Georg Kolbe

Georg Kolbe (born April 15, 1877 in Waldheim , Saxony , † November 20, 1947 in Berlin ) was a figurative sculptor and medalist . The Georg Kolbe Prize and the Georg Kolbe Museum are named after him.

Career

Georg Kolbe was the fourth of six children of Theodor Emil and Caroline Ernestine Kolbe, nee Madder. His grandfather Gottfried Kolbe was a watchmaker and musician. Georg Kolbe's brother Rudolf , born in 1873, became a well-known architect and craftsman in Dresden .

Kolbe was trained to be a painter at the Dresden School of Applied Arts and the Munich Art Academy . In 1897 he went to Paris to study a semester at the Académie Julian . From 1898 to 1901 he lived in Rome , where he began with sculptural experiments under the guidance of Louis Tuaillon in 1900. In 1901 in Bayreuth , with the Wagner family, he met the Dutch singing student Benjamine van der Meer de Walcheren, whom he married on February 13, 1902 in Uccle near Brussels . The young couple moved to Leipzig , where their daughter Leonore was born on November 19, 1902.

1904-1932

In 1904 Kolbe moved to Berlin , where he lived until the end of his life. Kolbe became a member of the Berlin Secession in 1905 ; his most important art dealer was Paul Cassirer . In 1905 he was one of the first to receive the Villa Romana Prize , which was linked to a study visit to Florence . In 1909 he took part in the Salon d'Automne in Paris with several German artists and visited Auguste Rodin in Meudon . In 1910, he turned down the call to the Weimar School of Sculpture . In 1911 he was elected to the board of the Berlin Secession. After difficult beginnings, from 1910 Kolbe became more and more famous and successful. His most famous sculpture, The Dancer , was shown in the Berlin Secession in 1912 and then acquired by the Berlin National Gallery. A trip to Egypt in 1913 was significant for his style development .

After the outbreak of the First World War , Kolbe first worked as a volunteer soldier as a driver on the Eastern Front , then he trained as a pilot, but was not deployed. At the beginning of 1917 he was drafted and drafted into military service. In May 1917 he followed an appointment to Istanbul , where his friend Richard von Kühlmann was ambassador. Through his advocacy, he was spared active military service. His job was to erect a memorial to the fallen in the cemetery in the suburb of Tarabya . He also portrayed diplomats, the military and the young Turkish politician Talât Pascha . In 1918 he received the title of professor from the Prussian Ministry of Culture .

After his return to Berlin in early 1919, he was appointed a member of the Prussian Academy of the Arts . However, Kolbe was also a member of the revolutionary art work council and from 1919 to 1921 president of the Free Secession Berlin. His changed style, which appears to be influenced by Expressionism , was presented in a large exhibition in the Cassirer Gallery in 1921 and in the monograph by Wilhelm Reinhold Valentiner in 1922 .

Kolbe was more successful in the second half of the 1920s when he returned to more natural proportions of his figures. His works have been shown in numerous solo and group exhibitions. For the first time, some sculptures were sold in larger editions. The portrait commissions were numerous. Several works have been publicly established: the Marburger Crouching, the Creeping in the Hamburg city park , in the Cecilie gardens in Berlin-Schöneberg , the two figures , the morning and the evening , the morning was as gypsum in the Barcelona Pavilion by Mies van der Rohe at the World's Fair exhibited in Barcelona in 1929 , a genius in the opera house, Die Nacht in Rundfunkhaus Berlin and the Rathenau fountain in the Rehberge park . In 1927 Kolbe received an honorary doctorate from the University of Marburg .

On February 7, 1927, his wife, Benjamine, died. This was a stroke of fate for Kolbe at the time of his highest recognition, and mourning figures reflect his inner situation afterwards, especially the statue The Lonely in 1927 . For the artist, one way out seemed to be to deal with heroic monument projects; until his death he was working on a Beethoven - and Nietzsche -Denkmal. Kolbe retired from the lively Tiergarten art district to his newly built studio house in Berlin-Westend , near the cemetery where his wife was buried. In 1931 he took part in the exhibition at the Prague Secession .

