Jedediah Smith

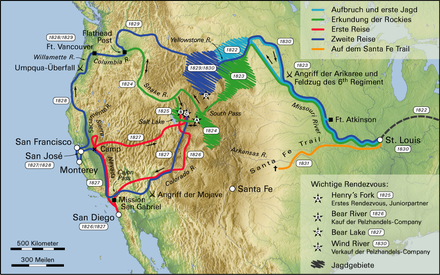

Jedediah Strong Smith (* probably June 24, 1798 in Bainbridge , Chenango County , New York ; † May 27, 1831 on the Cimarron River , south of Ulysses , Kansas , on the journey between St. Louis and Santa Fe) was an American trapper , Explorer and fur trader who is considered one of the most important mountain men in the American West . He was the first white man to explore the overland route from the Rocky Mountainsthrough the Mojave Desert to California and was also the first white man to cross the mountains of the California coastline and reach Oregon from the south .

Origin and private matters

Unlike most of the pioneers in the American West, Jedediah Smith was not a first or second generation immigrant from Europe, but came from a family of early settlers. His father, who bore the same name, was from New Hampshire and was one of the first families to move to the Mohawk River valley in New York State at the end of the 18th century . Jedediah Strong Smith, the son, did not know the exact circumstances of his birth himself. Later biographers determined June 24, 1798, other sources point to the year 1799, perhaps January 6, 1799 and the Chenango Valley region or the place Jericho, now Bainbridge, New York. Jedediah was one of 14 children. He felt responsible for his family for life and was in close relationship with them.

The Smiths moved to Erie , Pennsylvania , shortly after Jedediah was born , where the boy was raised. In addition to primary school, Dr. Simons, a doctor from the neighborhood, taught the basics of an English upbringing and even a few bits of Latin . Smith stayed Dr. Simons had a lifelong bond, not least because one of his brothers later married the doctor's daughter. In one of his last letters, Jedediah Smith made testamentary dispositions and considered Dr. Simons right after his parents.

When the family later moved to Ashtabula , Ohio , the youth worked as a clerk on ships on the Great Lakes and the rivers of the American Midwest . A consignment note issued and received by him at the age of 14 for a shipload on Lake Erie shows that he achieved a position of trust very early on. Here he got to know traders from the French fur trading companies who commuted between the headquarters in Montreal and the Indian regions of the west. They spoke to his sense of adventure as much as they gave him a role model for financial success. This time is considered to be the root of his interest in the fur trade and exploration of the West. As a young adult, Smith joined a Methodist church and, in contrast to most of his colleagues, was portrayed as a staunch Christian by contemporary witnesses and biographers.

From 1822, when he was in St. Louis in the services of William Henry Ashley and Andrew Henry for their fur trading company Ashley & Henry (later Rocky Mountain Fur Company ) came, his life is precisely documented.

In the service of Ashley and Henry

St. Louis was the westernmost city in the United States at the time and was considered the edge of "civilization". The prairies on the other side of the Mississippi , known as the Great Plains , were largely pathless, the rivers the only traffic routes explored. All of the Mississippi's western tributaries came from the Rocky Mountains . While the northern parts of the Rockies on Canadian territory were comparatively well explored by English fur hunters of the Hudson's Bay Company , the Rocky Mountains south of the (later) Canadian border were hardly known, and only small groups of trappers hunted on the upper Missouri River .

St. Louis fur traders William Ashley and Andrew Henry wanted to be the first to raise mountain hunting and outstrip their local rivals from the Missouri Fur Company . To do this, they put the following ad in the newspapers:

“To enterprising young men: I wish, I would like to say, ONE HUNDRED MEN who will ascend to the source of the Missouri River and be employed there for a year, two or three years.”

Published in the Missouri Republican and other newspapers in February and March 1822

Almost all men who were to shape the image of the trappers and fur traders in the next few decades - almost all mountain men who were to become symbolic figures for the early days of the Wild West - were among the participants in this expedition or their immediate successors. In addition to Jedediah Smith, now 23 years old, Jim Bridger , James Clyman, Tom Fitzpatrick , Hugh Glass , Edward Rose, David Jackson and the brothers William and Milton Sublette signed . Smith was hired as a hunter. The group embarked on May 8th with two keelboats and sailed up the Missouri River.

