Amniotic fluid embolism

| Classification according to ICD-10 | |

|---|---|

| O88.1 | Amniotic fluid embolism |

| ICD-10 online (WHO version 2019) | |

An amniotic fluid embolism is a special form of an embolism in which amniotic fluid , including its solid parts, enters the maternal circulation via the uterus during delivery . This obstructs pulmonary arterioles or capillaries and affects the coagulation system. It is a rare but dangerous emergency situation feared by obstetricians because it is usually dramatic and often fatal. Surviving mothers and children often suffer brain damage .

The amniotic fluid embolism is synonymous as Obstetric shock syndrome , Amnioninfusionssyndrom ( English Amniotic fluid embolism - AFE) anaphylactic pregnancy syndrome ( english anaphylactoid syndrome of pregnancy ) or Steiner Lushbaugh syndrome called. The processes were first described by J. Ricardo Meyer in 1926 and defined as an independent disease in 1941 by Steiner and Lushbaugh .

To date, an amniotic fluid embolism is unpredictable and difficult to diagnose and treat. No preventive measures are known.

Occurrence

The information in the medical literature on the frequency ( incidence ) of amniotic fluid embolism fluctuates considerably and is given as one disease per 800 to 80,000 births . In industrialized countries, an incidence of 1 in 20,000 to 80,000 births is assumed. The different information on the incidence is due to the fact that it is difficult to make a reliable diagnosis. In the UK , amniotic fluid embolism is the fourth leading cause of maternal death, with a rate of 0.77 per 100,000 deliveries. In Australia , it was recorded as the cause of death in 0.9 out of 100,000 deliveries between 1964 and 1990. In France this was 1.5 in every 100,000 deliveries from 1996 to 1998 and 0.5 in 1999 to 2001.

25 to 34% of mothers die within the first hour. Only 16 to 20% of mothers ultimately survive such an event. 70% of all amniotic fluid embolisms occur during childbirth, 11% after vaginal delivery and 19% during a caesarean section after the child has developed. Infant mortality is up to 50% in amniotic fluid embolisms that occur before or during birth.

Although amniotic fluid embolism almost always occurs during or shortly after birth, there are also individual reports of amniotic fluid embolism in the first and second trimester of pregnancy . The disease began there in connection with an invasive procedure in the case of restrained miscarriage or induction of abortion , but has not yet been observed during scraping due to a miscarriage . Several cases of amniotic fluid embolism have also been described with the rarely performed infusion of physiological saline solution into the amniotic cavity for meconium aspiration prophylaxis and with an amniotic fluid puncture. Blunt force against the abdomen ( abdominal trauma ) can also lead to amniotic fluid embolism.

Disease emergence

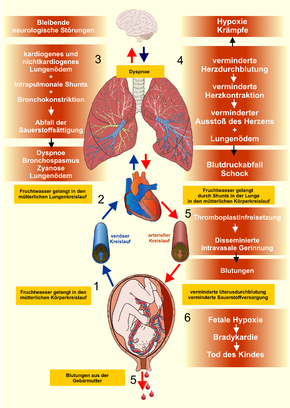

The pathophysiology of amniotic fluid embolism is still not fully understood. On the one hand, it is a special form of pulmonary embolism , which is triggered when components of the amniotic fluid come into contact with the maternal bloodstream. There is often a temporal connection to the rupture of the bladder , so that this is viewed as a possible cause. On the other hand, a whole complex of reactions is triggered that go far beyond an embolism.

The amniotic fluid penetrates into the venous system of the mother via the opened bed of the placenta (placental attachment point), via an injury to the venous plexus of the uterus or via injuries to vessels in the cervix . From there it reaches the pulmonary arteries via the right side of the heart or via shunts in the heart or in the lungs to the left side of the heart and then into the body circulation .

The mechanisms involved in the development of amniotic fluid embolism are only partially known. The explanations of the processes are based on clinical observations and partly on animal experiments .

