Noble society

Noble societies were oath- sealed cooperative associations of nobles that developed in the Holy Roman Empire during the transition from the Middle Ages to the early modern period .

The aristocratic societies usually gave each other joint statutes in which their internal and external relationships were regulated. Disputes were settled by arbitration. The " journeymen " strengthened their community through a common festival culture, which could range from common meals to the organization of elaborate tournaments. Common badges or the wearing of uniform clothing at their regular get-togethers helped create a noble identity and demarcation from the outside world. The self-designation that the journeymen found for this type of community was "knighthood".

While at the beginning of the unions political motives (supporting a party in power struggles, protection against expansionist efforts of powerful neighbors) were in the foreground, over time the societies developed into a representative stage for the purpose of living out a noble culture in accordance with rank, also for lower nobility genders, independently from the royal courts. This function was carried out by the pure tournament companies, while the political role was primarily taken over by the company with Sankt Jörgenschild .

The aristocratic societies formed the common identity from which the constituted imperial knighthood could be formed in the 16th century . This could fall back on the infrastructure created by the noble societies.

Delimitation and classification of the term "aristocratic society"

Noble societies as a peculiarity of the Holy Roman Empire

In Anglo-Saxon literature, Boulton developed a system of Western European aristocratic associations. He roughly differentiates between “ true orders ”, which were initiated by a monarch or prince, and “ pseudo orders ”, in which the initiative to merge came from the members, but who nevertheless, with or without an oath , subordinate to a sponsor.

When trying to use this system for the creation of a repertory for the classification of the German aristocratic societies, Kruse, Paravicini and Ranft Boultons found the classification impractical because it did not do justice to the "... colorful and changeable character ..." of the societies they observed. They describe the Society of St. Antonius (Kleve) as dazzling, for example , which was a prayer fraternity , a court order and sponsor of the Antonite order and finally a rifle brotherhood . They describe the falcon as changeable , which has evolved from an association oriented towards political goals into a tournament society, or the dragon , which has changed from a court order to a badge of honor . They suspect that such cooperative associations were particularly common in Germany in the late Middle Ages, compared to other regions of Europe, because there was no central state geared towards a single monarch. They identify 92 companies that have similarities in terms of their structure (oath, statutes, cooperative organization ...). In view of the meager tradition, they assume that they have captured only a fraction of the actual societies.

In contrast to the kings of England , France or Spain , the Roman-German king did not have a society of his own. The societies in which German kings can be found were societies of their ancestral rulers. The dragon was Hungarian , the eagle Austrian , and “Tusin” Bohemian . The German emperors and kings pursued a flexible policy in the area of tension between emperor / king-prince-nobility-cities, ranging from the general ban on noble societies in the Golden Bull of Charles IV. 1356, through selective bans, to the approval and promotion by King Sigmund in 1422 / 1431 was enough. Friedrich III. pursued opportunistic policies that included both prohibition and promotion. His son Maximilian ran an active sponsorship to promote a counterweight against the princes loyal to the king / emperor.

Differentiation from the term "order"

Many of the names used for individual noble societies are not contemporary. This also applies to the generic terms. Only St. Antonius , Pelikan and St. Hubertus actually called themselves orders. “ Swan Order ”, on the other hand, is a name used in the 19th century - originally the association was called “Society of our dear women”. The same was true of the Dragon Order , which was not named in the deed of foundation and was later referred to as the society with the trakchen , the societas Draconis or the society of the (lind) worm .

Differentiation from the term "tournament society"

The term “tournament society” is also too narrow for a general term. This designation goes back to the occupation with tournament and coat of arms books in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Based on the entries found there, an attempt was made to record membership directories of tournament societies. Since the knowledge of the heralds who created such tournament and coat of arms books was limited and often influenced by regional preferences or, as is clear in the case of Rüxner , also represented subsequent constructions, such compilations are arbitrary. Each "... list adds new names, omitting old names." In the repertory compiled by Kruse, Paravicini and Ranft, only 24 of the 92 recorded societies are listed as Tournament companies designated. Especially with the early societies of the 14th century, the classification as tournament society is completely absent. The society of 1361 is referred to in the literature as the tournament society , but was a political association of Upper and Lower Bavarian aristocrats to influence the unstable Duke Meinrad . 1362 was a noble counter-collar, the Wittelsbach I. Ruprecht and Ruprecht II. , Count Palatine of the Rhine, Stephen II. , Duke of Bavaria-Landshut , and John II. Supported against those who Meinrad "... his land and ringing, knights and knechten, steten un märgten, rich and poor have defeated and defected ... ". With Meinrad's death, both society and the counter alliance disappeared.

Other so-called tournament societies also had predominantly political motives. The society of male band changed its name according to its statutes as tournament company, but was used by Wenzel from Wroclaw to secure his succession by his nephew Ludwig II..

The Society with the Griffin was called the tournament society because of its inclusion in later tournament and coat of arms books - at Rüxner even falsely relocated back to a legendary Magdeburg tournament in 938. It was, however, an alliance between Count Johann von Wertheim , Count Gotfrid von Rieneck and other nobles in order to support each other in the event of an attack. They feared being drawn into the conflict between the Archbishop of Mainz and the Count Palatine Ruprecht the Elder . Wertheim and Rieneck were committed to the archbishop in a contract of service.

A shift in focus can also be observed at the two companies, Falke in Oberschwaben and Fisch am Bodensee . Both societies had participated in tournaments from the start, but especially with the Falcons the internal and external imperative of peace, with arbitration and mutual protection in the event of external attack, was clearly in the foreground. In 1479 there was an alliance agreement between the two remaining independent societies, which was only sealed by the two kings. The aspect of mutual protection played a prominent role in this alliance. In 1484 the two societies then merged to form the Society of Fish and Hawks . This went hand in hand with the time of the great tournaments in the 80s of the 15th century. The membership rules for the new company took explicitly to the " four-country tournaments " References: should be taken only that, "... so far the same from the Vierlanden dess Turners wu approved e rdt". It is interesting that the company's arbitration was transferred to the courts of competition and arbitration of the tournaments, that is, disputes could also be fought in the tournament and before the local arbitration tribunal and the result was acceptable. Another aspect that explains the stronger focus of this new merged company on the tournament is the simultaneous strengthening of the company with Sankt Jörgenschild . Almost all members of the new society were also represented in the mainly political interests of the fish and falcon society . Other societies that understood themselves exclusively as “Thorner societies”, such as the Leitbracken or the Crowned Ibex , had regulations in their statutes for internal peacekeeping, i.e. a cooperative regulation of feuding.

