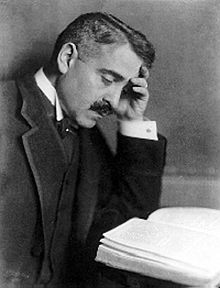

Aby Warburg

Aby Moritz Warburg (born June 13, 1866 in Hamburg ; died October 26, 1929 there ) was a German-Jewish art historian and cultural scientist and the founder of the Warburg library for cultural studies . The subject of his research was the afterlife of antiquity in the most diverse areas of Western culture up to the Renaissance. Iconography was established by him as an independent discipline in art history .

Life

origin

Aby Warburg came from the wealthy Warburg banking family . His ancestors had immigrated from Bologna to Germany in the 17th century to the city of Warburg in Westphalia and had adopted the latter's name as their family name. In the 18th century the Warburgs moved to Altona . Two Warburg brothers founded the MM Warburg & Co banking house in Hamburg in 1798 , which is now back in Hamburg.

Aby Warburg was the first of seven children of the then head of the Hamburger Bank, Moritz M. Warburg , and his wife Charlotte born. Oppenheim born. While Aby Warburg was interested in literature and history at an early age, his brothers Max , Paul , Felix and Fritz became bankers. You held political offices in Germany and after emigrating to the USA.

Childhood and youth

Warburg grew up in a conservative Jewish family . From the point of view of his family, his difficult character traits, an unstable and erratic temperament, irascibility and lack of mental stability became apparent early on. Since his health was always very fragile, his behavior was tolerated by the family. Warburg revolted early on against the religious rituals strictly observed in the family , and he refused to follow his family's career plans: he neither wanted to become a rabbi , as his grandmother wanted, nor a doctor or a lawyer. His decision to study art history met with bitter resistance from his relatives, but Warburg prevailed with his plan. As his brother Max reports, Aby Warburg had been a keen reader from a young age. Max told the anecdote that became part of the Warburg legend:

“When he was thirteen he offered me his firstborn right. As the elder, he was destined to join the company. I was twelve at the time, not very ready for thought, and I agreed to buy the firstborn right from him. But he didn't offer it to me for a lentil dish, but asked me to promise that I would always buy him all the books he needed. After a very brief consideration, I agreed to this. I said to myself that after all, Schiller, Goethe, Lessing, perhaps also Klopstock, could always be paid by me if I were in the business, and unsuspectingly gave him, as I must admit today, a very large blank credit. The love for reading, for books ... was his great early passion. "

The fact is, the Warburg Abys family always financed expensive book purchases.

Just like his two brothers Max and Paul , he attended the "Realschule des Johanneum ", which at that time was still located in the combined museum and school building on Steintorplatz. On "Michaelis 1885" he passed his Abitur there.

Education

In 1886 he began studying art history , history and archeology in Bonn, where he heard ancient religious history from Hermann Usener , cultural history from Karl Lamprecht and art history from Carl Justi . He continued his studies in Munich and with Hubert Janitschek in Strasbourg, who was in charge of his dissertation on Botticelli's pictures The Birth of Venus and Spring . From 1888 to 1889 he stayed at the Art History Institute in Florence to study the sources for these pictures. He was now also interested in the possibilities of applying scientific methods in the humanities . The dissertation was submitted in 1892 and printed in 1893. With Warburg's investigation, a new method, iconography or iconology , was introduced into the subject of art history. His dissertation is considered a milestone in the history of the subject.

After receiving his doctorate , Warburg studied two semesters at the medical faculty of the University of Berlin , where he attended lectures on psychology. During this time he made another trip to Florence.

Trip to the USA

At the end of 1895 to 1896 he traveled to the United States , first to New York for the wedding of his brother Paul and Nina Loeb, daughter of the banker and philanthropist Salomon Loeb . He was drawn to the west, initially making contact with the Smithsonian Institution . Frank Hamilton Cushing , who had conducted field research with the Zuñi in New Mexico , deeply impressed him. Warburg also went to the southwest of the USA, to various pueblos in New Mexico, visited Acoma , Laguna , San Ildefonso , where he photographed an antelope dance, and Cochiti , most recently Zuñi. Cleo Jurino from Cochiti recorded Warburg's cosmology . This drawing is now in the Warburg Institute in London.