- At first it was believed that the solid amniotic fluid components, such as vernix flakes , lanugo hairs , meconium or cell exfoliation, trigger the process by obstruction of the vessels in the lungs (solid embolism). It is now known from animal experiments that contact with amniotic fluid components, through the release of prostaglandins and biogenic amines , also leads to a pronounced narrowing of the pulmonary vessels, which in turn increases the blood pressure in the arterial pulmonary circulation . This leads to a right heart overload (acute cor pulmonale ), a sudden drop in the filling pressure of the left heart, resulting in a left heart overload and subsequently to a reduction in the oxygen supply to the body. In many cases, this reaction leads to cardiogenic (heart-related) shock and acute cardiac death .

- A second mechanism is the initiation of generalized coagulation ( disseminated intravascular coagulation ) by components of the amniotic fluid, whereby the meconium in particular seems to play a decisive role. The blood clots that form anywhere in the maternal circulation , in conjunction with the inadequate circulation ( heart failure ), can cause additional embolisms. In connection with the lack of oxygen, liver and kidney failure , seizures and coma can occur. In addition, the massive coagulation reaction leads to the consumption of coagulation factors ( consumption coagulopathy ), which are then no longer available for other coagulation processes necessary during birth, such as the closure of the birth wounds and the placental attachment point. This leads to considerable blood loss and even hemorrhagic shock .

- A third mechanism is triggered by the antigenic activity of the amniotic fluid in the sense of an anaphylactic reaction . In the maternal circulation, fetal antigens lead to an immune response with the release of the body's own messenger substances (endogenous mediators), which can cause dramatic circulatory reactions. In the literature it has therefore also been suggested to replace the term “amniotic fluid embolism” with “anaphylactoid syndrome of pregnancy”.

However, not every contact of amniotic fluid and its components with the maternal circulation leads to an amniotic fluid embolism. In 1961, trophoblast tissue was detected in the lungs in almost half of 220 maternal deaths , but less than 1% of women had shown clinical evidence of amniotic fluid embolism. Usually only small amounts of amniotic fluid (1 to 2 ml) enter the maternal circulation during childbirth. In order to set the chain of reactions in motion, a large amount of amniotic fluid has to pass into the maternal circulation.

Risk factors

As predisposing factors for the disease are considered uterine rupture , birth injuries (as high vaginal tear, Zervixriss z.), Manual removal of the placenta , a placental abruption , vaginal operative deliveries , increased intrauterine pressure (z. B. in a child, multiple births or large Polyhydramnios ), the Kristellerhilfe (due to the stamp effect) and an overdose of contractions. However, in some studies there was no relationship to fetal macrosomia and to an overdose of the contraceptive oxytocin .

Canadian researchers also found a higher incidence of amniotic fluid embolism associated with gestational diabetes , preeclampsia , advanced motherhood , caesarean section, and induction of labor . 88% of those affected are multiparous. In 41% of patients with an amniotic fluid embolism, anamnestic evidence of allergies or atopy is found . In addition, amniotic fluid embolism was observed more frequently in connection with male fetuses.

Although the predisposing factors increase the risk of amniotic fluid embolism, they cannot be regarded as the cause. The clinical picture is considered unpredictable. No preventive measures are known.

Symptoms and course

Clinical Criteria

The national amniotic fluid embolism (AFE) registries in the USA and Great Britain established clinical criteria that allow a suspected diagnosis of amniotic fluid embolism:

- acute drop in blood pressure or cardiac arrest

- acute hypoxia ( dyspnoea , cyanosis, or respiratory failure)

- Coagulation disorder (laboratory evidence of disseminated intravascular coagulation) or severe bleeding

- Symptoms start during labor or up to 30 minutes after the baby is born

- no other clinical signs or explanations for the symptoms

Phases

Amniotic fluid embolism has several stages, each of which is potentially fatal.

As a sign of difficulty breathing, chills, anxiety, photophobia, anxiety, can sensory disturbances occur the finger, nausea and vomiting. The interval between these first signs and the acute symptoms can be very short, but can also be up to 4 hours.

