Dachau Dora Trial

The Dora Trial (also Nordhausen main process ) was a war crimes trial of the United States Army in the American occupation zone in military court in Dachau . This process took place from August 7, 1947 to December 30, 1947 in the Dachau internment camp , where the Dachau concentration camp was located until the end of April 1945 . The procedure was officially recognized as United States of America vs. Kurt Andrae et al. - Case 000-50-37 called. In this trial, 19 men were charged with war crimes in connection with the Mittelbau-Dora concentration camp and its sub-camps . The trial ended with 4 acquittals and 15 convictions, including one death sentence. During the Dachau Dora Trial, five ancillary proceedings were negotiated with one defendant each. The Dachau Dora Trial was the last main trial in connection with concentration camp crimes that took place as part of the Dachau Trial .

prehistory

Of the more than 60,000 prisoners who passed through the Mittelbau-Dora camp complex with its catastrophic working and living conditions, at least 20,000 died of starvation, exhaustion, illness and severe mistreatment. When American troops reached the Mittelbau camp complex in the final phase of World War II on April 11, 1945, they found almost 2,000 dead. In the main camp itself, only a few hundred living, but mostly sick or dying prisoners could be freed. The Mittelbau concentration camp and its subcamps had already been cleared by April 6, 1945. On the death marches up to 8,000 of the 36,500 "evacuated" prisoners died as a result of exhaustion, shootings and air raids. An evacuation transport comprising about 400 prisoners left the Rottleberode subcamp on April 4, 1945, under the direction of Erhard Brauny . At Gardelegen this group of inmates met with inmates from other "evacuation transports". As the "evacuation march" could not be continued due to the close front, on the orders of NSDAP district leader Gerhard Thiele 1,016 prisoners were murdered in the Isenschnibber barn on April 13, 1945.

Against this background, American investigators from the War Crimes Investigating Team 6822 quickly began investigations to determine who was responsible for these crimes as part of the War Crimes Program , a US program to create legal norms and a judicial apparatus to prosecute German war crimes. The investigation was soon completed and the investigation report was sent to the Commander-in-Chief of the US 9th Army , General Simpson , on May 25, 1945 . Many perpetrators were soon caught and interned. Witness testimony was recorded, evidence secured and the crimes documented with photographs. These results of the investigation formed the basis for the indictment and thus the Dachau Dora trial. However , there was no planned handover of this procedure and the Buchenwald procedure to the Soviet military administration in Germany , on whose territory Mittelbau and Buchenwald were located after the withdrawal of the American troops from Thuringia on July 1, 1945. The transfer of the internees and the extensive evidence regarding Mittelbau and Buchenwald agreed for September 3, 1946 failed because no representatives of the Soviet military administration appeared at the agreed meeting point at the zone border. Previously, only 22 suspects and files relating to the Gardelegen crime complex had been handed over to the Soviet military administration. It is not clear why the Buchenwald and Dora proceedings were not submitted to the Soviet investigative authorities. Corresponding inquiries from the Soviet military administration mostly went unanswered, and the file handover offered by the American side was not accepted. A note from an American investigator shows that possibly due to unclear responsibilities with the Soviet investigative authorities, none of those responsible there wanted to make a decision. The Nordhausen procedure was finally negotiated as part of the Dachau trials.

Previously, twelve former members of the Dora-Mittelbau camp team had already been convicted under British military jurisdiction in the Bergen-Belsen trial . Franz Hößler , former protective custody camp leader, Franz Stofel , commando leader in the Mittelbauer subcamp Kleinbodungen , and his deputy Wilhelm Dörr were sentenced to death and executed on December 13, 1945 in Hameln prison by hanging. Four defendants were sentenced to prison terms and five others were acquitted. The former camp commandant Otto Förschner was sentenced to death in the main Dachau trial and executed on May 28, 1946; his successor Richard Baer went into hiding at the end of the war and died in custody before the first Auschwitz trial in Frankfurt began in 1963. The former SS medical officer at Mittelbau-Dora concentration camp, Karl Kahr , was not incriminated due to his relatively good reputation among the Dora prisoners and testified as a witness for the prosecution in the Dachau Dora trial.

