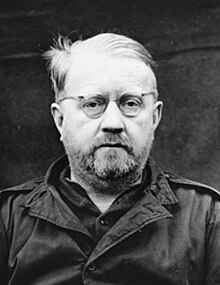

Gerhard Rose

Gerhard August Heinrich Rose (born November 30, 1896 in Danzig ; † January 13, 1992 in Obernkirchen ) was head of the Department for Tropical Medicine at the Robert Koch Institute and consultant hygienist at the head of the Air Force's medical services during the Nazi era . Because of his involvement in human experiments in the Buchenwald concentration camp , he was sentenced to life imprisonment at the Nuremberg medical trial . After her release from prison in 1955, Rose was awarded pension rights as a civil servant in 1963 following disciplinary proceedings .

Education and early employment

As the son of a senior post councilor, Rose attended high schools in Stettin, Düsseldorf, Bremen and Breslau. After graduating from high school, he began to study medicine at the Kaiser-Wilhelms-Akademie for military medical education . In 1914 he became active in the Pépinière Corps Saxonia. He moved to the Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität Berlin and the Schlesische Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität Breslau . Rose passed the medical state examination on November 15, 1921 with the grade "very good", received the license to practice medicine on May 16, 1922 and received her doctorate on November 20, 1922 with the grade "Magna cum laude". Rose's training was interrupted from 1914 to 1918 when she participated in the First World War. In 1921 he participated as a member of the Freikorps Roßbach, according to his own account, in the "defense against the Polish invasion of Upper Silesia" . In 1922 he was one of the founding members of the Greater German Workers' Party , a cover organization of the NSDAP, which was banned in Prussia at the time . In 1923 he also became a member of the Corps Franconia Hamburg, which was relocated to Hamburg by the KWA.

Between 1922 and 1926 Rose worked as an assistant doctor at the Robert Koch Institute in Berlin, the Hygiene Institute in Basel and the Anatomical Institute of the University of Freiburg im Breisgau . According to contradicting statements, he ran a private practice in Heidelberg from 1926 or worked as an assistant at the surgical clinic of the Ruprecht-Karls-Universität Heidelberg .

Rose left Germany in 1929 to work in China as a medical advisor to the Kuomintang government. In December 1929, he was appointed director of the National Health Service in Chekiang , and he was also a public health advisor to the Interior Minister of Chekiang. Rose's time in China was interrupted by extensive study visits to Europe, Asia and Africa. On November 1, 1930, Rose joined the NSDAP ( membership number 346.161).

In the run-up to the Sino-Japanese War , Rose returned to Germany in September 1936, was appointed professor and, on October 1, took over the management of the Department of Tropical Medicine at the Robert Koch Institute in Berlin. From the summer semester of 1938 Rose held lectures and exercises on tropical hygiene and medicine at the Berlin University. On February 1, 1943, Rose was appointed Vice President of the Robert Koch Institute.

In 1939 Rose joined the Air Force's medical services , and in the same year he was a member of the Condor Legion in Spain. In 1942 he was appointed consultant hygienist and tropical medicine for the Air Force's medical services. By the end of the war, Rose had attained the rank of general physician .

Rose married in August 1942. The marriage resulted in a child.

Malaria trials in psychiatry

Rose's predecessor as head of department at the Robert Koch Institute was Claus Schilling . Rose continued Schilling's malaria trials, which were mainly carried out on psychiatric patients. In 1917 the Austrian psychiatrist Julius Wagner-Jauregg succeeded in treating progressive paralysis with the help of malaria pathogens . This type of malaria therapy was also used by Rose on schizophrenics .

Between 1941 and 1942 Rose tested new anti-malarial drugs for the IG Farbenindustrie , Leverkusen plant. Malaria attempts with Rose's participation are documented for the Saxon state sanatorium and nursing home in Arnsdorf . By July 1942, a total of 110 patients had been infected by mosquito bites. In a first series of experiments, in which 49 people were included, four people were killed. The experiments in Arnsdorf took place at the time of the National Socialist murders, Action T4 . Test subjects were transferred to other institutions and killed there. By his own account, Rose went to one of the main organizers of Aktion T4, Viktor Brack , and got his promise that test subjects would be excluded from the relocation.

Rose was still in contact with his predecessor Claus Schilling, who from January 1942 carried out human experiments in the Dachau concentration camp in order to develop a vaccine against malaria. There he took part in the distress conference (Dachau experiments) in October 1942 .

