Hansekontor in Bruges

The Hansekontor in Bruges was the most economically significant of the four trading posts of Hanse . The office had a seal with the double-headed imperial eagle , which was given to it by Emperor Friedrich III in 1486 . was awarded and its use can be proven since 1487. The Hansekontor in Bruges was, as one would express it in today's terminology, a representation of the interests of the Hansa recognized under international law and had its own jurisdiction . Merchants from Hanseatic cities working in Bruges were forced members. If one wanted to put this typically medieval institution in terms of its legal character and internal constitution in today's legal categories, one could say: The Hansekontor in Bruges had the position of a cooperative , foreign Chamber of Commerce of the Hanse in Bruges with consular powers. The bearer of any legal sovereignty was not an imaginary legal person, not an institution , but always, from the beginning to the departure of the office, the cooperative of the German merchant in Bruges in Flanders , i.e. a multitude of people, according to medieval thinking. The limits of affiliation were never fixed with absolute certainty, but depended on various, above all political, circumstances. Ultimately, the merchant himself defined who had part in his rights, but not independently of the leading cities.

history

Creation requirements

In terms of trade policy, the Hanseatic League established legally independent offices as a legal entity at some important trading centers abroad, where the trade privileges acquired there and the interests of the Hanseatic merchants working there required special protection. The city of Bruges had become a trade fair center around 1200 and was at the center of Flemish cloth production . Due to a storm surge in 1134, the Zwin in connection with the Reie gave it access to the North Sea, which made it and its outer harbor in the town of Damme, founded in 1180, accessible for the cogs from the North Sea . In 1252 and 1253, Countess Margaret II of Flanders, after negotiations with the Lübeck councilor Hermann Hoyer and the Hamburg council notary Jordan von Boizenburg, privileged the merchants from Lübeck , Hamburg , Aachen , Cologne , Dortmund , Münster and Soest and the other Roman merchants Reiches (several times: et aliis Romani imperii mercatoribus ).

The intersection of international trade and the trade fair in Bruges made the Kontor in Bruges the economically most important of the German merchants. These were called Easterlings here because they all came from cities east of Bruges and Flanders. Bruges offered a seaward connection to London with the Stalhof as a further office, but also trade with the south of France ( Baiensalz , wine ) and the Iberian Peninsula . On the land side, there was a connection to Upper German trade with the cities of southern Germany and northern Italy (tropical fruits as dried fruits, spices). The merchants of the Hanseatic cities of Westphalia and the Rhineland , often closely related to the cities of the Wendish quarter of the Hanseatic League on the southern Baltic Sea coast from the Ostsiedlung , were in the immediate hinterland of this Flemish exhibition center.

The trading lock of 1280

Already in the years 1280 to 1282, in the tense relationship between Count Guido I of Flanders and the city of Bruges, the privileges had to be preserved and, if possible, expanded. The city of Bruges restricted not only German merchants, but also those coming from southern France and Spain, in their room for maneuver through disabilities and harassment, in disregard of their economic importance for the location.

After written reassurance to the cities mainly affected, the City Council of Lübeck decided to act and sent Councilor Johann van Doway to Flanders and Bruges. The city of Bruges and its pile have been boycotted trade . The office relocated from Bruges to Aardenburg in 1280 . The consequences were disastrous for Bruges, and in 1282 the office was finally able to return to Bruges after the old privileges had been confirmed.

Johann van Doway, as one of the early foreign politicians in the Hanseatic cities, successfully implemented the means of Hanseatic trade policy, which had been perfected over the next centuries: first negotiation with top priority and the leverage of boycotts, then economic blockades and finally sea warfare as a pirate war . The means of the Hanseatic trade wars differed significantly from those of the territorial princes, since they were not fought for land gain, but exclusively for monetary privileges and compensation. Foreign territory, on the other hand, was only “ pledged ” to secure compensation that could not be paid immediately.

The importance of the Flanders trade is also underlined by the fact that the Lübeck Council Chancellor Albert von Bardewik laid down the provisions of the Lübeck Maritime Law for the Flemish voyage separately in writing in 1299 .

