History of the Swiss Railway

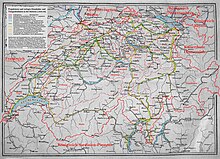

The history of Swiss railways was up to the opening of the first stretch (of Strasbourg ) to Basel in 1844 once a history of planning: Since the 1820s worked the then sovereign cantons and private Industrial advanced projects, but due to the political instability could not be implemented during the restoration and the conflicting interests of the cantons. The first railway line built exclusively on Swiss soil was opened in 1847 between Zurich and Baden . A real boom in railway construction only began with the passage of the Railway Act in 1852. It stipulated that railways should be built and operated by private companies or cantons, which led to bitter competition between the various private railway companies and the bankruptcy of the Swiss East-West Railway in 1861 and the Swiss National Railway in 1878. This was one of the reasons that led to a change of opinion and led to the demand for the nationalization of the railway companies. This happened between 1901 and 1909, when the five large private railways were transferred to the Swiss Federal Railways . Private railways continued to be founded; however, these were not in the hands of private owners, but mostly in municipal or state hands. Due to the lack of coal in Switzerland, the electrification of the routes, which was promoted by the two world wars, began early on. After the Second World War , the competition from road traffic increased, so that some routes were closed; but not to the same extent as in the rest of Europe.

It was not until 1975 that the Heitersberg line, the first new line since the Second World War, was inaugurated. The introduction of the regular timetable in 1982 was another milestone in the organization of the Swiss railway system, which was promoted by the Zurich S-Bahn and the development of other S-Bahn networks. With the opening of the new Mattstetten – Rothrist line in 2004, the core of the Bahn 2000 concept was completed. With the Lötschberg base tunnel and the Gotthard base tunnel , both tunnels of the new rail link through the Alps have now been completed. The medium-term expansion measures are summarized in the Future Development of Railway Infrastructure project .

prehistory

Although Switzerland as a European country began building railway lines late, the general road network was well developed early on. During the “magical 1830s” steamboats operated on the lakes and alpine passes on the Splügen and Gotthard were expanded. The quality of the roads varied from municipality to municipality and pebbles or natural asphalt from the canton of Neuchâtel were used as the road surface .

After the end of the Helvetic Republic in 1803, the postal system was no longer subject to the cantons . Many private entrepreneurs therefore offered passenger transport services. In the 1820s there were several express car services between Zurich and Chur, as well as between Geneva via Lausanne to Friborg and from Bern to Zurich. When the pass roads were further expanded between 1827 and 1831, a travel report describes the journey from Altdorf to Bellinzona , which took around 15 hours. Travel times from north to south were shortened even more when the first steamship operated between Lucerne and Flüelen in 1839. The advertising posters in the passenger transport business, which are still famous today, were created for the first time in 1844: The Altdorf post office advertised the “daily express car course”, which is the fastest and most convenient connection between Italy and southern Germany ; the journey from Lucerne to Milan took around 31 hours.

Pioneering time

Around the middle of the 19th century, Swiss merchants and newspapers reported more and more of journeys with the new means of transport, the railroad, the construction of which had already progressed in the surrounding countries such as Germany and Austria . Merchants realized that the railroad had low transport costs, which in turn would result in lower prices for goods. Associated with this, however, were the fears of local industries and agriculture that the construction of a railroad would inundate them with cheaper competing products from other parts of Europe, which in turn mobilized resistance to rail projects. The first railway line on Swiss soil ran from St. Louis to Basel . It was the southernmost part of the Strasbourg – Basel railway , built and operated by the Compagnie de Strasbourg à Bâle under the direction of Nicolas Koechlin . The line opened on June 15, 1844, but the French station in Basel was not completed as a permanent station until December 11, 1845.

The Zurich Chamber of Commerce suggested the first ideas for building an inland railway line in 1836: A railway line between Zurich and Basel along the Limmat , the Aare and the Rhine . But after the two half-cantons of Baselland and Basel-Stadt had rejected the construction, the Zurich merchants decided to change the route to Zurich - Baden - Koblenz - Waldshut in order to be able to guarantee a connection to the German Baden main line . However, since there was not enough money for the whole route, only the route between Zurich and Baden in the canton of Aargau could be opened. It is considered the first Swiss railway line and was operated by the Swiss Northern Railway. It measured 23 kilometers and got its nickname from a Baden specialty, the Spanish bread rolls , a yeast pastry. The inauguration of the “Spanish-Brötli-Bahn” was festively celebrated on August 7, 1847 and aroused hope from technical progress.