1933-1947

In 1932 Kolbe traveled to Moscow . In January 1933 he published his very positive travel impressions in the left-liberal , anti-National Socialist weekly newspaper Das Tage-Buch . From private letters it emerges that he warned against the National Socialists years before 1933 and did not become a friend of the National Socialist idea later either. Initially, Kolbe did not see himself as an artist particularly valued by the new regime. He was considered a representative of the Weimar Republic and was attacked for various reasons, for example by Hugo Lederer in 1925 because of his portrait bust of Friedrich Ebert . (A cast of the bust made in 1987 is in the office of the Federal President in Bellevue Palace.) Lederer thought it was stylistically dubious and spoke out against its display in the Reichstag; Bernhard Bleeker recommended by Lederer then created a generally accepted Ebert bust. By 1935, a number of his publicly displayed works had been removed, such as the Heine monument in Frankfurt am Main, the Rathenau monument in Berlin, but also the statue in the Berlin opera house. However, the Heine memorial was preserved under the name “Spring Song” in the garden of the Städel Museum. The Heinedenkmal for Düsseldorf was no longer erected in 1933, but the bronze remained, hidden in the Museum Kunstpalast there.

In the following period, Kolbe received several public, mostly municipal commissions, for example the statue of a standing youth in Düsseldorf on Kaiserswerther Strasse in front of the Drahthaus . In 1934 Kolbe accepted the order for a war memorial for Stralsund after a design by Ernst Barlach had been rejected as "cultural Bolshevik". Barlach wanted to put the grief over the victims in the foreground, while Kolbe represents a couple of men; here a middle-aged man hands a sword propped up on the ground to a younger one. The inscription “You did not die in vain”, which is not from the artist, can, like the memorial, be seen as revanchist. The art historian Wilhelm Pinder interpreted in 1937: "The older one takes it [the sword] above the younger hand - he will one day leave it to her". The memorial met with divided approval: it had been criticized by the NSDAP district leader as "too sporty", while it was welcomed by NS art criticism. Dietrich Schubert wrote in 2004: "[...] Kolbe unequivocally placed his sword holders for Stralsund under the perspective of a renewed war with the Führer Hitler and the party [...]"

After the death of Reich President Paul von Hindenburg in August 1934, Kolbe - like Ernst Barlach , Erich Heckel and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe - signed the so-called " Call of the cultural workers " for a " referendum " on the unification of the Reich President and Chancellery in person Adolf Hitler . As the last president of the German Association of Artists , he was committed to helping colleagues classified as “ degenerate ” - but in vain: the renowned artists' association was banned in 1936, the current annual exhibition at the Hamburg Art Association was forcibly closed and its members transferred to the Reich Chamber of Culture .

From 1937 to 1944, Kolbe regularly took part with sculptures in the Great German Art Exhibition in the Haus der Kunst in Munich , which was touted as the most important National Socialist art event. The buyers of his sculptures included Adolf Hitler ( Young Woman , Sculpture, 1938), the Reich Minister of Culture Bernhard Rust ( The Guardian , Sculpture, 1938) and the Reich Minister of Economics, Walter Funk ( Descending , Sculpture 1940). The sculptor received honors such as the Goethe Prize of the city of Frankfurt in 1936, the Goethe plaque of the city of Frankfurt am Main in 1937 and the Goethe Medal for Art and Science, which goes back directly to Adolf Hitler, in 1942 . He was represented with two statues on the Reichssportfeld (today: Olympiagelände Berlin), and made some bronzes for barracks of the Wehrmacht . Obviously he did not comply with the request for a portrait of Hitler. However, in 1939 Kolbe created a portrait bust of the Spanish dictator Franco on behalf of the German-Spanish economic organization Hisma , which was presented to Adolf Hitler on his birthday that same year. He thanked Hisma "warmly for the bronze bust of Generalissimo Franco created by Georg Kolbe". This prompted John Heartfield to create his collage Brauner Künstlertraum . In 1944, in the final phase of the Second World War , Kolbe was included by Hitler on the special list of the Gottbegnadetenliste with the twelve most important visual artists of the Nazi regime.

