History of Norway from Harald Hårfagre to the unification of the empire

swell

The most important written sources about the various events of this period are saga literature from the 12th and 13th centuries. Above all, the royal sagas should be mentioned here. How far they reproduce older oral traditions is the subject of saga criticism and highly controversial. The oldest news about the beginning of the Norwegian Empire is the little saga Ágrip , which was written at the end of the 12th century. Some smaller Latin royal sagas, the anonymous Historia Norvegiae and the Historia de antiquitate regum Norvagiensium by Theodoricus Monachus, date from the same period . These are short overviews, the main purpose of which is to show the royal ancestry and also to organize the chronology. The Icelanders Sæmundur fróði (1056–1133) and Ari fróði (1067–1148) were the pioneers in this field. The more extensive sagas came later: the anonymous Fagrskinna and the somewhat younger Heimskringla Snorris . The Morkinskinna is a bit older . When Snorri wrote, 300 years had passed since Harald. However, the great sagas contain many skald poems from Harald's time. They are cited in the sagas as evidence of the portrayal. Some of the skald stanzas are undoubtedly real and contemporary, others are later embellishments. Ottar reports on Norway as a country in his report on his expedition on behalf of King Alfred the Great of England.

In addition, there are also some foreign publications with sporadic news about the Norwegian situation.

The events

Between 800 and 850 a number of large ship graves were built in Avaldsnes (North Karmøy ). They testify to a new center of power after rivalries, especially with the chief of Ferkingstad (South Karmøy), which arose here towards the end of the 8th century. In the end, a chief with headquarters in Åkra (West Karmøy, today Åkrehamn) apparently prevailed. The unrest that led to the dissolution of the small western Norwegian kingdom of Bøvågen (on the coast of Karmøysund) evidently took advantage of Harald Hårfagre during his conquest. It is largely believed that he came from the outside as a conqueror, but there is debate about where he came from and what his background was. Even the Kings sagas do not agree on this. At the end of his life he is referred to as the King of Westland with his estates in Rogaland and Hordaland . The saga literature reports that he had connections to Sogn , the father was the king of Oppland Halvdan Svarte and the mother Ragnhild , the daughter of Harald Gullskegg in Sogn. He is said to have grown up with his maternal grandfather, and the starting point of his ventures is said to have been Sogn. There is also the opinion that the descent from Halvdan Svarte is a late construction from the 13th century, which should prove a root in the area around the Oslofjord in order to be able to reject the claims of the Danes in this area. It is also believed that he came from the powerful Karmøy family who had their seat in Avaldsnes on Karmøy. Harald ousted the previous ruler on Avaldsnes and took over his power base. His empire was a coastal empire with bases as far as Kristiansand and Arendal . His power base was initially the crown estates, which he took over from the subjugated chiefs and their headquarters, later taxes and fines were added. The resulting income enabled him to build a military strength that allowed him to control most of the trade on the south west coast. In the dispute with the small kings of the area about the takeover of Halvdan's kingdom, he prevailed and defeated them. When he had secured the loyalty of the big farmers and rulers of the area, he pushed further north and attacked Trøndelag.

The term “king” for the rulers of this time is not without controversy, because it is usually associated with a ruling organization that should not have existed at that time.

The time of Harald Hårfagre

Around the year 900 Harald Hårfagre, the first Norwegian king, united several tribal areas into one empire. But what is generally described today about the size and structure of his empire is likely to be Snorri's construction. Apart from that, the term Norway then only included the coastal area, namely norðmanna land , as the Ottars report shows. Sami lived after him north of Lofoten and in the highlands of Central Norway . According to Snorri, he conquered Trøndelag starting from the east and then in turn subjugated all rulers on the coast to the south as far as the Stavangerfjord and established a new administration by setting up dependent Jarle everywhere. This construction by Snorri almost certainly has little to do with reality. The jars of the eastern part of the country are more likely to have been tied to the Danish king, the other chiefs not appointed by him, but merely to have become somewhat dependent. However, it can be considered certain that he had a power base in the southern western part of the country. He is also likely to have exercised supremacy over other parts of the country, the content of which, however, can only be vaguely determined. Charges, meals during visits and military successes in the war should represent the main content. The king did not rule over an area, but over people. Torbjørn Hornklove calls him dróttin norðmanna (King of the Northmen). In return for the taxes, he was responsible for the external defense of his sphere of influence. This led to the great campaign to the west to the Scottish islands, from where Vikings had repeatedly made raids to Norway. There he made Sigurður, the brother of his friend Røgnvald, to jarl over the Orkneys . Ari Froði probably determined the year of his death 932 on a reliable basis. All other figures have been reconstructed: The sagas report that he died at the age of 80 and was ten years old when his father died, and that ten years later he completed the unification of the empire. So one arrives at the battle of the Hafrsfjord in the year 872. The round numbers of the saga writers rather indicate an estimated time. Today the battle starts much later. The fact that this battle was the final point is due to the fact that the other battles are only generally reported, but Haraldkvæði des Torbjørn Hornklove describes this battle in the greatest detail. There is no reliable indication of which stage this battle formed in the process of conquest. This song also contradicts the later description that Harald led a conquest battle there to unify the empire. Rather, he was already master of the south-west country afterwards, and it was an attack from the neighboring region, which he successfully repelled. The wave of emigration to Iceland is therefore not due to him, but to conflicts with the Landnámabók in the domain of the Ladejarls on the Trondheimfjord Håkon Grjotgarðson.

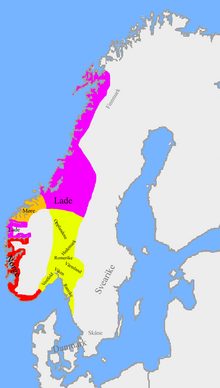

A number of historians start the "Norrøne Period" with this battle, which according to them ends on May 8, 1319 with the death of the last Norwegian king of the Sverre family, Håkon Magnusson. After this battle, Norway can be roughly divided into three domains: Østlandet, which was under Danish rule, Vestlandet under the Harfagre family, and Trøndelag and Northern Norway under the Ladejarlen .

Harald died at home in old age, the empire was not at peace. Already during his lifetime there was fierce fighting between the Jarlen. Harald's sons did not keep peace among themselves either. In particular, Erik Blodøks was after his brothers, which is why he got his nickname (blood ax). According to the skalds, this is due to the fact that all of Harald's sons had the same right of inheritance and that his attempt to transfer the kingdom to one, Erik Blodøks, failed. Harald had already made him co-regent, but the other sons did not accept his upper kingship. Equal rights for all royal sons in the line of succession was also common on the continent, as was the attempt by the ruling kings to appoint only the eldest son to the line of succession.