At the Arikaree , at the mouth of the Grand River , the group split up. Some of them, led by Henry, took the boats to the mouth of the Yellowstone River , while the rest with Ashley bought horses from the Indians and cut the great loop of the Missouri by land. Smith rode with Ashley and stayed at the mouth of the Yellowstone River when Ashley returned to St. Louis with last season's skins. From the base, Smith and colleagues went hunting along the Yellowstone. He spent the winter of 1822/23 in an outpost near the mouth of the Musselshell River .

Fights of 1823

It is believed that Smith was the hunter who went down the Missouri alone in the spring of 1823 to ask Ashley to get more horses after Indians from the Assiniboine had stolen most of the animals, and he went up the river again in the scheduled supply boats.

On June 3, the Arikaree attacked the small group of trappers and their boats. In the weeks before, a long-standing conflict between the Arikaree and the Lakota had spilled over into the never quite tension-free relationship with the whites when Arikaree met a group of fur traders from the Missouri Fur Company who had hired two Lakota as leaders. The Arikaree demanded the surrender of their enemies, and when the whites refused, a fight ensued in which two Arikaree were killed.

Ashley and the trappers were aware of the incident and took special precautions on their way through the Arikaree area and purchasing the horses. Their boats anchored in the middle of the river and only the last night some of the trappers spent with the horses on the bank. Despite all caution, the Arikaree attacked at dawn and inflicted heavy losses on the whites with the first attack. Thirteen trappers were dead, ten or eleven seriously wounded and Jedediah Smith, who had been one of the men on land, swam out to the boats as the last survivor and saved the life of the injured David Jackson.

The boats with the survivors retreated a little further downstream, the seriously injured were taken under the direction of Smith in one of the boats 450 miles to Fort Atkinson and on to St. Louis. They reached Fort Atkinson on June 18 and reported the events upstream to Colonel Leavenworth. Just a few hours later, a messenger arrived reporting another massacre by the Arikaree of Missouri Fur Company hunters on the upper reaches of the Yellowstone River. Leavenworth and all six companies of the US Army's Sixth Regiment , together a little over 250 men with two small six-pounder cannons and three keelboats, set out on June 22nd. Sixty white trappers moved with them, and the army provided them with a small 5.5-inch howitzer . A little over 200 warriors from various groups of the Lakota joined them to support the struggle of the whites against the warring people of the Arikaree. Jedediah Smith led one of the two groups the trappers had been divided into. The small campaign was the US Army's first military action against Indians west of the Mississippi.

The attack on August 10 was disappointing, the cannons had been placed in the wrong places and could not reach the villages. A cavalry attack against the stockade of the village was ineffective. Offers from private troops and the Lakota to attack the small lowest village were initially turned down by Leavenworth; later the plan did not materialize because it was no longer supported by the Lakota. They preferred to plunder the fields of the Arikaree and mutilate the corpses of their enemies from smaller skirmishes on the previous days.

Negotiations broke out that evening. The delegations agreed on the return of all firearms and other goods that the Arikaree had received as payment for the horses that were later slain, and the free passage of all whites on the river. All sides then smoked the peace pipe .

The losers were the Lakota. Together with the whites they had hoped to inflict a crushing defeat on the Arikaree and to gain rich booty in their villages. For the trappers it was achieved that their boats could navigate the river, but the campaign completely missed its further goal of impressing the Indians. Both the Lakota and the Arikaree believed the whites were weak and repeatedly attacked groups of hunters in the mountains in the years to come.