Nonetheless, the National Socialists did not succeed in winning over Kolbe, who refused to make gigantic "giants" like the "state sculptors" Arno Breker and Josef Thorak (which did not prevent him from creating oversized large-scale sculptures). Kolbe had to accept the destruction and confiscation of some of his works (such as Die Nacht ), other works were rejected by ethnic circles as unheroic, humanistic or even “African” and “Eastern”, but Kolbe's niche was the bourgeois art market, which was based on taste of the early 1930s and its tradition: many artists and bourgeois art lovers distanced themselves from the dictatorship by withdrawing to their aesthetics . From their idealistic point of view, they saw the beauty in the athletic figures of Georg Kolbe and considered the statements about the racial purity of the portrayed to be vulgar . "The aesthetic and idealistic claim of many artists and art lovers turned out to be an escape from reality, not even being able to face the confrontation here ..." as an exhibition catalog from the Georg Kolbe Museum summarizes. Kolbe had, however, advocated an aesthetic, idealistic claim from the start; he had never been a critical realist.

Kolbe was diagnosed with bladder cancer in 1939 . The operation by Ferdinand Sauerbruch seemed to be successful. In 1943 the studio house was damaged in an air raid. Found in an emergency shelter in Silesia , Kolbe returned to Berlin in January 1945. Increasing blindness and the renewed outbreak of cancer made the last phase of life difficult. Georg Kolbe died in November 1947 at the age of 70 in St. Hedwig Hospital in Berlin.

It was not until after Kolbe's death that the Beethoven monument (in the ramparts ) and the ring of statues (in Rothschild Park) were erected in Frankfurt am Main . The realization of the Nietzsche monument in Weimar failed because of Hitler's objection.

Kolbe's works, which were in demand in bourgeois circles before 1933 and also enjoyed great recognition in National Socialist Germany, were exhibited again after the end of the war in 1946 at the First General German Art Exhibition in Dresden in the Soviet zone of occupation . In West and East Germany, the artist was considered a “true humanist-realistic tradition”. He was valued in all four systems of government, the Weimar Republic, the National Socialist system of injustice, in both socialist and capitalist post-war Germany.

tomb

Georg Kolbe's grave is in the Heerstrasse cemetery in Berlin-Westend (grave location: 2-D-4). He rests there next to his wife Benjamin, who committed suicide in 1927. Kolbe himself designed the artistically significant grave monument, consisting of three slim, high marble steles in an expressionist style and four grave slabs arranged in front of them, made by Josef Gobes. The middle stele shows the portrait of Benjamin Kolbe in three variants. The side steles bear the inscriptions "Terra" (earth) and "Coeli" (heaven) on the capitals. Kolbe apparently chose the unusual shape of rod-like grave monuments so that he could see the grave from the upper floor of the residential and studio house, which he built in 1928/1929 in the nearby Sensenburger Allee and which is now used as the Georg Kolbe Museum . The daughter Leonore (1902–1981) and her husband Kurt von Keudell (1896–1978) were later buried in the grave complex at the Heerstrasse cemetery.

The Kolbe grave complex, badly damaged by an explosive bomb in World War II and weathered in the decades that followed, was extensively restored by 2015 on the initiative of the former Berlin state curator Helmut Engel . Special attention was paid to the removal of the damage to the steles, the cleaning and lifting of the sagged grave slabs and the horticultural design and embedding of the facility.

By resolution of the Berlin Senate , the last resting place of Georg Kolbe in the Heerstraße cemetery has been dedicated as an honorary grave of the State of Berlin since 1990 . The dedication was extended in 2016 by the now usual period of twenty years.

Kolbe's studio house in Berlin

In 1928/1929 Kolbe built a studio house in cooperation with the Swiss architect Ernst Rentsch on Sensburger Allee in Berlin-Westend. Shortly afterwards, the neighboring house was built for Kolbe's daughter. What was striking about the studio house was the brick construction , the merging rooms flooded with daylight, the roof terrace and the sculpture courtyard and garden in the middle of pines and deciduous trees.

Kolbe lived in the house until his death in 1947. The damage caused by an air mine in 1943 could be repaired with the help of the Americans while he was still alive. In his will, Kolbe determined that his work should be made publicly accessible in his studio house. His estate included 200 sculptures, over 1,000 drawings, plaster models and his written estate. A foundation emerged from his estate in 1949 and opened the Georg Kolbe Museum in 1950 . This was able to maintain the original studio atmosphere of the house until the end of the 1960s.

