Apsley Cherry-Garrard

Apsley George Benet Cherry-Garrard (born January 2, 1886 in Bedford , Bedfordshire , † May 18, 1959 in London ) was a British polar explorer who participated in the Terra Nova Expedition (1910-1913) under Robert Falcon Scott to Antarctica participated. During this research trip he was involved in the winter march to Cape Crozier and a member of one of several support groups that enabled Scott and four companions to advance to the geographic South Pole . Cherry-Garrard was also a member of the search team that found the last camp of the South Pole Group with the deceased Scott, Wilson and Bowers in November 1912 . He described the expedition experiences in the book The Worst Journey in the World , published in 1922 , which is now one of the classics of travel and polar literature.

After a medical research trip to China in 1914 and his military service in the First World War , Cherry-Garrard discovered serious health problems in 1916, which were probably caused by the traumatic experiences during the Terra Nova expedition and among which he spent the rest of his life The life he spent as a privateer suffered.

Origin and youth

Apsley Cherry-Garrard was born at number 15 on Landsdowne Road in the southern English city of Bedford. His parents were Major General Apsley Cherry (later Cherry-Garrard, 1832-1907), Companion of the Order of the Bath (CB) and Justice of Peace (JP), and his wife Evelyn Edith ( née Sharpin, 1857-1946). Apsley Cherry-Garrard was their oldest child and only son along with five daughters. Originally from France, the Cherry family belonged to the wealthy Victorian middle class. Cherry-Garrard's father had served as an officer in the British Army in the Indian Uprising of 1857 and in the South African Cape Colony in the Border War of 1877 and the Zulu War of 1879.

Apsley Cherry-Garrard spent his youth on the Denford Park family estate in Kintbury, Berkshire and, from 1892, on the Lamer Park estate in Wheathampstead, Hertfordshire . The latter had belonged to the paternal line of the Garrards since the mid-16th century and was inherited by Cherry-Garrard's father. This also gave his father the coat of arms and the name of the Garrards.

At the age of seven years he sent his parents to Grange Preparatory School in Folkestone in the county of Kent . He later attended Winchester College and graduated from Christ Church College , Oxford with a Bachelor of Arts (BA) in Classical Philology and Modern History . Cherry-Garrard, who suffered from severe nearsightedness throughout his life , was considered a shy loner during his school days, who was avoided by his sporty, ambitious classmates. During his student days he developed into an excellent rower and in 1908 he won the prestigious Grand Challenge Cup in Henley-on-Thames in a team at his university in the rowing eight .

Terra Nova Expedition

Cherry-Garrard had admired his father for his adventurous lifestyle at a young age and was determined to emulate him. For this reason, in 1907 he embarked on a trip around the world on board cargo ships . While in Brisbane , Australia , he learned that Robert Falcon Scott was planning his second Antarctic expedition to be the first to reach the geographic South Pole. When Scott's confidante Edward Wilson was staying at the Scottish country estate of a cousin of Cherry-Garrard's in the fall of 1908, he took the opportunity to apply through Wilson for participation in the research trip. After Scott initially refused him despite Wilson's intercession, Cherry-Garrard agreed to donate £ 1,000 (around £ 105,000 today) to the expedition for free. Scott was so impressed by the gesture that he finally officially recruited him as an assistant zoologist, de facto as Wilson's assistant. Cherry-Garrard and Lawrence Oates , who was responsible for looking after the Manchurian ponies they brought with them , were the only members of the expedition who paid money for their participation. Despite being seasick , he was part of the team that covered the entire journey from Cardiff to Cape Evans on Ross Island between June 15, 1910 and January 4, 1911 with the research vessel Terra Nova .

While initially scientific expedition members in particular reacted mockingly to Cherry-Garrard because of his lack of qualifications, Scott wrote that he was "if at all highly intelligent and immediately helpful" and "another of the nature-loving, reserved, relaxed workers." In base camp, Cherry-Garrard was under entrusted, among other things, with the production of an expedition journal after Scott had instructed him to learn how to use a typewriter before the start of the research trip. As editor of the South Polar Times , Cherry-Garrard was a direct successor to Ernest Shackleton and Louis Bernacchi , who had taken on this role one after the other during Scott's Discovery Expedition (1901-1904). With Lawrence Oates, Henry Bowers , Edward Atkinson and Cecil Meares (1877–1937) he moved into common quarters in the expedition hut. He developed friendly relationships with these men as well as Edward Wilson.

Establishment of the supply depots

On January 24, 1911, the team began, as Cherry-Garrard described it, "in a state of hurry on the verge of panic", with the creation of depots for the planned march to the geographic South Pole. He was part of a group of 13, led by Scott, who that day set off with eight ponies and 29 sled dogs on a march of supplies and equipment to the old quarters of Scott's Discovery Expedition on the Hut Point Peninsula . It was the first of a whole series of marches, at the end of which Cherry-Garrard had covered the longest distance of all expedition participants with the equivalent of 4923 km. The goal of the supply marches was to build the southernmost depot on the Ross Ice Shelf at a geographical latitude of 80 ° S , along with other storage facilities.

The project failed because of bad weather and a soft surface in which the ponies, especially when they weren't wearing snowshoes , sank up to their stomach. On February 17, Scott finally had the so-called One Ton Depot docked at 79 ° 29 ′ S, about 56 km north of the targeted position and about 240 km south of the Hut Point Peninsula. Some of the men, among them Cherry-Garrard, were already suffering from frostbite on their faces. When they returned to base camp in separate teams by the end of February 1911, six of the eight ponies perished from cold and exhaustion. Three out of four horses died when Cherry-Garrards, Bowers' and Tom Creans tried together to lead the animals back over a broken ice surface between the Hut Point Peninsula and Cape Evans.

On March 16, 1911, Cherry-Garrard and seven companions undertook one last depot march on the Ross Ice Shelf before the start of the Antarctic winter under the leadership of the deputy expedition leader Edward Evans . The group got caught in a snowstorm, through which they lost their orientation in the meantime in an area with numerous crevasses and only with difficulty reached the so-called Corner Camp east of White Island . The way back, however, went smoothly, so that the team arrived safely at Hut Point on March 23rd.

Winter march to Cape Crozier

On June 27, 1911, Cherry-Garrard, Henry Bowers and Edward Wilson set out on a march to a colony of these birds on Cape Crozier in the middle of the Antarctic winter, which is the breeding season for emperor penguins , in order to collect penguin eggs that were hatched there. The embryos contained in the eggs were supposed to serve as test material to understand the recapitulation theory put forward by Ernst Haeckel , but which has since been largely refuted , according to which embryogenesis is a shortened repetition of the phylogenesis of an organism. At that time, the emperor penguin was considered a particularly primitive bird, whose embryonic development should provide an indication of the missing link in the evolution of birds and reptiles .