However, Smith distinguished himself in the events in such a way that from that point on he became a permanent captain (guide) of the trappers. In the following autumn he moved to the Absarokee (also called Crow) area. There, west of the Black Hills near the Powder River , he was attacked by a grizzly bear and injured in the chest and head. The bear had put Smith's head in its mouth and tore open the scalp from his left forehead, near the eye, to his right ear. The auricle was deeply torn several times by the teeth and almost completely separated. A companion stitched both the scalp and ear back together. Smith remained conscious the entire time and was able to ride back to camp on his own, where it took him ten days to recover. No report fails to state that from then on he wore his hair long to cover up his mutilated ear.

The South Pass

The hunting tour continued and the men met peaceful Cheyenne and Absarokee , with whom they inquired about beaver occurrences in this part of the Rocky Mountains. In February 1824, on the recommendation of the Indians, they moved over the South Pass to the upper reaches of the Green River and crossed the continental divide to the west. They weren't the first whites to take this route: in 1812 six members of the American Fur Company had already crossed the pass in the opposite direction, but since it was too far away from their hunting grounds and they could not use it, they wanted to keep it a secret from competitors . Your report was deliberately formulated so vaguely that the location and nature of the pass remained unknown. Smith rediscovered the pass and realized the importance of this wide and flat pass. The Rocky Mountains were not, as Lewis and Clark claimed in 1806 , an obstacle that could only be traversed on foot and without loads, but rather there was a relatively easy route into the unexplored land behind the mountains and ultimately to the Pacific Ocean .

Beyond the main ridge of the Rocky Mountains was the Oregon Country . After the British-American War of 1812 , the United States and Great Britain agreed to share it in 1818, but so far the British of the Hudson's Bay Company have used it almost alone. Americans had only advanced over the mountains on expeditions and in small groups and had left the beaver populations to the British.

In 1824, all of Ashley & Henry's famous men were active on the Green River. Smith, Jackson, Clyman, Fitzpatrick, the Sublettes and Bridger found abundant beaver populations and made the catches of their lives. From the Indians, they learned about life in the wild and the intricacies of successful beaver hunting. In June they all met on the upper reaches of the Sweetwater River , fetched supplies from a buried warehouse and celebrated the successful season. At the meeting they got the idea to turn it into a method of trading for the next year. In the fall, Smith moved northwest along the Snake River at its lower reaches and its confluence with the Columbia River , met Alexander Ross of the Hudson's Bay Company and accompanied him to the Flathead Post , where he met Peter Skene Ogden . From the two of them, Smith learned more about British operations in the Northwest.

In winter, Smith hunted alone in the beaver areas on the Great Salt Lake , which Jim Bridger had recently discovered, and collected 668 furs, an exceptional figure for a single man. Together, the company's men hunted skins weighing over 9,000 pounds that season.

The first rendezvous

In the early summer of 1825, Ashley called all of his men together at Henry's Fork , one of the tributaries of the Green River. At the first of the annual so-called rendezvous , the head of the trading company brought supplies for the next season into the mountains, supplied his trappers with barter goods for trading with the Indians, and received last year's furs to bring to St. Louis . Not only 91 hunters from their own company came, but also trappers from the English Hudson's Bay Company , who broke the contract and offered their skins to the Americans. The meetings quickly developed into large gatherings, at which Indians from the near and far area also arrived and offered their furs for exchange. They were "paid for" in diluted whiskey, glass beads, and colored textiles, and it was from this exploitation that the greatest profit arose. In addition, the rendezvous became orgy-like celebrations that played a major role in the spread of venereal diseases , especially syphilis , among the Mountain Men and the Indians.

William Ashley's partner Andrew Henry had retired from the arduous and risky business in the course of 1824 and Jedediah Smith was his natural successor as head of the hunters. At the end of the rendezvous, he joined the business as a junior partner and the company was now called Ashley & Smith .

independence

In the 1825-26 season, Smith moved his hunt further west. It was there that he probably first thought of expanding the business from the Rocky Mountains out into the plains and into the Pacific. In the surviving draft of a letter that was probably never sent, he was already speculating about the possibility of no longer transporting the skins from areas west of the Rocky Mountains to St. Louis, but of handling the trade from a port on the central Pacific coast.