At that time there were already many plans and often competing projects for further rail connections. In 1846, even before the state was founded , a conference of ten so-called railway committees approved the construction of a Swiss-wide route between Lake Constance and Lake Geneva . The new federal constitution of 1848 then created the political and economic prerequisites for the creation of a route network, although the railways were not expressly mentioned in it. The Railway Act of 1852 then ended the discussions about a federal state railway system by opting for private railway companies under the supervision of the cantons .

In 1857, a rail mail car was used for the first time in Switzerland on the Swiss Northeast Railway on the Zurich – Baden – Brugg route. This was the beginning of the Swiss rail mail .

The Railway Act of 1852

During the regeneration period , all cross-cantonal railway projects, with the exception of the Zurich-Baden line of the Swiss Northern Railway, failed due to the political fragmentation of Switzerland ( confederation ) and the conflicting interests of the cantons. That only changed with the adoption of the Swiss Federal Constitution of 1848, which created a central political authority ( federal state ) on the territory of Switzerland and thus indirectly created the institutional prerequisite for enacting railway legislation binding for all cantons at the federal level. As early as September 1849, a group of 14 national councilors initiated the legislative process for a nationwide railway law with a motion to the Federal Council .

The initiators had different motives, which can be summarized in three groups. First of all, the fear was voiced in broad circles of the political public that without railroads Switzerland would "miss out on the times" and, due to the brisk railway construction activity abroad, in the near future it would be off the main European traffic axes, which would result in a loss of customs revenues and transport (Switzerland at that time had a well-developed network of rural roads). Second, merchants and tradespeople hoped that the railways would provide an economic upswing by making transportation cheaper and faster. A third, decisive reason was the property of the railroad as an investment object , which promised satisfactory returns in a time of cheap money capital.

The legislative process initiated in 1849 extended over two and a half years due to the extensive preliminary clarifications regarding the route, financing options and influence on Swiss industry as well as due to the multiple postponements of the decision by the advisory railway commission . Which was 1849 State Railways during the still vibrant national unification movement by the majority of MPs and newspapers euphorically as "big Nationalbau" advocated the idea of the state railway lost during the two and a half years of the legislative process gradually ground. When, on July 8, 1852, the National Council had to decide on the two competing draft bills of the Railway Commission - state railway and private railway - 69 councils voted for the construction and operation of the railway by private individuals and 22 for construction and operation by the federal government . On July 28, 1852, the Council of States confirmed the National Council 's decision, whereby the “Federal Law on the Construction and Operation of Railways in the Confederation” came into force. The construction of the railway in Switzerland was thus left to private companies , although the cantons had to award the concessions and the railway projects had to be approved by the federal government. The supervisory function of the cantons and the federal government should ensure that the military interests of Switzerland were protected in the routing, that the lines were built to be technically compatible and that the connections were guaranteed.

The decision of the Swiss parliament in favor of the private construction and operation of the railways refers to the complex and changing interests of the cantons and political groups between 1849 and 1852. Two reasons can ultimately be given for the failure of the state railroad idea:

1. The enthusiasm for the new central political power in Switzerland that still prevailed in 1848 gave way to disillusionment in the following years, caused by the conflicting legislation in the postal, customs and especially in the coinage as well as in the order of weight and measure, which naturally not all regional Could consider interests equally. This led to an increasingly anti-centralist stance across all political camps , particularly in western Switzerland . On the railroad issue, most of the French-speaking Swiss, but also anti-centralist German-speaking Swiss parliamentarians, feared a further expansion of federal activity ( centralism ) and thus a curtailment of cantonal competencies as a result of the construction of the state railways , and the majority therefore voted for the private railroad. This fear was heightened by the uncertain profitability of the planned nationwide railway network, which in the event of a deficit could have induced the federal government to raise further taxes. Some even believed that the stress from the railroad network could destabilize the financially unconsolidated state.

2. Due to the high construction costs of the railway network, the draft laws drawn up by the Federal Council and the Commission could not take into account the wishes of all the cantons in the routing. In addition, to minimize the financial risk, the railway network should be built in stages, which would have delayed construction in some regions for years. This “artificial shortage of the railroad resource” fueled the canton's conflict of interests, which the Federal Council was unable to defuse, partly due to a lack of expertise in railway matters, partly due to a lack of awareness of the acute conflict potential of these conflicting interests. This ultimately led to the fact that many parliamentarians from the empty cantons as well as the parliamentarians of those cantons who wanted to build railways quickly due to high profitability expectations in their regions or who basically preferred a route deviating from the draft law, a majority voted for private construction.