Typhus vaccine trials in concentration camps

The ghettoization of the Jews and the conditions in the prisoner-of-war camps led to the outbreak of typhus epidemics in the areas occupied by Germans in the east . According to Rudolf Wohlrab , who worked at the Warsaw Hygiene Institute and who Rose met in Warsaw, the main spreaders of typhus in the Generalgouvernement were “the vagabond Jews from the Jewish residential area of Warsaw” . In the autumn of 1941, the disease also spread to the Reich territory as a result of Wehrmacht vacationers and forced laborers who were deported to the German Reich . In December 1941, several meetings were held between representatives of the Wehrmacht, manufacturers and representatives of the Reich Ministry of the Interior , responsible for health issues, in search of a suitable vaccine . Since the vaccines from several manufacturers were new and no experience was yet available about their protective effects, human experiments were agreed in the Buchenwald concentration camp , which began in January 1942. The tests were subordinate to the hygiene institute of the Waffen-SS under Joachim Mrugowsky , Erwin Ding-Schuler was the test director on site in Buchenwald .

On March 17, 1942, Rose and Eugen Gildemeister visited the experimental station in Buchenwald concentration camp. At this point in time, 150 inmates had been infected with typhus, 148 of whom were diagnosed with the disease. In total, tests with typhus were carried out on over 1000 prisoners in Buchenwald, at least 250 of whom died. According to a medical report issued in 1957, one survivor suffered from total weakness, memory loss, obesity tendency, anxiety, insomnia, persistent headache, dizziness, loss of all hair, and impotence.

At the 3rd working conference of the consulting physicians of the Wehrmacht, Ding-Schuler gave a lecture in May 1943 under the title On the result of testing various typhus vaccines against classic typhus , in which he - camouflaging the experiments under the term lightning rod - their results lectured. Rose, who attended the meeting and had briefed on the nature of human experiments, objected to the nature of human experiments before the meeting. According to later information from one present, "thereupon the participants in the meeting whispered quietly [...] that these were probably concentration camp attempts." Rose's objection was later confirmed by Eugen Kogon independently of the conference participants . As a prisoner, Kogon was Ding-Schuler's doctor's clerk, who in Buchenwald repeatedly expressed his displeasure with Rose's intervention.

Regardless of his protest in May 1943, Rose turned to Joachim Mrugowsky from the hygiene institute of the Waffen-SS on December 2, 1943 with the request to carry out another series of experiments with a new typhus vaccine in the Buchenwald concentration camp . Enno Lolling , Head of Office D III (Sanitary and Camp Hygiene) in the SS Economic and Administrative Office , approved the series of experiments on February 14, 1944, for which "30 suitable gypsies " were to be transferred to Buchenwald. The test series was carried out between March and June 1944, six of the 26 infected prisoners died.

According to later information from Rose's superior, Oskar Schröder , Rose supervised typhus tests carried out by the professor of hygiene at the University of Strasbourg , Eugen Haagen , in the Natzweiler concentration camp . Haagen complained in writing to Rose on October 4, 1943 that he lacked suitable prisoners to carry out infection experiments on vaccinated people. On November 13, 1943, the SS main office in Haagen transferred 100 prisoners. According to information in a letter from Hague to Rose on November 29, 18 prisoners died on the transport. According to Haagen, twelve of the survivors were suitable for the experiments, provided they were fed for two to three months in such a way that their body condition corresponded to that of soldiers. Rose replied to Haagen on December 13th: He asked Haagen to also test the vaccine in the Natzweiler concentration camp, for which - as requested by Rose on December 2nd - a series of experiments was to be carried out in the Buchenwald concentration camp.

At the beginning of 1944, the Air Force Institute for Military Hygiene, headed by Rose, was relocated to the Pfafferode State Sanatorium near Mühlhausen . In the Pfafferode asylum, headed by Theodor Steinmeyer , patients were murdered during the second phase of the National Socialist murders, Aktion Brandt , through food withdrawal and drug overdosing. In terms of personnel, the institute was largely identical to the Robert Koch Institute; the employees had been drafted into the Air Force. According to the received organizational plans, there were departments in Pfafferode for malaria therapy, pest biology and DDT preparations, among other things . Probably no malaria tests were carried out on patients in the institution.