The time of Erik Blodøks and Håkon the Good

Erik Blodøks took over the royal rule after Harald's death in 932. The contemporary skald songs refer to him as the King of Vestland. His rule does not seem to have extended further. He adopted his father's style of government and built his rule on military might. The resulting high tax burden led to conflicts among the population. After two years his younger brother Håkon appeared from England, so that he had to flee. It got its name because, according to the saga literature, he killed many of his brothers. He fled to the English Danelag , where he was slain in the battle for the city of York. His sons found acceptance and support from the Danish king Harald Blåtand , from where they tried to regain the rule.

Håkon (920–961), who was later called the Good , took over the rule. It did not apply to the whole of Norway either, but was restricted to the west and the area north of it. His strongest support was Sigurd Ladejarl in Trøndelag. He brought a different concept of government with him from the court of Æthelstan , where he grew up. He gave the peasants back the goods they had confiscated from Harald and Erik and thus bought himself inner peace. His enemies were the sons of Erik and later King Harald Blåtand of Denmark. The other peasants also saw in them enemies, so that the interests of the king could be combined with their interests. The peace within and the threat from the sea led to a new defense order, called Leidangen , which means the presence of ships. This new order included that the people themselves built ships for defense, equipped and then deployed to the army. The country was divided into certain districts, whose residents had to provide a certain type of ship. The king had the right to request the draft. Håkon changed the expensive standing army into a peasant army that had to be mobilized on a case by case basis and introduced conscription. However, he had to accept that a peasant army was not as strong as a professional army. The terminology also changes: The skalds no longer speak of hirðmenn (= follower), but of þegnar (= free peasants as subjects). The new system also led to a different responsibility structure: while the peasants previously only felt responsible for the defense of their own farm, conscription led to an awareness that they had to defend the entire royal territory.

This new defense order initially only applied to Vestland and only gradually gained structure. But the residents of Trøndelag are also likely to have quickly joined this order.

Another change occurred in the legal system.

While Harald with his military power essentially only safeguarded his own power and defense interests, Håkon sought more balance with the peasants and thus came into the role of referee. This led to the fact that he was given a leading role in the thing assemblies and also in the judiciary. There were two large thing districts in his realm: Gulathing for Vestland and Frostathing for Trøndelag. Over time, i.e. in the 11th century and afterwards, other areas joined. The Frostathing was older, but remained very limited in space. In contrast, the gulathing was much larger in terms of space and population. In the middle of the 10th century, in the time of Håkon, the thing system was reformed: a direct popular assembly of all free men became a delegate thing. The saga literature attributes the development of the thing being to Håkon, and this is also plausible, since the thing reform began in his narrower domain.

Norwegian Jarle under Danish suzerainty

After the death of Håkon the Good, the sons of Erik gained the upper hand. But first, Harald Blåtand moved to Tønsberg and received homage there as king around 960. With this he secured his kingship in the Oslofjord and at the same time acquired his upper kingship over the rest of Norway, which was also passed on to his descendants. It was important to him to have his back free in the dispute with the German Kaiser. He set Erik's sons Harald Gråfell and his brothers as sub-kings over the various parts of the country. His own presence in Norway is likely to have been sporadic. The Erik sons exercised the actual rule in the country. 962 attacked Harald Gråfell and his brother Erling Sigurd Ladejarl in Aglo in Stjørdal / Trøndelag , who had been Håkon's support, and burned him in his house. This incident led to long-term hostility between the Ladejarlen and the Harald Hårfagres family. With this, Trøndelag came under their rule with the donations of the Sami. They resumed Harald Hårfagre's ruthless policies and eliminated all independent rulers. Perhaps they no longer counted on enemies from outside against whom they would need internal support. But apparently they were becoming too high-handed; because Harald Blåtand fell out with them and allied himself with their worst enemy, Håkon Sigurdsson, the son of the slain Sigurd Ladejarl, who had been abroad since the death of his father. This became Harald's vassal and received from him Trøndelag as Jarl. Harald Gråfell was killed in an ambush around 970 on the Limfjord (Jylland), where Harald had ordered him to reconcile. Håkon Jarl then moved to Denmark with a large force to support Harald Blåtand in 974 in the fight against the German Emperor Otto II.

Erik's sons were Christians, but Håkon Jarl was not. Harald Blåtand had also become a Christian around 960 and boasted that he had Christianized Denmark. He also tried to Christianize Norway and forced Håkon Jarl to take missionaries with him. Harald combined conquering and missionary activity. On departure, however, Håkon set them ashore elsewhere on the coast and drove back without them. In addition to the anti-Christian attitude, a certain striving for independence on the part of Håkon also seems to have played a role. This open resistance led to a break with the king. This drove to Norway with a fleet. Håkon ordered the mobilization of the Norwegian fleet, just as Håkon the Good had organized, and was able to repel the attack in the battle of Hjørungavåg . Where and when the battle took place is not certain. The sagas report that Svend Tveskæg was already king at this time . Saxo Grammaticus claims that the battle already took place in the time of Harald Blåtand. But historical research puts the battle on the year 986, when Svend Tveskæg was already king. The later poetry enriched the event very much, in particular the news that on the Danish side the Jomswikings fought with 120 ships and on the Norwegian side even 360 ships. The very old little sagas from the 12th century (Historiae Norvegiae, Ágrip) do not know the battle at all. But it should be certain that a fight has taken place and that Håkon Jarl has succeeded in shaking off Danish supremacy over the west coast of Norway. But he did not become king. He was reportedly unpopular because of his tyrannical nature. His reign ended abruptly through treason. A servant killed him in the pigsty in the yard of one of his wives. The conflict with the king must still have existed, because his son Erik Håkonsson fled before Olav I. Tryggvason , who was advancing from the west, not to Denmark, but to Sweden. According to the Icelandic sources, which are usually based on English sources, this happened in the year 995. However, that did not prevent Erik from marrying the daughter Svend Tveskægs Gyda.

He was succeeded in 995 by Olav Tryggvason. His rule only interrupted Danish sovereignty for five years. The Christianization of the western Norwegian coast is ascribed to him. This is interpreted as a measure to counter the threatened expansion of rule by the Danish king through the Danish proselytizing there. Missionary work was a national matter for him. He interfered in the power struggle between the Wendish Duke Boleslav and the Danish King Svend Tveskæg, drove with a fleet to the Baltic Sea and was killed in the battle of Svolder against a united Swedish-Danish fleet in 1000. It is not known where Svolder is. Longships were used on a larger scale under him, which is interpreted as a symbol of national self-confidence.