The three men had to pull their two transport sleds with a total weight of around 400 kg in almost constant darkness and at temperatures of down to −60.8 ° C to cover the distance of around 97 km from the expedition hut on Cape Evans to the eastern end the Ross Island . In their frozen clothes, they temporarily moved less than 2 miles a day. Cherry-Garrard noted: “If we were clad in lead, we could move our arms and necks and heads better than now.” In addition, the heavy weight of the sled forced her to roll stages after reaching the Ross Ice Shelf on June 28th: After transport They turned part of their equipment over a certain distance to fetch the other part. On the way there, they experimented with their diet on Scott's behalf in preparation for the upcoming South Pole March. While Wilson and Bowers ate a diet rich in fat or protein , Cherry-Garrard mainly ate high - carbohydrate food in the form of biscuits, which led to persistent hunger and heartburn . According to Edward Wilson's records, Cherry-Garrard also suffered more than his companions from frostbite on his hands, feet and face. After advancing to the east some distance from the southwestern coast of Ross Island, they reached Terror Point ( 77 ° 41 ′ S , 168 ° 13 ′ E ), a near-shore foothill of Mount, on July 9 in thick fog Terror at a distance of around 32 km from their target. They were held up here by a storm for three days. After that, temperatures had risen to as low as −13 ° C. As a result, the skids of the transport sleds slid better, and the men sometimes advanced more than 12 km per day.

On July 15, Cherry-Garrard and his two companions finally saw the so-called Knoll , a striking flank volcano of Mount Terror, the steep eastern flank of which forms Cape Crozier. To do this, the men had first circled Cape MacKay ( 77 ° 42 ′ S , 168 ° 31 ′ E ) and then passed an area with strongly jagged ice ridges. After climbing about 250 meters in altitude on the foothills of the Knoll, Cherry-Garrard, Wilson and Bowers built a makeshift shelter ( 77 ° 31 ′ S , 169 ° 22 ′ E ) made of boulders, snow and a canvas roof for three days . Impressed by the surrounding scenery, Cherry-Garrard wrote: “Behind us Mount Terror, on which we stood, and above all the gray, infinite barrier [Ross Ice Shelf] seemed to cast a spell over you with its cold immensity, diffuse [and ] cumbersome, a hotbed of wind, drift and darkness. God, what a place! "

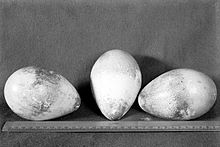

On July 18, Cherry-Garrard, Wilson and Bowers had come within earshot of the colony of emperor penguins after an arduous descent to the ice edge, but had to turn back without having achieved anything after they had reached a dead end in the maze of ice faults on the Cape. The next day they managed to get to a cliff on a steep path and after crawling through a natural ice tunnel, on which about a hundred birds were breeding. Cherry-Garrard wrote exuberantly: “[…] we had material within reach that could prove of the utmost importance to science; we turned theories into facts with every observation we made […] ”. They killed and skinned three of the animals to Tran recovery and collected a five eggs, which they carried in their belts fastened at around the neck fur gloves. On the way back to the camp, which they found with great difficulty in the dark, Cherry-Garrard broke two of the eggs; the remaining three specimens were preserved in alcohol for return transport.

The following days of her stay at Cape Crozier were marked by setbacks. While boiling the penguin skins in their refuge, Wilson was injured in the eye by splashing hot oil. Another storm set in. On the morning of July 22nd, the men discovered that the storm had torn away the tent erected next to the refuge, putting a safe return to Cape Evans in serious danger. Cherry-Garrard noted: “Without a tent we would be dead men.” At noon on July 23rd - Wilson's birthday - the storm tore the canvas roof that served as the roof of their hut, causing the men to be increasingly buried in snow and unable to eat for a day had to spend in their sleeping bags. When the storm subsided for some time on July 24th and they had dismounted a bit from the hill, they found the tent, which was only slightly damaged, and which had caught on a boulder. Dwindling fuel supplies, a broken blubber oven and its battered by the storm shelter did not allow another excursion to the penguin colony.

Cherry-Garrard, Wilson and Bowers left one of the two transport sleds and expendable equipment and started on July 25 on their way back to base camp at Cape Evans. Overtired, struggling against a strong wind and in constant danger of falling into a crevasse in the dark, they made slow progress at first. Cherry-Garrard wrote: "I cannot express in words how helpless [...] we were to help ourselves, and how we found out from a whole series of very horrific experiences." On July 28th, at Terror Point, they were back in the slipstream of Ross Island. The slipstream in turn caused temperatures to drop. According to Cherry-Garrard's records, the lowest value on the way back was −54.4 ° C. His teeth were frozen and were beginning to splinter. On July 31, the three men arrived at the hut at Hut Point, which was not occupied by any of the other expedition members at that time. After a rest of several hours in their tent, which they had set up in the inhospitable hut, they set out on the morning of August 1st for their final stage to the base camp at Cape Evans, which they reached late in the evening of the same day after a total of 36 days of travel. After seeing them, Scott wrote in his diary: “You looked more weathered than anyone I've seen. Their faces were scratched and wrinkled, their eyes cloudy, their hands pale and wrinkled from the constant damp and cold [...] "and" It is obvious that he [Cherry-Garrard] suffered the most - but Wilson tells me that his courage never wavered for a moment. "

South Pole March

Reaching the geographic South Pole for the first time was the main goal of the Terra Nova expedition. Scott and four other expedition members arrived there on January 18, 1912, but about five weeks later than Roald Amundsen and his crew. On the way back to base camp, Scott and his companions died of malnutrition, illness and hypothermia.

preparation

On August 10, 1911, Scott had assigned certain expedition members to look after one of the remaining ten ponies. Cherry-Garrard was responsible for training the gelding Michael for the upcoming South Pole March. Together with Wilson, Oates and Crean, he undertook a final endurance test on October 6th, in which the four men's ponies had to pull heavy loads on transport sleds from Cape Evans to the Hut Point Peninsula.

Away

On November 1, 1911, twelve members of the expedition, including Cherry-Garrard and Scott, set out on the South Pole March with ten ponies and two dog teams. Edward Evans, William Lashly , Bernard Day (1884–1934) and Frederick Hooper (1891–1955) had been traveling south with the two snowmobiles since October 24th . On November 4, Cherry-Garrard, along with Scott and Wilson, came across the first abandoned snowmobile about 16 miles south of the Hut Point Peninsula and only a day later, not far from Corner Camp, the second. After the team arrived at One Ton Depot on November 15, Scott decided, in view of the exhaustion of two ponies, to use all horses as draft animals until they reached Beardmore Glacier and to kill them on the way to care for the dog teams if necessary. Cherry-Garrard took this decision with relief: "[...] the attempt [to lead the horses onto the glacier] would have been an outright suicide." On November 21, they had the group of four around Edward Evans at 80 ° 32 ′ S overtaken. The first pony was shot three days later. The next morning, Day and Hooper were the first support group to head back to base camp. The men advancing further south set up the last depot on the Ross Ice Shelf at 82 ° 47 ′ S on December 1, after three more ponies had been killed. In particular for Edward Evans and William Lashly, who had to pull their own equipment and provisions since the snowmobile failed, the horse meat as food was “like a release” according to Cherry-Garrard. On December 4th, Cherry-Garrard's pony Michael became Caring for the dogs and sacrificed for lack of horse feed. This happened in a camp in the mouth of the Beardmore Glacier in the Ross Ice Shelf. After a storm had kept the men in this camp for four days, Cherry-Garrard pulled one of the transport sleds together with Henry Bowers on the next stage.