Warburg was then able to stay with the Hopi in Arizona for some time and study their culture. First in Keams Canyon , where he carried out his drawing experiment with Hopi school children, and then with the Mennonite missionary Heinrich R. Voth, who taught him a lot about the Hopi religion and made it possible for him to participate in rituals. Voth was a talented anthropologist , if his methods seem brutal today. Warburg later justified his field studies with, among other things, a “genuine disgust” for the “aesthetic history of art”. "The formal consideration of the picture - unconceived as a biologically necessary product between religion and the practice of art - [...] seemed to me to evoke a sterile word business [...]" Warburg made notes about the strange analytical bird ornamentation of the Hopi potter Nampayo and about the metaphysical meaning of the Kachinas . He saw a Hemis-Kachina dance by the Hopi and was even able to watch the mask dancers in their resting place and thus study the mask being vividly. Voth took a snapshot of Warburg with his mask on.

After his return, Warburg held slide shows in Hamburg and Berlin. He later bequeathed his collection of Pueblo objects and Hopi children's drawings to the Hamburg Völkerkundemuseum . Warburg's evaluation of children's drawings is an early example of the application of this method in ethnology . His notes on the snake ritual remained unprocessed for the next twenty years.

Florence

In 1897 Warburg married the painter and sculptor Mary Hertz , daughter of a Hamburg shipowner and senator who was also a member of the Synod of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in Hamburg , against his father's will . The couple had three children: Marietta (1899–1973), Max Adolph (1902–1974) and Frede Charlotte Warburg (1904–2004).

In 1898 Warburg and his wife moved into an apartment in Florence . Although Aby Warburg was repeatedly plagued by depression , the couple led a lively social life. The lively Florentine circle included the sculptor Adolf von Hildebrand , the writer Isolde Kurz , the English architect and antiquarian Herbert Horne , the Dutch Germanist André Jolles and the Belgian art historian Jacques Mesnil . The most famous Renaissance specialist of the time, the American Bernard Berenson , was also in Florence at the time. On the one hand, the conversations in this educated and art-loving international community in Florence were stimulating for Warburg. On the other hand, he rejected any sentimental aestheticism in relation to works of art. He also hated the educational travelers with their uncritical enthusiasm for art , which he called “supermen in the Easter holidays”. This attitude was also evident in his notes and writings in the form of polemical attacks against enthusiasm for art and the glorification, vulgarized in the course of Burckhardt's interpretation of the Renaissance, of a heightened individualism allegedly cultivated in the Renaissance - an individualism that in the ideas of his contemporaries likes to think about merged with the Übermenschen Nietzschean stamp.

In the Florentine years Warburg examined the economic and private living conditions of the Renaissance artists and their clients as well as the economic situation in Florence during the early Renaissance and the problems of the transition from the Middle Ages to the Early Renaissance. Another result of his time in Florence was the series of lectures on Leonardo da Vinci , held in the Hamburger Kunsthalle in 1899 . In the lectures he went a. a. on Leonardo da Vinci's study of medieval bestiaries as well as on his examination of the classical theory of proportions according to Vitruvius .

He also dealt with the references to antiquity observed in Botticelli in the depiction of the clothing of pictorial figures. Female clothing is almost of symbolic importance in Warburg's famous essay, inspired by discussions with Jolles, on the nymphs and the figure of the maid in Ghirlandaio's fresco in Santa Maria Novella in Florence. The contrast between the stiff matrons, forced into tight robes and the lightly clad, swift-footed maid, appears in the picture as an illustration of the virulent discussion around 1900 about appropriate behavior for a woman and about clothing that frees her from the constraints and rules of propriety and liberated the propriety ideas of a reactionary bourgeoisie .

Return to Hamburg

In 1902 the family returned to Hamburg and Warburg presented the results of his Florentine research in a series of lectures, but initially did not accept a professorship or any other academic position. He became a member of the administrative board of the Völkerkundemuseum , promoted the establishment of the Hamburg Scientific Foundation (1907) together with his brother Max and promoted the establishment of a Hamburg university. In 1912 he turned down a professorship at the University of Halle . Instead, he was made an honorary professor by the Hamburg Senate at an early stage at the University of Hamburg , which was still under construction and was finally founded in 1919. Already at this time there were signs of his mental illness, which impaired his research and teaching activities.