Defendant in the Nuremberg medical trial

At the end of the war, Rose was captured by Allied troops on May 8, 1945 .

Indications of the involvement of Air Force doctors in the human experiments in concentration camps emerged in the Nuremberg trial of the main war criminals . Hermann Göring , Commander-in-Chief of the Air Force , was also charged here . According to the medical historian Udo Benzenhöfer , the allied investigations also started with those directly involved in the experiments and advanced "by tracing the chain of responsibility to the higher-ranking and highest-ranking defendants". Rose was charged with seven other Air Force doctors in the Nuremberg medical trial. The main focus of the charges against Rose were the typhus experiments in the Buchenwald and Natzweiler concentration camps. The charge dropped the charge of having also been involved in experiments with epidemic jaundice in the Sachsenhausen concentration camp . In the course of the trial, Rose was also accused of supporting Claus Schilling's attempt at malaria in the Dachau concentration camp, in particular by sending Anopheles mosquitoes. This was not taken into account in the judgment, as these attempts were not mentioned in the indictment against Rose.

Rose was distinguished from the other defendants in his intellectual nature and extensive medical experience. Based on his international experience, in his testimony between April 18 and 25, 1947, he drew numerous comparisons between the experiments in the German concentration camps and experiments that foreign researchers had carried out on people. Rose referred to experiments that the American tropical medicine doctor Richard Pearson Strong had carried out to research beriberi disease in Manila on people sentenced to death, in which a person died. He assumed that the experiments in the Buchenwald concentration camp "should be carried out on criminals sentenced to death." The former prisoner Eugen Kogon (1903–1987) , who was summoned as a witness in Nuremberg, contradicted this : to find volunteers in Buchenwald concentration camp. The test subjects were chosen at will by the camp management, equally from the groups of political prisoners, homosexuals , professional criminals and anti-social groups . He is not aware of a single case in which there has been a death sentence. During the interrogation, the prosecution presented as evidence Rose's letter to Joachim Mrugowsky dated December 2, 1943, in which Rose requested another series of experiments in Buchenwald. Rose then compared himself to a lawyer who is an opponent of the death penalty and who campaigns for its abolition in professional circles and vis-à-vis the government: “If he does not succeed in doing that, he still remains in the profession and in his environment, and he can under certain circumstances even be forced to pronounce such a death sentence himself, although he is fundamentally an opponent of this institution. "

On August 19, 1947, Rose was found guilty and sentenced to life in prison . In the grounds of the judgment, the court assumed that Rose may initially have had concerns about the experiments in the concentration camps. However, he overcome the concerns and then knowingly, actively and approvingly participated in the trial program. There is overwhelming evidence against Rose, the court said. The cross-examination showed that he himself was aware of his wickedness . The reasons for the judgment also said:

The Tribunal ruled that the Defendant Rose was a main perpetrator and accomplice, ordered, promoted, admitted his consent and was connected with plans and undertakings that involved medical experiments on non-Germans without their consent, in the course of which murder was committed , Brutalities , atrocities , tortures, atrocities and other inhumane acts have been committed. To the extent that these criminal acts were not war crimes , they were crimes against humanity .

Prison Service and Campaign for Release

On January 31, 1951, the sentence was reduced to fifteen years in prison by the American High Commissioner John Jay McCloy . The prison director found Rose trustworthy and reliable, called him a "loner," and described his attitude toward the prison staff and inmates as equally excellent. Regarding Rose's attitude towards his conviction, it said: "He feels that he was only carrying out the orders of his superiors and that the punishment was too severe." The detention had "increased his bitterness towards his former superiors." Rose was born on June 3, 1955 as the last of those sentenced to prison terms in the medical trial, released from the Landsberg war crimes prison .

Rose's imprisonment was accompanied by various efforts to obtain his early release, the focus of which was on Rose's wife and Ernst Georg Nauck , director of the Hamburg Bernhard Nocht Institute . On September 29, 1950, the Free Association of German Hygienists and Microbiologists turned to John Jay McCloy with a request for Rose's release: His great professional experience and previous achievements indicated that “he will give many valuable achievements to science and humanity, if he will finally, after more than five and a half years imprisonment, be returned to his profession and work. ”In the Hamburg weekly newspaper Die Zeit appeared under the heading Unjustly in Landsberg. A word for the researcher and doctor Gerhard Rose an article by Jan Molitor .