After reaching the Beardmore Glacier on December 9th, the remaining five ponies were slaughtered at a camp that Scott then named Shambles Camp (in German: slaughterhouse camp). Given the performance of the dog teams with which Cecil Meares and Dmitri Girew (1888–1932) returned as the next support group on December 11th, Cherry-Garrard came to the conclusion: “It looked like Amundsen was the right one The following ascent over the Beardmore Glacier to the polar plateau no longer had any draft animals available, so that the men had to pull a transport sledge with a weight of up to 400 kg themselves in three groups of four. Cherry-Garrard's group included Tom Crean, Henry Bowers and Patrick Keohane (1879–1950). Progress was made difficult by deep snow and unpredictable crevasses. Cherry-Garrard and numerous other men also suffered from snow blindness. At times, as at the beginning of the winter march to Cape Crozier, they only made progress in rolling stages due to the heavy weight of the sled . On December 17th, after an ascent of about 1100 meters, they reached the Cloudmaker ( 84 ° 17 ′ S , 169 ° 25 ′ E ), a striking mountain on the western edge of the Beardmore Glacier. With that, they had covered about half the distance from the Ross Ice Shelf to the Polar Plateau. The daily distances covered were - after a little more than 3 km at the beginning - now up to 29 km.

Scott had not yet announced which of his remaining eleven companions should accompany him to the Pole. On December 20th, after reaching Buckley Island at the top of Beardmore Glacier, Cherry-Garrard learned that he was not one of them. “That evening was quite a shock. […] Of course I knew what he [Scott] was going to say to me, but I could hardly understand that I should return at the end of the next day. "Cherry-Garrard shared this fate with Edward Atkinson , Patrick Keohane and Charles Wright (1887 -1975).

The paths of the team returning to the north with Cherry-Garrard and the two groups advancing further south parted after the men separated a further 18 km up to a width after a difficult route over strongly fissured ice ridges and numerous crevasses until the evening of December 21 from 85 ° 7 ′ S. On January 3, 1912, the last two groups of four on the polar plateau had reached a latitude of 87 ° 32 ′ S. It was here that Scott announced his decision to make five instead of four, along with Wilson, Oates, Bowers and Edgar Evans, to complete the path to the South Pole, while Crean, Lashly and Edward Evans had to give up their hopes and return to Cape Evans.

way back

On the morning of December 22, 1911, Cherry-Garrard and his three companions set out on the approximately 940 km long way back to the base camp. At the height of the Cloudmaker, Atkinson and Keohane only barely survived several severe falls in crevasses. From the Ross Ice Shelf, the men followed the tracks of the dog teams. Through messages that Cecil Meares and Dmitri Girew had left in the individual depots on the ice shelf, they learned that the teams had made slow progress due to bad weather. Since Scott had the dogs used as draft animals on the way there because of the slower ponies up to a latitude of 83 ° 35 'S, instead of only up to 81 ° 15' S as originally planned, the longer way back had forced both dog handlers to to abuse the food rations for the later groups of returnees. This in turn required Cherry-Garrard and his companions to cut their own daily rations until they reached the One Ton Depot on January 15, 1912, hungry and exhausted. This depot had meanwhile been increased by a joint supply march by Bernard Days, Frederick Hoopers and Thomas Clissold (1886–1963) and Edward Nelson (1883–1923) who were not involved in the South Pole March. Cherry-Garrard, Atkinson, Keohane and Wright subsequently suffered from persistent nausea from eating too quickly . Nevertheless, they reached the hut at Hut Point on January 26th without further incident. There the men learned that the first returnees from the South Pole March (Day and Hooper) had arrived at Cape Evans on December 21, 1911.

Lashly, Crean and Edward Evans, the last of the returning support groups, made their last camp on February 17, 1912 about 50 km south of Hut Point. Evans' health had deteriorated life-threateningly from scurvy on January 27th . Lashly stayed at the camp with Evans, while Crean rushed to Hut Point alone in a two-day forced march for help. Atkinson and Girew set out with the dog teams on February 20 and, with Lashly and Evans, returned to Hut Point two days later.

Supply trip to the One Ton Depot

The dog teams with Meares and Girew had returned from the South Pole March to the Hut Point Peninsula on January 4, 1912. The expedition participants in the base camp were unsettled about Scott's intentions to continue using the dogs. So it remained unclear whether the teams should be spared for later scientific exploratory marches, or whether they should support the returning South Pole group, as Scott had ordered in writing in October 1911. On the other hand, it was certain that there was not enough dog food at the One Ton Depot and that there was no time to move due to the delays due to the late return of the dog teams, the rescue of Edward Evans, the unloading of the Terra Nova that had returned to Ross Island and days of bad weather To implement Scott's order, with the help of the dogs "to meet the group returning home around March 1st [1912] at a latitude of 82 ° or 82 ° 30 ′ south".

Edward Evans' critical health required Edward Atkinson to remain in base camp as the only doctor available. Since Cecil Meares was "recalled because of family matters" was preparing for the journey home with the Terra Nova and Charles Wright, who had offered himself as an alternative to Meares, was supposed to continue the work of the departing meteorologist George Simpson (1878-1965), Cherry finally fell -Garrard is given the task of driving towards the South Pole returnees together with Girew and the dog teams. Cherry-Garrard stated that he had no experience in handling dogs. In addition, he only had poor navigation skills .

