Vikings

As Viking 's relatives warlike, seafaring groups of mostly be Nordic peoples of the North and Baltic Sea region during the Viking era (790-1070 n. Chr.) In the Central European Early Middle Ages called.

In the contemporary perception, the Vikings only represented a small part of the Scandinavian population. Two groups can be distinguished: One of them carried out robbery close to the shore from time to time and at an early stage of life. It was young men who broke out of their home ties and sought fame, fortune and adventure in the distance. They later settled down like their ancestors and ran the local economy. The sagas ( Old Norse literature ) and the rune stones tell of them . For the others, robbery close to the bank became part of their life. One encounters them in the Franconian and Anglo-Saxon annals andChronicles . They soon did not return to their homeland and could no longer be integrated into their home society. They were fought there as criminals.

The term Vikings

Word origin

The word Viking is probably derived from the Old Norse noun víkingr (masculine), or fara i viking (to go on a pirate voyage), which means "sea warrior who takes a long journey from home". The feminine víking initially only meant the long journey by ship, later also the "war voyage at sea to distant coasts". However, this is already the final stage of word development. The word is older than the actual Viking Age and is already used in Anglo-Saxon Wídsíð .

On the other hand, the news about the attacks by Scandinavians on the North Franconian coasts during the Merovingian era probably mentions sea kings, sea gauts and sea warriors, but never Vikings. A series of raids into England began at the end of the 8th century , but it was not until 879 that the word Vikings was used in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle to refer to this warlike activity. After that it appears only three times, namely in the records for the years 885, 921 and 1098. So it was not a common expression, not even during the time of Danish rule over parts of Britain. In addition, although Vikings are used today to mean Scandinavians, the word was used quite generally in the translation of the Bible and in classical literature for pirates . In any case, the term Viking appears relatively late on Swedish rune stones , the feminine expression víking for the Viking march in the composition vestrvíking even at a time when the robbery expeditions to the east had apparently already ceased, because the corresponding word austrvíking does not exist. Viking is documented on Danish rune stones for the beginning of the 11th century.

The origin of the word is therefore disputed. The Germanic vík describes a “large bay in which the shore recedes”, according to some researchers the original settlement area of the Vikings. It is unlikely to be traced back to this root, because calling into bays and settling in bays was a common practice and nothing that specifically distinguished the Vikings. The Vikings usually settled on islands: on the Île de Noirmoutier in the Loire estuary ( Loire-Normans ), on the island off Jeufosse (today: Notre-Dame-de-la-Mer ) and the "île d ' Oissel ”in the Seine (Seine-Normannen), on the island of Camargue in the Rhone delta , the Walcheren peninsula in Zeeland , the Isle of Thanet , the Isle of Sheppey and others, but especially on the Orkney Islands to the west and north of Scotland and those in the Irish Sea ( Isle of Man ) or on Groix (where boat graves were found).

Another theory derives the term Viking from the Latin word vīcus , which means a place. Reference is made to the many city names that end in -wik . However , this does not explain the feminine abstraction víking . Vik is often referred to as the old name for the Oslofjord . So originally they were pirates from Vik. For the most part, this is considered unlikely, as people from Vik are nowhere particularly prominent as pirates. For an acceptable derivation, the more recent research establishes the condition developed by Munch that with it the feminine abstraction víking for “Viking train” can also be explained as a parallel development. The stated declarations cannot meet this condition.

It is also considered that the root should not be found in Scandinavian but in Anglo-Frisian, since it appears in Old English glossaries from the 8th century; in this case, a derivation from Old English wíc “camp place” (but also “dwelling place, village”, ultimately also borrowed from the Latin vīcus “village, property”) seems likely. This derivation cannot explain the feminine abstraction either. Other word derivations go from vikva “move away from the place, move, move” or víkja (from Norwegian vige “ move ”). This includes the word vík in the expression róa vík á "rowing a curve, while rowing off course". Afvík means “detour”. The feminine word víking would then be a deviation from the right course. Synonymous with this in the texts is úthlaup "the journey, the departure from land". úthlaupsmaðr also means Viking and úthlaupsskip pirate ship. Víkingr would then in turn be someone who escapes from home, i.e. stays in a foreign country, goes on a long sea voyage. This derivation has not met with general approval because it is based on a level of abstraction that is too high.

A new attempt at an explanation includes the word vika in the considerations. This word lives on in the German word “Woche” and has both a temporal and spatial meaning: It is the distance that a rowing team rowed until the change to the oars. In Old West Norse, vika sjóvar is a nautical mile. From this the suggestion is developed that víkingr is a change or shift rower and the abstract víking means "rowing in shifts". The lack of an original masculine noun from the word vika is explained by the fact that the feminine word víking came first and víkingr was a secondary derivation. This declaration is under discussion and has not yet caught on. Ultimately, there is no agreement on the origin of the word Viking .

Concept development

Vikings was never an ethnic term, though modern writers also envisioned them geographically in the south and west, not so much in the east of Scandinavia.

The words víkingr and víking have developed different meanings. While víkingr was soon no longer used for noble people and ruling kings because of its increasingly negative connotation, it could certainly be said of these that they lead to víking . King Harald Graumantel and his brother Gudröd used to go to Víking in the summer “in the western sea or in the eastern lands”. These Viking trips were either private looting companies of individuals, or they joined together in organized associations. But the trips did not necessarily involve robbery. In the Gunnlaugr Ormstungas saga , the hero goes on víking and first visits Nidaros , then King Æthelred , then travels from there to Ireland , to the Orkneys and to Skara in Västra Götalands Län , where he stays with Jarl Sigurd for a winter, most recently to Sweden to King Olof Skötkonung . There is no talk of looting.

In terms of conceptual history, two phases of the conceptual content can be identified: an early historical phase in the Old Norse texts up to the 14th century and a modern phase, which can be traced back to the 17th century.

Anglo-Saxon sources

The word vícing is probably first found in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle . There it occurs together with the words scip-hlæst (= ship's load) and dene (= Dane). The bodies of the men are known as ship cargo. In 798 the attackers were still referred to as Danes . In 833 the attackers were “shiploads of Danes”. It is striking that there is talk of xxxv scip-hlæst and not of 35 ships. The accent is placed on the men. In 885 the shipments were then called Vikings. In the 9th century, in accordance with the origin of the word and apparently supported by Widsith , the Vikings were considered pirates. The fact that the chronicles did not immediately name the Danes Vikings suggests that they were not initially expected outside their immediate vicinity. The late 10th or early 11th century poem The Battle of Maldon portrays the Vikings as a ransom-demanding warband.

þa stod on stæðe, stiðlice clypode

wicinga ar, wordum mælde,

se on beot abead brimliþendra

ærænde to þam eorle

þær he on ofre stod

A Viking messenger stood on the bank,

called out bravely, spoke with words,

boastfully brought the sailor's message

to the count of the country

on whose coast he was standing

Archaeological finds suggest that the word wícing is essentially the same as it is used in the poem Widsith (the verse is quoted in the article there): They are predatory attackers. They are equated with the Heathobearners in the verse quoted . What this is all about is unclear. Verses 57-59 bring a table of peoples:

Ic wæs mid Hunum

ond mid Hreðgotum,

mid Sweom ond mid Geatum

ond mid Suþdenum.

Mid Wenlum ic wæs ond mid Wærnum

ond mid wicingum.

Mid Gefþum ic wæs ond mid Winedum

ond with Gefflegum.

I was with the Huns

and with the Reidgoten I was with the

Svear and the Gods

and with the Southern Danes

with Wenlum , with Väringers

and with the Vikings.

I was with the Gepids and with the Wends

and with the Gefflegern.

Whoever was meant by the name in detail, the table clearly points to the Baltic Sea region, and the Vikings certainly refer to northerners.