Star belief and astronomy

Warburg's exploration of the astrological world of images began with his lecture on a calendar by the Hamburg printer Stephan Arndes in 1908. As with his notes on the Hopi snake ritual and the later Kreuzlingen lecture, he was fascinated by the power of symbols in astrology and the tension between man's fear of demons , overcoming it through the creation of images and symbols on the one hand, and the simultaneous development of rationality from this very thing Demon fear on the other hand:

“In astrology, two very heterogeneous spiritual powers, which logically only have to feud with one another, have come together in an irrefutable factual way to form a 'method': M a t h e m at i k, the finest tool for abstract thinking, with demons for the most primitive form of religious causation. While the astrologer grasps the universe clearly and harmoniously on the one hand in the sober system of lines [...], an atavistic superstitious shyness in front of his mathematical tables inspires him to these star names, with which he treats as with numerals, and which are actually demons that he does has to fear. "

Warburg's concern with astrology was also about the afterlife of antiquity . He examined the astronomy of the Greeks, who did not yet differentiate between astronomy and astrology , and asked about the oriental and ancient Egyptian roots of Greek astronomy. He assumed that the population of the starry sky arose by means of mythological figures from the impulse to name the conspicuous points of light, fixed stars and star figures with god names in the course of a rational, mathematical recording of the sky. These are still used in astronomy today and when they were used as symbols they developed an unexpected power. He studied the genesis of the astrological world of imagery, its ways, development and change in the Middle Ages (called late antiquity by Warburg) including its entry into medieval stone magic and medicine and its rebirth in the shape and beauty of ancient Olympic gods in the Italian Renaissance and their continued life in the superstition of the stars of astrology to the present day.

The results of his study of astrology are only partially published. In addition to the essay On Images of the Planet Gods in the Low German Calendar of 1519 [1910], the lectures An astronomical representation of the sky in the old sacristy of San Lorenzo and Pagan ancient prophecies in words and images in Luther's time [1920], in which he was among the reformers who he regarded as pioneers in the development of the occidental enlightenment , still saw the belief in heavenly omens for earthly upheavals, catastrophes, extraordinary events rooted. In his essay, for example, he dealt with Melanchthon's efforts to move Luther's birthday to 1484, the year of an unusual planetary constellation in which, calculated for years in advance, “a new epoch in occidental religious development was to come”. The comprehensive interpretation of the monthly pictures in the Palazzo Schifanoia in Ferrara [1912] resulted from reading Franz Boll's book Sphaera and viewing numerous astrological documents and manuals. In 1927 another essay on orientalizing astrology followed . The specialist library, which was continuously expanded in the course of his research, was part of Warburg's Hamburg Library of Cultural Studies and is now located in the Warburg Institute of the University of London . It is likely to be the most extensive special library on astrology.

The mental illness

Warburg, who was seriously ill with typhoid at the age of six , remained in unstable physical and mental health from that time on. From childhood he was prone to nervous states, and when exposed to stress he quickly reacted with exaggerated and excited behavior. A serious illness in his mother in 1874 increased his mental instability. Time and again he was paralyzed by depression in his scientific work. In November 1918 Warburg, who perceived the post-war period with its serious economic and social problems as a phase of elementary threat to himself and his family, finally broke out into severe psychosis , in which he lost control of himself and his situation. When he threatened to kill himself and his family for fear of the chaotic political situation, he was admitted to a psychiatric clinic.

After his condition had not improved over the next two years, he was taken to the Bellevue sanatorium in Kreuzlingen on April 16, 1921 , which was directed by the psychiatrist Ludwig Binswanger . In his medical reports at Warburg, Binswanger documented delusions, aggressiveness towards the staff, phobias and compulsive hygiene rituals. In the course of the treatment, he also had balanced days on which he could receive visits from his colleagues and friends, although initially there was no permanent improvement. In 1922 his assistant Fritz Saxl began his scientific work with Warburg again, in the hope that this would stabilize his mental state. At the urging of the family, another psychiatrist, Emil Kraepelin , was consulted the following year , who changed the diagnosis of schizophrenia to manic-depressive illness. This opened the hope of a cure for Warburg and a final discharge from the institution. According to the assessment of his doctors, Warburg was always aware of his illness, he described himself as "incurably schizoid", but also had phases of mental clarity and creative productivity during the illness.