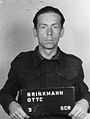

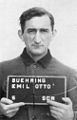

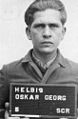

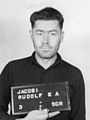

- The defendants in June 1947

Legal basis and indictment

The legal basis of the procedure was the Legal and Penal Administration , which came into force in March 1947 , based on the decrees of the Military Government .

The indictment, which was served on the defendants on June 20, 1947, comprised two main charges which were brought together under the title "Violation of War Customs and Laws." The complaint contained war crimes committed against non-German civilians and prisoners of war in the period from June 1, 1943 to May 8, 1945 in Dora-Mittelbau and the satellite camps. This was a decisive change compared to the main Dachau trial , as not only war crimes against nationals of allied states were prosecuted, but also those committed against stateless persons , Austrians, Slovaks and Italians. Crimes committed by German perpetrators against German victims went unpunished for a long time and were usually only tried in German courts later.

All the defendants were charged under a joint approach ( Common Design ) to have participated unlawfully and intentionally abuse and killings of non-German civilians and prisoners of war. Through the legal institution of the common design , the defendants did not have to prove specific crimes individually; rather, participation in the operation of the concentration camp and membership of the camp SS was already considered a war crime. The degree of individual responsibility in the common design was determined through participation in excessive offenses, the area of responsibility and rank of the accused and served as a yardstick for the sentence in the judgment.

Process participants

Colonel Frank Silliman took over the presidency of the military tribunal consisting of seven American military judges, the other judges were Col. Joseph W. Benson, Col. Claude O. Burch, Lt. Col. Louis S. Tracy, Lt. Col. Roy J. Herte, Major Warren M. Vanderburgh and the lawyer Lt. Col. David H. Thomas.

The prosecution under Chief Prosecutor William Berman consisted of American officers Captain William F. McGarry, Capt. John J. Ryan, Lt. William F. Jones and investigators Jacob F. Kinder and William J. Aalmans. Aalmans from the Netherlands was a soldier in the US Army who participated in the liberation of the Mittelbauer camp complex. As a member of the War Crimes Group, he heard the accused in preparation for the Dora trial and also worked as a translator. Aalmans wrote his experiences in this regard in his recording entitled The “Dora” -Nordhausen War Crimes Trial . These records were given to the process visitors as an information brochure to introduce them to the process.

The accused were 14 members of the SS, four prison functionaries and the only civilian Georg Rickhey , director general of Mittelwerk GmbH . Of the accused SS members, the former camp doctor of the Boelcke barracks subcamp and Hauptsturmführer Heinrich Schmidt was the highest-ranking SS leader.

The defense of the accused was carried out by the two American officers Major Leon B. Poullada and Capt. Paul D. Strader and the three German legal advisers Konrad Max Trimolt, Emil Aheimer and Ludwig Renner. From October 31, 1947, Milton Crook supported the defense team after a request by Poullada.

Process execution

The public trial began on August 7, 1947, before the General Military Government Court in the Dachau internment camp. Since the language of the court was English, interpreters had to translate into English and German between the court and the defendants. After reading out the indictment, the defendants all pleaded "not guilty". The defendants were charged with neglecting, mistreating and killing the detainees. Some of the defendants were charged with crimes related to death marches or as part of the “evacuation” of the camp. The former camp doctor Heinrich Schmidt was accused of neglecting the inmates, who therefore died of hunger, exhaustion and illness. The former head of the protective custody camp, Hans Möser, was given the main responsibility for the inhumane living conditions in the camp. The four prison functionaries were accused of mistreating and sometimes killing prisoners. The civilian Georg Rickhey, as the former general director of Mittelwerk GmbH, was supposed to be responsible for the catastrophic working conditions.

At the request of the prosecution representatives, the accused Albin Sawatzki , Otto Brenneis , Hans Joachim Ritz and Stefan Palko were struck off the list of accused in the Nordhausen trial on the first day of the hearing.

