Canal du Midi

| Canal du Midi | |

|---|---|

|

UNESCO world heritage |

|

|

|

|

The apex of the Canal du Midi, to the left the former canal to the Bassin de Naurouze reservoir |

|

| National territory: |

|

| Type: | Culture |

| Criteria : | (i) (ii) (iv) (vi) |

| Surface: | 1,172 ha |

| Reference No .: | 770 |

| UNESCO region : | Europe and North America |

| History of enrollment | |

| Enrollment: | 1996 (session 20) |

| Canal du Midi | |

|---|---|

|

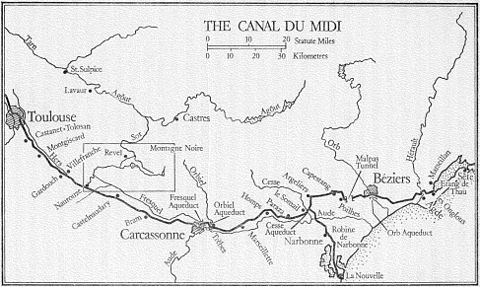

Sketch of the canal course (blue line) |

|

| Water code | FR : ---- 0142 |

| location | South of France , Occitania region |

| length | 240 km |

| Built | 1667 to 1681, planned by Pierre-Paul Riquet |

| class | Lock length only 30 m (too short for class I = Freycinet class) |

| Beginning | Crossing of the Canal latéral à la Garonne in Toulouse at an altitude of 132 m |

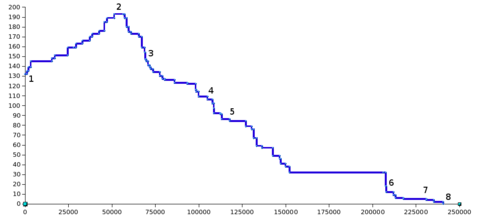

| Parting posture | Seuil de Naurouze , 5 km from Écluse d'Océan to Écluse Méditerranée , at 189 m altitude |

| The End | It flows into the Étang de Thau near Les Onglous |

| Descent structures | see Appendix lock sequence |

| Ports | Toulouse , Castelnaudary , Carcassonne , Béziers , Agde |

| Junctions, crossings | Canal de Jonction , Hérault river |

| Outstanding structures | Saint-Ferréol reservoir , Fonserannes lock staircase , Béziers canal bridge |

| Kilometrage | starting in Toulouse towards the Mediterranean |

The Canal du Midi ("Canal of the South") connects Toulouse with the Mediterranean at Sète . Its original name was Canal royal en Languedoc ("Royal Canal in Languedoc").

The canal is 240 km long and runs over the saddle between the Pyrenees and the French Massif Central . From Toulouse it leads in a south-easterly direction upwards to the apex of Naurouze (Seuil or Col de Naurouze, German "Pass von Naurouze" ) in Lauragais , then down towards the Mediterranean Sea to Carcassonne . Here it changes its course from northeast to east, reaches Béziers , the hometown of its builder Pierre-Paul Riquet , then passes the city of Agde and finally flows into the Étang de Thau . After crossing the lagoon , the ships using the canal reach the city of Sète on the Mediterranean.

The canal was completed in 1681. Its continuation at the time via Bordeaux to the Atlantic was the Garonne River , later the Canal latéral à la Garonne ( German "Garonne Lateral Canal" ) was built. A more direct connection to the Mediterranean was also established later. This branches off at about two thirds of the way between Carcassonne and Béziers into the Canal de Jonction and continues through the Canal de la Robine , on which Narbonne is located.

The Canal du Midi has been a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 1996 .

history

General

A waterway between the Atlantic coast and the French Mediterranean coast was considered desirable long before it was built in order to avoid the long and arduous route around the Iberian Peninsula . The distance between Gironde on the Atlantic Ocean and the Mediterranean Sea is only about 500 kilometers as the crow flies. Around two thirds of these, the Garonne and its Gironde estuary between Toulouse and the Atlantic, were already navigable. The sea route around the Iberian Peninsula is more than 3,000 kilometers. This trip required ocean-going ships. Piracy has often been exposed off the Spanish and Portuguese coasts . And finally the Spanish- controlled Strait of Gibraltar had to be crossed, which in certain circumstances - depending on the political situation - was difficult or expensive.

prehistory

Even in ancient times , at the time of Emperor Augustus , the Romans had thought about building a canal in southern France between the Mediterranean and the Atlantic. In order to reach their province of Gallia Narbonensis , they already built an approximately 20 km long stretch from the Mediterranean Sea as a sea canal , part of today's Canal de la Robine . Considerations were also made in the Middle Ages, in which Leonardo da Vinci was also involved. The main reason why these projects were not tackled was that it seemed impossible to supply the canal with water. The apex of a possible canal in Languedoc would be in an area in which there would not be a sufficient amount of natural water to compensate for the water consumption during lock operations and natural water losses. The rivers Hers and Fresquel , which flow away from the apex, are also not navigable in their lower reaches in summer, which would considerably lengthen the canal. It was not until the 17th century that it was recognized that enough water could be drawn from the rain-rich, not too distant area of the Montagne Noire to the apex. And they were also able to afford the high costs of a relatively long canal, which also required crossing structures with Hers and Fresquel .

The construction of the canal through Riquet

Planning and building application to the king

Henry IV and his minister Sully had given priority to a canal between the Loire and the Seine because of the difficulties encountered in a canal between the Mediterranean and the Atlantic . The construction of this Canal de Briare in 1642 also provided evidence that the passage from one valley to another by means of a canal is basically possible. The salt tax collector Pierre-Paul Riquet , born in Béziers in 1609 , has been interested in building a canal through Languedoc since his youth . He studied the Canal de Briare thoroughly. Above all, however, it was he who found the necessary water for "his canal" in the southwestern part of the Montagne Noire and finally led to the Seuil de Naurouze , which was the deepest point in the transition between the Mediterranean and the Atlantic for the apex of the future canal . He acquired all the technical and scientific knowledge necessary for the project in self-study. Over many years he designed the canal and all necessary technical structures. At his Bonrepos country estate east of Toulouse , he made an almost complete and functioning model of the canal and all the structures. In 1662 he presented his plans to the French finance minister, Jean-Baptiste Colbert . The latter convened a commission of experts who advocated the construction of the canal under the restriction that the flow of water from the Montagne Noire to the planned canal apex at Naurouze first had to be proven in practice. Riquet initially presented the evidence at his own expense in 1665: water flowed from the Revel area to Naurouze in a corresponding narrow test channel . Another year passed before the distribution of the construction costs and the future ownership structure were clarified. On October 7, 1666, the French King Louis XIV issued the edict on the construction of a canal between the two seas, which was then called Canal Royal .