The first sign of psychological stabilization was the processing of his notes on the Hopi Indians. Together with Saxl he worked out a lecture on the "snake ritual" of the Hopi, which he gave on April 21, 1923 to patients and doctors at Bellevue. The next year in Bellevue there were a series of intensive discussions with the philosopher Ernst Cassirer about the viability of his method of a “cultural-psychological view of history”. In Cassirer and Saxl, Warburg experienced understanding, empathetic and equal interlocutors who, as well as the friendly and trusting relationship with the Binswangers family and the special environment of Binswanger's clinic, may have contributed to a process of self-healing at Warburg.

Mnemosyne

In August 1924 Warburg was released from the clinic. He began working on his picture atlas Mnemosyne ( Mnemosyne is the Greek patron goddess of memory and the art of remembrance). The full title was: Mnemosyne, series of images to investigate the function of pre-formed ancient expressive values in the representation of eventful life in the art of the European Renaissance . The aim of the project was to use images to illustrate the diverse survival of antiquity in European culture. Ernst Gombrich noted in his Warburg biography that Warburg's work ... described the fate of the gods in astrological tradition and the role of the ancient pathos formula in post-medieval art and culture .

At Saxl's suggestion, Warburg used wooden frames covered with black fabric, to which he attached photographs of images with pins, each of which was grouped and regrouped around a specific topic or focus, as basically corresponded to Warburg's working method. In doing so, he did not limit himself to classic research objects from art history, but also took into account advertising posters, postage stamps, newspaper clippings or press photos of current events such as the signing of the Concordat by Benito Mussolini and a representative of the Curia . The boards initially served as a means of demonstration for lectures and exhibitions that took place in the reading room of the Hamburg library. Warburg was the first to introduce reproductions as a didactic tool in exhibitions and as an aid to art history. The atlas ultimately consisted of over 40 boxes with approx. 1500 to 2000 photos - all the figures differ greatly in the literature - which partially covered the panels to the edge and were not provided with captions or comments.

Between 1925 and 1929 Warburg also held individual lectures and seminars, but these took place in a more or less private circle or in his library.

Warburg died of a heart attack on October 26, 1929. He was buried in the Ohlsdorf cemetery.

The Mnemosyne project remained unfinished. The work was not published and the original plates have not been preserved. They may have been lost when the library moved to London. The photographic reproductions that Saxl had arranged give an impression of the original plates. Only in 1993 and 1994 was a reconstruction of the atlas exhibited in Vienna and Hamburg. An annotated edition was published as part of a complete edition of Warburg's writings by Martin Warnke, along with a detailed commentary. The publisher of the work also questions whether the reconstruction corresponds to Warburg's intentions.

The Warburg Library for Cultural Studies

Around 1901, Warburg began systematically collecting books with financial support from his family. The decision for an interdisciplinary cultural studies library had matured during his studies in Strasbourg, when he had to look for literature in many specialized libraries for his dissertation. In 1909 Warburg moved into the house at Heilwigstrasse 114 in Hamburg, where he housed the growing collection and lived until the end of his life. With foresight, he also acquired the neighboring property at Heilwigstrasse 116. Although he hired assistants to look after the library, the organization still corresponded to that of a private scholarly library. In 1920 the library contained around 20,000 volumes.

In order to make the collection more accessible for research, the establishment of research grants for young scientists was considered. Fritz Saxl and Gertrud Bing began a comprehensive reorganization with the aim of making it easier for the growing number of students to work with the library. The library changed from a private library to a public institution. It was financially secured even during the inflation by the reliable donations of the American Warburgs. Through the collaboration with the Hamburg University , founded in 1919, a group of scholars was formed who were closely connected to the cultural studies library. Among them were u. a. the philosopher Ernst Cassirer , the art historians Gustav Pauli and Erwin Panofsky , the orientalist Hellmut Ritter , the classical philologist Karl Reinhardt , the founder of the study of Jewish mysticism , Gershom Scholem , and the Byzantinist Richard Salomon .

After his return from the clinic in 1924, Warburg began building a new library on the property at Heilwigstrasse 116 next to his house. Both houses were designed for 120,000 volumes. In addition to the magazines, the new building contained a large oval reading room that was also used as a lecture hall. Work rooms, guest rooms, photo lab, bookbinding and state-of-the-art library technology completed the equipment. The new building, today's Warburg House , was opened in 1926. At the time of Warburg's death in 1929, the library contained 60,000 volumes.