The Danish King Svend Tveskæg took over his rule as King of Norway. He used as Jarl Erik Håkonarson, the son of Håkon Jarls in Vestland and Trøndelag. In the east, petty kings still seem to have ruled as vassals. King Olof Skötkonung of Sweden probably got Møre og Romsdal and Romerike as tribute land and appointed Sveinn, also a son of Håkon Jarl, as Jarl.

The time until the unification of the empire (1066)

Olav the saint

Olav, the saint , came to Norway around 1015 from England, where he had participated in Viking battles, in all probability with the agreement of Canute the Great , to rule there. After the victorious battle of Nesjar in the Oslofjord in the spring of 1016 against his only serious adversary Sven, Uncle Håkons, he was generally recognized as king. However, he had constant resistance from the aristocrats of Trøndelags. In 1024 he held a meeting with Bishop Grimkjell from England in Mostar, where he created the basic principles of the future Norwegian church constitution. The overthrow of the opponents and the subsequent expropriation of their property led to enmity in Trøndelag that would later lead to its downfall. In 1026 he fought in the Battle of Helgeå together with Ånund of Sweden against Knut. Although he caused great damage to Knut, he still had enough ships to drive him away. When he killed the second most powerful man in Norway, Erling Skjalgsson , who was also Knut's son-in-law, in the Battle of Boknfjord on December 21, 1027 , Knut moved from England with a large fleet against him to Norway. The number of 600 ships is incredible, as is the fact that the king's ship was a 60-seater . Almost all previous allies had now distanced themselves from Olav. Knut still traditionally felt himself to be the Upper King of Norway, but Olav had refused to submit to him. Olav fled to Novgorod. Knut was honored as king in Norway and installed his nephew Håkon as Jarl over Norway before he returned to England. Håkon was killed on the return journey at sea after visiting Knut in England. Thereupon Olav tried to use the power vacuum in Norway in 1030 and returned to Norway with 400 men of the Swedish king Anund Jakob , who was his brother-in-law. Thereupon the big farmers, especially from Trøndelag, gathered a large army, and on July 29, 1030 the battle of Stiklestad broke out, during which Olav was killed.

The fact that the son of Olav Magnus was baptized (according to the saga of the skald Sigvat , because the son was born in the night and was so weak that it was not believed he would live, but the royal father was never woken up allowed), throws a clear light on the ideals in the immediate vicinity of the king, because the name is expressly referred to Karolus Magnus. In his time Karl the Gr. regarded in Norway as the founder of the new kingship in Central Europe. Its kingship was Christian and was based on a specific idea. Even Isidor had at the beginning of the 7th century in his Etymologiae wrote: "lively a recte agendo vocati sund" ( "The Kings are so called because they act righteously have"). Part of this idea was that the king was in the tradition of the Old Testament King David and derived his rule from God. For Norway this meant that a king who wanted to assert himself on an equal footing with the other kings had to be Christian. Without this program of Olav, a whole kingdom of "Norway" could not be achieved. Such a program and such an ideology was not developed in his predecessors, which is why the actual unification of the empire is started with him and not with Harald Hårfagre, who had only extended his power to other areas, like many others before and after him.

Immediately after Olav's death, Knut installed his son Sven as Jarl in Norway. His English mother Alfiva ( Ælfgifu in English sources ), Knut's first wife, also came to Norway with many Danes. She had a great influence on his decisions. In Norway the most powerful peasant leaders, who had joined Knut against Olav, had expected the dignity of Jarl for themselves. Knut's decision for Sven and his tyrannical style of government brought about a radical change in mood against Knut and his son. Alfiva had apparently enforced laws based on the English model through her son, which the Norwegian aristocracy felt as presumptuous and contrary to tradition. After all, they were called Alfiva Laws . They are only preserved in quotations from other texts. The rapid change in mood was accompanied by the church with the creation of legends about Olav as a saint. Snorri later stylized Olav as the national king who turned against the foreign Danes. In addition, Bishop Grimkjell, who came from England, knew about the political and dynastic importance of a holy king and did his best to promote the creation of legends. However, one should not overestimate the importance of the church in politics. The bishops came from abroad and had no connection with the ruling upper class. Neither in the sagas nor in contemporary skaldic poetry are therefore assigned a special role. They had to fit into the existing power structure. Therefore it must have been the powerful chiefs Kalv Arnesson and Einar Tambarskjelve who stood behind the elevation of Olav to saint. As early as 1040, i.e. 10 years later, the Olavsmesse was reported. The translation to the high altar of the Klemenskirche in Nidaros probably took place around 1036, i.e. only after Knut's death in 1035. At that time, Sven and Alfiva left Norway.

Magnus the good

Magnus the Good ruled in Norway from 1035 to 1046, also in Denmark from 1042 to 1046 and exclusively in Denmark from 1045 to 1046.

Initially, the North Sea region of Knuts was factually divided among his sons, although Hardeknut was supposed to be the only legitimate son to succeed him. Five years later, one of the two, Hardeknut , became king over Denmark and England, after apparently killing his brother Harald Hasenfuß there and probably also killing him. His other brother Sven had been expelled from Norway and was probably staying with his mother Alfiva in England. Two years later, in 1042, Hardeknut also died. The Danish-English royal rule dissolved. In England, Edward the Confessor became king. There was no heir to the throne in Denmark. Magnus filled this vacuum.

In 1041/1042 Magnus moved with an army to Denmark when Hardeknut was still alive but was bound in England. So when Hardeknut died in England, Magnus was already in Denmark and was accepted as king over Denmark. At the same time, Sven Estridsson , a nephew of Hardeknut, joined Magnus and became his Jarl. But very soon Sven was also honored as king in Denmark. There were armed conflicts between Sven and Magnus, all of which Magnus won. Because of these arguments, Magnus was more in Denmark than in Norway during these years. There were also attacks by the Wends on southern Denmark, which he had to fend off as the Danish king, which also happened in 1043 in a battle near the city of Schleswig.

In 1045 Harald Sigurdsson , later called Hardråde , returned from Byzantium, laden with gold, where he had been in imperial service. This led to a conflict between the half-brothers, which became dangerous for Magnus because Harald allied himself with Sven Estridsson and the Swedish King Anund Jakob. A comparison was made that included a dual kingship, in which Magnus should have his focus in Denmark, but Harald his own in Norway. This did not end the conflict, but the imminent death of King Magnus in 1046 prevented further conflicts.