Construction of the water supply

In January 1667, the extensive work began on the water supply for the vertices. The water was brought in from the Montagne Noire hills about 30 kilometers away. Some creeks flowing to the south - beginning with the Alzeau - were dammed and their water was discharged together in a trench that was parallel to the creeks and crossing the creeks ( Rigole de la Montagne Noire ) into the Sor flowing to the west . At Revel it was removed from the Sor and led through another ditch ( Rigole de la Plaine ) to the top of Naurouze . There an octagonal basin was filled with the water .

The Saint-Ferréol reservoir was built near Revel. It was designed as a dam and , with a volume of 7 million cubic meters, was the largest engineering structure in Europe at the time. It dams the Laudot stream , whose water was only intended to compensate for dry summers. Its water can feed the Rigole de la Plaine .

First construction phase between Toulouse and Trèbes

In autumn 1667, work began on the actual canal near Toulouse . Just four years later, the 52-kilometer western section of the canal between Toulouse and the apex near Naurouze was completed and went into operation. In 1674 the canal led to Castelnaudary .

The first construction phase for which Riquet was authorized extended from Toulouse via Naurouze to Trèbes . At Trèbes , the canal directly meets the Aude , which they initially wanted to make navigable. Riquet had discarded this possibility long before the canal to Trèbes was completed and in 1668 received permission and an order for another section of the canal from Trèbes to the Étang de Thau .

Second construction stage between Trèbes and Étang de Thau

The shortest connection to the Mediterranean would have led via Narbonne or to the mouth of the Aude and was still considered by Riquet when Narbonne was rejected by the state ("Port Royal") around 1664 for the construction of a new seaport. The exact timing and reasons why Riquet abandoned it are unknown. The still open choice for Sète or Agde as the location of the new seaport, he influenced for Sète with the offer to direct “his” canal near Agde into the Étang de Thau , at the northern end of which is Sète . The new port could thus be located further north, which would shorten a future coastal canal to the mouth of the Rhone . Cities in the hinterland such as Beziers could be reached from the north via the Canal du Midi.

Riquet has already had to apply for several additional loans from the state due to construction cost overruns. As a result, in addition to Colbert, he was also discredited in the Languedoc region . Those who accused him of wasting public money were met with fierce critics from Narbonne when it became clear that the canal would avoid this city. In their disappointment, they cursed Riquet and hoped that he would solve the technical difficulties, such as the passage between the Aude and the steep flank of the Pechlaurier mountain , the tunnel through the hill Ensérune ( Tunnel de Malpas ) or the lock stairs at Béziers ( Fonserannes ), wouldn't master.

The second construction phase was tackled from both sides. At Agde , the dammed Hérault river was crossed and a round sluice was built next to it, from which a branch channel branches off into the lower reaches of the Hérault into the city, thus establishing a connection to the Mediterranean. For the junction with the Libron river , a facility was created that led its brief summer floods over the canal, which was interrupted at this time (modernized today). For the crossing of the Orb at Béziers , only a small river was planned. The operation between the Étang de Thau and Béziers could already be started in 1677.

The canal to Béziers was completed later from the opposite direction . The nearby Malpas Tunnel was started in 1679 and completed in 1680. Riquet died shortly afterwards (October 1, 1680), so he did not experience the first commissioning of the entire Canal du Midi in May 1681, which the king himself initiated. His sons carried out the rest of the construction work and inherited the rights to operate the canal.

Construction workers and mortgage lending

Riquet Sr. employed up to 12,000 workers, including women. He treated her very well, he paid above-average wages and continued paying wages even in the event of illness or weather-related construction stoppages. At that time, several million cubic meters of excavated material had to be moved to build the canal. Although hardly any other technical aids were available than shovels, hoes and ox carts, the 240-kilometer-long canal was completed within just 14 years before the first continuous trial run in 1681.

The funds made available by the French king would not have been sufficient for such a rapid construction. The royal casket took over 40 percent, and the province another 40 percent. Pierre-Paul Riquet financed the rest of the costs himself, initially using his assets - gained through the rights to collect the salt tax - and later taking on considerable debts. In return, the king had given him the privilege of receiving income from the canal. It is estimated that the construction of the canal, including subsequent works, cost between 15 million and 17.5 million livres by the 20th century , of which Riquet paid for four million. The later income, however, fully amortized the investment. The sons of Riquet inherited around 2 million livres in debts, which they were only able to pay off after a long period of time, mainly because costly follow-up work was required (around 3 million livres by 1727).

Construction work by Vauban

Just one month after the canal section between Naurouze and Beziers was put into operation, the canal was drained again in June 1681 in order to be able to finish the walling of several large structures. In December 1682 it was filled with water again, and the sons of Riquet officially announced the completion of the construction work. Thereafter, the entire length of the canal was visited twice by royal inspectors. After the first voyage, further culverts had to be built for smaller streams, the floods of which had previously flowed into the canal during heavy rainy seasons, before the successful completion of the canal construction was officially confirmed in March 1685.

In the same year, when many residents complained about flooding caused by the canal, the Riquet sons asked Seigneley , the king's new finance minister (Colbert had died in 1683), for help. This prompted an investigation by the royal fortress builder Sébastien de Vauban , who recommended, designed, and had the fortress construction engineer Antoine Niquet carry out unavoidable additions and improvements . The work carried out in the years 1686 to 1694 concentrated on

- the improvement of the water supply of the canal and

- the avoidance of summer floods from the crossed streams and rivers flowing into the canal.

The Laudot brook was only able to fill the Saint-Ferréol dam again after a period of drought several months later, and the octagonal basin of Naurouze, which was intended to store the water from the Rigole de la Montagne, which had previously passed Saint-Ferréol, had become unusable due to silting up as early as 1681. That is why the Rigole de la Montagne was introduced directly into the Saint-Ferréol dam , for which a tunnel at Cammazes and the extension of the Rigole up to the dam were built. Its dam was reinforced and increased, increasing the storage volume from around 4 to over 6 million cubic meters.

Vauban initiated the construction of about 50 more culverts for smaller streams and aqueducts over the Cesse and Orbiel rivers . Both rivers were also dammed and could thus discharge additional water into the canal. At the crossing points, the freeboards of the streams, rivers and the canal were enlarged and accompanying drainage ditches were created. An aqueduct over the Orb designed by Vauban was not executed as "too ambitious and too expensive". The crossing remained at the same level, but had apparently been made less susceptible to failure than before by changes recommended by Vauban during low and high tides of the Orb .

The construction of the canal was not finished until 1694 due to the work initiated by Vauban.

