Hypnerotomachia Poliphili

Hypnerotomachia Poliphili is the title of an enigmatic, well-read and influential Renaissance novel that was first published in Italy in 1499 . It was designed, set and printed in the office of Aldus Manutius in Venice . The author is a Francesco Colonna whose identity is controversial. The Venetian Dominican Francesco Colonna or a Roman nobleman of the same name, lord of Palestrina in Lazio not far from Rome, come into consideration. It may also be the same person.

title

The enigmatic title is difficult to translate. In the German secondary literature it is simply but insufficiently translated as Poliphilo's dream . This translation follows the sixteenth-century French translation, in which the text circulates under the name Le songe de Poliphile . The very fragmentary English edition, published in 1592, is more revealing and is entitled The Strife of Love in a Dream (' The Strife of Love in a Dream '). The title would have to be translated appropriately as Poliphilos Traumliebeskampf , whereby the German noun compound would correspond very precisely to the Greek.

The name of the protagonist Poliphilo mentioned in the title is a metaphor borrowed from the Greek and means roughly: The one who loves many / many. The title already reveals a lot about the content, it's about a love dream. However, it would be too brief to describe the work simply as a further development of the Romanzo d'amore in the tradition of Boccaccio , the content is far more multilayered and philosophically complex.

content

Poliphilo dreams of his lover Polia , who is constantly evading him. He goes in search of the fabulous love island Kythera in order to unite with her there. On the way he gets lost in a forest, falls asleep and dreams. The author's unusual trick is the following description of a dream in a dream. Poliphilo's dreamy path to Kythera leads him to enchanting forests, grottos , ruins, triumphal arches , a pyramid , a luxurious bath and an amphitheater . He encounters mythical creatures, allegories , fauns , nymphs , gods and goddesses and wanders through magnificent palaces and paradisiacal gardens.

Eventually he meets the Queen of the Nymphs, who asks him to declare his love for Polia. The nymphs lead him to three doors from which he has to choose the right one. His choice leads him happily to Polia. The lovers are led by the nymphs to an enchanting temple to make their mutual promise of love. On the way they encounter magnificent processions that celebrate their love. Eventually they are transferred from Cupid to Kythera, the mythical island of the goddess of love Aphrodite . It is described as a perfect garden in a circular shape, a symbol of divine origin. A canal bordered by marble statues and orange trees flows around the island. It is lined with cypress trees and divided into 20 equally sized segments, each of which represents motif gardens surrounded by climbing plants and walkways. Arrived on Kythera, Poliphilo wants to hug his lover, but she disappears like a mist and everything turns out to be a dream.

This framework , however, only fills a small part of the work. It is merely the stage and the connecting link for the detailed and detail-obsessed, sometimes several pages of the book, descriptions of the magical places and buildings, the hidden puzzles, metaphors and philosophical mind games. Most remarkable are also the strange, detailed described water and wind-powered machines, which are reminiscent of the pneumatics of Heron of Alexandria , as well as the (later) inventions of Leonardo Da Vinci .

author

The author is expressis verbis not mentioned in the book . A hint arises if you read the initials , the first letters of the individual chapters, one after the other. From this the acrostic forms : "POLIAM FRANCISCVS COLVMNA PERAMAVIT" (Francesco Colonna loved Polia very much). "Polia" is again ambiguous. It is the name of the beloved Poliphilos in the novel and also has the meaning of "much / much".

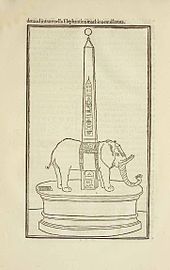

Today, Francesco Colonna , a scion of an influential Roman noble family, who is very interested in questions of architecture, is seen by the majority as the author . Colonna had the temple of Palestrina restored and rebuilt the nearby family seat, which was devastated by papal troops in 1436. He had the extensive education for such a complex book and the architectural knowledge that the detailed and knowledgeable descriptions of the strange structures in the novel suggest, including an elephant-shaped building carrying an obelisk .