In addition to his arguments in the medical process, Rose justified a petition for clemency from November 2, 1953 by stating that those actually responsible for the typhus experiments had not been held responsible and in some cases had meanwhile been accepted into the American government service. The pardon was refused because Rose had not applied for an early release on word of honor under the American "parole trial", although this would have been possible since May 8, 1950. According to the “parole procedure”, part of the prison term could be spent outside the prison under conditions and supervision of an officer. Failure to comply could result in return to prison. Although it was not formally a pardon, the “parole trial” was equivalent to an act of mercy, insofar as it was applied to convicted German war criminals in the 1950s. From Rose's point of view, the "parole trial" "carefully upheld the fiction of treatment as a criminal in its form" and was "additionally tightened by political clauses that are alien even to the penal system against common criminals in the United States of America."

Disciplinary proceedings

After his release, Rose pursued his rehabilitation. As so-called " 131s ", civil servants who had worked for the National Socialist state could also be admitted as civil servants in the Federal Republic of Germany. Disciplinary proceedings were initiated against Rose in May 1956 because of an official offense , and Federal Disciplinary Chamber VII in Hamburg acquitted him on October 24, 1960 . According to the Disciplinary Chamber, Rose's behavior during World War II did not cause Germany's reputation to suffer in the world. The same applies to the reputation of German doctors in the world: "If the German medical profession claims that they did not approve and promote the inhuman methods of National Socialism in their entirety, then they can rightly appeal to the accused, who manly stood up for the preservation of the medical ethos and a humane disposition, even when it was associated with a personal danger for him. ”One of the experts heard by the court as witnesses was Rudolf Wohlrab , who from 1940 onwards in Warsaw on human experiments Had undertaken typhus and was in contact with Rose during this time, as well as Ernst Georg Nauck, who had campaigned for Rose's early release from prison.

The conduct of negotiations by the disciplinary chamber met with criticism from Alexander Mitscherlich . Mitscherlich was interrogated as a witness on October 21, 1960, because he had published the collection of documents, Science Without Humanity, on the Nuremberg Doctors' Trial. According to Mitscherlich, the chamber's collection of documents was not available. He, Mitscherlich, was held up to the testimony of an SS judge for at least a quarter of an hour, in which the Buchenwald concentration camp was described as "a place of extreme cleanliness, well-tended garden paths with lots of flowers, the greatest possible order". The chairman explained to Mitscherlich, "that he himself was active in the judiciary in the 3rd Reich and that he was never made a condition of any kind that would have restricted his freedom." Compared to the Hessian State Secretary for Justice, Erich Rosenthal-Pelldram , Mitscherlich expressed his impression that he “had to answer before a well-camouflaged National Socialist court for the publication of 'Science without Humanity'” and spoke of an “attempt to lie about the past in an almost fantastic way with the help of a court case. "

On January 8, 1962, the Federal Disciplinary Court overturned the Hamburg judgment and referred the proceedings to the Federal Disciplinary Chamber X in Düsseldorf for re-trial. The reason was the refusal of the Hamburg Chamber to use Erwin Ding-Schuler's diary as evidence. When Buchenwald was liberated, the diary had been secured by Eugen Kogon , prisoner in Buchenwald and doctor clerk Ding-Schuler, and given to the American troops. The defense attorneys at the medical trial challenged the use of the diary as evidence, and it incriminated five of the defendants. According to investigations by writing experts, it was probably not a day-to-day book, but a subsequent fair copy, the entries of which were countersigned by Ding-Schuler. The information contained was confirmed in the medical process through statements and numerous other documents. Contrary to this, the prison functionary Arthur Dietzsch claimed in statements for the defense in the Nuremberg medical trial that he had destroyed the diary at the end of the war. Dietzsch worked closely with Ding-Schuler and was himself involved in the typhus tests in Buchenwald. Dietzsch was charged in the Buchenwald trial and sentenced to 15 years in prison. According to Gerhard Rose, he was imprisoned with Dietzsch in the Landsberg war crimes prison. Dietzsch had been questioned in the Hamburg trial; the disciplinary body considered his statements to be reliable. On October 3, 1963, Rose was acquitted by the Düsseldorf Disciplinary Chamber on appeal. With regard to Ding-Schuler's diary, the verdict said: “The attempts that have now been made to obtain the diary were unsuccessful. The diary has not been put on file. A new request for evidence to refer to the diary has not been made. ”With the second judgment becoming final, Rose was able to draw a pension from his activity as a civil servant.