Construction work in the 18th and 19th centuries

The function of the canal left by Vauban left a lot to be desired only at the remaining points of level crossing with rivers. In the period that followed, these places - with the exception of the Hérault intersection - were provided with corresponding structures. Other construction work involved connections to other canals and a short stretch of the Canal du Midi itself. Although the work started by Riquet was followed by several generations of French engineers for around 200 years, the canal appears to have been created according to the concept of a single dominant client. All builders from Vauban / Niquet (active at the end of the 17th century), via Garipuy , sen. and jun. (active in the 18th century) to Maguès / Simonneau (active in the mid-19th century) reflected on Riquet's work and emulated him.

The construction of the Canal de Jonction was completed in 1787, creating a navigable connection with the already existing Canal de la Robine , so that one can also get to the Mediterranean via Narbonne and Port-la-Nouvelle . Riquet had refused to branch the canal because of the additional water consumption in the branch line, which was not planned at the time. As a result, the Lampy dam (completed in 1782) was built in the Montagne Noir , in which additional canal water is kept in stock. The builder for both was Garipuy, jun.

The Canal du Midi has been running through Carcassonne since 1810 . During the laying work, a canal bridge was also built over the laid Fresquel , the water of which - as before - supports the feed of the canal. Two abandoned locks (five steps) have been replaced by three new locks (four steps). A canal harbor was built in and on the outskirts of the city. That of Garipuy, jun. originating project was accepted in 1786. Construction work did not begin until 1802 because of the French Revolution .

The coastal canal Canal du Rhône à Sète , which is relatively easy to build (only one lock) in the Étang de Thau and the Canal du Midi, was only started in 1777 and initially only ran as far as Aigues Mortes . Completion up to the Rhone near Beaucaire was delayed until 1828 and it was not until 1834 that the problem of keeping it free from the salt water of the sea was solved.

In 1854 the construction of the Canal latéral à la Garonne , which runs parallel to the Garonne river from Toulouse to Castets-en-Dorthe (first stage to Agen ), was completed. With it, the continuous canal connection from the Atlantic to the Mediterranean is available, the name of which Canal des Deux Mers was coined long before its creation. Before the canal latéral à la Garonne was built , the Garonne and Gironde were used between Toulouse and the Atlantic . However, the Garonne was always considered difficult and unpredictable in the upper reaches.

In 1827 the Ognon was bridged with an aqueduct. Because of the small difference in height, the canal is overflowed under the double lock between this and a weir in the canal in extreme floods. The channel is then blocked.

In 1858 the Béziers canal bridge was built over the Orb , eliminating one of the last river crossings that were prone to failure. The traffic on the canal has been interrupted for several days every year due to low or high water levels in the river, for 17 days in 1797. The builders were M. Maguès and M. Simonneau . The previously eight-step lock staircase at Fonserannes was shortened to six steps. Between the two new double locks on the other side of the Orb , the city of Béziers got a new canal port.

The traffic on the Canal du Midi had to be stopped from the beginning due to the rare but violent flooding of the small river Libron . Since this section of the canal was put into operation, the resulting soiling of the canal has been avoided with the help of a temporarily sunk barque, the deck of which was designed as a wide, transverse channel. The double structure, which is still functioning today, with several narrower transverse channels that can be quickly installed over the canal, was designed by the master builder Maguès - like the Béziers canal bridge before . The doubling allows shipping even when the Libron floods .

Recent construction work

The Sor reservoir near Cammazes , which is primarily intended as a drinking water reservoir, has existed since 1958 , from which up to four million cubic meters of water (total requirement around 90 million cubic meters) can be taken for the canal every year.

At the end of the 20th century, the canal was to be expanded for longer barges ( Freycinet-Péniche : 38.5 m long, 5.05 m wide). This plan turned out to be a wrong decision because of the additional competition to the railroad from the simultaneously built, almost parallel motorway Autoroute des Deux Mers . When the project was stopped, the locks between the Étang de Thau and Béziers and between Toulouse and Baziège and those of the Canals de Jonction and the Canal de la Robine were already enlarged. The two double locks Orb and Béziers were converted into single-stage locks. The lock staircase in Fonserrannes was to be replaced by a water wedge lift (a ship lift ). This had already been built, but soon had to be shut down again because it was not working satisfactorily.

Ownership

Although the French king and the province of Languedoc paid a majority for the construction of the canal, Riquet practically became its owner in accordance with the agreement with Louis XIV. The sons of Riquet initially had to sell shares of their inherited property in order to finance the unfinished and subsequent construction work. However, they bought back all the shares later and were able to assert themselves as sole owners when the king died in 1715 and expropriation was requested. Languedoc wanted to buy the canal for about a third of its construction costs in 1768, which the Riquet families naturally refused to do, as they had been debt-free from around 1724 and had steadily improving income. The users of the channel were against the nationalization, whereupon the purchase "offer" was withdrawn.

During the French Revolution, the canal became the property of the Republic. Only the branch of the Riquets family that remained in France was compensated for its third share. At the time of Napoleon , the two-thirds share of the other family branch was also compensated. A new canal company was created (from which Napoléon claimed 90% of the shares for himself and his new aristocracy), which finally leased the canal to a railway company for 40 years in 1858. In 1898 the canal was again owned and managed by the state.

The canal authority Voies navigables de France (VNF) has been in charge of the canal since 1992 .

Economic importance of the canal

The Canal du Midi "led the south of France into modernity". He opened up regional productions and markets for a supra-regional economic and trading area. Mail and passenger transport became faster and more convenient. Trade and traffic grew steadily, except in the years between 1858 and 1898, when the canal was leased by a railroad company, and during World War II . Only at the end of the 20th century did real competition arise from the railways and motorways. Since the canal became important for tourism at this time , it was preserved and continues to promote the economy in its region in the form of tourism .

The railway gained a high reputation when it was first introduced, at the expense of the canals and even led to the Canal du Midi being leased to a railway company, the Compagnie des chemins de fer du Midi . The canal boatmen and the employees of the canal found this decision “like a manslaughter”. The railway company neglected canal transport in favor of rail transport, which ran on a parallel route. Annual canal transport was suddenly cut in half (in 1859 to around 60 million tonnes kilometers), while rail transport soon amounted to a multiple of that (around 200 million tonnes kilometers between Bordeaux and Sète in 1860, 500 million tonnes kilometers in 1880).

When the 40-year lease expired, the Canal du Midi became the property of the French state and was able to recover and develop. It was only with the advent of the highways that canals finally lost their function for transporting goods. Nevertheless, the French state wanted to expand the entire Canal des Deux Mers for larger ships in the 1970s . In 1973 the expansion of the Canal latéral à la Garonne was completed, but it remained meaningless because of the parallel motorway that was completed in 1978. This led to the abandonment of the expansion work on the Canal du Midi.

