Thasos (mining and metal extraction)

Mining and ore smelting on the island of Thasos has a very long and remarkable history. With long-term interruptions, this extends from the Neolithic to the 2nd millennium of our era. Beginning with the extraction of red ocher in the oldest underground mining in Europe, it spread from around the 8th millennium BC. Chr. To Byzantine times continued with the mining and smelting of non-ferrous and precious metal ores and the extraction of marble. In the 20th century AD, the mining of zinc ores, iron ores and marble was resumed, with the extraction of marble alone continuing to this day.

Tectonics and geology

The island represents the southernmost part of the Greek Rhodopes . It is surrounded by large, steep faults and crystalline basin basins several thousand meters deep: the most important Nestos Prinos basin to the north-west of the island, the West Thasos basin to the west and south-west. Apollonia Basin or Orphanos Basin with continuation to the Strymon Basin, as well as the East Thasos Basin east of the island with transition to the Komotini Basin. The crystalline body of the island juts out of these basins at the edge of a clump from 4,000 to 6,000 m below sea level to the surface of the Aegean Sea and further over 1,200 m to the peaks of the Ipsarion massif. The deep basement basins in the Neogene were filled with massive sediment sequences and contain the oil and natural gas deposits that have been in production since 1972 and other as yet underexposed .

On the island of Thasos, the Rhodope series consists of metamorphic crystalline rocks, i.e. mica schists , quartzites , gneiss and coarse crystalline marble . The stratigraphic - petrographic structure of this series is shown in the column chart on the right, based on the status of 1988.

The rich ore mineralization in the basement of the island goes back in most of the deposits to synsedimentary deposits in the Ais-Matis or Kastrou marble series. Syngenetically rising hydrothermal solutions in the fracture and fissure zones of the folds of mountains are responsible for a few but very significant ore deposits . In the surface area, the primary ore minerals were exposed to redistribution, mineral metamorphosis and oxidation as a result of karstification . They are mainly found in crevices and crevices and were extracted in the mines explored so far.

Since early Greek times, but especially in antiquity and up to the Byzantine period, the island's mineral resources formed the basis for its special wealth and importance in the North Aegean: gold, silver, lead, copper and iron were mined and smelted. Zinc ore and iron ore mining took place in modern times, marble extraction from the 10th century BC. Until the present day.

Mining

The non-ferrous metal, silver and iron ore mining took place almost exclusively in the western part of the island, gold mining almost exclusively near the east coast and marble extraction to this day in the eastern half of Thasos.

Red ocher

In the southwest of the island, five kilometers northeast of Limenaria, the German geologist Dr. Herrmann Jung in 1956 in the concession area of the Mavrolakka open-cast iron ore mine owned by Chondrodimos SA, the underground red ocher mines of Tzines . Knowledgeable locals led the archaeologists to two other ocher quarries, those of Vaftochili near Kalivia / Limenaria and those of Boyes near Skala Rachoni. The Greek Antiquities Service, the 18th Ephorie Kavala , started the research 25 years later with the German Mining Museum Bochum and published the first results in 1988. The details have been available since 1995.

The mining area of Tzines has about 20 mining sites on the slopes of the hill of the same name with clear signs of mining of hematite outcrops in Bingen, pits and tunnel mouth holes. After opening the mouth holes, two unbroken tunnels and mining areas were explored.

In the degradation T1 is the largest and most well-studied underground mining, a söhligen , widened tunnel construction, seven meters long, three feet wide and 0.7 to one meter high, and a subsequent short lugs of 1.4 meters in length and a Height from 0.3 to 0.6 meters. Around 500 mining tools such as rubble as striking tools, flint blades, antler shoots and bones of cattle and antelopes as well as bone spades were excavated at the joints in the T1 and T2 mines. The stone age tools have been recorded in detail and captured photographically.

The tool finds, especially the bone finds, have been dated to the second half of the Paleolithic, the Upper Paleolithic (after the 20th millennium BC). Dismantling T1 was carried out over a long period of time with clearly recognizable interruptions. The latest dating is in the Early Neolithic, around 6400 BC. B.C., but mining until the Middle Neolithic is not unlikely. The underground ocher mining on Thasos is therefore much older than the ocher culture, and certainly much older than the oldest known underground mines in Europe, the flint mines of the Copper and Early Bronze Ages. Tzines is therefore the oldest underground mining in Europe .

On the slope above T1 is the underground chamber of the T2 mine, three by four meters wide, one to one and a half meters high and three short tunnel exits. Since almost exclusively stone tools were found here, this mining operation can be assigned to a later, prehistoric period.

The T3 tunnel has broken in the front area. The rear part has not been explored. Stone tools were found in particularly large numbers on the bottom. Only a few stone tools and slates were found at the mouth of tunnel T6 , which is not accessible.

The ancient ocher mining Vaftochili is located 500 meters north of Kalivia / Limenaria. It comprises an extensive tunnel system with a total length of several hundred meters. The dismantling took place until the middle of the last century. This also applies to the surface excavations and the extensive system of tunnels at Boyes .

marble

→ Today's mining: Thasos marble

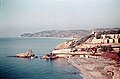

The prehistoric marble extraction was limited to the coastal region of Thasos. The most famous quarries were Fanari, Saliara, Vathi and Pyrgos in the northeast and Aliki and Archangelos in the southeast of the island. Back then, the white dolomitic marble was mined in the Saliara region and the calcitic marble in the Aliki region.

The Pariers showed particular interest in the marble deposits on the island after their settlement. They began in the 7th century BC. With the mining in the summit area of the Acropolis, at Cape Fanari, in Vathi and Aliki, where they could use the experience in the extraction of marble blocks that they had won on Paros. In archaic times Fanari and Vathi continued to operate, and the quarries of Pyrgos and Pholia, Vathi and Saliara were added. In the classical period, mainly Aliki, Thymonia, etc. a. also Fanari and Vathi 3, in the Hellenistic the new mining in Marmaromandra was opened. The extraction in Roman times is proven in Saliara. The marble quarrying flourished particularly during the Byzantine period. In the Middle Ages, the extraction was greatly reduced, in the 14th century new quarries were opened and production rose again.

Thasos marble has only been partially processed on the island since the earliest times, but most of it was exported in blocks. In the late archaic period Macedonia, the Peloponnese, Turkey, southern Italy and the Middle East were supplied. Thasos marble reached all of Italy at the end of the Hellenistic period. In Roman times, Vathi marble was exported in large quantities to distant Mediterranean areas. In the second century Italy was the main market. South Greece, the Aegean Islands, Aegean Turkey, Jordan, Egypt, Tunisia and the Rhone Valley in France were also supplied.

