incunabulum

As incunabula (from Latin incunabula pl. Diapers, cots) or incunabula are between the completion of the Gutenberg Bible in 1454 and 31 December 1500 with movable letters printed books and broadsheets referred.

In terms of format , typography and illustration , cradle prints were initially shaped by the appearance of medieval manuscripts , which changed to modern letterpress printing with technical and economic developments from the beginning of the 16th century . They were produced by named printers who either sold their products themselves or through so-called bookkeepers . Incunabula are evidence of the beginning of the technically supported dissemination of written material in Europe and are now a valuable cultural asset .

The number of incunabula preserved worldwide is estimated at around 28,500 works with a total of around 550,000 copies. Book printing works from the subsequent early 16th century are sometimes referred to as post incunabula or early prints .

To the subject

The restriction to designate only printed works published up to December 31, 1500 as "incunabula" is a convention of book and library studies of the 20th century based on older directories in order to ensure an overview of the holdings. Completely arbitrary, this agreement is not, however, because of the 16th century won the first decade typography and sentence , even though numerous prints were clear of technical sophistication in this time produced which had the appearance of earlier decades.

The metaphorical term "incunabula" for a print refers to the early days of letterpress printing, when a print and its production were still in the cradle and in the diaper . The term is first documented in the handwritten bibliography Antiquarum impressionum a primaeva artis typographicae origine et inventione ad usque annum secularem MD deductio by Bernhard von Mallinckrodt , created between 1640 and 1657 . The German term Wiegendruck is attributed as a source in the Grimm dictionary of two other book directories from the 17th century. In the early 19th century, the term was first introduced as a technical term by collectors and later also by research and has since been established internationally (in some languages also in the Latin version) in book studies and incunabula research.

Based on the library science term, early evidence of the printmaking arts , which had been produced in various technical processes such as woodcut , copper engraving , etching and lithography , have also been referred to as incunabula in recent times , as the first examples of the respective graphic technology.

In addition to the terms incunable, cradle print and early print, the term original print can also be found in the specialist literature, especially for the first works published by the author himself .

precursor

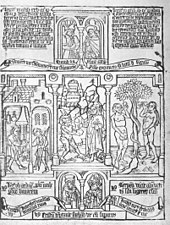

High-pressure processes were known in Germany since 1400 ; the hand operated printing press for printing z. B. of playing cards and single sheet prints already existed in the middle of the 15th century. Block books were created in which the double pages were completely cut out of the respective wooden printing block with image and text and the pages printed on one side could then be folded in the middle, placed against each other to turn the pages and stapled together. On the pages of a block book, pictures predominated; The negative cut of the letters was difficult, mostly the text was inserted by hand. The wooden printing block only allowed a comparatively small edition.

In the Middle Ages, the art of papermaking also reached Europe from China and Korea via the Arabic-speaking countries . In the 11th century, people in China also tried printing in individual characters , a process that required very thin paper and therefore only allowed one-sided printing and did not prevail. After papermaking began its triumphal march in Europe in the 15th century and began to inexorably displace expensive parchment , it also provided the basis for technical reproduction. The achievement of Johannes Gutenberg , who is considered to be the inventor of letterpress printing in Europe, consisted in the development of a hand casting instrument and an alloy for the production of individual letters made of metal. In 1454 he finished printing a so-called 42-line Latin Bible according to the number of lines per page , the "B42" or Gutenberg Bible ; However, he was unable to exploit his invention successfully financially.

development

Peter Schöffer , who had assisted Gutenberg in printing the B42, recognized the possibilities of using the new technology of letter production commercially. In Johannes Fust , a wealthy Mainz citizen, he found a colleague who was willing to invest money in printing. After the Mainz model, the new technique spread over about 30 years in Europe, everywhere arose Offizine called Druckwerkstätten with its own trademark.

