History of the Arabic language

The history of the Arabic language deals with the development of the Semitic language Arabic . Strictly speaking, it only begins with the introduction of written records in Arabic. The earliest written document is the Koran code , which was created in the era of the third caliph Uthman ibn Affan (644–656). According to oral tradition, pre-Islamic poetry , which goes back to the 6th century, was not established until the 7th and 8th centuries. Both linguistic monuments, the Koran and poetry, formed the basis for the Arabic philologists of the 8th and 9th centuries to create a teaching system with a high degree of standardization, which made the Arabic language a language of culture and education.

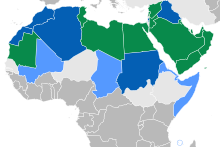

The Arabic language is the most common language of the Semitic language family and one of the six official languages of the United Nations . Today, Arabic is spoken by around 300 million people as their mother tongue or second language in 22 Arab countries and numerous other countries in Asia and Africa. As one of the six most common languages in the world and the language of Islam, Arabic is a world language. In terms of the number of native speakers, it ranks fifth.

Origin and Spread

The oldest evidence of Arabic goes back to the 9th century BC. BC back. They are proper names in Assyrian cuneiform texts . The dialectal diversity of the ancient Arabic language is well documented by inscriptions. An inscription from the year 328 AD documents the Arabic language in Nabatean-Aramaic script. Under the influence of the trading empire of the Nabateans , a standardized Arabic developed in the period between the fourth and sixth century lingua franca out.

Classical Arabic emerged as a fully developed literary language around the middle of the 6th century. Anthologies such as the Mu'allaqat contain thematically diverse poems in the Qasida form.

With the advent of Islam and the conquests of the Arabs in the 7th and 8th centuries, the Arabic language spread. It ousted Sabaean in southern Arabia, Aramaic in Syria and Iraq, Persian in Iraq, Coptic in Egypt, and the Berber dialects in North Africa and asserted itself alongside Spanish and Portuguese on the Iberian Peninsula until the end of the 15th century. The island group of Malta was Arabized from Tunisia , and from Oman, Arabic penetrated into Zanzibar and East Africa.

Today Standard Arabic is used as a written language in 22 Arab countries: from Mauritania to Iraq and from Yemen to Syria . Arabic is also spoken by minorities in Iran ( Khusistan , on the north bank of the Gulf), Afghanistan (northwest), the former Soviet Union ( Uzbekistan ), Cyprus , Turkey (southeast), Israel and Ethiopia . It is also the cultic language of all non-Arabic Islamic peoples.

- “Thus, Arabic stands before us today as a language of the greatest practical and scientific importance, a language which, despite its widespread use and rich historical past, has remained very pure and unaffected, and which has fewer foreign components than the European cultural languages. And yet it definitely reaches them in the agility of its expression. ”( Bertold Spuler : Die Spreading der Arabischen Sprache, 1954)

The Arabic within the Semitic language family

The Semitic languages are closely related to one another and a. have the following common characteristics:

- Consonant writing without designation of the short vowels (exception: Maltese )

- Throat sounds and emphatic sounds ( emphatic consonant )

- Tricycle roots

- Two grammatical genera: masculine and feminine

- Three numbers: singular, dual and plural

- Three cases: nominative, accusative and genitive

- Rectum Rain Connections

- Different types of verb action : intensive, causative, reflexive, etc.

- Late development of the concept of time in the verb (completed / unfinished)

- Frequent occurrences of the nominal sentence (sentence without copula )

- Use of paronomasia (for example: a person saying said)

- Tendency to paratax (secondary order) in sentence structure

Writing and calligraphy

- “Under the strong impression of the incorporation of foreign cultural assets into the Islamic world, one has often underestimated the importance that the Arabs themselves played in shaping them. They were not only fighters and bearers of the new religion, they also gave it language and writing. ”( Ernst Kühnel : Islamische Schriftkunst, 1942)

All letter scripts in use today ultimately go back to a Semitic consonant script. The Arabic script is the most widespread in the world after the Latin. Its scope extends from Central Asia to Central Africa and from the Far East to the Atlantic. Today, Arabic script is used to write Persian, Urdu (Pakistan and Northwest India) and the Berber languages and, until recently, the Turkic and Caucasian languages, Malay (Indonesia), Somali, Haussa and Kiswahili.

The origin of the Arabic script is not completely clear. Many theories exist about this, some of which contain fundamental contradictions. The oldest inscription is said to date from the 3rd century AD. It is believed to have emerged from the Nabatean script. The Arabic Nabataeans used Aramaic as their written language. However, the 22 letters of the Aramaic alphabet were not enough to express the 28 sounds of the Arabic language. Therefore the Arabs developed another six letters.

Typical of the Arabic script are the direction of writing, which runs from right to left, the connection between the letters and the uniformity of some letters, which can only be distinguished by the diacritical points above or below. It is a consonant script in which the short vowels can be expressed using additional characters. The introduction of the diacritical, vowel and other special characters is commonly attributed to the Arabic lexicographer al-Khalil ibn Ahmad (d. 791).

With the spread of the Arabic language as a result of Islamization, numerous writing styles emerged over the centuries. An independent art movement developed - calligraphy .

The Arabic calligraphers understood "the art of writing as the geometry of the soul, expressed through the body." This art in its codified form goes back to Ibn Muqla (886-940). The fact that the Arabic script is written along a horizontal line forms the basis for an unlimited spectrum of graphic forms that emerge on book pages as well as on walls and other surfaces. The most important fonts are briefly described below:

- a) Kufi : so named after the city of Kufa in Iraq. A geometric construction based on angular elements. This written form is the oldest. It was mainly used by Koran writers and secretaries at royal courts. The oldest surviving inscription from 692 is in the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem.

- b) Naschi : A round shape that replaced the Kufi script in the 11th century. It was mainly used to write scientific and literary works. The Koran writers also used this script.

- c) Thuluth : A complex structure that has a solemn, liturgical value. It was used for the headings of the suras in the Koran and the architectural arabesques.

- d) Ruqa : A strong, bold font with vertical lines and rounded check marks on the letter head. It was developed by the Turks.

- e) Diwani : A lively, cursive form that was also developed and cultivated by the Turks in the 15th century. Diwani was primarily the written form of the state administration and law firms.

- f) Taliq : A not too demanding form in which some letters are elongated.

- g) Nastaliq : A script developed by the Persians in the 15th century, which was used in Persia and Pakistan and the like. a. is used in the design of letters, book titles and posters. Nastaliq is a combination of Nasch and Taliq.

Until the invention of paper, the papyrus obtained from the marsh plant was considered the most important material for writing. Although it was already known to the Arabs in pre-Islamic times, it was not widely used until after the conquest of Syria and Egypt. The papyrus was particularly suitable for the correspondence of the caliphs and for administrative purposes in general, since forgery of the documents without damaging the papyrus was impossible.

The processing of papyrus into writing material was initially carried out in Egypt, later also in Iraq, where the first manufacture was founded in Samarra in 836 . Paper was already being made around the middle of the 10th century . Paper mills were built in Damascus and Basra (Iraq) that supplied the vast Islamic area with paper.

In addition to papyrus, leather, parchment, wood, palm branches, stones, textiles, ribs and shoulder blades of camels as well as pottery shards have been used for writing since pre-Islamic times. The main writing tool used was a bourdon tube pen, the handling of which was particularly important when developing a pen.

The ink was used in two ways: the simple one consisted of soot and honey, the other made of gall apples and various additives such as camphor, aloe and gum. The scribe made his own ink, taking care that it did not contain any additions of corrosive effects. Islamic calligraphers left special recipes for making ink.

Problems of writing

- "We are the only people who have to understand in order to be able to read, while all the other peoples of the earth read in order to understand." ( Anis Furaiha : An easier Arabic. 1955)

A major disadvantage of the Arabic script is probably the lack of letters for the short vowels, which, among other things, serve as carriers of grammatical functions for establishing logical connections in the sentence. A word like "mlk ملك", for example, can be interpreted differently depending on the context: malaka "own", mulk "rule", milk "property", malik "king" or malak "angel". Often enough, this homography makes it difficult to interpret the texts.

Another uncertainty factor results from the similarity of some letters differentiated only by diacritical points or their number and / or position, which often leads to confusion (see: n and b, t and th, d and dh, dsch and kh, s and sch etc.). An additional complication is the fact that the spelling of the Arabic letters, in contrast to the Latin ones, depends on their position in the word (beginning, middle, end, isolated).

Those particularities mentioned arise again in the mechanical reproduction of the writing. So z. B. In contrast to the German typewriter with only 88 types, 137 types are required for an Arabic typewriter , which is no longer important in the age of the computer. These peculiarities had an even more noticeable effect on printing, as the considerable number of printer types (700 on average) inevitably increased the printing costs. This problem is as good as no longer present.

In view of the aforementioned peculiarities of the Arabic script, the question arose whether it should not be replaced by the Latin script. Some Arab intellectuals even argue that the backwardness of the Arab world in civilization and science stems from this very writing system. However, the opposite opinion prevails among Arab scholars. You see in the Latinization of the Arabic alphabet a loss of the spirit of the Arabic language, the loss of the soul of Arabic culture, the destruction of the original grammar structures and the disappearance of calligraphy, that abstract art of Islam. So all efforts to reform the Arabic script have remained fruitless. Because the history of language teaches that a script only experiences a change or renewal when it is adopted by another language community that is unencumbered by tradition and habit. This case occurred when using the Arabic script for non-Semitic languages. For example, in Persian, Urdu and Pashto, new letters were created for the sounds that Arabic does not recognize.

Although the Arabic script is a kind of shorthand , Arabic has a shorthand ( ichtizal ). This term appears for the first time in Sulaiman al-Bustani (1856–1925). The most recent and most rational shorthand comes from André Baquni , Professor of Dactylography at the University of Damascus . He also created a shorthand based on simplified or shortened letters of the Arabic alphabet.

Language development

- "In the history of the Arabic language there is no event that had a more lasting impact on its fate than the rise of Islam." ( Johann Fück : Arabiya. 1950)

The main task of language history is to determine changes within a language and to clarify their causes. Applied to the history of the Arabic language, however, one comes under pressure, since the structure of Arabic has hardly changed noticeably since its standardization in the 9th century.

What has changed over the centuries is evidently only evident in the vocabulary, because new things and ideas require new terms that displace earlier ones and finally let them be forgotten. Words are therefore interchangeable and have only a minor influence on the structure of a language. A structural language shift only occurs when the sentence structure undergoes changes and breaks new ground. This can be ruled out for all development phases of the written Arabic language.

The history of a language is of course not limited to the language of the poets or the standard language of the educated. The history of language is not only a history of style in beautiful literature and cultivated language culture. The dialect, the spontaneous colloquial language of the various layers and groups, is also an essential part of a language. The high-level language is basically just a special form, which is often only based on a narrow sociological basis.

Therefore it must not be assumed that it represents the real language state of a time or that it is solely decisive for the development of language. However, the history of the development of the Arabic dialects is still in the dark, so that today we have to forego most of the requirements of the linguistic historical perspective.

From this it follows that the subject of the history of the Arabic language cannot consist in the exploration of the language change, but rather in the answer to a cardinal question, namely: Why was the Arabic language able to do so despite its spread in the most remote parts of the world and its contact with the various peoples That languages and cultures exert their influence, but to only be subject to insignificant external influences and thus to assert themselves as a living language up to our present day? One answer to this may lie in the following statement:

- “So far, the classical Arabiya owed its leading position largely to the fact that it served as a linguistic symbol of the cultural unity of the Islamic world in all Arab countries and far beyond. So far the force of tradition has always proven to be stronger than all attempts to displace the classical Arabiya from this dominant position. If all expectations are not deceived, it will continue to maintain this position as an Islamic cultural language in the future as long as there is an Islamic cultural unit. "

The question of why the written Arabic language has hardly changed is related to the previous question and can easily be answered on the basis of the abundance of existing evidence:

- "The rules established by the Arab national grammarians with tireless diligence and admirable devotion have presented the classical language in all its aspects phonetically, morphologically, syntactically and lexically so comprehensively that its normative grammar has reached a state of perfection that does not allow any further development."

Pre- and early Islam

Our knowledge of the state of the language of Arabic in pre-Islamic times is based on the sparse traditions of Muslim authors. Although these writings do not allow any firm conclusions, they do give an idea of that epoch through useful references. These authors were of the unanimous opinion that the Arabic language can be traced back to the dialect of the Quraish, the tribe of the Prophet, since all traces led to Mecca and the surrounding area as the birthplace of Arabic.

In fact, Mecca assumed a central position on the Arabian Peninsula by the 6th century at the latest. As the site of the sanctuary, the Kaaba, which is venerated by numerous tribes, and as an important trading center in an extensive network of intensive trade relationships, it helped the Quraish tribe to gain power and prestige. Because of this primacy, their dialect also gained in importance among other Arab tribes, although the difference between the dialects in this language region must have been slight. Constantly recurring contacts between different Arab tribes on the markets in and around Mecca, especially on the "Ukaz" market, where a lively cultural and linguistic exchange took place, favored this situation.

Until the advent of Islam, the Arabic language was dominated by poetry, which was already highly developed at the beginning of the 6th century. Her subjects ranged from the lamentations about the abandoned home of the loved one, the dangerous desert ride, the description of landscapes, animals and natural phenomena to self-praise, poems of abuse and ridicule.

In contrast, in pre-Islam prose obviously played only a minor role in cultural life. It was limited to a few animal fables, news and legends about the tribal struggles of the Arabs, to proverbs and various sayings and curses of the tribal fortune tellers, all of which were written in rhyming prose.

The linguistic and social situation in pre- and early Islam is most reliably documented in the Koran (around 650). It also reflects the economic, cultural, political and religious life of the Arabs.

The social conditions created by the new religion as well as the linguistic awareness evoked by the Koran language as a unifying force created new values that were expressed in an extensive vocabulary. From now on, the Koran was both a language regulator and a law and served as a foundation for the later standardization of the language, which has had a lasting impact on the fate of the Arabic language up to our days.

Rightly guided caliphs

After the death of the Prophet (632) and during the era of the rightly guided caliphs (632–661) the center of power remained in the holy cities of Mecca and Medina, although the Arab armies had conquered the greatest centers of civilization. The Arabs were numerically in the minority in all conquered areas. Their language was suddenly confronted with the new needs of an ever-expanding empire. It had no expressions for administration, politics, legislation and other areas that were needed in the more cosmopolitan society of the subject regions with their own linguistic and cultural traditions.

This new situation posed a serious threat to the Arabic language as the conquerors appeared to be subject to the influence of the "advanced" conquered peoples. Whether in Egypt or Syria, Iraq or Persia - the Arabs saw the need to adopt the language of the conquered for administrative purposes: Greek in Egypt and Syria, Persian in Iraq and in the eastern provinces. A linguistic conquest of the areas far from the peninsula seemed improbable, if not impossible, in view of this situation. The language of the Koran was in danger of perishing, or at least being watered down by a multilingual society. The classical Koran-Arabic has a strongly synthetic language structure , whereas Middle Greek and Middle Persian are more analytical . The Islamic expansion led to the division of Arabic into a classical written language based on the Koran , and into the lexically and grammatically very different Arabic dialects , which have an analytical language structure and are reserved exclusively for oral use. To this day, every new generation of Arabic speakers is born into this diglossia .

An important factor for the survival of the Arabic language was the traditionally strong attachment of the Arab to his language, which was now also the language of divine revelation. Language and religion were and still are one. If you wanted to understand the Koran, you had to preserve the language, or to understand the language, you had to preserve the Koran. Marriage and adoption among Arabs and non-Arabs on the one hand and their close cooperation in the leading positions of the Islamic empire on the other promoted this process. The role of the first four caliphs should not be underestimated.

The far-sighted Caliph Omar (634–644), the actual founder of the Islamic Empire, made sure that his compatriots in the conquered provinces did not perish as a minority. By stationing them in tent camps in front of the big cities and forbidding them to acquire property, he prevented them from settling in, thus saving them from fragmentation and loss or defacement of their language. The third caliph Uthman (644–656) had the first official version of the Koran drawn up, and the fourth caliph Ali (656–661) ordered the standardization of the language when - in his opinion - it threatened to degenerate.

For religious reasons, all four caliphs insisted on teaching the language of divine revelation, spreading it, cultivating it and protecting it from any corrosive external influences, which they obviously succeeded in doing.

Umayyads

The epoch of the Umayyad dynasty (661–750) is characterized by the extensive Arab-Islamic conquests, which led to a change in lifestyle as the Arab conquerors began to mix with the conquered population. Damascus as the seat of the new caliphate seemed to have completely overshadowed the peninsula, the motherland of the Arabic language. But interest in the language continued.

The Umayyads remained true to the language of their ancestors and the Koran. There is plenty of evidence to suggest that some caliphs believed that the best education could only be enjoyed in the desert. For this purpose, for language training and to experience the spirit of life in the desert, members of the ruling family were sent there.

At the Caliph's court, a cultivated language was considered a sign of nobility, correct Arabic and eloquence were prerequisites for higher positions. A thorough knowledge of Arabic and grammar was even one of the prerequisites for succession to the throne.

The Umayyads were above all closely connected with the traditional poetry that the desert produced, with the poet playing a role similar to that in pre- and early Islam. As a mouthpiece for the public, he supported the rulers or was their avowed opponent. In addition to poetry, rhetoric also played an important role. The rhetorician was expected to express his thoughts in eloquent and sonorous language, on which essentially his success was based. So it is not surprising that the two governors Ziyad ibn Abih (d. 676) and al-Haggag (d. 714) gained fame less because of their warfare than because of their eloquence. The sermons of Hasan al-Basri (d. 728) also served as models for contemporary and later speakers. All in all, prose developed into an important form of language, the founder of which was Ibn al-Muqaffa ' (d. 757). His works became exemplary for the subsequent Arabic prose and an important part of beautiful literature ( adab ).

In less than a century, the Umayyads succeeded in spreading the language and making it a means of literary expression. As early as the beginning of the 8th century, the caliph Abdalmalik ibn Marwan (685–705) took a series of measures to secure the primacy of the Arabic language in the vast Islamic empire. As a state-political act, Arabization began with far-reaching consequences for the spread of the language. Official registers and important files, particularly those of the tax authorities, have been translated into Arabic. From now on it was imperative to use Arabic in all administrative procedures. In the state economic monopolies, for example in the Egyptian factories for the production of papyrus and other luxury materials, Arabization began seriously. New gold coins with Arabic inscriptions took the place of the Byzantine and Persian ones.

The Caliph Abdalmalik implemented a number of reforms to make the language more concrete. Among other things, they consisted in the setting of diacritical points to differentiate between identical letters and in the use of vowel symbols to make it easier to learn the language and to ensure correct reading. As a result, many non-Arabic speakers learned the language of the conquerors and were given the opportunity to hold public offices.

Arabization now stood on a firmer footing and contributed significantly to the spread of Arabic over a wide area. As the official and cultural language, it replaced Greek and Aramaic in Syria and Palestine, Coptic in Egypt, Latin and Berber dialects in North Africa and Spain, and Persian and other languages in the eastern provinces. The Arabic language had acquired an adequate vocabulary in jurisprudence, rhetoric, grammar, administration, theology, and other disciplines, but lagged somewhat behind in philosophy, medicine, and science.

The great achievement that the Umayyads left as a legacy laid the foundation for the later development of the Arabic language under the Abbasids.

Abbasids

With the Abbasid Caliphate (750–1258) of Baghdad, a new era in the history of the Arabic language began. The spiritual center of culture shifted to the cities of Iraq. The Bedouin world of thought, which was so familiar to the formerly ruling Umayyads, could of course not have the same status with the Abbasids who came to power with the help of the Persians, as this inner relationship with Arabism was alien to them.

Characteristic of the early Abbasid period was the constant cultural competition between Arabs and Persians, who accepted Islam and mastered Arabic in spoken and written, but who proudly perceived their new position both at the court of the caliphs and in cultural life. Not infrequently they exhibited their social rise from the status of so-called clients ( mawali ) to the ruling class. The Arabs found the invaders a challenge and began to emphasize the values rooted in the ancient Arab tradition. The Arabic language benefited greatly from this rivalry and had reached its peak in the 10th century.

Urban poetry particularly flourished in the royal seat of Baghdad, founded in 762 . The strict forms of the old odes have been relaxed and expanded to include a new subject area. One of the first to turn away from conventional poetry was the poet Abu Nuwas (d. 810), who was highly favored by the caliph Hārūn ar-Raschīd (786–809).

An abundance of translations, mainly from Middle Persian, not only encouraged the flow of new ideas and content into Arabic, but also created a new style. The Persian Ibn al-Muqaffa ' (d. 757), known for his translation of the animal fables collection Kalīla wa Dimna , used elegant and clear language. He renounced the richness of the old Bedouin vocabulary, which was customary up to that point, as well as the conventional syntax and thus played a decisive role in shaping the modern prose style that was characteristic and trend-setting for the early Abbasid period.

With the increased penetration of the non-Arabs into the literary domain, the gradual transition from Bedouin to urban culture took place.

When paper production began to full extent around 800, translations and imitations of Persian novels, which for several decades had the first place in the cultural landscape, increased everywhere. Under the heading of "correct behavior" (adab), a new category of literature of simple style and entertaining character found widespread use and enjoyed general popularity in urban society. In the form of anecdotes and novels, the adab literature aimed primarily at teaching court officials, secretaries and administrators to convey social manners and correct behavior. One of the real creators and brilliant representatives of modern Arabic prose was the versatile writer al-Gahiz (d. 868), who barely left out a subject in his extensive work. His polished style found imitation and profoundly influenced the Arabic language and literature. The increasing number of foreign-language peoples converted to Islam made it necessary, especially in the mixed culture of the cities of Iraq , to facilitate learning of Arabic and to clear up or avoid misunderstandings of religious texts.

In Kufa and Basra one devoted oneself to the study of grammar as a necessary auxiliary science for the areas of literature and theology. Both grammar schools, which often went their separate ways in explaining linguistic phenomena and later lost their importance as spiritual centers in favor of Baghdad, enjoyed high esteem in the Islamic empire and experienced their heyday until the end of the 12th century. The Muslim grammarians were eager to identify language errors and deviations from the classical language, to determine the correct forms, to collect the pure and extensive vocabulary, proverbs and poems of the peninsula in order to counteract the threatening degeneration process of standard Arabic.