Defense attorney Poullada submitted several unsuccessful motions during the trial, for example to review the jurisdiction of the military tribunal for the Dora trial. Poullada requested the deletion of the addition “and other non-German nationals” in the indictment, justifying this by stating that American military courts could not be responsible for prosecuting war crimes committed by Germans against citizens of the states allied with the German Reich . This application was not granted, since the court stated that otherwise crimes against non-German victims would go unpunished. Furthermore, during the proceedings, he repeatedly requested the removal of the legal institution of common design from the indictment, since, in his opinion, in the previous Dachau concentration camp proceedings , the verdict was not based on common design , but on individually verifiable crimes. This application was also rejected by the court.

In his opening speech, the main prosecutor Berman stated that the Mittelbau-Dora concentration camp not only served the purpose of intensifying the production of the German armaments industry by means of forced labor for concentration camp prisoners, but that the killing of concentration camp prisoners according to the motto extermination through labor became the priority Goal. Berman carried out the war crimes presented at the indictment reading and placed them in direct connection with a camp operation geared towards extermination. According to his argument, therefore, all of the accused were guilty of (attempted) mass murder .

This was followed by evidence , in which the prosecutors had to prove the criminal nature of the camp operations in the Mittelbau-Dora concentration camp: on the one hand, by establishing the responsibilities of individual defendants within this system and, on the other hand, by proving that they had committed or participated in acts of excess. In addition to the living and working conditions in the camp, the prosecution also included the death marches in the evidence. The death marches complex was dealt with primarily with the Gardelegen massacre. During the trial, the prosecution called on over 70 concentration camp survivors as witnesses for their evidence, who, like the witnesses , could be cross-examined . The witnesses also reported on the catastrophic conditions in the camp, in particular the inadequate nutrition and clothing, poor hygiene and poor medical care, as well as the imposition of camp penalties.

The statements of the witnesses about the complex forced labor were essentially descriptions of the working and living conditions during the construction phase of the camp in the winter of 1943/1944. This construction phase, also known as “Hell of Dora”, was characterized by exhausting forced labor in the tunneling and in the expansion of the Kohnstein to an underground rocket factory. A second focus was on statements about rocket assembly in the Mittelwerk, where concentration camp prisoners had to assemble the “ retaliatory weapons ” under agitation and beatings . In this context, executions of concentration camp prisoners for alleged sabotage were also described.

"We were meant to die."

Of the 19 defendants, 13 made use of their right to testify on their own behalf; the others referred to their interrogation protocols before the court. The defendants played down the crimes, pleaded imperative to order , kept silent or denied having been at the scene at the time of the crime. The defense provided 65 witnesses to exonerate during the trial, and the military tribunal also had nine written statements to exonerate the defendants.

The camp doctor Schmidt said the following about the living conditions in the Boelckekaserne satellite camp, which about half of the concentration camp prisoners captured there did not survive:

“Back then in March 1945 the weather was very sunny and warm during the day. Most of the inmates housed in blocks 6 and 7 lay on the south side of the hall wall all day and sunbathed. "

When it came to the subject of forced labor, Georg Rickhey, who was the only representative of Mittelwerk GmbH to stand trial, was at the center of the process. Rickhey was accused of having been responsible for the catastrophic working conditions in the camp, of having cooperated closely with the SS and Gestapo and of having attended executions. Proof of these war crimes was important insofar as Rickey - unlike other defendants - could not be held responsible for the catastrophic living conditions in the concentration camp or the conduct of death marches. In the trial itself, the prosecution referred to Mittelwerk GmbH's involvement in the forced labor involved in underground rocket production ( V1 and V2 rockets ). Rickhey was relieved by former employees and the written interrogation protocols of his engineering colleagues, only the interrogation protocol of a former engineer at Mittelwerk GmbH incriminated him. The witnesses summoned by the prosecution were only able to provide imprecise information about Rickhey's activities and responsibilities in this regard, since, as a rule, they had not seen him personally in the warehouse. Also, there was no written evidence of Rickhey's guilt; Only after the end of the trial were documents found that demonstrate Rickhey's share of responsibility for the inhumane working conditions of the middle class inmates. Rickhey testified on his own behalf and shifted the entire responsibility for the inhumane conditions of forced labor to the engineer Sawatzki, who died in American internment. He also pointed to his work for the American research on the base of the US Air Force (USAF) in Wright Field out.