First private railway wave

The leading companies were the Basler Schweizerische Centralbahn- Gesellschaft and the Schweizerische Nordostbahn (NOB), founded in 1853 as the successor to the Schweizerische Nordbahn . On December 19, 1854, the Centralbahn opened its first section from Basel to Liestal and in the following years the shortcomings of the past few years were quickly made up for: the north-east line of the Zurich “railway king ” Alfred Escher opened the Oerlikon – Winterthur – Romanshorn line , the Compagnie de l 'Ouest Suisse , the oldest predecessor of what would later become the great Jura-Simplon Railway , began operating on the Yverdon – Morges section and the Wil – Winterthur line of the Sankt Gallisch-Appenzellische Eisenbahn laid the foundation for the future network of the United Swiss Railways placed. Five years later, the route network was already more than 1000 km long, there was a continuous connection via Zurich - Olten - Herzogenbuchsee - Solothurn - Neuchâtel - Lausanne from Lake Constance to Geneva , to which also Bern , Lucerne , Chur , St. Gallen , Schaffhausen and Basel were connected.

In 1857 the St. Gallisch-Appenzell Railway, the Swiss Southeast Railway and the Glatthal Railway merged to form the United Swiss Railway . The Sankt Gallisch-Appenzell Railway Company was founded in 1852 by Karl von Etzel and included the line from Winterthur to the Rorschacher Hafen.

The Südostbahn consisted of the Rhine Valley line from Rorschach station via Sargans to Chur and the Linth Line of Rapperswil -Sargans and the Glarner line Weesen - Glarus . The Rorschach – Chur line was to be the first section of a railway from Lake Constance over the Lukmanier Pass to Lake Maggiore and the Sargans – Rapperswil line was to be the second access line over the Lukmanier Railway, which was never built, in the direction of Zurich and Basel. These efforts go back to the year 1839 and were mainly inspired by the engineer Richard La Nicca . The third line, the Glatthalbahn, comprised the line from Uster to Wallisellen , to which the line from Uster to Rapperswil was later added.

For many years there was heated argument about the right way to cross the Alps , which had been planned for a long time . Only after Austria ( Semmering 1854, Brenner 1867) and France with Italy ( Mont Cenis 1871) opened their Alpine railways, a decision was made in Switzerland, and in 1882 the Gotthard Railway was able to start operating after the 15 km long top tunnel was completed .

The network of private railway companies throughout Switzerland had continued to grow and the weaknesses of this system had become increasingly evident. In western Switzerland in particular , bankruptcies, mergers and new foundations of the railways, which were set up solely for profit, were almost the order of the day; the semi-public Jura-Simplon Railway , which was finally founded in 1890, had around 20 predecessor companies in 35 years. The Swiss National Railway, founded in 1870 by the democrats in Winterthur to compete with the existing companies, was also out of luck. The aim was to build a railway from Lake Constance to Lake Geneva , which should break the monopoly of the existing railway companies Nordostbahn (NOB), Schweizerische Centralbahn (SCB) and Chemins de fer de la Suisse Occidentale (SO). However, the new company had to be liquidated in 1878. Villages and towns along the route were deeply in debt and often had to pay off the debts caused by the Swiss National Railways well into the 20th century . The cities of Winterthur , Baden , Lenzburg and Zofingen had particularly high debts . Winterthur did not pay the last national railway debts until 1954. The increasing influence of foreign capital also gave the state railway idea new impetus.

Nationalization and establishment of the Swiss Federal Railways SBB

In a first step, in 1872, railway sovereignty (e.g. granting a concession) was transferred from the cantons to the federal government. Because the competition between various private railway companies initially hindered a coordinated overall development.

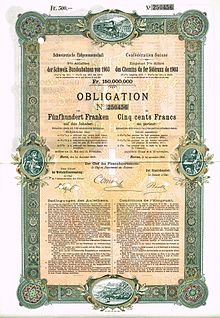

On February 20, 1898, the Swiss people were called to the polls to vote on the nationalization of the Swiss railways. Both opponents and supporters had campaigned for the cause in advance, and the opponents had put forward solid arguments. The group of opponents consisted mainly of the private operators of the individual railways, their shareholders and the capital-investing banks. The outcome of the vote was completely open. The people approved the state railway project with 386,634 yes to 182,716 no. From the perspective of the sovereign, the Swiss railways should belong to him, the Swiss people.

After the referendum of February 20, 1898 (federal law on the acquisition and operation of railways for the account of the federal government and the organization of the administration of the Swiss Federal Railways), the newly founded Swiss Federal Railways (SBB) initially took over the four large companies SCB from 1902, NOB, VSB and JS as well as some smaller Swiss private railways . In 1909 the Gotthard Railway Company was also nationalized. Initially there were five district offices, from which the three SBB district offices in Lausanne, Lucerne and Zurich emerged in 1923. The former Centralbahnverwaltung Basel was attached to the headquarters in Lucerne , the previous St. Gallen district of the Zurich district directorate .