The fine to medium-grained, light white dolomite marble from Vathi was preferably used for the manufacture of statues, portrait busts, heads, grave steles, reliefs, door frames and sarcophagi. The latter went u. a. prefabricated in large numbers by Vathi to Rome. It is believed that most of the dolomite marble sculptures made from ancient times to Roman times were made from Vathi marble.

The most extensive and most important marble quarries were, however, operated in the southeast of the island, especially on the Aliki peninsula , from the seventh century without major interruptions until the Byzantine period. Here an unmistakably coarse-grained and homogeneous calcite marble of high value at that time was extracted.

With the Vathi marble, but especially with the Aliki marble, Thasos became one of the most important marble exporters for ancient Greece: Aliki marble was found in the temple of Pergamon , in the Apollo temple of Didyma , in the mausoleum of Halicarnassus and in the sanctuary of the Kabyren on the island of Samothrace .

During the times of the Roman Empire, Aliki marble was one of the best in the empire. Vitruvius , Seneca , Pliny and Plutarch gave testimony to the fame of the Thai marble, which was found in Ephesus in the fourth century BC. BC, in Thrace and in numerous buildings in Rome.

The current marble quarrying takes place in the same regions that were quarried in prehistoric times, i. i. in the Kastania and Livadakia mountains above the Agios Ioannis bay (type Saliara) and in the area of Theologos (type Aliki). The marble quarrying represents the last and only remaining mining activity on the island. It is of great economic importance for Thasos.

slate

In addition to the marble occurring on the island, the gneiss is the dominant type of rock and the most important local building material. Slate is a fine-grained gneiss with a fine-layered structure and a platy formation. The easy-to-separate panels show an almost flat surface.

Two metamorphic slate series of different mineral compositions can be seen from the stratum profile, the upper Maries series and the lower Kinyra / Potamia series.

The deposits that could be used as slate were only available in a few deposits on Thasos, with limited amounts. The slate quarries, so-called “Plakarias”, were mostly opened up in connection with the construction and maintenance of settlements. The slate quarries “Kalivi Liapi” near Krini / Kinyra, “Moni Karakallou” in the upper Maries valley, “S-chidia” and “Kalami” in the south of the island are known.

Slate was already used in prehistoric times, from the late Copper Age to the early Iron Age. In the grave fields around Kastri, the side walls of the crate graves are made of dry layered slate or slabs placed on edge and covered with large slabs.

In the early settlements in the 4th century, slate was used to cover small stone houses and to pave courtyards and paths. One example of this is the “Tris Kremi” settlement in the Panagia area. In the archaic and classical times, the walls were partly built from slate or banked gneiss.

The slate quarries were operated in early times by knowledgeable Albanians and Epirotians. Slate roofing was created by local artisans until the late 19th century.

volume

With the spatially very limited alluvial coastal plains, the island of Thasos has only small sedimentary clay deposits. These also have very different chemical and physical compositions. This also applies to the gang tones from fault zones. This fact meant that several types of clay had to be used for certain products in the processing plants.

In the archaic studio of Phari , east of Skala Maries, and in the amphora production of Vamvouri Ammoudia in the south of the island, two types of clays were generally used, which differed greatly in their composition for numerous chemical elements. In addition, another quality of clay was used in Phari, but it was used for the production of thick, compact and large ceramic goods.

Lime clays, which were mainly used for black-glazed ceramics in the ancient Greek world, are very rare on Thasos. For the manufacture of high quality utility ceramics, fired at high temperatures, non-calcareous, kaolinitic clays are required, which are also only available in small quantities.

Thasos has considerable deposits of red, non-calcareous, decalcified clays. However, the ancient potters excluded the use of these less plastic clays because they are very rich in iron, which causes cracks in the glaze of the ceramics.

Lead, silver and copper ores

The ancient mining of lead, zinc, silver and copper in the west and south of the island was traced back to the mining activities that started there again at the beginning of the 20th century. In addition, scientific investigations on metal, slag and charcoal finds, as well as ore samples from the old quarries, made it possible to determine the origin of the ores used and to date the mining and smelting.

The lead finds from Tsinganadika , in the southwest of the island, indicate smelting and corresponding early mining that took place in the Late Bronze to Early Iron Ages . The origin of the lead and silver ores has not yet been proven with certainty. However, the use of ores from the nearby mining of Vouves is suspected, possibly also from the mining of Sotiros in the west of the island.

In the early Iron Age (around 800 BC) the mining of lead ores containing silver began in the west and south-west of the island . It finally expanded in a narrow belt about 40 km long from Cape Pachys in the north to Cape Salonikos in the south. In terms of deposit type, lead-zinc-silver ore management is synsedimentary deposit formation in marble. Overprinted by karstification, the zinc was carried away by solutions in the surface area and accumulated there. Lead-rich and low-silver ore batches were formed on and near the surface, which were extracted in tunnels but also in smaller open-cast mines down to a depth of around 15 m. From north to south, the following mines and outcrops are known and have been partially investigated.

Ancient mining was found at Skala Rachoniou in the areas of Agrelea, Spilios, Pachys and Korifi . Five tunnel entrances and a widely ramified route system with clear tool marks and lamp niches were found. An ore layer there contains 37% lead and 100 mg / g silver.

The ore mines in Sotiros from the Early Iron Age are located about 2.5 km inland in the west of the island. The old burrows were largely destroyed by the calamine mining in the 20th century. The silver content of the ores is likely to have been around 280 mg / g. The significant production of silver lead ore in Sotiros may have been roughly equivalent to that of the largest mine in Vouves. In Sotiros, slaves were also employed underground, which is proven by the discovery of a foot skeleton with remains of ankle chains. In ancient times and in Roman times there was insignificant mining of lead, zinc, silver and probably copper ores in Sellas and Agios Elephterios .

In Kallirachi occurrence is Padia in which four shafts and in a cutting three incident studs having a larger excavation chamber could be detected. About 100 tons of lead almei were extracted here. In the lead-silver mining of antiquity, this mining was of little importance. This also applies to Aermola , where an opencast mine cut and tunnel mouth holes date to the Byzantine period around 710. The most important ancient copper mine on Thasos is that of Makrirachi, southeast of Kallirachi. Five tunnels and a 300 m long route system with large expansions were excavated . In addition to copper sulphides, iron-manganese ores, calamine and antimony pale ore were found in this deposit. Vessel finds that are possibly connected with mining point to the 3rd century BC. Chr. Further mining for copper took place in Koumaria (2nd half of the 4th to the beginning of the 3rd century BC and turn to the 2nd century BC), in Koupanada (previously unexplored tunnels and widenings), in Agios Elephterios ( archaic), in Marlou (Byzantine), and on the western slope of the Acropolis Mountain in Limenas Thasou , where Cu-Fe heaps from the 6th century were found. In Aplokada , an ore vein was traced in a few meters of tunnels that contained insignificant copper pyrites.