Retirement

After his release from prison in 1955, Rose received the Band des Corps Brunsviga Göttingen as a member of the two KWA Corps in 1956 . In 1958 he took up a job at the Heye glassworks . He became managing director of the bottle factory in Obernkirchen , and he was also on the board of several associations in the glass industry . As a member of Silent Aid , he got involved with convicted National Socialist criminals.

The German Society for Military Medicine and Military Pharmacy (DGWMP) awarded Rose the Paul Schürmann Medal in July 1977. The award document states that Rose had "made an outstanding contribution to military hygiene issues." His activities in China and during World War II as a consultant hygienist for the Air Force were highlighted. A tribute to Rose in the Deutsches Ärzteblatt on her 80th birthday named the fight against schistosomiasis, smallpox, cholera, plague, typhus, relapsing fever, epidemic stiff neck and worm diseases, hepatitis epidemica, malaria and papataci fever as the main areas of research. According to the Ärzteblatt , Rose was acquitted in 1964 for "proven innocence". The most beautiful and best award for Rose was "the awareness that I was always" there "for those injured in the wars, for the inhabitants of remote and disease-threatened areas," according to the Ärzteblatt.

Rose endeavored to restore his reputation until the end of his life. In 1981 he asked a Hamburg lawyer to issue a cease and desist declaration . The lawyer had previously stated in a letter to the editor that Rose had become known “through his human experiments during the Nazi era”. In 1989 Rose turned to the Spiegel publisher, Rudolf Augstein , because he felt defamed by a depiction of the mirror . In the letter, Rose described Ding-Schuler's diary presented in Nuremberg as a "falsification of purpose" and called Eugen Kogon a "professional witness" whose lies could be recognized by any reasonable person. At the same time, he promoted the documentation Der Fall Rose , which was created in 1988 by the historical revisionist contemporary history research center Ingolstadt . According to the publisher , the book published by Mut Verlag wanted to make a contribution to clearing up a “miscarriage of justice” and in particular to counter the documentation of the medical trial by Alexander Mitscherlich .

In 1960, in the preface to the new edition of Medicine Without Humanity, Alexander Mitscherlich came to the following assessment of Rose and his defense strategy in the Nuremberg Doctors Trial:

Where Strong sought protection against misery and death of the nature of a natural disaster, researchers like the Defendant Rose operated in the thicket of inhuman methods of a dictatorship to maintain its futility. It is quite easy to see through the fact that comparisons such as the sophistical confusion spun by Rose should create confusion for the purpose of his defense. Even so, it does not matter what the arguments of the apology are. Here they came from the wealth of experience of a researcher from "normal" times with their emergencies, and from there, ignoring the markings of the borders, he strides further into the realm of political catastrophe as if everything were the same. The motivation of the war, the most brutal inhumanity of its goal, the planned genocide, is thus taken out of the game. For anyone who does not follow the cheat game closely, the mindfully convincing thought remains: the best of the nation are in danger; it is better to sacrifice death-row criminals than they are. […] Nothing in men like Rose indicates resistance to the special war goal of not only defeating other peoples, but depriving them of the right to call themselves human beings. Nothing betrayed any real sympathy for the "best of the nation" who could only be helped by ending the war as quickly as possible. Nobody could really have forced them to experiment on defenseless victims of the terrorist regime. What they finally clung to is a ghost, the ghost of their honor, the echoes of human dignity that they lost the moment they made the pact with the monster.

literature

- Angelika Ebbinghaus (ed.): Destroying and healing. The Nuremberg Medical Trial and its Consequences. Aufbau-Taschenbuch-Verlag, Berlin 2002, ISBN 3-7466-8095-6 .

- Klaus Dörner (ed.): The Nuremberg Medical Trial 1946/47. Verbal transcripts, prosecution and defense material, sources on the environment. Saur, Munich 2000, ISBN 3-598-32028-0 ( index volume ) ISBN 3-598-32020-5 (microfiches).

- Ulrich Dieter Oppitz (edit.): Medical crime in court. The judgments in the Nuremberg Doctors Trial against Karl Brandt and others as well as from the trial against Field Marshal Milch. Palm and Enke, Erlangen 1999, ISBN 3-7896-0595-6 .