In the 1970s, the Canal du Midi was discovered for tourism. Since then it has been used by more and more tourists with sport boats and houseboats . The many old locks that have not been enlarged and the openings in the old arched bridges are sufficiently dimensioned for this. The prevented expansion for larger ships contributed to the fact that the Canal du Midi could be declared a World Heritage Site.

The Canal des Deux Mers (from the Canal du Midi is a part) had opposed his name have little impact on shipping through the Strait of Gibraltar. Reloading to the small canal ships was only practiced during the naval blockade imposed by England on France at the time of Napoleon .

Canal structures

Locks and a boat lift

The height differences between the end points of the canal and its apex require a large number of locks . As modifications were made over and over again, their number has changed over and over again. Currently (2006) 63 lock systems with a total of 98 lock basins are in operation: 15 locks between Toulouse and the summit (ascent 57 m), 48 locks between the summit and the Étang de Thau (descent 189 m). On average, a lock has to be passed every 3.8 km. The shortest distance between two locks is 105 m (below the bridge over the channel Fresquel ), the longest 53.9 km (between Argens and lock staircase of Fonserannes ).

The locks on this canal have an oval floor plan, so that despite the narrow gates they are wide enough inside for ships lying next to each other. In addition, the curved walls offer greater stability against the earth load that is pressing on the walls from outside. Riquet opted for this shape after some of the first straight-walled locks collapsed. The concrete extensions made on some locks in the 1970s are rectangular. Renewed locks (mainly in the Toulouse area ) and newer locks (e.g. in Béziers , north of the canal bridge) are concreted in a rectangular shape.

A special attraction is the six-step (originally eight-step) Fonserannes lock staircase near Béziers , in which the ships are raised or lowered by 13.6 meters in six stages. The passage takes about 45 minutes uphill and 30 minutes downhill, with alternating times only up or down.

The round lock of Agde is an unusual lock , in which the ships can be turned by 90 degrees in order to reach the city of Agde via a secondary canal and into the Mediterranean via the Hérault River . In the course of the expansion of the canal that began in the 1970s, the round lock was enlarged. The chamber was expanded over about a quarter of the circular enclosure. In this sector the longer ships are turned. The three lock gates have remained largely unchanged. Since the extended quarter sector is also bounded by a circle, the round character of the lock was hardly disturbed by the measure.

Of the 63 locks, 30 are operated automatically and 33 by lock keepers. The lock keepers generally live at their lock; many have turned their houses and properties into little gems. They occasionally offer local products or homemade handicrafts for sale. Like the construction workers on the canal back then, the lock keepers call themselves Gens de l'eau.

A technical innovation was the Fonserannes water wedge lift , which is located directly next to the Fonserannes lock staircase and was intended to replace it. It was only in operation for a short time after it opened in 1984; due to constant defects and lack of demand, it was shut down on April 11, 2001. A similar work, the Montech water wedge lift , is located on the Canal latéral à la Garonne . It was built in 1974 and was in operation until 2009.

- Locks with different numbers of stages

Ports, a lake, bridges and a tunnel

Ports are typically rectangular widenings of the canal in cities lined with warehouses. Today they are mainly used to moor tourist boats. Even on the way there are occasionally rectangular widenings to enable or facilitate mooring or even just encounters of ships.

A special feature is the lake of Castelnaudary, which was laid out together with the canal and crossed by it and has shaped the image of this city ever since. The water stored in it also ensures the lock operation in the canal between Castelnaudary and the Mediterranean Sea.

The canal bridges a large number of streams, rivers and drainage ditches and runs through a tunnel. Roads and railways are higher up and bridge the canal. The exception is the railway, which crosses under the canal in its tunnel from Malpas with little difference in direction.

Most of the bridges of watercourses are simple so-called culverts which are located in an earth dam relatively deep below the bottom of the canal bed. The dam walls can be fixed (masonry). However , it is only a canal bridge if the canal bed is also attached and supported by a bridge. At the Canal du Midi, the canal trough and the vault bridge are always bricked. Only a newer canal bridge leading over the motorway on the outskirts of Toulouse has been concreted. From Riquet only the river Répudre was crossed with a canal bridge - the Pont de Répudre . All other larger rivers were initially crossed at the same level in a stagnation of the river. Later all river crossings with the exception of the slowly flowing Hérault near Agde were replaced by canal bridges (aqueducts). The Béziers canal bridge , which went into operation in 1858, was the last to be built and at the same time the longest .

The road and path bridges were built from local material and reflect the geology of the respective region. They lead over the canal as arched bridges. Because of the design-related small arch width, they are less than 5 m wide and should have disappeared when the canal was expanded for longer and wider ships. Its appearance is one of several criteria for the Canals du Midi to be recognized as a World Heritage Site. The narrowest bridge is in Le Somail .

The canal tunnel built for the Canal du Midi was the first in the world. The Malpas tunnel runs under the hill of Ensérune for a length of 160 meters . Just before construction began, a royal commission is said to have been announced to check whether Riquet was using the state funds effectively. Riquet felt hurt and gripped in his honor. He also deployed all construction workers and the best foremen from neighboring construction sections on the tunnel and had them work day and night for higher wages, so that the tunnel should have broken through in just six days. The commission that arrived shortly afterwards was faced with a fait accompli.

- Ports, a lake, bridges and a tunnel

Malpas Canal Tunnel , northeastern mouth hole

The Libron flood passage

At Vias the canal crosses the Libron River . In normal times this carries little water, which flows through a culvert under the canal. After thunderstorms, however, its water flow is often enormous, which requires a different solution. The high water level of the Libron is only slightly above the canal level, so that the overpassing of the stream with an aqueduct is not possible. When the tide is high , the Libron is allowed to flow through channels that are temporarily laid across the canal.

Former high water flow of the Libron via a barge temporarily sunk in the canal (original drawing)

Initially, a barque was used for this purpose, which fitted flush between the masonry canal borders and was lowered onto the canal floor. Its flat deck, which was flush with the upper edges of the walls, and a front and a rear transverse wall on the deck formed the desired channel. The work was time-consuming, which further delayed ship operations, which had been interrupted during the flood.

The final solution found in the middle of the 19th century in the form of a fully mechanized double structure is original and unique. Two lock-like chambers were built into the canal at a distance of one ship's length. Parallel to the chamber walls, which extend approximately to the level of the canal, there are additional high walls on the outside with openings that can be shut off from the river bed. There are several bridge arches leading over the chambers between the outer walls. The relatively narrow spaces between the “foot sections” of these arches form four niches on each side of the chambers, each of which normally contains a narrow wooden channel half and a raised plate. In the event of flooding, the halves of the channel hanging from trolleys on the bridge arches are pushed over the chambers until they collide in the middle. The plates, which can be rotated at their lower edge, are laid flat until their front edge rests on the floor of the respective channel half. In this position they form the bottom of the niches that is flush with the channel halves. A niche on the mountain side and a valley side together with two halves of the channel form a channel that is about twice as long. After the channel has been laid, the lifting gates (“guillotine plates”) are raised in the outer walls . The high water of the Libron can now shoot over the canal and after a few kilometers reach the open sea. The construction used prevents sediment and floating debris from entering the canal and, because of its deep location, from polluting it even over a greater length. The niches and channel halves also remain relatively clean.