In the early stages, within the first few minutes, the patients show shortness of breath with cyanosis and seizures out of total well-being . There are also signs of shock . Contrary to previous assumptions, chest pain occurs in over half of women. Violent labor up to uterine tetany exist in about a quarter of women.

If the woman survives this first phase, bleeding occurs in the second phase with a latency period of 0.5 to 12 hours, which is the result of generalized coagulation with consumption coagulopathy . Due to the large wound areas after the placenta has been detached, there is a risk of dying from hemorrhagic shock .

In the late stage, a respiratory distress syndrome with pulmonary edema develops . There is a hyper fibrinolysis and as a result of the shock may be a multi-organ failure . Since the second and third phases flow into each other, they are often combined and the entire process is referred to as biphasic.

Childish reactions

The unborn child's heart rate changes due to the reduced oxygen supply. These manifest themselves as abnormalities in the CTG , such as tachycardia , late decelerations , a decrease in bandwidth, prolonged variable decelerations and bradycardia . However, cases with an unremarkable CTG despite the existing fetal threat have also been described. If the oxygen supply is not improved quickly or an emergency caesarean section is not carried out, the child dies after a short time ( intrauterine fetal death ).

Diagnosis

The clinical diagnosis of amniotic fluid embolism is a diagnosis of exclusion. Due to the highly acute events, it must be asked quickly so that appropriate measures can be initiated if there is any suspicion. Different diseases must be taken into account in the differential diagnosis.

Laboratory tests show signs of consumption coagulopathy:

- Thrombocytopenia

- Hypofibrinogenemia (lack of fibrinogen )

- decreased prothrombin time

- extended partial thrombin time

- Detection of D-Dimers

The ECG initially shows tachycardia and changes in the ST segment, later signs of right heart strain. The oxygen saturation in the blood is reduced. Even detection of fetal components in the blood from the right ventricle can only support the diagnosis, but not prove it.

| Lung problems | Drop in blood pressure and symptoms of shock | Coagulation disorders and acute causes of bleeding | Neurological and other disorders associated with convulsions |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Pulmonary embolism ( thrombotic , air , fat ) Pulmonary edema Anesthetic incident Aspiration |

septic shock hemorrhagic shock myocardial infarction anaphylactic reaction cardiac arrhythmia |

Disseminated intravascular coagulation. Premature placental detachment. Uterine rupture. Uterine atony |

Eclampsia Epilepsy Cerebrovascular Insufficiency Hypoglycemia |

An amniotic fluid embolism can only be reliably diagnosed post mortem as part of an autopsy by histologically detecting amniotic fluid or corpuscular parts in the capillaries of the lungs . This often also serves to rule out suspected medical errors by doctors and midwives.

therapy

A specific or causal treatment of the amniotic fluid embolism is not possible. If an amniotic fluid embolism is suspected, the patient is treated symptomatically, but intensively . The focus here is on stabilizing the patient's condition.

Endotracheal intubation with artificial ventilation is almost always necessary. By infusion is (for volume replacement), preferably under control of the central venous pressure of the blood pressure drop counteracted. Right heart failure is counteracted by administering drugs that widen the pulmonary circulation . To treat the immunological components, it makes sense to give glucocorticoids .

If the maternal condition can be stabilized, a quick vaginal delivery is possible. If there is no improvement within 4 to 5 minutes, an emergency caesarean section is indicated due to the impending death of the child, even if the mother appears to be dying (peri-mortem caesarean section) . This also improves the chances of cardiopulmonary resuscitation for the mother.

After the child is born, oxytocin must also be given by infusion in combination with ergot alkaloids such as methylergometrine to prevent uterine atony with massive vaginal bleeding. These agents encourage the uterus to contract, thereby reducing bleeding. The administration of prostaglandins must be avoided, as these can potentially have vasoconstrictive effects on the pulmonary vessels.