- Alexander Mitscherlich (ed.): Medicine without humanity. Documents of the Nuremberg Doctors' Trial. 16th edition, Fischer Taschenbuch, Frankfurt am Main 2004, ISBN 3-596-22003-3 .

- Christine Wolters: Human experiments and hollow glass containers out of conviction. Gerhard Rose - Vice President of the Robert Koch Institute. In: Frank Werner (Hrsg.): Schaumburg National Socialists. Perpetrators, accomplices, profiteers. Publishing house for regional history, Bielefeld 2009, ISBN 978-3-89534-737-5 , pp. 407-444.

Web links

- Nuremberg Trials Project Documents on Gerhard Rose from the Nuremberg Medical Trial (partly in English)

- Literature by and about Gerhard Rose in the catalog of the German National Library

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c Kösener Corpslisten 1960, 63 , 189; 60 , 545; 40 , 1096

- ↑ Biographical information on Rose in: Dörner, Ärzteprozess , p. 136 (indexing volume), p. 8 / 03112ff. (Appeal from November 2, 1953) p. 8 / 03174ff. (Judgment of the Federal Disciplinary Chamber VII of October 24, 1960 (Az. VII VI 8/60)). Ernst Klee : Auschwitz, Nazi medicine and its victims. 3rd edition, S. Fischer, Frankfurt am Main 1997, ISBN 3-10-039306-6 , p. 126.

- ↑ Request for grace of November 2, 1953 , in: Dörner, Ärzteprozess , p. 8/03114. See also: Hellmann: Gerhard Rose 80. In: Deutsches Ärzteblatt 4/1977, p. 261.

- ↑ Annette Hinz-Wessels: The Robert Koch Institute in National Socialism. Kulturverlag Kadmos, Berlin 2008, ISBN 978-3-86599-073-0 , p. 38.

- ↑ a b Dörner, Ärzteprozess , p. 136.

- ^ Judgment of the Federal Disciplinary Chamber VII of October 24, 1960 (Az. VII VI 8/60) , in: Dörner, Ärzteprozess , p. 8/03174; see also: Klee, Auschwitz , p. 126.

- ^ Dörner, Doctors' Trial ; P. 136.

- ↑ Klee, Auschwitz , pp. 116 f., 126 f.

- ↑ On Arnsdorf and the figures mentioned see Klee, Auschwitz , p. 127 ff.

- ↑ In an interview in 1985, see Klee, Auschwitz , p. 129.

- ↑ example: Letter from Claus Schilling to Gerhard Rose from April 4, 1942 at the Nuremberg Trials Project ( Memento from July 15, 2012 in the web archive archive.today ) (Nuremberg document NO-1752). Letter from Gerhard Rose to Claus Schilling dated July 27, 1943 at the Nuremberg Trials Project ( Memento from July 18, 2012 in the web archive archive.today ) (Nuremberg document NO-1755)

- ↑ a b Ernst Klee: The dictionary of persons on the Third Reich. Who was what before and after 1945, Verlagsgruppe Weltbild GmbH, licensed edition, Augsburg, 2008, p. 507

- ↑ Klee, Auschwitz , p. 287 f.

- ^ Rudolf Wohlrab: Typhus control in the Generalgouvernement. Münchner Medizinische Wochenzeitschrift, May 29, 1942 (No. 22), p. 483 ff. Quoted from: Klee, Auschwitz , p. 287.

- ↑ Klee, Auschwitz , p. 292. The entry in the diary of the test station at the Nuremberg Trials Project ( Memento from July 17, 2012 in the web archive archive.today ) (Nuremberg Document NO-265, p. 3)

- ^ The numbers in Klee, Auschwitz , p. 293

- ↑ Report of the medical officer of the German Embassy in Paris on a French police officer, quoted in Klee, Auschwitz , p. 293

- ↑ Mitscherlich, Medicine , p. 126; Klee, Auschwitz , p. 310 f.

- ^ Walter Schell's affidavit of March 1, 1947, quoted from: Mitscherlich, Medizin , p. 126. Schell's statement in English translation at the Nuremberg Trials Project ( Memento from July 13, 2012 in the web archive archive.today )

- ↑ Klee, Auschwitz , p. 311

- ↑ Mitscherlich, Medicine , p. 129. See also Nuremberg Document NO-1186.