After a period of constant growth and prosperity, the library came under pressure as a Jewish institution after the Nazis came to power . In the spring of 1933 Edgar Wind went to London for exploratory talks. With the help of the American Warburgs and generous private English donations, a move of the library to London could be financed. On December 12, 1933, two freighters loaded with book boxes, shelves and catalog boxes left the port of Hamburg and shipped the library to London. Thanks to the active support of Samuel Courtauld , the library could be housed in a bank building rented from Lord Lee of Farnham. What remained in Hamburg was a collection of 1,500 books, brochures and magazines as well as a large number of newspaper clippings on the First World War , which Warburg had been collecting since the beginning of the First World War. This archive material is considered lost. On November 28, 1944, the library was attached to the University of London (see Warburg Institute ).

On Warburg's position in the history of science

Aby Warburg is considered to be one of the most important stimuli in the humanities in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Although Warburg was valued in the academic world during his lifetime, he remained largely unknown and was almost forgotten during National Socialism and in the first years after the Second World War . The reception of his work was made more difficult by the fact that only a few of his texts were published at all and some were only available in editing by employees and only some in German. Most of his academic legacy consists of notes, card catalogs, approx. 35,000 letters, unfinished manuscripts and a library diary from 1926 to 1929. The move of the library and staff to London in 1933 made the young discipline of art history known in the Anglo-Saxon countries and encouraged the establishment of chairs at the elite universities there.

New interest in Warburg awoke with the publication of Gombrich's biography, which appeared in England in 1970 and was not printed in German translation until eleven years later. However, this work has always been controversial because of its gaps and a certain subjectivity. Since the 1970s, Martin Warnke and the Warburg Institute in London have been working on the edition of Warburg's estate. Since then, it has gradually been published in excellently accompanied editions and enables an intensive examination of the author's world of thought. With the iconology of the style analysis that dominated his time, Warburg added a new method. A number of his word creations have found their way into the terminology of art history. Terms such as thinking space , psychological energy reserves or the well-known pathos formula now lead a life of their own and are not always used in Warburg's intention. The often quoted sentence “God is in the details” refers to the exact study of very different documents, which only enables a deeper understanding of a picture in the context of its historical and social context. This method is a characteristic of work that emerged from the so-called "Warburg School".

Research into the Italian and German Renaissance was decisively shaped by Warburg and his cultural studies library. The afterlife of antiquity and the ancient gods, the coming into effect of pagan and ancient image concepts and magical image practices - especially in the Renaissance - which can be demonstrated without interruption in European culture and which is virulent in astrology to this day, was a topic to which he has drawn the attention of cultural studies. Warburg research received a new impetus in the course of the so-called Iconic Turn . In their demand for an interdisciplinary engagement with the world of images, with the knowledge and methods of philosophy , theology , ethnology , art history , media studies , cognitive science , psychology and natural sciences and the consideration and analysis of visual documents of all kinds, some authors see one in Warburg Precursor.

Awards named after Aby Warburg

Since 1980, the City of Hamburg has awarded the highly endowed Aby Warburg Prize for outstanding achievements in the humanities and social sciences every four years . It also awards a scholarship, also named after Aby Warburg, to scholars who work on interdisciplinary topics from the field of European cultural history. In addition, the Aby Warburg Foundation has been awarding the Science Prize since 1995 .

Fonts

- Collected Writings. Edited by the Warburg Library. Leipzig / Berlin, 1932, 2 volumes. Volume 1 , Volume 2 on Gallica .

-

Collected writings (study edition). Akademie Verlag, Berlin 1998-

- I, 1–2: The renewal of pagan antiquity. Cultural studies contributions to the history of the European Renaissance . (Reprint of the 1932 edition). Edited by Horst Bredekamp and Michael Diers . Berlin 1998.

- II, 1: The Mnemosyne picture atlas. Edited by Martin Warnke and Claudia Brink. Berlin 2000.

- II, 2: Series of pictures and exhibitions . Edited by Uwe Fleckner and Isabella Woldt. Berlin 2012.