Harald Hardråde

Harald Hardåde was King of Norway from 1047 to 1066. He is portrayed in the sagas as the counterpart to Magnus the Good and represents the tough military line of tradition of Norwegian royalty. He was a warrior and engaged in constant fighting. On the one hand, he went to the field against Sven Estridsson of Denmark, less to conquer it than to gain booty to support his army. It was not until 1064 that he promised in an agreement with Sven that he would refrain from looting trains in the future. Then he tried to conquer the crown of England, to which he laid claim as successor to Canute the Great. He was killed on September 25, 1066 in the Battle of Stamford against Harald Godvinson himself.

Domestically, he was rightly called hardråde . Having passed through the Byzantine school, a Caesaropapist element came into his style of government with all the military consequences. He arbitrarily appointed unconsecrated bishops and came into conflict with the Pope. He regarded the Olav Church in Nidaros as the king's own church and took the offerings for St. Olav in order to reward his entourage. When the Archbishop Adam v. Bremen then sent a protest delegation to the royal court, it was dealt with with the telling remark that he knew no other archbishop than the king himself. The one from his predecessor Magnus in consultation with Adam v. Bishop Bernhard, who had brought with him to Bremen, therefore left the country and waited for Harald to die in Iceland. When the peasants of his home country in Oppland insisted on privileges which Olav the Saint had granted them, which related to services to the king and self-government, he covered them with war, burned everything down and expropriated much of the land from his adversaries. Throughout the country he proceeded equally brutally against any resistance, so that the skalds finally adopted his Byzantine nickname "Bulgarian burner" for him.

With Harald Hardråde, the unification of the empire was complete. While the genealogical sequence of kings was sometimes doubtful up to him, the time began with him when the descent of kings can be considered certain.

Olav Kyrre

According to Harald Hardråde, his two sons Magnus II and Olav Kyrre initially had a double kingship . Practically nothing is known of Magnus apart from the year of his death in 1069. He donated St. Patrick's Isle near the Isle of Man to the Church. From 1069, Olav was the sole ruler in Norway. He didn't wage wars. In 1068 he renewed his father's peace treaty with Sven Estridsson from 1064. In contrast to the contemporary Danish king, he had no interest in regaining England. Sven Estridsson also failed to carry out a plan to undertake a military campaign to England that had been considered in the 1980s. The interest of the Norwegians was directed more towards Scotland, Ireland and the islands north and west of Scotland.

He knew Latin and enjoyed books and lived on an estate in Båhuslän until his death in 1093 .

A number of profound changes in the internal administration of the state and the church are ascribed to him, some of which, however, probably only took place at the beginning of the 12th century. This also applies to the founding of Bergen, attributed to him, for which the earliest archaeological evidence only became visible for 1130.

Magnus Barfot

Magnus III. Barfot took over the rule after his father in 1093. He is again portrayed as the opposite of his father, as a warrior, like his grandfather Harald Hardråde. At the thing meetings in Trøndelag and Oppland, his cousin Håkon Magnusson Toresfostre, son of Magnus Haraldsson , was proclaimed king. He was the foster son of the powerful chief Steigar-Tore, who apparently urged him to claim the kingship. Magnus never recognized him as a co-regent. There was no coronation. In 1093 there was probably a fight between him and Magnus. Håkon fell ill on a ptarmigan hunt and died in 1094. Magnus later hung the foster father Steigar gates because of this local uprising. Håkon Magnusson is therefore not counted as a king. Under no circumstances was he king of Norway, but at most he was the pretender to the throne in the Trøndelag and Oppland area.

In 1098/1099 King Magnus made the first campaign to the islands around Scotland and subjugated the Orkneys, where the two Jarle Páll and Erlendur were at odds with each other, and sent his son Sigurd to rule the Orkneys. Likewise, he brought the Faroe Islands, the Isle of Man and many other islands under his suzerainty and made the Scottish king recognize that the islands west of Scotland were under Norwegian rule.

In 1101 he made a peace with King Inge of Sweden and King Erik of Denmark in what is now Kungälv , on which occasion he married the daughter of the Swedish king Margarethe Fredkulla. 1102/1103 he undertook a second campaign to these islands. On that occasion he was ambushed in Ireland and killed.

Magnus left four children: the sons Sigurd Barfot (Jorsalfari), Olof Barfot, Eystein Barfot, whose mothers are unknown, and his wife Margarethe's daughter Ragnhild Barfot (Magnusdotter).

The inner development in the Viking Age

In the period from Harald Hårfagre to Magnus Berrføtt , Norwegian kingship underwent a profound change. While Harald's rule was still more or less limited to the coastal area and consisted of a tax obligation, in the end the rule had expanded to the eastern inland and brought about a substantial centralization of rule on the king, with the suppression of local rulership structures like them was constitutive for an empire in the medieval sense. Three factors were decisive for this: on the one hand, the church had a large share in the internal structure of the empire, on the other hand, and was significantly promoted by it, the dynastic element in the kingship had brought about a systematic expansion of the king's position, and thirdly, the expansion of the internal power apparatus in the Systematically continued over time. Because of the inheritance of the royal title, the son could continue where the father had left off. This claim of a family to the title of king was justified primarily with sacral legitimacy, whereby the Germanic idea of the salvation of the king was also taken up. So it was not so much the conquests of parts of the country by the early kings than the new ideas about kingship penetrating from the mainland that had a decisive influence on the development. Their realization also led to equality with the other European Christian empires. The local petty kings disappeared. The circle of European rulers with whom Norway dealt essentially consisted of the Scottish and English kings, the kings of Sweden and Denmark, the Duke of Saxony and the Grand Dukes of Kiev and Novgorod . These were intertwined by mutual marriages.

The Norwegian kings have now managed to participate in these marriage alliances: Harald Hardråde married Ellisiv, the daughter of Grand Duke Jaroslaw of Novgorod. Her daughter Ingegjerd first married the Danish King Oluf I. Hunger , the third son of Sven Estridsson , then the Swedish King Philipp Hallstensson . Olav Kyrre von Nidaros (later Trondheim) married Ingrid, a daughter of Sven Estridsson. Magnus Barføt married Margareta (fredkolla), daughter of the Swedish King Inge Stenkilsson. Previously, the marriage to Mathilda, the sister of the Scottish king was planned. His son Sigurd Jórsalafari married Malmfred, the daughter of the Grand Duke of Kiev Mstislav . His sister married Harald Kesja, the illegitimate son of the Danish King Erik Ejegod . All of these marriages were political marriages that had to secure contracts and cooperation agreements. The peace agreement between Olav Kyrre and Sven Estridsson was strengthened by the fact that Olav Sven's daughter and Sven's son married Olav's sister. Margaretha, who married Magnus Berrføtt, was nicknamed friðkolla , (= peace girl ) because she had sealed the peace between Magnus and Inge. In addition, there were many reciprocal educational and employment relationships. Harald Hardråde had a son raised by King Adalstein. After the death of Magnus the Good , his brother Tore went into the service of the Dane Sven Estridsson and achieved a high position with him. Finn Andresson also went to Denmark, although he was married to his niece Harald Hardrådes and was the uncle of his Norwegian wife. In Denmark he became Jarl von Halland under Sven Estridsson and went with him in 1062 to the battle of Niså against Harald. However, the stabilizing effect was limited and actually did not extend beyond the period of rule of the people involved.

