aaron Burr. Hastings, New York 1959.

- Matthew L. Davis : Memoirs of Aaron Burr. With Miscellaneous Selections from his correspondence. 2 volumes. Harper & Brothers, New York 1837. (Digital copies: Volume I ; Volume II )

- Thomas Fleming: Duel. Alexander Hamilton, Aaron Burr, and the Future of America. Basic Books, New York 1999.

- Marie B. Hecht and Herbert S. Parmet: Aaron Burr: Portrait of an Ambitious Man. Macmillan, New York 1967.

- Peter Charles Hoffer: The Treason Trials of Aaron Burr. University of Kansas Press, Lawrence 2008, ISBN 978-0-7006-1591-9 .

- Nancy Isenberg : Fallen Founder. The Life of Aaron Burr. Viking, New York 2007, ISBN 978-0-670-06352-9 .

- Roger G. Kennedy: Burr, Hamilton, and Jefferson: A Study in Character . Oxford University Press, New York 2000, ISBN 0-19-514055-9 .

- James E. Lewis Jr .: The Burr Conspiracy: Uncovering The Story of an Early American Crisis . Princeton University Press, Princeton NJ 2017, ISBN 978-0-691-17716-8 .

- Milton Lomask: Aaron Burr. 2 volumes:

- Vol. I: The Years from Princeton to Vice President 1756-1805. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, New York 1979.

- Vol. II: The Conspiracy and Years of Exile 1805-1836. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, New York 1982.

- Buckner F. Melton: Aaron Burr: Conspiracy to Treason. John Wiley and Sons, New York 2001.

- R. Kent Newmyer: The Treason Trial of Aaron Burr: Law, Politics, and the Character Wars of the New Nation. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2012, ISBN 978-1-107-02218-8 .

- Charles J. Nolan: Aaron Burr and the American Literary Imagination. Greenwood Press, Westport 1980.

- James Parton : The Life and Times of Aaron Burr. Mason Brothers, New York 1858. ( digitized version )

- Arnold A. Rogow: A Fatal Friendship: Alexander Hamilton and Aaron Burr. Hill and Wang, New York 1998.

- Nathan Schachner : Aaron Burr: A Biography. AS Barnes, New York 1961.

Novels

- Gore Vidal : Burr. A Novel (1973), German Burr , translated by Günter Panske , Goldmann, Munich 2001, ISBN 3-442-72846-0 .

- Michael Kurland : The Whenabouts Of Burr (1975), dt. Where is Aaron Burr? , translated by Thomas Ziegler , Ullstein, Frankfurt am Main / Berlin / Vienna 1983, ISBN 3-548-31058-3 .

Web links

- Aaron Burr, 3rd Vice President (1801-1805) (United States Senate Historical Office)

- Aaron Burr in the Biographical Directory of the United States Congress (English)

- Literature by and about Aaron Burr in the catalog of the German National Library

- Aaron Burr in the database of Find a Grave (English)

Individual evidence

- ^ "I have never known, in any country, the prejudice in favor of birth, parentage, and descent more conspicuous than in the instance of Colonel Burr." Letter from John Adams to James Lloyd, February 17, 1815.

- ^ Stanley Elkins and Eric McKitrick : The Age of Federalism. Oxford University Press, New York 1993. pp. 81-85.

- ↑ Isenberg, pp. 27-28.

- ↑ Isenberg, pp. 27-28; Lomask I, pp. 41-42.

- ↑ Isenberg, pp. 33-34, Lomask, pp. 43-44.

- ↑ Lomask I, pp. 49-50.

- ↑ Lomask I, 50-55.

- ↑ z. B. Lomask I, pp. 55-56; Isenberg, p. 43.

- ↑ Lomask, pp. 56-59.

- ↑ Lomask I, pp. 59-63.

- ↑ Lomask I, pp. 75-82; Isenberg, p. 88.

- ↑ Lomask I, p. 93.

- ↑ Lomask I, pp. 85-93; Isenberg, pp. 189-196.

- ↑ Lomask, S. 120th

- ↑ Lomask I, pp. 131-132; Isenberg, p. 100.

- ↑ Lomask, pp. 133-134.

- ↑ Lomask, pp. 134-135, Isenberg, pp. 104-105.

- ↑ Lomask, pp. 139-144; Isenberg, pp. 105-106. Detailed presentation in: Alfred F. Young, The Democratic Republicans of New York: The Origins. University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill 1967. pp. 187-192.

- ↑ Isenberg, p. 107.

- ↑ Young, pp. 197-198.

- ↑ Young, p. 329.

- ↑ Young, pp. 278-279, 430-431.

- ↑ Isenberg, pp. 109-113.

- ↑ Young, pp. 324-330.

- ↑ Hamilton to Unknown, September 21, 1792. Quoted in Lomask, p. 174.

- ↑ Lomask I, pp. 156-157.

- ↑ Isenberg, pp. 132-134.

- ↑ Isenberg, pp. 135-137.

- ↑ Isenberg, p. 131.

- ↑ Lomask, S. 158th

- ↑ Lomask I, p. 183.