Differentiation from the term "Ritterbund"

The term " knight " in modern terms such as "knight association" or the even more extensive mix of terms "knight order" must be relativized. No company made the “knighthood”, that is, the legitimation through accolade , a prerequisite for admission, in contrast to the “international” medals - the Order of the Garter , the Order of the Golden Fleece or the French Ordre de Saint-Michel . There were "knight societies " like the Fürspang , who called itself "societas militium et militarium", the Roßkamm "societas equestris", or "knight brotherhoods" like St. Hubertus zu Sayn , St. Maria in Geldern and St. Georg zu Friedberg . Here, however, the focus was on the quality of the class and not on the actual knighthood. It is noticeable, however, that the admission criteria of the individual companies have tightened over time. In the course of the territorialization and the associated loss of power of the less powerful aristocrats, their tendencies towards demarcation intensified. In the case of the donkey in 1387 , for example, a simple majority of the class members and freedom from debts was sufficient for admission. In 1430, a new member whose parents were not yet members of the society was not allowed to receive more than four votes against with at least 15 journeymen present. In 1478 this was tightened again. Now only those who could prove the nobility and coats of arms of four ancestors and who had not married unequally were allowed to be admitted . Such aggravations can also be observed among the crowned ibex and the swan society. In the 15th century the fourfold ancestral test becomes more common, for example with St. Hieronymus , St. Christoph , St. Simplicius and St. Martin .

Constituent elements of noble societies

Associations based on fixed rules and customs and organized as cooperatives already existed in other forms, for example guilds and guilds , or among traveling merchants , students and clergy. The important thing - and firmly anchored in medieval thinking - was the importance of form. That means: acts of legal symbolism (for example, oath or common meal), religious exercises (common prayer or mass), regular gatherings and the appointment of common identifying marks.

There are also statutes in the aristocratic societies, in which a name was specified, the duration of the society, whether it was led by one or more captains or so-called kings, where they wanted to meet, which saint was their patron and for what purpose it met, who belonged to the community and how joining and leaving was regulated, what rules and duties the comrades were subject to and what sanctions should apply in the event of violations of these rules. The individual companies differed in their objectives and in the way they lived together and in the details of how all of this was regulated. The current state of knowledge about this is very different; Some companies are only known today through mentions in individual documents, very often in connection with arbitration awards in (from today's perspective) civil law matters. But there were constituent elements that were common to all societies and that made up the special character of societies.

The oath

The main difference between the court orders and the cooperatives lay in the type of oath . In the case of the court orders, it was an oath of homage or allegiance to the lord or the founder and the statutes set by him. In the case of the cooperatives, the emphasis on “we” was in the foreground: “... we the journeymen [name of the company], who are iczunt or who may be afterwards, pledge [...] in good Truwen to Eydestadt to synonymous good journeymen and to keep the company and our eyner to answer for the others […] ”. This formula of the oath was often renewed at the regular meetings and was to be spoken by every new member. By repeating the formula of the oath, the order set by the sworn contract acquired a special meaning. It was a matter of “arbitrary law”, that is, with the will of all those involved, a separate peace and legal system was created, which was secured by its own jurisdiction and, if necessary, defended externally.

The Geselschaff van sent Joeris of July 15, 1375, which was located on the Middle Rhine , Lower Rhine and in the Eifel , had in addition to the general organization (cooperative oath, peace law and internal jurisdiction, chapter, council and captain by election, cash system, uniform skirts) detailed regulations on malice, behavior in war, dealing with prisoners and distribution of spoils of war. The organization and the command structure in the event of a fight were similar to the rules of the tournament societies for the fight between the barriers and were designed for a quick, powerful reaction in a crisis. The founding of the society was based on the preambles of the peace alliances , for the benefit of the country and its people. Not only the own class, but also merchants, farmers and pilgrims, clergy and lay people were taken under protection. So it was a matter of the "presumption" of a public monopoly on the use of force. Therefore, on October 22, 1375, Charles IV had the society forbidden because it was "against God, law, honor and imperial laws". It is noteworthy, however, that it still existed on September 12, 1378 and was accepted at the regional level when it was excluded from the latter as comrades in an alliance between Duke Wilhelm von Jülich and Geldern , Wilhelm von Jülich, Count von Berg and Count Adolf von Kleve has been.

The cooperative oath thus stood in opposition to the land peace regulations with emperors, cities and territorial princes who were becoming more powerful as contractual partners. He questioned the monopoly of force claimed by them to enforce peace in the country. In the peace regulations of the time, societies were therefore often excluded as “bad societies” without specific names. As a counterpart to the societies, the Landfrieden were therefore also endowed with a binding oath, together with the additional requirement that the allies also have to urge their servants and husbands to leave societies if necessary.

In most of the oaths of the societies, the king or emperor was expressly excluded, that is, there was no duty of assistance if it had been directed against the monarch. The own liege lord was also often excluded from the oath.

This led to an ambivalence of the kings and emperors of the Holy Roman Empire towards the aristocratic societies, which was reflected in the prohibitions of such societies on the one hand, and in their active promotion as an instrument of power against the princes on the other. This is discussed in more detail below in the context of the historical classification.

Religious aspect of societies

Not exclusively, but mostly, the societies placed themselves under the patronage of one or more saints. Foundations for the dead or memorials were also often, but not exclusively, part of the agreements. For this purpose, the journeymen met at a fixed spiritual seat. This could be a monastery or a specific church. Often a separate altar or a special side chapel was donated. These were used to hold the death shields . Examples that are still visible today are the Heilig-Geist-Stift in Heidelberg for the pelican and donkey , or the St. Gumpertus Church in Ansbach for the Franconian part of the swan society . Penalties were often attached to the obligation to establish trade fairs .

