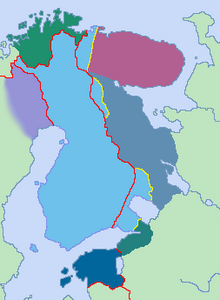

Greater Finland

Light blue: Finland today and territorial losses to the USSR 1940–1944.

Gray Blue: Eastern Karelia

Violet: Kola -Halbinsel

Dark Blue: Estonia

Olive: Ingermanland

Green: The Norwegian province of Finnmark

Purple: The Swedish part of the Torne Valley

The term Greater Finland (Finnish Suur-Suomi ) has been discussed in irredentist - nationalist -minded groups in Finland since the 19th century. He described the idea of an independent Finnish nation-state within its supposedly “natural” borders, which should also include many peoples related to the Finns , in particular the Karelians , Kvenen , Ischoren , Woten and Wepsen .

expansion

The northern sea as the northern border, the White Sea and Lake Onega in the east, and the rivers Swir and Rajajoki , sometimes also the Neva , were often cited as "natural borders" . Therefore, in addition to all of Karelia and the Kola peninsula , the Norwegian Finnmark was also claimed. Even more radical concepts planned the inclusion of Estonia , Ingermanland and Swedish Lapland in order to “liberate” the Estonians and Ingrian Finns, as well as the Sami who are distantly related to the Finns .

The Soviet diplomat Vladimir Petrovich Potjomkin accused the Entente (which had also occupied Arkhangelsk from 1918–1920 ) of being behind the “plans of the Finnish bourgeoisie” to want to form a “Greater Finland”: “... through the rift of Karelia together Petrozavodsk, the Petrograd region including the city of Petrograd [meaning the later Leningrad, today's Petersburg], the Kola peninsula with the ice-free port of Murmansk and the entire north of the Soviet Union to the Urals from the Union of the [Russian] Soviet Republic ” .

East Karelia, the Kola Peninsula and, above all, the northern Russian areas had never belonged to Finland or Sweden at any point in history, or had ever been conquered by Swedes or Finns even briefly, but the Finnish, Ugric and Uralic peoples living there were already in the Middle Ages were subjugated by the then Russian republic of Novgorod .

history

The Greater Finland idea represents a radicalization of the Finnish nationalism that awakened under Russian rule in the 19th century and corresponds to similar ideas in the other forms of European national romanticism , such as the idea of Greater Germany , Italian irredentism or Pan-Slavism . The great Finnish idea shares with them the organicistic idea that a nation has natural borders, the call for the unity of the “ people's body ”, and the endeavor to scientifically substantiate these premises.

In the natural sciences, such a motivated approach can be assumed, for example, from the botanist J. E. A. Wirzen, who, according to geobotanical criteria, located the eastern border of the Finnish natural area on the White Sea. The description of the Fennoscandinavian rock pedestal by the geologist Wilhelm Ramsay was also taken up by nationalist circles in Finland, on the one hand to set themselves apart from Russia, and in turn to expand Finland's natural boundaries. It is no coincidence that Sakari Topelius made these studies the subject of his inaugural lecture at the University of Helsinki in 1854.

Finnish nationalism, however, made particular efforts in linguistics to propagate the biologistic concept of a blood relationship with their speakers through the relationship between the Finno-Ugric languages . The fact that peoples like the Karelians and Kveners were incorporated into the Finnish national body is shown in August Ahlqvist's poem Suomen valta (1860):

|

|

* In a different version than Ruijan suu , ie "at the mouth of Vadsø "

The central symbol of Finnish national romanticism was the Kalevala , a collection of Finnish myths published by Elias Lönnrot in 1835 , which was quickly elevated to the rank of national epic. The fact that Lönnrot collected a large part of the sagas compiled in the Kalevala in Karelia led to the emergence of " Karelianism " (Finnish: Karelianismi ) in the late 19th century , which reached its peak around 1890. Karelianism manifested itself above all in literature and the visual arts and was based on the idea that Karelia was the real fountain of Finnish culture and nation and that Finland was the most original there, i.e. the most “Finnish”. Karelianism contained a lot of political explosives, because a large part of Karelia lay beyond the borders of the Russian Grand Duchy of Finland . As the Finnish independence movement grew stronger, the boundaries of the independent Finnish nation-state to be established were discussed.

See also

Individual evidence

- ↑ Vladimir Petrovich Potjomkin : History of Diplomacy. Third volume, part 1 (Diplomacy in preparation for the Second World War) SWA-Verlag, Berlin 1948, p. 148.