If the patient survives the first phase, the patient should be monitored by intensive care. For the treatment of clotting disorder, administration of antifibrinolytic agents and a treatment with fresh frozen plasma ( fresh frozen plasma , FFP) and as a last resort, with continuing circulation and platelet counts below 50,000 / ul, the transfusion of platelet concentrates possible. The blood loss is compensated for with red cell concentrates . Attempts at treatment with cryoprecipitates and recombinant factor VII (rFVIIa) have also been undertaken. Successful uterine artery embolizations to treat excessive bleeding from the uterus have also been reported.

forecast

The prognosis for amniotic fluid embolism is poor. It causes high maternal and infant mortality. 11% of the surviving women and 61% of the surviving children develop permanent neurological damage. Especially after amniotic fluid embolism with amniotic fluid containing mekonium, neurological abnormalities with brain anatomical correlates were more frequently detectable in surviving women . The prognosis also depends on rapid treatment. A peri-mortem caesarean section after 4 to 5 minutes of unsuccessful resuscitation improves the chances of resuscitation for the woman and the chances of survival for the child.

Due to the small number of cases, the risk of a new amniotic fluid embolism in a subsequent pregnancy cannot be assessed. However, pregnancies without complications have been reported. The recommendation of a primary caesarean section to avoid labor is controversial.

history

In 1893, the German pathologist Georg Schmorl reported for the first time on fetal cells in the maternal lungs that he found in autopsies of 17 women who had died after eclampsia . He saw this as a possible cause of eclampsia.

An amniotic fluid embolism was described by J. Ricardo Meyer in Brazil for the first time as early as 1926, but in 1927 MR Warden published the results of his animal experiments with intravenous injection of amniotic fluid, in which he also saw a possible cause of the eclampsia.

It was not until 1941 that the Americans Paul E. Steiner and Clarence Lushbaugh defined amniotic fluid embolism as an independent clinical picture and in 1949 it was described in more detail as obstetric shock syndrome . It was therefore temporarily called Steiner-Lushbaugh syndrome. designated.

In 1961, British pathologists Attwood and Park found trophoblast tissue in the lungs of almost half of 220 maternal deaths , although less than 1% of women had provided clinical evidence of amniotic fluid embolism. Therefore, this was ruled out as the sole cause of the clinical picture. Even a connection to amniotic fluid embolism is questionable. During pregnancy, fetal cells inevitably enter the maternal circulation. This phenomenon is considered physiological . However, an embolism with partial occlusion of the pulmonary circulation is not to be regarded as normal and appears to be more frequently associated with pathological changes in the placenta, such as placenta accreta or placenta previa , and manipulations of the uterus.

Since the typical symptoms of anaphylaxis predominated in some examinations of an amniotic fluid embolism , the clinical picture is also known as anaphylactoid syndrome of pregnancy (anaphylactic pregnancy syndrome ).

In the US and UK , special registers have been created to record cases of amniotic fluid embolism. The US National AFE Registry was founded in 1998 by Steven L. Clark, a gynecologist at the University of Utah School of Medicine. Derek J. Tuffnell, Director of the Women's Clinic at Bradford Royal Infirmary , initiated the UKOSS Amniotic fluid embolism register . It has been part of the UK Obstetric Surveillance System (UKOSS) of the University of Oxford's National Perinatal Epidemiology Unit, which has existed since 1978, for the investigation of rare diseases in pregnancy and is supported by the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (RCOG).

literature

German speaking

- Joachim Wolfram Dudenhausen , Hermann PG Schneider , Gunther Bastert : Gynecology and obstetrics. Walter de Gruyter, 2002, ISBN 3-11-016562-7 , pp. 638-640. in Google Book Search .

- Wolfgang Distler, Axel Riehn: Emergencies in gynecology and obstetrics. Springer, 2006, ISBN 3-540-25666-0 , Chapter 5.13 in the Google Book Search .

- Alexander Strauss: Obstetrics Basics. Springer, 2006, ISBN 3-540-25668-7 , p. 70. in the Google book search .

- Maritta Kühnert: Emergency situations in obstetrics. Walter de Gruyter, 2009, ISBN 978-3-11-021378-2 , pp. 86-89. in Google Book Search .

- Jürgen Nieder, Kerstin Meybohm: Memorix for midwives. Georg Thieme Verlag, 2001, ISBN 3-7773-1422-6 , p. 240. in the Google book search .