In the letter of the "Geselschaft vom Aingehürn" it says:

"In the name of God and in the Ern Marie, Mother of God, our dear Frawen, and all dear saints and umb common Frides, Schuczs and Schirms unnser and ours and sunders, which we have denied and endured and helped the holy Christian faith against the Keczer and unglawbigen, who are called the Hussen. "

The religious engagement was not limited to the fight against the Hussites ; extensive entanglements with vigils and 24 soul masses for each deceased journeyman were laid down in the statutes and testify to a lived piety. The journeymen assured each other a mutual solidarity that went beyond death.

There were associations that understood themselves as brotherhood and society at the same time, such as brotherhood and knightly society [...] to praise [...] especially sente Huprichcz . The statutes clearly separated the fraternity and the cooperative part. The brotherhood part dealt with the Christian cult celebrated in the Premonstratensian monastery Sayn , the cooperative part related to the already known functions, such as organization, internal and external peacekeeping. The Counts of Sayn had as part of a four committee the right to propose the king of the society were, but otherwise under the journeyman equal among equals. Society thus represented a prestige and power factor for the Count's House. But the journeymen also benefited from the special reputation and mutual protection in the event of a conflict, both outside and within society. In a religious sense, the splendid ceremony and the outstanding setting of the monastery were felt to be particularly beneficial. Through the foundation of masses and vigils as well as the appointment, accommodation and care of 20 additional priests for the annual Hubertus Mass , the society acted as a sponsor of the monastery.

The Geselscap van den Rade expressed her special piety by not honoring her patron saint, Saint George, as a brilliant dragon slayer, but with the symbol of his martyrdom.

The choice of name also expressed the special demand for a "pure" life in the company of the horned horns and the junkh women . The Virgin Mary as patroness is preceded by the symbolizing unicorn as a symbol of virgin purity, but also of a contemplative way of life that picks up on temptation . The statues stipulated that the journeymen should prevent each other from doing dishonest things and doing business . The statutes were introduced with the requirement to have a high mass sung on the Fourth of our Women's Day . Each of the journeymen should have 30 masses read for a deceased member .

Sociability as part of social life

As a rule, the statutes provided for an annual court day. Most of the time, the chapter meetings took place, with deliberations on new admissions, renewal of the oath of society and other social issues. If necessary, the statutes were adjusted. Then at least one meal was celebrated together, and a tournament was often held at the larger societies. The journeymen were encouraged to bring a predetermined number of women to these days, sometimes with the specific requirement that they should be of marriageable age. Some societies, like the dragon or the swan , admitted women to society.

The feeling of togetherness was expressed in most cases by wearing a shared badge. Wearing uniform clothing also created a feeling of togetherness. Just as the princes made their followers appear in uniform colors for representative purposes at their festivals, so the societies did the same in this regard, in order to also demonstrate their unity to the outside world. The badge was often depicted on the epitaphs and was intended to remind the journeymen that the community in the sense of the medieval memorial system was designed for eternity. The funeral ceremonies were therefore also concluded with a common meal.

Solidarity among the comrades was also exercised by the fact that disputes were to be settled before a joint arbitration tribunal. In addition, fellowship among the comrades was fostered in other ways. The sickle had agreements that the comrades had to lend one of their own to those of them who could not afford their own battle horse or tournament horse. In other societies, too, there were regulations on how to support impoverished comrades through no fault of their own. In times when the economic situation of some aristocrats tempted them to enrich themselves at the expense of others, even their peers, this, in combination with the internal peace obligation, was an important regulatory element.

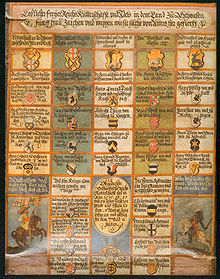

Item of the society servant of the donkey

A persefantt / called Hans Ingeram has made dyz puoch Inn dem / Jar do man Zalt after xpi (Christi) geburd Mcccclviiij (1459) Jar uf / michaelis /

The society offered the lower nobility the opportunity to document their claim to status to the outside world. In contrast to the princes, the nobleman had no opportunities to represent himself at his castle. Since the claim to a leadership role in society was never given up, a new aristocratic platform had to be created to present this claim. This was possible as a common social achievement. The last highlight of this class representation was the four-country tournaments of the last quarter of the 15th century. The city formed the outer framework for such a presentation.

Another form of self-portrayal was the diverse coat of arms and tournament books . The nobles could see themselves as part of a broad community. The tournament books, in particular, established an - often fictional - historical tradition that was supposed to prove the standards of families going back a long way. In his famous tournament book , Georg Rüxner set up a series of 36 tournaments that went back to an imaginary tournament in Magdeburg in 938. For example, these books can be used as more or less reliable sources about the membership of families in aristocratic societies for contemporary conditions, but their statements about the past are to be regarded as fiction. The companies also maintained their own Persevanten that such records first names, such as Hans Ingeram for the company with the donkey .

Social classification of the aristocratic societies

In the late Middle Ages, the lower nobility began to lose their traditional role as rulers, which they had held as the owner of the power of violence on site and as a monopoly of superior weapons technology. It was therefore becoming increasingly unnecessary for the up-and-coming territorial lords and was therefore looking for new forms of security. He did this - wherever possible - in the form of egalitarian oath associations. One explanation for the recruitment potential of such associations is that initially lower nobility, mostly from Swabia, who had hired themselves as condottieri in Italy , formed societies when they returned in the sixties of the 14th century. A few noble societies existed before that, and the cooperative principle was a generally recognized form of organization.

Some princes founded societies to integrate their local nobility. Although these societies were organized as a cooperative in relation to the journeymen, they were more like the hierarchically oriented knight and court orders in their common orientation towards a prince. The princely societies were usually designed to be permanent, while the cooperative associations of the lower nobility were mostly closed for a limited period of time. With extensions, however, these could also last for a very long time. While in the 14th century warlike, short-term alliances based on political opportunity prevailed among the lower nobility, in the 15th century the focus was on social professional representation in longer-term associations.