Finally, the following private railways were incorporated into SBB:

- Swiss Central Railway (SCB)

- Swiss Northeast Railway (NOB) including the Lake Constance fleet

- United Swiss Railways (VSB)

- Jura-Simplon Railway (JS) including Brünig Railway (from 1903)

- Gotthard Railway Company (GB) (from 1909)

- Jura neuchâtelois (JN) (from 1913)

- Tösstalbahn (TTB) including Wald-Rüti-Bahn (from 1918)

- Seetalbahn (STB) (from 1922)

- Uerikon-Bauma-Bahn (UeBB) (from 1948)

The SBB network thus covered a route length of almost 2,700 km.

The owners of the numerous smaller private railways were and remained predominantly the cantons and municipalities . The long-distance network had been continuously expanded in the preceding decades and numerous branch lines were added.

The largest private railway in terms of traffic volume, the Berner Alpenbahn-Gesellschaft or Bern-Lötschberg-Simplon-Bahn (BLS) started operating in 1913 with the Lötschberg tunnel, the last major addition to the standard-gauge network for a long time.

Second private railway wave

The second wave of railway company foundations began in the 1880s and lasted into the 1920s, with the majority of these being additions to the existing route network, which go back on the initiative of municipalities and cantons and were built primarily for local development . This also includes the many narrow-gauge railways and mountain railways. Although they are referred to as private railways in Switzerland , the majority of the shares are usually in public hands.

In 1871 the Vitznau-Rigi-Bahn was the first cogwheel railway in Switzerland to go into operation and in 1889 the steepest cogwheel railway ( Pilatusbahn ) from Alpnachstad to the Pilatus was opened with inclines of 48 percent .

With the Lausanne - Cheseaux section of the Lausanne-Echallens-Bercher-Bahn (LEB) completed in 1873 , the emergence of the numerous narrow-gauge railways began. Although mostly only short branch lines , which for topographical and economic reasons could hardly have been built in standard gauge , together with the mostly narrow-gauge rack-and-pinion railways in their colorful variety they now account for almost 30% of the Swiss rail network.

However, there are also extensive networks of narrow-gauge railways in Switzerland. In a way, the Rhaetian Railway represents the state railway of the largest Swiss canton of Graubünden , as the federal railways already have their terminus in the canton capital Chur from the north. Several routes were opened between 1888 and 1922 . This opened up well-known holiday resorts such as Davos , Arosa , St. Moritz , Pontresina and Scuol . The narrow-range: the network of Rhätischen Bahn, a further line extending in the direction west Disentis - Andermatt - Gletsch the Furka-Oberalp railway (FO) in the direction of Brig and continue on the 1891 opened range of Bvz Zermatt-Bahn by Zermatt . With the completion of the Furka-Oberalp-Bahn in 1926, the construction of narrow-gauge railways in Switzerland was essentially completed.

The Rhaetian Railway opens up a further crossing over the Alps : the Albula and Bernina lines operated by it connect the central and southern European traffic areas of Germany , Austria , Switzerland and Italy on a narrow track via Chur and Tirano .

Times of war

The operation of a federally owned railway was an advantage for the active service of the Swiss Army as well as for military economic measures in the world wars. When the First World War broke out in August 1914, the still young SBB responded with a war timetable that had been drawn up in 1897. On November 11th, this was replaced by the actual war operation and the personnel were subject to military law. The railway staff opposed the stipulation that every railway worker had to guard his work area. On March 1, 1916, the Federal Council already closed the war operations. The decline in tourism and civil transport resulted in savings. Nevertheless, the deficits increased due to the rare and expensive fuel coal, which was hoarded by the warring powers for their own needs. After 1916 the timetable had to be reduced and the SBB were more dependent on their reserves for coal consumption.

In 1917 the railway workers began to revolt. Their wages could not withstand the rise in prices. When the Olten Action Committee called for a state strike in November 1918 , a large part of the railway staff joined in and carried the movement into rural areas. Rail operations were suspended from November 12th to 15th. At the same time, war operations were temporarily reintroduced. As a result of this strike, the previously loose railway workers' unions merged to form the Swiss Railway Union (SEV) in 1919 .