Around the same time there is a poem about the Book of Exodus, in which special emphasis is placed on the struggles of the Israelites and which is passed down in the Junius manuscript . It's about the passage through the Red Sea in army formation with white shields and fluttering flags. It says about the Ruben tribe :

æfter þære fyrde flota modgade,

Rubenes sunu. Randas bæron

sæwicingas ofer sealtne mersc,

manna menio; micel angetrum

eode unforht.

After this crowd comes a proud sea warrior,

Rubens son. Sea Vikings , numerous men,

carried their shields across the salty sea,

a select group that walked

without fear.

These two pieces of evidence show that the term Viking in the sense of sea warrior was used before the North Germanic expansion into England and therefore does not cover the conquests initiated by a king. At the time, private-initiative robbery near the bank was the most significant experience with the Vikings. This was before the actual Viking Age. The organized invasions to expand rule in the Viking Age were attributed to the Norsemen and Danes , but not to Vikings . The association of the term Vikings with a sea-based attack can be observed throughout the Anglo-Saxon sources. They are inseparable. A distinction is even made between land armies and Vikings. In the chronicle of the year 921 the battle of the Danish army in East Anglia against Edward is reported as a battle of the landheres ge thara wicinga (the land army and the Vikings). Both groups were Danes and the ships supported the land army.

The connection between WIC = bay and wicing is in the military fortifications in Vig Gudsø the small belt and in the vicinity of Kanhave channel , the island Samsø at its narrowest point of the Sælvig bay in the Stavns fjord dendrochronologically average (construction on 726 dated). It fits that in the Widsith (verse 28) the word wicing is placed parallel to sædena = sea-Danes . On the handle of an ax that was found in Nydam there is a runic inscription, which the names Sikija (one who lives on the Sik, a wetland, as it is often found next to a bay) and Wagagast (wave guest, seafarer) includes. From this one can conclude that the population there was heavily related to the lake topography. Although boats and weapons appear to have belonged to sea warriors in Nydam, no definition of a Viking can be derived from the finds.

In Irish texts the word Vikings occurs as a loan word uicing , ucing or ucingead .

Old Norse literature

The introduction of the personal name víking shows that the term soon became associated with personal qualities and signaled a certain identity and not a certain type of war. However, it is noticeable that the personal name is only used in Norway, eastern Sweden, Småland, Finland and Scania, but was not used in Iceland, at most as an epithet ( Landnámabók ). Eilífr Goðrúnarson (2nd half of the 10th century) calls the warrior gods “ Vikings ” in his Þórsdrápa .

Óðu fast (en) fríðir

(flaut) eiðsvara Gauta

setrs víkingar snotrir

(svarðrunnit fen) gunnar;

þurði hrǫnn at herði

hauðrs rúmbyggva nauðar

jarðar skafls at afli

áss hretviðri blásin.

Gautheims Wiking, brave,

Wat'ten, warriors,

confederates, noble ones .

Erdschwart'-wet swelled harder.

Well'gen Lands violent wave roars

, storm-disheveled,

Hin much on the

rocks-Felds-Herren Notmehrer.

With this name, virtues of the past are to be evoked: A loyal and brave sea-bound warrior, busy with external acquisition . In skaldic the oldest use in is Egill Skallagrímsson find (910-990):

Þat mælti mín móðir,

at mér skyldi kaupa

fley ok fagrar árar

fara á brott með víkingum,

standa upp í stafni,

stýra dýrum knerri,

halda svá til hafnar,

Höggva mann ok annan.

My mother said

I deserved a warship

Soon with sprightly men

to fetch robbery than Vikings.

I have to stand at

the stern, steer the keel boldly:

Like a hero in the harbor,

I hit the men.

Egill is not yet twelve years old and with this poem he is responding to a corresponding promise from his mother. Egill represents the saga type of the Viking. He uses the word in many skald stanzas. Apparently this heroic conception of Viking life had a long tradition at the time the poem was written (around 920). It is noticeable that neither the social background, the families of the participants or the motives of the Viking movement, nor their legal or military structures are the subject of tradition.

But soon the pejorative importance prevailed, especially in Sweden, when trade took a priority there, because the Viking was the greatest danger for the merchant. This is one reason to distinguish the Viking from the merchant for this time, even if the same person might have worked as a Viking or as a merchant depending on the prospect of profit. But these are isolated cases. In general, the Vikings seem to have had less importance in the Baltic Sea area. If it is correct that the Leidang has its origins in Sweden, there was soon not much leeway for private raids. Rather, the campaign there was under the control of the king very early on. So the private initiative had to focus more on trade. The term “ Varangians ” , which is strictly limited to this area, was used for the eastward journeys into the rivers of Russia .

In Norway, action was soon taken against the Vikings in their own country. Sigvald the skald testifies in his memorial song about Olav the saint that he acted mercilessly against robbery in his own country:

Vissi helst, það er hvössum

hundmörgum lét grundar

vörðr með vopnum skorða

víkingum skör, ríkis.

Land's patron with swords

pounded the heads of

many of the Viking people.

He was terribly in power!

Rune stones

In Old Norse texts on rune stones of the 11th century there are neutral and awe inspiring meanings. The word Vikings is associated with ideas of honor and oath. The word was simply equated with drengr = brave, honorable man. In these texts there is no Viking behind a plow. He was presented as a stranger with sword in hand.

At the same time, the translated Latin literature mentions pirates, robbers, and other villains Vikings . In the early stages, the word was used by non-Scandinavians and Christians in a pejorative sense with a certain amount of reverence. Vikings were violent attackers. Adam von Bremen writes: “They are really pirates that those Vikings call, we ash men.” He calls the pirates Ascomanni several times .

The word Viking does not appear in the West Franconian sources . Instead, the raids consistently speak of Normans . Contemporary annals mention their cruelty. In the more locally oriented hagiography , the incredible cruelty emerges as a special feature.

The Viking cruelty is not explicitly mentioned in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle . But this is related to the subject matter and the intention to depict the rise of the House of Wessex and the struggle of Alfred the Great .

Christian Middle Ages

After 1100 the term Vikings was used more and more pejoratively. This is mainly due to the fact that they did not adhere to the continental rules in military ventures. These basically protected churches and monasteries that were easy prey for the pagan warriors. In this respect, they were close to the Hungarian cavalry hordes in reporting. Here it was not a question of political campaigns to expand power, but, like the Vikings, raids.

The so-called Poeta Saxo equates the Ashmen , whom Adam von Bremen equates with the Vikings, with pirates. Snorri begins his account of the Orcade Jarle in the story of Olav the Saint with the derogatory remark: “It is said that the orcades were settled in the days of the Norwegian King Harald hårfagre . Before that time, the islands were just a Viking cave. ”He doesn't even consider their presence as a settlement. The Heimskringla said about Magnus Berrføtt : "He kept the peace in his country and cleared it of all Vikings and highwaymen." Here the change is shown by the naming of the Vikings together with the outlaws. Erik Ejegod is praised for his courageous intervention against Vikings in Denmark. In the 12th century, in a poem in memory of Olav Tryggvason, Vikings were used synonymously with “robber” and “criminal”. In the poetry of the 12th century, the Viking becomes the enemy of the great and rebels. In the Latin religious literature Vikingr with raptor , praedo translated so on. The term is no longer restricted to Scandinavia, but also refers to pagan enemies far in the south. The same development can be observed in Iceland: In the Landnámabók , the first settlers, ancestors of important families, are still referred to as víkingr mikill (great Vikings). But at the same time the unpeaceful aspect of violence prevails. Þorbjörn bitra hét maður; hann var víkingur og illmenni. (“A man's name was Þorbjörn bitra; he was a Viking and a bad person.”) The noble Óleifr enn hvíti is also referred to as herkonungr ( king of the army ) and not as a Viking. No descendants of the noble families are called "Vikings" themselves. But it is reported by some that they were í (vest) víking , that is, on a Viking journey.

Even the skald Egill Skallagrímsson, who embodied the “classic” type of Viking, is not referred to as a Viking. Only his ventures are called Víking . In the Njálssaga it is reported that Gunnar von Hlíðarendi and the sons of Njál went on a “Víking” trip, but they themselves are not called Vikings. But Gunnar's enemies in Estonia are known as Vikings. In contrast, the saga of Hjorti from Viðareiði, which is believed to have originated on the Faroe Islands, clearly describes the seafarer Tumpi, who comes from a farm known today as Gammelfjols-gård, as víkingr . On a trip to Iceland around the year 1000, he is said to have had a dispute with the lean of the Norwegian crown on the Færøern, Bjørn von Kirkjubø , and was therefore banished from the islands to Greenland .

In the legal texts ( Grágás , Gulathingslov ) the equation with malefactors was then consolidated. The same goes for Sweden. At the same time, in the Viking legends about Ragnar Lodbrok and other sea heroes, idealizing and knightly traits can be found, in which the hero is portrayed as the protector of the weak. In the Friðþjófs saga ins frœkna , the hero Friðþjóf lives a chivalrous buccaneer life in which he destroys the evildoers and cruel Vikings, but leaves farmers and merchants in peace. The same motif of chivalry pervades the Vatnsdœla saga . The fine distinction between the feminine word víking = military journey and the masculine word víkingr = pirate should be pointed out. The chivalrous protagonists set out on a víking voyage, but their opponents are pirates and robbers, from whom they steal the booty that these merchants and farmers have stolen.

Early modern conception

The literary processing in the sagas formed the basis for the early modern view of the Vikings in the course of the Scandinavian identity. The Swedish scholar Olof Rudbeck in particular regarded the Viking as "our strong, warlike, honorable, pagan and primitive ancestor".

Although inferior, it was believed that its best qualities lived on in Sweden and the rest of Scandinavia. In the 18th and 19th centuries, pagan primitiveness was pushed back in favor of a free and law-abiding image of the Vikings. This had the effect in later literature that the regular wars of conquest z. B. in England also ascribed to Vikings and thus equated with the predatory raids on the English monasteries in the 8th century.

It was overlooked that the virtues that were praised in the Vikings were then only practiced in relation to one's own group. Morality was strictly oriented towards one's own clan and followers. Hence the robbery abroad was not dishonorable; on the contrary, it contributed to one's reputation. This distinction is based on Harald Hårfagre's decision to ban the Viking Gang-Hrolf (allegedly identical to Rollo in Normandy ) from Norway. As long as he was army in the East, this was accepted. But when he continued his looting in Vik (Oslofjord), he broke the rules that you were not allowed to loot in your own country. The somewhat belittling view of the Vikings in the early modern period led to the Vikings allegedly operating as farmers and traders and adopting the virtues of the honorable citizen. That was the time when the Vikings gave their name to an entire cultural epoch, namely the Viking Age . When other activities in the arts and crafts were discovered, the term in today's expanse was generally transferred to the seafaring peoples of the North and Baltic Seas, provided they appeared predatory. The term “Vikings” lost its contours. The romantic heroization led to the Vikings being ascribed special skills and knowledge in seafaring. So they should already have the compass and excellent nautical skills. This, as pointed out in the article Viking Ship, is legend.

presence

In the German-speaking world, Vikings did not become a general term for Nordic seafarers until the 19th century. In particular, Leopold von Ranke has probably contributed significantly to the generalization of the concept of Vikings in the 19th century. Before these peoples were called Nordmanns or Normans . Today the Viking term is still used in a very undifferentiated way, as can already be seen on the maps that are offered under the name "The World of the Vikings" and all ship movements of the Viking Age from Vinland in the northwest to the Byzantine Empire in the southeast, from Staraja Ladoga in the northeast to Gibraltar in the southwest indiscriminately ascribed to the Vikings. Boyer's map even includes a Viking pilgrimage to Jerusalem!

Today an extreme counter-movement can be observed in science, which rejects any other activity of the Viking as robbery than that which comes from national romantic historiography. This extreme reduction to robbery, which Herschend advocates, who even wants to exclude any trade, is not followed here. Rather, the “predatory trade” economy must be considered proven for many Vikings of the Norwegian and Swedish upper classes. The Vikings on a raid were then able to settle in other countries. Sometimes these branches and settlements could start new raids. Harald Hårfagre was forced to repel the threat to the Norwegian coasts from Vikings from the British Isles. It is only correct that pure commercial travelers, artisans and farmers - regardless of where they settled - whose life plan was not essentially determined by battle and robbery, should not be called Vikings. The Northmen who settled Iceland and Greenland and discovered North America were not Vikings. Herschend's view only applies to the Vikings, who plagued the Frankish Empire and England in the 8th and 9th centuries. But this is only part of it.

Related expressions for the same group of people

The word Drængr , which can be found on Sweden's rune stones, may have contributed to the rather honorable conception of Vikings . This word underwent a change around 1000. It is often used synonymously with Vikings on the oldest rune stones . At that time, the Anglo-Saxon loan word dreng denotes the warrior. Later it had a more ethical content than a name for a man “of the right grist and grain”, without the need for a trip abroad. In his Snorra Edda, Snorri defines the Drengr as follows:

"Drengir heita ungir menn búlausir, meðan þeir afla sér fjár eða orðstír, þeir fardrengir, er milli landa fara, þeir konungsdrengir, er Höfðingjum þjóna, þeir ok drengir, erð þjóna rð. Drengir heita vaskir menn ok batnandi. "

“Young men are called 'Drengir' as long as they struggle for wealth and fame; 'Fardrengir' those who sail from country to country; 'King Drengir' those who serve chiefs; but they too are 'Drengir' who serve powerful men or peasants; All vigorous and mature men are called 'Drengir'. "

This is where the conceptual change that had taken place up to the time of Snorri can already be seen.

Another name for men with a Viking way of life is likely to have been the early use of the title húskarl . They were free men who joined the mighty and formed their entourage. They enjoyed free maintenance and lived in his house, which therefore had to be a spacious property. For this they were obliged to assist him in all undertakings. If he went on víking , they formed his core force, the lið . Being Húskarl with a powerful man was an honorable job for young peasant sons, especially if those powerful men were a jarl or a king. But under the conditions before and around 1000 such a crowd could only be kept if they had the prospect of fame and fortune, especially since wealth was a prerequisite for high reputation, which could only be achieved through great generosity ("gold spreader" "donor of the rings" were Kenningar for the king.). This happened predominantly on trips abroad that were associated with robbery trade. This is suggested by the complete absence of the title húskarl in the post-Viking Swedish sources.

In the Ynglinga saga, Snorri defines the sea king as follows:

„Í þann tíma herjuðu konungar mjög í Svíaveldi, bæði Danir ok Norðmenn. Voru margir sækonungar, þeir er réðu liði miklu ok áttu engi lönd. Þótti sá an með fullu mega heita sækonungur, he hann svaf aldri undir sótkum ási, ok drakk aldri at arinshorni. "

“There were many sea kings who commanded large armies but owned no land. He alone was recognized with justification as a real sea king who never slept under the sooty roof and never sat in the corner of the stove with drinks. "

This is a typical Viking leader, as the entertainment of such a team requires robbery. To Olaf the Holy , he writes:

"Þá er Ólafur tók við liði og skipum þá gáfu liðsmenn honum konungsnafn svo sem siðvenja var til að herkonungar, þeir er í víking voru, he þeir voru konungbornirþna, þá báarru æændegungse“ löónir konðungsum ðnóir konðungsum.

“When he [12 years old] received an army and ships, his people gave him the name 'King', as was the custom at the time. For army kings who became Vikings carried the royal name without further ado if they were of royal blood, even if they did not yet have any land to rule. "

The very often used formulations (on more than 50 stones) at verða dahður (found death) and hann varð drepinn (he was killed) are only used in connection with death abroad, with one exception. This can point to Viking ventures, but also to trade trips. The merchant ships themselves could become victims of attacks.

There is little evidence of the names of the ship's crews. So there is the expression styrimannr . This is the skipper. What kind of undertakings the ship served can only be inferred indirectly from the few texts. The stone Haddeby 1 from Gottorp indicates, due to the context of the text, more of a warlike use. In contrast, the skipper, who is named on the Swedish stone in Uppsala Cathedral , was on a trade voyage.

Another term for a sea warrior was skípari , shipwright. This can be seen most clearly on the stones from Småland and Södermanland .

The designation in the early written sources of the 8th to 11th centuries in the Franconian Empire does not always allow conclusions to be drawn as to the extent to which the authors differentiated the ethnic groups in the attacks they described. The designation was essentially determined by the intention to make a statement. The Vikings are listed under the collective terms “ Normans ”, “Pagans” and “Pirates”. One can also find the preferred term Danes. Sometimes a distinction is made between Danes, Norwegians and others. In the descriptions of the crimes, ethnic differentiation was not important in the annals. In the case of authors like Nithard and Notker , based on their sources of information, one can assume that they knew about the predominantly Danish origin of the Vikings. Nevertheless, they used the term "Normans".

In hagiography there is a frequent equation of Normans and pagani (pagans). The ethnic affiliation of his opponents was irrelevant for the representation of the exemplary actions of the saint described. When Hinkmar von Reims writes to Pope Hadrian von Pagani Northmanni and to the bishops of the Diocese of Reims about the struggle against paganos , then this author of part of the Annales Bertiniani must have been informed about the ethnicity. In the pastoral literature of letters, naturally, predominantly the term “pagani” is used without any further differentiation.

In annals and chronicles, the term Danes is preferred when reporting on the situation in Denmark. Then there is the synonymous use of Danes and Normans . Other descriptions only name Danes as actors. From Einhard's life of Charlemagne one can read off the knowledge of the different ethnicity of the Normans.

"Dani siquidem ac Suenones, quos Nordmannos vocamus, et septentrionale litus et omnes in eo insulas tenent."

"Danes and Sueons, who we call northern men, have the entire north coast and all the islands in it (meaning the Baltic Sea)."

In the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, a distinction is made between Norwegians and Danes during the Norman raids. The Viking attack in 787 is ascribed to the Danes in the oldest manuscript A. The manuscripts B, C, D, E and F write III scipu nodhmanna . These were the first Danes ( Deniscra manna ) in England. The manuscripts E and F also indicate Heredhalande as the place of origin , which refers to the Norwegian coast.

Other Frankish written sources speak of the Vikings as piratae , but do not use the word Vikings . They do not differentiate between a fleet and a land army. Otherwise, however, the word meanings piratae in the Franconian and wicing in the Anglo-Saxon sources coincide, as they both refer to the connection "ship - attack - plunder".

In Ireland , Vikings were called Lochlannach , which has the same meaning. The historian Adam von Bremen called the Vikings Ascomanni , "ash men". There were ships called askr or askvitul . This may be due to the fact that the ships below the waterline are said to have been made of oak wood, but above the waterline they were often made of ash wood, but this cannot be proven archaeologically with certainty. Erik Blutaxt's brother-in-law was called Eyvindr skreyja ("screamer"), his brother Álfr was nicknamed Askmaðr . The Arabs called the Norse sea warriors who occasionally haunted their coasts al-Majus .

In the Irish annals, a distinction was made between Danish and Norwegian Vikings. The Danish Vikings were called dubh (the blacks), the Norwegian Vikings finn (the whites). This is supposedly due to the color of their shields. From the decisive battle of Olav the Saint near Nesjar, the skald Sigvat reports as an eyewitness that the shields of his men were white. Together they were gall (the strangers). In fact, the shields were often different colors. Long shields in different colors can also be seen on the Bayeux Tapestry.

activities

swell

There are very different sources with very different informative value for the activities of the Vikings. The main sources are:

- Runestones : They contain reliable statements about the people who were immortalized there. However, as far as Vikings are mentioned, they usually date from the 11th century and give little information about the time before that. Older ones contain too little text. On the other hand, they affect most of the people in the Baltic Sea region. The people belong to the upper social class and therefore reflect a very specific Viking image that cannot be generalized.

- Sagas : You portray the Viking image of an upper class. Although they were also written down at a later date, the poems they contain are undoubtedly very old, often contemporary, and have a high source value.

- Annals and Chronicles : They were written in the Franconian Empire and in England. Their source value is often underestimated by accusing them of having been written by monks and therefore giving a one-sided negative image of the Vikings. It can be countered by the fact that the authors were usually very close to the events and there is no reason to doubt the representation just because of its religious background. Incidentally, a close reading shows that there are certainly appreciative passages. But the informative value is limited, as they rarely make quantitative statements. They are limited to the events as such. Essentially, it concerns the Reichsannalen , the yearbooks of St. Bertin , the yearbooks of St. Vaast , the Xantener yearbooks , the yearbooks of Fulda , the chronicle of Regino von Prüm , the deeds of Karl von Notker Balbulus , De bello Parisiaco des Abbo von St. Germain, The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle , De rebus gestis Aelfredi von Asser and the Chronicon von Aethelweard.

- Hagiography and translation reports : This is the most underrated source type. Even if the description of the saint's life lacks a critical distance, the embedding in contemporary events has a high level of credibility, especially since it often agrees with other sources in the description of the events. In addition, the authors often sat in the affected monasteries and were able to follow the events up close. The anonymous Translatio S. Germani and the Miracula S. Filiberti are productive in this regard . They are used here only through secondary literature.

Some scholars still adhere to the radical criticism of the sources and discard all sources for various reasons. They stand in the tradition of radical saga criticism from the beginning of the 20th century. But most of the serious historical research has turned away from it and tried to work out the credible information from the sources through careful text analysis.

Way of life and things to do

The external perception of the Vikings differed radically from their self-perception , whereby only the view of the aristocratic Vikings in the sagas and on the rune stones has been handed down as an internal view . The Vikings plundering France and England have left no evidence of their self-image. Due to the continental perception and tradition, the Vikings received an attention that goes far beyond their importance in intra-Scandinavian history. The Vikings of the saga literature were a phase of the life of some nobles who later found their way back to a normal peasant life. Egill Skallagrimsson ended his life as a farmer in Iceland. The remaining Vikings were a social group that had separated from Scandinavian society. These were only seen as enemies of the greats and the king, so that they only played a limited role - as enemies - in inner Scandinavian history. The sources in their entirety show an extraordinarily divergent picture of the Vikings.

In diplomas of King Ethelwulf of Wessex, which exempted certain monasteries from taxes, the duty of defense against the incredibly cruel, barbaric enemies is exempted. All of the West and East Franconian as well as the Anglo-Saxon source material independently agree that the lust for murder and destructiveness was a prominent characteristic of the attackers. Such a source situation cannot be relativized with reference to the consistently Christian authors, especially since the few Arabic sources from Spain describe the same picture. The smaller sources, especially the hagiographic sources, emphasize this characteristic, while greed is given less attention. This is more likely to be cited in the larger narrative sources.

The Viking image of the 9th century is expressed in the Annales Bertiniani for the year 841 as follows:

"Interea pyratae Danorum ab oceano Euripo devecti, Rotumum irruentes, rapinis, ferro ignique bachantes, urbem, monachos reliquumque vulgum vel caedibus vel captivitate pessumdederunt et omnia monasteria seu quaecumque loca flumini territi Sequanae adhaerentia sunt depopulati multiquer accept."

“In the meantime, Danish pirates attacked Rouen from the North Sea sailing through the channel, raged with robbery, sword and fire, sent the city, the monks and the rest of the people to death or in captivity, devastated all monasteries and all places on the banks of the His or her, after they had given a lot of money, left them in horror. "

The Saxon Wars of Charlemagne during the same period in no way had a formative effect on contemporary thought, although Alcuin sharply criticized his actions against the Saxons. Anyone who recognizes anti-Scandinavian partisanship in the Latin texts overlooks the fact that in the consciousness of the time there was already a distinction between politically motivated campaigns and raids out of greed with senseless destructiveness. The sources of the inner Franconian disputes are usually limited to the term depraedatio (devastation) or devastare (devastate) without a more detailed description of the processes.

“Odo rex in Francia here, Karolus vero rex supra Mosellam. Exhinc hi qui cum Karolo erant Balduinum infestum habuere, et ubique depraedationes agebantur ab eis. "

“King Odo wintered in France, but King Karl on the Moselle. From here, Charles's followers feuded Baldwin and everywhere they wreaked havoc. "

The Normans , on the other hand, say:

"Nortmanni incendiis et devastionibus in hiantes sanguinemque humanum sitientes ad interitum et perditionem regni mense Novembrio in monasterio sedem sibi ad hiemandum statuunt ..."

"But the Normans, striving for devastation and murder and thirsting for human blood, opened their seat in the monastery of Ghent in November to the disaster and ruin of the empire ..."

A different occurrence can certainly be assigned to this different description.

In the old Frisian law (17 Keuren and 24 land rights), which were probably written in the 11th century, the Scandinavian enemies are dealt with. In the 17 Keuren they are dealt with in three paragraphs. In § 10, the Frisians are allowed to go no further to the east than to the Weser and to the west no further than Fli (= Vlie in Friesland between Vlieland and Terschelling) to defend against the pagan armies ( hethena here ; northhiri ) needed. Section 14 dealt with the case that someone had been abducted by the Nordmanns ( nord mon ; dae noerd manne ). In the Low German variant of these Keuren these enemies were referred to as konnynck von Noerweghen , noerthliuden , dat northiere or Noermannen . How these Vikings were seen is shown in Section 20 of the 24 land rights:

“This is the 20th land right: when Northman invade the land, capture and tie up a man, take him out of the country, and then come back with him and force him to burn houses, rape women, slay men, burn churches and what damage can still be done, and if he then flees or is ransomed from captivity, and comes back home and to his people and recognizes his brother, his sister, his ancestral house and home, the farm and land of his ancestors, then he went to his own property with impunity. If someone invites him to the thing and accuses him of this crime of great misdeed, which he previously committed with the Vikings (mith tha witsingon), then he must appear at the thing and speak openly. And he has to swear an oath there on the relics that he only did all this under duress, as his master commanded him when he was a man who could not control life and limb. Then neither the people nor the bailiff is entitled to accuse him of guilt or a crime because the bailiff was unable to keep him at peace; the unfree had to do what his master commanded him for the sake of his life. "

In general, many of the locals seem to have moved into the Viking hordes by force or as collaborators. In the case of the women mentioned in the report on the occupation of Angers by Vikings in 873, it is assumed that these were not women from their homeland, but parts of the booty:

“Quam cum punitissimam et pro situ loci inexpugnabilem esse vidissent, in laetitiam effusi hanc suis suorumque copiis tutissimum receptaculum adversus lacessitas bello gentes fore decernunt. Protinus navibus per Medanam fluvium deductis muroque applicatis, cum mulieribus et parvulis veluti in ea habitaturi intrant, diruta reparant, fossas vallosque renovant et ex ea prosilientes repentinis incursionibus circumiacentes regiones devastant. "

“When they saw that this city was well fortified and impregnable by its natural position, they were delighted and decided that it should serve as the safest refuge for their and their compatriots' troops from the peoples irritated by their attack. Immediately they pull their ships up the Maine and anchor them to the walls, then they move in with their wife and child to live in, mend where it was destroyed, make the trenches and walls and from there into sudden raids break out, they devastate the surrounding area. "

In the immediate vicinity of permanent camps, there was probably contact with the local population. This might even have been the case with sieges. There is no other explanation for the following account of the siege of Paris :

"Dum haec aguntur, episcopus gravi corruit infirmitate, the clausit extremum in loculoque positus est in ipsa civitate. Cuius obitus Nortmannis non latuit; et antequam civibus eius obitus nuntiaretur, a Nortmannis deforis praedicatur episcopum esse mortuum. "

“In the meantime, the bishop became seriously ill and ended his life, and he was buried in a wooden coffin in the city itself. His death, however, did not remain hidden from the Normans: before the inhabitants had known about his departure, the Normans announced from outside that the bishop had died. "

The Frisian law of 1085, which v. Richthofen has published four manuscripts, uses the word “Wikinger” ( northeska wiszegge ) in one manuscript to determine the duty of the neighbors to help in the event of an attack. Another has at this point tha Nordmanum , the third northeska wigandum and the fourth Low German offers northesca gygandum . In the "Seven Magnus Doors" (probably from the 11th century), in which the freedoms of the Frisians were established, it is said:

"Dae kaes Magnus den fyfta kerre end all Fresen oen zijn kerre iechten, dat hia nen hereferd ferra fara ne wolde dan aester toe dir Wisere end wester toe dae Fle op mey dae floede end wt mey dae ebba, omdat dat se den ower wariath deis end of night den noerdkoning end of den wilda witzenges lake floed mey dae fyf wepenum: mey swirde end mey sciolde, mey spada end mey furka end mey etekeris order. "

“Magnus then chose the fifth Küre - and all the Frisians agreed that they would not go any further on any army voyage than eastward to the Weser and westward to the Fly and no further into the country than to the flood time and back to the time of the ebb, because They protect the seashore day and night from the Nordic king and the tide of the wild Vikings with five weapons: with sword and shield, with spade and fork and with the point of the spear. "

The prisoners were used to build fortifications. In the Miracula S. Benedicti of the Adrevald of Fleury (written shortly after 867) it is reported that Christian prisoners had to build a permanent camp while the Normans recovered.

On the other hand, the bravery and perseverance of the Vikings are well recognized. In the heroic poem about the Battle of Maldon, in which the Norwegians achieve a decisive victory, they are portrayed as brave sea heroes. Regino von Prüm pays tribute to the bravery of the Vikings. In his chronicle for the year 874 he describes the encounter between Vurfand, a vassal of King Solomon , and the Viking Hasting. The two meet equally and respect each other as members of the same caste. In 888 he begins the description of the siege of Paris with the appreciative sentence:

"Eodem anno Nortmanni, qui Parisiorum urbem obsidebant, miram et inauditam rem, non solum nostra, sed etiam superiore aetate fecerunt."

"In the same year the Normans performed a wonderful act during the siege of Paris and an act that was unheard of not only in our times but also in earlier times."

He describes a few lines further that they destroyed the whole of Burgundy through robbery, murder and fire. There can be no question of an anti-Norman, schematic condemnation cliché.

The Franconian sources speak of the enormous booty that the Vikings would have made on their raids. The comparatively modest treasure finds in Scandinavia do not agree with this. The gradual transition to winter camps in Franconia and England shows a social group that has broken away from its native structures and that could no longer be integrated into the developing centralized structures of Scandinavia. The enormous treasures were no longer brought back home. The Vikings, who are described in the Franconian sources, are a different class of people than the one that Egill Skallagrimsson embodies or who is extolled on the rune stones.

The sources do not provide any information about the division of the booty. When the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle of 897 says that those Danes who had no money returned to France on their ships, this indicates that these treasures were apparently not available to everyone to the same extent.

The Viking raids in the Rhineland

In autumn 881 Vikings, who had set up a permanent camp in Elsloo (Flanders), invaded the Rhineland and devastated cities, villages and monasteries in the greater Aachen and Eifel regions. In the spring of 882 a few hundred warriors sailed up the Rhine and Moselle and plundered cities and monasteries there as well. In February 892 another war campaign took place on the Moselle and Rhine.

The leadership

Originally, the Viking kings were sea kings without a land. They were leaders of raids from royal families. They are even said to have wintered on their ships. Because in a meeting between King Olav the Holy and the Swedish King Önund (also Anund , son of Olof Skötkonung ) Olav says: “We have a very strong army and good ships, and we can very well be on board all winter long our ships remain in the style of the old Viking kings. ”But then the sailors refuse to obey him. Wintering on site is out of the question for them.

In the Franconian understanding of the Viking Age, “king” and “people” were already associated with each other. That was still different in the 6th century. The command and disciplinary powers of the military leader at the time were still very limited. When Charlemagne learned in 810 that a fleet of King Gudfred with 200 ships from Nordmannia had invaded Friesland, a main attack on land was expected at his court, so that the emperor was compelled to face this danger personally with an army. Even if the number 200 is exaggerated, a large fleet can be assumed. When he got there, it turned out that the fleet had already withdrawn and Gudfred had been murdered. Since Friesland was viewed by the Jutian rulers as their area of interest, it is doubtful whether Gudfred actually initiated this raid. But at the court of Charlemagne one could not think of anything else with such a large number of ships. The Franks could not imagine the construction of the Danewerke otherwise than that it had been initiated by a decision of the king. Archaeological research has shown, however, that it was built much earlier and in several phases. In 860 and unsuccessfully in the following years, Charlemagne tried to tame the northern groups of men who wandered around the Seine region by paying tribute, promises of loyalty and baptisms, without taking into account that Christianity and feudal law and the "Franconian system" in general. was irrelevant. His successor Karl the Fat also gave their leader ( rex ) Sigfried in 886 a large ransom so that he could break off the siege of Paris. Sigfrid took the ransom and actually withdrew. But some of his troops believed that the booty had been cheated and continued the siege against his will. Two more lost keen their lives. Nonetheless, the siege continued, which suggests that there were more active ones on site. Only small groups operated side by side, there was a single high command at most for joint actions, the authority of the leader was only guaranteed through his success in the raid, even if he came from the nobility. The only really recognized authority over a warrior may only have come from the individual skipper, insofar as this was necessary for handling the ship.

In addition, the Franconian sources use the terms princeps , dux and comes when it comes to smaller units. The group to be commanded does not have to be large. In 896, Hundus entered the Seine with five boats. He is referred to in the Annales Vedastini for the year 896 as dux .

The dynamics of the Viking raids quickly changed, at least in part, into regular military campaigns with a political background. This is what distinguishes them from the Wendish pirates in the 12th century. This difference is expressed in the sources in which the pagan Slavs always barbarians are called, while this is in the pagan Scandinavians not always the case, but they often dani , Norman or suenes hot. The political goal of expanding power only gradually gained acceptance among the military campaigns. For a long time, the warriors 'pure lust for baggage and the leaders' political goals were intertwined, which is why the assignment of a campaign to "Viking campaigns" or "wars of conquest" is extremely problematic. This development finds its literary expression in the fact that in the royal sagas the ruling kings are never called "Vikings", despite all warlike endeavors, which of course were associated with booty. In connection with Harald Blauzahn , it is reported that his nephew Gullharald, since he did not become king, instead became a "Viking". Here, therefore, only the pretender to the throne who does not come into play is referred to as a "Viking" who earns his living through raids.

Delimitation problems

When describing the activities, it should be noted that there are no delimitations. The attack on Scottish monasteries at the beginning of the Viking Age and the regular war expeditions to England, in which one must rather speak of invasions, or the battles for Dublin are fundamentally different. The transitions are fluid. Ascribing one company to the Vikings, but to designate the other as such by the Norsemen, can lead to an arbitrary separation of historically related things. Because what began as a Viking attack can later turn into a regular invasion or a regular war campaign with looting as an accompaniment by the same teams under new leadership. Benjamin Scheller differentiates between three phases: He starts the first phase with the attack on the Lindisfarne monastery in 793. The raids were limited to the summer months, and the Vikings returned home afterwards. He sets the beginning of the second phase at 843. Since that year, the Vikings have not returned, but wintered on site. The groups formed larger associations under unified leadership and came not only by sea, but also by land and also up the rivers. He dates the beginning of the final phase to 876, when there was a Viking immigration in England, which led to the conquest of land and the division of the land among the followers.

In addition, a distinction must be made between punctual raids and the regular and larger-scale raids. Einhard's life of Charlemagne is a typical example:

"Ultimum contra Normannos, qui Dani vocantur, primo pyraticam exercentes, deinde maiori classe litora Galliae atque Germaniae vastantes, bellum susceptum est. Quorum rex Godofridus adeo vana spe inflatus erat, ut sibi totius Germaniae promitteret potestatem. "

“The last war that was waged against the Normans, who are called Danes, first carried out piracy, then devastated the coast of Gaul and Germania with a larger fleet. Your King Gudfred was puffed up with such vain hope that he promised himself rule over all of Germania. "

Here, in the “first - then” time scheme, a clear distinction is made between robbery and large-scale raids and then the spatial conquest by the king is addressed. In any case, it is nowhere to be found in the sources that the winter bases in Franconia or England were seen as precursors to a land grab.

A change in objectives can only be observed in England when the Danelag was established in 875/876 and the Normans began to settle regularly. For the Franconian Empire, the enfeoffment of roller blinds should be mentioned here. But the Viking raids did not end there, rather the settlement activity increased very gradually and the private raids also gradually decreased. Therefore, the activities of the Norsemen in the Viking Age are presented in the article Viking Age without differentiating between Vikings in the narrower sense and Norsemen . The theories about the reasons for this development can also be found there.

Relationship between robbery and civil acquisition

From the silver deposits it is not possible to identify which share is due to robbery or ransom and which is due to trade, even if these activities are terminologically separated in the sources. This is what the Egil saga says about the navigator Björn:

"Björn var farmaðr mikill, var stundum í víking, en stundum í kaupferðum ..."

"Björn was a great seafarer and was at times on a Viking trip and at times on a trade trip ..."

And about Þorir klakka in the Heimskringla:

"Maðr er nefndr Þórir klakka, vin mikill Hákonar jarls, ok var longum í víking, en stundum í kaupferðum ..."

"One man's name was Þorir klakka, a great friend of Jarl Håkon, had been a Viking for a long time, at times also traveled as a merchant ..."

Björn, the son of Harald Hårfagres, king of Vestfold expressly emphasizes that he seldom went to war, but rather maintained trade connections from Tønsberg to Vik nearby, to the countries in the far north, to Denmark and the Sachsenland, and therefore maintained the Was nicknamed "seafarer" or "merchant". A distinction is made here between the terms of trade and viking.

The traditional trade routes were used in the Viking Age. Regis Boyer describes them as defensive merchants who, depending on the situation, decided to plunder instead of bargaining. Everything was traded: food (dried meat and fish), cloth, hides, wood, ivory, jewelry, weapons and, above all, slaves . Slaves, d. H. Unfree, determined the social structures of Nordic society.

The rich hacked silver finds in England described below confirm that the stolen goods, especially slaves, were traded. Ansgar meets Christian slaves in Birka .

From the runic inscriptions about the journeys of the dead during their lifetime and about the experiences of those returning home, only limited conclusions can be drawn about the relationship between robbery journeys and trade journeys. Since the rune stones of the end of the Viking Age are memorial stones, they mostly refer to the dead. The trader, who noticed the wealth of a monastery, was able to visit the same monastery as a member of a raid the following year. The pirate could sell the stolen goods, for example slaves, as goods in a market. It cannot be assumed at all that all Vikings behaved in the same way everywhere. This also applies to members of pure robber gangs.

There is much to suggest that the stone that was found in Rösås ( Kronobergs län ) was erected for a Christian merchant in England at the beginning of the 11th century, as the burial site of Bath is far outside the Scandinavian settlement area. That speaks in favor of a separation between Vikings and traders, as this man cannot then be considered a Viking.

Rimbert describes the invasion of the Swedes in Courland around 852. There, in addition to the fighters, negotiatiores (traders) are mentioned in the army and clearly differentiated from those who propose to ask Christ for help with an oracle during the unsuccessful siege of Grobiņa .

A behavior that was probably typical of that time is portrayed in the story of Olav the Saint. Þórir hundur , Karli and his brother Gunsteinn go on víking to Bjarmaland:

"En er þeir komu til Bjarmalands þá lögðu þeir til kaupstaðar. Tókst þar kaupstefna. Fengu þeir menn allir fullræði fjár er fé Höfðu til að verja. Þórir fékk óf grávöru and bjór and safala. Karli hafði og allemikið fé það er hann keypti skinnavöru marga. En er þar var lokið kaupstefnu þá héldu þeir út eftir ánni Vínu. Var þá sundur says friði við landsmenn. En er þeir koma til hafs út þá eiga þeir skiparastefnu. Spyr Þórir ef mönnum sé nokkur hugur á að ganga upp á land og fá sér fjár. Menn svöruðu að þess voru fúsir ef féföng lægju brýn við. Þórir segir að fé mundi fást ef ferð sú tækist vel 'en eigi óvænt að mannhætta gerist í förinni.' Allir sögðu að til vildu ráða ef fjárvon væri. "

“When they came to Bjarmaland, they anchored at a trading post and there was a market there, and those who could pay abundantly bought goods there in abundance. Þórir bought a lot of gray work as well as beaver pelts and sable pelts . Karli also had plenty of money, from which he bought a lot of fur. When the market was now closed, they sailed down the Dwina River, and thereupon the peace with the rural population was declared over. When they got out to sea, the two armies held a conference about it, and órir asked if the men were all disposed to go ashore and get booty there. The men replied that they would be very happy to do so when certain prey was in prospect. Þórir said that if their train ends well, they will certainly make loot there, but it is not unlikely that human lives will have to be put at risk on the journey. Everyone declared that they wanted to dare to take the train if they could hope for booty. "

At least for the time of Olav the Holy, Snorri and his readers took it for granted that the same voyage was traded and robbed, yes, a ritual for the change is even hinted at, in which the peace is especially “canceled”. You can also see the special motivation from expected prey. If no prey was to be expected, military ventures were avoided.

“Þar var skammt á land upp jarl sá, er Arnfinnur er nefndur; en er hann spurði, að víkingar voru þar komnir við land, þá sendi hann menn sína á fund þeirra þess erindis að vita, hvort þeir vildu þar friðland hafa eða hernað. En er sendimenn voru komnir á fund Þórólfs með sín erindi, þá sagði hann, að þeir myndu þar ekki herja, sagði, að þeim var engi nauðsyn til að herja þar og fara au varkildi, sagðarugt, a eð "

“A Jarl named Arnfin lived a little inland. When he heard that Vikings had come into the country, he sent his men to meet them with orders to find out whether they were coming in peace or in enmity. Since the ambassadors came to Thorolf with their message, he said they would not be here. He said that they felt no need to armies there and to act in a warlike manner. The country is not rich. "

This inextricable interlinking of robbery and civilian acquisition is particularly evident in the term felagi (plural felagaR ), which means “comrade”. FelagaR were men who pooled parts of their movable assets, which from then on served a joint company. They shared profit and risk. But also comrades on a common campaign were felagaR. The nature of the ventures is controversial. Finnur Jónsson advocated the view that it was purely a trade trip, while Magnus Olsen thought the Felagi were comrades on the war expedition. The authors of the Danske Runeinnskrifter assume for the Danish rune stones exclusively the martial meaning. It should be noted that in the early days of the robbery trade there was not a strict separation between these activities everywhere.

This does not apply to the Vikings, who ravaged the Franconian Empire and England in the 9th century. Men who lived in fortified camps for several years and roamed the country burning and murdering were not farmers and had no knowledge of the trade. It was a completely different social group with its own laws and norms of action. Others participated in one or the other company, but most of them are unlikely to have participated at all.

trade

Contract loyalty

In the Franconian and Anglo-Saxon sources, contractual loyalty is assessed differently. Since contracts were personal, it certainly depended on the character and attitude of the people who signed the contract. In addition, it must be taken into account that contract loyalty does not necessarily have to be ethically motivated. You do not conclude any further contracts with people who do not keep contracts. If tribute payments were repeatedly made to Vikings in order to prevent them from attacking, the contractual partners paying tribute must have made the experience that afterwards the attacks usually did not take place. In addition, it must be taken into account that at that time contracts were only valid between the people who concluded them and beyond that were not effective. This is also known from the continental vassal contracts, which were only valid during the lifetime of both partners and ended with the death of the master (master case) or the vassal (male case). This was a general principle for the Vikings as well.

"Anno Domini incarnationis DCCCLXXXIIII. Nortmanni, qui ab Haslon recesserant, Somnam fluvium intrant ibique consederunt. Quorum creberrimas incursiones cum Carlomannus sustinere non posset, pecuniam pollicetur, si a regno eius recederent. Mox avidae gentis animi ad optinendam pecuniam exardescunt et XII milia pondera argenti puri atque probati exigunt totidemque annis pacem promittunt. Accepta tam ingenti pecunia funes a litore solvunt, naves concendunt et marina litora repetunt. … Nortmanni cognita morte regis protinus in regnum revertuntur. Itaque Hugo abba et ceteri proceres legatos ad eos dirigunt, promissionem et fidem datam violatam esse proclamant. Ad hac illi respondent, se cum Carlomanno rege, non cum alio aliquo foedus pepigisse; quisquis seine esset, qui ei in regnum succederet, eiusdem numeri et quantitatis pecuniam daret, si quiete ac pacifice imperium tenere vellet. "

“In the year of the divine Incarnation, 884, the Normans, who had withdrawn from Asselt, entered the Somme and settled there. Since Karlmann could not withstand their frequent incursions, he promises them money when they leave his empire. Soon the hearts of this greedy people burn after receiving the money, they raise 12,000 pounds of pure and refined silver and promise peace for as many years. After receiving such a tremendous sum, they loosen the ropes from the bank, board their ships, and hurry back to the seaside. … [Karlmann dies in the same year]… The Normans return to the empire immediately when they hear about the death of the king. The abbot Hugo and the other greats therefore send envoys to them and reproach them for violating their promise and the commitment they have entered into. To this they replied that they had made a treaty with King Karlmann and not with anyone else; Whoever wants to be who succeeds him in government, he must give a sum of money of the same amount and weight if he wants to own his kingdom in peace and quiet. "

While the sources overwhelmingly state that the Vikings kept their part of the bargain after receiving the ransom and withdrew, it is said now and then that they did not take it seriously when it came to adherence to the contract. When they were besieged by King Charles in Angers and were in serious danger of losing their ships, they offered ransom for free departure.

"Rex turpi cupiditate superatus pecuniam recepit et ab obsidione recedens hostibus vias patefecit. Illi conscensis navibus in Ligerim revertuntur et nequaquam, ut spoponderant, ex regno eius recesserunt; sed in eodem loco manentes multo peiora et inmaniora, quam antea facerant, perpetrarunt. "

“Overcome by despicable greed, the King [Charles the Bald] accepted the money, lifted the siege and gave the enemy the road. They board their ships and return to the Loire, but by no means leave his kingdom as they had vowed, but remaining in the same area they committed far worse and more inhumane things than they had done before. "

The monk of St. Vaast describes the behavior of the Normans during the siege of Meaux as a blatant breach of contract :

"Interim Nortmanni Meldis civitatem obsidione vallant, machinas instruct, aggerem comportant ad capiendam urbem. … Cumque hi qui infra civitatem erant inclusi, obsidione pertesi, fame attenuati, mortibus etiam suorum nimis afflicti, cernerent ex nulla parte sibi auxilium adfuturum, cum Normannis sibi notos agere coeperunt, ut data civitate vivi sinerentur abire. Quid plura? Refertur ad multitudinem, et sub spetie pacis obsidens dant. Reserantur portae, fit via Christianis, ut egrediantur, delegatis his qui eos quo vellent ducerent. Cumque amnem Maternam transissent et longius a civitate processissent, Nortmanni eos omnes insecuti comprehenderunt ipsum episcopum cum omni populo. "

“Meanwhile the Normans besieged the city of Meaux, set up siege engines and built a dam to conquer the city. ... And when those trapped in the city, exhausted by the siege, exhausted by hunger and very saddened by the death of theirs, saw that help would not come from either side, they began to negotiate with Normans they knew that they could safely withdraw their lives after the city was handed over. What further: the proposal was communicated to the crowd and given by the Normans as a pretense hostage. The city gates were opened, the way cleared for Christians, and people appointed to take them where they wanted. But after they had crossed the Marne and had already moved further from the city, the Normans all set out to pursue them and made the bishop prisoner with all the people. "

In the Anglo-Saxon sources, the descriptions of breaches of contract predominate. In 876, after lengthy battles, a settlement was reached in which the Vikings swore to leave Northumberland . They swore the oath both according to pagan custom on the holy armring and according to Christian custom on the relics. But the oath was not kept, and in the same year Halfdan established himself in Northumberland so that he could divide the empire among his own.

The end

The end of the raids does not coincide with the end of the period known as the Viking Age (1066 with the Battle of Hastings ). Because the private raids had already come to an end before then. The dating of the end is related to the fact that one includes the raids of Norwegian kings in the course of their wars, which even took place under Magnus Berrføtt (1073-1103), which is why he has been called the last Viking king . This looting was the common way of funding a war across Europe at the time and is not something specific to Vikings.

The settlements and land allocations described below in no way led to an end to the raids. The murderous gangs turned into non-peaceful peasants and family fathers. The sources report bloody fighting even after the land grants. Rather, a general exhaustion of the Vikings involved and an aging of the participants is more likely. The age of entry into a following is set at 18 years. Warrior life ended at the age of 50. According to the sources, the same groups were on the move for many years. The losses in the fighting could gradually no longer be replenished from the original homeland, as the negative assessment of the pillaging pillage there became more and more prevalent in the course of the strengthening of the royal power. Added to this was the gradually strengthening defense in the affected areas, which made the previously more or less safe raids more and more an incalculable risk. The transition to civilized behavior according to the standards of the time is due on the one hand to the biological generation change and on the other hand to the women, who were largely recruited from the local population and therefore conveyed their culture to the following generation, while the marauding Viking gangs did not have their own Culture that they could have passed on.

The increasing fortification of the areas to be plundered, which went hand in hand with the professionalization of the defending armies, is also likely to be an essential factor. The victims of the raids quickly developed strategies to counter the Vikings. Cities were provided with fortifications, while castles were built in strategically important places , to which the people could take refuge in case of danger. Vikings were generally unable to overcome such defenses, while the garrison of these fortifications posed a constant threat to raiding forces.

England

In England, the raids began to end with the first settlements in Northumbria in 876 and were essentially completed by 918. This means that the end was already in sight when the Christianization of Scandinavia had not yet established itself, so that this process cannot be used as a cause.

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle reports for England:

“& Þy geare Healfdene Norþanhymbra lond gedælde. & ergende wæron & hiera tilgende. "

"... and Halfdan divided up the Northumbrian land, and from then on they began to plow and support themselves."

And Asser writes:

"Eodem quoque anno Halfdene, rex illius partis Northanhymbrorum, totam regionem sibimet et suis divisit, et illam cum suo exercitu coluit."

"That year Halfdan, the king of this part of Northumbria, divided the whole region between himself and his own and built it up with his army."

Those involved from the exercitus (army) were still warriors, not farmers. Sedentariness was the result of previous violence, not its goal. In a further stage, Viking groups in 877 and 880 settled in Mercia and East Anglia under the leadership of Guthrum . Æthelweard writes that all the inhabitants of this country were brought sub iugo imperii sui (under the yoke of his rule). Here, too, violence was evidently the order of the day. A part of his contingent moved in 880 to further looting campaigns in France. In 893 they came back to England with 250 ships. In 897 the contingent split again after heavy fighting, and one part went to the Danes in Northumbria and East Anglia , the other back to France. Gradually the Viking robbery group broke up. From the overall view of the sources, Zettel deduces that the reason for this development is to be found in the increasing resistance of the English aristocracy on the one hand and the increasing exhaustion of the Norman fighting resources on the other. In 875 she had defeated Alfred at Ashdown. In 877 the Vikings lost 120 ships in a storm. She then pursued Alfred on land, which then led to the branch in Mercia. Such a bloodletting could not be compensated for soon. But the fierce fighting accompanying the entire process shows that marauding following groups still existed here. The integration process is estimated at around 100 years, i.e. at least three generations. After Alfred's victory over Guthrum 878, a contractual settlement was made.

In the period that followed, Alfred covered the area he ruled with fortified squares, professionalized his domestic troops by creating a standing army for the first time and setting up a navy. In the later Viking attacks, the fortifications in particular proved to be very successful, as they not only served as a deployment point for possible counterattacks, but also as a safe haven for people and capital in the form of cattle, gold, etc. Raids became less and less profitable and increasingly risky. In the Burghal Hidage 33 fortified places are named, the occupation of which was financed by specially released land. These enormous expenditures indicate, on the one hand, that the Viking threat persisted and, on the other hand, that these fortresses were doing their job as expected.

This tactic was continued by his son Eduard the Elder , his daughter Ethelfleda and later his grandson Æthelstan , who pushed Northmen settling in England further and further back through a combination of fortifications and open field battles, until under Æthelstan the whole of England was pushed back through the Saxons for the first time was mastered.

France

In 897 those Danes who had no money moved back to France by ship. Apparently they could only settle down with their tribal members for money.

In 896 5 Norman ships came into the Seine. Other ships were added and these sailed into the Oise and settled in Choisy . In 897 they made a raid as far as the Meuse . Fearing the royal army that would appear, they moved to the Seine and carried out further raids there. Their leader Hundus was baptized in 897 and then disappears from the sources. Instead, Rollo now appears. This suffered several heavy defeats in the following period against the increasingly determined defense of the Franks under Count Robert and Duke Richard , which he could no longer adequately compensate. In the sources, the connection between these losses and the willingness to Christianize is described again and again. There was an acute danger of complete annihilation. Rollo did not come from the north as the founder of the state, but he and the rest of his team, who were left over from the already decimated part of the Normans who had come from England in 896, were assigned a limited area as residence per tutela regni (for Protection of the kingdom) The conversion to Christianity is seen as a means to appease the lust for murder and a condition of the allocation of land. There is no reference in the sources for a plan to establish an own rule in Normandy, i.e. for a war of conquest by the Normans. In general, the lengthy process of integration in Normandy will be completed around the year 1000. It played a special role that the Normans were drawn into the inner Franconian disputes as early as 920. But for the first two decades after the conclusion of the contract, the raids still predominate. They took place in Brittany , Aquitaine , Auvergne and Burgundy . The choice of words depraedari , vastare and pyratae in Flodoard and in other sources shows no difference to the time before. As before, high tributes are being extorted for peace. What is new here is the demand for land, which in 924 led to the surrender of further areas, including Bayeux . Under Rollos' son, Wilhelm, there were still raids. The raids on the areas of the Rhine and Waal estuaries in 1006 and 1007 were only sporadic raids in the style of the Vikings, but not comparable to the great raids of the past.

equipment

The most important things for the Vikings were the ships and the weapons.

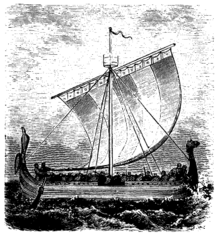

Ships and crew

For the Vikings of the Sagas, the types of ships are fairly well known. The warships were usually longships of different sizes. It is unlikely that the Vikings carried horses on their raids on these ships. Nothing is reported on this in the sources. In view of the row benches at a distance of 70–100 cm and the equipment to be stowed, this would have been rather difficult, especially since water and feed would have had to be carried. As far as horses were used, they must have been requisitioned on site. Asser reports that the Normans brought their horses from France to the siege of Rochester in 884. In addition, he and the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle report (for the year 866) that the horses were requisitioned on site. It is not known whether the Vikings fought on horseback themselves. But the fight on horseback was well known.