Initially, the rulers of Denmark and Norway felt that this was actually a kingdom. Magnus the Good and Harald Hardråde also felt they were entitled to rule over Denmark, and Sven Estridsen also thought, after Adam von Bremen, that he was actually Harald Hardrådes Oberkönig and Harald his Jarl. But gradually the kings of both countries became aware that they were only kings in their own country, and a national kingship developed. But the awareness that it was actually a unified overall kingdom only disappeared in the 13th century. In the sixties of the twelfth century, the Danish king Waldemar tried to revive this idea, and his son Waldemar Seier tried the same at the beginning of the thirteenth century. The Swedish kings, on the other hand, directed their policy towards two states. Anund Jakob allied themselves with Olav the Holy against Canute the Great . Later he helped Magnus the Good against Sven Alfivason . When Olav had also subjugated Denmark, he supported Harald Hardråde as a possible anti-king. Harald lost this support when he succeeded Magnus and also ruled over Denmark. Instead, Anund now supported Sven Estridsson . So the policy of Sweden was always to prevent a connection between Norway and Denmark.

Violence was also a major factor in the unification of the empire. The king's suppression of peasant society, as carried out by Harald Hardråde, eliminated any centers of power besides the king. Nonetheless, as a rule, peaceful cooperation between the king and the peasant population was sought. Key figures were the members of the rural land nobility who were seated throughout the country and were called "Lendmenn", which was sometimes wrongly interpreted as a feudal man . Its original position can be roughly determined from the earliest Norwegian laws. The Lendmann had a position between the landowning peasants and the Jarl. Although the loinmen were given many important duties by the king, the sagas never mention the loinmen in connection with administrative duties. There they appear only as political allies of the king. In the twelfth century there were about 80 to 100 loinmen in the country, in the thirteenth century there were considerably fewer. Among Magnus Berrføtt and his sons only 35 are mentioned. But when someone became too powerful, like Einar Tambarskjelve, who was almost as powerful as a Jarl before, Harald Hardråde got him out of the way. The relationship between Lendmenn and the king was feudal: the Lendmann pledged allegiance to the king, and the king gave him part of the income from the crown property. But the land that gave the Lendmenn social status and made him a valuable ally of the king was his personal property. Later it was also added that loyal followers of the king were provided with confiscated goods by him, even if they were not of high origin. This applies in particular to the area in the Oslofjord, where studies of the distribution of the land holdings revealed that large parts later passed into the possession of the bishop and others into the later powerful Sudrheim family. Both are attributed to Harald Hardråde's confiscations. The powerful families of the country were interwoven through mutual marriages to form a nationwide network in which the king was also integrated. It was a real aristocracy and not just a nobility, albeit in close cooperation under the power of the king. The campaign was an essential link and the looting an essential goal. According to Snorri, one of the main drivers behind Harald Jarsalfares' march was that reports from the Norwegian participants in the first crusade under Norman rule came into the country about the fabulous wealth that was to be won there, and the loins therefore pushed him.

The royal team, the hirðmenn , also played an important role in the unification of the empire . In contrast to the mobilizable peasant militia, it was a permanent institution that belonged to the king's court and had to implement his will. In the twelfth and thirteenth centuries they are an imperial institution. During the travel royalty period , the king moved from one country estate to another. The sagas therefore report that the number of hirðmenn among the district aristocrats was limited because of the necessary food. Olav the saint was allowed to take 120 hirðmenn , Olav Kyrre 240 ; that Harald Hardråde would have put up with a limitation seems unlikely. The king had a monopoly on this institution. However, it is known that the archbishop also carried such a force with him. But in the eleventh century one can clearly see the king's vigorous action against any attempt to entertain a force that might threaten him.

Another factor in the unification of the empire were the thing assemblies . Nothing is known about the involvement of the king in the thing in the early days. But the Christian kings were strongly committed to legal peace, thereby strengthening their authority and power at the same time. Magnus the Good was represented on the thing by proxy. Only with the laws at the end of the twelfth century does the situation become clearer. Because there criminal acts against property and life were also understood as directed against the king, so that in addition to the satisfaction of the injured he received his own fine, a not insignificant source of income. Concern about the administration of justice strengthened the royal central power. Because the royal proxy also enforced satisfaction for the opponent when enforcing the royal fine, the central royal authority gradually took over enforcement in general.

Everywhere in the country there were royal agents ( yfirsókn ) who represented the king on the thing or in other matters. Their task was not only in law enforcement and other police tasks, but also in the control of the equipment and armament of the ships and crews, as well as in monitoring the warning system against enemies on the coast. The authorized representatives were divided into lendmenn and ármenn . The former were the agents from the landed nobility, the others were other servants. The gulathingslov makes no difference between the two. But the Frostathingslov says that the loin man has a much higher social status and a closer connection to the king.

It can be assumed that the main impetus for the idea of kings came from England. The English system of sheriffs is similar to that of the royal agents in the country. The Norwegian Church was founded by English priests on the English model. Several Norwegian kings were able to fall back on the experiences of a longer stay in England, such as Håkon the Good , Olav Tryggvason and Olav the Saint . In the eleventh century there were influential English counselors at the royal court. Bishop Grimkjell played an important role in building the Church under Magnus the Good. The Englishman Skuli Tostesson was the most influential advisor to Olav Kyrre. The royal income was also taken from foreign models. The penances played an important role in this. The English Queen Mother Alfiva tried to transfer the English income system completely, which ultimately accelerated the expulsion of her and her son Sven after the death of Canute the Great.

In addition there was the idea of kingship propagated by the church as supra-personal and supra-temporal rule and the associated institution of a timeless empire independent of people. The canonization of kings, who thus not only became saints, but were also understood as mythical protectors of the empire, symbolized this context . The kingdom was conceived as the property of the canonized king, and his successors were his trustees on earth. The old pagan idea of the empire as an association of persons was taken up, but at the same time transformed into a timelessly valid institution . The same process can be observed in Bohemia on St. Vaclav and in Hungary on St. Stephen . In Scandinavia, Denmark received Knut the Saint and Sweden Erik the Saint with a similar function. At the same time, territory and state began to grow together under the umbrella of kingship.