distribution

In addition to Strasbourg, where Johannes Mentelin opened an off-press in 1458 and published the first Bible in German in 1466, and where Johann Grüninger continued the success of the first generation of printers in the 1480s , the cities of Cologne and Nuremberg formed in the 1460s and 1470s , Bamberg and Augsburg from further printing centers. Ulrich Zell from Hanau and Johann Koelhoff the Elder worked in Cologne . Ä. who came from Lübeck. Anton Koberger had been printing successfully in Nuremberg since around 1470; his print of the world chronicle by Hartmann Schedel in 1493 is one of the best known incunabula, along with the Gutenberg Bible. In Bamberg, where Albrecht Pfister worked from 1460 to 1464, the printing of German-language and popular literature established itself. Around 1468 Günther Zainer settled in Augsburg, who had learned to print from Mentelin in Strasbourg.

In the 1470s, Lübeck opened the new trade access to the Baltic Sea region; Lucas Brandis , who came from a printer family, worked here from 1473. Leipzig, which later became the German capital of letterpress printing, found its way into the new art late; Marcus Brandis was first printed in this city in 1481. In Basel, the printers devoted themselves particularly to spreading the ideas of humanism ; from 1477 on, Johann Amerbach printed and represented the writings from this group. In addition, book illustration developed into a valued art in Basel , to which the young Dürer also contributed.

Economy

Until 1480, sales of printed matter remained limited; the urban public was consistently unable to acquire the relatively small editions of 200 to 250 copies, which were still very expensive. Major church orders, for example for missal books , such as the Missale Aboense, were therefore among the most secure pillars of the young industry .

Since the increase in circulation depended on demand, attempts were made in many places to protect themselves against competition and reprint with printing privileges granted by the authorities. The printer's job became a traveling job. In Italy in particular, German printers set up offices; There are also records of German printers established in France, Spain and Sweden in the 15th century. Erhard Ratdolt from Augsburg was particularly influential in Venice, where he mainly printed astronomical and mathematical works. Aldus Manutius , the best-known Italian printer in Venice , encouraged the spread of Greek classics beyond Italy's borders with his series of Greek classics called Aldinen from 1495 .

From 1480 onwards, the Officine gradually developed into large-scale operations, consisting of publishing, manufacturing and sales, often combined with a bookbinding; the print run was 1000 copies, the books became cheaper and easier to handle. The Basel printer Johann Froben , who was important for the early 16th century and who worked at the Amerbachschen Offizin, printed a pocket-sized Latin Bible in 1491.

Content

The content of the prints followed the development of the Office to publishers and dealers, and authorship emerged . In addition to Bibles, pious (and heretical) writings, such as sermons and letters, from the 1470s / 80s onwards, book printing already covered the range of topics that has been read to this day: learned (in Latin, the European lingua franca ) , Folk and national language, world, teaching and herbal books , legal and medical, literary from Wolfram to Boccaccio , travelogues, satires and calendars; In Rome, Ulrich Han from Ingolstadt , presumably assisted by Stephan Plannck from Passau , printed the notation of a Roman Missal in 1476 . Ottaviano dei Petrucci , the inventor of sheet music printing with movable letters, is considered the first major music publisher .

With increasing production, book printing no longer only followed the client's reading needs, but also began to awaken it with the prospect of new products. However, there was a considerable business risk involved. By no means all of the officers were able to bear it, such as the business of Johann Zainer in Ulm, a relative of the Augsburg printer, who went into debt.

Manuscripts

The clerical circles throughout Europe remained skeptical of the development of the printing press; they were reluctant to set up their own officers, for example in the monasteries of St. Ulrich and Afra in Augsburg or in Blaubeuren , and they continued to commission manuscripts in the scriptoria . The scribes' workshops were initially able to assert themselves against the young book printing art by attempting to reach buyers interested in well-known literature with manuscripts that were illustrated quickly and with a sure hand by professional draftsmen, in addition to the church clients. For example, Diebold Lauber's workshop in Hagenau, Alsace, which was occupied until the 1470s, was able to produce in stock and for a while to compete with the printers' sales strategies.

