Main Customs Office (Munich)

The former main customs office in Munich is a building complex from 1912 at Landsberger Strasse 122–132 in the Schwanthalerhöhe district of Munich . From the opening until 2004, it housed the main customs office in Munich I, and since then it has been used by individual departments of the Federal Customs Administration . The buildings were built in a mixture of late Art Nouveau and reform architecture . They are considered to be an example of the “monumental construction of the Prince Regent's time ” and “represent the size and independence of the Bavarian kingdom”. The massive, 180 m long former warehouse with a glass dome is striking. Its top is 45 m high and looks “like a crystal” growing out of the middle of the building.

Due to its location next to the Donnersbergerbrücke between Landsberger Straße and the railway tracks, the building is very present in the cityscape and can be seen both from the Mittlerer Ring on the Donnersbergerbrücke and from all trains entering or leaving Munich Central Station .

history

Bavaria had already had a modern financial administration with a General Customs and Toll Directorate since 1807 . In 1819, as part of the reorganization of the royal authorities under the constitution of the Kingdom of Bavaria from 1818 under Maximilian von Montgelas, a tripartite structure consisting of the management, main customs offices and subordinate customs offices of the first and second classes was set up. In 1874, the main customs office in Munich was relocated to a building by Friedrich Bürklein on Bayerstraße near Munich Central Station and in 1880 the customs and tolls department was integrated into the new Royal General Directorate for Customs and Indirect Taxes , which meant that tax offices and tax offices were subordinate to the main customs offices. There were two main customs offices in Munich since 1901, when another was opened in Haidhausen at the Munich East train station with responsibilities in the east of Munich up to the then Regional Court of Swabia .

Due to an upswing in long-distance trade and especially a new Customs Act of 1906, the main customs office I was no longer sufficient. Whereas in 1900 24,000 packages of dry goods and 3,560 packages of liquid goods had arrived and cleared, sales rose to 48,000 packages of dry goods and 7,000 packages of liquid goods by 1911. An extension on the property was not possible. Therefore, the government commissioned a new building for the main customs office in Munich I in 1908. For this purpose, the property of the former forstrial timber yard of the royal Bavarian forest administration further west on Landsberger Strasse was selected, which is the extension of Bayerstrasse out of town. To enable access to the property, nine private houses along Landsberger Straße had to be bought and demolished. Because the technical testing and training institute of the customs administration, which had been housed in the old courtyard together with the royal general directorate for customs and indirect taxes, had to move out there, it was to be integrated into the new building. Since the new location was on the outskirts of the city, service apartments were provided.

Design and construction

The building was designed by the royal government and building assessor Hugo Kaiser . Together with three other officials from the building administration, he went on a study trip to modern customs buildings, the Hamburg free port and various industrial buildings that could be used as models. The plans subsequently drawn up provided for a generous draft, the real estimated space requirement was increased by a third as a reserve for the future and was thus included in the requirements for the construction. The design and a model were approved by Prince Regent Luitpold in 1908 . The building complex was built from 1909 to 1912, with Kaiser in charge of construction and the royal ministerial advisor Gustav Freiherr von Schacky auf Königsfeld from the Ministry of Finance in charge of construction. On July 1, 1912, the new main customs office was inaugurated by Prince Ludwig on behalf of his 91-year-old father. The previous location was taken over by the Royal Bavarian State Railways .

The warehouse and administration building were built in reinforced concrete - frame construction and were among the first reinforced concrete structures of this size in Europe. The leading companies of the time from all over southern Germany were commissioned with the construction work. The reinforced concrete structures were carried out by the Munich construction companies Gebr. Rank and Heilmann & Littmann , the wrought iron work came from FF Kustermann . The heating system came from Eisenwerke Kaiserslautern , cranes were supplied by the Nuremberg machine works Wilhelm Spaeth and the Würzburg company Georg Noell & Co. , the pneumatic tube system was built by Alois Zettler , and other technical installations came from Siemens-Schuckertwerke . The costs for the main customs office amounted to 1,760,000 marks for the property and 8,170,500 marks for the buildings. The latter, however, includes the construction costs of 485,000 marks for the customs facilities at Munich South Station , which were built for the customs clearance of fruit and vegetables on the grounds of the Munich wholesale market . In addition, the costs for the land and development of the new forest yard in Haidhausen were included.

use

In the first years of the main customs office, the storage areas were far from being used, so parts were rented to Munich companies. During the First World War , large parts of the warehouse, the counter and inspection halls served as an auxiliary hospital . In 1919 a main customs office in Munich III was opened, which was again housed in the Bürkleinbau on Bayerstraße. The main customs office Munich I was only responsible for customs clearance in Munich without the Ostbahnhof, while all subordinate customs offices, customs inspections, tax offices and tax offices were divided between the two other main customs offices.