After only two years with the new method of dating, Ashley had made so much profit that he too wanted to go out of business. Jedediah Smith remained a partner and increased his stake. Together with him, David Jackson and William Sublette took over the trading company at the meeting in the summer of 1826, which was now called Smith, Jackson & Sublette . The purchase price was quoted in the press as $ 30,000, payable over five years in cash or beaver pelts at five dollars each. Ashley remained attached to them, however, and continued to supply the company with supplies and barter goods. He went back into politics and was from 1831 to 1837 Member of the Missouri State in the US House of Representatives , was particularly involved in Indian issues and died in 1838, shortly after his retreat to St. Louis.

The expedition to the southwest 1826/27

The new shareholders shared their responsibilities: Sublette ran the St. Louis office and took care of the rendezvous, Jackson organized the hunt in the Rocky Mountains, and Smith had been commissioned by the shareholders to explore future hunting grounds. In August he and 14 men left the base on the Bear River , a tributary of the Great Salt Lake from the Wasatch Mountains , and moved over Utah Lake into the mountains. From here he moved in largely unknown terrain; Smith's account is the first to mention the mountains, rivers, and Indian peoples of much of southern Utah and its adjoining areas.

Smith and his men headed southwest, crossing several tributaries of the Green River east of the Wasatch Plateau. South of the plateau they encountered the valley of the Sevier River, which flowed in the "wrong direction" - to the northeast. Therefore they followed it only briefly upwards and reached the Escalante Plateau, named after a Spanish expedition from 1776. Through the desert region, they reached the Virgin River just below today's Zion National Park and followed it to the Colorado River . Here the Indians showed them a cave with thick salt deposits, an important discovery for the settlement of the region.

In November 1826 they met Indians from the Mohave people on the Colorado River and after months of traveling let themselves be distracted from their travel destination for a few days by their hospitality, the abundant supplies of corn, beans and pumpkin, and, according to the report, last but not least, the women .

Two Mohave volunteered to lead Smith and his people to the nearest Mexican settlement at the San Gabriel Arcángel Mission . To do this, they left the river at about the point where the state borders of Arizona , Nevada and California meet today , and moved directly west into the Mojave Desert and over the Cajon Pass into California, Mexico .

In California, Mexico

On November 27, 1826, Jedediah Smith and his 14 companions became the first whites to reach California and the Pacific Ocean from the Mississippi via the Missouri, the Rocky Mountains and through the deserts of the southwest.

They were warmly received by the monks of the San Gabriel Mission, from which today's San Gabriel near Los Angeles emerged . However, the two comandantes of the Mexican army were not at all pleased with the Americans and placed them under arrest. Like Zebulon Pike in 1807, almost twenty years later, the Mexican authorities treated the intruders as American spies. Through the mediation of an American captain from Boston , whose merchant ship happened to arrive at the same time as they were, Jedediah Smith, one of his companions and the captain William H. Cunningham were invited to San Diego to see Governor Jose-Maria Echeandía, who, after negotiations and queries in Mexico, was invited Seized cards and diaries and asked them to leave the country immediately. The request to be allowed to leave California to the north to explore the beaver areas there was refused. Smith was allowed to buy what he needed for the trip, but had to leave the country exactly the way he came.

The Americans only appeared to obey. As soon as they reached the hills, they rode north and disappeared into the wilderness of the Sierra Nevada . In the months of February to April they explored the western flank of the Sierra, encountered friendly and barely armed Indians and lush herds of elk , mule deer and pronghorn , but only a few beavers. At the height of the American River they tried to cross the Sierra in early May, but it was still winter in the mountains and they failed in the snow when five horses died of starvation. They withdrew into the valley of the Stanislaus River , a little further south, and set up permanent camp near what is now Oakdale .

Way back through the desert

On May 20, Smith tried again with only two companions, six horses and two mules packed with supplies and crossed the Sierra Nevada in just eight days, killing two of the horses and one mule. His route led over Ebbetts Pass, along the Walker River and south past Walker Lake . A valley there with about 1400 inhabitants is now called the Smith Valley . Jedediah Smith reported that there were 4 to 8 feet (1.20–2.40 m) of snow on the mountains.