The unstoppable triumph of book printing led manuscript production to one of the last great heydays in Europe, namely in illumination . As in the books of hours , breviaries and edification books , painting also declared the text in liturgical manuscripts to be a marginal note, a part of the picture. The illumination of the late 15th and early 16th centuries provided an exclusive audience with the great panel painting of the Renaissance en miniature .

Typography and typesetting

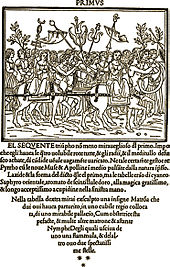

Goal and task of the printer was the text as a block in a single print space to appear; he was given ligatures and abbreviations cast based on the model of medieval manuscripts , these are letters with z. B. tildes or other characters that abbreviate u. a. Frequently occurring inflection endings in Latin were used, as were letters cast in different widths, in order to be able to bring the lines into a uniform and balanced paragraph . For example, Gutenberg had made a total of 290 different letters for his B42. According to the usual appearance of manuscripts that were initials not printed but later painted by hand and adorned the capitals nachgetragen also partly by hand and printed text in alternating red and blue (or only in red) rubricated . Illustrations were usually built into the typesetting as woodcuts ; sometimes the printing blocks were adapted to the type area by means of separate decorative strips, also called borders ; Coloring was done individually by hand in the finished print.

The prints had no title pages, the author and his subject appeared in the introductory sentences, the incipit . At the end of the work, the printer put the colophon as an Explicit , a note with his name, the place and the date of his work, and completed the print with his stamp .

The typography was based in Germany, first to the readers familiar typeface of the manuscripts. From around 1470 this approach was increasingly abandoned. In Augsburg, around 1472, the Schwabacher typeface was the predominant type in Germany until the middle of the 16th century. Adolf Rusch , Johannes Mentelin's son-in-law and inclined to the ideas of humanism , introduced the Antiqua type north of the Alps in 1474 with the printing of the Rationale divinorum officiorum ; Erhard Ratdolt, who had returned to Augsburg from Venice in 1486, printed the first type sample sheet for an Antiqua there. At the beginning of the 16th century, however, with the prints promoted by Emperor Maximilian I , the Theuerdank, a Gothic font, prevailed. Compared to Gutenberg's letters or Theuerdank, the letters had already begun to become increasingly slender and widen in favor of a stronger proportion of white and thus a brightening of the typeface, which remained legible even with a smaller font size. Colored rubrications were increasingly dispensed with, ornamented initials were now printed.

Labelling

Many incunabula do not contain any information about their production as they are available today in the imprint . Around half of all incunabula only have incomplete information on the printer, place or date of printing, the copies are “partial” or “unfirmed”. Other data must therefore be used to determine this, such as the types used , which are recorded in the “digital type repertory”. Since the printers mostly produced their typographical material themselves, an assignment of the dispenser can be made using individual characteristics.

15th century bindings

Even if a bookbinding workshop was often connected to the printing house, prints were mostly stored as unbound sheets, shipped in tons and only bound by the buyer at the point of sale. There were various logistics centers, such as Lübeck for the Baltic Sea region.

The bindings of the prints did not initially differ from those of the manuscripts. The incunabula of the first decades, all printed in folio or quarto format , were usually given a book cover made of two wooden panels, which were covered with leather or parchment, surrounding the stapled spine. Leather and parchment were often embossed with decorative ornaments that were pressed into the damp material with heated metal stamps or rollers. The decoration with metal fittings also served as a spacer for the book on top to protect the cover; Clasps made of metal or leather were used to keep the book in shape. Often, not least for cost reasons, several different printing units of the same format were integrated together.

Books, whether manuscripts or prints, were treasures in the 15th century; At the reading areas in the monastery libraries, they were often attached with a heavy chain to protect them from falling or unauthorized removal. Complete chain books are seldom preserved because later owners usually removed this bulky and unwieldy backup; Nevertheless, a number of the original bindings still show traces of the chain stop on the back cover.