With the help of this double structure, ship operations no longer need to be stopped during floods. Between the individual structures there is space for at least one ship, which only has to wait until the structure behind it is set up for flood flow and the structure in front of it is cleared for passage. In extreme floods, the Libron can flow through both structures.

- Flood passage of the Libron

The water supply

The structures of the water supply are water intakes ( prises ), water reservoirs ( basins ) and moats ( rigoles ). The water catchments consist of weirs and dams in the Black Mountains ( Montagne Noir ). The dam of the Laudot brook serves as a reservoir (reservoir of Saint-Ferréol ) for the Canal du Midi. The amount of water flowing in from the stream is small. The majority of the water that flows into the Rigole de la Montagne is stored . The latter was already routed through the tunnel built under the direction of Vauban near Cammazes into the reservoir of Saint-Ferréol (previously at the Sluice Conquet in the Sor and at Revel in the Rigole de la Plaine ). The storage volume of this reservoir made the octagonal basin near Naurouze, which was silted up soon after its commissioning, superfluous. The Rigole de la Montagne brings water from four south-flowing rivers ( Lampy dammed) and, since 1954, also from the Sor (damming near Cammazes , water extraction from the former reverse-acting Sluice Conquet ). The Rigole de la Plaine was at the time of Riquet between Revel ( Port St. Louis ) and the summit level ( Partage des Eaux in Naurouze passable) also of small boats with which building material to Naurouze was brought. The later operation remained insignificant and was stopped in 1725. The locks that existed at the time are now in ruins.

- The water supply of the Canal du Midi

planting

In order to improve the durability of the canal banks, Riquet had fast-growing trees - preferably willows - planted on embankments and irises in the water along the banks . The idea of providing the canal banks with trees throughout for both practical and aesthetic reasons finally caught on after the French Revolution. The willows had already been followed by mulberry trees for the silk industry, Italian poplars and fruit trees, for which tree nurseries belonging to the canal were established. The tree nursery manager Antoine Ferrière , who was in charge between 1787 and 1817, promoted the planting of plane trees , which today dominate the canal edges. Their roots seem to hold up the banks particularly well. Their shade reduces evaporation and the horses and workers protect them from the sun when they are towing .

A large number of the 42,000 plane trees along the canal today have been infected by the massaria disease since around 2005 . So far, the phenomenon has been described less as a disease than as self-cleaning (so-called “branch cleaning”). However, this disease has already led to the death of many trees on the canal. For example, all plane trees died in Trèbes . The plane tree cancer is caused by the fungus Ceratocystis fimbriata. Since the fungus can get from tree to tree via the canal water and the boats sailing along the canal, control is more difficult, which is why it is feared that over the next 15 to 20 years all 42,000 plane trees on the canal will fall ill and have to be felled.

business

Towing and ship propulsion

Canal ships were pulled (grained) from the shore before the introduction of steam engines and ship engines. It was only possible to sail on very wide canals. Riquet, however, presumably assumed that the majority could be sailed and, as an exception, people would take over the towing. This is indicated by the very narrow towpath under the old arched bridges for horses . The towing was mainly done with horse power, less often with human power. Horses were used on the Canal du Midi until the 20th century. A continuous towpath was usually only laid out on one side of the canal. He often crosses a bridge to the other side if it is cheaper. Adjustments were necessary in some structures. For example, canal overflows ( epanchoirs ) were each provided with a bridge for the towpath. The trees along the canal were planted outside the towpaths.

The transition to steam engines as a ship propulsion system began in the 1830s and since around 1930 almost all ships have had a diesel engine. Since the speeds that can be achieved with motor power can damage canal embankments, a speed limit of 5 knots (9 km / h) applies today.

Freight, mail and travel

From the beginning, the canal was not only used for the transport of goods, but also for the transport of mail and people. The latter could travel from Agde to Toulouse or vice versa in four days . The intermediate stages ended in Le Somail , Trèbes and Castelnaudary , where there were hostels, hotels and even small churches for visiting a trade fair. The boats used were faster and much more comfortable than the carriages on the bad roads. In the middle of each stage there was a break in which the travelers had lunch and the horses were changed. The boat was not passed through multiple locks and lock stairs, but the travelers changed to another boat, which saved time (and water). Regular passenger transport was transferred to the railroad from the middle of the 19th century.

There were two different speed classes of ships for transporting goods. Heavy ships drove an average of 6 km per hour, the faster ones - loaded with only up to 60 tons - were as fast as the passenger ships at 11 km per hour.

The canal had an economic peak in 1856, when 110 million tonne kilometers of goods were transported. In the end, the canal lost the competition against the rail traffic that would emerge afterwards. In addition, the road traffic infrastructure was getting better and better, so that in the 1980s the transport of bulk goods on it was given up.

Todays use

Today the canal is almost exclusively used for tourism.

It is mostly only used by houseboats , which can be rented along the entire route. A patent (driver's license) is not required, a brief training by the boat rental company is sufficient. In contrast, captains who sail the canal with their own boat must hold an inland navigation patent.

The flat and shady towpaths are suitable for bike tours and (long-distance) hiking.

Fishing permit holders are allowed to fish in the canal . Like all French canals, the Canal du Midi is also rich in fish.

Swimming in the canals is prohibited as the water is heavily polluted by microbes .

The use of the French channels is regulated and generally chargeable. Renters of boats pay the corresponding tax to the state indirectly through the lessor.