The ore district of Marlou - Kourlou has an extension of about 3 km and traverses the Ais Mathis mountain ridge from Kallirachi to the Maries valley in a southeastern direction . Both pits are considered to be the best preserved underground lead-silver mining area on Thasos. In Marlou, with over 20 tunnels, tunnel systems, numerous widenings and blind shafts that have been explored to date, construction began in the 4th century BC. Until the 6th century AD, relatively rich lead-silver ores were extracted. The silver content might have been up to 1,510 mg / g, according to J. Speidel up to 6,000 g / t. The Marlou deposit type differs from that of most other ore deposits. The very rich mineralization occurs on a NW-SE fault zone in a vein-like, quartz-bearing rock. In open-cast mines and 3 tunnels with large expansions, chambers and branch lines explored so far, the old mining in Kourlou has remained untouched by more recent activities. A lead gloss sample contained 890 mg / g silver. Further mine workings are suspected.

The lead-zinc mines of Koumaria are about 3 km north of Kalivia / Limenaria on the southern Ais Mathis slope. It is mainly about road constructions with irregular widening. The silver content was around 560 mg / g, the total silver recovery is estimated to be less than 1 ton. An excavation in an ore tunnel near Koumaria yielded ceramic shards and brick fragments from the end of the 4th / beginning of the 3rd century BC. Numerous fragments of large storage vessels were found within the tunnel of this mine, but also fragments of Thai pointed amphorae and small unpainted vessels, which, according to typological criteria, were found between the end of the 3rd and the beginning of the 2nd century BC. Can be dated. The thermoluminescence measurements also give the same values. A destroyed ancient building immediately to the east of the tunnel is found towards the end of the 4th and beginning of the 3rd century BC. Dated.

Several ancient opencast mines, pingen and underground mines in Kokkini Petra , in the Mavrolako district, near the slag heaps of Skres, are believed to have produced lead contents of 9.5% and silver contents of 90 mg / g.

The old tunnels in Vouves , 2 km northeast of Limenaria , some of which can still be seen today in the bumps of the large open-cast mine from 1903 to 1914, are believed to have been around 800 BC. Chr. To about 1000 with a total output of about 150,000 t and lead contents of 1 to 8%, besides about 5000 t of lead, brought some tons of silver. It was not until the Byzantine period that mining in Vouves came to a standstill due to the exhaustion of the lead-silver ores that were then profitable for processing. Julius Speidel describes this mining as the "ancient construction on lead ore" or as mining in antiquity with large cavities and pings on the surface, then underground operations .

Gold / silver ores

Herodotus (484–426 BC) traveled to Thasos and reports on a gold mining operation on Thasos (VI, 47): I have seen these mines myself. By far the strangest of these was the one discovered by the Phoinists who settled with Thasos on this island, which then got its name from this Phoiniker Thasos. This Phoenician mine is located on Thasos between Ainyra and Koinyra, across from Samothrace, where a whole mountain fell over the dump while mining . Herodotus also comments on the annual income of the Thasians from gold mining (VI, 46): They obtained this income from the mainland and from mines. The income from the gold mines in Skapte Hyle alone was usually eighty talents a year and that from the mines on Thasos itself only slightly less, so that the Thasians [...] from the mainland and the mines a total of two hundred every year, in good years probably even three hundred talents .

The investigations carried out since 1969 by Ephoria Kavala , the Greek antiquity service for the prehistoric history of the island, did not provide any evidence of the actual presence of the Phoenicians on the island or in the area of gold mining until 1992. Excavations and rich finds in the area of the Acropolis of Kastri in the south of the island have shown a settlement lasting several thousand years, which has a strong Cretomycan character for the period of gold mining. The Antiquities Service Kavala therefore put forward the preliminary hypothesis in 1992 that gold mining was not or not only carried out by Phoenicians, but also or only by Mycenaeans before the Greek settlement.

The ancient, possibly even older, precious metal mining in the east of the island remained unnoticed and hidden for centuries. The gold pits, tunnel mouth holes and shafts for underground mining were not identified or perceived as such by the numerous geologists who worked on the island, especially in the 1950s. The residents of Limena knew the southern mouth hole (M 1), the access to the Akropolis gold mine and the widening behind it as a grotto . In Paleochori, the TG 80 B pit was called the Hermit's Cave . Until it was discovered and explored, the island's wealth was explained by its income from the famous Pangaion gold mines , which in classical times belonged to the Thasites. The company Friedrich Speidel, active in the southern part of the island between 1905 and 1914, explored the Akropolis buildings for the first time and extensively examined them in places without realizing that it was one of the ancient gold mines. An early mining of copper was suspected. Julius Speidel stated 20 years later, in 1929: Despite thorough prospecting of this area, no traces of an old gold mining have been found here so that Herodotus has to call this information in any case questionable .

The discovery and exploration of the extensive underground acropolis gold mining succeeded only in the years 1965–1979 by the Archaeological Society École française d'Athènes (EfA). The mine was examined in detail in several stages. Numerous publications are available. Due to licensing reasons, the available, very clear representations and images cannot be presented here. The discovery of the older underground gold mines of Klisidi and Paläochori in the area northwest of Kinyra took place in 1979. The Max Planck Institute Heidelberg (MPI) and the German Mining Museum Bochum (DBM) were only available for a few days in 1981 Exploration and local documentation available, which were not sufficient to cover the located mine buildings in their entirety and to be able to carry out the necessary excavations in the structures. It is assumed that the buildings that have been walked on and explored represent only about 10% of those that really exist in the vicinity of Paleochori, Platanos and Klisidi. All Klisidi and Paleochori pit plans that have been drawn up have been published and are available.

Klisidi-Palaiochori mining area

The mining history of the Thasitian gold mining is as follows according to the investigations of 1981: Already in the transition from the 7th to the 6th century BC. Between the places Kinyra (the Koinyra Herodots) and Potamia (Ainyra) on the summit and southeast slope of the Klisidi-Platanos massif down to the former village of Paleochori, the surface and underground mining of gold and silver ores was operated. The adjacent map shows the location of the outcrops, excavations and underground pits that have been explored there so far. The mining was probably started by the Thracians, possibly by the Phoenicians, then by around 680 BC. Parians who immigrated to the BC BC greatly expanded and blossomed. The main phase of mining for gold and silver fell in the 5th and 4th centuries BC. Even under the Macedonians, the Romans and the Byzantines, precious metal mining was continued or resumed and continued until around the 14th century. The resumption of gold mining by the Byzantines was possibly due to the new knowledge of amalgamation, i.e. the extraction of gold from an ore in which the gold was difficult to identify due to its fineness.