In the 15th century the binding was still quite common as Kopert , which was already known from the Middle Ages ; This is a soft cover made of parchment or leather that was folded over the front of the book and attached to the spine of the bound printed matter, thus protecting the book all around. Even bindings in the form of pouch books that had an integrated carrying device were commissioned from the bookbinder by the owner of a print. With the development of book printing towards smaller and cheaper formats, the book cover also became less weighty; in the 16th century, bindings laminated with cardboard finally prevailed.

The inspection and research of the received bindings, especially their details, such as the so-called parchment waste , developed in the 20th century within the framework of book studies in the field of incunabula. Many of the original bindings were removed well into the 20th century due to severe damage or for optical reasons, and the binding and the book cover were renewed. As a result of this radical intervention, ownership entries and other symbols that enable the provenance of a book to be researched were often lost. The existing holdings are recorded in the relatively new binding research and recorded in the binding database ; With the help of the rub- throughs offered there , bindings can be assigned to the individual bookbinding workshops.

successor

Writings printed from January 1, 1501 to around 1520 are referred to as post incunabula or early prints ; sometimes the term is extended to the period up to 1530 or 1550.

Post incunable

One of the best-known postal incunabula is the Theuerdank written by Emperor Maximilian I together with two courtiers , in which the Emperor himself is the hero; The illustrated work was published by Provost Melchior Pfintzing in Nuremberg in 1517 and had its second edition as early as 1519. The emperor glorified himself in this work because he recognized the propaganda value of printing; he had all of his manifestations, which served his own, rather conservative, policy of the Reich reproduced in print. During the time of the Reformation , printing was given the opportunity for the first time in its history to act as a means of fighting and educating new ideas.

Up to 1520, many early prints were very similar in appearance to their predecessors from the previous century. In many places, successful titles such as B. the Strasbourg book of heroes , reprinted and initially left in its older form; Latin translations of works that are successful in their national language, such as Reynke de vos or Sebastian Brants Narrenschyff , opened up a European market for the books.

Outlook into the 16th century

In the 16th century the readership grew steadily, and by 1550 there was already an enthusiastic reading public in the urban milieu in Europe, although readers were not always able to write. In terms of content, printing and equipment, early prints document the speed with which the technical development in letterpress printing advanced at the beginning of the 16th century - with smaller and more manageable (and also: inexpensive) formats, based on improving casting techniques and alloys, and thus also leaner Typographies in the future and the careful design of title pages as an incentive for the buyer. With the preference for text, the prints of the first decades of the 16th century illustrate the victory of the printed word over the image, which, spread in the reduced form of printing, was subordinate to the text as an illustration and relegated the painted splendor of the manuscripts to a niche . Typographers such as Francesco Torniello , like artists, searched for the ideal form. Printing in the 15th and early 16th centuries in Europe represented a unique congruence of aesthetics and technology.

Ratings

The value of the incunabula has long been known; they are highly sought after as celestial items by collectors, are guarded as such by the libraries and are valued as sources by philologists and historians. Since the 1990s, prices for incunabula in the astronomical arena began to rise on the international market for ancient scripts; In 2002, for example, an international auction house sold a by no means unique print by Peter Schöffer and Johannes Fust for half a million pounds . At the beginning of the 21st century, illustrated single sheets appeared increasingly, especially on the international online marketplaces. Since then scientists, archivists and librarians have repeatedly accused retailers of “breaking open” old and rare books for the purpose of more profitable sales of single sheets.

Incunabula and early prints are a cultural asset of the first order for European history, not only for that of the spirit . Victor Hugo wrote:

“The invention of printing is the greatest event in history, the mother of all revolutions. She gave humanity a new means of expression for new thoughts. The mind rejected the old form and took another; he shed his skin completely and definitively like the serpent that has been his symbol since Adam.

As a printed word, the thought is more immortal than ever. It has grown wings; he has become intangible, indestructible. In the days of architecture it piled up mountains and forcibly seized a century and a place: Now it joins the birds, disperses in all four winds and is present everywhere. "

Directories

According to the current count of the holdings preserved worldwide, between 28,000 and 30,000 different editions of incunabula have been preserved, of which around 125,000 individual copies are in Germany.