- IV: Fragments on Expressionism . Edited by Ulrich Pfisterer and Hans Christian Hönes. Berlin 2015

- VII: Diary of the Warburg Library of Cultural Studies . Edited by Karen Michels and Charlotte Schoell-Glass. Berlin 2001.

- Aby Warburg. Works in one volume. Edited and commented on by Martin Treml, Sigrid Weigel and Perdita Ladwig on the basis of the manuscripts and personal copies . Suhrkamp, Berlin 2010, ISBN 978-3-518-58531-3 .

- The snake ritual. A travel report. With an afterword by Ulrich Raulff . Wagenbach, Berlin 1988. (5th edition. With an afterword to the new edition by Claudia Wedepohl. 2011, ISBN 978-3-8031-2672-6 )

literature

Bibliographies

- Dieter Wuttke : Aby-M.-Warburg-Bibliography 1866 to 1995. Work and effect; with annotations. Koerner, Baden-Baden 1998, ISBN 3-87320-163-1 .

- Björn Biester, Dieter Wuttke: Aby M. Warburg Bibliography 1996 to 2005: with annotations and addenda to the bibliography 1866 to 1995 . Koerner, Baden-Baden 2007, ISBN 978-3-87320-713-4 .

- Thomas Gilbhard: Warburg more bibliographico. In: Nouvelles de la République des Lettres . 2, 2008.

- Aby M. Warburg bibliography 2006 to 2010 (ongoing updates)

- Bibliography (until 2007) at engramma.it

Biographies

- Ernst H. Gombrich : Aby Warburg. New edition. Hamburg 2006. ( PDF, 2.014 kB )

- Bernd Roeck : The young Aby Warburg . Munich 1997.

- Carl Georg Heise : Personal memories of Aby Warburg. Edited and commented by Björn Biester and Hans-Michael Schäfer (Gratia. Bamberger Schriften zur Renaissanceforschung 43). Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 2005.

- Rainer Hering: Warburg, Abraham Moritz. In: Biographisch-Bibliographisches Kirchenlexikon (BBKL). Volume 13, Bautz, Herzberg 1998, ISBN 3-88309-072-7 , Sp. 330-350.

- Karen Michels: Aby Warburg - Under the spell of ideas. CH Beck, Munich 2007.

- Nicolas Bock, Peter Theiss-Abendroth: Aby Warburg - The picture thinker. (= Jewish miniatures . Volume 182). Hentrich & Hentrich, Berlin 2017, ISBN 978-3-95565-148-0 .

Individual representations

- Roland Kany: Mnemosyne as a program. History, memory and the devotion to the insignificant in the work of Usener , Warburg and Benjamin . Niemeyer, Tübingen 1987, ISBN 3-484-18093-5 , pp. 129-185.

- Silvia Ferretti: Il demone della memoria. Simbolo e tempo storico in Warburg, Cassirer, Panofsky . Marietti, Casale Monferrato 1984. Engl. Transl .: Cassirer, Panofsky and Warburg: Symbol, Art and History. Yale Univ. Press, London, New Haven 1989.

- Horst Bredekamp , Michael Diers , Charlotte Schoell-Glass (eds.): Aby Warburg. Files from the international symposium Hamburg 1990. VCH Acta humaniora, Weinheim 1991.

- Horst Bredekamp, Claudia Wedepohl: Warburg, Cassirer and Einstein in conversation: Kepler as the key to modernity. Wagenbach, Berlin 2015, ISBN 978-3-8031-5188-9 .

- P. Schmidt: Aby Warburg and the iconology . With an appendix of unknown sources on the history of the boarding school. Society for Iconographic Studies by D. Wuttke. 2nd Edition. Wiesbaden 1993.

- Wolfgang Bock : archetype and magical shell. Aby Warburg's theory of astrology. In: Bock: Astrology and Enlightenment. About modern superstitions. Metzler, Stuttgart 1995, pp. 265-254.

- Christiane Brosius: Art as a space for thought. On Aby Warburg's concept of education. Centaurus Verlag, Pfaffenweiler 1997.

- Charlotte Schoell-Glass: Aby Warburg and anti-Semitism. Cultural studies as intellectual politics . Fischer Taschenbuch, Frankfurt am Main 1998, ISBN 3-596-14076-5 .

- Wolfgang Bock: Hidden sky lights. Stars as messianic orientation. Benjamin, Warburg. In: W. Bock: Walter Benjamin. The rescue of the night. Stars, melancholy and messianism. Aisthesis, Bielefeld 2000, pp. 195-218.