The second boycott of Flanders

The second boycott of Flanders by the Hanseatic League took place in the years 1358 to 1360 under the direction of the Lübeck councilor Bernhard Oldenborch and led to the same result; the privileges were secured again and the Hanseatic League compensated for the lost profits. Diplomatically, in 1358, the Hanseatic people had Duke Albrecht I of Bavaria, who was also Count of Holland , grant them new privileges for the Dordrecht staging area . That was enough to be able to continue business in Bruges as usual in 1360 after the old privileges there (according to the judgment of the Hansesyndici ) had been legally confirmed by Count Ludwig II of Flanders.

The trade barriers of 1388

A third Boycott of Flanders in the city of Bruges was decided by the Hanseatic Day in 1388 (at the same time as further trade bans against England and Russia) after the local authorities had prevented the office from moving out of the office in 1378, the German merchants were imprisoned and their goods were confiscated. This boycott was not as immediately effective as the previous two. Weavers' revolts had broken out in Flanders , Philipp van Artevelde had taken power in neighboring Ghent and the political situation in the county of Flanders could only be stabilized again in 1382 in the battle of Roosebeke . At the same time, there was no support from the Prussian cities in the Hanseatic camp and the Grand Masters of the Teutonic Order Winrich von Kniprode and Konrad Zöllner von Rotenstein were open to the city of Bruges and Flanders and thus to the so-called Wendish cities around Lübeck (see below), which was internal Finding an opinion and the diplomatic negotiations between Lübeck's mayor Simon Swerting and the Flemish people made it difficult. Negotiations with Philipp the Bold after the boycott began, dragged on for four years until the latter confirmed the privileges again and an agreement on the amount of the severance pay to be paid to the Hanseatic League was reached. With the payment of the first settlement installment, the Kontor returned from Dordrecht to Bruges in 1392 . The diplomacy of the Hanseatic League had triumphed over the Netherlands for the last time.

Bruges decline in the 15th century

After a long period of peace, if not without complaints from the Hanseatic merchants, the situation came to a head again after the Peace of Arras (1435) . As early as 1425, due to the unsuccessful diplomatic mission of Lübeck's mayor Jordan Pleskow, plans to move out of the office were again planned, but because of the conflict with Denmark, this was refrained from. Now the "Hansenmord zu Sluis" led to the immediate relocation of the office to Antwerp , which resulted in a fourth boycott that lasted until 1438. In the port of Sluis am Zwin on June 3, 1436 some Hansen were slain by the local population. On the day mentioned ( Trinity ), some Hansen sat with wine in a tavern in the port city of Sluis, so not in Bruges itself. They were joined by a Flemish, probably not one of the great merchants, but a ship's servant, and teased them. This led to an argument that continued to build up in the streets of Sluis. Finally, a general hunt against all Oosterlings began, in the wake of which between 3 (according to the judgment of the ducal Burgundian court councilor in Brussels of August 15, 1438 under Chancellor Nicolas Rolin ) and over a hundred (according to the largest figures in the Hanseatic and Bruges reports) Hansen, especially boatmen and boatmen, were slain. The deeper cause was an explosive mixture of political and economic tensions: the Duke of Burgundy had changed to the side of the French king in the Peace of Arras and began the siege of the then English Calais with great enthusiasm of the Flemish cities . In contrast, the Hansen were considered friends of England. There was also famine in Flanders and the Hanseatic grain deliveries were pending. Ultimately, there was open hostility between Bruges, which feared for its importance, and the emerging port city of Sluis.

Just two days later, the city of Sluis had three convicted beheaded, which the cities did not accept as atonement. The first boycott measures were only directed against Sluis and avoided Damme and Bruges. In the turmoil of the uprising of the city of Bruges against the duke, the latter finally allowed the office to move to Antwerp. The move out of the office was only interrupted by a payment of damages of 8,000 pounds groschen and on the promise of the Flemish side to track down and judge other culprits.

With the increasing silting up of the Zwin access to the lake in the 15th century, the importance of the city of Bruges as a trading center declined. Now the Hanseatic League decided in 1442 - probably also against the English competition that arose with the people traveling around the Baltic Sea - that only cloth purchased in Bruges could be traded. But as early as 1486 the number of elderly people in the Bruges Kontor was reduced, and in 1520, after appropriate negotiations by the Lübeck Mayor Hermann Meyer , the office was relocated to the sand-free Scheldt in Antwerp, where in the middle of the century under the syndic Heinrich Sudermann by the architect Cornelis Floris II . was built again a large house of Easter charges. However, that did not stop the decline of the office during these troubled times.