The first surviving printed catalog of a collection of incunabula, the Catalogus librorum proximis ab inventione annis usque ad a. Chr. 1500 editorum of the Nuremberg City Library, was first published in 1643 by Johannes Saubert the Elder. Ä. mentioned. In the 18th century, Georg Wolfgang Panzer summarized the printed works of the 15th century in the first five volumes of his monumental work Annales typographici , published in Nuremberg from 1793 to 1797. From 1800 librarians began to mark the prints from the 15th century in older book directories or to record them separately as handwritten appendices. In the course of the 19th century the interest of collectors and increasingly also of researchers in the incunabula increased; The desire to get an overview of the printed works that had come down from the early phase of book printing led to a series of directories. The best known and fundamental for the systematic recording begun in the 20th century was the Repertorium bibliographicum by Ludwig Hain , which was written between 1826 and 1838 and listed 16,299 titles.

All prints from the 15th century (with proof of location) are listed in alphabetical order in the general catalog of Wiegendrucke (GW), which has been published by Hiersemann Verlag since 1925. Ten volumes have been published so far, Volume 11 is in preparation. This means that the letters A – H will be completely covered. The editing of the GW takes place in the Berlin State Library , which has now also created a database (with access to materials that have not yet been published in print).

The incunabula of the German linguistic and cultural area fall within the scope of the collection of German prints in the remit of the Bayerische Staatsbibliothek , which itself holds 16,785 copies of 9573 titles. To this end, the library is developing its own incunabula catalog and the incunabula census for the Federal Republic of Germany. In addition, it maintains for broadsheets the database broadsheets of the early modern period and works on international Incunabula Short Title Catalog with (ISTC). The ISTC is run by the British Library in London and is the world's largest database of incunabula with around 28,000 titles. INKA, the incunabula directory of German libraries, is maintained by the University Library of Tübingen and currently has 70721 copies.

Building on the resources mentioned above, the distributed digital incunabula library has been online since mid-2005 , in which around 1000 incunabula from the holdings of the University and City Library of Cologne and the Herzog August Library are available as digital copies.

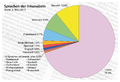

Distribution by location and language

The graphic representations are based on the dataset of the Incunabula Short Title Catalog .

literature

- Cristina Dondi (Ed.): Printing R-Evolution and Society 1450-1500. Fifty Years that Changed Europe . (Eng., It.) Studi di storia, Edizioni Ca 'Foscari - Digital Publishing, Venice 2020. ( PDF ; Permalink ).

- Oliver Duntze: A publisher is looking for an audience. Matthias Hupfuff's (1497/98 - 1520) shop in Strasbourg . Saur , Munich 2007. ISBN 3-598-24903-9

- Fritz Funke : Book customer. An overview of the history of books and writing. Documentation publishing house, Munich-Pullach 1969.

- Fritz Funke: Book customer. The historical development of the book from cuneiform to the present . Edition Albus, Wiesbaden 2006, ISBN 3-928127-95-0 .

- Klaus Gantert: manuscripts, incunabula, old prints. Information resources on historical library holdings . De Gruyter Saur, Berlin 2019 (Library and Information Practice, Volume 60), ISBN 978-3-11-054420-6 .

- Ferdinand Geldner : The German incunabula printer. A manual of the German printer of the XV. Century by place of printing. 2 volumes. Hiersemann, Stuttgart 1968–1970.

- Ferdinand Geldner: Incunabulum. An introduction to the world of the earliest book printing. (= Elements of the book and library system. 5) Reichert, Wiesbaden 1978, ISBN 3-920153-60-X .

- Konrad Haebler : Handbook of the incunabulum . Leipzig 1925, Hiersemann, Stuttgart 1979 (repr.), ISBN 3-7772-7927-7 .