Through the translation institute »House of Wisdom«, founded on the initiative of the Caliph al-Ma'mun (813–833), in which numerous writings by Greek authors were translated into Arabic, and through the new methods and Islamic views adopted from foreign peoples Forms of thought, a complex wealth of creative works of a high scientific level crystallized. In addition to the so-called Arab sciences, the disciplines of philosophy, astronomy, medicine, mathematics and natural sciences flourished, which later found their way to the West mainly from Spain in the Latin version. Classical Arabic was no longer just the language of poetry, but also that of science, which was able to express the most complex facts appropriately.

Sparing neither expense nor effort and anxious to give their name prestige and validity by generously promoting scientific endeavors, the caliphs and greats of the empire drew a selection of Arab and Persian scholars, Muslims, Christians and Jews into their circle.

Decline

It is extremely difficult, if not impossible, to pinpoint a point in time or factor that sparked the decline of the Arabic language and culture. The roots may go back to the 10th century when the Islamic empire was hopelessly divided. Despite the intellectual heyday of this period, the split in the 11th century had serious consequences.

The rapid rise of Arabic from the language of poetry and the Koran to the language of science arose, among other things, from the need of the Arabs for linguistic unity on the basis of Islam. However, this need was already dwindling in the 11th century. Due to excessive dogmatism, literary work gradually lost momentum and slowly but surely headed towards decline. Never before had the Arabic language reached a higher level of development than at the moment when all creative activity began to decline in value. While the Arabic language continued to serve Muslim scholars as a means of teaching and science, the number of those who used it as a literary language declined and was reserved exclusively for those whose minds moved in narrow paths and who were often devoted only to religious questions. Rhyming prose, emphasizing form at the expense of content, was widespread and used without hesitation. A major factor contributing to the decline or intellectual stagnation of Arab culture may also be the fact that East Asians repeatedly invaded Muslim areas. The Seljuks , a Turkic people, accepted Islam, but promoted Persian as the state and literary language in some eastern provinces. During the 13th century, the Mongol hordes brought devastation and devastation to the Asian part of the Islamic world. Baghdad, the center of spiritual life in Islam, was completely destroyed in 1258. Libraries and educational institutions were completely destroyed. Although this cultural center temporarily relocated to Egypt, North Africa and Andalusia, clear signs of decay were visible even where the Islamic tradition was still flourishing.

The attitude of Muslims to secular sciences began to change noticeably, and a return to traditional sciences took place. Ibn Chaldūn (1332-1406), one of the outstanding historians and social scientists of his time, strictly distanced himself from philosophy and placed it on a par with alchemy and astrology , firmly convinced that all three disciplines were detrimental to religion.

This intellectual attitude is an unmistakable indication of how much Arabic had developed from the Koran language to the language of science and illustrates the spirit of piety and religiosity that prevailed at the time, which can be interpreted as an escape from the recurring unrest and uncertainty of this epoch . There was a lack of stability and calm, the prerequisites for intellectual activity and creative work.

As early as the 14th century, the famous lexicographer Ibn Manzur (1233-1311), who wrote the extensive reference work Lisan al-Arab , complained about the decadent state of the Arabic language and the tendency of the people to prefer a foreign language .

After several setbacks and a systematic loss of Arab identity, the decline could no longer be stopped until the Islamic world finally came under the rule of the Ottomans in the 16th century , who administered most of the areas of the Islamic empire until the end of the First World War and during the course of it in the 19th century had to cede part to the European powers. During this long period the study and cultivation of the Arabic language, which was ideally suited for intellectual creation, was pushed into the background. Although Arabic retained its importance in religious life, it gradually made room for Turkish in the administration, a circumstance that contributed to the fact that Arabic was less and less suitable as a means of expressing new scientific and abstract ideas. The alert and searching spirit had given way to superstition, which from now on was the link within Islamic society. The apparent unity of Islam was sustained less by the power of the spirit than that of the sword.

The Ottomans themselves fell victim to an ultra-conservatism expressed in excessive religiosity. Any innovation, no matter how useful, met with bitter resistance. Whether it was the introduction of printing technology in Turkey in 1716 or the expansion of a street in Cairo in the era of the powerful ruler Muhammad Ali Pasha (around 1770–1849), the clergy always resolutely opposed it. For such and similar undertakings, a legal opinion ( fatwa ) had to be obtained from the Mufti . Permission to include secular subjects in the curriculum of Azhar University in Cairo was not granted until 1883.

Language and literature suffered considerable damage. Arabic lost flexibility and accuracy. After nearly four centuries of Ottoman rule, writing in Arabic was a rarity. The style, sober and sparse, lacked the vitality and expressiveness that characterized the language for centuries. Instead, administrative correspondence was only handled in Turkish and classical Arabic was replaced by a multitude of dialects, which was spoken not only by the general public but also by intellectuals.

The Arab people were less and less aware of the fact that their language in the Middle Ages was one of the most important in the world and an almost inexhaustible source of literary wealth. Until the second half of the 19th century, the time of renewal, poetry and prose, unless they were colloquial, were essentially nothing more than a copy of archaic forms without content.

In poetry there was an even stronger tendency to imitate the ancient Arabic poets. This state of affairs lasted until the beginning of the 20th century, when some Arab authors attempted to free the Arabic literary language from its rigidity and to loosen up or replace the traditional styles with contemporary ones, which gave the Arabic language a new impetus, which it incorporated into the Able to assert itself as the language of education, culture and science. However, it would be absurd to assume that the Arabic language and culture reached a complete standstill during the period of decadence. It was precisely in this epoch that priceless works were created, without which our knowledge of Arabic ideas would be extremely limited.

Renaissance

The disintegration of the Islamic empire into small states did not only result in the immediate decline of Arab culture. Despite the geographical distance, the cultural exchange never completely ceased thanks to the common language. This deep connection of the Arabs with their language and culture did not even stop at the borders and should therefore be duly taken into account in every intellectual movement in the Arab world, since without it the Renaissance would have been inconceivable.

However, the impulses emanating from the western world should not be underestimated. One thinks of the relationship that Lebanon had with Europe as early as the 17th century, but particularly of Napoleon's expedition to Egypt in 1798, the effects of which were enormous on various levels despite its purely military character. Undoubtedly the most drastic and in its effect on the Arab world the most momentous event was the introduction and use of printing in the 19th century. Its importance for the development, expansion and standardization of the written language can best be assessed if one realizes that even today Arabic is far less based on oral communication than on printed literature, and that even today it is basically only printed Arabic can be considered a single language.

For the first time, printing made it possible to no longer reserve the written word for a selected target group, but to make it accessible to a wider readership. Compared to other Arab countries, where publications were subject to massive restrictions, Egypt found itself in a particularly fortunate and enviable position. Newspapers and magazines kept the public informed by disseminating the latest events, current, historical and social issues, which gave rise to lively discussions in intellectual circles. Many Syrians and Lebanese were drawn to Egypt in search of freedom of speech, where they saw their freedom of development secured. They founded newspapers and publishers there. On the book market there appeared a relatively rich offer from the most diverse areas. In various parts of the Arab world, the influence of the Western world was clearly evident. Numerous political, social and scientific institutions were brought into being, and private and state schools were founded. The public libraries made a valuable contribution to the dissemination of knowledge.

The Western model seemed omnipresent and even left its mark on parliaments and constitutions. The urge to Europe and above all to America emerged unmistakably from the steadily increasing number of Arab emigrants in the course of the 19th century and deserves special attention as the Arabs living in emigration brought Western ways of thinking, customs and traditions into their homeland.

The constant confrontation with Western culture and its studies found expression in a number of Arabic publications and had a direct impact on the Arabic language by creating modern stylistic and phraseological variants. On the other hand, there was the growing interest of Western scholars in Arabic studies and the Arabic language, which gave new impetus to the apparently buried cultural awareness of the Arabs. Lively discussions about the old and the new, the purity of the language and outside influences were an integral part of intellectual encounters for decades before a general tiredness of discussion crept in.

From the initially stark contrasts between language critics and modernists and from the constant conflict between clinging to the traditional in the awareness of one's own glorious past on the one hand and imitating the admired western world on the other hand, compromise solutions emerged that are clearly reflected in the works of some writers and translators. Although they made use of the classic literary language, they adapted it to the needs of modern life using loan translations, foreign words and neologisms.

Arabic literature began to awaken from its torpor. Prose and poetry shed the fetters of old forms and styles. The authors again placed more emphasis on the content than on the form. On the breeding ground of self-criticism, accompanied by a feeling of need to catch up, a time of productivity and creativity began.

In the course of the establishment of universities, institutes and technical schools, the improved infrastructure and, above all, the dissemination of press products, radio, film and television, the Arabic language entered a phase of rejuvenation. A kind of New Standard Arabic developed, which moves between high and colloquial language. This tendency is most strikingly evident in today's business and newspaper language, in which the influences of English and French are unmistakable. However, a language crisis that some Arabic and European linguists so often claim does not exist. The crisis, if any, lies in the current way of viewing and describing the Arabic language.

Language renewal

- “An overview of the history of foreign influences in Arabic teaches that there was never a time that was so capable of putting the character and character of the language into a state of crisis as the present.” ( H. Wehr : The special features of today's Standard Arabic. 1934)

Since the beginning of the 20th century the Arab world has been drawn into the pull of tremendous upheavals. The orientation towards the West went hand in hand with the confrontation with Western cultures and ideas and the questioning of one's own living conditions. New discoveries and developments in almost all areas heralded an age of general upheaval. With the abundance and diversity of achievements, foreign terms increasingly penetrated the language.

In the shadow of decades of academic and elitist discussions, the Arabic language was so sustainably enriched through translations, and above all through the press, that the creation of new terminology came to the fore as the most urgent task. However, as much as one was generally aware of this necessity, there was disagreement in the choice of method. The purists strictly oppose the inclusion of foreign words on the grounds that it would lead to a long-term alienation of the language. They see the only sure way to preserve the purity and integrity of the language in the creation of new terms by deriving them from Arabic roots.

This view is opposed to the reservations of a second group, who advocate the use of foreign words in their unchanged form, since in their opinion the original meaning is preserved in this way.

Finally, a third group tries to find a way between these two extremes. She takes a moderate position by advocating that the adoption of foreign words should only be the last resort if the attempt to find Arabic equivalents or to integrate them has failed. This attitude was made a principle by the academies of Damascus, Cairo, and Baghdad.

The efforts, which were not limited to the academies but also originated from individuals, deserve attention insofar as the vocabulary has been replenished for almost every area, although it has not been possible to achieve uniformity in the use of the newly formed words. For example, an Arabicized form is used for the word physics in Syria and Iraq, whereas an Arabic equivalent is used in Egypt.

In the future, too, such differences cannot be avoided in view of the extensive Arabic-speaking area, quite apart from the fact that a language renewal, which is naturally constantly in flux, is unthinkable without contradictions.

Language academies

- “That there is a linguistic conscience again today in this time of crisis and despite this crisis and that a limited part of literature follows the paths of the classical language, the advocates of fusha الفصحى can see a gratifying feature of this time.” ( H. Wehr : The peculiarities of today's standard Arabic. 1934)

The " Academy for the Arabic Language in Damascus مجمع اللغة العربية بدمشق" founded in 1918 is the oldest language academy in the Arab world. Since 1920 she has published a magazine on a regular basis. Other important academies are that of Cairo , founded in 1932 and the " Iraqi Scientific Academy ", founded in 1947. Since 1976 there has also been a " Jordanian Academy for the Arabic Language in Amman".

The "Permanent Office for the Coordination of Arabization in the Arab Fatherland in Rabat", established by the Arab League in 1961, is currently one of the most important institutions for maintaining the Arabic language in the Arabic-speaking area. As a national academy ob, it is his task to create binding terms for the modern vocabulary in science and technology for the entire Arab world. His research reports appear regularly in the journal »Die Arabische Sprache«, which he publishes and which is distributed free of charge in large numbers.

Linguistics

- "Honor to which honor is due - the Arabs have done for their language what no other people on earth can show." ( Max Grünert : The umlaut in Arabic. 1876)

The fact that, on the one hand, the Koran was untranslatable according to Islamic belief and, on the other hand, the number of foreign-language non-Arabs converted to Islam in the course of the extensive conquests increased, may have prompted the Arabs to systematically research their own language. But the existing contrast between the language level of poetry and the Koran on the one hand and that of the dialects on the other probably encouraged reflection on the Arabic language and the development of its grammar.

Based on the reasons mentioned, the establishment of rules was necessary in order to facilitate the learning of Arabic, to guarantee the most uniform possible interpretation of the Koran text and the tradition and, above all, to avoid or prevent misunderstandings. This explains the fact that the first linguistic studies were purely practical and that the Koran readers also dealt with grammar.

Grammar writing

Around the middle of the 8th century, two rival grammar schools sprang up in the Iraqi cities of Basra and Kufa, which later became part of the Baghdad school. But the methodology and way of thinking of the Basra school remained predominant in Baghdad.

The Basrier's method was based on the principle of analogy, according to which the regularity of language is in the foreground. Hence the analogist was inclined to correct everything that he considered to be exceptional in language. According to his understanding, language was essentially systematic and classified in models of rules.

The Kufier as anomalists did not deny that regularities exist in the formation of words, but pointed out the manifold forms for whose formation the principle of analogy offered no explanations. For this reason, the exceptions and special forms were of particular interest to the Kufier. They developed an avid collecting activity, which was particularly beneficial for lexicography.

The processing of the grammar in both schools was based primarily on the Koran, the careful observation of the Bedouin language and the evidence of pre-Islamic poetry collected by grammarians, which up to that time was only transmitted orally and of which parts were written down for the first time.

According to Arabic sources, Abu l-Aswad ad-Du'ali (d. 688) is named as the first grammarian and inventor of the vowel signs for the school of Basra . But the systematic linguistic study of grammar began with al-Khalil ibn Ahmad (d. 787), who wrote the earliest Arabic lexicon. He is also considered the first to classify the Arabic sounds according to their place of articulation and to set up the basic rules of Arabic metrics according to a system. His pupil, the Persian Sibawaih (d. 793), is one of the most famous representatives of the Basrian grammar.

Sibawaih left behind the standard work "Das Buch", which later philologists regarded as incontestable and unsurpassed. His main merit was the systematic explanation of phonetic phenomena, with the influence of his teacher al-Khalil also being unmistakable in this regard. He described the organs of speech and the formation of sounds very precisely, classified the Arabic sounds according to the various points of articulation and types of articulation, and recognized the voicing and voicelessness of consonants. Furthermore, he explained impressive phonetic phenomena such as sound change, sound connection, vowel harmony, assimilation, umlaut - a phenomenon that was only explained in the German language in the last century - and much more that is largely confirmed in modern experimental phonetics. In the royal seat of Baghdad, the so-called mixed school emerged at the end of the 9th century, the task of which was to bring about a synthesis of the two language systems. From this amalgamation, which finally prevailed in the 10th century, the grammatical system of Arabic emerged, which we find in a number of works by later linguists. Apart from a few attempts in recent years to facilitate traditional grammar, it has largely retained its original character to our present day and is still an integral part of the curriculum in schools and universities in all Arab countries.

According to his biographer, Avicenna is said to have studied the grammar of Arabic. The font he designed for this purpose, entitled The Language of the Arabs , remained a draft.

lexicography

- “In all of world literature, only the lexicographical science of the Chinese can compete with the Arabic lexicography. How many sacrifices in life and enjoyment of life, how much tireless collecting work and how many years of patience it took to compile a gigantic work like Lisan al-Arab, we can hardly imagine today. "( Stefan Wild : Das Kitab al-'ain ... 1965)

The lexicography , recording and explanation of the Arabic word good, took an enormously important place as an independent discipline within the Arab Sciences. Like the origins of grammar, Arab historians attribute the emergence and interpretation of lexicography to religious factors, namely the need to preserve the word of God and his Messenger. But the earliest works also have a wealth of linguistic material from pre-Islamic poetry. In the Arabic lexicons, as is generally the case, the alphabetical or semantic arrangement is used. In the latter case, the terms are listed according to how they belong together.

Since in the Arabic language system it is not the word but the root that takes center stage, all derivatives appear under the same. Almost all Arabic lexicons are based on this principle, which naturally includes etymological aspects. It follows that the use of an Arabic reference work requires thorough knowledge of the derivation system of Arabic grammar. To make it easier to look up, some dictionaries have been drawn up based on the European model in recent years.

Language theories

- »Sine linguis orientalibus

- nulla grammatica universalis "

The essence of a systematic science consists in the formation of theories which sometimes appear incomprehensible due to their factual subtlety and are therefore sometimes criticized lightly. This applies to language theories in general and to traditional ones in particular, since the time aspect plays a crucial role here. Consequently, the assessment of these theories should not be viewed in isolation from time, place and other complex factors. What has been said can best be clarified with the help of the occidental discussion about the origin and development of language.

That language is not a work of God and not on a Saturday in 3761 BC. Was put into Adam by God, seems to us today to be taken for granted. But when Herder dared to question the belief in the divine origin of the language in 1772, some thinkers of that time felt so provoked that they tried to put this innovator right with their fiery writings. As far as we know today, Herder's statement is without a doubt worthless, but at the time it was not without effect.

Muslim thinkers, of course, had similar issues for centuries. A wide range of basic questions of language have been discussed in countless Arabic works, of which only a few can understandably be touched upon in an introduction. Since it does not seem expedient to theorize about language theories at this point, a selection of ideas from oriental and well-known occidental linguists is offered below as a suggestion. The comparison of both ways of thinking should show the reader important analogies or differences in a clear way.

Definition of language

- "Language is a repository of sensually perceptible signs which, alone or connected to one another, serve to facilitate understanding." ( Brockhaus : Enzyklopädie, 1972.)

- "It consists of sounds through which every people expresses its intentions." ( Ibn Djinni (934-1002). )

Origin of language

- “The divine origin of language explains nothing and cannot be explained by itself. The higher origin is, as pious as it seems, absolutely ungodly. "( Herder : 1772.)

- "But most thinkers are of the opinion that the origin of language is based on agreement and convention and not on revelation and divine instruction." ( Ibn Djinni (934-1002) )

Origin of language

- “Man invented language for himself from sounds of living nature. The tree will be called the Rauscher, the West Säusler, the source Riesler. "( Herder : 1772)

- "Some are of the opinion that the origin of all languages is based on the imitation of audible sounds such as the echo of the wind, the crack of thunder and the rush of water." ( Ibn Djinni (934-1002) )

- "There will never be any final certainty with regard to the origin of human language." ( D. Jonas, 1979 : The First Word)

- "In my opinion, the discussion of this question is unproductive." ( As-Subki (1327-1370) )

Language acquisition

- “By language acquisition we mean that process, which extends over several years, through which children from the initial stage of repeating the ability to speak through a number of different intermediate stages ultimately achieve a fluent command of their mother tongue.” ( W. Welte, 1974 : Moderne Linguistik)

- "Language is acquired habitually, just as the Arab child hears his parents and others and in the course of time acquires the language from them." ( Ibn Faris (919-1005) )

analogy

- "One can take it as a fixed principle that everything in a language is based on analogy, and that its structure, down to its finest parts, is an organic structure." ( V. Humboldt : 1812.)

- "Know that the rejection of analogy in grammar turns out to be incorrect because the whole grammar consists of analogies." ( Ibn al-Anbari (1119–1181) )

Sign concept

- "The linguistic sign is therefore something actually present in the mind that has two sides ..." "( F. de Saussure : 1931.)

- "The linguistic sign changes according to the imagination in the mind." ( Ar-Razi (1149–1209) )

Arbitrariness of the linguistic sign

- “The tie that connects the signified with the designation is arbitrary ... Thus the idea of" sister "is in no way connected with the sound sequence sister, which serves as a designation; it could just as well be represented by any other sound sequence. "( F. de Saussure : 1931)

- “When we see a figure from a distance and mistake it for a stone, we call it that. When we approach the figure and mistake it for a tree, we give it that name. If we have made sure that it is a man, she is given this designation. This shows that the designation takes place in the spirit, so the designation changes according to the idea. "( Yahya ibn Hamza (1270-1344) )

literature

- “The most striking trait of Arabic literature is an element of the unexpected. Without even a hint of what follows, a new, fully developed literary art breaks out again and again, often with a perfection never achieved by the later representatives of the same art genre. ”( H. Gibb / J. Landau : Arab literary history, 1968)

- "Arabic literature is defined as the sum of the writings written by Arabs and non-Arabs in the Arabic language" ( source? )

poetry

The earliest monument in Arabic literature is pre-Islamic poetry, which already had a fully developed system of meter and rhyme at the beginning of the 6th century. These poems, which were only partially recorded in anthologies in the 8th century, provide impressive evidence of nomadic life in the desert, which educates its inhabitants to observe closely and carefully.

The poet "knowing" not only enjoyed the highest recognition among his tribe as an artist, but was also honored as feared as a seer with magical powers and supernatural knowledge. By believing in his alliance with the demonic, from which he supposedly got his inspiration, he got a special position.

Until the emergence of Islam, it seemed as if the Arabs of the desert were only offered poetry, with its precise metrics and the end rhyme, as a suitable means of expressing his creative statements, something his language practically challenged him to do.

The oldest surviving collection of poems ( Dīwān ) includes seven master odes, the so-called “appended ones”, who, according to legend, were awarded a prize at the annual fair of “Ukaz” near Mecca after a competition and hung in gold letters on the walls of the Kaaba should be.

Diversity, precision and brilliant technology, paired with an almost inexhaustible wealth of differentiated vocabulary and lush imagery, are essential features of the ancient Arabic ode, the individual phases of which are still unclear.

As a rule, the ode consists of three parts, with each verse generally containing an independent statement. The poet began with a foreplay, the lamentation at the orphaned home of his beloved and the fateful separation from her, then went on to describe his perilous desert ride to her, described his exhaustion from the scorching heat, lamented his flagged mount and finally came to Main part, the praise of the generosity of his host and patron or to the abuse of his opponents or the tribal leaders, who showed him a lack of hospitality. Of course, Bedouin virtues such as bravery, nobility, boldness and pride were emphasized.

With the advent of Islam, ancient Arabic poetry took a back seat and only experienced a new boom at the end of the 7th century. At that time the love poetry was written in Mecca and Medina, which had a lasting influence on the later poets under the Umayyads (661–750).

Under the Abbasids (750–1258) the new capital, Baghdad, became the center of literature and the arts. The change in social life gave rise to new trends and alien elements, which were also noticeably reflected thematically in poetry. Unusual pictorial expressions and a smooth language characterize a new style, which the philologists at the time disparagingly called the "new and strange".

Prose, which was completed at the beginning of the 9th century, supplanted poetry, which until then had remained trapped in its own conventions. The Syrian poet Abu Tammam (d. 846) made a first attempt to get rid of these conventions by combining the archaic Bedouin poetry with the decorative elements of the "new and strange" style. The collapse of the central power of Baghdad resulted in a shift of literary creativity to the courts of influential princes. This was the case, for example, in Aleppo , the capital of the Hamdanids , in which outstanding poets and writers gathered around the generous, art-loving prince.

In the 11th century, the diversity and originality of poetry gradually began to solidify. The external form was maintained and emphasized with all linguistic means at the expense of the internal design. Traditional motifs were treated superficially, topics and content were watered down through repetitions.

In Andalusia at the beginning of the 13th century a new form of dialect love songs in rhyming stanzas emerged, which from there reached the Arab East via North Africa. Even Sicily , which was 965 to 1085 under Muslim rule, produced a number of poets.

At least since the conquest of Egypt and the holy places of Mecca and Medina by the Ottomans in 1517, the Arab countries fell into a deep literary passivity that lasted into the 19th century. During this time poetry came to a standstill, with the exception of a few poems written in the regional dialects. However, this should by no means mean that the cultural lethargy that occurs can only be blamed on foreign rule.

In the course of the reorientation of some Arab intellectuals in the second half of the 19th century, Arab literature awoke from its paralysis. Translations of European works into Arabic had a positive effect on this new development and set in motion a process of rethinking, the traces of which in Arabic literature became increasingly clear in the course of the following decades. Poetry, however, was to a lesser extent and later than prose subject to the influence of Western ideas. The earliest poets of this time drew primarily from classical poetry. Themes, motifs, rhyme and meter were more or less based on traditional poetry. The poets regarded the sophisticated style of classical Arabic, which appeared as sophisticated as it was artificial, as a model. But gradually historical, social, religious, political and economic issues also took hold.

One of the first modernists and romantics was the Lebanese Khalil Mutran (1871–1949), who came to Paris as a young man and spent most of his life in Egypt. The extremely productive Mutran, who barely left out a topic at the time, succeeded in breaking away from the rhyme technique and metrics as they were familiar to traditional poetry. This laid the foundation for the renewal of poetry, which helped other poets to a new high point.

In this context, the poets of the emigration should not be left unmentioned, who made a valuable contribution to the renewal through their expressive poetry permeated with idealism. It was Christian Lebanese and Syrians who saw their task in the role of mediator between oriental and western cultures. Their bilingualism gave rise to new ideas and motifs that enriched the Arabic language in the long term.

The actual discussion about the renewal of Arabic poetry sparked the critical literary theoretical work of the Egyptian blind scholar Tāhā Husain (1889–1973) on pre-Islamic poetry in the 1930s . Younger poets finally broke with the old tradition and freed themselves from the rigid laws of classical metrics in their poems.

The defeat of the Arabs in the Six Day War in 1967 inspired many poets to write lamentations in which disappointment, despair, sadness and pessimism are openly revealed.

prose

- "It is relatively little known that apart from the Koran and the stories from the Arabian Nights there is an unusually diverse range of Arabic literature that has survived." ( H. Gibb / J. Landau : Arabische Literaturgeschichte. 1968)

Apart from the Koran as the first unique literary creation, prose as a literary medium was limited to office documents and instructions until the middle of the 8th century. The earliest prose writings known to us are three letters from a court secretary of the last Umayyad caliph Marwan II (745–750).

When the interest in the Arab past grew at the court of the Caliph of Baghdad, the old Arabic narrative material, which consisted of Bedouin feuds, proverbs or fables and, in Islamic times, legends about the life and victories of the Prophet and his companions, began to grow. The term »fine education« ( adab ) gave rise to a separate genre of literature that dealt with different topics.

Ibn al-Muqaffa ' (d. 757), who came from Persia and was a pioneering Adab writer, achieved recognition and fame through translations of works from Middle Persian. He left behind a collection of animal fables, writings on morals and ethics, short stories and proverbs.

The Adab works by the Basra-born writer al-Djahiz (777–868), who played a leading role in the intellectual circles of Baghdad, Basra and Damascus, are well known. In his work, which comprises more than 150 writings, he dealt with historical, political and theological questions, as well as topics from the fields of botany, zoology, sociology and ethnic psychology. His best-known books include the "Buch der Ellesamkeit und Darstellung", a treatise on rhetoric, the "Book of Misers" and the "Animal Book", in which the author, who is extremely critical of observation, suggests the theory of evolution and the connection between climate and psyche sets out. In numerous epistles he described typical professions, ways of life and customs of certain population groups in a style that was as perfect as it was witty.

One of the most important writers is al-Isfahani (897–967), who left behind the twenty-volume encyclopedic collection "Book of Songs". This work conveys insightful knowledge about the social life of that time. With the countless anecdotes about singers, composers and poets as well as the lively and vivid descriptions of various historical and social events, this encyclopedia remains without a doubt unsurpassed to the present day.

The Arabic rhyming prose, which was preferred in epistles and sermons and has been very popular since the 10th century, gave birth to the new literary genre " maqama " (lecture), the form of which is partly the drama partly the novella and is similar in concept to the picaresque novel. But it wasn't until a century later that this elaborate rhyming prose came to full fruition. The Basra-born al-Hariri (1054–1122) introduced them to intellectual circles and made them popular. With his collection of 50 maqamem full of wit and originality, he secured a permanent place in the series of masterpieces of entertaining Arabic literature.

The phenomena of decline that took place within classical literature favored the emergence of a folk literature that was gradually able to assert itself. A collection of oriental fairy tales and anecdotes, which later became part of world literature, was published in the 12th century in Egypt under the title Thousand and One Nights . They probably go back to a 10th century anthology of a thousand stories of various origins that contained Iranian and Indian elements.

In the 14th century Islamized areas of Eastern Europe, Russia, China, India, Malaysia and Central Africa, literature was limited to historical and theological topics.

In China, Muslim authors wrote their works exclusively in Chinese, although they devoted themselves to studying Arabic scripts. In contrast, Turkish authors made use of Arabic and left behind a considerable number of works.

In the period that followed, up to the 19th century, a certain flattening became apparent in beautiful literature. With a few notable exceptions, the writers and their works slipped into mediocrity.

The prerequisites for the emergence of modern prose and the free development of the writer in the Arab countries were extremely unfavorable at the beginning of the 19th century. Centuries of foreign rule and intellectual lethargy meant that the use of standard Arabic as the only medium of literature was largely reserved for an elite.

The local dialects prevailed, and that class that had to support the intellectual life in a society was still too small. Above all, however, there was still largely a lack of readers who could not be addressed due to the widespread illiteracy.

But all these obstacles seem to have had a positive effect on strengthening national consciousness, an awareness that naturally called for state independence and independence. In the second half of the last century there was an awakening in the cultural field. There was catching up and catching up with world literature at the beginning of our century.

Four Egyptian intellectuals who paved the way for modernism and whose impact and influence extended far beyond literary work deserve special attention at this point. All four were shaped by realism in its various forms, a realism that had incorporated numerous elements of the reformist spirit of modernity.

Tahtawi (1801–1873) was one of the first Arab modernists. In 1826 the first Egyptian study mission took him to France. After his return in 1831 he was in charge of the state translation agency and the language school, as well as organizing the general school system. He called for schooling to be extended to all strata of the population. With translated works and his own writings, he paved the way for European ideas of culture and society to enter the Arab world and thus laid the foundation for the reform movements that followed.

Afghani (1839–1879), founder of Islamic modernism , lived in Cairo, from where he was expelled in 1879 for political activities. His wandering life took him to his home country Afghanistan, Turkey, India, Persia and Europe. In his writings and agitations he advocated the liberation of the Islamic states from European domination, called for the introduction of free institutions and propagated the unity of all Islamic states.

His student Abduh (1849–1905) was also banished after a brief teaching post in Cairo. After six years of exile, he began reforming Azhar University in 1889 and was appointed Chief Mufti of Egypt in 1899. The core of his teaching consisted in bringing Islam into harmony with the innovations of the West. A writer and thinker cut from a different cloth was the Copt Salama Musa (1887–1958), who in 1913 after his stay in London and Paris became the first Arab to publish a treatise on socialism. It was also he who founded the first socialist party in Egypt in 1920. In forty-five works, Musa discussed political, economic, social and cultural issues. He strictly rejected the return to the cultural heritage of the ancestors and advocated the modernization of the Arabic language. His combative spirit manifests itself very clearly in his autobiography, published in 1947: »I fight against this rotten Orient, in which the worms of tradition root ... I am an enemy of those reactionaries who oppose science, modern civilization, who Are the emancipation of women and get entangled in mystifications ”. Twenty years earlier he was calling for the Orient to be oriented towards Europe, declaring in the foreword of his book “Today and Tomorrow” with an extremely provocative naivete: “We have to leave Asia and turn to Europe. I don't believe in the Orient, I believe in the West «.

Based on this basic attitude, which other thinkers and writers of the 19th and 20th centuries also took - albeit in a moderate form - it is only plausible that the narrative prose was inspired by English, French and even Russian models. Thanks to the introduction of printing technology and the newspapers and magazines founded by some Syrian and Lebanese emigrants in Egypt, the new ideas of Western writers such as Rousseau, Maupassant, Hugo, Dickens, Scott, Gorky, Tolstoy and others found their way to the relatively small readership. In summary, it can be said of modern prose that the political upheavals and social conflicts of the 20th century, as well as the clashes with Western culture and the serious pursuit of cultural renewal, profoundly influence Arabic prose literature and continue to fertilize it. Realism, attentive observation and sober analyzes of the realities of the modern age are in the foreground, knights and heroes according to traditional ideas are no longer in demand, even taboo, and above all the literary mystification and glorification of the glorious past have completely disappeared. The subjects dealt with are therefore varied; they clearly reflect the recent past and present.

In contemporary prose, which unfolds in different directions, but has surprisingly uniform features throughout the Arabic-speaking world, all conceivable contents and shades of modern world literature appear in a colorful oriental garb. But there are also borrowings from Western literature.

Dialects

When speaking of “Arabic”, one must necessarily start from the following fact: In addition to the standardized written language, there are numerous regional dialects in the Arabic-speaking area that function as colloquial languages and are used equally by the educated and uneducated in everyday life. These dialects are not written and are more or less different from one another.

The written language or the modern standard Arabic language is based on classical Arabic and is very different from the spoken variants of Arabic. In a nutshell, this linguistic situation can be described as follows: While the standard language is written but not spoken, dialects are spoken but usually and officially not written. The situation is therefore comparable to that in German-speaking Switzerland.

- "The undisputed multitude and diversity of today's Arabic dialects, however, all too easily obscures one aspect under which they can also be seen: namely an astonishing typological uniformity." ( Werner Diem : Divergence und Konvergenz im Arabischen. 1978)

Dialects have been attested since the 9th century and have preserved much of what has standardized the written language with its normative character up to the present day. Therefore, knowing the Arabic dialects - apart from their practical value - is of utmost importance for understanding and researching the historical processes of the written language.

There is no reliable evidence of the origin and development of the Arabic dialects. On the basis of more or less useful clues, two views emerged:

- The dialects only emerged after the spread of Islam outside the Arabian Peninsula and through contact between the Arabs and other peoples. The language form of the pre-Islamic poets as well as that of the Koran was identical to the colloquial language of that time.

- Already in pre-Islam there were two different forms of language: the language of poetry - high language - and the colloquial language - dialects - in which the final short vowels were not spoken.

Be that as it may, the close contact between the Arabs and the inhabitants of the territories they conquered was undoubtedly essential for the development and development of the individual dialects.

The sources for researching the Arabic dialects and their historical development are of course not limited to the dialects currently used, but there is a wealth of material that can be found in the form of isolated remarks in the works of the Arabic grammarians of the 8th and 9th centuries. Century. This contains linguistic deviations and special forms of the various Arab tribes. The information about the pronunciation of the Koran readers at that time also provides information about the phonetic relationships that prevailed at that time.

Furthermore, the writings of the Arabic philologists on "the language errors of the people", written since the 9th century, represent a veritable treasure trove for researching the state of the language at that time. Important sources are also numerous writings that were mainly written by Christian and Jewish authors who had an extremely inadequate knowledge of the classical language and, as a result, their scripts were interspersed with dialectal phenomena. The language form created in this way is referred to as " Middle Arabic ".

Finally, reference is made to the Arabic loan and foreign words in other languages. The Spanish-Arabic language is particularly suitable as a rich source for this, as it provides illuminating insights into vowelism and the pronunciation of some consonants as well as transformations in the theory of forms.

structure

The Arabic dialects can basically be divided into those of the "sedentary" (town and village) and those of the "Bedouins". Both terms are used purely formally and say nothing about the status and way of life of the speakers.

Typologically, they roughly describe two dialect groups with certain characteristics that are most noticeable in the phonetic system. The preservation of the sounds th and ie in the Bedouin dialects stands out from all the characteristics, while in those of the settled dialects they have partly become t and d, partly s and z. Another characteristic of the city dialects is the sound shift of the q to the vocal paragraph, while the pronunciation q or g predominates in the Bedouin dialects. It is also worth mentioning the pronunciation of the dj as g in the dialect of Cairo.

The Arabic dialects are geographically divided into five language areas according to prevailing custom. Viewed individually, they usually form a unit and show a large degree of agreement with one another, so that speakers of different dialects generally do not have any communication difficulties. The five dialect groups are:

1. Peninsula Arabic : The dialect groups known in this language area are:

- a) The North Arabian Bedouin dialects, which break down into the dialects of the Syrian-Iraqi border area. These include the eastern dialects of Kuwait, Bahrain, Qatar and the Gulf States.

- b) Hidjaz dialects (Mecca).

- c) Southwest dialects (Yemen, Aden, Hadramaut, Zufar).

- d) Oman dialects.

2. Mesopotamian Arabic : The language area includes Iraq, south-east Turkey and a small area of north-east Syria. In northern Iraq, Kurdish is spoken in addition to Arabic, and a small minority speaks the New Aramaic dialect of Ashuri. Mesopotamian Arabic can be divided into two dialect groups, which in turn break down into several dialects:

- a) Qeltu dialects : These consist of the Anatolian dialects (Mardin, Diyarbakir, Siirt, Kozluk-Sason), the Tigris and the Euphrates dialects.

- b) Gilit dialects : Of these, only the rural dialect of Kwayrish and the Muslim urban dialect of Baghdad are known.

3. Syriac Arabic : This includes the dialects of the settled people of Syria, Lebanon, Jordan and Palestine. The Bedouin dialects spoken in this area belong to Peninsular Arabic. Syriac Arabic is divided into three dialect groups:

- a) Lebanese-Central Syrian dialects (Damascus).

- b) Northern Syrian dialects (Aleppo).

- c) Palestinian-Jordanian dialects.

4. Egyptian-Arabic : The language area includes the dialects of Egypt and those of Eastern and Central Sudan. This little-explored language area only allows the division into Upper and Lower Egypt. The latter includes the dialect of Cairo. The Bedouin dialects of Egypt have features of Maghribine or Peninsula Arabic.

5. Maghribinian Arabic : These are today's dialects of Tunisia, Morocco, Algeria, Libya, Mauritania and Malta. Historically, this also included the dialects of Andalusia and Sicily. The huge language area is divided into two dialect groups:

- a) Prehilalian dialects (all dialects of the settled people in this area).