Structure, building and staff of the Bruges office

In contrast to the other three Hanseatic offices, the Peterhof in Novgorod , the Tyske Bryggen in Bergen and the Stalhof in London , the Hanseatic merchants in Bruges did not live and work isolated from the local population in Bruges in their own enclosed district, but in social contact with them the citizens of the city. In 1252 the German merchants wanted to build their own enclosed settlement Neudamme not far from Dammes am Zwin, but this extraterritorial solution was rejected by Countess Margarete.

Bruges was also the only office where individual foreign merchants could buy land or rent houses in the city. Therefore, the office in Bruges (unlike the other three) did not initially have its own building. It traditionally used the remter of the city's Carmelite monastery for its meetings . This is also explained by the fact that the large number of German merchants in the city, which at times exceeded 1,000, made accommodation in an enclosed complex simply impossible. However, the foreign merchants from other nations in Bruges, the Lombards, Scots, Genoese and others, were not completely housed in their own buildings. Nevertheless, they all had their own houses to house the Syndici , secretaries, coffers, seals and administrations. The merchants themselves usually lived with Bruges inns. A good hundred of these innkeepers from the late 14th and early 15th centuries have been proven to be hosteliers and business partners of Hanseatic merchants.

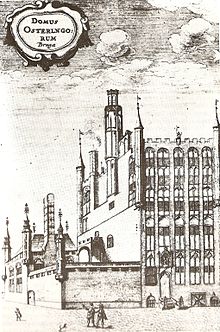

With the Haus der Osterlinge , the Hansekontor only acquired a building in Bruges in 1442, which was replaced in 1478 by a more spacious new building on Osterlingenplein . However, the meetings continued in the Carmelite monastery, whose church was the church of the Hanseatic merchants in Bruges. There, in 1474, the documents of the peace treaty of Utrecht between the Hanseatic League and England were exchanged by the elder Johann Durkop. The Oosterlingenhuis is known to us through several drawings of the lavishly designed facade, which was originally decorated with a striking tower. Only parts of it are preserved today and serve as a commercial building. The current building facade has been changed significantly, but the existing parts are essentially original. During renovation work in 1988 it could be proven that parts of the inner building structure also originate from the time of construction.

The office rules were basically similar to those in all other offices. In Bruges, too, the office was represented by elected elders . But there was no reason for such rigid regulations as those laid down in Novgorod for the Peterhof in the so-called Novgorod Schra . The written version, as far as it has survived, was also made much later.

In view of the importance of Bruges as a trading center for almost all cities of the Hanseatic League, there was a special rivalry between the Hanseatic cities in Bruges for influence on the management of the affairs of the office. This results in the grouping of Hanseatic cities starting from the Bruges office initially in thirds (at the Bruges office since 1347 at the latest, two elderly people for the Wendish-Saxon, the Westphalian-Prussian and the Gotland-Livonian third), later in quarters in which interests are more decisive City groups were "bundled".

However, all the offices had one thing in common, the basic problem of the Hanseatic League's trade based on stipulated privileges: the privileges had to be defended against both local trade and the developing international markets. In this defense of acquired rights, the offices themselves were only the spearhead on site and relied on the support and unity in supporting common interests, according to the traditional view of the Hanseatic cities , which were only loosely united in the Hanseatic League .

Hanseatic merchants in Bruges

The training of a Hanseatic merchant necessitated trips abroad and longer stays abroad in the Hanseatic offices and factories at a young age . The stay of several years in the largest Kontor in Bruges offered career opportunities: those who were elected as the senior man of the Kontor and who proved themselves as such, usually rose to the top as councilor and mayor when they returned to their hometown. The mayor of Lübeck, Hinrich Castorp , is a good example in this context .

The life and economy of the Hanseatic merchants in Bruges becomes clear from the almost complete correspondence of Hildebrand Veckinchusen (1370–1426) in the edition of Wilhelm Stieda , one of the most important sources for assessing and researching the Hanseatic economic history of the late Middle Ages , at the same time a well-documented example of this The rise and fall of a merchant's fate at that time are close together.