The quarries in the Kinyra-Potamia series mainly follow the contact of slate / gneiss with marble, but above all the steep faults and crevices in which the solidified gold-bearing sediments are stored. These karst fillings are solidified breccias, conglomerates or loose, rounded sediments. These are mainly composed of fragments of the neighboring rocks dolomite marble and slate or gneiss, from individual minerals from these rocks, from ore fragments and a calcareous-limonitic matrix. Fe, Mn, Cu, Ag and As minerals could be determined. The gold is predominantly native in the form of platelets (10 to 810 mm long) and grains (120–810 mm long and 100–460 mm wide). The latter appear mechanically rounded or irregularly shaped, sometimes fused with pyrite, quartz or brown iron. The weight of the gold grains and platelets is between 0.0065 and 0.1143 mg. they contain 0.3 to 19% silver and on average consist of about 94% gold and 6% silver. The mean gold content obtained from mining is likely to have been 2–5 mg / g, the silver content 1.3 mg / g. Gold-bearing hydrothermal quartz veins with gold contents averaging 1.2 mg / g also occur in the Kinyra district.

In the summit area of the Klisidi (575 m above sea level) are the gold mines TG 80 E 1 to 11. The mouth of the TG 80 E 1 mine starts on the north slope, below the summit. It is probably one of the entrances to the largest gold mine ever discovered in this area. Particularly noteworthy is the widening created in the depths of the pit with 18 m NS and 15 m WO expansion.

On the southern slope of the Klisidi, above the abandoned settlement Palaiochori , the tunnel mouth hole of the TG 80 A / K 1 pit is located at an altitude of 309.6 m above sea level. The importance and extent of this pit can already be seen in the area of the tunnel mouth hole: the remains of several protective and retaining walls as well as the ruins of a Byzantine building can be found. From the extremely low tunnel mouth hole, the main route climbs slightly at around 15 degrees, around 51 m to NNW into the mountain. In its course it climbs into five different ore-bearing contact horizons and with the last drive it reaches 316 m sea level. About 40 prospecting and mining sites as well as cutting are set from the main route. Several excavation expansions with dimensions of up to 10 m in length and 5 m in width have been driven. They reach a maximum of up to 25 m from the main driving direction to the west. Numerous crossed, east-west running, steep crevices have been eradicated. They could be followed up to 6 m above the tunnel bottom and are backfilled towards the depth. In the stretches, which are often widened in a second dismantling period, and in the large widenings, there are numerous offset walls and offset pillars, often also inverted floors.

The size of the rock and the type of stratification of this backfill suggest that there was an ancient and a Byzantine mining period here. No equipment for ore enrichment could be found. The tailings moved underground and fallen on the dumps shows that crushing with a hammer was probably sufficient to pick out the ore minerals and the free gold. The remaining excavation cavities and karst caves are heavily sintered. There are ancient traces of mining on around 80% of the mining joints and ridges. i. Iron and mallet work, recognizable. There are 18 lamp niches and around 35 ceramics, pine torches and charcoal. The laboratory of the Heidelberg Academy of Sciences is between the 7th and 14th centuries for ceramics and between the 7th and 14th centuries for charcoal. Century established. Haldenkeramik is around 100 BC. Until 1400. However, these age determinations can also be traced back to occasional inspections of the mine. Stratigraphically locatable samples were not available as no excavations were carried out. With the addition of the mining archaeological findings, however, it becomes clear that TG 80 A / K 1 was operated in the archaic and classical Greek period and that mining was resumed in the late Byzantine period.

The approach of the investigation tunnel TG 80 C / K 3 (?) Is only 6.5 m west of TG 80 A in the marble-gneiss contact zone. It is also classified as antique, although a copper Byzantine coin of Emperor Alexios III can be found on the mouth hole. Angelos (1195-1203) discovered. Pit TG 80 B / K 2 is located at 410 m asl, about 100 m higher on the Klisidi slope . Behind the mouth hole there is a 5 m deep shaft, starting from this a larger widening with 3 stretches attached from it. In one of these stretches a basin made of slate was discovered, possibly representing a grave. A further exploration was not possible because the routes collapsed. In TG 80 D / K 6 is depressions and pinging each side of the road between Keramida and Gramenos, presumably caused by Kluftausräumungen or verbrochene shaft approaches.

Underground mining Acropolis / Thasos

In the 5th century BC The gold mining in the Acropolis Mountain was added. Ore management and mining are tied to the severely disturbed contact area between slate and marble, which follows the collapse of the layer with a 30 degree incline. It is a zone several meters thick with alternating layers of slate, sulphide layers and carbonate to marble areas. In the undisturbed contact area there is a 0.3 cm thick sulphide layer. The gold was found in pockets, breccias, fissures and crevices in the form of grains 1 to 30 mm in size. The highest gold grades were 27 mg / g, the average grades 4 mg / g Au and 5.4 mg / g Ag.

Two tunnel mouth holes lie below the Pan Sanctuary, the southern main access M 1 at 117 m above sea level, the western M 11 at 138 m above sea level. The deposit is exposed by a tonnage main route that extends in a north-westerly direction under the Acropolis over a length of about 230 m to a depth of about 10 m above sea level. Numerous cross-sections, parallel sections, widenings and thaws are set off from the main section in a westerly direction. Further deeper mouth holes in the direction of the city are certainly there, but broken. A vertical rise of the weather of about 60 m height probably ends below the western retaining wall of the Athenaion. The routes have the classic rectangular cross-section with an average height of 0.90 m and a width of 0.6-0.8 m. Over 850 m distances were measured. The largest quantities of ore were extracted from expansion. The widenings in the access area M 1 reach an extension of 35 × 15 m. There are numerous traces that prove that the hard rock was driven in using mallets and irons.

The main phase of mining for gold and silver lasted until the 4th century BC. Chr. Even under the Macedonians, the Romans and the Byzantines, precious metal mining was continued or resumed. Since the ancients knew how to locate the ore-bearing strata and tunnels and to mine the usable ore, further mining is no longer an option today due to the lack of economically viable reserves.

Zinc / silver ores

Mining company Speidel

Around 700 years after the last lead / zinc / silver ore mining operated by the Byzantines on the island of Thasos , at the beginning of the 20th century international interest arose in a resumption of the exploitation of the rich, well-known ore deposits. Due to the ownership structure, however, access to the island was difficult and the entrepreneurial risk was high. German industrialist Friedrich Speidel (born 1868 in Pforzheim ,. Died 1937) succeeded in 1903 in lengthy negotiations by the Turkish Sultanate a concession for the exploitation of calamine to gain -Occurrence on Thasos. In a lease agreement with the Khedives in Kavala for the extraction of these ores in Vouves near Limenaria and in 1905 also near Sotiras (Thasos) and Kallirachi in the west of the island for a period of 40 years. In total, it was an area of 50 km² with 13 individual concessions.