During the Second World War , the Wehrmacht used around a quarter of the warehouse space as a depot. The building was partially damaged by explosive bombs in air raids and the night before the US Army arrived, it was looted by the people of Munich. After the end of the war, the Americans used around two-thirds of the warehouse as a PX depot and converted it to suit their purposes. Many of the artistic and structural details were lost. Customs continued to work in the rest of the hall and in the administrative buildings. In 1963 ownership of the building was transferred from the Free State of Bavaria to the Federal Finance Administration , in 1969 the US Army gave up its use and the entire facility was again under German administration.

The main customs office has been a listed building since 1976 . From 1977 onwards, the Munich I Tax Building Authority undertook a partial renovation and reconstruction for around 28 million D-Marks, most of which were completed for the 75th anniversary of the building in 1987. Between 1994 and 2002 the former three main customs offices in Munich (West, Central and Airport) were merged, by 2007 the management and most of the departments gradually moved to the Sophienstrasse office at the Old Botanical Garden . Customs clearance in Landsberger Straße also ended after only mail had been processed in the end. The vacated rooms were taken over by the customs investigation department , the traffic control unit and, in 2004, by the financial control of illegal employment, which is why there is no longer public access to the building for security reasons.

The main customs office was also the filming location for television productions and event location: Christian Dior presented his autumn / winter collection 1999 in the counter hall, the dance studio of the ZDF Christmas series Anna was set up in the auditing room, two episodes of The Crimes of Professor Capellari and one of Siska were mainly filmed in the building. The main customs office was also used for the mini-series The Wish Tree . Until 1998, both the inventory of so-called German art from the time of National Socialism and looted art were kept in the main customs office . The Munich Oberfinanzdirektion (Oberfinanzdirektion) was responsible for works of art under federal administration that had been purchased by state collections during the Third Reich or illegally brought together from all over Europe and that were recorded by the Americans at the Central Collecting Point after the war . The fifth floor of the warehouse is now rented to the Deutsches Museum , which has outsourced parts of its depot there. Since 2015, the State Office for Monument Preservation has also had its depot for archaeological finds in the main customs office.

The building of the customs technical testing and teaching institute was completely renovated from 2011 to 2014 after the testing institute's laboratories moved into a new building near Munich Airport . Then customs offices and the Federal Agency for Real Estate Tasks were established in the offices . The attached residential buildings are rented by the Federal Agency for Real Estate Tasks, preferably to federal officials.

buildings

The main customs office is one of the major projects of the Prince Regent's time between 1886 and 1912. The major state buildings of the time, which were intended to illustrate “Bavaria's independence” and “the insistence on reservation rights” vis-à-vis the other countries in the unified German Empire since 1871, still shape the appearance of the City. They are characterized by a high standard of quality and contribute significantly to the fact that the cultural city of Munich, in addition to art, music, theater, literature and science, also in architecture at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries, the "high point of national and European importance" of Munich reached.

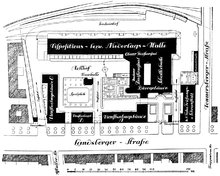

Around 40% of the approximately 35,000 m², roughly rectangular property was built over with a 14,000 m² area. The building complex comprises the administration building in the core of the site, the 180 m long warehouse building that adjoins it at right angles to the north and runs to the west, the customs technical examination and teaching institute in the east and three apartment blocks for employees on Landsberger Strasse in the south. It is laid out as a multi-wing complex with stepped buildings of different heights with several courtyards and green spaces, the street facade is closed by archways and walls, so that the complex gains "features of an independent work and living fortress". The construction of the facility in a uniform plan allowed the buildings to be optimally adapted to customs procedures and the separation of the flow of goods by arranging the buildings around several courtyards.