Number and size of the companies

The number of company foundations rose sharply towards the end of the 14th century. It fell sharply after the first decade of the 15th century and reached another peak around 1440. A final high point was then in the nineties of the 15th century. This was the time of the great "four-country tournaments". The wave of foundations broke off at the beginning of the 16th century. The societies largely disappeared and the lower nobility constituted themselves in the Free Imperial Knighthood.

There were societies that never had more than four comrades ( unicorn and virgin ) or, like the parakeet, represented a union of four princes. It is precisely this association of princes that makes it clear how much the cooperative idea had prevailed in non-hierarchical associations. Others, like the Löwengesellschaft or St. Jörgenschild had 120 and almost 200 members, respectively.

A special application of the cooperative unification principle was found within the Burggrafschaft Friedberg at Friedberg Castle . Here, the cooperative principle was used for the internal organization of a clearly defined group tied to a fixed location: the heirs of the castle. Initially, around 1367, the Green Minne Society came together there, and is known about it through altar donations. In 1384 another society was formed, the Society of Mane (Moon). Both societies merged and went into a brotherhood in 1387. A hundred years later the Burgmannen united before August 26, 1492 to form the Fraternitas equestris S. Georgii . The journeymen met regularly on the Monday after Corpus Christi in the castle chapel for masses and vigils for the deceased. In the chapter meeting that followed, organizational matters relating to the inheritance were also settled.

Geographical distribution

The geographical spread of the societies reflects the cultural differences and the constitutional reality of the empire. In the rest of Western European countries, the modern territorial state developed through the elimination or appropriation of regional forces as a union of kings. In the empire it was the powerful territorial princes who pushed ahead with such a work of unification in a limited space. The process began much later, however, and actually only came to an end with the end of the Holy Roman Empire. Where such territorial princes could not assert themselves, niches arose for an independent policy of less powerful powers. The city federations established themselves here, but also the aristocratic societies considered here.

There, where there were firmly established sovereigns, there are therefore few or no aristocratic societies, but there are many where the independence of the nobility could assert itself in the “sparse zones of public authority”. They were almost completely absent in the north and east (with the exception of leopards from 1387 and lizard society from 1397 ).

Central Germany - Westphalia, Braunschweig-Lüneburg, Saxony, Meißen, Silesia, Austrian states and Bavaria - represented a transition zone in which some aristocratic societies could be found.

They occurred more frequently along the Rhine (Upper, Middle and Lower Rhine) and especially in Swabia and Franconia.

In the area of today's Switzerland, where the cooperative unification took place on a different level, they were completely absent. The local nobility initially found themselves in the Swabian aristocratic societies, later they relocated their center of life either north of Lake Constance and the Rhine or he joined the Swiss Confederation .

The early 14th century societies

The historical development and the geographical distribution of the noble societies reflects the constitutional history of the Holy Roman Empire at that time. The first high point of the foundation coincided with the dispute over the crown of the empire between the houses of Habsburg , Wittelsbach and Luxembourg . The kings Ludwig the Bavarian , Frederick the Fair and Charles IV pursued an intensive domestic power policy , the princes and emerging territorial states also tried to position themselves in these disputes and the lower nobility and the cities had to assert themselves in this network through a clever alliance policy. In addition, the Western schism was instrumentalized in this power struggle. The antipope Clement VII played an important role in this .

An example of this phase was the older society with the Lewen of October 17, 1379. Based on the Counts of Nassau and the Counts of Katzenelnbogen , they were recruited from supporters of the antipope Clement VII. Based on a union of 17 counts, lords and clergymen In the Wetterau , the company soon expanded across the entire south-west of Germany and, from spring 1389, had to be divided into six sub-companies, Lorraine, Franconia, the Netherlands, Swabia, Alsace and Breisgau. In the vicinity of the Counts of Helfenstein , another independent company was established with sant Wilhalmen , which literally took over the statutes of the lions and allied with them on March 1, 1381. On March 8, 1381 the society with Sankt Wilhelm merged with the Franconian society with Sant Gyren .

In response, the South German Association of Cities was founded . Extensive fighting broke out until the peace of Ehingen was concluded on April 9, 1382 through the mediation of Duke Leopold of Austria.

Unique to this constellation was the planned expansion and the establishment of a functioning structure of sub-societies. For example, in the course of the misdirection, it was possible to operate freely in the area of the "subsidiaries".

The noble societies between prohibition and promotion

The power game king – prince – city – lower nobility is also evident in the prohibition / legitimation booms. In 1356, in Article 15 of the Golden Bull, Emperor Charles IV prohibited both city alliances and aristocratic societies. In 1372 he specifically banned the crown . In 1395 King Wenceslas banned the " Schlegler ". Sigismund, on the other hand, legitimized the societies in 1422 and 1431 and tried to integrate them into his peace policy. Friedrich III. In 1467, with explicit reference to the Golden Bull, the unicorn confirmed by Sigismund in 1431 was forbidden , but he and his successor Maximilian were very active in integrating the St. Jörgenschild into their imperial reform policy. The swan society was even legitimized by the Pope, analogous to the well-known Western European court orders.

The noble societies in the 15th century

The high point of the supraregional societies and also their longest lived was the Sankt Jörgenschild . The society was constituted on September 11, 1406 as an association in the Lake Constance area and in southern Swabia to avoid the many legal disputes among themselves. The society was only closed for a limited period of time, but with the appropriate renewals it lasted until the imperial knighthood was established in the 1640s.

As early as the first federal letters in 1407 and 1408, the defense against the rebellious Appenzeller was mentioned as a reason for unification. The society received the consent of the king and church to conclude the covenant. The success in this dispute led to the establishment of further sub-companies with identical federal letters.

The arbitral tribunal, led by the captains, from 1463 onwards by a council, gained increasing, also external, authority, so that it was also called upon by non-members. As early as March 14, 1426, the society received the privilege of admitting private and governor people and the place of jurisdiction for poor people. This privileged court of arbitration was confirmed again in the Golden Bull of 1431. From this period the principle was in the Federal Letter: "... because (ß) they must remain as members of the holy kingdom, St. George, the Church, the kingdom and their lands to honor and strengthen, for use, for peace and room" . From such statements it was concluded, for example by Roth von Schreckenstein , that the consciousness of a free imperial knighthood was developing here.