The philosophical foundations of the novel are above all a secular neo -Platonism , at the center of which is the idea that Eros is the universal force that governs the relationships between humans as well as the relationships between humans and things in their environment (in the form of Perception, impressions and knowledge). This had to appear suspicious to the church and soon put the author under suspicion of heresy . It is not certain how Francesco Colonna survived the reactionary turn in the development of the Catholic Church in the last third of the 15th century after the death of the humanistically oriented and enlightened Pope Pius II (Enea Silvio Piccolomini).

A more recent thesis takes the view that the Hypnerotomachia Poliphili is a coded message and that the printer of the work, Aldus Manutius, was also the author.

Linguistic design

The book is written in a remarkable mixture of Latin , Latinized Italian , newly invented Latinisms and 15th century Roman Italian, which maximally challenges the reader's linguistic competence. Any text examples from the book may illustrate this:

“Et ardua cosa è lassare quello che alcuna fiata nel'animo è impresso, enervare non facilmente si pole. D'indi dunque fue lo exordio et origine, che io simplicemente irretito et complicato in queste vilupante rete et fallace decipulo et in questi subdoli, caduci, incerti, fugaci et currently i laquei et argutie d'amore mancipato. "

or

"Cum voluptici acti, cum virginali gesti, cum suasivi sembianti, cum caricie puellare, cum lascive riguardature, cum suave paroline illo solaciabonde blandicule me condusseron."

or

“Iustissamente se potrebbe concedermi licentemente de dire che nell'universo mundo magnificent unque fusseron altre simigliante opere né excogitate né ancora da humano intuito vise, ché quasi diciò liberamente arbitrarei che da humano sapere et summa et virtuosa simificii et summa et virtuosa potentia simificii potersi excitare né di invento diffinire. ”

In technical passages, construction instructions are given, for example how to determine the ratio of font width to font height by converting a circle into a square:

“Et erano eximie littere, exacta la sua crassitudine della nona parte et poco più dil diametro dilla quadratura.”

In addition, there are also passages (mainly inscriptions) in Hebrew , Arabic and Greek as well as Egyptian hieroglyphs , mathematical notes, geometric and architectural construction plans, modern hieroglyphs and picture puzzles. Due to its complex linguistic nature, the number of people who have actually read the novel is likely to be manageable, but the secondary literature is quite numerous.

pressure

The in Offizin of Aldus Manutius in Venice resulting pressure is still admired landmark of early art of printing. The typeface used, which today belongs to the French Renaissance Antiqua typeface, is similar to the De Aetna-Type from the same office that was used a few years earlier . As was customary with humanists, an Antiqua type was used and not a Gothic minuscule . The Antiqua had been developed around 30 years earlier by Nicolas Jenson in Venice on the basis of the humanistic minuscule as a typeface. It is still the most widely used font for Latin alphabets today and has only developed marginally. This makes the printed image of the book surprisingly modern, which is reinforced by the rich illustration . The 172 woodcuts integrated into the text by an unknown artist are of masterful execution. The use of hieroglyphics as well as Hebrew and ancient Greek fonts in printing was a novelty for this time. If you compare the work with the Gutenberg Bible , which is only 43 years older , the rapid progress in printing technology becomes clear.

The Antiqua typeface created by Francesco Griffo was trimmed in 1923 for the Monotype Corporation under the name Poliphilus .

Distribution and importance

The Spanish literary scholar and horticultural artist Emanuela Kretzulesco-Quaranta takes the view that the content of the book was inspired by the unhappy love of Lorenzo the Magnificent for Lucrezia Donati (* around 1450; † 1501).

The first edition of Hypnerotomachia Poliphili, published in 1499, initially received little attention, the book was far ahead of its time. Only the new edition in 1545 was a phenomenal success.