Cherry-Garrard and Girew set out south on February 25, 1912. Atkinson had ordered that provisions for both men, the dogs, and the South Pole group be driven to the One Ton Depot as soon as possible. If the South Pole group had not yet arrived there, Cherry-Garrard should decide what to do next. In any case, the return of the South Pole group does not depend on the dog teams; In addition, Scott expressly ordered not to endanger the dogs. Both men reached the depot on March 4th without having met the South Pole group on the way. After replenishing the depot with food, they waited in vain for Scott and his companions until March 10th. Due to the insufficient supply of dog food and bad weather, Cherry-Garrard decided not to go further south but to return to base camp. In addition, the cold caused health problems at Girew. Cherry-Garrard believed the South Pole group was adequately supplied with food. What he did not know was that Scott, Wilson, Bowers and Oates were fighting for their survival about 130 km further south at this point, after Edgar Evans had suffered a brain injury as a result of several falls on February 17th at the foot of Beardmore Glacier Crevasses had died. On March 16, Cherry-Garrard and Girew arrived at Hut Point. According to Atkinson, Cherry-Garrard suffered a physical and mental breakdown upon arrival. Atkinson and Keohane then succeeded without the exhausted dog teams only to undertake a supply march to the Corner Camp until March 30, before bad weather and falling temperatures forced them to turn back. After the two men returned on April 1, Cherry-Garrard noted: “We have to come to terms with it now. The Pole Group will most likely never return. And there is nothing we can do anymore. "

Search for the missing south pole group

On March 4, 1912, nine members of the expedition started their journey home on board the Terra Nova . In return, the new chef Walter Archer (1869–1944) and the seaman Thomas Williamson (1877–1940) arrived as newcomers at Cape Evans. Thus, including Cherry-Garrard, 13 expedition members under the leadership of Edward Atkinson remained for a further year to occupy the base camp in Antarctica.

During the winter months, the team continued the scientific program. She also looked after the sled dogs and the newly arrived mules . Cherry-Garrard resumed his editorial work on the South Polar Times and cataloged the ornithological and other zoological specimens he had collected . The men were faced with the ungrateful task of deciding whether they should clarify the fate of the missing South Pole Group in the upcoming summer or look for a six-person group headed by Victor Campbell (1875-1956), the so-called Northern Group , who had been missing in northern Victoria Land . Cherry-Garrard wrote, “It is impossible to describe and almost impossible to imagine how difficult it was to make this decision.” To his surprise, all members of the expedition voted for another march south with only one abstention. Their efforts suffered a severe setback during the winter when numerous sled dogs perished from heartworm disease .

The search for Scott and his four companions began on October 29, 1912. A group of eight set out on that day, led by Charles Wright, with the seven mules from Cape Evans. Cherry-Garrard, Atkinson and Girew followed with two weakened dog teams on November 1st from Hut Point. On November 11th, both groups reached the One Ton Depot. The mules turned out to be much more robust compared to the ponies in the previous year. After the team had covered about 21 km south the next day, they encountered the last camp of the South Pole group. Cherry-Garrard noted: "We found her - to say it was a horrible day does not describe it - words are not enough here." In the tent were the bodies of Scott, Wilson and Bowers. Scott's diary records indicated that the group had reached the South Pole on January 18, 1912, but a month later than Roald Amundsen and four companions. The search team also learned of Edgar Evans' death and that Lawrence Oates had voluntarily put an end to his life on March 17, about 42 km south of the last camp after leaving the tent in a blizzard because of severe frostbite. After the three remaining men in the South Pole group had emaciated themselves after Oates' death and dragged themselves further north for two more days, a persistent snow storm had prevented further progress to the saving One Ton Depot. Scott's record ended on March 29 with an urgent appeal to care for the bereaved of the dead.

The three dead men were covered with the outer tarpaulin and a high snow hill was built over them, which was flanked by two upright transport sleds and on the top of which was a wooden cross made of ski boards. The search party secured the diary entries, the meteorological log, a few letters, the photographic material and about 15 kilograms of rock samples from the South Pole group. In the subsequent search for Oates' body, the team found only his sleeping bag with a theodolite in it , a Finnesko boot and socks. On November 15, at the approximate position where Oates had left the tent, they erected another hill of snow, which was also crossed and in which Cherry-Garrard and Atkinson left a memorial to Oates, signed by them. When the members of the search party returned to Hut Point on November 25, they found Campbell's note about the safe return of the northern group to base camp. On this occasion, Cherry-Garrard noted: "What a relief and how different things now appear!"

Return to England and follow-up

The Terra Nova arrived at Cape Evans on January 18, 1913 to pick up the expedition members. Between January 20 and 22, the day of departure, a crew of eight erected a wooden memorial cross made by the ship's carpenter on Observation Hill at Hut Point, in which the names of the five dead of the South Pole Group and, at the suggestion of Cherry-Garrard, a quotation Alfred Tennyson's poem Ulysses is engraved: “Strive, seek, find and not give up.” After the ship arrived in Oamaru, New Zealand on February 10, news of the death of Scott and his four companions spread around the world. In the course of this, a discussion broke out immediately about whether Cherry-Garrard and his companion Dmitri Girew were responsible for the sinking of the South Pole group due to failure to provide assistance. The other surviving members of the expedition resolutely countered this accusation in a telegram sent from New Zealand to the Daily Mail .

Some time after Cherry-Garrard had returned to Cardiff from New Zealand on June 14, 1913 on the Terra Nova , he learned of the fate of George Abbotts (1880–1923), a member of the now-lost Northern Group, who returned from the expedition had to seek psychiatric treatment. Abbott was at risk of losing his Royal Navy pension rights because of the illness . Cherry-Garrard prevented this through personal intervention with the British Admiralty. He also made contact with the relatives of those who died during the expedition, including the mothers of Bowers and Oates and Scott's wife Kathleen . Oriana Wilson, the wife of his dead friend Edward Wilson, remained on friendly terms with Cherry-Garrard until her death in 1945.

In the late summer of 1913, Cherry-Garrard delivered the three emperor penguin eggs collected at Cape Crozier to the Natural History Museum in London . The manager of the biological collection was dismissive towards him, reluctantly accepted the eggs and made him wait for hours to receive a receipt. When Cherry-Garrard visited the museum some time later with Scott's sister Grace (1871-1947) and they could not be given any information about the whereabouts of the eggs, Grace Scott threatened to publicize the matter nationwide after an ultimatum of 24 hours and so expand into a scandal. A hasty research by the museum officials revealed that the eggs had been indirectly transferred to the Scottish zoologist James Cossar Ewart of the University of Edinburgh . In his microscopic examinations of the embryos contained in the eggs, Ewart was unable to determine any homology in the embryonic development of the plumage of birds and the scale armor in reptiles, which meant that the hoped-for proof of a common ancestor in the evolution of both animal classes failed to materialize. It was not until 1934 that the University of Glasgow zoologist Charles Wynford Parsons published the results of Ewart's work in a scientific publication with the comment that the emperor penguin eggs brought by Cherry-Garrard “did not contribute very much to understanding the embryology of penguins to have."

Expedition to China

In February 1914, Cherry-Garrard and Edward Atkinson embarked on a medical expedition led by the parasitologist Robert Leiper (1881-1969) from the London School of Tropical Medicine to eastern China. The aim was to research the pathways of infection of the Asian form of schistosomiasis caused by the pair leech Schistosoma japonicum , from which numerous seamen of the British merchant navy fell ill in Chinese waters. Cherry-Garrard, Atkinson and Leiper rented a houseboat , which they converted into a floating laboratory and with which they traveled the Yangtze along the trade routes for tea and silk . The search for a suitable and willing schistosomiasis patient to collect schistosome eggs was unsuccessful, which led to arguments between Atkinson and Leiper. Cherry-Garrard left early. He returned by train via Harbin and after crossing Siberia and central Russia back to England, where he arrived on May 10, 1914.

