Hugo Lederer

Hugo Lederer (born November 16, 1871 in Znojmo , Austria-Hungary , † August 1, 1940 in Berlin ) was a German sculptor and medalist . He lived and worked in Berlin during the reign of Kaiser Wilhelm II and the first German democracy; his art was decorative and apolitical.

Training and first successes

Between 1884 and 1888 Lederer attended the kuk technical college for the clay industry in Znojmo . Immediately after graduating, Adalbert Deutschmann hired him for his arts and crafts studio in Erfurt . Lederer did not receive any academic training.

In 1890 Lederer moved to Dresden in the workshop of the sculptor Johannes Schilling . Two years later, the sculptor Christian Behrens recruited him to Breslau . But that same year, Lederer went to Berlin to see Robert Toberentz .

In 1895 he started his own business as a freelance sculptor and settled in Berlin. For a while - until 1924 - he lived and worked in the Atelierhaus Siegmundshof 11 in Berlin-Tiergarten, where August Gaul and, since 1912, Käthe Kollwitz had their sculptor studios. He then moved to Knesebeckstrasse 45 and received studio space at Hardenbergstrasse 34 in the College of Fine Arts. His first public commission, a genius group for Krefeld , he received in 1898. This was followed by the Bismarck monument in Wuppertal-Barmen. In 1901 his design , 'The courage of youth, wisdom of age' ( fencing fountain) won the second prize (600 M) in the competition for a decorative fountain on the University Square in Breslau - it was intended for execution and inaugurated in 1904. He achieved his greatest success in 1902 in the competition for a colossal Bismarck monument in Hamburg , when one of his two submitted designs, which Roland-Bismarck conceived together with the architect Johann Emil Schaudt , was awarded a prize and was determined to be executed - the monument inauguration took place in 1906 . In 1903, a jury at the Great Berlin Art Exhibition awarded him the Small Gold Medal . Together with Hermann Feuerhahn and other sculptors, he founded the workshops for cemetery art in 1905 . In 1907 he was commissioned to create the larger than life equestrian statue of “St. George after the victory over the dragon” for the newly built “State Museum for the Province of Westphalia” in Münster, which has graced the east facade of the building since 1908. It was only when he was appointed professor in 1909 that the cooperative of the full members of the Royal Academy of Arts chose him as the “local full member” of the Academy of Arts (previous applications for admission had been rejected).

In 1910 he came fourth in the competition for a monumental fountain for Buenos Aires. His design, which he had designed with reference to beef production in Argentina, he sold to the city of Berlin in 1927 as the “bull fountain / fertility fountain” (installation in 1934 on Arnswalder Platz ). Accompanied by the benevolence of art critics, he began to work on the Heine monument for Hamburg in 1911; the 2.25 m high bronze statue was cast on July 8, 1913 (it was installed in the Hamburg city park in 1926). At the same time he made the equestrian monument for Emperor Friedrich III. in Aachen , it was unveiled in 1911 in the presence of His Majesty Kaiser Wilhelm II. The latter then ensured that Lederer was entrusted with the management of the sculpture class at the University of Fine Arts , as the successor to Prof. Ernst Herter .

First World War and Weimar Republic

Lederer had been a member of the German Society 1914 political club since 1915 . He was used as an expert by the state advice center for war honors formed in 1916. In 1915 General Field Marshal Paul von Hindenburg appointed him and other artists to the Army High Command on the Eastern Front ( Upper East ) in Kovno, in order to have them portray them effectively in the media. Their achievements probably fell short of expectations, because in November 1915, Academy President Ludwig Manzel was called in , and Hindenburg's portrait bust and statuette were only given unreserved approval. In 1919 the Academy of Arts in Berlin appointed Lederer to its Senate and, as the successor to Louis Tuaillon, headed one of the state's master workshops for sculpture. Lederer received the large master's studio on the east side of the University of Fine Arts. On April 13, 1921 he became civil servant. He belonged to the "Decoration Commission" of the Reichstag, consisting of the President of the Reichstag, the Reichstag director and a large number of MPs, together with Ludwig Hoffmann and Arthur Kampf as a non-voting advisory board. On June 7, 1923 he was accepted into the order Pour le Mérite for science and the arts together with Albert Einstein , Max Liebermann and Felix Klein . In 1925 the Academy of Fine Arts in Munich made him an honorary member. He was also a member of the German Society of Sciences and Arts for the Czechoslovak Republic and between 1922 and 1932 created several works for clients there, e. B. for the metallurgical company in Brno, the shift works in Ústí nad Labem (Aussig). He created a Goethe monument for Teplice - the ceremonial unveiling took place in Lederer's presence on May 9, 1932. His works were exhibited in Brno and Znojmo as early as 1910 and 1914, again in Brno in 1928, and in the Prague National Gallery in 1936.

When the German Sports Forum was built in Berlin from 1926 to 1928 , several of his sports-related sculptures ( wrestler / winner from 1908, archer from 1916/21, Diana from 1916, winner from 1927, runner group from 1928) are public in the urban area of Berlin and the Cupid Fountain from 1928 on the grounds of the Sportforum itself. Among local politicians in Berlin, it had potent patrons a. a. Mayor Gustav Böß and city architect Ludwig Hoffmann , he that additional post-Wilhelmine sculptures and plants for decoration of public space to the city to sell could: the Bärenbrunnen on Werderscher market, the nursing mother bear outside the town hall Zehlendorf and fertility fountain on the Arnswalder space these works still exist today. But large industrialists from all sectors also ordered works from Lederer, such as B. the "steel baron" Friedrich Krupp (monuments, building decorations, portrait busts) and the art-loving poison gas promoter Friedrich Carl Duisberg (portrait bust, Caritas fountain). Lederer portrayed Gustav Stresemann and in 1929 was commissioned to cast the death mask and design the grave of the deceased Nobel Peace Prize laureate. For the project initiated by Chancellor Marx and Reich President Ebert in 1924 for a national memorial for the fallen soldiers of the World War ( Reichsehrenmal ), Lederer created a model without being asked , which was published in 1929 by representatives of the front-line soldiers' associations ( steel helmet , Reichsbundischer Frontsoldaten , Reichsbanner Schwarz-Rot-Gold ) was inspected and approved in the studio. When a competition was still advertised in 1931 and his design was unsuccessful, he responded with personal failures, which were made public by the press on July 13, 1932 and were ultimately blamed for his psychiatric illness (including by Reichskunstwart Edwin Redslob ). From 1929–1931 he was involved in the “Committee for the Preservation of Kurt Kroner's Life Achievement ”, together with Kroner's widow Ella (1885–1942), Gerhart Hauptmann , Max Reinhardt , Leopold Jessner , Käthe Kollwitz , Georg Kolbe , Paul Löbe , Arthur Holitscher , Otto Warburg , Werner Sombart , Wilhelm Bölsche and numerous other celebrities. At the representative exhibition “German contemporary fine art and architecture”, which was shown in Beograd and Zagreb in 1931, he was represented with his Stresemann bust (alongside all the celebrities of the modern German art and architecture scene). On July 28, 1932 he polemicized in the Berliner Lokal-Anzeiger against the President of the Academy of Arts, Max Liebermann, because of his unusually long term of office; Liebermann resisted in the Official Prussian Press Service on July 29, 1932. At that time, Lederer had advocates such as Max Osborn, Fritz Stahl and Max Dessoir. Others like Reichskunstwart Edwin Redslob , the critics Karl Scheffler and Alfred Lichtwark , the central organ of the KPD “Rote Fahne”, the artist colleagues Max Liebermann , Ernst Barlach , Georg Kolbe and Heinrich Zille didn't like him very much.