- Christine Mändle, Sonja Opitz-Kreuter: The midwifery textbook of practical obstetrics. Schattauer Verlag, 2007, ISBN 978-3-7945-1765-7 , pp. 472-474. in Google Book Search .

- Werner H. Rath, Stefan Hofer, Inga Sinicina: Amniotic fluid embolism - an interdisciplinary challenge: epidemiology, diagnostics and therapy. In: Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2014, 111 (8), pp. 126–132, doi: 10.3238 / arztebl.2014.0126

- Werner H. Rath: Amniotic fluid embolism and cardiac arrest. Frauenarzt 58 (2017), 296–301

English speaking

- Hung N. Winn, RH Petrie: Amniotic fluid embolism. In: Hung N. Winn, John C. Hobbins: Clinical maternal-fetal medicine. Taylor & Francis, 2000, ISBN 1-85070-798-7 , Chapter 11 in Google Book Search .

- Maureen Boyle: Amniotic fluid embolism. In: Maureen Boyle: Emergencies around childbirth: a handbook for midwives. Radcliffe Publishing, 2002, ISBN 1-85775-568-5 , Chapter 7 in Google Book Search .

- Charlotte Howell, Kate Grady, Charles Cox: Amniotic fluid embolism. In: Managing Obstetric Emergencies and Trauma: The MOET Course Manual. RCOG , 2007, ISBN 978-1-904752-21-9 , Chapter 5 in Google Book Search .

- Steven L. Clark: Managing obstetric emergencies: Anaphylactoid syndrome of pregnancy (aka AFE). Contemporary OB / GYN, July 2018, online

Web links

- Lisa E. Moore: Amniotic Fluid Embolism. on eMedicine.com

- Histological picture of the University of Utah

- Amniotic Fluid Embolism Foundation ( afesupport.org )

Individual evidence

- ^ A b c Alfredo Gei, Gary DV Hankins: Amniotic fluid embolus: An update. In: Contemp Ob / Gyn. , 45, 2000, pp. 53-66, online .

- ↑ A. Peitsidou, P. Peitsidis, V. Tsekoura and a .: Amniotic fluid embolism managed with success during labor: report of a severe clinical case and review of literature. In: Arch Gynecol Obstet. 277 (2008), pp. 271-275, doi: 10.1007 / s00404-007-0489-z .

- ↑ Ludwig Spätling: Amniotic fluid embolism. In: The gynecologist . 30: 757-761 (1997).

- ↑ a b D. J. Tuffnell, H. Johnson: Amniotic fluid embolism: the UK register. In: Hosp Med. 61 (2000), pp. 532-534, PMID 11045220 .

- ↑ a b c A. Burrows, SK Khoo: The amniotic fluid embolism syndrome: 10 years' experience at a major teaching hospital. In: Aust New Zealand J Obstet Gynecol. , 35, 1995, pp. 245-250, doi: 10.1111 / j.1479-828X.1995.tb01973.x .

- ↑ Rapport du Comité national d'experts sur la mortalité maternelle. (CNEMM) (Report of the National Expert Commission on Maternal Mortality ). December 2006, p. 35, invs.sante.fr (PDF; 475 kB).

- ↑ a b c d e f g Steven L. Clark, G. Hankins, D. Dudley et al. a .: Amniotic fluid embolism: analysis of the national registry. In: Am J Obstet Gynecol. , 172, 1995, pp. 1158-1167, PMID 7726251

- ↑ a b R. Mander, G. Smith: Saving mothers' lives (formerly Why mothers die): Reviewing maternal deaths to make motherhood safer 2003-2005. In: Midwifery , 24, 2008, pp. 8-12, PMID 18282645 .

- ^ R. Guidotti, D. Grimes, W. Cates: Fatal amniotic fluid embolism during legally induced abortion, United States, 1972 to 1978. In: Am J Obstet Gynecol. , 141, 1981, pp. 257-261, PMID 7282806 .