The mining company Fr. Speidel, Thasos-Pforzheim built from July 1903, from the early Archaic to Roman mining disregarded remaining, deeper ores mainly in mines, but also in numerous underground outcrops, and operational preparation, calcination of calamine ores and shipped the products . Old stockpile material was also picked up and processed. The rich raw galmei was harvested on the spot as lump ore and plucked. From 1919 onwards, the poor and fine ores were transported to the central washing machine in Limenaria, where they were mechanically processed using washing ore from all pits with an output of 300 t / day. The high baryta content in the washed calme concentrates caused a problem.

The lump ore was calcined in four brick-built shaft furnaces with a capacity of 20–22 t of calcined calamine per shift. The calcination of the calamine (fine calamine) and the processed products was carried out in several rotary kilns (Oxland ovens) of 12 m length and 0.8 m diameter.

The largest open pit was built from 1904 in Vouves , northeast of Limenaria , with a length of 400 m, a width of 50 to 70 m and a depth of 30 to 40 m. The mined, roastable lump ores contained approx. 40% Zn and 1–2% Pb. The poor washing ore obtained had a zinc content of 12 to 20%, the lead content was 3–8%. A 2 km long mine train and a 220 m long Bremsberg brought 400–500 t of conveyed goods to the central system in Limenaria every day. Horses and mules were used for the ascent of the box tipping wagons.

In Sotiras , the second largest mining was operated from 1905, which, like in Vouves, followed the ancient mining. From 3 tunnels and 2 open-cast mines above, 20,000 t of raw galley with 30–32% Zn and approx. 60,000 t of washing ore with 15–20% Zn were extracted. A calcining furnace was located in the pit for the lumpy raw galley. The fine and overgrown material with a daily output of approx. 200 t was transported to a loading facility at Skala Sotiros and from there by ship to Limenaria via a mine train 2.5 km in length and 3 brake mountains.

In Marlou , southeast of Kalirachi, between 1907 and 1912 5,000 t of roastable calamine ore with an average of 38% Zn were extracted from open-cast and underground mining. Here, as in all of the other mines mentioned below, ox wagons or pack animals were used to transport ore to the next boat loading point.

In Padia (Papadhia) 3 tunnels were excavated and some 100 tons of lead almei were extracted, in the Rachoni district, in Agrelea, Spilios, Pachys and Korifi, 3 pits, 2 shafts and a tunnel were excavated.

Between 1904 and July 1914, Speidel produced a total of 155,857 t of raw ore from the above-mentioned companies. During this period, 18,357 t of lumpy raw calamine with approx. 32% Zn and 98,238 t of calcined calamine with approx. 42% Zn were shipped.

The following auxiliary operations and facilities were connected to the central operation in Limenaria : a power plant with three diesel engines of 250, 160 and 25 HP to generate electricity to supply the treatment, the Oxland ovens and the water pumps; a sack house for the packaging of the calcined galmeis, a workshop and the loading facility. The company, which had been successful for over 11 years, had to be closed at the beginning of the First World War . In July 1914 the lease rights were placed under Sequester and the entire operation was shut down. The Speidel company was expropriated.

The facilities were occupied by French forces at the beginning of the war and looted as enemy German assets, and the buildings destroyed. The management building and various outbuildings were preserved and served as a war hospital for English officers.

The merits of Friedrich Speidel jun. and his nephew, Dr Julius Speidel, about the development and the economic boom of the island at that time, the knowledge of the deposits and the subsequent continuation of ore mining are still undisputed today. The Greek government intended to honor this by setting up a mining park and museum in Limenaria / Thasos. The project was kicked off by the EU with € 600,000, but failed miserably: the unpublished project and profitability study possibly came to a negative result. Concerning the “museum”, the renovation of the Palati, which was carried out at the same time, was improperly completed, so that the building is falling into disrepair.

SAMM / Vieille Montagne

In 1925 G. Bogeret, Liège / Belgium, bought the 13 concessions for the mining and processing of zinc, lead, silver, iron and copper ores on behalf of the Belgian mining company Vieille Montagne for 40 years . The SAMM (Société Anonyme Hellénique Métallurgique et Minière) was founded. The Speidel plants were rebuilt, the calcination modernized, five steel rolling kilns built by the Krupp company, and the company was supplied with ores from the above-mentioned mining operations and with dump material. Despite the efforts to keep operations going during the Great Depression in 1929, production had to be shut down due to difficulties in ore preparation and processing as well as the fall in zinc prices in 1930. It was not until 1933 that ore mining was resumed and continued until 1936.

The merchant Georgos Apostolopoulos from Kavala took over the SAMM after the end of the Second World War, on December 31, 1944, but without resuming operations.

Iron and manganese ores

There are numerous iron-manganese deposits on Thasos. Iron ores were mined in Elia in the south of the island and on Acropolis Mountain in Limenas Thasou as early as ancient times (11th – 7th centuries BC) . Another underground mining from Roman times was found in Metamorphosis near Kallirachi with widely ramified, irregular mining sites. The routes are mostly only 0.6 meters high and could be explored up to a length of 40 meters. Larger widenings are also available. Clayey hematitic and limonitic ores with pyrite, copper pyrites and gold (2.5 mg / g Au) were probably extracted. Large-scale iron and manganese ore mining began in the 1950s.

SAMM / Apostolopoulos / Chondrodymos

The merchant Georgos Apostolopoulos, Kavala, was the owner of SAMM (Société Anonyme Hellénique Métallurgique et Minière), founded in 1925, with a concession area of about 42 km² in the western and southern parts of the island since 1944. Since 1934, the entrepreneur Aristides Chondrodymos, Athens, worked there in various places with mining outcrops. As early as November 1952, on the basis of a lease agreement with SAMM / Apostolopoulos, he was mining iron ore in the Mavrolako opencast mine, in concession no.7, the southern part of concession no.3 was shipped via Skala Maries mainly to the Georgsmarienhütte of Klöckner-Werke AG and to the United Austrian Steelworks. The ore quality averaged 46% Fe, 2% Mn, 0.2% Cu and 10% SiO 2 . The company was advised by Klöckner: the geologist at Klöckner-Industrieanlagen Duisburg, Dr. Hermann Jung, was stationed in Limenaria since 1954. Chondrodymos received further advice from Professor Dr. G. Dorstewitz from the Clausthal Mining Academy . After a total production of probably 1.6 million t and the exhaustion of the economically recoverable reserves, which were already limited by thick slate and marble coverings towards the end of 1958, the operation was stopped in 1962. At that time the opencast mine was about 450 meters long, 75 to 150 meters wide and up to 60 meters high. Iron ore was mined by Chondrodimos in Kokkoti west of Theologos (1955), on the Ais-Matis Mountain via Limenaria (1956 to July 1957), manganese ores in Sellada near Kallirachi (1953) and in Vathos in small quantities.

SAMM / Fried. Croup

In May 1954, the Friedrich Krupp company , Essen / Germany, began with a first assessment of the lead-zinc ore deposits within the 13 SAMM concessions and in July 1955 with the first investigations in the old quarries and on the dumps.