The time of National Socialism

While Lederer had been honored with the order Pour le mérite (1923) and the Maximilian Order (1929) in the media in the twenties , he was hardly noticed after 1933. In the academy's spring exhibition in 1934, five of his works were exhibited, the portrait busts of Prof. Planck and Prof. Sering, the models 'relay runners changing baton', 'soccer group' and '200 m high speed runners in the final sprint' ; see. In 1936 only two early works, the Strauss bust and the fencer from 1902, were officially exhibited by the academy, after which none. Lederer was neither one of the “degenerate” artists, nor one of the representatives of the “true German art” exhibited at the “Great German Art Exhibitions” in Munich from 1937 to 1944. The Nazi controversy about the definition of “ German art ” from 1933–36 took no notice of Lederer, cf. His portrait style was deemed hollow and puffy and out of date for the Nazi regime. While before the First World War and in the Weimar Republic, his works were also and especially valued and bought by the Jewish upper class. a. von Eugen Gutmann , Heinrich Braun and Rudolf Mosse , Lederer did not earn any significant income from artistic activity during the Nazi era. For a long time he owed his compulsory contributions to the Reich Chamber of Culture and in 1937 applied for exemption from contributions due to lack of funds - the application was granted. In contrast to numerous other artists (Albiker, Wackerle, Mages, Meller, Raemisch, Kolbe, Breker , Strübe, Thorak and Wamper), he was not required for the visual design of the Olympic site in 1936. He also no longer received other public commissions (for example, for furnishing the Nazi party rally grounds in Nuremberg, which Speer and Hitler assigned to sculptors Josef Thorak, Kurt Schmid-Ehmen , Constantin Starck and Ernst Andreas Rauch from 1934–1940 ). The Krupp family commissioned him in 1936 with a memorial; this work was his last.

Since the beginning of 1933, Lederer repeatedly stayed away from the meetings of the Senate of the Academy of Arts due to illness.

On April 7, 1933, the Hitler government enacted its “ Law for the Restoration of the Professional Civil Service ”. Those who did not want to lose their civil servant status had to document their loyalty to the “government of the national survey” or to the “national state” according to §§ 2 and 4 and to prove their “Aryan descent” according to § 3. Thereupon millions of civil servants joined the NSDAP or its organizations, according to §§ 2 and 4. The Prussian civil servant Lederer, a native Austrian with German nationality, did so on May 1, 1933 (NSDAP membership number 2,673,576), but a few were against his academy colleagues did not join in 1935 either ( Alexander Amersdorffer , Schumann , Rulf, Körber, Streiter, Hedderich, Danneberg, Kiszio, Poelzig , Meid ). Lederer refused, like 27 other academy members, to comply with § 3, whereupon the then President of the Academy of Arts, Max von Schillings , called on the "expert (s) for race research at the Reich Ministry of the Interior" to investigate - unsuccessful with regard to Lederer, because his NS-compliant proof of parentage was not available in 1939 either. His son Heinz, on the other hand, had himself assessed as "Aryan" by the expert for race research in August 1933.

At the end of August 1933, the bronze statue of his Hamburg Heine monument was cleared away by the Nazi Senate (and melted down around 1943 for metal extraction). The 1.40 meter high stone base with decorative reliefs and the inscription HEINRICH-HEINE was only removed after 1936. Lederer's reactions to the destruction of his work of art are not documented. Alfred Kerr , the initiator of the monument and speaker at the unveiling ceremony, commented in 1938: “The monument was [...] erected by Hugo Lederer in Hamburg; Mayor Petersen and I unveiled it in 1926. (Today it is scrap. In the broken bronze there is probably a rhinoceros hoof.) "

Lederer did not sign the “Appeal of the Cultural Creators” in 1934 in favor of Adolf Hitler.

In 1934, Lederer approached Reich President Hindenburg directly with an initiative for a warrior memorial. The one and a half page long, clearly paranoid text, written “at a sunny dawn, 5 am on July 5, 1934”, refers to the incurable disease (progressive paralysis, ie, softening of the brain) from which Lederer suffered from around 1924 and eventually died in 1940 . For the chestnut-planted square behind the Neue Wache unter den Linden in Berlin, he decided: “Now, in the small chestnut grove, order should be taken, in the sense of Schinkel. My division, created by setting up 8 vases and in the middle a sixteen-sided plate with a column on which swords, shield and helmet. Everything embossed in copper, the helmet gold-plated. Close to the column are two jets of water reaching up, a deer and a doe grazing. These are supposed to symbolize the Brandenburg landscape. The names of the great military leaders - from the great Elector to Hindenburg - are to be affixed and gilded. The foundation stone is to be laid on Sedan - Moltke's big day. Let it be a prayer! ”Carefully written on a typewriter and signed in ink, he gave the Akademie der Künste a copy of all this; Academy secretary Professor Alexander Amersdorffer initialed the letter - no further reactions are known.

Contrary to the presentation by Sven-Wieland Stape (General Artist Lexicon LXXXIII, de Gruyter Berlin 2014) Hugo Lederer was not a member of the clean-up and confiscation commission “ degenerate art ”, which according to the ministerial decree of June 30, 1937 “the in the German Reich, Länder- and municipal owned works of decaying German art since 1910 [...] for the purpose of an exhibition and to secure ”. When Lederer retired on April 1, 1937 because he had reached the age limit, he asked to be allowed to continue to use his studio rooms at the university, which he was initially allowed to do. On July 15, 1937, he and a few other regular academy members were downgraded to the "inactive membership" category, newly defined by the Nazi regime, so that "there would be continual room for a younger generation to grow"; H. for the Nazi regime more approving people like u. a. Professor Arno Breker , Professor Josef Thorak , Gerhard Marcks , Wilhelm Furtwängler , Fritz Schumacher , Albert Speer (VC 2022 (a), quoted from Brenner). In 1938 Lederer's academic position of professor and head of a master's atelier for sculpture was filled with Arnold Waldschmidt , a staunch Hitler fascist, NSDAP and SS member. On July 9, 1938, Lederer claimed in a letter to Amersdorffer, “that the Führer and Reich Chancellor had acquired my bronze work 'Anna Pawlowa feeding a deer'. Place of installation: Garden of the Reich Chancellery in Berlin Wilhelmstrasse. ”The claim - unconfirmed and probably untrue - was made by Amersdorffer in his unpublished funeral speech on August 5, 1940 as an affair of the heart of the paranoid deceased. Neither the NS reporting on the funeral service nor the obituaries in NS art magazines dealt with this part of Amersdorffer's address.