The Münchner Neuesten Nachrichten came to an end the day after the opening:

The whole building complex, “pleasing from the outside, functional on the inside and equipped with all the achievements of modern times, is a new ornament for Munich and shows how taste and usability, as well as comfort and technical perfection can go hand in hand with state buildings. And even if no merchant likes to pay customs, I almost believe that at least he will come to love the new building on Landsberger Strasse and will be happy to visit it.

architecture

The administrative building, the actual customs office, is oriented in a north-south direction and has a façade with a convex gable and clock tower. It is set back opposite Landsberger Straße and its entrance area is accessed through a courtyard of honor , which is formed and framed by the testing institute in the east and the side wing of one of the residential buildings. The front side of the building is formed by a transverse office wing, behind which the central counter hall is located. It is 35 m long, 14.5 m wide and extends over three floors with a height of 14 m. It is characterized by a barrel vault with huge frame trusses made of reinforced concrete. The ceiling surfaces are decorated with cassette-shaped stucco . The lower revision hall is located parallel to the counter hall, in between there is an atrium that extends to the basement and provides access for vehicles to the cellars via a ramp.

Behind the administration building, across it on the railroad tracks, is the camp wing. It has four main floors and, including the roof and basements, a total of nine floors with a total of around 30,000 m² of storage space. The ground floor was used for customs clearance, the upper floors were used as a bonded warehouse . Separate storage rooms were available for special types of goods: Flammable goods had their own small hall in the courtyard, vehicles were kept in a closed shelter, and there were separate storage areas for bad smelling goods at the end of the hall and a covered, but otherwise largely open veranda. Fats and oils as well as sparkling wine were stored in the basement. Rooms were also available for a veterinarian to examine the meat . In the eastern third, the dome of the 45 m high light shaft interrupts the massive gable roof. It towers over the ridge of the warehouse by 18 m and consists of an "elongated decagon that tapers in the shape of a dome to two ridge points." Its ribs with three entrances are considered to be the "prototype of the reinforced concrete framework". For weather protection, the concrete is clad with copper, which has a patina that was carefully restored during the renovation. The light shaft leading through all floors was previously open to the storage areas. After the renovations, mainly offices were set up on the warehouse floors, the light shaft towards these was largely closed.

The customs administration's technical testing and teaching institute to the east of the courtyard had office and business premises as well as several laboratories, as well as a central lecture hall with modern slide projectors and an extensive collection of samples. There was one laboratory for official examinations in general and for study purposes, another especially for beer and wine examinations, a practice laboratory for holding practical instructions for course participants in carrying out chemical examinations, a room for precision balances, a microscope room and a room for Burning tests in the cellar. In addition, three service apartments were set up in this building.

The four-story residential wing on Landsberger Strasse contained 47 apartments for employees of the customs office. Depending on their rank, they were staggered between seven rooms for the chief officer, four to five room apartments for customs inspectors and three room apartments for other officials, supervisors and machinists. All apartments had kitchens with gas stoves and central heating and were therefore of a first-class standard even for the simple employees. The upscale apartments had their own bathrooms and electricity. The courtyard between the residential buildings was green and equipped with a children's playground.

The different building heights and the many-sided structured roof landscapes with dormers and dwarf houses contribute to the overall impression of the complex . The research institute and the residential buildings have hipped roofs , the administration wing and the warehouse have a gable roof . The floor plans and structural forms are to be assigned to the reform architecture , the facades of all buildings are, in accordance with the late Art Nouveau , enriched with sculptural decorations made of shell limestone and bush hammered concrete . While the side facing the railway appears rather sober, “the appearance on the other sides is inviting and varied” and the administration and teaching areas are kept “representative”.

building technology

The authority's equipment used all the techniques of the time: Inside there were air humidification systems, as well as air dedusting filters and a device for fresh air supply. The controlled climate in the storage rooms was particularly important because the entire tobacco import from Greece into the German Reich was handled via Munich. The warehouse had a direct rail connection with a cable pull for moving wagons so that goods arriving by rail could be unloaded inside the customs office. Overhead cranes with a load capacity between 4 and 25 tons and four freight elevators with a permissible load of 1.5 tons each took care of the transport of the goods.

To avoid dust, the exhaust air was filtered from the examination rooms and the subsequent offices were kept under constant slight overpressure. Packaging and waste could be thrown from the two inspection rooms through shafts directly into airtight waste containers. Washrooms were set up in the basement for employees. A fountain basin was available in the Zollhof as a horse trough. For the electrical equipment, the customs office had its own transformer, which converted the electricity from the main station's electrical works to the required values. The two dispatch yards could be illuminated with arc lamps. All buildings had central heating or a district heating connection, there was an in-house telephone system, an electrical clock system controlled centrally from the head of the authority's office, and a pneumatic tube system .