Despite the fact that the Speidel company had to give up in 1914 not because of the exhaustion of the deposits, but because of the outbreak of war, it became clear that the ores still to be found and the existing stockpile material did not enable economic extraction and processing. The original plan to resume non-ferrous metal mining could not be realized. The investigations were finally extended to the iron ore deposits within the concession area. After the first outcrops in Koumaria and Koupanada a rehearsal took for shipment held at the beginning of the 1956th Subsequent sales concluded in 1957 led to the acquisition of 100 percent of the SAMM shares and thus the concessions by Fried. Croup, food. Associated with this was the use of state-owned buildings, facilities and facilities. Hans Schmid acted as operations manager and Erich Haberfelner as chief geologist , both from Fried. Krupp GmbH raw materials , Essen.

The SAMM mined limonitic iron ores on the southern slope of the Ais-Matis mountain in the opencast mines Koumaria (12 outcrops), Platania, Mersini and Apideli and limonitic-hematitic ores in the Maries valley in the Koupanada opencast mine. In addition to mechanized drilling and loading work, a considerable amount of plowing work was required for the separation and enrichment of the ores, especially for keeping barite and marble. The extracted, hand-separated ore was separated on inclined sieves using gravity into lump ore (about 45% share) and fine ore (about 55% share) and by local entrepreneurs over five and eight kilometers by truck to the stacking area at the loading point in the bay east of Limenaria - today Metalliabucht - transported. The average ore quality for all ore mines was 45–49% Fe, 2.5–3.1% Mn, 0.43–0.77% BaO, 0.01–0.12% Cu, 6–12% SiO 2 . The total output per man and shift was around 10 t for raw ore mining and 3 t for shipping ore (values from 1960).

The ore was initially loaded from the ore heaps of the lower stacking area via hand-loaded mine wagons from the Friedrich Speidel company on mine tracks to the loading chutes at the two landing stages of the loading mole. After the construction of a 75-ton bunker with a loading chute, which was loaded by means of a charger and truck from both the dump of the upper and the lower stacking area, the loading capacity could be increased significantly. The ore was drawn from the chutes into the Mahonen (lighter). The four own mahons were dragged by two chartered kaikis to the ore carriers lying in the roadstead. There, the ore initially had to be shoveled into loading nets. The large amount of time required for this was no longer necessary when the barges were finally equipped with self-made loading buckets with a capacity of 2 t. The ore-filled nets and buckets were picked up by the ore freighters' winches using loading gear, hoisted into the holds and emptied. The charging capacity was 2500–3000 t in 24-hour operation. A total of around 530,000 t of fine and lump ore were shipped from 1956 to 1963. Most of the iron ore was exported to Austria to VÖEST , but also to Germany to the Bochumer Verein, the Krupp ironworks in Rheinhausen and the Thyssenhütte in Duisburg.

The entire company employed up to 250 workers (January 1958). The requested extension of the concession contract, which expired in 1963, was tied to the condition of the Greek side to build a processing and agglomeration plant to supply the Greek steelworks Chalywourgiki in Eleusis with pellets. In the case of the medium-grade ores remaining on the deposits, the extraction of which in a larger open-cast mine would have required the handling of a high proportion of unsalted material, as well as inevitably high investments for ore enrichment, economic operation was called into question. In addition, comparatively inexpensive, rich ores forced their way onto the international market. The SAMM operation was closed in September 1963 and the concession was given up. The SAMM was liquidated in 1969.

Post-operative activities

After the high-grade iron ore reserves in the two mining companies Chondrodymos (1962) and SAMM / Krupp (1964) had been exhausted, the Greek authorities tried to find new concessionaires. The Organization for the Industrial Development of Greece (OWA) had already decided in 1960 to thoroughly examine the remaining iron ore deposits on the island of Thasos. With French funding, the Bureau de Recherche Géologique et Minière (BRGM), Orléans, together with the Institute of Geology and Mineral Exploration , IGME , Xanthi, started investigations in this regard. The different occurrence areas were prospected and examined with about 2200 meters of drilling, 1700 meters of which in Mavrolako. At the same time, the BRGM carried out a plan for the enrichment of the ores for use in the iron and steel works. The inspection of the result of the overall study was finally limited to a publication of the ore reserves in 1984. However, it is very likely that the profitability for a renewed mining operation was negative.

In 1964, Chondrodymos made a renewed attempt, together with the Greek Bank for Industrial Development (ETBA), to reactivate iron ore mining on Thasos and to build a pelletizing plant. Bulgaria also showed a certain interest in this connection at the time.

50 years later, in September 2013, it was announced that the English company Tynagh Iron Ore Mines Ltd. (since 2014 Natural Resources Global Capital Partners Ltd. ) has applied for exploration work. These related to the exploration of various ores of metals such as iron, copper, zinc, lead, silver, manganese and gold, as well as the minerals barite and pyrite, occurring in the nomos Kavala. Of the 23 applications, 9 were for concession areas in the west and southwest of the island of Thasos and 14 for the mainland, the Pangeo . The authorities responsible in the approval process raised objections that led to the project being rejected.

Metal extraction

The island of Thasos can look back on a highly developed metal extraction that began around three and a half thousand years ago and thus plays an important role in the Aegean region. Probably in the late Bronze Age , at the latest in the early Iron Age , there was intensive ore smelting that lasted until the Byzantine period .

Bracht were mainly occurring in the west of the island ores galena , sphalerite , pyrite , marcasite , iron - and manganese oxides , as well as chalcopyrite , arsenopyrite and Argentite with the gaits barite , calcite and quartz .

Lead, copper, silver and iron were smelted, metals that were found in a wide variety of artefacts on the island and used in numerous Thasitian coins. Due to the investigation of slag heaps of considerable extent and finds of furnace ceramics, numerous smelting sites were determined at various places, mainly in the area around the town of Kallirachi , as well as in the southern area of Skres, and in an area in the south of the island and the origin of the ores used was determined by means of archaeometallurgical investigations to be determined.

Even the earliest smelting operations that took place on Thasos were not carried out in a primitive way in depressions in the ground, but relatively large furnaces of up to about 1 m in height with a capacity of a few kilograms were used. After the melting process had ended, the furnaces were probably destroyed, so that only ceramic fragments could be found on the melting sites and in the slag heaps.

The oldest metal artifacts melted on the island to date were found west of the Acropolis of Kastri on the burial ground of Tsiganadika , near a slag dump there. These are lead patches of vessels. A lead weight and a lead plate were found in the “Kentria” burial ground on the southwest slope of the Acropolis. These artifacts come from the transition from the late Bronze Age to the Early Iron Age (12th century BC), as well as from the 10th – 8th centuries. Century BC The lead ores used are likely to come from the prehistoric mines of Vouves and Sotiros, which were smelted in Tsiganadika.