As early as 1422, the Society was granted the privilege of free choice of alliances by King Sigismund, which was granted by Friedrich III. was confirmed after his coronation in 1440. That is why the company with Sankt Jörgenschild also entered into various alliances with other societies and cities. When the Swabian Federation was founded in 1488, the organizational structure of the company was used to a large extent. The lower aristocrats were represented by society and were members of the federal government. This construction allowed the lower nobility to negotiate on an equal footing with the other estates, especially the princes. The company did not merge with the Swabian Federation, but continued to exist beyond its end.

The company with Sankt Jörgenschild represented a turning point in the late medieval peace policy. From this point on, other companies were also increasingly accepted as partners in peace alliances. Knowledge of some of these societies exists only through their mention in such peace alliances, such as the society with the male dog in the Upper Rhine area between Säckingen and Rastatt . On the other hand, the limits for these societies also become apparent in the areas in which there was a strong connection to a prince. The freedom of action for the rural nobility was becoming more and more limited. But the sovereigns also tried in some cases to instrumentalize the societies for their own purposes, according to Duke Friedrich of Austria , who tied the society with Sant Georgen and Sant Wilhelm's shield in his fight against the confederates.

The limited possibilities of the lower nobility integrated into a state rule to secure their class interests with the help of a society are also clear with the society of vom Aingehürn (April 23, 1428). These aristocrats from the Straubinger Land , the Bavarian Forest and the Upper Palatinate united to defend themselves against the Hussites . To enforce their own rights they allied themselves in 1430 with the Franconian knighthood and with the society with Sankt Jörgenschild , i.e. the imperial-free knighthood. In the time of the succession turmoil in the Wittelsbach house, the nobility's hope of breaking away from the princes seemed to be confirmed. It was not until 1466, on October 16, that the society was renewed. Duke Albrecht expanded his position in Bavaria at this time. When his brother Christoph , who disputed Albrecht's position, was accepted into the society - against protest from his own ranks - Albrecht stoked resistance against society with the support of Ludwig von Bayern-Landshut and the Count Palatine Friedrich and Otto . One year later, on October 19, 1467, the company was officially banned. The society dissolved, the federal letter was cut up and the seals returned to the journeymen. The conflict was not yet over and continued in the so-called Böckler War . The establishment of the Society of the Leon was such an attempt to hold on to self-government organized as a cooperative against the princes' efforts to mediate .

One of the reasons for the end of societies was the Reformation. Brotherhood piety, the ritual tied to fixed places of worship and altars, increasingly collided with the individual religious decisions of the comrades. Even if Protestant comrades wanted to continue to participate in the social network of a fraternal community, the celebrations of Mass were no longer a suitable means for them. Also, Catholic bishops soon stopped accepting Protestant patron saints for altar and church foundations. Conversely, catholic mass celebrations in churches that had become Protestant were unthinkable. Another reason was that the exclusivity claim of some companies could no longer be upheld. The ancestral test that has become stricter and the material expenditure (armor, competition horse, contributions, court keeping ...) could no longer be carried out by many aristocrats or were no longer accepted. An aging population set in. Political demands could now be enforced better in other alliances that were less elitist. With the establishment of the Reich Chamber Court , lawyers were more in demand than warriors. But as with the denominational aspect, this was also a longer-term process.

The relationship between aristocratic societies and cities

In most cases, the relationship between the nobility and cities is portrayed as one-sidedly conflictual. Feuds provoked by the nobles under pretense serve as an example and the image of the robber baron is conjured up. Noble societies, which represented a concentration of military power, were seen as a threat by the cities, which themselves pursued extensive security policies for their trade routes. From the point of view of both the cities and the nobles, this threat came from the princes to the same extent. The city alliances were not directed unilaterally against the nobility, as a rule changing alliances were found, so that the cities also resorted to mercenary troops , which in turn were led by nobles. Or they even took entire companies in their wages, such as the company with the crown for the city of Augsburg, the company with the sword for Ulm, or the Schlegler , who were paid for the cities of Worms and Speyer .

In addition, the central role that the city played for societies must not be overlooked. The city represented the "stage" for the "rulership theater" of the social life of the cooperatively organized aristocracy. The castles of the aristocrats were rarely suitable for this, on the one hand for reasons of space, on the other hand because the castles were usually no more than narrow, represented filthy, walled farms. It would also have contradicted the egalitarian principle if the comrades who had a representative aristocratic seat had thereby been singled out from their peers.

The city was the founding place and secular seat of the societies that used the city's infrastructure for their interests: the scribes who wrote their letters, the archive in which these letters were deposited, the treasury that managed the company's assets, the meeting rooms , where chapter meetings and feasts were celebrated, the places where their tournaments could be held. Above all, only one city offered the possibility of accommodating a large number of people - in addition to the journeymen themselves, their wives and daughters and the servants - as well as looking after them for several days. The gathering in a town also offered the opportunity to stock up on essentials, be it armor, horses, clothing, jewelry or spices. The annual chapter meetings were often coordinated with the city's trade fair dates.

The Martinsvögel met exclusively in Strasbourg to clarify internal disputes and, in particular, money and interest issues , the Fürspänger in Schweinfurt , the Löwler in Cham , and the company with Sant Gyren in Crailsheim . Requests for help to the comrades were also to be sent there, which suggests that the city chancellery was active for the company all year round. This also shows why it could be of interest to a city to be a chapter seat of a society. This gave her a useful informational advantage. The Ayngehürn Society therefore met in Amberg in addition to Regensburg so as not to be dependent on a law firm. The company with Sankt Jörgenschild set up the office of its own scribe from 1433 onwards. There are also several meeting places at supraregional societies. The above-mentioned Sankt Jörgenschild had more than a dozen such meeting places, including Augsburg , Ehingen , Engen , Konstanz , Meersburg , Pfullendorf , Riedlingen and Stockach . The journeyman donkeys met as an upper and lower society in Heidelberg and Frankfurt am Main . The lion society met in Wiesbaden and St. Goar . Other societies left the meeting place open. The Fisch und Falke Society stipulated that its chapter should be held together with the annual court of the “Four Country Tournaments”, the first of which had taken place in Würzburg in 1479.