Artistic equipment

The sculptures on the facades and inside the administration building were by Georg Albertshofer and Julius Seidler, as well as a portal sculpture by Wilhelm Riedisser . The vestibule and the counter hall received forged ornamental grilles, carved banister supports and counter fronts made of polished shell limestone. Other areas were decorated with wall decorations using stencil technology , which structured the walls with palmette friezes , pearl cords and coffers. Most of the furnishings have been preserved. Many doors and railings are original, a sculpture and several capitals have been preserved in the stairwell of the administration wing , the management office has the original wood paneling and furnishings.

Before the restoration between 1977 and 1987, cracks in the ceiling due to the effects of the war had to be professionally repaired in the counter hall before the plastered cassettes in the belt arches could be exposed and the stucco profiles and the stencil painting could be reconstructed based on paint residues and photos. The original front of an end wall made of shell limestone slabs and pillars was found and exposed under layers of plaster. Ornamental grilles were partly not preserved and had to be forged again according to photos. The former wooden fixtures in the plinth areas had been lost and no funds were available for reconstruction. Therefore, they were replaced by a painted base with a ridge pattern and a stenciled frieze over it, as originally existed in the adjacent hallways.

In the office belonging to the upper revision hall, the stencil painting was reconstructed by the church painter Peter Hippelein after finding paint residues under later overpainting and photos from the construction period. After consulting the State Office for the Preservation of Monuments , the impression that the glazing of the light shaft, which had meanwhile had been closed, was indicated by painted glass blocks. A series of cassette fillings in intense, fresh colors conveys the original character of an "upscale office".

Stucco and a ceiling fresco have been preserved in the vestibule. It shows the Patrona Bavariae surrounded by putti whose activities symbolize trade and thus the basis of customs. The cladding of the walls and columns made of shell limestone was lost, except for a small part. As part of the renovation, they were replaced by a paint similar to the lime slabs.

literature

- o. V .: The new customs buildings in Munich. In: Zentralblatt der Bauverwaltung , year 1912, issue 83 of October 12, 1912 and issue 84 of October 16, 1912

- N / A : The customs facilities on Landsberger Strasse in Munich . In: Der Industriebau , Volume 5, Issue 7 (July 15, 1914), pages 151–172

- Wolfgang Läpke: The main customs office on Landsberger Strasse . In: Monika Müller-Rieger (Ed.): Westend - From the Sendlinger Haid 'to the Munich district . Buchendorfer Verlag, 1995, ISBN 3-927984-29-9 , pages 111-123

- Bernd Raschert: Repair of the main customs office in Munich-West . Series of articles in Die Mappe - German painter's magazine, Callway Verlag, issues 7–9, 1987

- Siglinde Franke-Fuchs: 100 years of the customs office building at Landsberger Strasse 124, Munich . Main customs office in Munich, 2012

- Denis A. Chevalley, Timm Weski: State Capital Munich - Southwest (= Bavarian State Office for Monument Preservation [Hrsg.]: Monuments in Bavaria . Volume I.2 / 2 ). Karl M. Lipp Verlag, Munich 2004, ISBN 3-87490-584-5 , p. 375-377 .

Web links

- Bernd Raschert: On the building history of the main customs office in Munich-West. In: www.baufachinformation.de. Fraunhofer Information Center for Space and Building IRB in Stuttgart, accessed on July 4, 2011 .

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b Bavarian State Office for Monument Preservation: D-1-62-000-3763

- ↑ Läpke 1995, page 111

- ↑ a b Bernd Raschert: Repair of the main customs office in Munich-West . In: Die Mappe - Deutsche Malerzeitschrift , edition 7/87, page 9

- ^ Walter Wilhelm: Maut - Zoll 1834–1984 , Oberfinanzdirektion München 1984, page 9

- ^ Walter Wilhelm: Maut - Zoll 1834–1984 , Oberfinanzdirektion München 1984, page 22

- ^ Munich Yearbook 1901 , Carl Gerber, Munich 1901, pages 400, 448

- ^ Customs systems , industrial building 1914, page 154

- ^ O. V .: The new customs buildings on Landsbergerstrasse in Munich . In: Süddeutsche Bauzeitung , year 22 (1912), no. 44, pages 349–354, 350

- ↑ a b c Monuments in Bavaria, Munich-Southwest, half volume 2 pages 375–377

- ↑ a b Läpke 1995, page 112

- ↑ a b c New Customs Buildings , Zentralblatt 1912, issue 84, pages 542-544

- ↑ Franke-Fuchs 2012, page 13

- ^ Bernd Raschert: Repair of the main customs office in Munich-West. In: Die Mappe, Deutsche Malerzeitschrift , edition 7/1987, pages 9–12.