In his closing argument, Prosecutor Berman called for the death penalty for all of the defendants, since under the Common Design they would all be considered mass murderers if interpreted consistently.

As in its opening statement, the defense also denied in its closing statement the allegations made by the prosecution against the defendants. The defense also insisted again on the failure to apply the legal institution Common Design and demanded that the court only take into account individually proven crimes when determining the sentence. Poullada appealed to the military tribunal to apply the high "standards of Anglo-American jurisprudence" when reaching a verdict and to acquit the defendants if the evidence is not unequivocal. According to his understanding, the defendants should not be judged differently than American citizens in court. The defense therefore demanded an acquittal for Rickhey, as the allegations against him had all been invalidated.

The military tribunal, through its chairman, pronounced the verdicts on December 24, 1947, and the corresponding sentences on December 30, 1947 for convictions. In addition to a death penalty , seven life and seven temporary sentences were imposed. Four defendants were acquitted, including Rickhey. The military tribunal did not give any reasons for the judgment, as this was not intended.

The 19 judgments in detail

The 19 judgments are as follows:

| Surname | rank | function | judgment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Möser | SS-Obersturmführer | Protective custody camp leader in Dora | Death sentence, executed November 26, 1948 |

| Brauny | SS-Hauptscharführer | Camp manager of the subcamp Rottleberode , report and command leader in Dora | lifelong prison sentence |

| Simon | SS-Oberscharführer | Labor leader | lifelong prison sentence |

| Brinkmann | SS-Hauptscharführer | Report leader in Dora, protective custody camp leader in the Ellrich-Juliushütte satellite camp | lifelong prison sentence |

| Buhring | SS-Stabsscharführer | Head of the bunker | lifelong prison sentence |

| Jacobi | SS-Hauptscharführer | Head of the carpentry team in Dora | lifelong prison sentence |

| Kilian | Kapo | Executioner in Dora | lifelong prison sentence |

| king | SS-Hauptscharführer | Report leader in Dora, responsible for the vehicle fleet | lifelong prison sentence |

| Zwiener | Kapo | Camp elder in Dora, clerk in the field of labor deployment | 25 years imprisonment |

| Andrä | SS-Hauptscharführer | Head of the post office in Dora | 20 years imprisonment |

| Walenta | Kapo | Camp elder in the Ellrich-Juliushütte subcamp, overseer in the bunker of the Dora camp | 20 years imprisonment |

| Helbig | SS-Oberscharführer | Head of the clothing store in Dora | 20 years imprisonment, later reduced to 10 years imprisonment |

| Detmers | SS-Obersturmführer | Adjutant to the camp commandant | 7 years imprisonment |

| Ulbricht | Kapo | Office of the subcamp Rottleberode | 5 years imprisonment |

| Maischein | SS Rottenführer | SS medical service grade in the Rottleberode subcamp | 5 years imprisonment |

| Rickhey | civilian | General director of Mittelwerke GmbH | acquittal |

| Schmidt | SS-Hauptsturmführer | Camp doctor in the Boelcke barracks subcamp | acquittal |

| Heinrich | SS-Obersturmführer | Adjutant to the camp commandant | acquittal |

| Foxhole | SS-Hauptscharführer | Deputy warehouse manager of the Mittelbauer satellite camp Harzungen | acquittal |

- ↑ Before the verdict was announced, the military tribunal knew that Detmers had already been sentenced to 15 years imprisonment in January 1947 in a subsidiary trial (Case No. 000-50-2-23 US vs. Alex Piorkowski et al) to the Dachau main trial. This sentence was reduced to five years in prison following a review process. According to the ruling in the Dachau Dora trial, both sentences should be served at the same time.