The more recent extraction of silver in classical times from recovered lead by means of selective oxidation ( cupellation ) is documented on Thasos by the finds of litharge pieces and a gelatin plug. The extraction of silver and copper from the ores was almost complete at that time, while the extraction of lead was no longer carried out carefully, as lead was no longer used very widely at that time.

lead

The oldest metal artifacts so far were found on the island west of the Acropolis of Kastri on the burial ground of Tsiganadika , near the local slag heaps. These are lead patches of vessels. A lead weight and a lead plate were found in the Kentria burial ground on the southwest slope of the Acropolis. These artifacts come from the transition from the late Bronze Age to the Early Iron Age (12th century BC), as well as from the 10th – 8th centuries. Century BC At that time, lead metal extraction took place without desilvering the melt (without cupellation ). The smelting there concerned the use of lead and silver ores, mainly from the mining of Vouves, which were in the area of activity of the settlers of Kastri, but possibly also ores from the Sotiros deposit.

From the Hellenistic period, copper-rich lead slag was found in Padia . Even younger, from Roman times (420–600 and 330–440), charcoal, slag and galena come from Marlou near Kallirachi.

In the agora, in the amphitheater and in the Artemision of Limena, iron clips cast with lead were found to hold structural elements from classical antiquity (550–450 BC) together. The smelting sites and the ore origin of these artefacts have not yet been determined.

copper

In the settlement and in the grave fields of Kastri , 59 copper artefacts were unearthed, 9 of which are proven to have been made from Thasitic copper ore, the rest from imported ore. According to previous knowledge, the only possible smelting of copper ore for this purpose is the smelting of the Padia saddle , which has been proven between the 14th and 7th centuries BC. Has taken place. Decisive for this is the dating of furnace ceramic fragments from the thin slag dump there. The low lead and high copper contents in the slag indicate copper smelting at this point. However, it could only have been a few tons of molten metal. Copper slag has also been found in Padia from the Roman period.

From the end of the 4th to the beginning of the 3rd century BC. Brick fragments, pottery and pottery shards come from the area of the old mining for copper-containing ores in Koumaria .

Even younger, between the end of the 3rd and the beginning of the 2nd century BC. BC, the approximately 5,000 tons of copper slag on the heap next to the Makrirachi quarries could be dated. This is a melting point that is considered to be the most important in the west of the island for the smelting of sulphidic copper ores. Pottery from the 3rd century BC can also be found in the Makrirachi mining tunnels. Has been found.

Overall, however, copper production was insignificant on Thasos in ancient times. The Thasitic copper was probably mainly used as a coin metal.

Silver lead

Since the late Iron Age, in antiquity, in the Hellenistic period, in the Roman and in the late Byzantine period, lead ores containing silver were mined and smelted, with presumably long interruptions up to around 1000 AD. The total amount of silver extracted on the island is estimated to be a few tons, with more than 1,000 tons of lead being a by-product. Around 50,000 tons of slag were estimated at all known lead-silver smelting sites in the west of the island.

In the most important smelting area on the island of Kallirachi , north of the Ais Matis - Dikefalos-Kathares mountain ridge, there are six former mining operations and six slag heaps and litter sites with a slag tonnage of an estimated 30,000 to 40,000 t within a radius of 2 km. The slag dump of Skoridia is 1 km northwest of Kallirachi, from a mountain shoulder down the slope to the south with a distribution area of about 50 m × 50 m and a thickness of 1 to 1.5 m. The amount of slag is likely to be around 10,000 t. Kiln ceramics, slag, lead and litharge finds indicate lead and silver extraction in the period between the 3rd century BC. BC and 8th century. The largest smelting site in the Kallirachi area was Aermola . The dump is located about 1 to 1.5 km northeast of Skoridia and 1 km south of Sotiros on a slope that slopes to the north. The slag tonnage can amount to around 20,000–30,000 t. The lead-silver ores from the mining operations of Sotiros, possibly also from Sellada, are likely to have been smelted here within the time period mentioned for Skoridia. At the Agii Anagiri chapel , about 1 km east of Kallirachi, pieces of slag with thick-walled pottery were found. However, this may be secondary storage. The area of Kallirachi also includes the copper smelting sites of Padia (possibly as early as 12th century BC, but also Roman times) and Makrirachi (around 3rd to 2nd century BC).

The Skres smelting site is located in the southern smelting zone . Slag is scattered on the slopes in an area of approx. 100 m × 50 m. The content of the slag dump is likely to be 3,000–5,000 t. The discovery of a cone made of lead oxide and an iron sow indicate that silver was extracted by cupellation . The smelting plant is between the 5th century BC And dated Roman / Byzantine times. At least some of the ores smelted in Skres come from nearby Kokkini Petra. In the Metalliabucht, east of Limenaria , fragments of furnace and vessel ceramics, bricks, lead and igloo lead have been found and dated, so that lead or silver production, possibly from Vouves ore, is also expected there.

iron

There is no evidence that the ocher mining in Tzines and Vaftochili in the younger Paleolithic was associated with iron ore smelting on the island.

In the southwest of the island there are iron slag deposits at Tsiganadika, Karoklia, Luvistria, Vambakies, Elia, Oxia and at Cape Salonikios. This is the smelting of iron ores, which took place in the 11th and 10th centuries BC. To be dated. This metal extraction was possibly connected to the Kastri settlement that existed at the time.

From the Temple of Artemis in Limena a layer of iron slag is documented that was smelted in the early colonization period in the 7th century BC. Should be related.

Industrial park and museum

From July 2002 the Institute for Geological and Mining Research ( IGME ) examined the economic feasibility of an industrial culture project for the presentation of the calamine extraction, processing and shipping company of the Speidel company. The first visible result was the restoration of Speidel's headquarters, the Palati in Limenaria . This building should serve as a museum for the overall project. The project was financed by the European Union with € 600,000. The feasibility result should be available in mid-2008, but has not been published despite inquiries from the responsible authorities in Brussels and Athens. Presumably the project is impractical due to a lack of profitability. The use of EU funds remained uncontrolled.

The restoration of the Palati by the IGME remained incomplete, so that the building is again left to decay. It remains essentially unprotected and in danger of immediate collapse due to erosion of the soil beneath its foundations .

The Speidel-Palati is not founded on crystalline rock, but on coastal conglomerates that occur exclusively on the southwest coast of the island of Thasos, between Cape Kephalo and Skala Potos. It is probably about young tertiary educations. They consist of alternating layers of rounded slate and limestone pebbles the size of a fist or head and finer sandstone sections that are cemented with a calcareous binder. The conglomerates are severely attacked by the abrasive effects of the sea surf, weathering and fissures, and they form steep walls that descend vertically to the lake, which are often gnawed like grottos at sea level.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Ch. Koukouli-Chrysanthanki, G.Weisgerber: Prehistoric Ocher Mines on Thasos. In: Actes du Colloque International, Limenaria / Thasos, 26. – 29. Sept. 1995. ISBN 2-86958-141-6 , pp. 129-144.

- ↑ P. Tsompos, K. Laskaridis: Η εξόρυξη μάρμαρου στη Θάσος , p. 39.

- ↑ M. Vavelidis, E. Pernicka, G. Wagner: In: DER ANSCHNITT. Supplement 6, pp. 113–124 (Geology)

- ↑ W. Lieder, J. Heckes: In: DER ANSCHNITT. Supplement 6, pp. 125–130 (measurement).

- ↑ G. Weisgerber, A. Wagner pp. 131–172 (mining); Ch. Koukouli-Chrysantaki: In: THE GATE. Supplement 6, pp. 173–179 (archeology).

- ↑ T. Kozelj, A. Muller: In: THE LEADING EDGE. Supplement 6, pp. 180-197.

- ↑ IGME, Xanthi: Prospectus material on the occasion of the project presentation, September 16, 2005.

- ^ Tremopoulos Michalis: Symbol of the Greek-German friendship and cooperation

literature

- J. Speidel: Contributions to the knowledge of the geology and deposits of the island of Thasos. Dissertation 1928, Freiberg 1929.

- A. Peterek: Geomorphological and fractional tectonic development of the island of Thassos (Northern Greece). Dissertation University Erlangen-Nuremberg 1992.

- Th. Cramer: Multivariate origin analysis of marble on a petrographic and geochemical basis. Dissertation, Berlin 2004 (PDF).

- Ch. Koukouli-Chrysanthaki: Μεταλλεία , Πρωτοιστορική Θάσος. Τα νεκροταφεία του οικισμού Κάστρι, Μερος Α, Υπουργείο Πολιτισμού, Δυμοσιέυματα ττου αρχλολου τγίούερχαιου γιτούερχαιου γιτοίερχαιου τγίούερχαιου τγίοεερχαιου τγκοεερχαιου τγίούερχλολου. 45, ISBN 960-214-107-7 , pp. 674-684.

- C. Perissoratis, D. Mitropoulos: Late Quaternary Evolution of the Northern Aegean Shelf. In: Quaternary Research. 32, 1989, pp. 36-50 (This paper received in the year 1987 the annual award of the best geological paper in Greece, by the Athens Academy of Science).

- Lectures: Thasos Matieres Premieres et Technologie de la Prehistoire a nos Jours. Actes du Colloque International, Limenaria, Thasos, 26.-29. September 1995, ISBN 2-86958-141-6

- P. Tsompos, S. Zachos: Η γεολογία της Θάσου και η σημασία της στην προσφορά ορυκτών πρώτων υλών , pp. 15–24

- P. Tsompos, K. Laskaridis: Η εξόρυξη μάρμαρου στη Θάσος , pp. 39–47

- T. Kozeli, Manuela Wurch-Kozeli: Les traces d'extraction a Thasos de l'antiquite a nos jours , pp. 49-55

- J. Herrmann: The exportation of dolomitic marble from Thasos , pp. 57-74

- J. Herrmann, V. Barbin, A. Mentzos: The Exportation of Marble from Thasos in Late Antiquity: The Quarries of Aliki and Cape Fanari , pp. 75-90.

- S. Angeloudi-Zarkada: Εξόρυξη και χρήση του σχιστολίθου και του γνευςίου στη Θάσου , pp. 91-100.

- Ch. Koukouli-Chrysanthaki, G. Weisgerber: Prehistoric Ocher Mines on Thasos , pp. 129-144.

- Magazine DER ANSCHNITT. Supplement 6, Association of Friends of Art and Culture in Mining e. V., Bochum 1988, ISBN 3-921533-40-6 .

- M. Vavelidis, G. Gialoglou, E. Pernicka, A. Wagner: The non-ferrous metal and iron-manganese deposits of Thasos , pp. 40-58

- G. Gialoglou, M. Vavelidis, A. Wagner: The ancient lead-silver mines on Thasos , pp. 75–87

- A. Hauptmann, E. Pernicka, A. Wagner: Investigations on the process technology and the age of the early lead-silver extraction on Thasos , pp. 88–112

- M. Vavelidis, E. Pernicka, A. Wagner: The gold deposits of Thasos , pp. 113–124

- W. Lieder, J. Heckes: Markscheiderische recording of two gold mines near Kinyra on Thasos , pp. 125–130

- G. Weisgerber, A. Wagner: The ancient and medieval gold mining of Paleochori near Kinyra , pp. 131–153

- G. Weisgerber, A. Wagner, G. Gialoglou: The ancient gold mining on the summit of the Klisidi near Kinyra , pp. 154-172

- Ch. Koukouli-Chrysanthaki: The archaeological finds from the gold mines near Kinyra , pp. 173–179

- A. Muller: La mine d'or de l'acropole de Thasos , pp. 180-197

- G. Weisgerber: Comments on ancient mining technology on Thasos , pp. 198–211

- E. Pernicka, A. Wagner: Thasos as a source of raw materials for non-ferrous and precious metals in antiquity , pp. 224–231

- N. Herz: Classical Marble Quarries of Thasos , pp. 232-240

- N. Epitropou et al .: The discovery of primary stratabound Pb - Zn mineralization at Thassos Island , L 'Industria Mineraria, N. 4, 1982.

- N. Epitropou, D. Konstantinides, D. Bitzios: The Mariou Pb - Zn Mineralization of the Thassos Island Greece , Mineral deposits of the Alps and of Alpine Epoch in Europe, HJ Echneibert, Springer - Verlag, Berlin-Heidelberg, 1983.

- N. Epitropou et al .: Le mineralizzazioni carsiche a Pb - Zn dell 'isola di Thassos, Grecia , Mem. Soc. Geol., H.22, 1981, pp. 139-143.

- P. Omenetto, N. Epitropou, D. Konstantinides: The base metal sulphides of W. Thassos Island in the Geological Metallogenic Frame work of Rhodope and Surrounding Regions , International Earth Sciences Congress on AEGEAN Regions, October 1-6, 1990, Izmir -Turkey.

- P. Omenetto, N. Epitropou, D. Konstantinides: Mineralizations a Pb - Zn comparables au type 'Mississippi Valley'. L'example de l'ile de Thassos (Macedoine, Grece du Nord) , MVT WORKSHOP, Paris, France, 1993.

- A. and G. Schwab : Thassos - Samothraki, 1999, ISBN 3-932410-30-0 .

See also

- North Aegean Shelf

- Oil and gas in the North Aegean

- Friedrich Speidel

- Thasitic Peraia

- Pangaion

- Lekani Mountains

- Skapte hyle