- ↑ Customs facilities. In: Der Industriebau , year 1914, page 172.

- ↑ Customs facilities. In: Der Industriebau , year 1914, page 171.

- ^ The reserve hospital D in the main customs office building on Landsbergerstrasse . In: Field medical supplement to the Münchner Medizinischen Wochenschrift , December 15, 1914, page 2395 f.

- ^ Münchener Jahrbuch 1919 , Carl Gerber, Munich 1919, pages 359, 422

- ^ Eduard Zitzelsberger: The night in the customs office . In: Marita Kraus (Ed.): Darkened Munich , Buchendorfer Verlag, 1995, ISBN 3-927984-41-8 , pages 196-200

- ^ A b Süddeutsche Zeitung: A magnificent building for customs officers , June 27, 2012, page R5

- ↑ Franke-Fuchs 2012, page 39

- ↑ Federal Office for Central Services and Unresolved Property Issues: Central Collecting Point ( Memento of the original dated January 22, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ A b c Martin Reindl: The main customs office - progressive technology behind historical facades . In: Friederike Meier, Serge Perouansky, Jürgen Stintzig (eds.): Das Westend - history and stories of a Munich district , StattPlan Verlag, Munich, 2005, ISBN 3-9801647-6-4 , pages 46-49

- ↑ Stephanie Gasteiger: Big move - Archaeological finds move to the main customs office in Munich . In: Bavarian State Office for Monument Preservation: Monument Preservation Information No. 160 (PDF; 9.8 MB), March 2015, pp. 35–38.

- ↑ Franke-Fuchs 2012, page 36 f.

- ↑ This classification is based on: Heinrich Habel: Munich - a development and cultural history overview . In: Heinrich Habel, Johannes Hallinger, Timm Weski: Landeshauptstadt München - Mitte (= Bavarian State Office for Monument Preservation [Hrsg.]: Monuments in Bavaria . Volume I.2 / 1 ). Karl M. Lipp Verlag, Munich 2009, ISBN 978-3-87490-586-2 . Volume 1, pages LIX – CXVI, LXXIV ff.

- ^ Habel, page LXXVI

- ^ Habel, page LXXVII

- ↑ Customs facilities , industrial building 1914, page 163

- ↑ Monuments in Bavaria, Munich-Southwest, half volume 2, page 376

- ↑ Customs new buildings , Zentralblatt 1912, issue 83, page 536

- ↑ Die neue Zollbauten In: General Anzeiger , supplement to the Münchner Latest News, July 2, 1912, page 1

- ^ Customs systems , industrial building 1914, page 165

- ^ Bavarian Architects and Engineers Association: Munich and its Buildings , F. Bruckmann, 1912 - reprint from 1978, ISBN 3-7654-1747-5 , pages 517-519

- ↑ inches new buildings , Zentralblatt 1912 Issue 83, Page 538

- ^ Bernd Raschert: Repair of the main customs office in Munich-West . In: Die Mappe - Deutsche Malerzeitschrift , edition 9/87, page 17

- ^ O. V .: The new customs buildings on Landsbergerstrasse in Munich . In: Süddeutsche Bauzeitung year 22, no. 45, pages 357–361, 360

- ^ Customs systems , industrial building 1914, page 169

- ^ Bernd Raschert: Repair of the main customs office in Munich-West . In: Die Mappe - Deutsche Malerzeitschrift , edition 8/87, pages 15-18

- ↑ Läpke 1995, page 121

- ^ Bernd Raschert: Repair of the main customs office in Munich-West . In: Die Mappe - Deutsche Malerzeitschrift , edition 7/87, page 11

- ^ Bernd Raschert: Repair of the main customs office in Munich-West . In: Die Mappe - Deutsche Malerzeitschrift , edition 9/87, pages 15-18

Coordinates: 48 ° 8 ′ 28.4 " N , 11 ° 31 ′ 57.7" E