Review process

After a review process concluded on April 23, 1948 by the competent authority at the Deputy Judge Advocate for War Crimes , the judgments made in the Dachau Dora trial were confirmed with one exception: for the convicted Helbig, a reduction of the prison sentence from twenty to ten years was recommended . In a second review, the War Crimes Board of Review agreed with all the recommendations of the first review body. The Military Governor of the American Occupation Zone, Lucius D. Clay, upheld all judgments as recommended in the review process. They came into force on June 25, 1948.

Side processes

During the Dachau Dora Trial, from the end of October 1947 to mid-December 1947, five ancillary trials took place against five defendants, including one prisoner functionary. These processes, known as short-term proceedings , lasted one day in three cases and two or nine days in each case. A total of 14 ancillary proceedings to the main proceedings were planned, of which nine did not take place due to a lack of witnesses and evidence. Also, the method Case No. 000-Nordhausen-4 was no longer initiated for these reasons.

The five proceedings and judgments in detail

| Procedure | Defendant | rank | function | judgment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case No. 000-Nordhausen-1 | Mikhail Grebinsky | SS man, Romanian | Use in Dora central building | acquittal |

| Case No. 000-Nordhausen-2 | Albert Mueller | SS Rottenführer | Use in Dora central building | 25 years in prison, reduced to ten years in prison |

| Case No. 000-Nordhausen-3 | Georg Finkenzeller | Kapo | Use in the quarry command | 2 years imprisonment |

| Case No. 000-Nordhausen-5 | Philipp Klein | SS squad leader | SS medical rank | 4 years imprisonment |

| Case No. 000-Nordhausen-6 | Stefan Palko | SS Rottenführer | Block leader | 25 years imprisonment reduced to 15 years imprisonment |

Execution of judgments

The convicts were transferred to the Landsberg War Crimes Prison after the verdict was announced . The sentence of death Moser was on 26 November 1948 for the war criminal prison Landsberg hanged . Those sentenced to prison terms were released early from the Landsberg War Crimes Prison, most recently Brinkmann on May 9, 1958. Brinkmann was among the three convicts from the Einsatzgruppen trial among the last four prisoners to be released from Landsberg when the US war crimes program was completed.

Valuations and effects

Only 19 accused were indicted in the main Nordhausen trial and 5 in the secondary proceedings - compared to the 2,400 people in the Dora-Mittelbau concentration camp, a small number of charges. In relation to the other Dachau concentration camp proceedings, the number of accused was also rather small. In the judgments, a tendency towards leniency in the Nordhausen trial became clear: In the Dachau main trial , 36 out of 40 defendants were sentenced to death in the first instance, in the Nordhausen trial only one. In addition, this last Dachau concentration camp procedure was only completed three and a half years after the liberation of the Mittelbau concentration camp. Due to this time gap, the judges could no longer fall back on immediate impressions on site, as they were in the Dachau main proceedings. In addition, witnesses who were needed to identify the accused could often no longer be found.

In contrast to the Buchenwald main trial , which was completed in August 1947, the Dachau Dora trial received little public attention. The headline of the Frankfurter Rundschau on the Dachau Dora Trial, which on August 8, 1947 headlined: “Sensational Trial in Dachau. 19 defendants from the Nordhausen extermination camp - The secret of the manufacture of V weapons in the Dora camp ”. In the southern Harz region, there was hardly any press coverage of the process.

The legal institution of common design was still used in the main Nordhausen proceedings, but no longer as consistently as in the concentration camp proceedings previously carried out as part of the Dachau trials. For example, Heinrich was acquitted as a former adjutant of the camp commandant, while Rudolf Heinrich Suttrop was sentenced to death with the same function in the main Dachau trial . This development is also evident in the subsidiary proceedings to the Nordhausen main proceedings, where the corresponding indictments already contained individual criminal offenses.

Neither Wernher von Braun nor Arthur Rudolph or other important representatives of Mittelwerk GmbH were accused or had to testify personally in court as a witness. Like Rickhey before , they had been brought to the United States as part of Operation Paperclip for rocket research . Rudolph and von Braun only had exonerating interrogation protocols for the accused Rickhey. The American authorities pursued a policy towards the former rocket engineers at Mittelwerk GmbH that varied between the prosecution of war crimes and the skimming of the engineers' expertise.