Course of the canal

Coordinates

- Starting point of the canal: 43 ° 36 ′ 40 ″ N , 1 ° 25 ′ 6 ″ E

- Crown position (Bassin Naurouze ): 43 ° 21 ′ 9.4 ″ N , 1 ° 49 ′ 17.1 ″ E

- End point of the canal: 43 ° 20 ′ 23 ″ N , 3 ° 32 ′ 19 ″ E

Crossed departments

- in the Occitanie region : Haute-Garonne , Aude | Herault

Major cities on the canal

Toulouse | Castelnaudary | Bram | Carcassonne | Trèbes | Capestang | Béziers | Agde

Lock sequence

The following shows the course of the canal via its locks (as of 2006), starting at its western end. The name of the lock is given, followed by the number of barrages in this lock and the height it has overcome (all steps; + = upwards, - = downwards). The lock is then removed from the starting point of the waterway. Special features are described under Notes.

| Key name | stages | Hub | km | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| - | - | 0.0 | Connection to the Canal latéral à la Garonne | |

| Béarnais | 1 | 2.62 m | 0.8 | |

| Minimes | 1 | 4.43 m | 1.8 | |

| Bayard | 1 | 6.20 m | 3.4 | |

| Castanet | 1 | 4.98 m | 15.5 | |

| Vic | 1 | 2.37 m | 17.2 | |

| Montgiscard | 1 | 3.82 m | 24.7 | |

| Ayguesvives | 1 | 4.44 m | 27.9 | up to here: length for Freycinet-Péniche |

| Sanglier | 2 | 3.73 m | 29.4 | |

| Negra | 1 | 4.00 m | 33.1 | |

| Laval | 2 | 5.48 m | 37.3 | |

| Gardouch | 1 | 2.12 m | 38.7 | |

| Renneville | 1 | 2.44 m | 42.8 | |

| Encassan | 2 | 4.85 m | 45.6 | |

| Emborrel | 1 | 3.08 m | 47.2 | |

| Océan | 1 | 2.62 m | 51.3 | Crown posture in the upper water |

| Méditerranée | 1 | - 2.58 m | 56.4 | Crown posture in the upper water |

| Roc | 2 | - 5.58 m | 57.2 | |

| Laurens | 3 | - 6.78 m | 58.4 | |

| Domergue | 1 | - 2.24 m | 59.6 | |

| La Planque | 1 | - 2.63 m | 60.8 | |

| Saint Roch | 4th | - 9.42 m | 65.4 | |

| Gay | 2 | - 5.23 m | 67.0 | |

| Vivier | 3 | - 7.23 m | 68.6 | |

| Guillermin | 1 | - 2.83 m | 69.1 | |

| Saint Sernin | 1 | - 2.46 m | 69.6 | |

| Guerre | 1 | - 2.40 m | 70.6 | |

| Peyruque | 1 | - 2.02 m | 71.7 | |

| La Criminelle | 1 | - 3.11 m | 72.2 | |

| Tréboul | 1 | - 3.19 m | 73.5 | |

| Villepinte | 1 | - 3.05 m | 77.3 | |

| Sauzens | 1 | - 2.14 m | 79.0 | |

| Bram | 1 | - 2.98 m | 80.3 | |

| Béteille | 1 | - 2.25 m | 85.8 | |

| Villesèquelande | 1 | - 2.47 m | 93.3 |

| Key name | stages | Hub | km | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lalande | 2 | - 5.82 m | 98.2 | |

| La Douce | 1 | - 2.71 m | 99.9 | |

| Carcassonne | 1 | - 3.32 m | 105.0 | |

| Saint Jean | 1 | - 2.71 m | 107.8 | |

| Fresquel Double | 2 | - 5.66 m | 108.6 | |

| Fresquel Simple | 1 | - 2.53 m | 108.7 | |

| Évêque | 1 | - 3.19 m | 112.5 | |

| Villedubert | 1 | - 2.82 m | 113.2 | |

| Trèbes | 3 | - 7.89 m | 117.9 | |

| Marseillette | 1 | - 3.70 m | 127.1 | |

| Fonfile | 3 | - 8.73 m | 130.2 | |

| Saint Martin | 2 | - 5.61 m | 131.4 | |

| Aiguille | 2 | - 5.47 m | 133.2 | |

| Puichéric | 2 | -4.63 m | 136.2 | |

| Jouarres | 1 | - 3.62 m | 142.5 | |

| Homps | 1 | - 3.14 m | 146.2 | |

| Ognon | 2 | - 5.81 m | 146.9 | |

| Pechlaurier | 2 | - 4.63 m | 149.7 | |

| Argens | 1 | - 2.41 m | 152.2 | |

| - | - | 168.1 | Junction of the Canal de Jonction | |

| - | - | 197.8 | Malpas tunnel (160 m long) | |

| Fonserannes | 6th | - 13.60 m | 205.6 | Fonserannes water lift , out of order |

| - | - | 206.8 | Béziers canal bridge over the Orb (198 m long) | |

| Orb | 1 | - 6.19 m | 207.1 | from here: length for Freycinet-Péniche |

| Beziers | 1 | - 4.24 m | 207.6 | |

| Ariège | 1 | - 2.16 m | 211.5 | |

| Villeneuve | 1 | - 2.05 m | 212.9 | |

| Portiragnes | 1 | - 2.23 m | 217.3 | |

| - | - | 225.0 | Flood passage of the Libron | |

| Agde | 1 | 0.44 m | 230.5 | Round lock max. Hub ( depending on the Hérault level) secondary connection (3rd gate) to Agde |

| - | - | 231.5 | Crossing the Hérault River | |

| Prades | 1 | - 0.44 m | 233.0 | Max. Hub ( depending on the Hérault level) |

| Bagnas | 1 | - 1.51 m | 234.3 | |

| - | - | 240.1 | Confluence with the Étang de Thau |

literature

- LTC Rolt: From sea to sea. The Canal du midi . Allen Lane, London 1973, ISBN 0-7139-0471-2 .

- Michel Adgé: Les oeuvres d'art du Canal du Midi. Conception et évolution des principaux types (1667–1857). Agde, 1983, ISBN 2-9500003-0-4 .

- Jean-Denis Bergasse: Le Canal du Midi . 4 volumes. Vol I: Pierre-Paul Riquet et le Canal du Midi dans les arts et la littérature . Vol. II: Le Canal du Midi - trois siècles de batellerie et de voyages . Vol. III: Le Canal du Midi - des siècles d'aventure humaine . Vol. IV: Le Canal du Midi - grands moments et grands sites; les canaux de Briare et du Lez-Roissy . Cessenon: Bergasse, 1982–1985.

- Jacques Morand: The Canal du Midi and Pierre-Paul Riquet. The history of the "Canal royal en Languedoc". Edisud, Aix-en-Provence 1993, ISBN 2-85744-850-3 .

- Lefrançais de Lalande, Joseph-Jérôme: Des canaux de navigation et spécialement du Canal de Languedoc . Reprint of the 1778 edition. Toulouse: APAMP, 1996. ISBN 2-908564-40-7

- René Gast: Canal du midi . Éditions Ouest-France, 2000, ISBN 978-2-7373-2475-8 .

- Michel Cotte: Le Canal du Midi - "Merveille de Europe". Belin-Herscher, 2003, ISBN 2-7011-2933-8 .

- Bernd-Wilfried Kießler : Canal du Midi. 5th edition 2008, Verlag Edition Maritim, Hamburg, ISBN 3-89225-172-X .