During the Second World War , the supply of imported coal was less of a problem thanks to an already advanced electrification; on the other hand, the infrastructure had to be protected from air strikes or the medical services of the civilian population had to be taken into account. In contrast to the First World War, rail traffic within Switzerland increased sharply after the outbreak of war because there was too little fuel for cars and trucks. Freight traffic between Germany and Italy also grew strongly. A special feature in the Second World War were special trains for the Federal Council, the two command trains for General Henri Guisan , who used them to inspect the troops, and a war press train with a built-in printer. In an emergency, it would have been used in a tunnel on the Gotthard route.

electrification

The first electric railway in Switzerland was the Tramway Vevey-Montreux-Chillon (VMC), opened in 1888 , which operated its 1000 mm route with 500 volts direct current , which existed until 1958 . In 1891 the also narrow-gauge Sissach-Gelterkinden-Bahn and the Lauterbrunnen – Mürren (BLM) mountain railway began their electrical operation, and in 1894 the 4-kilometer Chemin de fer Orbe – Chavornay (OC) was also the first standard-gauge line with direct current traction .

The first tram operated with three-phase 400 volts 40 Hertz was the Lugano tram , which opened in 1896 . The Gornergratbahn (GGB), which has been operated with three-phase current at 550 volts 40 Hertz since 1898, is the oldest electrified rack railway. The Burgdorf-Thun-Bahn (BTB), which opened in 1899 as the first full electric railway in Europe, also opted for three-phase current ; the voltage was 750 volts at 40 Hertz. Another step forward was the electrification of the Simplon Tunnel, carried out jointly with the Italian FS , in 1906 with three-phase current 3300 volts 16⅔ Hertz.

But in the year before the course had been placed in a different direction: In Zurich was headed Maschinenfabrik Oerlikon the single-phase AC test operation Seebach-Wettingen made first with 15 kV 50 Hz and then further successful trials with 15 kV 15 Hz. Two locomotives from this trial operation, which was carried out until 1909, are exhibited together with vehicles from VMC, OC and BTB in the Swiss Museum of Transport . In 1907 the Maggia Valley Railway started operating with 5000 V 20 Hz. The engines of the railcars BCFe 4/4 were operated directly with alternating current, following the example of the Seebach – Wettingen test route. In 1912, the SBB decided in favor of the current AC system with 15 kV and 16 2 ⁄ 3 Hz. The Lötschbergbahn has been operated with the same system since it opened in 1913. The Gotthard Railway was the first to be electrified as the most important route.

In the Gotthard tunnel itself, 7.5 kV was initially used because the soot from the steam locomotives still in use contaminated the insulators and, at higher voltages, led to arcing. The first electric Gotthard locomotives could be switched from 7.5 to 15 kV.

The coal shortage in the First World War prompted SBB to first electrify the Bern – Scherzligen (Thun) and Brig - Sion lines, the latter with three-phase current as a connection to the Simplon network. In 1920 the Gotthard Railway's ramp routes could be operated electrically and by 1928 more than half of the SBB routes had been electrified. This was followed by a flattening in which only gaps were closed. It was not until the Second World War that the SBB was again electrified over a large area with so-called emergency electrification, where the branch lines were also electrified with the least possible effort.

Even after the Second World War, the conversion continued and was completed in 1960 with the last two sections Cadenazzo - Luino and Niederweningen - Oberglatt . In 1967 the last steam train of the SBB ran. The SBB network is now fully wired after the short freight line Etzwilen – Singen (Hohentwiel) was shut down in 2004. The private railways are almost without exception operated electrically, although the numerous short narrow-gauge lines have remained a DC domain.

The traction electricity price system in Switzerland regulates the price that has to be paid by railway companies when they draw electricity from the contact line.

Line closures

Line closures , there were hardly any in the SBB until now. So far, the Bülach-Baden Railway , the Lenzburg - Wildegg , Solothurn - Herzogenbuchsee , Solothurn - Büren an der Aare , Beinwil am See - Beromünster (partially replaced by the Wynental and Suhrental Railway (WSB)), Aarau - Suhr (relocation the Wynental and Suhrentalbahn (WSB) on this route in November 2010), Weesen – Näfels (1918) and the route Zurich HB - Zurich Letten - Zurich Stadelhofen (replaced by the Hirschengraben tunnel ). Since December 12, 2004, the rest of the Etzwilen – Singen railway line has been closed for good due to the poor condition of the Hemishofer Rhine Bridge . Passenger traffic has been abandoned on some routes, but freight trains are still on the routes. These include the Hinwil - Bäretswil (Bäretswil - Bauma museum railway line of the DVZO ), Koblenz - Laufenburg and Wettingen - Mellingen routes .

There have been some discontinuations and route reductions in the private railways, but in comparison with other countries their scope is also quite modest. Mainly narrow-gauge branch lines were affected , which often had to give way to growing car traffic because of their course in the road, such as the Uerikon-Bauma-Bahn (1948), the Wetzikon-Meilen-Bahn (1950), the Uster-Oetwil-Bahn (1949), the Spiez connecting line (1960), the Schwyz trams between Brunnen and Schwyz (1963), the Schaffhausen – Schleitheim tram (1964), the Leuk-Leukerbad-Bahn (1967) or the Sernftalbahn to Elm GL (1969).