The denazification lost during the Cold War increasingly important because the Western Allies West Germany wanted to win as allies. After the initial shock of the concentration camp crimes, the German population increasingly showed solidarity with the inmates of the Landsberg war crimes prison. This was also reflected in the gradual softening of the sentences and the early dismissals from Landsberg.

Later legal processing of the crimes in the Mittelbau-Dora concentration camp

Even after the Dachau trials had been concluded, further trials related to violent crimes in the Mittelbau-Dora concentration camp were carried out in the Federal Republic and the GDR . The best-known case was the Essen Dora Trial , which began on November 17, 1967 before the Essen District Court . In this process, the former concentration camp guard Erwin Busta was indicted together with Helmut Bischoff , the former KdS of the restricted area Mittelbau and his former employee Ernst Sander . The subject of the proceedings was the murder of prisoners after failed escapes, as a result of sabotage and during the liquidation of the camp. Furthermore, the murder of 58 alleged resistance fighters and fatal mistreatment during “intensified interrogations” of prisoners following disciplinary offenses were the subject of the proceedings. During the trial, the East German attorney Friedrich Karl Kaul tried to prove their involvement in crimes in the Mittelbau concentration camp by summoning prominent West German witnesses. This was intended to portray the GDR as an anti-fascist state and to show the post-war careers of former Nazi functionaries who were not convicted in West Germany. Bischoff's participation in the proceedings was suspended on May 5, 1970 due to incapacity to stand trial and discontinued in 1974. On May 8, 1970, Busta was sentenced to eight and a half years in prison and Sander to seven and a half years in prison. However, Busta and Sander did not have to serve their sentences due to exemption and reprieve.

Litigation documents

In the spring of 2004, the owner of a recycling company in Kerkrade found documents from the Dachau Dora trial as well as photos of the liberation of the Mittelbau concentration camp and its subcamps while emptying a waste paper container. How the documents got into the waste paper container could no longer be determined. However, these documents could be assigned to the estate of William J. Aalmans, who worked for the prosecution during the Dachau Dora trial. At the beginning of July 2004, the documents were handed over to the Mittelbau-Dora Memorial , where some of them are shown in the permanent exhibition.

source

- Deputy Judge Advocate's Office 7708 War Crimes Group European Command APO 407: United States v. Kurt Andrae et al. Case No. 000-50-37. Review and Recommendations of the Deputy Jugde Advocate for War Crimes , April 1948. ( online PDF file; 14.1 MB)

literature

- Michael Löffelsender: A particularly unique role among concentration camps. The Dachauer Dora trial in 1947. In: Helmut Kramer , Karsten Uhl , Jens-Christian Wagner (eds.): Forced labor under National Socialism and the role of the judiciary - perpetrators, post-war trials and the dispute about compensation payments. Nordhausen 2007, pp. 152-169 ( online PDF file; 1.62 MB).

- Robert Sigel: In the interests of justice. The Dachau war crimes trials 1945-48. Campus, Frankfurt am Main 1992, ISBN 3-593-34641-9 .

- Ute Stiepani: The Dachau Trials and their significance in the context of the Allied prosecution of Nazi crimes. In: Gerd R. Ueberschär : The allied trials against war criminals and soldiers 1943–1952. Fischer, Frankfurt am Main 1999, ISBN 3-596-13589-3 .

- Jens-Christian Wagner : Production of Death: The Mittelbau-Dora Concentration Camp. Wallstein, Göttingen 2001, ISBN 3-89244-439-0 .

- Jens-Christian Wagner (Ed.): Mittelbau-Dora Concentration Camp 1943–1945 Accompanying volume for the permanent exhibition in the Mittelbau-Dora Concentration Camp Memorial. Wallstein, Göttingen 2007, ISBN 978-3-8353-0118-4 .

Web links

- Dachauer Nordhausen procedure (English)

Individual evidence

- ^ Jens-Christian Wagner (ed.): Mittelbau-Dora concentration camp 1943–1945. Göttingen 2007, p. 7.

- ^ Jens-Christian Wagner: Production of death: The Mittelbau-Dora concentration camp. Göttingen 2001, p. 301.