Death and inheritance

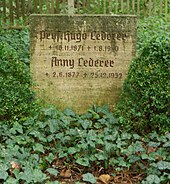

His illness overshadowed the last years of his life and prevented him from working as an artist. The correspondence with the Reich Ministry of Science, the Reich Chancellery and the Academy of Arts and the like. a. In 1939 his wife Anny and son Heinz occasionally led him because of the studio rooms he kept occupying. At the age of 68, he died on August 1, 1940 of progressive paralysis in the St. Franziskus Hospital in Berlin. On August 5th, a simple funeral service took place in the hospital chapel; Pastor Schubert and Professor Amersdorffer spoke. Propaganda Minister Goebbels had sent a wreath. Hugo Lederer found his final resting place in the Wilmersdorfer Waldfriedhof Stahnsdorf , as did his widow Anny in 1952. Son Heinz brought his artistic estate, which he had bequeathed to the museum in his hometown, to Znojmo in 1941. His entire personal estate in the possession of his widow burned in Berlin on March 1, 1943 due to the war. Some of his 300 or so well-known works can be found in museum magazines, e. B. in Berlin in the National Gallery, in the Berlinische Galerie-Museum für Moderne Kunst, in the Georg-Kolbe-Museum, but also in the Kunstforum Ostdeutsche Galerie in Regensburg, in the State Art Collections in Dresden and in the South Moravian Museum in Znojmo (Czech Republic). In public you can see Lederer's sculptures and installations in Aachen, Hamburg, Krefeld, Wrocław, Poznań, Frankfurt am Main, Berlin, Oldenburg, Eisenach, Münster and at cemeteries in Berlin, Kleve, Hamburg, Bielefeld, Cologne and Mainz . Some works are to be found in the stock of photo databases, e.g. B. at picture agency bpk, picture index of art and architecture Marburg, Getty-images, ullsteinbild, akg-images.

Lederer himself did not catalog his works. Hans Krey made his first efforts in the early 1930s for a complete catalog raisonné. Another list of Lederer works can be found in the estate of daughter Hilde Lederer in the Georg Kolbe Museum. The artist's youngest brother, the businessman Karl Lederer (1882–1971), continued these efforts after 1945. He handed over his collection of documents on the life and work of Hugo Lederer on May 23, 1965 to the former NSDAP activist Felix Bornemann (1894–1990) from the South Moravian Landscape Council in Geislingen, who soon felt the need to consider the artist a favorite of Hitler and inveterate To represent ethnic Germans. In Znojmo, Libor Šturc saw the remains of Lederer's artistic estate in 1996. The artist's great-nephew, Gerold Preiß (www.hugo-lederer.de) has been working on a comprehensive register since 2000. Lederer archives are located in the Hamburg State Archives, the Federal Archives Berlin, the Historical Archives of the Prussian Academy of the Arts Berlin, the Georg Kolbe Museum Berlin, the Berlin Gallery Berlin Archives, the National Gallery Berlin Archives, the Dresden Academy of Fine Arts archives, Archives of the South Moravian Museum Znojmo, archive of the South Moravian Landscape Council Geislingen / Steige.

Art historical classification

Lederer always stood on the side of upper-class modernism and against the anti-bourgeois left-wing or ethnic art scene. At first he still followed Reinhold Begas and its neo-baroque style, preferred by Kaiser Wilhelm II. And by many intellectuals at that time despised art movement of the early days . With his totemistic Roland-Bismarck, Lederer turned to the u. a. von Aby Warburg (1866–1929) welcomed the neoclassical style of Adolf von Hildebrand (Warburg: "loose from the theatrical baroque style and moment photography"). Warburg stated that the "[...] large audience [...] access to the man in the work of art is not granted through collegial equation or amiable approach, but only through a distance-keeping, objective deepening [...]", so the monument is "a comfortable approach between object and viewer ”did not allow - which also applied to Lederer's much smaller later still pictures u. a. the Heine monument. Lederer's ability to “summarize, large forms of expression” was also emphasized by the critic Max Osborn , who, by the way, predicted the Hohenzollern's taste in art: “The Roland-Bismarck at the Elbhafen will perhaps be the only work of the monumental last imperial era before the future.” According to the death of Louis Tuaillon on February 21, 1919 Hugo Lederer took over his master's studio in college. He was presented to the public as an equal successor: “Tuaillon and Lederer, after all, those were the two sculptors who had to represent the more tasteful Germany for the great need for monuments in the prewar period. The Bremen 'Kaiser Friedrich' (Tuaillon) and the Hamburg 'Bismarck' (Lederer) were monuments with which one could stand against everything that had arisen between Siegesallee and the Leipzig Battle of the Nations. Both: Tuaillon and Lederer were free of the pomposity, the false and exaggerated pathetics, were disciplined in their design and at the same time they had that dose of academics without which official monument commissions in Germany - and ... in the whole world would not be possible. "Significantly Both Kaiser Wilhelm II. in 1906 and Adolf Hitler in 1939 avoided Roland-Bismarck (whom they should have looked up to) during their visits to Hamburg.

Lederer stood in stark contrast to Impressionism, because he was enthusiastic about the beauty of ancient sculptures: “I have a very strong relationship with antiquity. The older I get, the stronger this relationship becomes. I go to the archaeological museum in the university almost every Sunday and often during the week to look at these wonderful plasters; it's like a church service for me. ”In 1925 he criticized a bust of the late Reich President Friedrich Ebert, modeled by Georg Kolbe impressionistically, as“ downright insulting [...] for the purpose to which it is supposed to be dedicated, for the whole people ”and was put down for this by the impressionism-friendly art critic ("pathological excitement"). In fact, Lederer was in psychiatric treatment at the time. For the design of his figures he used the “ancient treasure trove”, for example in 1920 in the competition for the monument to the fallen at the University of Berlin under the motto of Reinhold Seeberg “invictis victi victuri” (ie the undefeated the defeated winners of the future ). Lederer won the competition with the figure of an inferior, fateful, physically intact, antique-naked warrior, corresponding to the image motif “Death of Orpheus” or “Kneeling Persian”, cf. While his humbly bowed head was still covered with a World War II steel helmet in the plaster draft, he preferred an archaically stylized wreath of hair for the definitive granite figure from 1926. Among other things, because of its formal connection to antiquity, Lederer differed from Nazi art, which - according to Breker in 1936 - cultivated the trivial imitation of nature, both in the gigantic and in the trinkets .

Lederer did not deal with the competing styles of Cubism, Constructivism, Expressionism, Dadaism, New Objectivity, and Futurism, not even with Nazi art. Since it was of no importance for the history of the development of modern art, it is not mentioned in overviews of current art historiography. Although he did not establish his own tradition of sculpting himself, he did produce many artistically productive students and others. a. Karl Müller , Kurt Lauber, Paul Gruson, Fritz Melis , Wilhelm Heiner , Josef Thorak , Gustav Seitz , Emy Roeder , Hans Mettel , Ulrich Kottenrodt , Kurt Harald Isenstein , Otto Weissmüller, Frieda Riess , Theo Akkermann , August Tölken and in certain respects too Waldemar Grzimek and Katharina Heise .

Private

He was married to Anny, b. Lauffs (1877-1952); the couple had three children: Heinz (* 1905), Hilde (1907–1984) and Helmut (* 1912).