- Konrad Haebler: Type repertory of incandescent prints . Haupt, Halle ad Saale 1905–; Reprint of the 1905–1924 edition, Kraus u. a., Nendeln / Liechtenstein 1968 (= collection of library studies)

- Helmut Hiller, Stephan Füssel: Dictionary of the book . Klostermann, Frankfurt am Main 2002, ISBN 3-465-03220-9 .

- Helmut Hilz: book history. An introduction. De Gruyter, Berlin 2019, ISBN 978-3-11-040515-6 .

- Albert Kapr : book design. Verlag der Kunst, Dresden 1963.

- Hellmuth Lehmann-Haupt: Peter Schöffer from Gernsheim and Mainz . Wiesbaden 2002, ISBN 3-89500-210-0 .

- Ursula Rautenberg (Hrsg.): Reclams Sachlexikon des Buches . Reclam, Stuttgart 2003, ISBN 3-15-010542-0 .

- Wolfgang Schmitz : Outline of incunabulum. The printed book in the age of media change . Hiersemann, Stuttgart 2018 (Book Library, Volume 27), ISBN 978-3-7772-1800-7 .

- Hendrik DL Vervliet (Ed.): Liber Librorum. 5000 years of book art. A historical overview by Fernand Baudin et al. a. Editions Arcade, Brussels 1972, Weber Verlag, Geneva 1973. (especially the chapters Johannes Gutenberg by Helmut Presser and The Book in the 15th and 16th Centuries by H. Vervliet)

- Barbara Tiemann (Ed.): The book culture in the 15th and 16th centuries. First half volume. Maximilian Society, Hamburg 1995, ISBN 3-921743-40-0 .

- Ernst Voulliéme: The German Printers of the Fifteenth Century . 2nd Edition. Verlag der Reichsdruckerei, Berlin 1922 ( digitized version )

Web links

- Literature on the subject of incunabula in the catalog of the German National Library

- Database of the complete catalog of the cradle prints of the Berlin State Library - Prussian Cultural Heritage (GW)

- Incunabula Catalog of German Libraries (INKA)

- TW - type repertory of incandescent prints

- British Library's Incunabula Catalog (ISTC)

- Incunable catalog of the Bavarian State Library (bsb-ink)

- Incunable census Austria

- Wolfgang Beinert: First and incunabula printer with his own office

- Index Possessorum Incunabulorum

- Digital incunabulum library of the University and City Library of Cologne

- Digitized incunabula of the Cathedral Library Freising and the library of the Metropolitan Chapter Munich

- Digitized Gutenberg Bible from the Bavarian State Library

- Gutenberg Digital . Lower Saxony State and University Library Göttingen

Individual evidence

- ↑ Felicitas Noeske: Incunabula (7). In: bibliotheca.gym. May 26, 2016. Retrieved November 18, 2017 .

- ^ Berlin State Library , Manuscript Department: Incunabula (accessed on September 15, 2019)

- ↑ On the number and its uncertainties, see Falk Eisermann: The Gutenberg Galaxy's Dark Matter: Lost Incunabula, and Ways to Retrieve Them. In: Flavia Bruni and Andrew Pettegree (Eds.) Lost Books. Reconstructing the Print World of Pre-Industrial Europe. Leiden / Boston: Brill 2016 (= Library of the Written Word 46), pp. 31–54. doi : 10.1163 / 9789004311824_003 , here p. 31 with note 2

- ↑ Incunabula. Website of the Baden State Library . Retrieved February 15, 2018; According to information from the general catalog of incunabula in Berlin 2019, around 28,000 incunabula are recorded in around 450,000 copies worldwide in public institutions.

- ↑ The first use of the term was granted in 2009 to the Dutch physician and philologist Hadrianus Junius (Adriaan de Jonghe, 1511 / 1512–1575), whose work Batavia (created from 1569, published in Leyden 1588) speaks of a prima artis incunabula , from a "first" cradle of art . Yann Sordet: Le baptême inconscient de l'incunable: non pas 1640 mais 1569 au plus tard . In: Gutenberg yearbook . No. 84 . Harrassowitz Verlag, 2009, p. 102-105 (Abstract: The origins of the term "incunabula", employed to qualify the early printed books, and especially the books printed in the XVth century, are to be found in an historical treatise of Hadrianus Junius (Batavia), published in 1588 but known from a 1569 manuscript.).