- ↑ Wolfgang Benz , Barbara Distel (ed.): The place of terror . History of the National Socialist Concentration Camps. Volume 7: Niederhagen / Wewelsburg, Lublin-Majdanek, Arbeitsdorf, Herzogenbusch (Vught), Bergen-Belsen, Mittelbau-Dora. CH Beck, Munich 2008, ISBN 978-3-406-52967-2 , p. 333.

- ^ Karola Fings : War, Society and KZ. Himmler's SS construction brigades. Ferdinand Schöningh, Paderborn 2005, ISBN 3-506-71334-5 , p. 274.

- ↑ a b Michael Löffelsender: A particularly unique role among concentration camps. Nordhausen 2007, p. 154.

- ↑ Robert Sigel: In the interests of justice. The Dachau war crimes trials 1945–48. Frankfurt am Main 1992, p. 16 ff.

- ↑ Manfred Overesch : Buchenwald and the GDR - or the search for self-legitimation. 1995, pp. 207ff.

- ↑ Katrin Greiser: The Dachau Buchenwald processes - claim and reality - claim and effect. In: Ludwig Eiber , Robert Sigl (eds.): Dachau Trials - Nazi crimes before American military courts in Dachau 1945–1948. Göttingen 2007, p. 162.

- ^ Jens-Christian Wagner: Production of death: The Mittelbau-Dora concentration camp. Göttingen 2001, p. 567.

- ↑ Ernst Klee : Das Personenlexikon zum Third Reich: Who was what before and after 1945. Frankfurt am Main 2007, p. 24, 158.

- ^ Jens-Christian Wagner: Production of death: The Mittelbau-Dora concentration camp. Göttingen 2001, p. 296f.

- ^ Frank Wiedemann: Everyday life in the Mittelbau-Dora concentration camp. Methods and strategies of inmate survival. Peter Lang - Internationaler Verlag der Wissenschaften, Frankfurt am Main 2010, p. 51.

- ↑ a b c d e f Robert Sigel: In the interests of justice. The Dachau war crimes trials 1945–48. Frankfurt am Main 1992, pp. 16 ff., 99f.

- ↑ a b c Deputy Judge Advocate's Office 7708 War Crimes Group European Command APO 407: United States v. Kurt Andrae et al. Case No. 000-50-37. Review and Recommendations of the Deputy Jugde Advocate for War Crimes , April 1948, pp. 30ff.

- ↑ Michael Löffelsender: A particularly unique role among concentration camps. Nordhausen 2007, p. 154.

- ↑ a b c Michael Löffelsender: A particularly unique role among concentration camps. Nordhausen 2007, p. 155.

- ^ A b Robert Sigel: In the interests of justice. The Dachau war crimes trials 1945–48. Frankfurt am Main 1992, p. 214.

- ↑ a b Michael Löffelsender: A particularly unique role among concentration camps. Nordhausen 2007, p. 152.

- ↑ Robert Sigel: In the interests of justice. The Dachau war crimes trials 1945–48. Frankfurt am Main 1992, p. 96.

- ↑ Deputy Judge Advocate's Office 7708 War Crimes Group European Command APO 407: United States v. Kurt Andrae et al. Case No. 000-50-37. Review and Recommendations of the Deputy Jugde Advocate for War Crimes , April 1948, pp. 2f.

- ↑ a b Michael Löffelsender: A particularly unique role among concentration camps. Nordhausen 2007, p. 158.

- ↑ Robert Sigel: In the interests of justice. The Dachau war crimes trials 1945–48. , Frankfurt am Main 1992, pp. 98f.

- ↑ Michael Löffelsender: A particularly unique role among concentration camps. Nordhausen 2007, p. 157f.

- ↑ a b Michael Löffelsender: A particularly unique role among concentration camps. Nordhausen 2007, p. 159f.

- ^ Jens-Christian Wagner: Production of death: The Mittelbau-Dora concentration camp. Göttingen 2001, p. 26.

- ↑ Michael Löffelsender: A particularly unique role among concentration camps. Nordhausen 2007, p. 160.