From 1969 the studio was used as an exhibition house. Since 1978 the museum has received subsidies from the State of Berlin. One condition for this was that the house did not show just one artist. There were new acquisitions by artists from the first half of the 20th century. The exhibition activity, which is essentially limited to works of sculpture, was intensified. As a result, the number of visitors has increased roughly twentyfold.

In 1996, the group of architects AGP (Heidenreich, Meier, Polensky, Zeumer) created an extension with two basement floors (an exhibition room and a depot) and a direct connection to the studio building. The exhibition area was more than doubled.

About 200 meters from the Kolbehaus in Sensburger Allee, in the direction of the Olympiastadion , there is the “Georg-Kolbe-Hain” with posthumous casts of five large bronzes from the 1930s and 1940s.

Style phases

At the beginning of Georg Kolbe's work there are symbolist paintings and graphics. He was influenced by Max Klinger , who also supported him. Without training as a sculptor, he began to model heads around 1900. The first sculptures that were created afterwards show, comparable to the earlier and painterly works, pathetic compositions. After moving to Berlin in 1904, Kolbe gave up painting. In the second half of the 1910s, the motifs of his sculptures were simplified, he concentrated on individual figures, mostly nude figures of young women.

Kolbe developed his own style since 1910, which he expressed in the sculpture The Dancer . An expressionist phase followed, followed by an impressionist phase in the mid-1920s . After the death of his wife in 1927, he took back the emotion that had previously been characteristic of his work; now standing figures dominate. Characteristic for his entire work are naturally designed figures that evoke a dreamy mood when viewed.

Works (selection)

Georg Kolbe created almost 1,000 different sculptures, a considerable number of which have not survived. The number of drawings exceeds 2000 sheets.

Kolbe's works are represented in museums in Europe, the USA and Russia . Its market value in the art market is high; up to 1.2 million US dollars were paid for his sculptures .

- 1902: Portrait of a woman ( Dresden )

- around 1911: Portrait of Viola Tegtmeyer. Bust in bronze. Behnhaus , Lübeck

- 1912: The Dancer ( National Gallery , Berlin )

- 1912: The Bach Nymph ( Bonn - Bad Godesberg , Redoutenpark)

- 1913: Heine monument ( Taunus plant , Frankfurt am Main )

- 1913–1919: The Dancer , Hamburger Kunsthalle

- 1914–1917: Bellona , Wuppertal , Casino Garden

- 1917/1918: War memorial for the burial place in the embassy park of Therabia (today: Tarabya ) on the European side of Istanbul , Turkey . From a five-ton block of light shell limestone, Kolbe made an angel on whose knees a warrior breathes his life.

- 1921: Assunta

- 1924: The proclamation in the community gardens in Lübeck, the draft of the memorial for fallen booksellers of the First World War in Leipzig.

- 1925: The morning and the evening , Ceciliengärten , Berlin. The statue Der Morgen was in the German Pavilion in 1929 at the world exhibition in Barcelona

- 1926: War memorial 1914–1918 in Buchschlag near Frankfurt am Main

- 1926–1930: Big Night , Hamburger Kunsthalle. Bronze casting.

- 1926–1947: Beethoven monument in Frankfurt am Main

- 1927: Two sculptures bathing women (couple) made of shell limestone flank the entrance to the playground of the Hamburg city park and the beginning of the axis from Otto-Wels-Straße (formerly: Hindenburgstraße) to Stadtparksee.

- 1930: Rathenau fountain in the Rehberge park in Berlin

- 1931–1933: Heinrich Heine Memorial Rising Young Man in the Ehrenhof , Düsseldorf

- 1933, 1935: Decathlete and resting athlete on the Berlin Olympic site

- 1935: Young warrior , formerly at the Flensburg ZOB , today at the Mürwik Naval School

- 1936: Großer Wächter , larger than life bronze for a barracks in Lüdenscheid , now in the city center

- 1936/1937: Couple of people , at the Maschsee , Hanover

- 1939: Standing youth , since 1952 in front of the Drahthaus in Düsseldorf-Golzheim

- 1945: The Liberated

In addition, around 200 portraits, including Henry van de Velde (1913); Harry Graf Kessler (1916); Richard von Kühlmann (1917); Friedrich Ebert (1925); Edith von Schrenck (1929); Ferruccio Busoni (1925); Gret Palucca (1925); Max Slevogt (1926); Hans Prinzhorn (1933); Max Liebermann (1929), self-portrait (1925 and 1934).