Christianization

The Christianization of Norway was a long process with a long lead time. This process began with the contact of the Norwegian Vikings with the Frankish Empire and the British Isles, which had been Christianized centuries earlier. The colonization of Northern Scotland and Ireland by Norwegians brought about a mixed culture, which in the religious area also brought about a mixed religion, which then gradually developed into Christianity. Since the Christians were not allowed to trade with pagans or to accept pagan servants in their retinue, the custom of primsigning arose . The persons were marked with the cross, which actually meant the inclusion in a catechumenate as an introduction to baptism, but here it was only a formal act without the inner sympathy of the person concerned. The primsigning meant at the same time that the person was accepted by Christians, but could also maintain the usual intercourse with the Gentiles. This usefulness moved many to embrace primsigning without changing their attitude.

The development towards Christianity can be seen both in the grave goods and in the building stones . While grave goods were plentiful in the pre-Viking era, the Viking Age began to decrease, which suggests that the buried no longer needed objects to survive after death. In addition, amulets in the shape of a cross are increasingly found. The building blocks change their shape and function. Originally without writing and often in phallic form in the open, they were at least fertility idols. They were later set up at the roadsides and assigned to graves.

In the Hávamál it says:

Building stones are seldom along the way if the relative does not erect them.

There are building stones in which the graves are empty because the dead were reburied in Christian cemeteries. This shows that the building stones were erected for Christians before the institutionalization of Christianity. Gradually, inscriptions appear on the building stones, which briefly report who built the stone for whom. The continental European custom of gravestones with inscriptions was evidently the model here. At the end of the development there are memorial stones in the shape of a cross. The frequency of these stones suggests a greater number of Christians in the 10th century.

If Claus Krag and the historians who followed him are right in their analysis of the Ynglingatal, that it contains elements that presuppose a worldview that can only be assumed in Norway for the 12th century, and the philologists in the wake of Christopher D. Sapp, that If the philological findings in the Ynglingatal clearly point to the 10th century, then this allows the conclusion that the scholars of the 10th century in Iceland and Norway had more knowledge of the worldview of Central Europe than previously assumed, which also in the Would be important with regard to Christianity.

The first missionary king was Håkon the Good , who had been brought up in England by the Christian king Æthelstan. His father Harald Hårfagre can therefore not have been anti-Christian. It is controversial whether Håkon actually did missionary work and brought priests and even a bishop from England, as Snorri reports, or whether his Christianity was not more of a purely personal nature. But Snorri's news goes well with a source from Glastonbury Monastery in south-west England. A Sigefridus norwegensis episcopus is listed in a register of the bishops associated with the monastery . The context of the list proves that this list dates from before Olav Tryggvason. Øyvind Skaldespiller wrote about Håkon:

The cattle die,

the relatives die,

the land is deserted.

Many men have been enslaved

since Håkon went

to the pagan gods

.

This refers to his entry into Valhalla after his fight, where Odin welcomes him kindly because he spared the pagan sacrificial sites. This is the first written evidence of the word heiðin (pagan) in Norrøn language literature. The word came from English and there translated the Latin paganus , which actually means man in the country . This change in meaning can be traced back to the observation that the people in the countryside remained pagans much longer than the townspeople. From the mouth of a pagan, this word creation throws light on the awareness of the contrast between Christians and pagans. In any case, the opposition between Gentiles and Christians had now entered the general consciousness. At the same time, the influence of Christianity is noticeable: During this period, the sir are often referred to as the "powers" and "forces" that control the world. In parallel to Christ, Thor is now referred to as hinn allemáttki áss , ie "omnipotent Ase". The contrast between Christians and pagans could develop into hatred and contempt. An unknown skald of Iceland wrote about Þorvaldr viðforli (the well-traveled ), who had returned to Iceland as a Christian in 980, and his friend Bishop Fredrik, who wanted to evangelize Iceland:

The bishop

bore

nine children

and Þorvaldr is

the father of all.

This should be an allusion to "children of God" and 9 converts, and the bishop's costume could also be viewed as feminine. Also, one missionary carried no weapons, another unmanly train. In addition, a homosexual relationship between the two is also suggested. There are other anti-Christian poems from this period. The Skaldin Steinunn Refsdóttir Thor praised the fact that he had the ship of the missionary Þórbrandr crashed into the storm. But Christianity could not be stopped, and so many skalds, who had previously praised Thor and the sir, now composed songs of praise to Christ.

In any case, due to the determined resistance, Håkon gave up his missionary attempt. One reason may also have been that his main political support was Sigurd Jarl. What he thought of Christianity is not known. But at least his son Håkon Jarl fought firmly against Christianity. This resistance may also have been due to the persistence of the free farmers in the Trønderic Thing Assembly. The archaeological evidence of the tombs shows that Christianity was on the rise in Vestland , while pagan burial rites continued to dominate the inland districts and Trøndelag for a long time until the 10th century.

The pagan reaction took place under the rule of Håkon Jarl. He undertook to revive the old pagan customs, but was driven out by Olav Tryggvason. Olav's commitment to Christianity before Olav the Holy was put in parallel with John the Baptist and Jesus in later reports.

Christianization came to a preliminary conclusion under Olav Tryggvason, and finally under Olav the Holy. The associated social changes were great. In addition to the king, only the church appeared as an institution. The Latin alphabet was introduced and made it possible to write sagas and poetry. Lent and public holidays were to be observed. The period of life cults were now replaced by baptism, monogamous marriage and burial. All of this happened quite abruptly in a few decades, which would have been inconceivable without the long lead time. Nevertheless, it cannot be assumed that people actually renounced the faith of their fathers in a short time. A long period of syncretism can be assumed, which is also expressed in the mixture of pagan and Christian grave goods. The organization of Christianity with bishops at bishoprics led to a strong religious gradient from town to country. At the same time, one should not underestimate the attractiveness of Christianity to the chiefs and free farmers, who are the cultural bearers of the country. In addition to the rational, demythologizing, closed and systematic world of thought of Christianity, the anthropomorphic stories of the gods could not exist memetically . On the other hand, belligerent men considered Christianity to be shameful and a Christian a disgrace to the family. So you are dealing with an overlapping entanglement of opposing currents. But here, too, Christianity had an offer: While the redemption death of Jesus is the focus today, at that time Christ, who triumphed over death and especially over a concretely presented devil, who first descended into hell and burst its iron gates, became the devil in chains put in the foreground, freed the holy people and now participated in the rule of God. All of this was taken from the apocryphal Gospel of Nicodemus, which was widespread in the Middle Ages . This gospel was even translated into Norrøna under the title Niðrstigningarsaga in the 12th century . At the same time, the pagan gods were not denied, but reinterpreted as devilish demons. An important mission argument was that these gods had lost their power through the victory of Christ. The failure of Olav the Good in his government is also attributed in the sagas to the fact that he was too timid in establishing Christianity by sparing the pagan places of worship. The violent conversion, which seems unchristian to us today, was beyond the momentary and concrete compulsion also an impressive argument in the dispute between the Christian God and the heathen gods, who were unable to protect their followers. Behind this was also the struggle for the national unity of Norway against the threat from Denmark.