The novel was able to develop its greatest influence in the garden art of the Renaissance . The ideal view of ruins, influenced by the ruined city of Rome in antiquity , unfolded in garden architecture. "Debris mighty vaults and colonnades , mixed of old plane trees , laurels and cypress trees along with wild bushes" and topiarische boskets , pergolas , statues (which did not exist in medieval gardens), obelisks, Amphitheater, mazes, canals and fountains are elements from the novel which were modeled on the pleasure gardens of the Renaissance. The ars topiaria , the artful pruning of trees and bushes, created further sculptural forms in the gardens. This is particularly evident in the gardens of the Medici villas . Some more examples of the immense influence of the book on the garden architecture of the Renaissance: the Sacro Bosco in Bomarzo, the garden of the Villa Aldobrandini , the garden of the Villa Lante in Bagnaia , the Boboli garden in Florence and the garden of the Villa d'Este in Tivoli . Elements from the dream of Poliphilo (artificial ruins, temples, nymphaea ) can be found in European garden art up to the end of the 18th century, i.e. more than two hundred years later.

The French edition of Hypnerotomachia Poliphili, published by Iaques Keruer in Paris in 1546 under the title: Hypnerotomachie, ou Discours du songe de Poliphile, deduisant comme Amour le combat à l'occasion de Polia , became a much-discussed bestseller in the lavish, witty and humanistic educated environment of King Francis I. The book was such a great success in France that by 1600 three new editions were made. The English first edition from 1592 was amateurish and incomplete, but nevertheless extremely successful. Since the anniversary year 1999, several complete translations have appeared: a modern Italian as part of the edition by Marco Ariani and Mino Gabriele, a comprehensive and verbatim English, a Spanish and a Dutch. A German translation with a comment added to the text has also been available since 2014.

reception

The philosophically educated Pope Alexander VII was a great lover of the Hypnerotomachia Poliphili . When an ancient obelisk was found during construction work on the Piazza della Minerva in Rome , he suggested that it be included in the redesign of the square. He commissioned the Italian sculptor Gian Lorenzo Bernini to design a memorial (made in 1667 by his student Ercole Ferrata ), in which the obelisk rests on an elephant , whose model was a fairground elephant in Rome . The baroque work in front of the Roman Santa Maria sopra Minerva was probably inspired by the novel.

In 1999 the University of Trier dedicated a comprehensive, interdisciplinary series of lectures to the Hypnerotomachia Poliphili .

The philosopher and literary scholar Umberto Eco , an expert and collector of incontinence prints , described the Hypnerotomachia Poliphili as perhaps the most beautiful book in the world.

literature

Modern editions (with commentary)

- Francesco Colonna: Hypnerotomachia Poliphili . Edizione critica e commento a cura di Giovanni Pozzi e Lucia A. Ciapponi, Editrice Antenore, Padova 1968 (repr. 1980)

- Francesco Colonna: Hypnerotomachia Poliphili . A cura di Marco Ariani e Mino Gabriele, Adelphi, Milano 1998 (repr. 2004, 2010), ISBN 88-459-1941-2 [facsimile of Edition 1499 with Italian translation and detailed commentary]

Modern translations

- Francesco Colonna: Hypnerotomachia Poliphili, The Strife of Love in a Dream . Translated by Joscelyn Godwin, London 1999 [English translation, reprinted several times] ISBN 978-0-500-28549-7

- Francesco Colonna: Sueño de Polífilo . Edición y traducción de Pilar Pedraza Martinez, [annotated Spanish translation] Barcelona 1999, series: El Acantilado , volume 17, ISBN 978-84-95359-05-6

- Francesco Colonna: De droom van Poliphilus (Hypnerotomachia Poliphili) [Dutch translation by Ike Cialona with commentary in 2 volumes]. Athenaeum - Polak & Van Gennep 2006, ISBN 978-90-253-0668-7

- Francesco Colonna: Hypnerotomachia Poliphili, interlinear commentary version . Translated and commented by Thomas Reiser [German translation with notes inserted in the text], Breitenbrunn 2014, series: Theon Lykos . Edited by Uta Schedler. Volume Ia. ISBN 978-1-4992-0611-1

- Hypnerotomachia Poliphili Francesca Colonny . [Partial Polish translation of approximately the first 100 pages with an introduction to the history of literature, by Anna Klimkiewicz], Krakow 2015, ISBN 978-83-233-3908-3 .