To the east of the mountains lay the completely unknown desert of the Great Basin . By the end of May it was already largely dry and all game had left the area. The structure of the terrain with rugged rock ridges in north-south direction made crossing to the east particularly difficult. In addition, there are sand dunes on the route, which are difficult to move about, and sections of salt desert where there is even less drinkable water than elsewhere. It took Smith and his two companions twenty days to travel about 400 kilometers, of which they hiked several times for two days without water. The few Indians in the area were described by Smith as "the most wretched of the people who have neither clothing nor a means of subsistence other than grass seeds and locusts." On the other hand, the Paiute and Gosiute are said to have told generations later of the three half-dead, white men who emerged from nowhere in the salt desert, stumbled to a spring and stuck their heads in the water. They finally had to leave one of the two companions dying in the desert. But they found a spring a few miles further, Smith ran back with a kettle full of water and found the man still alive. Thanks to the water, he recovered enough that he and Smith reached the source. With only one horse and one mule left, the three arrived just in time for the rendezvous at Bear Lake , the other pack animals had died and had partly served them as food on the way. In a detailed letter to Superintendent William Clark of the Bureau of Indian Affairs , Smith described his trip, the areas explored and their residents. This letter in the US federal government archives is the most important source of the discoveries along with Smith's literary travelogue. In addition, fragmentary records of one of the men who remained in California, Harrison G. Rogers, and a few files from the Mexicans have survived.

The second voyage 1827/29

Immediately after the rendezvous, Smith left again. This time his tour group consisted of 19 men and they did not try to cross the desert of the Great Basin again, but bypassed it in the south along the Colorado and through the less hostile Mojave Desert. In mid-August they met again Mohave Indians, who had welcomed them in a friendly way the previous November. Smith and his men stayed with them for three days, building rafts to cross the Colorado with their gear. None of them knew that by now other fur hunters operating out of the Mexican Taos and presumably belonging to Etienne Provost had met in a violent conflict with the Mohave and that the Indians recognized Smith and his people as fur hunters as well.

During the crossing, when some of the men were already on the other bank, others were rowing on the raft and only a few remained, the Mohave attacked without warning. Smith and nine companions on the other bank survived, the other nine were killed and large parts of the equipment were lost. The ten left more of their luggage, as they had no horses or mules, and set off on foot. When they were pursued by the Mohave, they holed up in a thicket with just five rifles, killed two of the Indians and injured another. The Mohave broke off the chase; Smith and his people went into the desert on foot. In nine and a half days, or nights, because they only hiked at night because of the heat, they reached the area of a ranch that Smith had known from the previous year via the Cajon Pass. They were welcomed in a friendly manner and the rancher gave them horses and necessary equipment. Smith wrote a letter to the Fathers of San Gabriel and set off north with seven companions to the camp of his companions from the previous year on the Stanislaus River, where they arrived on September 18, 1827, just under four months after Smith had left camp. Two men voluntarily stayed in the south.

Back in California

In the meantime, the Mexicans had learned from the Christianized Indians that the hunters had not left the country in the south-east in the spring, but camped in the north. General Echeandía demanded that they either leave immediately to the east or report to San José , where they would be placed under arrest. When he learned that the leader Smith was no longer in the country, the pressure on the Americans eased, especially since they were difficult to reach in the completely remote region.

When Smith got back to his people, he and some companions went to San Jose to buy supplies and was arrested. A lieutenant came from the Presidio in San Francisco to question him on the allegation that the Americans were denying control of Mexico over the San Joaquin Valley and claiming it for the United States. Smith denied the allegation. One of the witnesses was an Indian who was Alcalde on the San Jose Mission. He had visited the white camp. His testimony was supported by one of the mission's priests.