Awards and honors

Hugo Lederer received numerous medals and awards a. a. the order Pour le mérite for science and art (Prussia, 1923), the Maximilians order for art and science (Bavaria, 1929), the Nordstern order (Sweden, 1914), the title of Dr. hc from the University of Wroclaw (1908). In 2011 the directorate of the South Moravian Museum in Znojmo (formerly Znojmo) had a bronze plaque attached to his parents' house in memory of the important artist.

Posthumous appreciation

His works 'Fechter', 'Ringer', 'Peyrouse', 'Kauernde' and 'Strauss-Büste' were shown posthumously in the autumn exhibition of the Prussian Academy of the Arts in 1940. The Nazi press spread obituaries, which among other things blocked out his enormous success with the audience of the Weimar Republic (called "Systemzeit" in Nazi jargon) and only referred to the Wilhelmine "Second Reich" of the Wilhelminian era. Accordingly, Lederer apparently did not do justice to the "new", the Nazi zeitgeist.

Around 1965, the former NSDAP functionary Felix Bornemann (1894–1990) emerged as a Lederer expert for the first time. In his new field of activity in the Landsmannschaft der Sudeten Germans he organized exhibitions on Lederer's 25th anniversary of death and 100th birthday in 1965 and 1971 in the South Moravian Museum of Local History in Geislingen / Steige. Bornemann, who claimed to have known the artist personally, spread about Lederer's biography in the newspaper “Geislinger Fifthälerbote” in 1965 and in a brochure in 1971, without any appreciable response from art historians. The reception of Lederer after 1980 was largely determined by the art history dissertation by Ms. Jochum-Bohrmann, which was completed in 1988. a. Unchecked statements made by Bornemann that brought Lederer into connection with the NS. You and your supervisor Professor Dr. Dietrich Schubert brought Lederer not only personally, but also stylistically and ideologically close to the NS. His works are models for Nazi art, helped prepare the NS, and are jointly responsible for the NS. Schubert judged: “In the figures and warrior monuments that L. created since then [1919], nationalist attitudes and heroic tendencies in his art intensified. In these works, the National Socialist cultural theorists recognized 'forerunners of their own will' (R.Scholz 1940) ”. And: “In the sculpture of the 20s [...] it represents that teutomanic, monumentalizing style that implemented German national affects and thus formally and ideologically prepared the fascist sculpture. Lederer's late work belongs to Nazi art: in 1940, 'Art in the German Reich' celebrated those who died in Berlin as 'the forerunner of one's own will'. ”In a book contribution in 1990, Jochum-Bohrmann judged somewhat more differentiated.

In an obituary in the NS monthly “Die Kunst im Deutschen Reich” in 1940, the Nazi art functionary Robert Scholz suggested to his art-loving readership, who were familiar with Lederer, that Nazi sculpture would in future be based on Lederer. Apparently he was subject to a misjudgment (which was adopted by Schubert and Jochum-Bohrmann), because neither Breker, nor Kolbe, Thorak, Klimsch, Wandschneider, Wynand and other Nazi sculptors ever referred to their supposed role model Hugo Lederer.

Works (selection)

- 1893: "The Homecoming 1812", erected in 1925 as a war memorial in Kleve

- 1897: Genius figure group in Krefeld , on the extension of the Kaiser Wilhelm Museum

- 1900: Bismarck monument in Barmen

- 1901: Reliefs boys and girls in Berlin-Moabit , community dual school Wiclefstrasse

- 1901: Sculpture group "Der Abschied" at the family grave site "Cohen", Ohlsdorf cemetery

- 1901–1904: Fechterbrunnen in Breslau , Universitätsplatz

- 1903: Hallier tomb , Ohlsdorf cemetery

- 1905: Destiny (now in the Ohlsdorf cemetery in Hamburg)

- 1902–1906: Bismarck monument in Hamburg, Elbhöhe (with architect Johann Emil Schaudt )

- 1905: St. Georg in Münster , on the exterior of the Westphalian Provincial Museum

- 1908: Wrestler in Berlin-Westend on Heerstraße was also named winner in 1912 (Hellwag 1912)

- 1908: Bismarck bust in the Bismarck-Warte in Brandenburg an der Havel on the Marienberg (lost)

- 1909: Kronthal fountain in Posen / Poznań

- 1910: Competition draft for a Bismarck national monument on the Elisenhöhe near Bingerbrück (not awarded a prize)

- 1911: Fischpüddelchen fountain in Aachen

- 1911: Kaiser-Friedrich monument in Aachen , Kaiserplatz . One of the stone lions has been at the entrance to the Ferberpark in Burtscheid since 1960 .

- 1911–1926: Monument to Heinrich Heine in Hamburg, erected in the Stadtpark in 1926 (dismantled in 1933, melted down in 1943; a new creation by Waldemar Otto has been erected on the Rathausmarkt since 1982. She cites her model.)

- 1911–1927: Diana and Archer for the Lietzensee Park in Berlin (melted down in 1943). Diana was placed on Pariser Platz for 4 weeks in 1926, and then in Lietzensee-Park.

- 1912–1913: War memorial in Emmerich in the Rheinpark (together with Theodor Haake and Wilhelm Kreis )

- 1913: Memorial relief for Baron Carl von und zum Stein at the Schöneberg Town Hall , Freiherr-vom-Stein-Straße

- 1914: Tomb (sandstone stele) for Julius Rodenberg in Berlin, in the Friedrichsfelde central cemetery (the grave was extinguished in 1973)

- 1914: Still images of Fichte and Savignys for the auditorium of the Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität in the building of the Old Library in Berlin, in a magazine around 1960

- 1916 Merkur fountain in Frankfurt / Main

- 1920–1926 Memorial to the fallen at Berlin University, destroyed in World War II

- 1921–1924 Façade decorations on the newly built building of the Reich Debt Administration , Berlin Oranienstrasse / Alte Jakobstrasse

- 1921: Lion monument as a regimental war memorial of the Oldenburg Infantry Regiment No. 91 in Oldenburg , on Schlossplatz (moved to Theodor-Tantzen-Platz in 1960 )

- around 1925: War memorial in Altdamm , on the market square

- 1926 Medical monument in Eisenach for the German doctors who died in World War I (resembles the Hindenburg monument in Wuppertal-Barmen by Paul Wynand 1917)

- approx. 1926–1928: mourner , in the memorial hall at the main cemetery in Mainz

- 1927: Winner , set up in front of the sports field in Berlin-Köpenick (the pose corresponds to depictions of Roman general or Christian Daniel Rauch's depiction of Blücher ).