- ↑ Mitscherlich, Medicine , p. 130. There the statement that SS-Standartenführer Calling wrote the letter. Ernst Lolling is named as the author of the Nuremberg Trials Project ( Memento of March 4, 2016 in the Internet Archive ). The letter in the facsimile at the Nuremberg Trials Project ( Memento from July 11, 2012 in the web archive archive.today ) (Nuremberg document NO-1188)

- ↑ Mitscherlich, Medicine , p. 130 f. with reference to the Buchenwald diary, p. 23 (Nuremberg Document NO-265)

- ↑ Klee, Auschwitz , p. 130. Schröder's affidavit of October 25, 1946 at the Nuremberg Trials Project ( Memento of August 2, 2012 in the web archive archive.today ) (Nuremberg document NO-449)

- ^ Letter from Eugen Hagen to Gerhard Rose dated October 4, 1943 (Nuremberg Document NO-2874), see Mitscherlich, Medicine , p. 158 f.

- ↑ Mitscherlich, Medizin , p. 160 ff. Haagens letter to the Nuremberg Trials Project ( Memento from July 14, 2012 in the web archive archive.today ) (Nuremberg document NO-1059). Further information in a letter from Haagen to August Hirt of November 15, 1943, see Nuremberg Trials Project ( Memento of July 11, 2012 in the web archive archive.today ) (Nuremberg Document NO-121)

- ↑ Mitscherlich, Medicine , p. 162. The letter from the Nuremberg Trials Project ( memento from July 20, 2012 in the web archive archive.today ) (Nuremberg document NO-122)

- ↑ Klee, Auschwitz , pp. 130ff.

- ↑ Klee, Auschwitz , pp. 132, 212.

- ↑ This assumption in Klee, Auschwitz , p. 133.

- ↑ Udo Benzenhöfer: Nürnberger Ärzteprozess: The selection of the accused. Deutsches Ärzteblatt 1996; 93: A-2929–2931 (Issue 45) (PDF, 258KB)

- ↑ Benzenhöfer, Ärzteprozess , page A-2930 Ibid. A scheme related to the trial on the position of the accused in the German health system.

- ↑ Ebbinghaus, Blick , p. 60.

- ↑ This assessment by Ulf Schmidt: Justice at Nuremberg. Leo Alexander and the Nazi Doctors' Trial. palgrave macmillan, Houndmills 2004, ISBN 0-333-92147-X , p. 226

- ↑ Excerpts from Rose's statements in: Mitscherlich, Medicine , pp. 120–124, 131–132, 134–147. See also Schmidt, Justice , p. 226 ff.

- ↑ Minutes of the negotiation , p. 6231 ff., Quoted from Mitscherlich, Medicine , p. 120.

- ↑ Minutes of the negotiation , p. 1197, quoted from Mitscherlich, Medicine , p. 153.

- ↑ Minutes of the negotiation , p. 6568, quoted from Mitscherlich, Medicine , p. 132.

- ↑ Justification of the judgment , p. 194ff., Quoted from Mitscherlich, Medicine , p. 133.

- ^ "Guidance in the institution" form , November 9, 1953, in: Dörner, Ärzteprozess , pp. 8/03125 f.

- ^ See Dörner, Ärzteprozess , pp. 8/03094 ff. Ernst Georg Nauck had previously contributed four declarations on oath instead of Rose's defense. The declaration in English translation at the Nuremberg Trials Project ( Memento from March 4, 2016 in the Internet Archive ). On the efforts to get Rose's release see also: Angelika Ebbinghaus: Views on the Nuremberg Doctors Trial. In: Dörner, Ärzteprozess , (indexing volume), p. 66.

- ^ Petition on the occasion of the meeting of the Free Association of German Hygienists and Microbiologists in Hamburg on September 29, 1950. In: Dörner, Ärzteprozess , p. 8/03104.

- ^ Die Zeit, March 18, 1954.

- ↑ a b Ebbinghaus, Blick , p. 66.

- ↑ This assessment by Robert Sigel: Requests for Grace and Releases. War criminals in the American zone of occupation. In: Dachauer Hefte 10 (1994), ISSN 0257-9472 , pp. 214-224, here pp. 221 f.

- ↑ Gerhard Rose: To my acquaintances, friends and relatives who thought about my family and myself during the years of my captivity. Flyer from July 1955. In: Dörner, Ärzteprozess , p. 8/03146.

- ^ Judgment of the Federal Disciplinary Chamber VII of October 24, 1960 (Az. VII VI 8/60). In: Dörner, Ärzteprozess , pp. 8 / 03173-8 / 03205.