Again the captains of two merchant ships stand up for Smith, who happened to be in the area, and Governor Echeandía, who now resided in Monterey , ordered Smith and the captains to stay with him. The governor gave him only the necessary time to provide himself and his people with equipment and supplies, and demanded that he leave immediately in a northerly direction, under no circumstances across the sea, nor east to the Mexican-claimed region south of the 42nd Latitude. Smith signed a liability statement on November 15, 1827, in which he agreed to pay a fine of $ 30,000 if he failed to comply with the agreement.

Camp on the Stanislaus River was canceled and Smith from Monterey and the men from the wild met in San Francisco. In town, they were able to sell their beaver pelts for almost $ 4,000, which made them generous in funding for their equipment. Thanks to the good financial resources and because he underestimated the difficulties of his travel route, Smith decided to enter the speculative trade in riding and pack animals. In addition to the 65 animals the men and their equipment were supposed to carry, he bought another 250 horses and mules for $ 10 each, which he hoped to bring to the Rocky Mountains and sell to the fur hunters there for $ 50.

They had since been joined by one of the two men who had stayed in Southern California in September. They were also joined by a young Englishman who happened to be in the region. On December 30th, the hunters finally set out, again in almost completely unknown territory.

The train to the north

There are different theories about their plans. Most likely, they intended to venture along the Sacramento River to its unexplored upper reaches and thence to the Pacific coast, work their way north to meet the Willamette River, known to them, which connects them to the Columbia River and the fur trading bases there. Other theses assume that Smith was hoping to find the legendary Buenaventura River , a fabulous river that would flow from the Rocky Mountains directly west to the Pacific and flow somewhere north of San Francisco Bay. Along the Buenaventura, they could have reached the company's rendezvous near the salt lake with relatively little effort.

The travel records do not reveal any closer exploration of the rivers in an east-west direction, suggesting that Smith, because of his good knowledge of the western Rocky Mountains, did not seriously believe in the legendary river, but expected to have to venture far north .

The group consisted of 20 men, experienced in the wilderness, and their leader Jedediah Smith was the most experienced of them, even if he was only 29 years old. They set out from San José and, because of the large fen areas, needed more than six weeks to travel around San Francisco Bay and the Sacramento-San Joaquin River Delta until they reached the east bank of the Sacramento River on February 12 stood a little south of today's California capital .

Sacramento River and Coast Mountains

For the next two months they moved along the east bank of the Sacramento River. They explored the flowing rivers and streams and went fur hunting. The beaver populations were not as abundant as in the Rocky Mountains, but interesting enough that the tour group made slow progress. They left the river on April 10, around what is now Red Bluff . The Sacramento forms extensive swamps here, which they could not cross with the many animals. Smith decided to cross the river and head north-west.

They climbed uphill along Cottonwood Creek , which was split into several arms , and when this too became too swampy, they moved in the same direction cross-country, crossing the ridge of the mountains in the area of the Klamath Mountains without first realizing it. On April 17th, they encountered the Trinity River , which flows north-west to the Pacific Ocean. No white man had ever entered this area or even crossed the mountain ranges.

The Trinity led them on and flowed into the Klamath River . Here they met Indians from the Hoopa and Yurok peoples again for the first time . Relations were peaceful, they were able to trade with the Indians and exchanged especially fish, but also beaver pelts for their glass beads and colorful ribbons.

The main problem for travelers was the dense forests. The area is now designated as a Redwood National Park because of the coastal redwoods and the forests of the temperate rainforest ecosystem . A portion is named Jedediah Smith Redwoods State Park after the first white man in the area . The 300 horses and mules were an enormous burden between the steep slopes and the dense tree population. Almost every day several were lost in the frequent fog, they could often be found again, but not always. Many animals fell on the rocky slopes, some to Death, others had to be killed because of broken bones. A few fell in Indian hunting pits. Almost every day the chronicle recorded losses. The group was also making slow progress. Between 1.5 and twelve miles (2.5 to 20 km) they estimated their daily progress, with an average of just under 6 miles (10 km).