- 1927: Bust of Friedrich Kraus in Berlin-Mitte

- 1910–1934: Fertility fountain (bull fountain) in Prenzlauer Berg , Arnswalder Platz

- ca.1928: Anna Pavlovna, feeding a deer

- 1928: Bear fountain in Berlin-Mitte, Werderscher Markt

- 1928: Group of runners on Scholzplatz in Berlin-Westend , melted down in 1943

- 1928: Cenotaph to commemorate the dead Krupp workers on Holy Saturday 1923 at the south-west cemetery in Essen ; no longer received

- ca.1928 : Cupid's fountain in front of the Annaheim of the German Sports Forum (lost)

- 1929: Suckling bear in Berlin-Zehlendorf , town hall / tax office

- 1929–1930: Tomb for Gustav Stresemann in Berlin-Kreuzberg , on the Luisenstadt cemetery

- 1930: bust of Peter Cornelius , Mainz-Oberstadt

- 1930: Monument to Ernst Bassermann in Mannheim , at the entrance to the upper Luisenpark (not preserved)

- 1930: Facade decoration on an administration building of the shift works in Aussig

- 1936: Allegory of work , Villa Hügel in Essen , previous location in the hall of honor of the tower house of the Krupp headquarters

View of other works

Clio at the feet of Otto von Bismarck, Geschwister-Scholl-Platz (Wuppertal) -Barmen, 1900

Fencing fountain in Breslau , 1901–1904

Destiny , Ohlsdorf Cemetery , 1905

Detail from the Bismarck memorial in Hamburg, 1902–1906

Fischpüddelchen , Aachen, 1911

Bull fountain, Arnswalder Platz , Berlin, 1910–1934

Berlin, Schöneberg Town Hall , memorial relief for Karl Freiherr vom Stein , 1913

Memorial for the Krupp workers killed on Holy Saturday 1923 in the south-west cemetery in Essen ; not received

Medical memorial in Eisenach for the German doctors who died in World War I (picture from 2010), 1926

Bust of Friedrich Kraus in Berlin-Mitte, 1927

Bears , Martin-Buber-Strasse 20, Berlin-Zehlendorf , 1928

Former Cupid Fountain in front of the Annaheim of the German Sport Forum Berlin, around 1928

Group of runners on Scholzplatz in Berlin-Westend (district Pichelsberg ), 1928

" Runner ", 1929

Berlin-WestendBust of Gustav Stresemann

Monumental grave for Gustav Stresemann in the Luisenstadt cemetery in Berlin, 1930

Permanent exhibition

An exhibition of some of his designs can be found in the South Moravian Gallery in the Retz City Museum (Lower Austria).

literature

- Hugo Lederer. In: Austrian Biographical Lexicon 1815–1950 (ÖBL). Volume 5, Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, Vienna 1972, p. 83.

- Ilonka Jochum-Bohrmann: Hugo Lederer, a German national sculptor of the 20th century. Lang, Frankfurt am Main 1990, ISBN 3-631-42632-1 .

- Ilonka Jochum-Bohrmann: Lederer, Hugo . In: Peter Bloch, Sibylle Einholz, Jutta von Simson. Staatliche Museen Preußischer Kulturbesitz (Ed.): Ethos and Pathos. The Berlin School of Sculpture 1786–1914. Exhibition catalog. Gebr. Mann, Berlin 1990, ISBN 3-7861-1597-4 , p. 167-172 .

- Hans Krey: Hugo Lederer, a master of plastic. Schroeder, Berlin 1931.

- Illustrated newspaper . Leipzig, No. 3564 of October 19, 1911.

- Georg Biermann: Hugo Lederer. In: Illustrirte Zeitung. (Leipzig) 139, 1912, pp. 611-614.

- Manfred Höft: Altdammer monuments. In: Pommersche Zeitung. April 20, 1985.

- Rittmeister Bronsart von Schellendorf (arr.): History of the Cavalry Regiment 6 . Schwedt a. O., 1937.

- Dietrich Schubert: Lederer, Hugo. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 14, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1985, ISBN 3-428-00195-8 , p. 41 f. ( Digitized version ).

- Libor Šturc: The sculptor Hugo Lederer and his work: * 1871 Znaim (Czech Republic), † 1940 Berlin. In: Vera Blazek (Ed.): Aachen and Prague - Coronation Cities of Europe (2006–2010). Contributions from the Aachen-Prague cultural association. Volume 3, Prague 2010, ISBN 978-80-254-8857-7 , pp. 54-64.

- Libor Šturc: Hugo Lederer (1871–1940). Sochařské dílo ve sbírce Jihomoravského muzea ve Znojmě (The sculptural work in the collection of the South Moravian Museum in Znojmo) . Thesis. Art history seminar of the Philosophical Faculty of Masaryk University in Brno, Brno 1997.

- Libor Šturc: Bismarckovi face to face. Hugo Lederer v ceskem a moravskem prostredi (Bismarck face-to-face. Hugo Lederer in Bohemia and Moravia) . In: Anna Habanova, Ivo Haban (eds.): Ztracena generace? Lost Generation? German-Bohemian visual artists of the 1st half of the 20th century between Prague, Vienna, Munich and Dresden . Technicka univerzita v liberci, Liberec 2013, ISBN 978-80-7494-025-5 , p. 145-159 .

- Eduard Trier: A monument to the work of Hugo Lederer . In: Wallraf-Richartz-Jahrbuch / Westdeutsches Jahrbuch für Kunstgeschichte . tape 46-47 . Dumont Buchverlag, Cologne 1986, p. 235-246 .

- Bernhard Maaz: Sculpture in Germany - between the French Revolution and the First World War . In: Annual edition of the German Association for Art Studies . Deutscher Kunstverlag, Berlin / Munich 2010.

- Bettina Krogemann: Big in small things … Statuettes by the sculptor Hugo Lederer (1871–1940) . In: Weltkunst . 70th year, issue 7, 2000, p. 1288-1290 .

- Gerold Preiß: Hugo Lederer - from Znaimer Bua to famous German sculptor . In: South Moravian Landscape Council in the Sudetendeutschen Landsmannschaft (Hrsg.): South Moravian Yearbook . 52nd year. C.Maurer, 2003, ISSN 0562-5262 , p. 33–38 , plates 2–9 .

- Henrik Hilbig: Hugo Lederer and the Reichsehrenmal project near Bad Berka . In: South Moravian Landscape Council in the Sudetendeutschen Landsmannschaft (Hrsg.): South Moravian Yearbook . 56th year. C.Maurer, 2007, ISSN 0562-5262 , p. 35–54 , plates 2–7 .

- New works by Hugo Lederer, Die Kunstwelt, German magazine for the fine arts, year 1912/1913, pp. 20-24 ( digitized version )

Web links

- Literature by and about Hugo Lederer in the catalog of the German National Library

- Newspaper article about Hugo Lederer in the 20th century press kit of the ZBW - Leibniz Information Center for Economics .

- hugo-lederer.de

Individual evidence

- ^ Artist: Prof. Hugo Lederer. German Society for Medal Art V., accessed November 25, 2015 .

- ↑ Berlin architecture world. Issue 4 (1902) issue 5, p. 182.

- ^ Gerd Dethlefs: Treasury of Westphalian Art and Forum of Modernism . In: Home care in Westphalia . 21st year, no. 2 , 2008, p. 1–12 ( online at the Westfälischer Heimatbund [PDF; accessed on October 17, 2017]).

- ^ Berlinische Zeitung of state and learned things (Vossische Zeitung)> Art, Science and Literature , March 6, 1909; Evening edition, p. 2; Retrieved April 19, 2015.

- ↑ The German fountain for Buenos Aires . In: German art and decoration . Volume 26, 1910 ( uni-heidelberg.de [PDF; accessed on January 16, 2017]).