- Works

Heinrich Heine Memorial , 1913,

in Frankfurt am MainBellona from 1922, casino garden in Wuppertal

The morning and the evening , 1925, in the Cecilien Gardens in Berlin

Bathing women (couple), 1927, Hamburger Stadtpark

Flying Genius , 1928, Ludwigshafen

Rathenaubrunnen , 1930, Volkspark Rehberge , Berlin-Wedding

Dionysus , 1931/36, replica from 1962

Berlin-WestendMarine Museum, 1935, Stralsund

Resting athlete , 1936, German Sports Forum

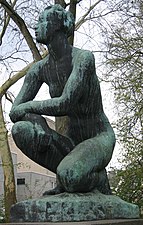

Crouching in the garden of the Marburg Art Museum

" Hands " of the Lübeck sisterhood of the German Red Cross in the Vorwerker cemetery

Collections

- Georg Kolbe Museum , Berlin-Westend . Around 200 sculptures and 1,500 drawings and graphics are kept in the artist's former studio and home.

- Small gallery in the Waldheim cultural center, Waldheim

Exhibitions

- 2014: Georg Kolbe and the First World War. Georg Kolbe Museum, Berlin.

- 2013: In the sculptor's studio. Visiting Georg Kolbe. Georg Kolbe Museum, Berlin.

literature

- Julia Wallner : Georg Kolbe. Wienand Verlag, Cologne 2017, ISBN 978-3-86832-333-7 .

- Wilhelm Pinder : Georg Kolbe. Works from the last few years. Reflections on Kolbe's sculpture. Rembrandt Verlag, Berlin 1937.

- Georg Kolbe: Images - Selected by the artist. (= Insel-Bücherei . 422/2). (Preface by Richard Scheibe). Insel Verlag, Leipzig 1939.

- Georg Kolbe Museum, Berlin (compilation): Georg Kolbe - 42 picture panels. With a preface by Richard Scheibe. Hans Schwarz Verlag, Bayreuth undated (around 1965).

- Georg-Kolbe-Museum, Berlin (ed.): Leaflet with life data and text on the development of Kolbe's style and the studio house. Berlin undated (around 1980).

- Ursel Berger : Georg Kolbe and the dance. (Exhibition catalog). Georg Kolbe Museum Berlin, Berlin 2003.

- Ursel Berger: Georg Kolbe - life and work. Gebr. Mann Verlag, Berlin 1990. (2nd edition. 1994)

- Robert Thoms: Great German Art Exhibition Munich 1937–1944. Directory of artists in two volumes, Volume II: Sculptors. Berlin 2011, ISBN 978-3-937294-02-5 .

- Rudolf G. Binding : From the life of plastic. Content and beauty of Georg Kolbe's work. H. Rauschenberg Verlag, Stollhamm-Berlin 1933. (8 editions)

- The Dictionary of Art. Vol. 18. MacMillan Publ. Lim., Grove 1996.

- Ursel Berger, Josephine Gabler (ed.): Georg Kolbe, residential and studio house - architecture and history. JOVIS Verlag, Berlin 2000, ISBN 3-931321-62-2 .

- Taking Positions: The Fall of a Tradition - Figurative Sculpture and the Third Reich. Henry Moore Institute, Leeds 2001, ISBN 1-900081-97-0 .

- Rolf Günther: The symbolism in Saxony 1870-1920. Sandstein, Dresden 2005, ISBN 3-937602-36-4 .

- Georg Kolbe . In: Hans Vollmer (Hrsg.): General lexicon of fine artists from antiquity to the present . Founded by Ulrich Thieme and Felix Becker . tape 21 : Knip – Kruger . EA Seemann, Leipzig 1927, p. 229-230 .

- Georg Kolbe . In: Hans Vollmer (Hrsg.): General Lexicon of Fine Artists of the XX. Century. tape 3 : K-P . EA Seemann, Leipzig 1956, p. 88 f .

- Maria Freifrau von Tiesenhausen: Kolbe, Georg. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 12, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1980, ISBN 3-428-00193-1 , p. 445 f. ( Digitized version ).