Secondary literature

- Silvio Bedini: The Pope's elephant . Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart 2006, ISBN 978-3-608-94025-1 , pp. 212-213.

- Matteo Burioni: The I of architecture. Dreamwalking Architectures in the Hypnerotomachia Poliphili. In: Andreas Beyer , Ralf Simon , Martino Stierli (eds.): Between architecture and literary imagination. Fink, Munich 2013, pp. 357-384 ( academia.edu ).

- Esteban A. Cruz: Hypnerotomachia Poliphili: Re-discovering Antiquity through the Dreams of Poliphilus . Trafford Publishing, 2006

- William S. Heckscher: Bernini's Elephant and Obelisk . In: The Art Bulletin , Vol. 29, 3, September 1947, pp. 155-182.

- Emanuela Kretzulesco Quaranta: Les Jardins du Songe. "Poliphile" et la Mystique de la Renaissance . Les Belles Lettres, Paris 1986, ISBN 2-251-34480-2 .

- Leonhard Schmeiser: The printer's work. Research on the book Hypnerotomachia Poliphili . Edition Roesner, Maria Enzersdorf 2003, ISBN 978-3-902300-10-2 .

Web links

- Richly illustrated presentation of the Hypnerotomachia Poliphili (English)

- Hypnerotomachia Poliphili in the complete catalog of incandescent prints (GW number GW07223)

Digital copies of the 1499 edition:

- Hypnerotomachia Poliphili. Bavarian State Library, Munich.

- Hypnerotomachia Poliphili. Herzog-August-Bibliothek Wolfenbüttel.

- Hypnerotomachia Poliphili. Biblioteca de la Universidad de Sevilla (Fondo Antiguo).

- Hypnerotomachia Poliphili. Boston Public Library.

French version:

- Woodcuts from the French edition with iconographic descriptions, in the Warburg Institute Iconographic Database

Individual evidence

- ^ Leonhard Schmeiser: The work of the printer . Edition Roesner, Maria Enzersdorf 2003 ( review by perlentaucher )

- ↑ Emanuela Kretzulesco Quaranta: Les Jardins du Songe. "Poliphile" et la Mystique de la Renaissance. Les Belles Lettres, Paris 1986, ISBN 2-251-34480-2

- ^ Jacob Burckhardt : The culture of the Renaissance in Italy. Reclam, Stuttgart 1987, p. 217. - Jacob Burckhardt: The culture of the Renaissance in Italy. An attempt . Ed .: Konrad Hoffmann (= Kröner's pocket edition . Volume 53 ). 11th edition. Alfred Kröner Verlag, Stuttgart 1988, ISBN 3-520-05311-X , III. Section, Chapter 1, “The Ruined City of Rome”, p. 137 .

- ↑ Germain Bazin: DuMont's history of the horticultural art. DuMont, Cologne 1990, ISBN 3-933366-01-1 , p. 59 f.

- ^ Caroline Holmes: garden art. Prestel, Munich 2001, ISBN 978-3-7913-2463-0 , pp. 32-43.

- ^ Graziano Paolo Clerici: Tiziano e la “Hypnerotomachia Poliphili” . LS Olschki, Firenze 1919, WorldCat

- ↑ Silvio Bedini: The Pope's elephant. Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart 2006, ISBN 978-3-608-94025-1 , pp. 212-213.

- ^ William S. Heckscher: Bernini's Elephant and Obelisk . In: The Art Bulletin , Vol. 29, 3; September 1947. pp. 155-182.

- ^ Umberto Eco, Jean-Claude Carrière : The great future of the book. Conversations with Jean-Philippe des Tonnac . Munich 2010, Carl Hanser Verlag, p. 121, ISBN 978-3-446-23577-9