- ↑ Quoted from Ulrich Herbert , Karin Orth , Christoph Dieckmann (ed.): The National Socialist Concentration Camps , Volume 1: Development and Structure. Wallstein Verlag, Göttingen 1998, p. 718.

- ↑ a b Michael Löffelsender: A particularly unique role among concentration camps. Nordhausen 2007, p. 164.

- ↑ Quoted from: Jens-Christian Wagner: Production of death: The Mittelbau-Dora concentration camp. Göttingen 2001, p. 496f.

- ^ A b Jens-Christian Wagner: Production of death: The Mittelbau-Dora concentration camp. Göttingen 2001, p. 567f.

- ↑ Michael Löffelsender: A particularly unique role among concentration camps. Nordhausen 2007, p. 163ff.

- ↑ a b c Michael Löffelsender: A particularly unique role among concentration camps. Nordhausen 2007, p. 165.

- ↑ a b c Robert Sigel: In the interests of justice. The Dachau war crimes trials 1945–48. Frankfurt am Main 1992, p. 102.

- ↑ Michael Löffelsender: A particularly unique role among concentration camps. Nordhausen 2007, p. 166.

- ↑ The information in the table relates to: United States of America vs Kurt Andrae et al. - Case 000-50-37 ( Memento of the original from September 25, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. on www1.jur.uva.nl (judicial and Nazi crimes) and Deputy Judge Advocate's Office 7708 War Crimes Group European Command APO 407: United States v. Kurt Andrae et al. Case No. 000-50-37. Review and Recommendations of the Deputy Jugde Advocate for War Crimes , April 1948.

- ↑ Robert Sigel: In the interests of justice. The Dachau war crimes trials 1945–48. Frankfurt am Main 1992, p. 102.

- ^ A b Robert Sigel: In the interests of justice. The Dachau war crimes trials 1945–48. Frankfurt am Main 1992, p. 104.

- ↑ a b Michael Löffelsender: A particularly unique role among concentration camps. Nordhausen 2007, p. 166.

- ↑ List of names of the persons accused in the Dachau trials ( Memento of the original from September 15, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. on www1.jur.uva.nl (judicial and Nazi crimes)

- ↑ Nordhausen Cases on jewishvirtuallibrary.org

- ^ Ernst Klee: Das Personenlexikon zum Third Reich: Who was what before and after 1945. Frankfurt am Main 2007, p. 414.

- ^ Jens-Christian Wagner: Production of death: The Mittelbau-Dora concentration camp. Göttingen 2001, p. 568.

- ↑ Norbert Frei: Politics of the Past. The beginnings of the Federal Republic and the Nazi past . Munich 2003, p. 138.

- ↑ Robert Sigel: In the interests of justice. The Dachau war crimes trials 1945–48. Frankfurt am Main 1992, pp. 103f.

- ^ Jens-Christian Wagner (ed.): Mittelbau-Dora concentration camp 1943–1945. Göttingen 2007, p. 568f.

- ↑ Michael Löffelsender: A particularly unique role among concentration camps. Nordhausen 2007, p. 162.

- ↑ Norbert Frei: Politics of the Past. The beginnings of the Federal Republic and the Nazi past. Munich 2003, ISBN 3-423-30720-X , pp. 133–306.

- ↑ a b Judicial and Nazi crimes - procedural overviews (crime scene KL Dora) ( Memento of the original from February 23, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ A b Andrè Sellier: Forced Labor in the Rocket Tunnel - History of the Dora Camp. Lüneburg 2000, p. 518.

- ^ Jens-Christian Wagner (ed.): Mittelbau-Dora concentration camp 1943–1945. Göttingen 2007, p. 155.

- ↑ George Wamhof: historical politics and Nazi criminal. The Essen Dora Trial (1967–1970) in the German-German system conflict . In: Helmut Kramer, Karsten Uhl, Jens-Christian Wagner (eds.): Forced labor under National Socialism and the role of the judiciary - perpetration, post-war trials and the dispute over compensation payments . Nordhausen 2007, p. 190.

- ↑ From the garbage to the memorial. In: Neue Nordhäuser Zeitung online from July 7, 2004