The only exception were the societies at Friedberg Castle. There, the purpose of these societies - the organization of coexistence on this Ganerbeburg - would not have made a different chapter location appear sensible.

Some cities have thus become host to more than one society. As various city accounts show, the city's representatives made a not inconsiderable effort in honor of their guests: a festive reception at the town hall or at another prestigious place in the city, joint meals, wine gifts, and the provision of city servants. There were solid economic interests behind this, as the cities benefited in many ways from visits by the companies. The hostels, the food suppliers, the handicrafts (cloth makers and tailors, shoemakers, painters, carpenters, saddlers, harness makers ), dealers for luxury goods, horse dealers and other service providers, from notaries to musicians, and many more, often earned several thousand from the visit Participants. At the tournament in Heidelberg in 1482 3,499 horses had to be accommodated, in the same year 4,200 horses in Nuremberg. Another advantage of being the chapter seat of a society was that these were events that could be planned and recurring annually.

In addition to the economic aspect, such events also offered a corresponding entertainment value for all layers of a city. If the city represented a stage on which the nobles could present themselves, this stage was a shop window for the urban patriciate in which they could learn the courtly way of life. The frequent urban journeyman's joys - as the city tournaments were called - show that the townspeople tried to copy the courtly splendor, and in many cases even to surpass it. In order to preserve exclusivity, the nobility only had the option to isolate themselves from the estate, as the aforementioned tightening of the admission rules to the societies for the wedding of the tournament shows.

rating

Andreas Ranft states that the individual companies, apart from the company with Sanktjörgenschild , could hardly exert any formative and lasting influence on their surroundings. The societies were mostly dissolved, neutralized or instrumentalized for their own purposes by a rule or by counter-alliances. But new cooperatives were always emerging. The "... pressure of constantly growing connections ..." prevented a fundamental liquidation. "[T] he noble cooperative became a stable factor of political organization, which allowed the nobles, at least the imperial direct, for a long time an advantageously unexplained competition of multiple loyalties to their feudal lords, to the employers, to their unions and to the empire". Since the privilege of 1422, which allowed the nobility to organize co-operatives, the societies represented a power bloc for the kings or emperors, which they could use as a political counterweight in their disputes with the princes. By - literally - own constant practice of administrative and organizational forms as the role of the nobility in the later imperial knights was prepared. The Swabian Federation as a corporate association allowed the princes and cities to accept the lower nobility as a proper negotiating partner. The trick was that the negotiating partner was not the individual lower nobility, but society. Organizationally, a line can therefore be drawn from the political integration of the Sankt Jörgenschild as a cooperation in the Swabian Federation to the corporate organization of the imperial knighthood in the middle of the 16th century. The knight cantons were based on the canton structure of the Sankt Jörgenschild, but the symbols of other societies were also passed on.

literature

- Holger Kruse, Werner Paravicini , Andreas Ranft (eds.): Order of knights and noble societies in late medieval Germany (= Kiel work pieces. Series D: Contributions to the European history of the late Middle Ages. Volume 1). Peter Lang, Frankfurt am Main 1991, ISBN 3-631-43635-1 .

- Andreas Ranft: Noble societies: group formation and cooperative society in the late medieval empire (= Kiel historical studies. Volume 38). Thorbecke, Sigmaringen 1994, ISBN 3-7995-5938-8 (also habilitation thesis, University of Kiel).

- Tanja Storn-Jaschkowitz: Articles of Association of noble oaths in the late Middle Ages. Edition and typology . Logos, Berlin 2007, ISBN 978-3-8325-1486-0 (also: dissertation, University of Kiel).

- Peter Jezler, Peter Niederhäuser, Elke Jezler (eds.): Knight tournament. History of a festival culture. Book accompanying the exhibition in the Museum zu Allerheiligen Schaffhausen, Quaternio Verlag, Lucerne 2014, ISBN 978-3-905924-23-7 .

Web links

Register of noble societies

The societies listed in the repertory of Kruse, Paravicini and Ranft are indicated twice in the article text, by italics and "quotation marks". This serves to distinguish between mere alliances or hierarchical orders.

- Note: You can jump back to the relevant text passage using the reference marker «↑».

| Surname | Date limitation | founding | region | purpose | Patronage | reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Red sleeves | before June 11th | 1331 | Middle Rhine / Eifel | political / military | ||

| Ettal Knight Abbey | 17th August | 1332 | Ettal Abbey | |||

| Tempelaise / St. George | before June 8th | 1337 | Austria | St. George | ||

| wheel | before January 26th | 1342 | Lower Rhine? | fraternal | St. George | |

| Yellow horses | before April 13th | 1349 | Lower Rhine | political / military | ||

| Tournament company with Hz. Meinhard v. Upper Bavaria-Tyrol | September 28th | 1361 | Upper Bavaria | Tournament society as a cover for political / military goals | ||

| Green love | before September 12th | 1365 | Friedberg Castle | |||

| Wolves | March | 1367 | Swabia | political / military | ||

| pike | March | 1367 | Swabia | |||

| Martinsvögel | 1367 | Black Forest / Baden / Alsace | political / military | |||

| Blue hats | before November 5th | 1367 | on the left bank of the Rhine? | |||

| sword | before September 18th | 1370 | Swabia | political / military | ||

| star | August 23 | 1370 | Freiburg in Breisgau | political / military | ||

| moon | before June 10th | 1371 | Friedberg Castle | |||

| Crown | 6th January ? | 1372 | Swabia | political / military | ||

| star | February 16 | 1372 | Hesse | political / military | ||

| Old love | approx. | 1375 | Hesse | |||

| St. George | 15th of July | 1375 | Middle Rhine / Lower Rhine / Eifel | political / military | St. George, Maria | |

| horn | before January 19th | 1379 | Hesse | political / military | ||

| Gripping | October 2nd | 1379 | Wertheim (around) | political / military | ||

| lion | October 17th | 1379 | Wetterau, then all of southwest Germany | political / military | St. George | |

| Hawks | approx. | 1385-1390 | Westphalia / Paderborn | political / military | ||

| St. Wilhelm | 21st December | 1380 | Swabia | political / military | St. Wilhelm | |

| St. George | before March 8th | 1381 | Francs? | political / military | St. George | |