- ↑ The Cicerone. Semi-monthly publication for the interests of the art researcher and collector . Volume 3, 1911, p. 606. accessed on June 30, 2016.

- ↑ cf. Postcard from Ms. Anny Lederer to Hugo's sister Poldi Lederer in Vienna: “LP many warm greetings from Aachen! the unveiling was very solemn. SM was in a very good mood. Heinz and Hilde enjoyed the festively decorated city! Anny “ Anny Lederer for the unveiling of the monument to Emperor Friedrich III. in Aachen , accessed on August 25, 2016.

- ^ Wolfgang Pyta: Hindenburg. Rule between Hohenzollern and Hitler. Munich 2007, pp. 135-138.

- ↑ Hans Krey: Hugo Lederer, a master of plastic. Berlin: Schroeder, 1931.

- ↑ Claudia Marcy (ed.): Space for art. Artist studios in Charlottenburg . Edition AB-Fischer, Berlin 2005, ISBN 3-937434-11-9 , pp. 25 .

- ↑ Akademie der Künste, Berlin, Historical Archive Sign. PrAdK 1236. Bl.262 ff

- ↑ Announcement from the Order Pour le mérite ( Memento of the original of May 18, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , accessed June 29, 2016.

- ↑ Libor Šturc: Bismarckovi face to face. Hugo Lederer v ceskem a moravskem prostredi (Bismarck face-to-face. Hugo Lederer in Bohemia and Moravia) . In: Anna Habanova, Ivo Haban (eds.): Ztracena generace? Lost Generation? German-Bohemian visual artists of the 1st half of the 20th century between Prague, Vienna, Munich and Dresden . Technicka univerzita v liberci, Liberec 2013, ISBN 978-80-7494-025-5 , p. 145-159 .

- ↑ Guide to the Modern Gallery in Prague. Prague 1936, pp. 40-43

- ^ Bettina Güldner, Wolfgang Schuster: Das Reichssportfeld. In: Sculpture and Power. Catalog. Berlin 1983, pp. 61-94.

- ↑ Kunst und Künstler 1926, Volume 24, Issue 7, p. 296 (digitized version), accessed on September 1, 2016.

- ↑ The dead of the world war . In: Berliner Tageblatt, August 3, 1924 . ( staatsbibliothek-berlin.de [accessed on January 7, 2017]).

- ^ Henrik Hilbig: The realm memorial near Bad Berka. Creation and development of a monument project for the Weimar Republic. Shaker Verlag, Aachen 2006, ISBN 3-8322-5725-X , pp. 239-261.

- ↑ Federal Archives R / 32 / Archive No. 196, Bl. 92-93

- ^ Georg Kolbe Museum Berlin. Nachlass Georg Kolbe Sign. GK 466, box 13, folder 2, sheet 1 Letter from Ella Kroner dated September 28, 1929 to Georg Kolbe

- ^ German contemporary visual arts and architecture. Exhibition catalog. Berlin 1931 ( hazu.hr [accessed on February 2, 2017]).

- ↑ Bundesarchiv R / 32 archive number 196, pp. 106-107

- ^ Ilonka Jochum-Bohrmann: Hugo Lederer, a German national sculptor of the 20th century . Lang, Frankfurt am Main 1990, ISBN 3-631-42632-1 , p. 164, 238 .

- ↑ Walter van Rossum: Work on the beautiful glow. Why Goebbels forbade art criticism. (PDF) Dossier. Deutschlandfunk, November 18, 2011.pdf, accessed on July 6, 2016.

- ^ Fritz Hellwag: Spring Exhibition of the Prussian Academy. In: Art for All. 49th year, 1933–1934, issue 9, June 1934, pp. 253–260. Quotation Hellwag: “[…] The Hindenburg head by Trumpf and the empty colossal bust of Litzmann by Lederer are only oversized. Konstantin Starck is far too classicistic to model Hitler. [...] What would a professor from the passionate and tragic head of Dr. Goebbels or that of the Führer can get out! […] It was said what was possible. Even the critic could not escape an inexplicable pressure that weighs down on the entire exhibition. Let the artists feel free! ” Https://digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/diglit/kfa1933_1934/0284?sid=206ddc8b2d828823f10102c23d186483

- ↑ Federal Archives R / 9361 / V Archive no. 102652

- ^ Karin Förster: State commissions to sculptors for the Nazi party rally grounds in Nuremberg . In: Magdalena Bushart, Bernd Nicolai, Wolfgang Schuster (eds.): Disempowerment of art. Architecture, sculpture and their instrumentalization 1920–1960 . Frölich and Kaufmann, Berlin 1985, ISBN 3-88725-183-0 , p. 156-182 .

- ^ Historical archive of the Prussian Academy of the Arts, Sign. PrAdK 1226, p. 6 ff

- ↑ Party statistics survey of the NSDAP 1939. Bundesarchiv R / 9361 / I, archive number 1998.

- ^ Prussian Academy of Arts, Historical Archive Sign. PrAdK 0767

- ↑ Hildegard Brenner : End of a bourgeois art institution. The political formation of the Prussian Academy of the Arts from 1933 (= series of the quarterly books for contemporary history, volume 24). Stuttgart 1972, ISBN 3-421-01587-2 , pp. 128-131.

- ^ Letter from the President of the Reich Chamber of Fine Arts to Hugo Lederer, May 6, 1939. Bundesarchiv R / 9361 / I archive number 102652

- ^ Archive of the Prussian Academy of the Arts, Sign.PrAdK 1104-04.3 pp. 136-138

- ↑ When Samuel Beckett was walking through Hamburg's city park in 1936, he thought that the shell limestone block with the reliefs (a stylized lyre surrounded by five seagulls on the left and right sides; in front the name of the poet above a soaring eagle) was the actual monument to see - the distant bronze sculpture of the poet was not known to him. He noted in his diary on November 7, 1936: “Pleasant pale fine day. City hall, gardens, lake, large playground, inmidst of which very wet part. Water tower & planetarium. Parkseering & Bolivarstr. ( Heine monument). Suddenly appalling thirst. " See: Samuel Beckett: Everything depends on so much. The Hamburg chapter from the German Diaries ; October 2 to December 4, 1936, in the original version . Transcribed and with an afterword by Erika Tophoven. Pictures: Roswitha Quadflieg. In: New series of the Raamin Presse, No. 3 . Raamin-Presse, Schenefeld / Hamburg 2003, p. 35 . See also: R. Giordano. The Bertinis S. Fischer Verlag Frankfurt / Main 1982, p. 147.

- ^ Ernst-Adolf Chantelau: "Heinrich Heine's German Monument" by Hugo Lederer. On the trail of the destroyed statue . In: S. Brenner-Wilczek (Ed.): Heine-Jahrbuch 2016 . tape 55 . Springer, Stuttgart 2016, p. 121–143 ( online: cover sheet with photo [PDF]).