- Georges Didi-Huberman : L'image survivante: histoire de l'art et temps des fantômes selon Aby Warburg . Les Éd. de Minuit, Paris 2002, ISBN 2-7073-1772-1 .

- Hans-Michael Schäfer: The cultural studies library Warburg. History and personality of the Warburg Library, taking into account the library landscape and the urban situation of the Free and Hanseatic City of Hamburg at the beginning of the 20th century. Berlin 2003.

- Ludwig Binswanger : Aby Warburg: La guarigione infinita. Storia clinica di Aby Warburg. A cura di Davide Stimilli. Vicenza 2005 (in German: The infinite healing. Aby Warburg's medical history. Diaphanes, Zurich / Berlin 2007).

- Cora Bender, Thomas Hensel, Erhard Schüttpelz (eds.): Snake ritual. The transfer of forms of knowledge from the Hopi Tsu'ti'kive to Aby Warburg's Kreuzlinger lecture. Akademie Verlag, Berlin 2007, ISBN 978-3-05-004203-9 .

- Thomas Hensel: How art history became an image science: Aby Warburg's graphics. Akademie Verlag, Berlin 2011, ISBN 978-3-05-004557-3 .

- Martin Treml, Sabine Flach, Pablo Schneider (Eds.): Warburgs Denkraum. Shapes, motifs, materials. (Trajekte book series). Wilhelm Fink Verlag, Munich 2014, ISBN 978-3-7705-5077-7 .

- Karen Michels: It has to get better! Aby and Max Warburg in dialogue about Hamburg's mental solvency. Hamburg University Press, Hamburg 2015, ISBN 978-3-943423-28-0 .

- the like in full text (PDF)

- Andreas Beyer et al. (Ed.): Picture vehicles. Aby Warburg's legacy and the future of iconology. Wagenbach, Berlin 2018, ISBN 978-3-8031-3675-6 .

- Horst Bredekamp: Aby Warbug, the Indian. Berlin explorations of a liberal ethnology , Wagenbach, Berlin 2019, ISBN 978-3-8031-3685-5 .

- Kurt W. Forster: Aby Warburg's cultural studies. A look into the abyss of the images. Matthes & Seitz, Berlin 2019, ISBN 978-3-95757-242-4 .

America trip

- Claudia Naber: Pompeii in New Mexico. Aby Warburg's American trip. In: Buccaneers. No. 38, 1988, pp. 88-97.

- Benedetta Cestelli Guidi, Nicholas Mann (Eds.): Photographs at the Frontier. Aby Warburg in America, 1895-1896 . Merrell Holberton Publishers in association with the Warburg Institute, London 1998.

- Benedetta Cestelli Guidi, Nicholas Mann (Ed.): Border extensions. Aby Warburg in America 1895-1896 . Dölling and Gallitz, Hamburg 1999.

- Benedetta Cestelli Guidi, Claudia Cieri Via, Pietro Montani (eds.): Lo sguardo di Giano. Aby Warburg tra tempo e memoria . Torino 2004.

Italy trip

- Karen Michels (Ed.): Aby Warburg. With Bing in Rome, Naples, Capri and Italy. Karen Michels on the trail of an unusual journey . CORSO, Hamburg 2010, ISBN 978-3-86260-002-1 .

Mnemosyne

- Martin Warnke (Ed.): Aby Warburg. The Mnemosyne picture atlas. 2nd Edition. Berlin 2003.

- Marianne Schuller: Representation of the unthought. On the constellative procedure in Aby Warburg's Mnemosyne Atlas. In: Modern Language Notes. Vol. 126, No. 3, 2011 (German Issue), pp. 581-589.

- Georges Didi-Huberman : Atlas or the Anxious Gay Science. In: Atlas. How to Carry the World on One's Back. Exhibition catalog Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofia Madrid, 2010, ISBN 978-84-8026-429-7 , pp. 14-220.

- Christopher D. Johnson, Claudia Wedepohl (Eds.): Mnemosyne: Meanderings Through Aby Warburg's Atlas , Cornell University Library & The Warburg Institute 2013ff (online).