- ↑ G. Dorairajan, S. Soundararaghavan: Maternal death after intrapartum saline amnioinfusion - report of two cases. In: BJOG , 112, 2005, pp. 1331-1333, doi: 10.1111 / j.1471-0528.2005.00708.x .

- ↑ TH Hasaart, GG Possessed: Amniotic fluid embolism after transabdominal amniocentesis. In: Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 16 (1983), pp. 25-30, PMID 6628816 .

- ^ J Dodgson, J. Martin, J. Boswell, HB Goodall, R. Smith: Probable amniotic fluid embolism precipitated by amniocentesis and treated by exchange transfusion. In: British medical journal (Clinical research ed.). Volume 294, Number 6583, May 1987, pp. 1322-1323, PMID 3109636 , PMC 1246486 (free full text).

- ↑ C. Ellingsen, T. Eggebo, K. Lexow: Amniotic fluid embolism after blunt abdominal trauma. In: Resuscitation. 75 (2007), pp. 180-183, doi: 10.1016 / j.resuscitation.2007.02.010 .

- ↑ a b c d e f g R. Lachmann, G. Kamin, F. Bender, M. Jaekel, W. Distler: Amniotic fluid embolism. Overview and presentation of cases with a good outcome. In: Gynecologist . 41 (2008), pp. 420-426, doi: 10.1007 / s00129-008-2136-6 .

- ↑ a b c d e Joachim Wolfram Dudenhausen , Hermann PG Schneider , Gunther Bastert : gynecology and obstetrics. Walter de Gruyter, 2002, ISBN 3-11-016562-7 , pp. 638-640. in Google Book Search .

- ↑ Carlo Bouchè, M. Casarotto, U. Wiesenfeld, R. Bussani, R. Addobati, P. Bogatti: Pathophysiology of Amniotic Fluid Embolism: new considerations and remarks for syndrome diagnosis. .

- ↑ Sven Hildebrandt: Amniotic fluid embolism - a rare but severe obstetric emergency. In: midwife. 18 (2005), pp. 153-155, doi: 10.1055 / s-2005-918610 .

- ↑ a b H. D. Attwood, WW Park: Embolism to the lungs by trophoblast. In: BJOG. 68 (1961), pp. 611-617, doi: 10.1111 / j.1471-0528.1961.tb02778.x .

- ↑ Michael S. Kramer, Jocelyn Rouleau, Thomas F. Baskett, KS Joseph: Amniotic-fluid embolism and medical induction of labor: a retrospective, population-based cohort study. In: Lancet. 368 (2006), pp. 1444-1448, doi: 10.1016 / S0140-6736 (06) 69607-4 .

- ↑ Marie R. Baldisseri: Amniotic fluid embolism syndrome. UpToDate V.18.3 .

- ↑ a b c d e f g M. Kretzschmar, D.-M. Zahm, K. Remmler, L. Pfeiffer, L. Victor, W. Schirrmeister: “Anaphylactoid syndrome of pregnancy.” Pathophysiological and therapeutic aspects of amniotic fluid embolism (“anaphylactoid syndrome of pregnancy”) based on a case report with a fatal outcome. In: Anaesthesist , 52, 2003, pp. 419-426, doi: 10.1007 / s00101-003-0482-2 .

- ↑ DJ Tuffnell: Managing amniotic fluid embolism. In: OBG Management. 15 (2003), pp. 36-51, online (PDF; 78 kB).

- ↑ a b A. Rudra, S. Chatterjee, S. Sengupta, B. Nandi, J. Mitra: Amniotic fluid embolism. In: Indian J Crit Care Med. 13 (2009), pp. 129-135, PMID 20040809 , doi: 10.4103 / 0972-5229.58537 .

- ↑ Katherine J. Perozzi, Nadine C. Englert: Amniotic fluid embolism. To Obstetric Emergency. In: Critical Care Nurse. 24 (2004), pp. 54-61, online .

- ↑ I. Sinicina, H. Pankratz, K. Bise, E. Matevossian: Forensic aspects of post-mortem histological detection of amniotic fluid embolism. In: International Journal of Legal Medicine. 124 (2010), pp. 55-62, doi: 10.1007 / s00414-009-0351-x .