- ↑ Ehrich Gaedechens: The Heinedenkmal . In: Walter Hammer [Walter Hammer-Hoesterey] (Ed.): Young people. Monthly magazine for politics, art, literature and life from the spirit of the young generation . 8th year. Young people, Hamburg January 1927, p. 10 : “Liliencron's widow and the Hamburg lyricist Hermann Claudius could be seen among the guests at the unveiling, and again it was Alfred Kerr who found the best words, as the little man, with a voice that does not fit his nature , to the force of his words, shouted: 'Yes, he was a human person - who, whatever he was accused of, never, never, never gave anything away. But he mocked the strongest values of mankind, whipped forward, sang forward. ' Now at last, after the memorial had to swallow the dust of the storage rooms of the Kunsthalle for years, the time was considered ripe and the memorial, which Heine shows, smiling slightly, with his head leaning on his hand, standing on a high pedestal, was torn from the Hidden. It's a shame that it happened so late, but it's good that it happens at all. "

- ^ Alfred Kerr: Richard Strauss, human . 1938. In: Alfred Kerr, works in individual volumes . tape IV . S. Fischer, Frankfurt / Main 2009, ISBN 978-3-10-049508-2 , pp. 268 .

- ^ Völkischer Beobachter. Edition A / North German edition. Volume 47, No. 230 from August 18, 1934.

- ^ Akademie der Künste, Berlin, Historical Archive, Sign. PrAdK I / 297

- ^ Reinhard Müller-Mehlis: Art in the Third Reich . Wilhelm Heyne, Munich 1976, p. 17-18,163 . Under the direction of the painter Adolf Ziegler , the commission included (quote): “The painter and writer Wolfgang Willrich, author of the inflammatory pamphlet 'The cleansing of the art temple. An art-political campaign pamphlet for the recovery of German art in the spirit of the Nordic kind ', 1937, and other racist books; the new director of the Folkwang Museum in Essen and later head of the Reich Ministry of Education, the art historian Klaus Graf von Baudissin; the painter and draftsman Hans Schweitzer, since 1936 on the Presidential Council of the Reich Chamber of Fine Arts, who was better known under the pseudonym 'Mjölnir' - and a representative of the Reich Ministry of Education (and) Dr. Walter Hansen ”. It was his son, Heinz Lederer, who was the “Landesleiter Berlin” of the Reich Chamber of Fine Arts as a censor on behalf of (Hans Jürgen Meinik. The studio community at Klosterstrasse within the National Socialist art and cultural policy. In: Akademie der Künste (ed.) Exhibition catalog . Ateliergemeinschaft Klosterstrasse Berlin 1933–1945. Artists during the National Socialist era. Edition Hentrich.Berlin. 1994, pp. 12–39)

- ^ Academy of the Arts, Berlin, Historical Archive, Sign. PrAdK I / 079

- ↑ Magdalena Bushart: Arno Breker (born 1900) - art producer in the service of power. In: Skulptur und Macht, Catalog Berlin 1983, pp. 155–158.

- ↑ Hildegard Brenner: End of a bourgeois art institution. The political formation of the Prussian Academy of the Arts from 1933 . (= Series of the quarterly books for contemporary history. Volume 24). Stuttgart 1972, ISBN 3-421-01587-2 , pp. 153-154.

- ↑ Akademie der Künste Berlin, Historical Archive Sign. PrAdK 1109, p. 145

- ^ Ernst-Adolf Chantelau: The bronze statues of Tuaillon, Thorak, Klimsch and Ambrosi for Hitler's garden . A contribution to the topography of the New Reich Chancellery by Albert Speer. Books on Demand, Norderstedt 2019, ISBN 978-3-7494-9036-3 .

- ↑ Akademie der Künste Berlin, Historical Archive Sign. PrAdK Pers BK 314. Quote: “It was a particular pleasure for him that one of his favorite works, the Pavlovna, which feeds a deer, is in the garden of the New Reich Chancellery, ie in the immediate vicinity of the Führer, took place. How much he was attached to this work, we witnessed in the academy when he never got tired of putting the work in a different, even more favorable light in our exhibition, and of making repeated attempts with different tones of the sculpture. "

- ^ Fritz Hellwag: Hugo Lederer † August 1, 1940 . In: Art for All . tape 56 , no. 2 , 1940, p. 25–28 ( online [accessed August 25, 2016]).

- ↑ Robert Scholz: Hugo Lederer to the memory . With 4 full-page illustrations (Peyrouse bust, archer, fencer, crouching, wrestler). In: Art in the German Empire . Edition A. 4th year, No. 12 , 1940, p. 368-373 .

- ^ Akademie der Künste, Berlin, Historical Archive Sign. PrAdK 1133

- ↑ Funeral service for Professor Hugo Lederer . Deutsche Allgemeine Zeitung, August 6, 1940.

- ^ Völkischer Beobachter (Berlin edition). No. 219 of August 6, 1940, p. 5. Funeral service for Professor Dr. Hugo Lederer . Quote: “Reich Minister Dr. Goebbels, the Prussian Academy of the Arts in Berlin, the Academy of the Arts in Munich and the Vienna Academy of the Arts had wreaths laid on the coffin as the last honor for the deceased. "

- ^ Akademie der Künste, Berlin, Historical Archive Sign. PrAdK I / 079

- ^ Felix Bornemann : Hugo Lederer, his life and his work. Geislingen / Steige: South Moravia. Landscape Council, 1971.

- ^ Claudia Wedepohl: Walpurgis Night on the Stintfang. Aby Warburg art-political. In: J.Schilling (edit.): The Bismarck Monument in Hamburg 1906-2006. (= Workbooks on the preservation of monuments in Hamburg. No. 24). Editor of the Hamburg Cultural Authority / Monument Protection Office, 2006, pp. 60–68, quoted by Aby Warburg: “It is now extremely interesting to observe and of downright epoch-making significance that in the award-winning design by Lederer and Schaudt, the victorious penetration into a concentrated / simplified formal language , in which architecture and sculpture can reflect on their own means, all the more closely because there is also a second, non-award-winning design by the same Lederer that shows him still in conflict with the older tradition of decorative patriotic exhibits. "Warburg Institute Archives, III.27.2.3 [1]

- ^ Claudia Wedepohl: Walpurgis Night on the Stintfang. Aby Warburg art-political . In: Hamburg Cultural Authority / Monument Protection Office (ed.): The Bismarck Monument in Hamburg 1906–2006. Edited by J. Schilling. No. 24 , 2006, pp. 62-68 .

- ^ MO (Max Osborn): Hugo Lederer. For his 60th birthday on November 16 . In: Vossische Zeitung . November 15, 1931, p. 22 .

- ^ Paul Westheim : Louis Tuaillon . In: Weser newspaper. Bremen, March 4, 1919; quoted from Waldemar Grzimek. German sculptor of the twentieth century . Heinz Moos Verlag, Munich Graefelfing 1969, p. 33.

- ↑ Hans Krey: Hugo Lederer. A master of sculpture , Berlin 1931, p. 73.

- ↑ Der Cross Section 1925, Volume 5, Issue 9, pp. 817–818, Lederer contra Kolbe 1925 , accessed on June 29, 2016.