- ↑ Joost Roger Robbe: The central Dutch mirror onser behoudenisse and its Latin source . Waxmann Verlag, 2010, ISBN 978-3-8309-7345-4 .

- ↑ cradle pressure. In: Jacob Grimm , Wilhelm Grimm (Hrsg.): German dictionary . tape 29 : Little Wiking - (XIV, 1st section, part 2). S. Hirzel, Leipzig 1960, Sp. 1548–1549 ( woerterbuchnetz.de ).

- ↑ Incunabula . In: Lexikon der Kunst , Volume II, Berlin 1981, p. 400.

- ^ [1] Original print in: German dictionary by Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm. 16 vols. In 32 partial volumes. Leipzig 1854-1961. List of sources Leipzig 1971. Online version from February 28th, 2020.

- ↑ [2] Autotypes in: E. Weyrauch, Lexicon of the entire book system online. Retrieved February 28, 2020.

- ↑ Ursula Rautenberg (Ed.): Reclams Sachlexikon des Buch . Stuttgart 2003, p. 74 f.

- ^ Albert Kapr: book design . Dresden 1963, pp. 21-27.

- ^ Fritz Funke: Book customer. An overview of the history of books and writing . Munich Pullach 1969, pp. 82-89.

- ^ Fritz Funke: The book woodcut . In: ders .: Buchkunde. An overview of the history of books and writing . Munich Pullach 1969, pp. 225-238.

- ^ Mary Kay Duggan: Italian Music Incunabula . Berkeley 1992, p. 80 (English), p. 68.

- ↑ See the focus of Peter Schöffer's production in: Hellmuth Lehmann-Haupt: Peter Schöffer from Gernsheim and Mainz . Wiesbaden 2002, p. 54.

- ^ Fritz Funke: Book customer. An overview of the history of books and writing . Munich Pullach 1969, p. 68.

- ^ Fritz Funke: Book customer. An overview of the history of books and writing . Munich Pullach 1969, pp. 99-101.

- ↑ Falk Eisermann: On the trail of the strange types. The digital type repertory of incandescent prints . In: library magazine. Announcements from the state libraries in Berlin and Munich , 3/2014, pp. 41–48.

- ^ Helmut Hiller: Dictionary of the book . Frankfurt a. M. 1991, pp. 60-61, 164-165.

- ↑ Ursula Rautenberg (Ed.): Reclams Sachlexikon des Buch . Stuttgart 2003, pp. 56-57, 309.

- ^ Helmut Hilz: book history. An introduction . In: Library and Information Practice . No. 64 . De Gruyter, Berlin 2019, ISBN 978-3-11-040515-6 , pp. 41 .

- ^ Fritz Funke: Book customer. An overview of the history of books and writing . Munich Pullach 1969, pp. 103-109.

- ^ Albert Kapr: book design . Verlag der Kunst, Dresden 1963, pp. 29–34.

- ^ Victor Hugo: Notre Dame of Paris . Leipzig 1962, p. 197. Quoted from: Kapr 1963, p. 28

- ↑ British Library : Incunabula Short Title Catalog lists 29,777 editions as of January 8, 2008, which, however, also contains some printed works from the 16th century (as of March 11, 2010).

- ^ According to Bettina Wagner : The Second Life of the Wiegendrucke. The incunabula collection of the Bayerische Staatsbibliothek. In: Rolf Griebel, Klaus Ceynowa (Ed.): Information, Innovation, Inspiration. 450 years of the Bavarian State Library. Saur, Munich 2008, ISBN 978-3-598-11772-5 , pp. 207-224, here pp. 207f. - the number of issues in the Incunabula Short Title Catalog with a year of publication prior to 1501 is 28,107.

- ^ Incunabula Short Title Catalog . British Library . Retrieved March 2, 2011.