In the 1950s and 1960s, practically all railway lines were checked by the federal government to see whether and how they could be modernized. For some, this review was negative. This decision had the consequence that the canton's share or the share of own funds that had to be raised for the modernization rose. It should be noted here that the canton's attitude was very important as to whether a route was actually closed afterwards. In the car-friendly canton of Ticino, for example, only two railways ( Lugano-Ponte-Tresa-Bahn and Centovalli -Bahn ) were included in modernization programs and the remaining lines were closed. In the cantons that are more train-friendly, the deforestation was much less evident.

The Rhaetian Railway stopped passenger traffic on the Bellinzona – Mesocco railway in 1972 and freight traffic in 2003.

New lines / upgraded lines

In the 20th and 21st centuries, smaller and larger route extensions were carried out, as in 1916 with the opening of the new Hauenstein base tunnel on the Olten – Basel route . The Heitersberg line between Zurich - Aarau - Olten , completed in 1975, was built ahead of schedule as part of the planned New Main Transversal (NHT) . The major project for the construction of a high-speed line failed due to popular resistance. Some parts of the NHT were implemented in the Bahn 2000 project .

Further expansion of the rail network followed in 1983 with the loop at Sargans , the opening of the Zurich airport train station in 1980 (the first completely underground train station in Switzerland), the Geneva airport train station , the Born line as bypasses from Aarburg - Oftringen , Zollikofen ( gray wood tunnel ) and Pratteln ( Adlertunnel , "Bahn 2000" project). The first part of the Zimmerberg Base Tunnel was opened in 2002.

With the construction of the Zurich mountain line and the underground S-Bahn station in Zurich's main station as the core of the Zurich S-Bahn, which opened in 1990 , an important step was taken in promoting urban traffic. In addition, the Sihltalbahn and Uetlibergbahn were extended into a second, new underground part of Zurich's main train station. Most of the other S-Bahn trains in Switzerland were designed, however, only taking into account the existing routes, without new routes being built. Often only selective changes were made to the infrastructure, often in the form of additional stops. However, some lines were partially equipped with an additional track, or other performance-enhancing measures were implemented.

In addition, the following mountain routes were expanded or newly constructed: construction of the Furka base tunnel , double-track expansion of the Lötschberg mountain route and construction of the Vereina tunnel of the Rhaetian Railway (RhB).

With the protection of the Alps , for the first time, the railway received an order for the transit of international goods traffic, as laid down in the federal constitution.

In 2004, the 52 km long Mattstetten – Rothrist line was opened to traffic. The route between Zurich and Bern is driven at a speed of 200 km / h. The upgraded Solothurn – Wanzwil line branches off from the new line. In 2004 the new Salgesch – Leuk line was opened in Valais .

In 2007 the first report on the state of the Alps was published by the permanent AK secretariat: Transport and Mobility in the Alps on the Convention for the Protection of the Alps (Alpine Convention, AK). It is also based on figures from Switzerland.

At the end of 2015, the new 9.6 km long diameter line Altstetten – Zurich HB – Oerlikon went into operation. The four additional through tracks in the Löwenstrasse underground station will significantly increase the capacity of Zurich main station.

The 16.1 km long Cornavin – Eaux-Vives – Annemasse line , or CEVA for short , has been connecting the French town of Annemasse, near the border, to the Cornavin station in Geneva since 2019 .

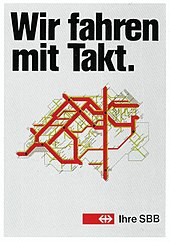

Cycle schedule

The United Bern-Worb-Bahnen (VBW) introduced Switzerland's first regular timetable on May 31, 1964 on the Worb Dorf – Worblaufen railway line . In the summer of 1968, the SBB followed on the right bank of the Zürichseebahn . The principle was to be introduced across Switzerland on all railway lines in the summer of 1977. A newspaper article "Railway timetable à la Hollandaise" in August 1973 referred to these efforts ; With hollandaise , Dutch timetables were taken as a model, since a regular timetable in the Netherlands had already connected cities with hourly trains since 1934.

Even in the 1960s, many experts were of the opinion that a nationwide regular timetable was not feasible. In March 1969, the ETH civil engineer Samuel Stähli published a 19-page report on the basic questions of timetable design, in which he recommended the introduction. The SBB timetable strategists at the time answered him with the acronym “Agabu”: Everything is very different for us.