- ↑ Young, pp. 546-551; Isenberg, pp. 146-154.

- ↑ Isenberg, pp. 158-159.

- ↑ Lomask I, pp. 209-213.

- ^ Wood, p. 288.

- ↑ Lomask I, pp. 221-230.

- ↑ Lomask, pp. 237ff.

- ↑ Elkins and McKitrick, p. 748.

- ↑ For heaven's sake let not the Federal party be responsible for the elevation of this man! Quoted in: Gordon S. Wood: Empire of Liberty: A History of the Early Republic, 1789-1815. Oxford University Press, New York 2009.

- ↑ I never, indeed thought him an honest, frank-dealing man, but considered him as a crooked gun, or other perverted machine, whose aim or stroke you could never be sure of. Letter to William Branch Gile , April 20, 1807. Quoted in: RB Bernstein: Thomas Jefferson . Oxford University Press, New York 2005, p. 163.

- ↑ Lomask, p. 307.

- ↑ Lomask, pp. 314-322; Isenberg, pp. 247-252.

- ^ Never in the History of the United States did so powerful a combination of rival politicians unite to break down a single man, as that which arrayed itself against Burr. For as the hostile circle gathered about him, he could plainly see not only Jefferson, Madison, and the whole Virginia legion, with Duane and his "Aurora" at their heels; not only DeWitt Clinton and his whole family, with Cheetham and his "Watchtower" by their side; but strangest of all companions, Alexander Hamilton himself, joining hands with his own bitterest enemies to complete the ring. Henry Adams: History of the United States During the First Administration of Jefferson (1903). Quoted below from the one-volume edition of the Library of America , New York 1986. p. 226.

- ↑ Lomask, p. 323.

- ↑ Lomask, pp. 309-312.

- ↑ Adams, p. 192: “This dramatic insult, thus flung in the face of the President and his Virginia friends, was the more significant to them because they alone understood what it meant. To the world at large the toast might seem innocent; but the Virginians had reason to know that Burr believed himself to have been twice betrayed by them, and that his union of honest men was meant to gibbet them as scoundrels. "

- ↑ see in particular: Garry Wills: Negro President: Jefferson and the Slave Power. Houghton Mifflin, Boston 2003. pp. 127-139.

- ^ Thomas P. Slaughter: Conspiratorial Politics: The Public Life of Aaron Burr. In: New Jersey History 103, 1985, pp. 69-81.

- ↑ Lomask I, p. 346ff.

- ↑ Merrill Lindsay: Pistols Shed Light on Famed Duel. In: Smithsonian 7/8, November 1976, pp. 94-98.

- ↑ Isenberg, pp. 272-279; Lomask I, pp. 362-366.

- ^ Minutes of the speech in the Annals of Congress

- ↑ Isenberg, pp. 279-282.

- ↑ For example the summary in: Elkins and McKitrick, p. 745.

- ↑ Ron Chernow : Alexander Hamilton . Penguin, New York 2004, pp. 562-568

- ↑ Lomask II, p. 17.

- ↑ Lomask II, pp. 49-52.

- ↑ Lomask II, p. 72 ff.

- ↑ Lomask II, pp. 100-105.

- ↑ Lomask II, pp. 168-169.

- ^ So Jefferson in his address to Congress on January 22, 1807 ( Memento of August 12, 2011 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Article III, paragraph 3 of the United States Constitution after translation (PDF; 201 kB) on the pages of the American Embassy in Germany.

- ↑ On Jefferson's role in the trial, see for example Hoffer, pp. 123–125, pp. 142–143.

- ↑ On the subpoena duces tecum see Hoffer, pp. 134–140.

- ↑ Assessment based on: Hoffer, p. 36.

- ↑ See the overview of the research literature in: Hoffer, pp. 199–206.

- ↑ Sean Wilentz: The Rise of American Democracy. Norton, New York 2005, pp. 128-130.

- ↑ Isenberg, pp. 282-283.

- ↑ You see? I was right! I was only thirty years too soon! What was treason in me thirty years ago, is patriotism now! Reported in: Parton, p. 670.

- ↑ Hoffer, pp. 189–193.

- ↑ Isenberg, p. 368.

- ↑ He really meant to make himself emperor of Mexico. Quoted in: Lomask II, p. 309.

- ↑ On Burr in England, see Lomask II, pp. 302-315.

- ↑ During Burr's time in Germany and France see Lomask II, 325–351.

- ↑ Lomask, pp. 351-357.

- ^ Richard N. Côté: Theodosia Burr Alston: Portrait of a Prodigy. Corinthian Books, Mount Pleasant 2002, pp. 307ff.

- ↑ "Oh Burr, oh Burr, what hast thou done? Thou hast shooted dead great Hamilton./ You hid behind a bunch of thistle / And shooted him dead with a great hoss pistol. " Ron Chernow : Alexander Hamilton. Penguin, New York and London 2004. p. 721.

- ↑ Isenberg, pp. 400-404.

- ↑ Time: America's Worst Vice Presidents , undated, but probably 2008.

- ↑ Lomask II, p. 236.

- ↑ On Burr in the literature, see the monograph by Charles J. Nolan (1980)