- ↑ Steven L. Clark: Amniotic Fluid Embolism. In: Clin Obstet Gynecol. 53 (2010), pp. 322-328, doi: 10.1097 / GRF.0b013e3181e0ead2 .

- ↑ H. Vehreschild: "Perimortale" cesarean section in amniotic fluid embolism. In: Gynecological Practice. 24 (2000), pp. 15-23.

- ^ Y. Lim, CC Loo, V. Chia, W. Fun: Recombinant factor VIIa after amniotic fluid embolism and disseminated intravascular coagulopathy. In: Int J Gynaecol Obstet. , 87, 2004, pp. 178-179, PMID 15491576 , doi: 10.1016 / j.ijgo.2004.08.007 .

- ↑ Sharon Davies: Amniotic fluid embolus: a review of the literature. In: Can J Anaesth. , 48, 2001, pp. 88-98, PMID 11212056 , doi: 10.1007 / BF03019822 , springer.com (PDF; 84 kB).

- ^ E. Goldszmidt, S. Davies: Two cases of hemorrhage secondary to amniotic fluid embolus managed with uterine artery embolization. In: Can J Anaesth. , 50, 2003, pp. 917-921, PMID 14617589 , doi: 10.1007 / BF03018739 .

- ↑ MS Kramer, J. Rouleau, S. Liu, S. Bartholomew, KS Joseph: Amniotic fluid embolism: incidence, risk factors, and impact on perinatal outcome. In: BJOG , 119, 2012, pp. 874-879, doi: 10.1111 / j.1471-0528.2012.03323.x , PMID 22530987

- ^ Vern L. Katz, DJ Dotters, W. Droegemueller: Perimortem cesarean delivery. In: Obstet Gynecol. 68: 571-576 (1986) PMID 3528956 .

- ↑ Vern L. Katz, Keith Balderston, Melissa DeFreest: Perimortem cesarean delivery: Were our assumptions correct? In: Am J Obstet Gynecol. , 192, 2005, pp. 1916-1921, doi: 10.1016 / j.ajog.2005.02.038 .

- ↑ Lisa E. Moore: Amniotic Fluid Embolism . eMedicine.com

- ↑ Georg Schmorl: Pathological-anatomical studies on puerperal eclampsia. FCW Vogel publishing house, Leipzig 1893.

- ↑ J. Ricardo Meyer: embolia pulmonary amniocaseosa. In: Brasil-Medico. 2, pp. 301-303 (1926).

- ↑ MR Warden: Amniotic fluid as possible factor in etiology of eclampsia. In: Amer J Obstet Gynec. , 14, 1927, p. 292.

- ^ Paul E. Steiner, Clarence Lushbaugh , Maternal pulmonary embolism by amniotic fluid. In: JAMA , 117, 1941, pp. 1245-1254, doi: 10.1001 / jama.1941.02820410023008 .

- ↑ Paul E. Steiner, Clarence Lushbaugh , HA Frank: Fatal obstetric shock for pulmonary emboli of amniotic fluid. In: Am J Obstet Gynecol. 58: 802-805 (1949).

- ↑ GM Rendina: Amniotic fluid embolus: (Steiner-Lushbaugh syndrome). In: Riv Ostet Ginecol Prat. , 40, 1958, pp. 945-958, PMID 13592081 .

- ↑ Sean Kane: Historical Perspective of Amniotic Fluid Embolism. In: Int Anesthesiol Clin. , 43, 2005, pp. 99-108, PMID 16189399 .

- ↑ Julia Franzen: Pulmonary syncytiotrophoblast embolism: a physiological phenomenon? Dissertation . Ludwig Maximilians University Munich 2010, uni-muenchen.de (PDF; 3.6 MB)

- ↑ Amniotic Fluid Embolism Register of the UK Obstetric Surveillance System (UKOSS)

- ^ World first for study of rare disorders of pregnancy and childbirth of the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists