Book printing in Venice

Venice was the most important center of European book printing from the late 15th century until the late 16th century. Liturgical texts, works of Greek and Latin classics, religious books of Judaism, sheet music, maps and atlases as well as scientific books were printed. Letters were used or newly created for Latin, Greek, Aramaic, Arabic, Croatian and Serbian texts. From the 15th century alone, more than 4,000 printed products and the names of 150 printers working in the city are known. Venice was a leader in typography , book illustration and, since Aldus Manutius, also in the philological quality of the text editions.

Innovations

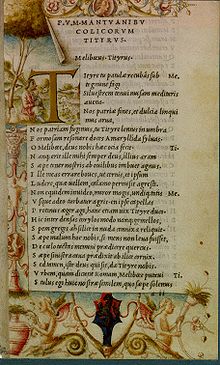

Major innovations in the book industry were tested and introduced for the first time in Venice. While Gutenberg and the early German printers mainly used Gothic fonts for printing, the Antiqua prevailed as the common typeface in book printing in the Romance countries . The first Antiqua typefaces were cut in Strasbourg in 1467, but were perfected by the French Nicolas Jenson in Venice. The Antiqua typefaces cut by Francesco Griffo at the instigation of Aldus Manutius became the style for all important later typographers. Griffo also cut the right-sloping italic for the new paperback formats of the Aldus-Offizin.

Aldus Manutius introduced punctuation to letterpress printing.

The custodians , forerunners of page counting, were first used in the Tacitus edition of 1470 by Arnold Therhoernen, a Cologne resident in Venice, in a printed book.

In 1476 , the Augsburg-born printer Erhard Ratdolt provided a book with a title page for the first time, which contains almost all the elements of a modern title page - with the exception of the author - including a short preface, which should now find its place on the laundry slip . The title page is clearly set off from the following text by a woodcut frame.

The printing of music with movable type was invented by the Venetian printer Ottaviano dei Petrucci .

history

15th and 16th centuries

- Luca Antonio Giunta the Elder (1457–1538)

- Gabriele Giolito de 'Ferrari

- Francesco Griffo , also Gryffo (1450–1518)

- Nicolas Jenson (around 1420-1480)

- Zacharias Kallierges

- Aldus Manutius (1449-1515)

- Erhard Ratdolt (1447–1527)

- Pietro dei Ravani, also Petrus Ravanus (1516–1528 active in Venice)

- Franz Renner

- Giovanni Rosso , (active in Venice 1480 - 1519)

- Johannes de Spira , also Johannes von Speyer († 1480)

- Wendelin von Speyer (active in Venice 1468 - 1477)

- Giovanni Tacuino , also Giovanni da Tridentino (1492–1541)

- Nikolaos Vlastos , also called Blasto

The most important printing locations for incunabula, the so-called incunabula from the early days of European letterpress printing, were the German cities of Strasbourg with 491 and Cologne with 434 copies, followed by Venice in third place, which is the place of printing for 387 of the 607 incunabula printed in Italy . While in Germany mainly Bibles and other spiritual texts were printed, there was interest in Venice from the very beginning in the publication of Greek and Roman authors, for which there was great demand among the humanists at the University of Padua in Venice .

The printers who settled in Venice soon after the invention of the printing press and printing with movable type by Gutenberg found favorable conditions for their business here. Venice had not yet lost its rank as the dominant trading nation, even if it gradually had to surrender its political importance as a local authority to the Ottomans. There were still close networks of trade routes and business contacts as well as lively diplomatic and cultural relations with the economic centers in Europe. A climate of economic and intellectual freedom, religious tolerance, the proximity to Padua, a center of humanistic studies, created ideal conditions for the flourishing of printing and the publishing industry.

In 1469 the Germans Johannes and Vendelin de Spira (or Johannes and Wendelin von Speyer) settled there and in 1470 they printed the first book in Italian, the Canzoniere by Francesco Petrarca . In the same year, the Frenchman Nicolas Jenson, who was born in Champagne , joined the Speyrer's workshop and designed various series of fonts for their dispensary. At the beginning of the 16th century there were over 100 printers and publishers, and for the next few decades Venice was the undisputed center of book printing in Europe. Venice became a model for Europe both in terms of the quality of the printing and the beauty of the letters developed here, the quality of the texts and the principles of the publication of texts.

The humanist and printer Aldus Manutius came to Venice in 1489 , a memorable date for Venice's printing art. Aldus revolutionized book printing with his printing press.

At this point in time, the production of books had multiplied, but due to the lack of care and ignorance of the uneducated printers who could not understand the foreign-language texts, the texts were full of errors and inconsistencies. In addition, the old mistakes in the manuscripts were reproduced again and again. The downside of the new book industry's freedom from guild restrictions was stiff competition, unfair practices, quarrels, and insecurity. The quality of the books suffered as a result and the educated and wealthy public was disappointed, sales of the prints pouring onto the market had stalled since 1472/73.

The first editions that had been critically reviewed came from Aldus Manutius's office. As a trained humanist and philologist, he compared the available manuscripts of Greek and Roman authors, corrected errors and was thus able to publish editions of previously unknown quality and accuracy. Instead of the usual small editions of no more than 500 copies, his books came out in editions of up to 1,000 copies. Aldus had the stamps cut by renowned artists for his prints, such as the Bolognese stamp cutter Francesco Griffo , from whom the first oblique antiqua came that Aldus used in his Aldinen . The space-saving cursive was particularly suitable for the printing of small-format books, the Aldinen named after Aldus, which were a great sales success due to their excellent print quality, the accuracy of the texts and the handiness of the leather-bound volumes. They are top products of the Venetian art of printing and are still coveted by collectors and bibliophiles today.

Music, sheet music printing

The usual method of printing music at the time was woodcut . Books with notes were almost exclusively liturgical books like missals and Gradualbücher .

- Lucantonio Giunta

- Johann Hamman von Landau (active 1483–1509)

- Ottaviano Petrucci (1466–1539),

- Petrus Rabanus, also Pietro dei Ravani (active in Venice 1516–1528)

- Ottaviano Scotto (* around 1444, † around 1499)

- Johann Emerich von Speier (active 1487–1500)

- Antonio (1538–1569) and Angelo Gardano (1540–1611), music publishers

Both required a great deal of effort, which was bypassed by many printers at first by printing the staff, rubrics, and sometimes also notes in various operations, but leaving as much space as possible for handwritten entries. The first printed sheet music in Venice was a gradual from 1482 from Ottaviano Scotto's off-press . As a result, the Venetian sheet music printers were so successful that Venice became a center for music for decades. Of 80 missals (incunabula) in Italy that have been preserved, 50 come from Venice alone, with the German printers Hamman von Landau and Emerich von Speier alone accounting for 35. The books were sold all over Italy, but also in France, Spain, England and Hungary. From 1482 to 1509, Hamman from Landau worked as a printer in Venice. Out of 85 prints from his office, 51 were prints provided with notes or staves for handwritten notes. Almost all of them were missals or other liturgical books for the Latin rite .

In 1498, Ottaviano Petrucci , who came from Umbria, was granted the privilege of printing notes for 20 years by the Signoria . Petrucci is considered to be the first music publisher in Venice. His invention of sheet music printing with movable type revolutionized sheet music printing and also brought him great economic success. Around 1501 he published his first printed sheet music under the title Harmonice Musices Odhecaton , scores of canzons by well-known composers in polyphonic setting. Two more volumes appeared in quick succession. Since Petrucci, like all publishers of the time, acted on his own account and was protected by the strict printing privilege of Venice, the profit fell entirely to him with no shares for the composers whose names were not mentioned.

Maps and atlases

The printers of Venice were able to build on a rich tradition of producing and perfecting postage cards and the so-called isolariums in cartography . The first printed maps of Venice corresponded to the hand-made postage cards.

- Benedetto Bordone (1460–1531),

- Gian Francesco Camoccio,

- the Giunti

- Paolo Forlan

- Giacomo Gastaldi († 1566),

- Bartolomeo dalle Sonetti,

- Giovan Battista Ramusio 1485–1557

Although Venice gradually lost its supremacy as a seafaring and trading nation in the Age of Discovery, it continued to maintain its position in the field of cartography and contributed in its own way to European expansion into America and Asia.

Unlike Spain and Portugal, which only issued their maps for use by their own fleets and locked them away again when the ships returned, Venice, which relied on precise nautical charts for the smooth flow of trade, recognized early on in the map trade as a profitable business . Venetian postage cards were used by all seafaring nations. In 1528 a map of the world was published, integrated in Benedetto Bordone's Isolario , on which the most recent discoveries - South and North America, the separation of America and Asia by the ocean - were taken into account, but Antarctica and the Asian continent, India and Africa were taken into account old Mappae mundi . Bordones Isolario from 1547 (printed by Aldus) contains a map of the world, the first known report on Pizarro's conquest of Peru and 12 maps of America, including a map of Temistitan , today's Mexico City, and a map of Japan, called Ciampagu .

The new printing processes, increased print runs through copper engraving , gave new impetus to the trade in maps and atlases. In the 16th century, Venice dominated card production in Italy, with the only significant competitor being the Lafreri office in Rome. The maps of Asia from the Gastaldi printing house, published between 1559 and 1561, were the starting material for cartographers such as Abraham Ortelius and, until the 18th century, Frederik de Wit .

Venice owes its leading position in cartography not least to the secretary of the Council of Ten , Giovan Battista Ramusio , who brought together all information relating to seafaring. Between 1550 and 1559 Giunti published his three-volume work Delle navigatione et viaggi , a treasure trove of contemporary travelogues, including a version of Marco Polo's report Il Milione and the Cosmographia dell 'Africa by Leo Africanus .

In 1564 Marc Antonio Giustinian printed a map of the world with Arabic lettering. That there were interested parties for Venetian maps in the Ottoman Empire is e.g. B. evidenced by a trip by three sons of Suleiman the Magnificent to Venice for this very purpose. In 1794, six wooden printing blocks were found in the archives of the Council of Ten, which, when put together, made a heart-shaped map of the world and which was labeled in Turkish. The layout and content of the map suggest that the author of the map had the knowledge of Ramusio at his disposal. Research suggests that this is the lost world map of Hajji Ahmed .

Towards the end of the century, Venice lost its position in cartography to the Netherlands.

17th to 19th century

With the loss of Venice's economic and political importance, the decline of the printing and book trade accelerated. The tightening of book censorship by the Curia - the Roman index was introduced in 1595 - paralyzed the book trade. Many printers closed their businesses or migrated. Nevertheless, at the end of the 17th century there were still 27 printing works and 70 bookshops, which means that Venice was able to maintain its leading position as the city of book trade in Italy.

The increasing importance of the national languages as languages of science and culture in Europe - Latin was no longer the lingua franca of the educated world - led to the formation of national book markets in the early 17th century, which served the local markets and led to economic losses in Venice.

The most important Italian typographer of the time was Giambattista Bodoni , head of the royal printing works in Parma . His classic editions are characterized by an elegant typography, careful layout and the beauty of border decorations and illustrations. Book printing in Venice also recovered, even if it could no longer build on its glamorous past. After all, there were 94 printing works in Venice again in 1753, including the renowned publishers Pasquali, Antonio Zatta and Albrizzi. Albrizzi published illustrated books that were illustrated by major artists of the time. In 1745 he published a monumental two-volume edition of the Italian bestseller The Liberated Jerusalem by Torquato Tasso with engravings and border decorations by the Venetian painter Giovanni Battista Piazzetta . Antonio Zatta specialized in the printing of maps and atlases, and Giambattista Pasquali published the first complete edition in 44 volumes of Goldoni's plays between 1788 and 1795 .

At the beginning of the 18th century, Venice developed into a lively publishing place for newspapers and magazines, which spread the ideas of the European Enlightenment. In 1710, the Repubblica di Venezia was founded on the model of the influential Giornale dei letterati d'Italia . The main authors were Antonio Vallisnieri, the poet Scipione Maffei and the scholar Apostolo Zeno . In addition to literary and aesthetic issues, legal, theological and scientific topics were also dealt with. Other important Venetian journals of those years were L'Europa Letteraria by Domenico Caminer, Il Giornale Enciclopedico and Il Giornale letterario d'Europa . In 1763, Medoro Ambrogio Rossi founded the Biblioteca moderna , which published reports on new books and literary news. The printer of lavishly illustrated books Antonio Graziosi also made a name for himself as a publisher of magazines and newspapers. In 1796 he founded the Anmerkungie del Mondo , in which important authors and writers of the time published. This magazine was also printed during the Austrian occupation and did not cease to appear until 1814.

The arrival of Napoleon in St. Mark's Square marked the end of the Serenissima . The subsequent supremacy of the Austrians meant for the printers and publishers control according to the Metternich system , ie loss of their freedom and independence and finally the end of their economic existence.

Typography and Typographers

In the 15th and 16th, Venice was a center of typography. Not only were printed with antiqua or occasionally fracur types, but new fonts were created for Greek and modern Greek texts, for Hebrew, Arabic, Armenian, Serbian (Cyrillic) and Croatian. As a rule, each dispenser made its own types.

Antiqua and Fraktur

The usual typography of the early printers was based on the medieval manuscripts that were the basis for their books. Since the printers flocking to all European countries came from Germany and brought their usual handicraft materials with them, incunabula were also initially printed with Gothic script in Italy and France. Aldus was not only a humanistic scholar and one of the most outstanding publishers of his time, he also perfected the materials and types of printing in his office. The Bolognese stamp cutter Francesco da Bologna, known as Griffo, created a new antiqua for him, which was refined several times and quickly imitated, as well as the first cursive in printing history. The Venetian chancellery script served as a template.

Arabic

Some Venetian printing houses were able to print books in Arabic script. In the woodcut illustrations of Aldus' Hypnerotomachia Poliphili , Arabic fonts appear occasionally. Overall, however, the difficulties in producing Arabic types appeared to be a hindrance to printing Arabic literature. In 1514 an Arabic book called Kitab salat as-sawa'i was printed by the Venetian Gregorius de Gregorii in Fano on behalf of Pope Julius II , probably the first Arabic book to be made entirely with movable type. The first Koran with movable type was printed in Venice in 1537/38 . It was planned for export to the Ottoman lands, but it was a business failure and the experiment was not repeated for the next 100 years.

Radolt, Melchior Sessa and the Gregorii printed translations from Arabic, including astronomical and astrological works that were important for the scientific and cultural history of Europe.

Armenian

In 1511 the Armenian Hakob Meghapart founded a printing company in Venice. He published the first book printed in Armenian in 1512, followed by a series of writings in Armenian. The most famous among them is Urbatagirk , a collection of legends and stories.

Venice is still a center of Armenian culture today. The monks of the Mechitarist Order, who live on San Lazzaro , have been publishing magazines on Armenian culture since the 18th century and maintain a library on Armenian culture. The extensive library contains around 4,000 manuscripts in the Armenian language, some of which are translated by the monks and then put into print.

Glagolitic

For the Slavic countries bordering the Adriatic, Italy was the country through which the art of printing came to southeastern Europe. Three quarters of the incunabula preserved in present-day Yugoslavia were printed in Venice. The first books printed in Croatian and in Glagolitic letters came from the workshops in Venice: a missal from 1493 and an evangelist from 1495.

Greek

In the early days of printing, Greek texts were rarely produced. Most of the Greek books of the 15th and 16th centuries were printed in Italy, especially Venice. Greek letters were mainly needed for quoting Greek classics in Latin texts. In terms of typography, each print shop was based on the available manuscripts; the types were usually cut by people who could not read Greek. Aldus Manutius, from whose print shop many prints of Greek classics come, found the best conditions in Venice for his plan to publish only editions of the classics that were carefully examined by knowledgeable humanists. He could fall back on Bessarion's library with 482 Greek manuscripts alone, but his letters were not easy to read due to the large number of ligatures and the orientation to Greek script.

Towards the end of the 15th century - the dates vary considerably between 1470 and 1493 - Nikolaos Vlastos , who came from Crete, founded the first Greek printing press in Venice together with the Cretan Zacharias Kallierges . Vlasto had new letters cut by the Cretan stamp cutter Antonios Danilos . A small number of Greek and Latin-translated philosophical texts come from her practice. In 1499 they published a Greek dictionary in folio format , the Etymologicum magnum with 233 sheets, which is characterized by its high typographical quality and which Aldus offered for sale in his catalogs. Calliergis' luxury editions were printed on parchment with initials and ornaments in red, an expensive, time-consuming, technically extremely demanding process and therefore only practiced by a few workshops.

Hebrew

- Daniel Bomberg , († 1549)

- Marc Antonio Giustinian , († 1571)

- Alvise († 1575) and Giovanni Bragadin

- Guillaume Le Bé (1525–1598)

- Mateo et al. Daniel Zanetti, (active in Venice 1593–1596)

- Giovanni di Gara, († 1609)

- Giovanni Griffo

The first books in Hebrew were printed in Italy. A total of 140 incunabula from around 40 different printing presses in Italy, Spain, Portugal and Turkey are known. The first book ever printed with Hebrew letters is Raschi's commentary on the Pentateuch, published in Reggio Calabria in 1475 . Book production in the 15th century was divided between a number of smaller officers . The most important and busiest printers were the members of the Soncino family from Speyer . By the turn of the century, the Soncino had a virtual monopoly on printing Hebrew books in Italy.

That changed with the arrival of Daniel Bomberg in Venice. Between 1516 and 1546 the Christian printer and publisher systematically published essential texts of Judaism, with a hitherto unattained elegance and perfection of typography and accuracy of the texts. Bomberg's printing types were particularly beautiful and precise and were bought by other officials across Europe. He had 6 complete briefs made by the French die cutter Guillaume Le Bé. Bomberg employed a number of eminent Jewish scholars who vouched for the quality of the texts. 1520–1522 Bomberg brought out the first complete printed edition of the Talmud in twelve volumes with the commentary by Rashi, of which the Serenissima sent a copy as a gift to the English King Henry VIII . The structure of the text and the number of pages introduced by Bomberg have become authoritative for all later editions of the Talmud. This was followed by an edition of the Tosefta , 1524/25 the so-called Rabbinical Bible ( Mikra'ot Gedolot ) and philosophical works, grammars and books on rituals according to the Greek and Spanish rites.

Both the Hebrew square types used in Germany and those cut in italics and semicursives were used. The types created in Venice and the rest of Italy were adopted by printers across Europe. In the middle of the 16th century, Bomberg grew up with powerful competitors through the establishment of printing works by the Venetians Marc Antonio Giustinian and Alvise Bragadin. The Mishne Torah des Maimonides appeared as the first Hebrew book of Bragadin in 1550 with a commentary by Meir Katzenellenbogen .

In the course of their competitive struggles, Giustinian fatally sought support from the Holy See in Rome. In 1553 the Curia then ordered the confiscation and burning of the Talmud and other Jewish writings in general. Hebrew manuscripts, incunabula and other printed matter were destroyed all over Italy. Obediently and in unusual haste, the Serenissima also obeyed the Pope's orders. The small number of early Hebrew prints in Italy before 1553 can be traced back to this book burning. Although the Pope's verdict was overturned in 1563 and Hebrew books were printed again in Venice, neither trade nor production could fully recover.

literature

- Venezia Gloria d'Italia: Book printing and graphics from and about Venice. 1479-1997 . State Library. Coburg 2000. ISBN 3-922668-17-8 .

- Mary Kay Duggan: Italian Music Incunabula: Printers and Type . Berkeley, Los Angeles, Oxford 1991. Full text , ISBN 0-520-05785-6 .

- SH Steinberg: The black art: 500 years of books . Munich 2nd, revised edition 1961.

- Steffi Roettgen in conversation with Lea Ritter-Santini: "... with them the world became Venetian". (on-line)

- European Cartographers and the Ottoman World . 1500-1750. University of Chicago 2007. Full text (PDF; 5.5 MB) ISBN 1-885923-53-8

- Jean Christophe Loubet de Bayle: Les origines de l'imprimerie venise au XVe siècle. 2006. Full text

- La stampa ebraica in Europe. 1450-1500. (PDF)

- Martin Davies: Incunabla: The Printing Revolution in Europe: Units 45: Printing in Greek.

- Donald F. Jackson: Sixteenth Century Greek Editions in Iowa.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Lexicon of the Book Industry. Vol. 2. Stuttgart 1952. p. 824

- ↑ The functions of printer , typographer , bookseller , publisher and editor cannot be clearly separated in the early days of book printing; they could be combined in one person, but at the same time there was specialization in individual functions from an early stage.

- ↑ MGG . Material part. Vol. 4, 1997. Col. 439.

- ^ Venezia Gloria d'Italia. 2000. p. 12.

- ↑ Roettgen u. Knight Santini

- ↑ Les origines romaines de l'imprimerie libanaise

- ↑ Steinberg 1961. p. 78

- ↑ Offenberg, AK: Hebrew book printing. In: Lexicon of the entire book industry. Vol. 3, 1991. pp.