See also: List of secretaries at the Hanseatic Office in Bruges

Files and archives of the office

The archives of the Bruges Kontor including the Bruges transcripts of the Hanseatic Trials were moved from Antwerp to Cologne as the closest Hanseatic city in 1594 and are now in the historical archive of the city of Cologne .

literature

- Thorsten Afflerbach: The everyday professional life of a late medieval Hanseatic merchant. Considerations for the processing of commercial transactions. Frankfurt am Main 1993. (Kieler Werkstücke. Series A: Contributions to Schleswig-Holstein and Scandinavian history, edited by Erich Hoffmann, Vol. 7)

- Albert von Bardewik : Specinem juris publici Lubecensis, quo pacta conventa et privilegia, quibus Lubecae per omnem propemodum Europam circa inhumanum jus naufragii ( beach law ) est prospectum, ex authenticis recensuit… qui etiam mantissae loco Jus maritimum Lubecense aiquard de Albertoissard . 1299 compositum ex membranis edidit Jo. Carolus Henricus Dreyer (Ed.), Bützow without giving the year

- Mike Burkhardt: The order of the four Hansekontore Bergen, Bruges, London and Novgorod . In: Antjekathrin Graßmann (Hrsg.): The Hansische Kontor to Bergen and the Lübeck mountain drivers . International Workshop Lübeck 2003 (= publications on the history of the Hanseatic city of Lübeck. Edited by the Archives of the Hanseatic City, Series B, Volume 41), Lübeck 2005, pp. 58–77.

- Joachim Deeters: Hansische Rezesse. A source study based on the tradition in the historical archive of the city of Cologne. In: Hammel-Kiesow (ed.): The memory of the Hanseatic city of Lübeck . Schmidt-Römhild , Lübeck 2005, ISBN 3-7950-5555-5 , pp. 427-446 (429ff.), With inventory signatures in the appendix.

- Luc Devliegher: Het Oosterlingenhuis te Brugge. In: Werner Paravicini (ed.): Hanseatic merchants in Bruges. Part 4: Nils Jörn , Werner Paravicini, Horst Wernicke (eds.): Contributions from the international conference in Bruges, April 1996. Frankfurt a. M. 2000. (Kieler Werkstücke. Series D: Contributions to the European history of the late Middle Ages, Vol. 13.), pp. 13–32.

- Ingo Dierck: The Bruges elderly of the 14th century. Workshop report on a Hanseatic prosopography. In: Hansische Geschichtsblätter 113 (1995), pp. 49-70.

- Ders .: Hanseatic elders and the Bruges leadership. In: Werner Paravicini (ed.): Hanseatic merchants in Bruges. Part 4: Nils Jörn, Werner Paravicini, Horst Wernicke (eds.): Contributions from the international conference in Bruges, April 1996. Frankfurt a. M. 2000. (Kieler Werkstücke. Series D: Contributions to the European history of the late Middle Ages, Vol. 13.), pp. 71–84.

- Philippe Dollinger : The Hanseatic League . 5th, exp. Stuttgart 2012 edition, ISBN 3-520-37105-7 (originally published as La Hanse (XIIe - XVIIe siècles) . Paris 1964.)

- Anke Greve: Bruges hosteliers and Hanseatic merchants: A network of advantageous trade relationships or programmed conflicts of interest? In: Werner Paravicini (ed.): Hanseatic merchants in Bruges. Part 4: Nils Jörn, Werner Paravicini, Horst Wernicke (eds.): Contributions from the international conference in Bruges, April 1996. Frankfurt a. M. 2000. (Kieler Werkstücke. Series D: Contributions to the European history of the late Middle Ages, Vol. 13.), pp. 151–161.

- This: Hanseatic merchants, hosteliers and hostels in Bruges in the 14th and 15th centuries. Frankfurt a. M. 2012. Diss. Gent 1998. (Kieler Werkstücke. Series D: Contributions to the European history of the late Middle Ages Vol. 16. Zugl. Werner Paravicini (Ed.): Hanseatic merchants in Bruges. Part 6.)

- Volker Henn: … dat as up dat reported kunthoer tho Brugger… eyn kleyn upmercken and still lifted… . New research on the history of the Bruges Hansekontor. In: Hansische Geschichtsblätter 132 (2014), pp. 1–45. [Comprehensive bibliography of research on the Bruges office since 1988.]