- Martin Ammermüller : The eventful life of the Godesberg nymph by Georg Kolbe. In: Association for Homeland Care and Local History Bad Godesbergs e. V. (Ed.): Godesberger Heimatblätter. Volume 52. Bonn 2014, ISSN 0436-1024 , pp. 7-80.

- Georg Kolbe - On the way of art. (Preface by Ivo Beucker) Konrad Lemmer Verlag, 1949.

- Literature by and about Georg Kolbe in the catalog of the German National Library

Web links

- Old and new views of his hometown Waldheim, as well as its history

- Works by and about Georg Kolbe in the German Digital Library

- Newspaper article about Georg Kolbe in the 20th century press kit of the ZBW - Leibniz Information Center for Economics .

- Search for Georg Kolbe in the SPK digital portal of the Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation

- Photo: Self-portrait Georg Kolbe, bronze, 1934

- Georg Kolbe biography of the Georg Kolbe Museum

- Biography and works of Georg Kolbe

- Company photos

- Figure numerous works by Kolbe in an English website (Engl.)

- Photos of the Georg Kolbe Adam monument in Frankfurt's main cemetery

- Photos of the Georg-Kolbe Beethoven Monument in the Taunusanlage in Frankfurt am Main

- Photos of the Georg Kolbe Heinrich Heine Monument in the Taunusanlage in Frankfurt am Main

- Photos of the Georg-Kolbe Monument Ring of Statues in Rothschild Park in Frankfurt am Main

- Photo: Statue Der Morgen by Georg Kolbe in the German Pavilion (1929) in Barcelona

- Works at the Great German Art Exhibition in Munich

Individual evidence

- ↑ In Georg Kolbe . In: Hans Vollmer (Hrsg.): General Lexicon of Fine Artists of the XX. Century. tape 3 : K-P . EA Seemann, Leipzig 1956, p. 88 f . Kolbe's date of birth and death are incorrectly stated. April 13 instead of April 15, 1877 and November 15 instead of November 20, 1947. Since this source is used frequently, these incorrect dates are also cited elsewhere. In the archive of the Georg Kolbe Museum , the data are documented several times and without any doubt. The data have been corrected in Vollmer Volume 6, p. 157.

- ^ Artist: Georg Kolbe. German Society for Medal Art V., accessed on November 24, 2015 .

- ↑ Ebert bust by Georg Kolbe. Retrieved May 5, 2017 .

- ↑ Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development: New Year's reception / picture gallery. Retrieved July 25, 2019 .

- ↑ commons.wikimedia.org

- ↑ Georg Kolbe: Design for the Stralsund Warrior Memorial 1934/35. Retrieved October 11, 2017 .

- ↑ Werner Stockfisch: Order against chaos. On Georg Kolbe's image of man.

- ↑ Detlev Brunner: Stralsund: A city in system change from the end of the empire to the 1960s. Publications on SBZ / GDR research in the Institute for Contemporary History. (= Sources and representations on contemporary history. Volume 80). Walter de Gruyter, Munich, 2010, ISBN 978-3-486-59805-6 , p. 98.

- ^ Dietrich Schubert, in: Martin Warnke u. a .: Political art: gestures and behavior. Akademie Verlag, 2004, ISBN 3-05-004060-2 , p. 86ff.

- ^ Ernst Klee : The culture lexicon for the Third Reich. Who was what before and after 1945. S. Fischer, Frankfurt am Main 2007, ISBN 978-3-10-039326-5 , p. 326.

- ↑ kuenstlerbund.de: Painting and Sculpture in Germany 1936 ( Memento of the original from March 4, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link has been inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (accessed on September 19, 2015)

- ↑ Harry Balkow-Gölitzer , Bettina Biedermann, Rüdiger Reitmeier, Burkhardt Sonnenstuhl, Jörg Riedel: Celebrities in Berlin-Westend - And their stories. Berlin Edition, 2007, ISBN 978-3-8148-0158-2 , p. 126.

- ↑ Beethovenhaus Bonn: Heartfield collage, photography, 39.8 × 28.5 cm. Text above right: “Brown artist's dream / 'The Berlin sculptor Georg Kolbe received / the honorable commission to create a memorial for / Generalissimo Franco. At the same time he was entrusted with the production of a / Beethoven memorial for the city of Frankfurt / am Main. ' / Berlin newspaper report "; in the picture below: “Talk to yourself in a dream: 'Franco and Beethoven, how do I do this? / The best thing to do is to make a centaur, half animal, half human. '"/ Mounted: John Heartfield

- ^ Ernst Klee: The culture lexicon for the Third Reich. Who was what before and after 1945. S. Fischer, Frankfurt am Main 2007, p. 326.