World War I and Later Life

At the beginning of World War I, Cherry-Garrard volunteered . After brief training in the Aldershot garrison , he was given the rank of Lieutenant Commander on November 9, 1914, in command of an armored car company of the Royal Naval Air Service in support of the troops fighting in Flanders . His unit was probably never directly involved in combat and was transferred back to England after the Second Battle of Ypres in May 1915.

In the spring of 1916 Cherry-Garrard fell ill with ulcerative colitis and was dismissed from military service as an invalid . The illness was accompanied by severe depression , the cause of which, according to current knowledge, was post-traumatic stress disorder as a result of the tragic events during the Terra Nova expedition. The health problems left him bedridden for several years, during which he was repeatedly tormented by the thought of being responsible for the demise of the South Pole Group and especially for the death of his close friends Edward Wilson and Henry Bowers. Writing down the experiences during the expedition in the book The Worst Journey in the World , published in 1922, the title of which Cherry-Garrard was inspired by his neighbor, George Bernard Shaw , also served as a means of psychotherapeutic processing of the trauma suffered . The foreword of the book contains Cherry-Garrard's assessment of the most important protagonists of the Golden Age of Antarctic exploration , which was cited in numerous later books about this period:

"For a joint scientific and geographic organization, give me Scott , […] for a spin to the Pole and nothing else Amundsen , and if I'm in a hellhole and want to get out, give me Shackleton anytime ."

The public attention that Cherry-Garrard received after the book was published led to friendships with the writers HG Wells and Arnold Bennett , the mountaineer George Mallory and with TE Lawrence , who had achieved world fame as Lawrence of Arabia and, on his death, Cherry-Garrard wrote an obituary.

1917 Cherry-Garrard had, despite its progressive health problems, together with the Australian polar explorer Douglas Mawson launched a campaign to life and other celebrities that the killing of the then endangered Crested penguins to Trangewinnung on the Macquarie should stop. His calls for protests in newspapers, including the London Times , finally led in December 1919 to the government of the responsible Australian state of Tasmania first imposing an unlimited moratorium on the protection of animals and finally declaring Macquarie Island a nature reserve in 1933.

In the course of the 1920s, Cherry-Garrard seemed to have made a full recovery, but eventually his depression resurfaced. By him previously operated passionate fox hunting he gave up and he was looking for in the years to distraction by collecting literary first editions and on cruises in the Mediterranean . On September 6, 1939, he married Angela Katherine Turner (1916–2005), 30 years his junior, whom he met during a voyage to Norway. The marriage, which lasted until his death, remained childless. After the end of World War II , his poor health and financial demands from the tax authorities forced him to sell the family property Lamer Park, which was later demolished. For the rest of his life, he shared an apartment with his wife in an apartment building in Westminster .

In November 1948 the world premiere of the British film Scott's Last Ride took place in London . After a request from producer Michael Balcon, Cherry-Garrard refused to allow him to be portrayed in the film. Balcon had cast his role with the actor Barry Letts .

Cherry-Garrard died at the age of 73 on May 18, 1959 during a stay at the London luxury hotel The Berkeley of complications from heart failure . He was buried in the family grave of the Cherry Garrards at the northwest end of St. Helen's Churchyard in Wheathampstead, which is marked with a head-high Celtic cross . In the cemetery church there is a bronze statue made in his image as a polar explorer and a plaque commemorating his life.

aftermath

Cherry-Garrard's book The Worst Journey in the World is one of the classics of travel and polar literature. It has been published by various publishers in multiple editions up to the present day and was translated into German for the first time in 2006 under the title Die Schlimmste Reise der Welt . In the summer of 2001, the English original version led a ranking set up by the National Geographic Society under the title The 100 Best Adventure Books of All Time (German: The 100 best adventure books of all time ). Numerous other reviewers followed this assessment . Peter Matthiessen called it "the best book ever written about Antarctic exploration". Kathrin Passig described the chapter on the winter march contained in the book as “one of the best and most haunting descriptions of the absurd disparity between effort and result [...].” The British polar historian Roland Huntford considered Cherry-Garrad's work to be “an immature but convincing, highly emotional defensive writing. "

Sara Wheeler wrote the first biography in book form about the polar explorer in 2001 under the title Cherry: A Life of Apsley Cherry-Garrard .

In 2007 the BBC produced a biographical docu-drama about Cherry-Garrard with Mark Gatiss in the lead role under the title The Worst Journey in the World . Barry Letts , who played Cherry-Garrard in Scott's Last Ride almost 60 years earlier , is the narrator of the epilogue . In the seven-part British television series The Last Place on Earth from 1985, which is based on Huntford's double biography Scott and Amundsen , Cherry-Garrard was played by Hugh Grant .

In November 2010, the Mayor of Bedford City unveiled a plaque on Cherry-Garrard's birthplace.

Participants of the Commonwealth Trans-Antarctic Expedition (1955-1958) discovered the remains of the refuge built by Cherry-Garrard, Wilson and Bowers during a visit to Cape Crozier. Preservation as a cultural and historical monument , decided by the Secretariat for the Antarctic Treaty , is in the hands of the New Zealand Antarctic Heritage Trust . The equipment that the three men had left behind in 1911 is now being kept in New Zealand museums.

The emperor penguin eggs collected during the winter march to Cape Crozier have been in the possession of the Natural History Museum again since James Cossar Ewart's investigations were completed, where they have since been made available to other zoologists for investigations. Douglas Russell, curator of the museum's scrim collection, said in an interview with The Guardian on January 14, 2012, that of the 300,000 exhibits in the collection, the three pieces contributed by Cherry-Garrard received the most attention.

At an auction by Christie’s auction house on October 9, 2012, 27 letters Cherry-Garrard wrote to his mother during the Terra Nova expedition, had previously been estimated at up to £ 80,000, for a sale of £ 67,250. His silver polar medal and the Scott Memorial Medal, which was also awarded to him by the Royal Geographical Society , were auctioned together for £ 58,000 on June 19, 2013.

After Apsley Cherry-Garrard are in the Antarctic the northern Victoria Land located Mount Cherry-Garrard ( 71 ° 18 ' S , 168 ° 41' O ), consisting of a snow field on Mount Kirkpatrick fed Garrard Glacier ( 84 ° 7 ' S , 169 ° 35 ′ E ) as well as the Cherry Glacier ( 84 ° 30 ′ S , 167 ° 10 ′ E ) and the Cherry Icefall ( 84 ° 27 ′ S , 167 ° 40 ′ E ), which flows into the Beardmore Glacier . He is also named for the marine digeneans belonging flukes of nature Lepidapedon garrardi which is found in Antarctic waters.

literature

- Apsley Cherry-Garrard: The Worst Journey in the World . Constable & Co., London 1922 (English, Vol. I and Vol. II in the Internet Archive [accessed October 27, 2011]).