- ^ Art and artists. 1925, p. 452. (digitized version )

- ^ Akademie der Künste, Berlin, Historical Archive Sign. PrAdK I / 127

- ↑ Invictis victi victuri. The University's Fallen Memorial - Black & White & Red unveiling ceremony . In: Berliner Volkszeitung . July 10, 1926, ZDB -ID 27971740 , p. 2 ( Berliner Volkszeitung. July 10, 1926 [accessed October 5, 2016]).

- ^ Aby Warburg: Dürer and the Italian antiquity. (PDF) Lecture 1905, accessed on June 29, 2016.

- ↑ Albrecht Dürer, Death of Orpheus , accessed on June 29, 2016.

- ↑ Fallen Monument Berlin University, accessed on August 27, 2016

- ↑ Arno Breker: In the radiation field of events . KW Schütz, Preußisch Oldendorf 1972, p. 90. Quote: “'You work according to antiquity,' stated Hitler; I contradicted: 'No, my Führer, my two bronzes in the Reichssportfeld are portraits of outstanding athletes.' "

- ↑ Gabriele Huber: Dachshunds, deer, bears with the double sigrune: considerations on the program of the porcelain manufactory Allach-München GmbH . In: Berthold Hinz (Ed.): Nazi art: 50 years later . Jonas Verlag, Marburg 1989, ISBN 3-922561-87-X , p. 55-79 .

- ↑ Uwe M.Schneede: The history of art in the 20th century. From the avant-garde to the present. CH Beck, Munich 2001, ISBN 978-3-406-48197-0 .

- ↑ http://marckshb.blogspot.de/2015/02/arbeit-am-tolken-nachlass.html , accessed on December 20, 2017

- ↑ Lederer, Hugo . In: Reich manual of the German society. The handbook of personalities in words and pictures . tape 2 . Deutscher Wirtschaftsverlag AG, Berlin 1931, p. 1084-1086 .

- ↑ Report of the local news from Znojmo from September 20, 2011 ( Memento of the original from July 6, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , accessed July 6, 2016.

- ^ Autumn exhibition at the Prussian Academy, Berlin . In: Art for All . 56th volume, issue 3, December 1940, appendix, p. 2 .

- ^ R (obert) Sch (olz): Hugo Lederer, the creator of the Hamburg Bismarck monument, has died . In: Völkischer Beobachter . August 2, 1940. Quote: “In Berlin yesterday the well-known sculptor Prof. Dr. hc Hugo Lederer died at the age of 69. Hugo Lederer was not only one of the most important sculptors of the Second Reich, but his achievements have had an exemplary effect up to the present day, even if a serious illness overshadowed the work of his last years ... "

- ^ Ilonka Jochum-Bohrmann: Hugo Lederer, a German national sculptor of the 20th century. Lang, Frankfurt am Main 1990, ISBN 3-631-42632-1

- ^ Dietrich Schubert: Lederer, Hugo . In: New German Biography . tape 14 , 1985, pp. 41 ( deutsche-biographie.de ).

- ↑ Dietrich Schubert: "Now where?" The "German memorial" for Heinrich Heine . In: Heine yearbook . Volume 28, 1989, p. 52 .

- ^ Ilonka Jochum-Bohrmann: Lederer, Hugo . In: Peter Bloch, Sibylle Einholz, Jutta von Simson. Staatliche Museen Preußischer Kulturbesitz (Ed.): Ethos and Pathos. The Berlin School of Sculpture 1786-1914. Exhibition catalog. Gebr. Mann, Berlin 1990, ISBN 3-7861-1597-4 , p. 167-172 . Quote: "He often expressed his preference for heroic figures, for athletic male bodies, for example in the 'Peyrouse' (around 1903 [...]), in the 'Ringer' (1908–1911), the 'Sieger' sports monument (around 1927), of the runners group (before 1929). The National Socialist cultural bearers recognized in such figures Lederer a forerunner of their own artistic will. The portraits of Richard Strauss (1908), Heinrich Heine (1913), or the smaller studio creations illustrate that Lederer also had other artistic abilities. "

- ↑ Robert Scholz: Hugo Lederer to the memory . In: Art in the German Empire. Edition a . With 4 full-page illustrations ('Peyrouse bust', 'archer', 'fencer', 'crouching', 'wrestler'). 4th volume, 12 (December), 1940, p. 368-373 . Quote: “Lederer's three-dimensional figures are not imitations of nature or the definition of a random optical impression, but are independent symbols of a lofty ideal of physical existence, created from an absolute three-dimensional imagination and the knowledge of plastic architecture. A great technical and formal ability and an innate sense for the organic structure according to the law of an architectural harmony of the forms in space are the foundations on which the art of Lederer builds. […] Hugo becomes the upcoming monumental epoch of the new German sculpture Recognize Lederer not only as a great artistic figure of his time, but also in these [the works shown] and other works as a forerunner of their own will. "

- ↑ berlin.de

- ↑ Kronthal-Brunnen 2015 ; Retrieved July 7, 2016.

- ↑ Max Schmid (ed.): One hundred designs from the competition for the Bismarck National Monument on the Elisenhöhe near Bingerbrück-Bingen. Düsseldorfer Verlagsanstalt, Düsseldorf 1911. (n. Pag.)

- ↑ State Conservator Rhineland Monuments Directory. 1.2 Aachen, other parts of the city. Edited by Volker Osteneck with the assistance of Hans Königs . Status: 1974–1977. Rhineland Cologne, 1978, p. 34.

- ^ Max Schmid: Kaiser Friedrich monument in Aachen . In: German Art and Decoration , Vol. 29, Oct. 1911 – March 1912, pp. 208–210.

- ↑ bpk-images No. 10026042 accessed on August 31, 2016.

- ^ Georg Pahl: A monument by Hugo Lederer Diana at the Brandenburg Gate in Berlin. July 1926, Retrieved July 30, 2019 .

- ↑ Merkur-Brunnen 2012, accessed July 7, 2016

- ↑ Kathrin Hoffmann-Curtius : The war memorial of the Berlin Friedrich Wilhelms University 1919–1926: Exegesis of victory for defeat . In: Yearbook for University History. 5, 2002, pp. 87-116.

- ↑ Christian Welzbacher: The state architecture of the Weimar Republic . Lukas Verlag, Berlin 2006, ISBN 978-3-936872-62-0 , pp. 63 ff .

- ↑ Aureus Cemetery Mainz No. 12, German Court of Honor. (No longer available online.) In: Where they rest. wo-sie-ruhen.de, archived from the original on June 15, 2016 ; accessed on June 28, 2016 . Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ File: TrajanXanten.jpg. Trajan statue in Xanten, overall picture. Accessed July 31, 2019 .

- ^ Brunnenanlage Berlin Arnswalder Platz around 1934 , accessed on June 29, 2016;

- ↑ Fertility Well 2010 ( Memento of the original from July 7, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link has been inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , accessed July 7, 2016.

- ↑ Anna Pavlovna, feeding a deer . Plaster model , accessed on July 13, 2016. Cf. also Hugo Lederer. Memories of Anna Pavlova. In: The dance. Monthly magazine for dance culture. Volume IV (1931), Volume 3, pp. 6-7.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Lederer, Hugo |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | German sculptor |

| DATE OF BIRTH | November 16, 1871 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Znojmo |

| DATE OF DEATH | August 1, 1940 |

| Place of death | Berlin |