- ^ Judgment of the Federal Disciplinary Chamber VII of October 24, 1960 (Az. VII VI 8/60). In: Dörner, Ärzteprozess , S. 8/03204.

- ^ Judgment of the Federal Disciplinary Chamber VII of October 24, 1960 (Az. VII VI 8/60). In: Dörner, Ärzteprozess , p. 8/03199. On Wohlrab see Ernst Klee: Das Personenlexikon zum Third Reich. Who was what before and after 1945. Fischer Taschenbuch, Frankfurt am Main 2005, ISBN 3-596-16048-0 , p. 684 and Mitscherlich, Medicine , p. 146. For Nauck see Klee, Personenlexikon , p. 428, and Klee , Auschwitz , p. 311.

- ↑ a b c Interview by the chairman of the Federal Disciplinary Chamber 7 in Hamburg on October 21, 1960. (Mitscherlich's memo ) in: Dörner, Ärzteprozess , p. 8/03162 f.

- ^ Letter from Alexander Mitscherlich to Erich Rosenthal-Pelldram from October 29, 1960. In: Dörner, Ärzteprozess , pp. 8/03165 ff.

- ↑ a b Judgment of the Federal Disciplinary Chamber X of October 3, 1963 (Az. X VL 13/62). In: Dörner, Ärzteprozess , pp. 8/03206 ff.

- ↑ Mitscherlich, Medicine , p. 118 f. See also: Letter from Eugen Kogon to Alexander Mitscherlich of December 9, 1960. In: Dörner, Ärzteprozess , pp. 8/03170 f.

- ↑ Mitscherlich, Medizin, p. 126. The diary in the facsimile at the Nuremberg Trials Project ( Memento from July 15, 2012 in the web archive archive.today ) (Nuremberg document NO-265).

- ↑ Dietzsch's statement of April 3, 1947 at the Nuremberg Trials Project ( Memento of July 11, 2012 in the web archive archive.today )

- ↑ On Dietzsch's person, see Dörner, Ärzteprozess , p. 88.

- ↑ List of defendants in the Buchenwald trial at jewishvirtuallibrary.org . See also: Letter from Eugen Kogon to Alexander Mitscherlich of December 9, 1960. In: Dörner, Ärzteprozess , pp. 8/03170 f.

- ^ Letter from Gerhard Rose to Rudolf Augstein . Undated, probably May 1989. In: Dörner: Ärzteprozess , pp. 8/03231 f.

- ^ Judgment of the Federal Disciplinary Chamber VII of October 24, 1960 (Az. VII VI 8/60). In: Dörner, Ärzteprozess , p. 8/03191.

- ↑ Cf. Bernd Ziesemer, A private against Hitler: In search of my father. Hamburg 2012, p. 17. ISBN 9783455502541

- ↑ Klee, Auschwitz , p. 132.

- ↑ At Rose's funeral, instead of flowers, donations were requested for Stille Hilfe or the Max Planck Society. See Klee, Auschwitz , p. 133.

- ↑ Award certificate in: Dörner, Ärzteprozess , p. 8/03228.

- ↑ Hellmann: Gerhard Rose 80. In: Deutsches Ärzteblatt 4/1977, p. 261.

- ↑ Hanno Kühnert: A FAZ letter to the editor caused trouble. Why a lawyer got upset about a professor's statement. In: Frankfurter Rundschau , December 17, 1981.

- ^ Letter from Gerhard Rose to Rudolf Augstein . Undated, probably May 1989. In: Dörner: Ärzteprozess , pp. 8/03231 f. Rose referred to: Jörgen Pötschke: Result equal to zero . In: Der Spiegel . No. 34 , 1978, p. 168 ( online ).

- ^ Media information from Mut-Verlag Assendorf , signed by Alfred Schickel , in: Dörner, Ärzteprozess , p. 8/03234

- ↑ Mitscherlich, Medicine , p. 15 f.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Rose, Gerhard |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Rose, Gerhard August Heinrich |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | German tropical medicine specialist, head of the department for tropical medicine at the Robert Koch Institute, sentenced to life imprisonment in the Nuremberg doctors trial |

| DATE OF BIRTH | November 30, 1896 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Danzig |

| DATE OF DEATH | January 13, 1992 |

| Place of death | Obernkirchen |