On May 23, 1982, the clock timetable was introduced throughout Switzerland. From then on it was said: “a train every hour in each direction”. This led to a performance increase of 14% in local traffic and 31% in long-distance traffic.

Bahn 2000 and S-Bahn networks

Switzerland is not relying on the construction of new high-speed lines for the future of the railways . Instead, under the motto “Bahn 2000”, an overall concept was developed which, in addition to shortening travel times, includes further measures to improve the attractiveness. "Bahn 2000" is geared towards the goals: more frequently - faster - more direct - more convenient .

The core of the concept is the creation of a system of junction stations, between which travel times, including stops, are exactly one hour. As a result, time lost when changing trains can be significantly reduced not only in long-distance traffic , but also with connections in the region . In addition to the expansion of existing lines, some new sections are also necessary, but their total length is limited to only about 120 kilometers, which is less than 2.5% of the entire rail network. A top speed of 200 km / h is sufficient. Given the mostly relatively short travel distances, even a higher speed would not save much time.

"Bahn 2000" does not only affect SBB, but also private railways , where connections are optimized and traffic density is increased. This also requires a lot of adjustments and expansions. With the timetable change on December 12, 2004, Bahn 2000 began operations without any problems.

The following S-Bahn systems will be operated or planned in Switzerland in 2013:

- Aargau S-Bahn

- Basel S-Bahn

- Bern S-Bahn

- Chur S-Bahn

- Freiburg S-Bahn

- Léman Express

- Lucerne S-Bahn

- Schaffhausen S-Bahn

- S-Bahn St. Gallen

- S-Bahn Ticino

- Zurich S-Bahn

- Light rail train

New NEAT rail link through the Alps

The central structures of the NEAT project are the two large base tunnels through the Alps . The 38-kilometer-long, predominantly single-lane Lötschberg Base Tunnel was put into operation in 2007. In addition to the CIS and the Intercity, it can only accommodate a few freight trains every hour, at least during the day.

The 57-kilometer, double-lane Gotthard Base Tunnel is much more efficient . Passenger trains can travel at 250 km / h through the two tubes of this longest railway tunnel in the world.

In connection with the 15.4-kilometer-long Ceneri Base Tunnel between Bellinzona and Lugano, which is also under construction, the first flat line through the Alps will then be created, which nowhere has a gradient greater than 12.5 per thousand, so that all freight trains continuously without additional leader , pushing or intermediate locomotives can run. The NEAT is an important part of the relocation policy demanded by the Swiss people with the adoption of the Alpine Initiative . This stipulates that as much heavy goods traffic across the Alps as possible must be shifted from the road to the railroad.

outlook

As of 2015, Switzerland has the densest railway network in the world with 5177 kilometers on an area of 41,285 km² , apart from the city-states of Monaco and the Vatican .

Network access to the Swiss rail network has been free since March 1, 2001, initially for domestic railway companies.

The future development of the rail infrastructure is part of the dispatch passed by the Swiss Federal Council on October 17, 2007 on the “Overall FinöV”. Based on demand forecasts, ZEB plans to expand the standard gauge network, which will enable an expanded national transport offer for long-distance passenger and freight transport for the 2030 planning horizon. The development was carried out jointly between the Swiss Federal Railways and the Federal Office of Transport.

See also

- Rail transport in Switzerland

- Category: Rail transport in Switzerland

- List of SBB locomotives and railcars

- Type designations for Swiss locomotives and railcars

- Standard gauge standard car

- Narrow gauge standard car

- List of rail projects in Switzerland

- Category: Railway accidents in Switzerland

- List of railway accidents in Switzerland

- List of serious accidents involving Swiss trains abroad

- List of Swiss rail border crossings

- List of garden railways

- Swiss railway uniforms

literature

- Joseph Jung : Alfred Escher (1819–1882). The start of modern Switzerland. Part II: Northeast Railway and Swiss Railway Policy, Gotthard Project, Neue Zürcher Zeitung , Zurich 2006, ISBN 978-3-03823-236-0 .

- Joseph Jung: Alfred Escher (1819–1882). Rise, power, tragedy , NZZ Libro, Zurich 2009, ISBN 978-3-03823-522-4 .

- Hans P. Treichler , Barbara Graf, Boris Schneider, Ralph Schorno: Bahnsaga Schweiz. 150 years of Swiss railways. AS, Zurich 1996, ISBN 3-905111-07-1 .

- Peter Willen: Steam company in Switzerland. In color - from 1957. Volume 1: standard gauge. EK-Verlag, Freiburg im Breisgau 2006, ISBN 3-88255-296-4 .

- Marcus Niedt: Locomotives for Switzerland. Rarities from the archives of Swiss locomotive factories. 1899-1959. EK-Verlag, Freiburg im Breisgau 2008, ISBN 978-3-88255-302-4 .

- Ronald Gohl: The Swiss Federal Railways. History - routes - vehicles. 2nd updated edition. GeraMond, Munich 2009, ISBN 978-3-7654-7072-1 .

- Jonas Steinmann: Setting the course. The crisis on the Swiss railways and how it was overcome 1944–1982. Lang, Bern et al. 2010, ISBN 978-3-0343-0382-8 (also dissertation at the University of Bern ).

Web links

- Hans-Peter Bärtschi, Anne-Marie Dubler : Railways. In: Historical Lexicon of Switzerland .

- Swiss Federal Railways

- SBB Historical Heritage Foundation

- Discontinued railways in Switzerland

- Swiss Museum of Transport

- Alfred Escher letter edition

Individual evidence

- ↑ Really new building and not just relocating the route

- ^ Hans P. Treichler et al.: Bahnsaga Switzerland. 1996, p. 11 ff.

- ^ Hans P. Treichler et al.: Bahnsaga Switzerland. 1996, p. 14 ff.

- ^ Hans P. Treichler et al.: Bahnsaga Switzerland. 1996, p. 18 ff.

- ^ Jean-François Bergier : Naissance et croissance de la Suisse industrial (= Monographies d'Histoire Suisse. Vol. 8, ZDB -ID 414938-5 ). Francke, Bern 1974.

- ^ Official collection of the federal laws and ordinances of the Swiss Confederation. Vol. 3, 1853, ZDB -ID 216930-7 , pp. 170-176.

- ↑ Michael Koller: Progress and Self-interest. The question of sponsorship for telegraph and railway legislation in the young Swiss federal state between 1849 and 1852. ( Memento from August 4, 2012 in the web archive archive.today ) Zurich 2008.

- ^ The railway, financed with English capital, aimed to build a Lukmanier railway. It is not to be confused with today's Swiss Southeast Railway (SOB).

- ↑ Joseph Jung (ed.), Alfred Escher between Lukmanier and Gotthard. Letters on the Swiss Alpine Railway Issue 1850–1882, 3 vol., Neue Zürcher Zeitung publishing house, Zurich 2008, ISBN 978-3-03823-380-0 .

- ^ Christian Jossi: Debts paid off for seventy years. In: The Landbote . July 24, 2009, p. 11. (PDF; 242 kB)

- ^ "Railway network in Switzerland 1860" (graphic) and "Railway companies in Switzerland 1852-1866" (table), in: Joseph Jung (ed.), Alfred Eschers Briefwechsel (1852–1866). Economic liberal time window, start-ups, foreign policy. With contributions by Claudia Aufdermauer, Bruno Fischer, Joseph Jung, Björn Koch, Katrin Rigort and Sandra Wiederkehr (Alfred Escher. Letters. An Editions and Research Project of the Alfred Escher Foundation, Volume 5), Verlag Neue Zürcher Zeitung, Zurich 2013, ISBN 978-3-03823-853-9 .

- ↑ www.admin.ch: Federal law on the acquisition and operation of railways for the account of the federal government and the organization of the administration of the Swiss federal railways

- ↑ a b Hans P. Treichler u. a .: Bahnsaga Switzerland . 1996, p. 182.

- ^ Ronald Gohl: The Swiss Federal Railways. 2009, p. 39.

- ^ [Bernard Degen]: First World War, General Strike and the Consequences , in: From the value of work. Swiss trade unions - history and stories , Rotpunktverlag, Zurich 2006, ISBN 978-3-85869-323-5 , p. 135.

- ↑ Hans P. Treichler u. a .: Bahnsaga Switzerland . 1996, p. 183.

- ↑ Hans P. Treichler u. a .: Bahnsaga Switzerland . 1996, p. 184 ff.

- ↑ Discontinued railways in Switzerland

- ↑ Gisela Hürlimann: "The Railway of the Future" Modernization, automation and express transport at SBB in the context of crises and change (1965–2000); March 2006

- ^ A b Ronald Gohl: The Swiss Federal Railways. 2009, p. 110.

- ↑ 2007 First report on the state of the Alps , 2007, at alpconv.org

- ↑ rbs.ch

- ^ A b c Ronald Gohl: The Swiss Federal Railways. 2009, p. 141.

- ^ Federal Statistical Office: Infrastructure and route length. Retrieved February 28, 2020 .

- ↑ Free network access in Swiss rail traffic. In: Eisenbahn-Revue International . Issue 6, 2000, ISSN 1421-2811 , pp. 253-257.