- Angelika Maschke, Harald Böckl: With the houseboat through southern France. 3rd edition 2001, Edition Hausboot Böckl - self-published, ISBN 3-901309-12-8 .

- Jean Morlot: Guide Vagnon de Tourisme Fluvial - n ° 7. Les éditions du plaisancier, Miribel 2002, ISBN 2-85725-302-8 .

- Voies Navigables: Canaux du Midi. Éditions Grafocarte, July 2002, ISBN 2-7416-0164-X .

- Lauriane Clouteau: Le canal du Midi; guide du randonneur destiné aux randonneurs à pied, à bicyclette, en canoë-kayak, aux navigateurs de pénichette . Les éditions du vieux crayon, 2005, ISBN 2-9516797-4-2 .

- Jean-Yves Grégoire: Canal du Midi - à pied, à vélo de Bordeaux à Sète au fil de l'eau. Editions Rando, 2007, ISBN 978-2-84182-314-7 .

- Philippe Calas: Le Canal du Midi à vélo . Edisud, Aix-en-Provence 2007, ISBN 978-2-7449-0665-7 .

- Christina Langner, UNESCO : The natural and cultural wonders of the world . Wissenmedia Verlag 2006. ISBN 3-577-14640-0

- Chandra Mukerji: Impossible Engineering. Technology and Terrioriality on the Canal du Midi. Princeton 2009, ISBN 978-0-691-14032-2 .

Movies

- The Canal du Midi. Documentary, Germany, 2011, 43 min., Script and director: Susanne Gebhardt, camera: Norbert Bandel, production: Sehmannsklub Filmproduktion, arte , SWR , series: Countries - People - Adventure, first broadcast: July 8, 2011 by arte, summary by ARD .

- Canal du Midi. Where ships have to climb. Documentary, Germany, 2001, 14:43 min., Script and director: Gisela Mahlmann , camera: Hans Jürgen Grundmann, production: SWR , series: Schätze der Welt , Filmtext & Video , u. a. with a short chronology of the construction stages.

- Canal du Midi. Une découverte inédite et interactive. Documentary, France, 2009, 65 min., Philippe Calas and Christian Salès, DVD - French, Occitan, English, Spanish, German, Italian, with 1 m long map (oldest detailed map of the canal)

Web links

- From Toulouse to Étang de Thau: brief overview with pictures

- Canal du Midi: technology and history on plans and photos

- Le site du Canal du Midi (French)

- Collection of web links on the topic of Canal du Midi (French)

- Canal guide France: Canal du Midi

- Tourist office of the Canal du Midi in Capestang

- Museum and Gardens of the Canal du Midi ("Musée & Jardins du Canal du Midi")

Individual evidence

- ^ A b Michel Cotte: Le Canal du Midi - "Merveille de Europe" , Belin-Herscher, 2003, ISBN 2-7011-2933-8 , map on p. 10

- ↑ a b Description of this pass: fr: Seuil de Naurouze

- ↑ a b http://www.canalmidi.com:/ Description and course with maps, French

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i Michel Cotte: Le Canal du Midi - “Merveille de Europe” , Belin-Herscher, 2003, ISBN 2-7011-2933-8 , pp. 171–178

- ^ LTC Rolt: From sea to sea. The Canal du midi . London: Allen Lane, 1973. ISBN 0-7139-0471-2 . P. 16

- ↑ a b L.TC Rolt: From sea to sea. The Canal du midi . London: Allen Lane, 1973. ISBN 0-7139-0471-2 . Pp. 18/19

- ^ LTC Rolt: From sea to sea. The Canal du midi . London: Allen Lane, 1973. ISBN 0-7139-0471-2 . P. 24

- ↑ Michel Cotte: Le Canal du Midi - “Merveille de Europe” , Belin-Herscher, 2003, ISBN 2-7011-2933-8 , p. 44/45

- ^ LTC Rolt: From sea to sea. The Canal du midi . London: Allen Lane, 1973. ISBN 0-7139-0471-2 . P. 37/38

- ^ LTC Rolt: From sea to sea. The Canal du midi . London: Allen Lane, 1973. ISBN 0-7139-0471-2 . Pp. 38-41

- ^ LTC Rolt: From sea to sea. The Canal du midi . London: Allen Lane, 1973. ISBN 0-7139-0471-2 . P. 47

- ^ LTC Rolt: From sea to sea. The Canal du midi . London: Allen Lane, 1973. ISBN 0-7139-0471-2 . P. 49

- ↑ a b c Michel Cotte: Le Canal du Midi - “Merveille de Europe” , Belin-Herscher, 2003, ISBN 2-7011-2933-8 , pp. 25-29

- ↑ a b L.TC Rolt: From sea to sea. The Canal du midi . London: Allen Lane, 1973. ISBN 0-7139-0471-2 . P. 50 and Appendix A

- ↑ a b L.TC Rolt: From sea to sea. The Canal du midi . London: Allen Lane, 1973. ISBN 0-7139-0471-2 . P. 52

- ^ LTC Rolt: From sea to sea. The Canal du midi . London: Allen Lane, 1973. ISBN 0-7139-0471-2 . P. 58

- ^ LTC Rolt: From sea to sea. The Canal du midi . London: Allen Lane, 1973. ISBN 0-7139-0471-2 . P. 57

- ^ LTC Rolt: From sea to sea. The Canal du midi . London: Allen Lane, 1973. ISBN 0-7139-0471-2 . P. 70

- ^ LTC Rolt: From sea to sea. The Canal du midi . London: Allen Lane, 1973. ISBN 0-7139-0471-2 . P. 82

- ↑ a b Michel Cotte: Le Canal du Midi - “Merveille de Europe” , Belin-Herscher, 2003, ISBN 2-7011-2933-8 , pp. 60/61

- ^ LTC Rolt: From sea to sea. The Canal du midi . London: Allen Lane, 1973. ISBN 0-7139-0471-2 . Pp. 84/85

- ^ LTC Rolt: From sea to sea. The Canal du midi . London: Allen Lane, 1973. ISBN 0-7139-0471-2 . Pp. 86/87 and 91

- ^ Michel Cotte: Le Canal du Midi - “Merveille de Europe” , Belin-Herscher, 2003, ISBN 2-7011-2933-8 , p. 64

- ↑ a b Michel Cotte: Le Canal du Midi - “Merveille de Europe” , Belin-Herscher, 2003, ISBN 2-7011-2933-8 , p. 172

- ↑ a b L.TC Rolt: From sea to sea. The Canal du midi . London: Allen Lane, 1973. ISBN 0-7139-0471-2 . P. 96/97

- ^ LTC Rolt: From sea to sea. The Canal du midi . London: Allen Lane, 1973. ISBN 0-7139-0471-2 . P. 98

- ^ Michel Cotte: Le Canal du Midi - "Merveille de Europe" , Belin-Herscher, 2003, ISBN 2-7011-2933-8 , 55

- ↑ a b Michel Cotte: Le Canal du Midi - “Merveille de Europe” , Belin-Herscher, 2003, ISBN 2-7011-2933-8 , p. 72

- ^ Michel Cotte: Le Canal du Midi - “Merveille de Europe” , Belin-Herscher, 2003, ISBN 2-7011-2933-8 , 51

- ↑ a b c d L.TC Rolt: From sea to sea. The Canal du midi . London: Allen Lane, 1973. ISBN 0-7139-0471-2 . Pp. 101-104

- ↑ a b c Michel Cotte: Le Canal du Midi - “Merveille de Europe” , Belin-Herscher, 2003, ISBN 2-7011-2933-8 , pp. 68/69

- ^ LTC Rolt: From sea to sea. The Canal du midi . London: Allen Lane, 1973. ISBN 0-7139-0471-2 . P. 59

- ^ LTC Rolt: From sea to sea. The Canal du midi . London: Allen Lane, 1973. ISBN 0-7139-0471-2 . P. 146

- ↑ a b L.TC Rolt: From sea to sea. The Canal du midi . London: Allen Lane, 1973. ISBN 0-7139-0471-2 . Pp. 134/35

- ^ LTC Rolt: From sea to sea. The Canal du midi . London: Allen Lane, 1973. ISBN 0-7139-0471-2 . P. 175

- ↑ a b c Michel Cotte: Le Canal du Midi - “Merveille de Europe” , Belin-Herscher, 2003, ISBN 2-7011-2933-8 , pp. 97/98

- ^ LTC Rolt: From sea to sea. The Canal du midi . London: Allen Lane, 1973. ISBN 0-7139-0471-2 . P. 144

- ↑ a b c L.TC Rolt: From sea to sea. The Canal du midi . London: Allen Lane, 1973. ISBN 0-7139-0471-2 . Pp. 62-66

- ^ LTC Rolt: From sea to sea. The Canal du midi . London: Allen Lane, 1973. ISBN 0-7139-0471-2 . P. 152

- ^ LTC Rolt: From sea to sea. The Canal du midi . London: Allen Lane, 1973. ISBN 0-7139-0471-2 . P. 113/14

- ^ LTC Rolt: From sea to sea. The Canal du midi . London: Allen Lane, 1973. ISBN 0-7139-0471-2 . P. 112

- ^ LTC Rolt: From sea to sea. The Canal du midi . London: Allen Lane, 1973. ISBN 0-7139-0471-2 . P. 148

- ^ LTC Rolt: From sea to sea. The Canal du midi . London: Allen Lane, 1973. ISBN 0-7139-0471-2 . P. 136

- ^ LTC Rolt: From sea to sea. The Canal du midi . London: Allen Lane, 1973. ISBN 0-7139-0471-2 . Pp. 128/29

- ↑ Michel Cotte: Le Canal du Midi - “Merveille de Europe” , Belin-Herscher, 2003, ISBN 2-7011-2933-8 , p. 116

- ↑ Cammazes dam on structurae.de

- ↑ Michel Cotte: Le Canal du Midi - “Merveille de Europe” , Belin-Herscher, 2003, ISBN 2-7011-2933-8 , p. 147

- ↑ Odile de Roquette-Buisson and Christian Sarramon: The Canal du Midi , Rivage / Technal, 1983, ISBN 2-903059-21-7 , p. 42

- ↑ Michel Cotte: Le Canal du Midi - “Merveille de Europe” , Belin-Herscher, 2003, ISBN 2-7011-2933-8 , p. 150

- ^ LTC Rolt: From sea to sea. The Canal du midi . London: Allen Lane, 1973. ISBN 0-7139-0471-2 . P. 108

- ↑ a b L.TC Rolt: From sea to sea. The Canal du midi . London: Allen Lane, 1973. ISBN 0-7139-0471-2 . P. 110

- ↑ a b Michel Cotte: Le Canal du Midi - “Merveille de Europe” , Belin-Herscher, 2003, ISBN 2-7011-2933-8 , pp. 80-82

- ↑ Michel Cotte: Le Canal du Midi - “Merveille de Europe” , Belin-Herscher, 2003, ISBN 2-7011-2933-8 , p. 119

- ↑ Michel Cotte: Le Canal du Midi - “Merveille de Europe” , Belin-Herscher, 2003, ISBN 2-7011-2933-8 , p. 129

- ↑ Odile de Roquette-Buisson and Christian Sarramon: The Canal du Midi , Rivage / Technal, 1983, ISBN 2-903059-21-7 , p. 41

- ^ LTC Rolt: From sea to sea. The Canal du midi . London: Allen Lane, 1973. ISBN 0-7139-0471-2 . P. 111

- ^ LTC Rolt: From sea to sea. The Canal du midi . London: Allen Lane, 1973. ISBN 0-7139-0471-2 . P. 74

- ^ LTC Rolt: From sea to sea. The Canal du midi . London: Allen Lane, 1973. ISBN 0-7139-0471-2 . P. 158

- ^ LTC Rolt: From sea to sea. The Canal du midi . London: Allen Lane, 1973. ISBN 0-7139-0471-2 . Pp. 93/94

- ↑ a b Michel Cotte: Le Canal du Midi - “Merveille de Europe” , Belin-Herscher, 2003, ISBN 2-7011-2933-8 , p. 103/04

- ^ LTC Rolt: From sea to sea. The Canal du midi . London: Allen Lane, 1973. ISBN 0-7139-0471-2 . P. 109

- ↑ Cf. Peter Kuhn: ( The plane tree and its diseases ( Memento of July 18, 2013 in the Internet Archive )), page 20

- ↑ Le sacrifice des platanes du canal du Midi

- ↑ ( PDF ( page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. )

- ↑ Le sacrifice des platanes du canal du Midi

- ^ LTC Rolt: From sea to sea. The Canal du midi . London: Allen Lane, 1973. ISBN 0-7139-0471-2 . P. 114

- ↑ a b L.TC Rolt: From sea to sea. The Canal du midi . London: Allen Lane, 1973. ISBN 0-7139-0471-2 . P. 116

- ^ LTC Rolt: From sea to sea. The Canal du midi . London: Allen Lane, 1973. ISBN 0-7139-0471-2 . P. 119

- ↑ Michel Cotte: Le Canal du Midi - “Merveille de Europe” , Belin-Herscher, 2003, ISBN 2-7011-2933-8 , pp. 85-87

- ↑ Michel Cotte: Le Canal du Midi - “Merveille de Europe” , Belin-Herscher, 2003, ISBN 2-7011-2933-8 , p. 110