The main thrust of Christian mission came from England. When Harald Blåtand boasts on the Jelling stone that he "made the Danes into Christians " and that his Danish kingship also extended directly to eastern Norway, while in the west he only held a more or less abstract upper kingship, one can certainly assume that that this sentence also applies to eastern Norway and western Sweden. However, there is no evidence of this in these areas. On the other hand, Olav Tryggvason's concentrated efforts there indicate that he perceived the missionary zeal of Harald Blue Tooth there as a threat to Norway that had to be fought off. The fact that the mission of the west Norwegian coast was mainly from England may also be the historical core of the legend of St. Sunniva , the first Norwegian saint. As a pious Christian Irish king's daughter, she is said to have fled to Selja in Norway from the pursuit of a pagan suitor, where she was also attacked by pagan Vikings. She fled to a cave and after praying for help, a rockfall spilled the cave entrance. In the time of Olav Tryggvason one was led to the cave by miraculous signs and there the undestroyed fresh corpse was found. However, it belongs to the 11th century and cannot give any information about the mission in the 10th century. However, since the English Church was completely under the decisive influence of Canute the Great, this also meant a danger to Norway's independence. Therefore, the first contact was made with the Archdiocese of Hamburg-Bremen. Bishop Grimkel from the hirð Olafs probably traveled to Bremen before 1025 to subordinate himself and the Norwegian church to Archbishop Unwan. The first trips to Rome by Norwegians began under Olav the Saint. Einar Þambarskelfi ("bow shaker"), a rich man from a noble family and the most powerful man in Trøndelag, first went to King Canute in England in 1023 and then to Rome. He was neutral towards Olav the Holy, did not fight him, but neither did he stand up for him. After Olaf's death, however, he campaigned for his cult of saints and, together with Bishop Grimkil, transferred his body to Nidaros. The skald Sigvat Þordarson, a close advisor to Olav the Saint, also traveled to Rome. Later he composed a price song for Olav. He and Magnus the Good are considered to be the originators of the elevation of Olav to national saint, an important prerequisite for the independence of the Norwegian Church.

The church organization developed. The first missionary bishops did not yet have a clearly defined diocese or a fixed seat. They were all formally consecrated on Nidaros. Under Olav the Holy, the building of the church was first promoted. According to the resolution of the Mostarthing of 1024 cited in Christian law , there should be a church in each district , the "fylkeskirche". The church organization was then refined by building "fjerdingskirker" (quarter churches) and "åttingskirker" (eighth churches) according to the division of the county. However, it may well be that this provision is a construction program that is not always carried out. It is not even certain whether "åttingskirker" were even built. But soon the "fjerdingskirker" were also referred to as main churches. The situation in Ostland is confusing. There were districts that were divided into three sub-districts, so that there were "tredingskirken". These were all official churches with their own property to maintain the church and pay the priests. The property usually came from the crown estate.

Archeology has shown that the churches placed on pre-existing Christian cemeteries. First of all, wooden churches were built. They were later replaced by much larger stone churches. The approximate standard dimensions for the wooden church can be assumed to be 11.50 m wide and 27 m long. For the stone churches, on the other hand, a width of 11.50 and a length to the apse of 27 m were normal.

There were also the farmers' own churches, which were called Hægendiskirker (= comfort churches ). In the 13th century there were over 1,000 churches across the country. After the oldest Borgathingslov, the occupation rights of all churches belonged to the peasants. The bishop later acquired this right for the official churches. This is the state in all later laws. In contrast, the priests in the private churches belonged to the farmer's household. But that soon changed, and already in Gulathingslov the priests of the private churches are on an equal footing with the priests of the public churches. The law required priests to baptize, hear confession, and properly conduct worship. This provision suggests that this was not generally the case. He also had to monitor the church calendar. If he messed up the festive season, the bishop had to pay a fine of 3 marks, because such carelessness could turn the congregation into lawbreakers. Should he incorrectly state the fasting days or holidays more than once a year, the bishop could depose him. The bishop supervised the priests and their equipment, including tools and missals. This shows that church officials across the country were very quickly subjected to strong discipline. In these circumstances, it was difficult to build a qualified priesthood quickly enough. Most of the priests therefore initially came from England. But soon cathedral schools were founded at the bishopric, where the prospective priests also had to learn Latin. The church rules over the year and in particular the very far-reaching marriage laws intervened deeply in the lives of all residents and led to a complete redesign of the course of life.

A large number of inscriptions from the 11th century suggest a great religious commitment by women. The view that the sexes are equal before God must have been a great attraction for them, as must first the restriction and then the prohibition of child abandonment.

The bishops were the driving force behind the internal development of Norway. The centralistic and hierarchical church was also a model for the organization of the state. Their ministry forced them to be out and about because they had to dedicate churches, give confirmations and visit parishes. Therefore they were well informed about the conditions in the country. They leaned on the king, and the king leaned on them. Hamburg-Bremen had held the archbishopric of the Nordic countries since the 9th century. But the Norwegian bishops had connections mainly to England during the missionary period. The rule of the north German bishop had only a limited influence on the situation in Norway. Adalbert even wanted to increase his archbishopric to a northern European patriarchate. Since Magnus the Good encountered repeated opposition after his coronation in 1041/1042, he sought a solidarity with the archbishop. Therefore he also brought a German bishop to Norway, Bernhard "den sakslanske" (= the German). When Harald Hardråde took over, the collaboration ended abruptly. His successor Olav Kyrre was looking for a better relationship with the Archbishop of Bremen. During his reign, the Norwegian church organization began to take shape. The bishops were assigned dioceses that were based on administrative districts of the thing associations. Bishop Bernhard became bishop in the Gulathings district. The official bishopric was Selja (just above the Nordfjord), where the relics of St. Sunniva were. First a small wooden church, later a large stone Christ Church was built as a bishop's church. But soon he went to Bergen, where he also died. Since then, Bergen has been the bishopric. But he must also have resided in Stavanger. However, the bishopric was divided around 1025 and Stavanger got its own bishop.