- Aby Warburg: L'Atlas mnémosyne: avec un essai de Roland Recht. L'écarquillé-INHA, 2015, ISBN 978-2-9540134-3-5 . (French)

Essays

- Peter Gorsen : On the problem of archetypes in art history. Carl Gustav Jung and Aby Warburg. In: Kunstforum international . Volume 127/1994, pp. 238-249.

- Andreas Beyer: What connected Franz Marc and Wassily Kandinsky with Aby Warburg, in Ulf Küster (ed.): Kandinsky Marc & Der Blaue Reiter, exhibition catalog Fondation Beyeler, Riehen / Basel 2016, Hatje Cantz Verlag Berlin 2016, pp. 18–23. ISBN 978-3-7757-4168-2

Web links

- Literature by and about Aby Warburg in the catalog of the German National Library

- arthistoricum.net: Digitized works in the "History of Art History" portal

- Manfred Bauschulte: "Jew by birth, Hamburger at heart, in the Florentine spirit". In: deutschlandfunk.de , April 19, 2015.

- Matthias Bruhn : educ.fc.ul.pt: Enciclopédia e Hipertexto. Aby Warburg. The survival of an idea.

- engramma.it: Aby Warburg: Introduction. Picture atlas. Mnemosyne. 1929. ( E-journal that has published a lot about Warburg)

- sas.ac.uk: Warburg Library London

- Philippe-Alain Michaud: trivium.revues.org: Zwischenreich. Mnemosyne or the subjectless expressivity. ( Trivium. Journal for the humanities and social sciences. # 1, 2008; about Warburg's art project, last accessed on April 19, 2015)

- Warburg House: Abi Warburg ; warburg-haus.de (Hamburg)

- Leibniz Center for Literary and Cultural Research Berlin, information on an edition project on Aby Warburg: zfl.gwz-berlin.de

- Manfred Bauschulte: "Jew by birth, Hamburger at heart, in the Florentine spirit". In: deutschlandfunk.de , Long Night , 11./12. June 2016.

- Archive of the Aby Warburg Foundation

Individual evidence

- ^ Ernst H. Gombrich: Aby Warburg. New edition. Hamburg 2006.

- ↑ Gombrich 2006, p. 118.

- ^ A Lecture on Serpent Ritual. In: Journal of the Warburg Institute. 2 (1939) London, pp. 277-292; the German version (based on a German version of the lecture created by Gertrud Bing and Fritz Saxl)

- ↑ Gombrich 2006, p. 131.

- ^ Warburg: Pagan-ancient prophecy in words and pictures in Luther's time. Quoted from: Warburg: Selected Writings and Appreciations. 1980, p. 221.

- ^ Warburg: Italian art and international astrology in the Palazzo Schifanoja in Ferrara. 1912/22, p. 1.

- ↑ Warburg 1920. Quoted from Warburg 1980, p. 216.

- ^ Karl Königseder : Aby Warburg in Bellevue. In: Robert Galitz, Brita Reimers (ed.): Aby M. Warburg: "Ecstatic nymph ... mourning river god", portrait of a scholar . Series of publications by the Hamburg Cultural Foundation, Volume 2, Hamburg 1995, pp. 74-103.

- ↑ Ludwig Binswanger, Aby Warburg: La guarigione infinita. Storia clinica di Aby Warburg. A cura di Davide Stimilli. Vicenza 2005.

- ^ Media Art Network: Aby M. Warburg “Mnemosyne Atlas” , as of April 15, 2011.

- ↑ Gombrich 2006, p. 375.

- ^ Carl Georg Heise: Aby M. Warburg as a teacher. 1966.

- ^ Aby Warburg: Collected writings. Dept. 2. Volume 1. Berlin 2003. S. VII.

- ^ Fritz Saxl: The history of the library Aby Warburg (1886-1944). In: Aby M. Warburg. Selected writings and Appreciations. Baden-Baden 1980, p. 335.

- ↑ Architect: Gerhard Lange Maack, Saxl, S. 343rd

- ^ History of the Warburg Institute.

- ^ Doris Bachmann-Medick : Cultural Turns. Reinbek b. Hamburg 2006.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Warburg, Aby |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Warburg, Aby Moritz |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | German art historian and cultural scientist |

| DATE OF BIRTH | June 13, 1866 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Hamburg |

| DATE OF DEATH | October 26, 1929 |

| Place of death | Hamburg |