| Dude / fool | November 12th | 1381 | fraternal | |||

| salamander | before July 9th | 1386 | Habsburg lands | princely | ||

| Pants / boots | before November 4th | 1386 | Meissen | Tournament company, later also military | ||

| Aries | before November 4th | 1386 | ? | Tournament society | ||

| ass | in front | 1387 | Pfalz / Kraichgau / Wetterau | Tournament society | St. Georg, Maria, St. Christoph, St. Katharina | |

| leopard | 1387 | Magdeburg (around) | Tournament company, later also military | |||

| Society of Schweinfurt | September 23rd | 1387 | Lower Franconia | Tournament company, later also military | ||

| sickle | 25th of September | 1391 | Braunschweig / Braunschweig-Lüneburg / Paderborn / Hesse | political / military | ||

| Kid / flail / club / piston | September 29th | 1391 | Hesse | political / military | ||

| Fürspang | approx. | 1392 | Francs | Tournament society | St. Georg, Maria, St. Eucharius, St. Jakob, St. Leonhard | |

| foxes | before July 13th | 1392 | Thuringia? | |||

| Rosskamm | approx. | 1393 | Kleve / Lower Rhine | princely | ||

| Rosaries | May 24th | 1393 | Lower Rhine | Peace alliance | ||

| Braid | in front | 1395 | Habsburg lands | courtly affectionate service | ||

| Schlegel | in front | 1395 | Swabia | political / military | ||

| lizard | February 24th | 1397 | Rheden and Thorn (um) | political / military | ||

| unicorn | before May 30th | 1398 | Thuringia? | |||

| sickle | around | 1400 | Saxony-Anhalt | princely | ||

| deer | or earlier | 1404 | Frankfurt / Main (around) | Tournament society | ||

| star | before January 31st | 1406 | Austria i. e. S. | political / military | ||

| elephant | August 23 | 1406 | Tyrol | political / military | ||

| St. Jörgenschild | September 11 | 1406 | Swabia | political / military | St. George | |

| Falcon | or earlier | 1407 | Swabia (Upper) | Tournament company, with military options | ||

| lion | approx. | 1407 | Thuringia | political / military | ||

| Flail | approx | 1407/1411 | Thuringia | princely | ||

| deer | approx. | 1408 | Regensburg (around) | Tournament society | ||

| Male | approx. | 1408 | Regensburg (around) | Tournament society, 1417 also politically / militarily | ||

| Dragon | 12th of December | 1408 | Hungary (originally, then all of Europe) | princely | ||

| lynx | before January 17th | 1410 | Hessen? | |||

| Male band | in front | 1389 | Silesia, Upper Lusatia, Bohemia, Franconia, Swabia, Bavaria | Tournament society, political / military | Maria? | |

| parakeet | 17th April | 1414 | Bavaria | Princely Society | ||

| St. Anthony | 1420/1435 | Kleve / Mark | fraternal | St. Anthony | ||

| Unicorn and virgin | 17th August | 1424 | Olomouc (Moravia) | fraternal | Maria | |

| Unicorn / Böckler | April 23? | 1428 | Upper Palatinate / Bavaria-Straubing | political / military | ||

| Gripping | or later | 1428 | Regensburg (around) | |||

| Male | before July 24 | 1431 | Upper Rhine? | political / military | ||

| St. Wilhelmsschild | before July 28th | 1432 | Upper Rhine? | Peace alliance | St. Wilhelm | |

| Eagle | March 16 | 1433 | Austria | Combat alliance against the Hussites | Maria | |

| Bracke / Leitbracke | 1436 | Swabia (Lower), Baden | Tournament society | |||

| fish | 1436 | Lake Constance | Tournament society | |||

| Crowned ibex | August 19th | 1436 | Rhineland | Tournament society | ||

| St. George and St. Wilhelm shield | before October 15 | 1436 | Alsace / Sundgau / Breisgau / Black Forest / Thurgau | princely | St. Georg, St. Wilhelm | |

| Tusin | in front | 1438 | Bohemia | Court orders | ||

| rose | before February 21 | 1439 | Bamberg (around) | |||

| Our Lady / Swan | September 29th | 1440 | Mark Brandenburg, then also Franconia | fraternal | Maria | |

| Pelican / St. George | May 20 | 1444 | Rheinpfalz | Court orders | St. George | |

| St. Hubertus | 1444/45 | Jülich-Berg | Court orders | St. Hubertus, Maria | ||

| St. Hubertus | November 11th | 1447 | County of Sayn | fraternal | St. Hubertus, Maria | |

| St. Jerome | 30. September | 1450 | Margraviate of Meissen | fraternal | St. Jerome | |

| Greyhound | in front | 1459 | Middle and Lower Rhine | Tournament society | ||

| wolf | in front | 1459 | Middle and Upper Rhine | Tournament society | ||

| Holy Spirit | 16th September | 1463 | Wasgau / Lower Alsace | political / military | Holy Spirit | |

| St. Christoph | ? | 1465 | County of Henneberg | fraternal | St. Christoph, Maria | |

| Our Lady / St. Maria | June 23 or later | 1468 | Funds | fraternal | Maria | |

| Order of St. George Knights | January 1st | 1469 | Austria | medal | St. George | |

| wreath | in front | 1479 | Upper Swabia | Tournament society | ||

| Bracke and Wreath | in front | 1479 | Swabia | Tournament society | ||

| Crown | in front | 1479 | Swabia | Tournament society | ||

| Fish and falcon | August 23 | 1484 | Swabia | Tournament society | St. George | |

| bear | September 8? | 1484 | Francs | Tournament society | ||

| unicorn | September 8? | 1484 | Francs | Tournament society | ||

| lion | July 14th | 1489 | Lower Bavaria / Upper Palatinate | political / military | ||

| St. Simplicius | January 9th | 1492 | Archbishopric Fulda | fraternal | St. Simplicius, St. Bonifatius, St. Faustinus | |

| St. George | before March 26th | 1492 | Friedberg Castle | fraternal | St. George | |

| St. George | 17th of September | 1493 | Austria | fraternal combat alliance | St. George | |

| St. Martin | 10th of April | 1496 | Archdiocese of Mainz | fraternal | St. Martin, Maria | |

| St. George | November 12th | 1503 | rich | fraternal combat alliance | St. George | |

| St. Christoph | June 22 | 1517 | Styria | singular | St. Christoph |

Notes and individual references

Holger Kruse, Werner Paravicini, Andreas Ranft (eds.): Orders of knights and noble societies in late medieval Germany. Peter Lang, Frankfurt am Main 1991, ISBN 3-631-43635-1 .

- ↑ a b p. 23.

- ↑ a b p. 24.

- ↑ P. 60 ff., Quoted: M. von Freyberg : History of the Bavarian Landstands , Volume I., Sulzbach 1828 and O. Eberbach : The German Imperial Knighthood in its constitutional and political development from its beginnings to 1495 : Contributions to cultural history of the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, Vol. 11, Berlin 1913, reprint Hildesheim 1974.

- ↑ p. 61.

- ↑ p. 21.

- ↑ p. 133.

- ↑ p. 308.

- ↑ p. 334.

- ↑ p. 389.

- ↑ p. 402.

- ↑ p. 455.

- ↑ p. 468.

- ↑ No. 18.

- ↑ p. 314.

- ↑ p. 147.

- ↑ a b c p. 26.

- ↑ p. 111, refers to: Vienna, HHStA, Allgemeine Urkundenreihe.

- ↑ p. 117.

Andreas Ranft: Noble societies: group formation and cooperative society in the late medieval empire (= Kiel historical studies. Volume 38). Thorbecke, Sigmaringen 1994, ISBN 3-7995-5938-8 .

- ↑ a b p. 21.

- ↑ p. 230.

- ↑ p. 185.

- ↑ p. 33.

- ↑ p. 189 f.

- ↑ p. 192.

- ↑ p. 191 ff.

- ↑ p. 22.

- ↑ P. 31 here the founding document of the “Society of the Crowned Ibex” from August 1436, StA Koblenz, inventory 3, no. 145.

- ↑ p. 31, quoted: W. Ebel: Die Willkür. A study on the forms of thought of the earlier German law, Göttinger Rechtswissenschaftliche Studien 6, Göttingen 1953.

- ↑ p. 31.

- ↑ p. 203 refers to the land peace of Emperor Charles IV of 1371 for Franconia and Bavaria.

- ↑ p. 204.

- ↑ p. 215, quoted: W. Altmann (arr.), 1896/97 and 1897–1900: Regesta. Imperii XI. The documents of Emperor Sigmund 1410–1437, I / 2 (1897), no. 8739, Innsbruck.

- ↑ p. 224.

- ↑ p. 225 f.

- ↑ p. 226.

- ↑ p. 221 with an example of the “lizard society” .

- ↑ p. 245.

- ↑ P. 25 quoted K. Ruser: On the history of the societies of lords, knights and servants in southern Germany during the 14th century . In: Journal for Württemberg State History . tape 34/35 , 1975, pp. 1-100 .

- ↑ p. 28 ff., Graphic p. 259.

- ↑ p. 228 ff.

- ↑ p. 25.

- ↑ p. 209.

- ↑ p. 210.

-

↑ p. 213, quoted: Roth von Schreckenstein: History of the former free imperial knighthood in Swabia, Franconia and on the Rhine river, edited from sources .

First volume: The emergence of the free imperial knighthood up to 1437 , volume 1. Laupp, Tübingen, 1859, p. 641. - ↑ p. 214.

- ↑ p. 216, refers to: Germanisches Nationalmuseum, Nuremberg, document book no. 65, fol. 189 ff.

- ↑ p. 216, refers to: J. Chmel: Regesta chronologico-diplomatica Friderici IV., 1938 (Rg. Friedrich IV. Romanorum Regis), Vienna 1838, No. 5220.

- ↑ p. 254 f.

- ↑ a b p. 233.

- ↑ p. 238.

- ↑ p. 240.

- ↑ p. 241.

- ↑ p. 218.

- ↑ p. 218f., Cited: Volker Press: Kaiser Karl V., King Ferdinand and the emergence of the Imperial Knighthood, Wiesbaden, 1980, p. 18.

Others

- ↑ see for example the use of the term knighthood in the Zimmerische Chronik .

-

^ D'Arcy Johnathan Dacre Boulton: The Knights of the Crown. The Monarchical Orders of Knighthood in Later Medieval Europe, 1325-1520 . Woodbridge 1987. , pp. XVII - XXI

Boulton's classification:

"true orders"

- "Monarchical": " Order of the Garter ", " Golden Fleece "

- "Confraternal": swan , St. Hubertus

- "Fraternal": "Black Swan" ( Savoy ), "Tiercelet" ( Poitou ), "Pomme d'Or" ( Auvergne ), "Lévrier" ( Barrois ).

- “Votive” (temporary associations based on a vow): “Ecu Vert à la Dame Blanche” (Boucicaut), “ Fer de Prisonnier ”, ( Bourbon ), “Dragon” ( Foix ).

- ↑ King is a common equivalent term for the elected captains of the societies.

- ↑ As one the Holy imposed torture was wheeled viewed.

- ↑ February 2nd: Candlemas of the Virgin ; March 25th: Annunciation ; August 15th: Assumption and September 8th: Birth of the Virgin .

- ^ Karl-Heinz Spieß: Princes and Courts in the Middle Ages; Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt, 2008, ISBN 978-3-89678-642-5 , p. 92.

- ↑ see the description of life in a castle by Ulrich von Hutten . Printed here: Arno Borst: Lebensformen im Mittelalter. Frankfurt M. [u. a.], 1973, pp. 173-175, text here .

- ↑ see the following chapter .

- ↑ see here and here .

- ^ Day of the archiepiscopal confirmation of the society.

- ↑ This name, which is confusing today, means the area between the Main, Rhine and Lahn.

- ↑ A popular means of securing income was hiring out as a warlord or councilor at courts outside of one's own fiefdom.

- ↑ only four members: Georg Landgraf zu Leuchtenberg and Graf zu Hals, Georg von Sternberg, Georg von Puchberg, Rudolf von Tiernstein. What brought these four together in Ölmütz is not known.