The diary was kept here by Harrison G. Rogers, one of the few except Smith who could write. His records are particularly detailed, he paid attention to the landscape and the trees, recorded every encounter with Indians and noted the daily hunted booty. He correctly suspected that the rugged landscape owed its origin to earthquakes , even if he had no knowledge of the geology of Northern California or the principles of plate tectonics . He mentioned particularly thick trees, which he calls cedars , but did not notice that the coastal redwoods that only occur here were not only strikingly thick, but also the tallest trees in the world at over 100 meters.

On the Pacific coast

They reached the Pacific coast near the mouth of the Klamath River and moved north along this coast across what is now the border with the US state of Oregon . Here they rarely met Indians. They fed on the hunt and occasionally caught beavers again. On July 2, the men's contracts expired and Smith extended her tenure at the rate of one dollar a day until she reached the fur trading stations on the Columbia River. One of the hunters negotiated a fixed price of $ 200, but from the start in the Mexican area.

The coast was now too rugged, the group dodged a little inland and moved north there. Only after about 100 kilometers, on the Coquille River , did they come across Indians again, who mostly fled in panic when they saw them. At the river itself, Smith frightened a group so much that they abandoned their canoes and fled on foot. The travelers used the canoes to cross the wide mouth of the Coquille. The horses and mules were herded into the water and swam alongside.

To the north of Cape Arago they met again a small group of Indians who spoke Chinook Wawa , a newly developing pidgin language derived from the Chinook languages and used throughout the northwest as a lingua franca between Indians and white fur traders. They learned from them that they were only ten days' walk from areas regularly visited by Fort Vancouver fur traders . The end of their journey seemed near.

A few miles later, on July 10th, they encountered the southern tip of Coos Bay . They came to a village with around 100 Indians who called themselves Ka-Koosh . It could have been Coos or Kusan, possibly also Kuitsch, at least a people of the Yakonan language family. The houses in the village were sturdy and built from split planks, no longer simply from pieces of bark as in the southern neighbors.

At first they were able to trade successfully; one of the Chinook speakers served as the interpreter. They exchanged fish, berries and edible clams as well as beaver pelts and a few otter and sea otter pelts. A conflict later broke out: an Indian fired arrows at eight horses and mules, four of which he fatally hit. When the damage was noticed, the villagers fled into the woods. Only the two interpreters stayed and tried to explain that the killings were due to a single Indian who was dissatisfied with a deal. The mood was tense, because for the first time since the beginning of their journey the Indians lived in such large villages that the twenty whites felt vulnerable to the distinct superiority of the Indians despite their horses and weapons. Smith crossed the nearest river beyond the Indian village and made sure that there were always hunters on both banks to protect the caravan.

From the northern end of Coos Bay, an Indian accompanied them for two days' marches to the Umpqua . At the mouth of today's Umpqua River, they met again a large village with 70-80 inhabitants. They started a successful trade until they discovered an umpqua had stolen an ax. Before he could escape, the whites handcuffed him in front of the whole village. Smith and others threatened and interrogated him with their guns. When the ax found itself in the hiding place named by the prisoner, the mood relaxed a little.

The umpqua gave Smith a route recommendation. He should not stay on the coast, but pull the Umpqua River upstream, keep north and climb a range of hills. Behind it he would find the coast arm of the Willamette River , which would take them to known areas and eventually to Fort Vancouver. The distance to the coast arm should be only 15-20 miles. The description was correct, but the distance, even as the crow flies, is almost four times as great.

Early in the morning of July 13th, Smith and another man set out in a canoe to scout the trail along the Umpqua. On their return they found the camp destroyed and all the men slain. They immediately jumped back into the canoe and fled upriver, fought without any further equipment as they carried on the man for the little scouting trip through the planned route to the Willamette River and from there along the Willamette Valley to Fort Vancouver. Because of the much further distance than initially assumed, they did not arrive there until August 10th. To their surprise, they met another of their traveling companions there, Arthur Black, who had arrived two days earlier.