- ↑ Die Woche im Bild (Berlin): Illustrated supplement of the 'Berliner Zeitung', including the work of the sculptor Georg Kolbe. In: inventory no. Do2 2005/3325. German Historical Museum, accessed on October 30, 2019 .

- ↑ Josephine Gabler: Adaptation in dissent. In: Taking Positions (Fall of a Tradition - Figural Sculpture and the Third Reich). Henry Moore Institute, Leeds 2001, ISBN 1-900081-97-0 , p. 50.

- ↑ Arie Hartog: A clean tradition? In: Penelope Curtis, Ursel Berger (ed.): Taking Positions (Fall of a Tradition - Figural Sculpture and the Third Reich). Published for exhibition at the Henry Moore Institute, Leeds, 2001; Georg Kolbe Museum, Berlin; 2002; Gerhard-Marcks-Haus, Bremen, 2002. Henry Moore Institute, Leeds 2001, ISBN 1-900081-97-0 , p. 39.

- ↑ Ursel Berger : "Sensation is everything". The figure sculptor Georg Kolbe. In: Georg Kolbe 1977–1947. Georg-Kolbe-Museum, Munich 1997, ISBN 3-7913-1909-4 , pp. 23–32.

- ^ Georg Holmsten : The Berlin Chronicle: Dates, People, Documents. Droste, 1984, ISBN 3-7700-0663-1 .

- ↑ Jürgen Krause: "Märtyrer" and "Prophet" - studies on the Nietzsche cult in the visual arts of the turn of the century. Walter de Gruyter, 1984, ISBN 3-11-009818-0 , p. 231.

- ↑ Wolfgang Benz, Hermann Graml, Hermann Weiss (Eds.): Enzyklopädie des Nationalozialismus, Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart, 1997, ISBN 978-3-60891805-2 , p. 158

- ↑ Kathleen Schröter: Art between the systems. The General German Art Exhibition in Dresden in 1946 . In: Nikola Doll (Ed.): Art history after 1945: Continuity and a new beginning in Germany , Böhlau, Köln-Weimar, 2006, ISBN 978-3-41200406-4 , p. 224

- ^ Hans-Jürgen Mende : Lexicon of Berlin burial places . Pharus-Plan, Berlin 2018, ISBN 978-3-86514-206-1 . P. 485.

- ↑ Kolbe burial site . In: Jörg Haspel, Klaus von Krosigk (Ed.): Garden monuments in Berlin . Graveyards. Imhof, Petersberg 2008, ISBN 978-3-86568-293-2 . P. 36. Kessler: Diary 1923–1926 . P. 710.

- ^ Charlene Rautenberg: Restoration of Georg Kolbe's tomb completed . In: Berliner Morgenpost . September 22, 2015. Accessed November 13, 2019.

- ↑ Senate Department for the Environment, Transport and Climate Protection: Honorary Graves of the State of Berlin (Status: November 2018) (PDF, 413 kB), p. 45. Accessed on November 13, 2019. Recognition and further conservation of graves as honorary graves of the State of Berlin (PDF , 205 kB). Berlin House of Representatives, printed matter 17/3105 of July 13, 2016, p. 1 and Annex 2, p. 8. Accessed on November 13, 2019.

- ↑ Information on the back of an entrance ticket from around 1980.

- ^ Page from Christie's, accessed September 22, 2017.

- ↑ Horst-Pierre Bothien, Erhard Stang: Mysterious Bonn. Gudensberg equals. Wartberg Verlag, 2003, ISBN 3-8313-1342-3 , p. 45.

- ^ Announcement on the exhibition ( Memento of November 29, 2014 in the Internet Archive ), accessed on November 19, 2014.

- ^ Announcement on the exhibition ( Memento of November 12, 2014 in the Internet Archive ), accessed on November 19, 2014.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Kolbe, Georg |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | German sculptor |

| DATE OF BIRTH | April 15, 1877 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Waldheim , Saxony |

| DATE OF DEATH | November 20, 1947 |

| Place of death | Berlin |