- German edition: The worst journey in the world , Malik, 2013. ISBN 978-3-492-40468-6

- Edward RGR Evans : South with Scott . The Echo Library, Teddington 2006, ISBN 1-4068-0123-2 (English, limited preview in Google Book Search).

-

Leonard Huxley (Ed.): Scott's Last Expedition . Vol. I. Smith, Elder & Co., London 1914 ( in the Internet Archive [accessed October 26, 2011]).

- Leonard Huxley (Ed.): Scott's Last Expedition . Vol. II. Smith, Elder & Co., London 1914 ( in the Internet Archive [accessed October 26, 2011]).

- Sara Wheeler : Cherry: A Life of Apsley Cherry-Garrard . Modern Library, New York 2003, ISBN 0-375-50328-5 .

Web links

- Literature by and about Apsley Cherry-Garrard in the catalog of the German National Library

- Apsley Cherry-Garrard. Illustrated short biography on coolantarctica.com (English)

- The British Antarctic Expedition 1910–1913. Photo collection of the Terra Nova expedition on the homepage of the Polar Museum at the Scott Polar Research Institute of the University of Cambridge (English)

- Worst journey in the world. Information and video about the winter march to Cape Crozier on the website of the Natural History Museum (English)

Individual evidence

- ^ A b c David Nash Ford: Apsley Cherry-Garrard (1886–1959) , short biography on berkshirehistory.com (English, accessed December 6, 2012).

- ^ A b Nick Smith: Plaque unveiled for Bedford's forgotten explorer , bedfordshire-news.co.uk of November 19, 2010 (English, accessed December 6, 2012).

- ↑ a b c Mark Pottle: Garrard, Apsley George Benet Cherry- , biographical entry in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (English, accessed December 9, 2012).

- ↑ Nicholas Jenkins: Maj. Gen. Apsley Cherry-Garrard , genealogical information on the Stanford University homepage (accessed December 9, 2012).

- ^ Nicholas Jenkins: Evelyn Edith Sharpin , genealogical information on the Stanford University homepage (accessed December 9, 2012).

- ↑ a b c d Adam Jones-Lloyd: Apsley Cherry-Garrard , short biography on hertsmemories.org.uk from October 6, 2011 (English, accessed December 10, 2012).

- ↑ Denford Park ( Memento of October 4, 2013 in the Internet Archive ), information about the property on the homepage of the Hungerford Virtual Museum (English, accessed on January 22, 2013).

- ↑ London Gazette . No. 26333, HMSO, London, October 11, 1892, p. 5679 ( PDF , accessed November 12, 2012, English).

- ↑ a b Janna McGuigan: Forgotten Adventurer - A Life of Apsley Cherry-Garrard ( Memento of February 8, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF; 89 kB), short biography from 2002 on nzaht.org (English, accessed on 6. December 2012).

- ↑ Wheeler: Cherry: A Life of Apsley Cherry-Garrard , 2003, pp. 30-31.

- ↑ Cherry-Garrard: The Worst Journey in the World, Vol. I , 1922, pp. Xlvii.

- ↑ Calculation using a template: inflation

- ^ Huxley: Scott's Last Expedition, Vol. I , 1914, p. 611.

- ↑ Cherry-Garrard: The Worst Journey in the World, Vol. I , 1922, pp. 1-86.

- ^ Huxley: Scott's Last Expedition, Vol. I , 1914, p. 183: “ if anything the most intelligently and readily helpful. ”

- ^ Huxley: Scott's Last Expedition, Vol. I , 1914, p. 263: “ Another of the open-air, self-effacing, quiet workers. ”

- ^ Wheeler: Cherry: A Life of Apsley Cherry-Garrard , 2003, p. 61.

- ^ South Polar Times , illustration and information on the expedition magazine on the homepage of the Ten Pound Island Book Company (English, accessed on January 22, 2013).

- ^ Huxley: Scott's Last Expedition, Vol. I , 1914, p. 124.

- ↑ Cherry-Garrard: The Worst Journey in the World, Vol. I , 1922, p. 104: “ in a state of hurry bordering on panic. ”

- ↑ Huxley: Scott's Last Expedition, Vol. I , 1914, 139-143.

- ^ Wheeler: Cherry: A Life of Apsley Cherry-Garrard , 2003, p. 448: 3059 miles .

- ↑ Cherry-Garrard: The Worst Journey in the World, Vol. I , 1922, p. 116.

- ^ Huxley: Scott's Last Expedition, Vol. I , 1914, p. 173.

- ↑ Cherry-Garrard: The Worst Journey in the World, Vol. I , 1922, pp. 127 and 136-154.

- ↑ Cherry-Garrard: The Worst Journey in the World, Vol. I , 1922, p. 166.

- ^ Huxley: Scott's Last Expedition, Vol. I , 1914, p. 211.

- ↑ Cherry-Garrard: The Worst Journey in the World, Vol. I , 1922, p. 234.

- ↑ Cherry-Garrard: The Worst Journey in the World, Vol. I , 1922, pp. 230-231: 757 lbs .

- ↑ Cherry-Garrard: The Worst Journey in the World, Vol. I , 1922, p 248: -77.5 ° F .

- ↑ Cherry-Garrard: The Worst Journey in the World, Vol. I , 1922, p. 254: “ If we had been dressed in lead we should have been able to move our arms and necks and heads more easily than we could now. ”

- ↑ Cherry-Garrard: The Worst Journey in the World, Vol. I , 1922, p. 240.

- ↑ Cherry-Garrard: The Worst Journey in the World, Vol. I , 1922, pp. 257-258.

- ^ Huxley: Scott's last Expedition, Vol. II , 1914, p. 22.

- ↑ Cherry-Garrard: The Worst Journey in the World, Vol. I , 1922, p. 253.

- ↑ Cherry-Garrard: The Worst Journey in the World, Vol. I , 1922, p. 256: 9 ° F.

- ↑ Cherry-Garrard: The Worst Journey in the World, Vol. I , 1922, p. 260.

- ^ Huxley: Scott's last Expedition, Vol. II , 1914, p. 29.

- ↑ Cherry-Garrard: The Worst Journey in the World, Vol. I , 1922, p. 262: “ Behind us Mount Terror on wich we stood, an over all the gray limitless Barrier seemed to cast a spell of immensity, vague, ponderous , a breeding-place of wind, drift and darkness. God! What a place! ”

- ↑ Cherry-Garrard: The Worst Journey in the World, Vol. I , 1922, p. 268: “ […] we had within our grasp material which might prove of the utmost importance to science; we were turning theories into facts with every observation we made […] ”.