In the Frostathings district the given center was Trondheim, called Nidaros in the church context. In the time of Adam of Bremen there were six churches in the city, and Olav Kyrre built the Christ Church as a cathedral for the bishop. Around 1100 a Benedictine monastery was added in Nidarholm . A bishopric was built in Oslo for the east. The Bishop's Church was St. Hallvards Church, completed around 1130. A monastery was also built there in the first half of the 12th century.

The church was no longer so closely tied to the king as it was before. In addition, the introduction of the church tithe gave the church a solid financial basis. The tithe was apparently introduced in Nidaros under King Sigurd Jorsalfare. It was paid for farming, livestock farming and fishing. It was divided into four equal parts, one quarter each for the bishop, the priests, the building or maintenance of the church and the poor. In return, the fees for individual church activities were abolished. Before that, believers had to pay pride fees for baptism, marriage, visits to the sick, and burial.

Another consequence of Christianization was the pilgrimage. Harald Hardråde is said to have visited the Holy Land in 1034 and came to Jerusalem to visit the Church of the Holy Sepulcher and other well-known pilgrimage destinations. According to the pilgrimage, he is said to have also bathed in the Jordan. Jerusalem was the main pilgrimage destination from the north, although not the most frequently visited. A special feature was that women also undertook such pilgrimages. There are 700 Scandinavian pilgrim names in the Reichenau Monastery . The most frequent destination of travelers was Rome. However, it was not always a question of pilgrimages, but also of the tasks of church and order administration. In particular, the Scandinavian Birgitten Order with its mother house in Rome gained importance in the 14th century . In second place in terms of frequency was Santiago de Compostela . Many wills and transactions have come down to us that were used to finance these vast pilgrimages. We therefore know more about the great pilgrimages than about the short ones, which did not require any major financial effort. You can find pilgrimage signs from many places of pilgrimage that are not mentioned in written sources, for example Neuss, Königslutter, Marburg and Trier. Within Scandinavia, Trondheim was home to the relics of St. Olav is the most important pilgrimage destination. Then came Vadstena , especially in the later Middle Ages . The miraculous legends according to St. Birgitta and her daughter Katharina are an important source for the daily life of Scandinavians and pilgrims. There were also other places of pilgrimage of regional importance, but not all of them have survived. The place of pilgrimage Hattula is named in Queen Margaret's Testament , which indicates a greater significance.

See also

- The time before: History of Norway before Harald Hårfagre

- The connection is Norway in the Christian Middle Ages

literature

- Anton Wilhelm Brøgger , Haakon Shetelig : Vikingeskipene. Their forgjengere and etterfølgere. (Viking ships. Their predecessors and their successors) Oslo 1950.

- Johannes Fried : Why Norman rulers were unimaginable for the Franks. In: Bernhard Jussen (ed.): The power of the king. Rule in Europe from the early Middle Ages to modern times. Munich 2005, ISBN 3406532306 , pp. 72-82.

- Anne-Sofie Gräslund: Arkeologi som källa för religionsvetenskap. Några reflectors om hur gravmaterialet från Vikingatiden can be used. (Archeology as a source of religious studies. Some reflections on how grave material from the Viking Age can be used) In: Nordisk Hedendom. Et symposium. Odense 1991, pp. 141-147.

- Kim Hjardar: Harald Hårfagre og slaget ved Hafrsfjord. In: Per Erik Olsen (Ed.) Norges Kriger. Pp. 10-17.

- Per Erik Olsen (Ed.): Norges Kriger. Fra Hafrsfjord to Afghanistan . Oslo 2011, ISBN 978-82-8211-107-2 .

- Jón Viðar Sigurðsson: Det norrøne Samfunnet. Vikingen, Kongen, Erkebiskopen and bonding. Oslo 2008.

- Oluf Kolsrud: Noregs kyrkjesoga . (Norwegian Church History) Vol. 1: Millomalderen, Oslo 1958

- Claus Krag. Ynglingatal and Ynglingesaga: a study in historiske kilder. (Ynglingatal and Ynglingesaga. A study of historical sources.) Oslo 1991.

- Claus Krag: Vikingtid og rikssamling 800–1130. In: Aschehougs Norges Historie Vol. 2. Oslo 1995.

- Christian Krötzl: "The nordiska pilgrim cultures under medeltiden." In: Helgonet i Nidaros. o. O. (1997), pp. 141-160.

- Vidar Alne Paulsen: Stormenn og elite i periods 1030–1157. In the undersøkelse of stormenns bakgrunn, maktgrunnlag and strategist in case of conflict . Bergen 2009.

- Fritz Petrick: Norway . Regensburg 2002.

- Christopher D. Sapp: Dating Ynglingatal. Chronological Metrical Developments in Kviduhattr . In: Scandinavistik 2, 2002, pp. 85–98.

- Wolfgang Seegrün: The Papacy and Scandinavia. Neumünster 1967.

- Niels Petter Thuesen: Norges historie i årstall. (Norway's history in years) Oslo 2004.

- Thomas Zotz: How the type of sole ruler (monarchus) was implemented. In: Bernhard Jussen (ed.): The power of the king. Rule in Europe from the early Middle Ages to modern times. Munich 2005, ISBN 3406532306 , pp. 90-105.

Footnotes

- ↑ a b Kim Hjardar p. 11 and endnote 3.

- ↑ Kim Hjardar p. 12.

- ^ Fried p. 72

- ↑ Petrick p. 32

- ↑ Sigurðsson 2008 p. 12 with further references from other historians.

- ↑ Zotz p. 101 ff.

- ↑ Krag p. 95

- ↑ Krag p. 97

- ↑ On the previous one: Krag p. 101

- ↑ Kolsrud, Kirkjesoga IS 124; Sea green p. 80

- ↑ Brøgger / Shetelig p. 201.

- ↑ Brøgger pp. 213, 275

- ↑ Petrick p. 38 f.

- ↑ Paulsen p. 38.

- ↑ Petrick p. 38

- ↑ Gräslund p. 143.

- ↑ Krag 1991

- ↑ Sapp 2002

- ↑ In the Borgund Church ( Sogn og Fjordane ) there is a stone from this time: Þórir carved these runes on the evening of Olaf's mass (July 28th) when he passed here. The Norns bring both good and bad. With difficulty they created me (the runes). Norse Runeinnskrifter 351.

- ↑ Krötzl p. 145.