- Werner Paravicini (ed.): Hanseatic merchants in Bruges. Part 1: The Bruges Tax Lists 1360 - 1390, ed. by Klaus Krüger. Frankfurt a. M. et al. 1992. (Kieler Werkstücke. Series D: Contributions to the European history of the late Middle Ages, Vol. 2.) - Part 2: Georg Asmussen: The Lübeck Flanders drivers in the second half of the 14th century. Frankfurt a. M. et al. 1999. (Kieler Werkstücke. Series D: Contributions to the European history of the late Middle Ages, Vol. 9.) - Part 3: Prosopographical catalog for the Bruges tax lists (1360-1390). Edited by Ingo Dierck, Sonja Dünnebeil and Renée Rößner. Frankfurt a. M. et al. 1999. (Kieler Werkstücke. Series D: Contributions to the European history of the late Middle Ages, Vol. 11.) - Part 4: Nils Jörn, Werner Paravicini, Horst Wernicke (ed.): Contributions from the International Conference in Bruges, April 1996. Frankfurt a. M. 2000. (Kieler Werkstücke. Series D: Contributions to the European history of the late Middle Ages, Vol. 13.)

- Ders .: guilt and atonement. The Hanseatic murder at Sluis in Flanders. In: Hans-Peter Baum, Rainer Leng, Joachim Schneider (eds.): Economy - Society - Mentalities in the Middle Ages. (Festschrift Rolf Sprandel) Stuttgart 2006, pp. 401–451. (Contribution to economic and social affairs, Vol. 107).

- Ernst Schubert: Novgorod, Bruges, Bergen and London: The Hanse offices . In: Concilium medii aevi 5, 2002, pp. 1-50. ( PDF )

- Walther Stein: The cooperative of German merchants in Bruges in Flanders. Berlin 1890.

- A. Vandewalle: Het Archief, het wapen en het zegel van de Duitse Hanse te Brugge. In: Qui Valet Ingenio. Liber Amicorum Johan Decavele. Gent 1996, pp. 453-461.

Web links

(with further links to the Flanders trade)

- Till Cornelius: Hanseatic trade in Bruges

- Oscar Gelderblom: Violence and Growth. The Protection of Long-Distance Trade in the Low Countries, 1250-1650 . (PDF) Utrecht 2005, pp. 1–78 (English)

- Richard Hakluyt : An agreement made betweene King Henrie the fourth and the common societie of the Marchants of the Hans. In: The principal navigations, voyages and discoveries of the English nation etc. (published 1589 and revised 1598–1600).

Individual evidence

- ^ Vandewalle, Archief .

- ↑ The picture of the legal position and constitution of the Hanseatic League, of its personal basis and its constantly changing interests and relationships both internally and externally has been assessed in an extraordinarily diverse manner in research over the past twenty years. The discussion has still not come to an end in all aspects. Comprehensive on this Henn, Forschungsungen, passim, with the further literature.

- ↑ Hansisches Urkundenbuch (HUB) 1, pp. 137ff., No. 121f .; Pp. 140f., No. 428; Pp. 142–158, nos. 431–436 - Mutual favoring of Flemish merchants on the part of the city of Münster, for example HUB 1, p. 167, no. 465.

- ↑ Werner Paravicini, Schuld und Sühne offers a comprehensive and fundamental description of the specific event and at the same time the state of research up to 2006 with new sources.

- ↑ The Carmelite Monastery existed from 1258 until it was completely destroyed by the Calvinists in 1579. There is no engraving with the view of this building. The somewhat confused city map by the painter and sculptor Marcus Gerards the Elder in 1562 alone gives a certain idea of the structure of the building. After John Weale: Quarterly Papers on Architecture , Volume 1, 1844, p. 65 ( digitized version )

- ↑ On the Bruges inns comprehensive: Greve, Kaufmann .

- ^ Schubert: Die Kontore , p. 23.

- ↑ On the history of the building: Luc Devliegher, Oosterlingenhuis .

- ^ Reprint of the revision of the statutes (1374) by Philippe Dollinger : Die Hanse , in the annex to the sources.

- ↑ Stein, Genossenschaft, pp. 25–28.

- ↑ Hildebrand Veckinchusen: Correspondence of a German merchant in the 15th century . Leipzig 1921, full text on Wikisource . The correspondence was put in a wider context in 1993 by Thorsten Afflerbach, Everyday , in a modern perspective with numerous other sources.

- ↑ Deeters, Hansische Rezesse .