- ↑ Cherry-Garrard: The Worst Journey in the World, Vol. I , 1922, p. 272.

- ↑ Cherry-Garrard: The Worst Journey in the World, Vol. I , 1922, p. 270.

- ^ Huxley: Scott's last Expedition, Vol. II , 1914, p. 45.

- ↑ Cherry-Garrard: The Worst Journey in the World, Vol. I , 1922, p. 280: “ Without a tent we were dead men. ”.

- ^ Huxley: Scott's last Expedition, Vol. II , 1914, pp. 49-51.

- ↑ Huxley: Scott's last Expedition, Vol. II , 1914, pp. 61-62: “ I cannot put down in writing how helpless I believe we were to help ourselves, and how we were brought out of a very terrible series of experiences. ”

- ↑ Cherry-Garrard: The Worst Journey in the World, Vol. I , 1922, p. 291: −66 ° F.

- ↑ Cherry-Garrard: The Worst Journey in the World, Vol. I , 1922, p. 292.

- ^ Huxley: Scott's last Expedition, Vol. II , 1914, p. 71.

- ^ Huxley: Scott's last Expedition, Vol. I , 1914, p. 361: “ They looked more weather-worn than anyone I have yet seen. Their faces were scarred and wrinkled, their eyes dull, their hands whitened and creased with the constant exposure to damp and cold […]. ”

- ^ Huxley: Scott's last Expedition, Vol. I , 1914, p. 362: “ It is evident that he has suffered most severley - but Wilson tells me that his spirit nevere wavered for a moment. ”

- ↑ Cherry-Garrard: The Worst Journey in the World, Vol. II , 1922, p. 350.

- ^ Huxley: Scott's last Expedition Vol. I , 1914, p. 376 .

- ^ Huxley: Scott's last Expedition Vol. I , 1914, p. 422 .

- ↑ Cherry-Garrard: The Worst Journey in the World Vol. II , 1922, p. 321 .

- ↑ Cherry-Garrard: The Worst Journey in the World Vol. II , 1922, pp. 327-328.

- ↑ Cherry-Garrard: The Worst Journey in the World Vol. II , 1922, p. 328: “ […] the attempt was suicidal. ”

- ↑ Cherry-Garrard: The Worst Journey in the World Vol. II , 1922, p. 335.

- ↑ Cherry-Garrard: The Worst Journey in the World Vol. II , 1922, p. 340: “ came as a relief. ”

- ↑ Cherry-Garrard: The Worst Journey in the World Vol. II , 1922, pp. 343-344.

- ^ Huxley: Scott's Last Expedition, Vol. I , 1914, pp. 492-493.

- ↑ Cherry-Garrard: The Worst Journey in the World Vol. II , 1922, p. 351: “ It began to look as if Amundsen had chosen the right form of transport. ”

- ↑ Cherry-Garrard: The Worst Journey in the World Vol. II , 1922, p. 354: 800 lbs.

- ^ Huxley: Scott's Last Expedition, Vol. I , 1914, p. 494.

- ↑ Cherry-Garrard: The Worst Journey in the World Vol. II , 1922, p. 353 and p. 355.

- ^ The Cloudmaker , entry on geographic.org (accessed January 8, 2013).

- ↑ Cherry-Garrard: The Worst Journey in the World Vol. II , 1922, p. 352.

- ↑ Cherry-Garrard: The Worst Journey in the World Vol. II , 1922, p. 362.

- ↑ Cherry-Garrard: The Worst Journey in the World Vol. II , 1922, p. 362: “ This evening has been a rather shock. […] Of course I knew what he was going to say, but could hardly grasp that I was going back - to tomorrow night. ”

- ^ Huxley: Scotts Last Expedition, Vol. I , 1914, pp. 528-529.

- ↑ a b Cherry-Garrard: The Worst Journey in the World Vol. II , 1922, p. 383.

- ↑ Cherry-Garrard: The Worst Journey in the World Vol. II , 1922, pp. 401-407.

- ↑ Cherry-Gerard: The Worst Journey in the World, Vol. II , 1922, pp. 410-413.

- ^ Evans: South with Scott , 2006, p. 89.

- ↑ Karen May: Could Captain Scott have been saved? Revisiting Scott's last expedition. Polar Record. First view article, October 2012, p. 9: “ meeting the returning party about March 1 in Latitude 82 or 82.30 ” (accessed November 27, 2012).

- ↑ Cherry-Garrard: The Worst Journey in the World Vol. II , 1922, p. 429: “ recalled by family affairs ”

- ↑ Cherry-Garrard: The Worst Journey in the World Vol. II , 1922, p. 415.

- ↑ Cherry-Garrard: The Worst Journey in the World Vol. II , 1922, p. 417.

- ↑ Cherry-Garrard: The Worst Journey in the World Vol. II , 1922, p. 416.

- ^ Huxley: Scott's Last Expedition Vol. II , 1914, p. 298.

- ↑ Cherry-Garrard: The Worst Journey in the World Vol. II , 1922, p. 420.

- ^ Huxley: Scott's Last Expedition Vol. I , 1914, p. 632 (distance table).

- ^ Huxley: Scott's last Expedition Vol. II , 1914, p. 308.

- ↑ Cherry-Garrard: The Worst Journey in the World Vol. II , 1922, p. 427: “ We have got to face it now. The Pole party will not in all propability ever get back. And there is no more that we can do. ”

- ↑ Cherry-Garrard: The Worst Journey in the World Vol. II , 1922, p. 436.

- ^ Huxley: Scotts Last Expedition, Vol. II , 1914, p. 318.

- ↑ Cherry-Garrard: The Worst Journey in the World Vol. II , 1922, pp. 441-443.

- ↑ Cherry-Garrard: The Worst Journey in the World Vol. II , 1922, p. 443: “ It is impossible to express and almost impossible to imagine how difficult it was to make this decision. ”

- ↑ Cherry-Garrard: The Worst Journey in the World Vol. II , 1922, p. 453.

- ↑ Cherry-Garrard: The Worst Journey in the World Vol. II , 1922, p. 480: “ We have found them - to say it has been a ghastly day, cannot express it - it is too bad for words. ”

- ^ Huxley: Scott's Last Expedition, Vol. I , 1914, p. 595.

- ^ Huxley: Scott's Last Expedition, Vol. II , 1914, pp. 346-347.

- ↑ Cherry-Garrard: The Worst Journey in the World Vol. II , 1922, pp. 482-484.

- ↑ Cherry-Garrard: The Worst Journey in the World Vol. II , 1922, p. 493: “ What a relief it was and how different things seem now! ”

- ^ Huxley: Scott's Last Expedition, Vol. II , 1914, pp. 398-399: " To strive, to seek, to find, and not to yield. ”

- ↑ [No name]: Evans denies hidden secret about Scott. Article from the online archive of the New York Times dated February 17, 1913 (accessed January 17, 2013).

- ^ Wheeler: Cherry: A Life of Apsley Cherry-Garrard , 2003, p. 166.

- ^ Wheeler: Cherry: A Life of Apsley Cherry-Garrard , 2003, pp. 158-159.

- ^ Wheeler: Cherry: A Life of Apsley Cherry-Garrard , 2003, p. 160.

- ↑ Cherry-Garrard: The Worst Journey in the World Vol. I , 1922, pp. 299-301.

- ↑ Cherry-Garrard: The Worst Journey in the World Vol. I , 1922, Appendix

- ^ CW Parsons: Penguin Embryos, British Antarctic (Terra Nova) Expedition, 1910, Natural History Report. Zoology Vol. 4 (7) , 1934, p. 253: “ not greatly add to our understanding of penguin embryology. ”

- ^ [No name]: Hunt a deadly parasite. Article in the online archives of the New York Times on February 9, 1914 (accessed January 17, 2013).

- ^ Wheeler: Cherry: A Life of Apsley Cherry-Garrard , 2003, pp. 166-168.

- ^ Wheeler: Cherry: A Life of Apsley Cherry-Garrard , 2003, pp. 172-174.

- ^ Wheeler: Cherry: A Life of Apsley Cherry-Garrard , 2003, pp. 177-178.

- ^ Wheeler: Cherry: A Life of Apsley Cherry-Garrard , 2003, pp. 179-180.

- ↑ Tom Parry, Sophie Jackson: Anniversary of the hunt for body of North Pole legend Captain Robert Scott. Article in the online edition of Daily Record magazine on November 17, 2012 (accessed January 16, 2013).

- ↑ Cherry-Garrard, The worst Journey in the World, Vol. I, 1922, pp. Viii: “ For a joint scientific and a geographical piece of organization, give me Scott; [...] for a dash to the pole and nothing else, Amundsen: and if I am in the devil of a hole and want to get out of it, give me Shackleton every time. ”

- ↑ Sale 7261 / Lot 196 , exhibit on the Christie's auction house homepage (English, accessed on January 16, 2013).

- ↑ Wheeler: Cherry: A Life of Apsley Cherry-Garrard , 2003, pp. 195-196 and pp. 210-211.

- ↑ Obituary, The Times, May 19, 1959, p. 13a.

- ↑ Lucy Moore: The nice man cometh . Article in the online edition of The Observer newspaper , November 4, 2001 (accessed January 16, 2013).

- ↑ Nicholas Jenkins: Apsley George Benet Cherry-Garrard , genealogical information on the Stanford University homepage (accessed January 16, 2013).

- ↑ Michael Brooke: Scott of the Antarctic (1948). Review of the film on the British Film Institute's website (accessed January 17, 2013).

- ^ Wheeler: Cherry: A Life of Apsley Cherry-Garrard , 2003, p. 298.

- ↑ Apsley George Benet Cherry-Garrard , entry in the Find a Grave database (accessed January 16, 2013).

- ^ Photo of the statue and plaque in St. Helen's Church in Wheathampstead on waymarking.com (accessed June 10, 2013).

- ↑ a b Kathrin Passig : Polar research is not a cookie meal. ( Memento of August 21, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) Review of the German version published by Semele-Verlag in Berlin, Süddeutsche Zeitung in autumn 2006 (accessed on January 16, 2013).

- ↑ Extreme Classics: The 100 Greatest Adventure Books of All Time ( Memento of March 28, 2010 in the Internet Archive ), nationalgeographic.com of May 2004 (English, accessed January 15, 2013).

- ^ The Worst Journey In The World by Apsley Cherry-Garrard ( Memento from October 23, 2015 in the Internet Archive ), collected reviews on vintage-books.co.uk (accessed on January 25, 2013): “ The finest book ever written about Antarctic exploration ”.

- ↑ Roldand Hunt Ford: Race for the South Pole. The Expedition Diaries of Scott and Amundsen , Continuum, London 2010, ISBN 978-1-4411-6982-2 , p. 307: “ an immature but persuasive, highly charged apologia ”.

- ^ The Worst Journey in the World (2007) , entry in the Internet Movie Database (German and English, accessed on January 15, 2013).

- ^ The Last Place on Earth (1985) , entry in the Internet Movie Database (German and English, accessed on January 16, 2013).

- ↑ Management Plan for Antarctic Specially Protected Area No 124. (PDF; 476 kB) Information on the homepage of the Secretariat for the Antarctic Treaty (English, accessed on January 16, 2013).

- ^ Wilson's Stone Igloo , atlasobscura.com (accessed January 16, 2013).

- ^ Robin McKee: How a heroic hunt for penguin eggs became 'the Worst Journey in the world'. Article in The Guardian newspaper online January 14, 2012 (accessed January 15, 2013).

- ↑ Amy Oliver: It has been an absolute hell ': Youngest member of Captain Scott's doomed expedition describes horror of finding explorer's frozen body at South Pole in letters to his mother set to fetch £ 80,000. Article in the online edition of the Daily Mail newspaper , July 19, 2012 (accessed January 15, 2013).

- ↑ http://www.paulfrasercollectibles.com/News/BOOKS-&-MANUSCRIPTS/2012-News-Archive/Harrowing-Captain-Scott-letters-sell-for-$107,800-at-Christie's/12039.page (link not available )

- ↑ Lot 773. Information on the homepage of the auction house Dix Noonan Webb, London (English, accessed June 24, 2013).

- ↑ Mount Cherry-Garrard , entry on geographic.org (accessed January 16, 2013).

- ^ Garrard Glacier , entry on geographic.org (accessed January 16, 2013).

- ↑ Cherry Glacier in the Composite Gazetteer of Antarctica (accessed May 21, 2019).

- ↑ Cherry Icefall , entry on geographic.org (accessed January 16, 2013).

- ^ William C. Campbell, Robin C. Overstreet: Historical Basis of Binomials Assigned to Helminths Collected on Scott's Last Antarctic Expedition. ( Memento from April 29, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF; 1.8 MB) Journal of the Helminthological Society of Washington 61 (1), 1994, pp. 1–11 (English, accessed June 21, 2013).

- ↑ David Gibson, Krzysztof Zdzitowiecki: Lepidapedon garrardi (Leiper & Atkinson, 1914). World Register of Marine Species 2013 (accessed June 21, 2013).

Remarks

- ↑ Full name: Dmitri Semjonowitsch Girew ( Russian : Дмитрий Семёнович Гирев); alternative spellings in various books and sources: Dimitri, Dmitriy or Demitri and Girev, Gerov or Gerof.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Cherry-Garrard, Apsley |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Cherry-Garrard, Apsley George Benet (full name) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | British polar explorer |

| DATE OF BIRTH | January 2, 1886 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Bedford |

| DATE OF DEATH | May 18, 1959 |

| Place of death | London |