He had survived the first attack, shook off three Indians and fled into the bushes. When he saw that his comrades had no chance, he stayed in his hiding place and started walking north near the coast. Without any equipment, he lived on berries for a few days and finally asked the Tillamook Indians for help. They were in regular contact with the English fur hunters and traders, gave him food and took him to the base of the Hudson's Bay Company in Fort Vancouver.

At the Hudson's Bay Company

Fort Vancouver director, Doctor McLoughlin, and the leader of its fur traders, Alexander McLeod, were deeply concerned about what was going on, as the safety of their people depended on peaceful relations with the Indians. Smith demanded a campaign of revenge against the murderers, but could not prevail.

McLoughlin and McLeod played on their relationships with the peoples of the region. They gave generous rewards to the Indians who had helped Arthur Black and tried to clear up what was going on.

Various versions circulated about the course of events between Smith's departure and the Umpqua attack. The umpqua, who had been threatened the day before for stealing the ax, was a respected warrior and demanded immediate revenge for the offense suffered. But he was outvoted by a higher-ranking chief. Nevertheless, the mood in the village was heated. The Umpqua chief reported that Harrison Rogers had invited Indians from the Keliwatset tribes related to the Umpqua to the camp in Smith's absence . A sub-chief tried to mount one of the horses to learn the art of riding from the whites. He was threatened with a rifle by one of the hunters, which was the reason for the spontaneous fight. Black confirmed the attempt to ride, but denied the renewed threat to a high-ranking Indian.

In addition, the Umpqua argued that the Americans had identified themselves as the future masters of the country, who would oust the English from the region and attract trade with the Indians. It was not possible to determine whether this sentence was even liked or invented in order to turn the English against the Americans. When Smith heard of the statement, he believed it possible that the interpreters of the southern peoples wanted to boast of the power of the Americans against the Umpqua, he and the leaders of his group would not have made such a statement.

Two years later, Dr. McLoughlin another version that initially did not find its way into the official reports. Accordingly, not only Indians but also their wives would have been invited to the camp and Rogers would have tried to force an Indian woman into his tent. When her brother tried to defend her, Rogers knocked him down and that triggered the immediate attack. Smith found this version very unlikely, and earlier entries in Roger's travel diary indicate that he was not interested in sexual relations with Indian women.

As Smith and the other two survivors of his group set off with the men from the Hudson's Bay Company for the fall campaign, more news came in later in September. The Umpqua were very friendly to the English, put all the blame on the Keliwatset, and were willing to return Smith's horses and hides that had ended up with members of their people. In the course of the next few weeks further messages from different peoples and villages arrived. Whites' property had been scattered throughout the region, but relations with the English were so good that large parts of it could be recovered. A total of almost 700 skins from beavers, sea otters and otters, 39 horses and mules, 4 metal kettles, a large number of beaver traps and other equipment and, last but not least, large parts of the travel diary and maps that Smith had drawn himself were rescued until just before Christmas 1828. The Hudson's Bay Company did not accept any compensation from Smith for their efforts.

Smith had initially hoped to join the hunters of his own company in the Rocky Mountains quickly, despite the advanced season, but winter started early and he was stuck. The head of the Hudson's Bay Company , Governor George Simpson , who happened to be in Fort Vancouver and took a great interest in the fate of Smith and his people, made him a good offer for his rescued furs and horses, so that Smith suffered no financial disaster. So he decided to spend the winter in Fort Vancouver and not return until the next year.

The return

He finally set out in mid-March 1829 and reached the area around the Teton Range on a northern route as Lewis and Clark had used in 1806, presumably over the Lolo Pass , where he met a group of his own company. Smith, Jackson & Sublette had had a successful year in Smith's absence, with just over 100 hunters in small groups in the Rocky Mountains.

Jedediah Smith was given a warm welcome and spent the entire 1829 season hunting. The company's hunters continued to advance northwest this year, under his leadership, into an area where beaver populations had not been hunted on a large scale because the Blackfoot Indians were considered the most dangerous people in the west. Fighting could be avoided for most of the season, it wasn't until November that the Blackfoot attacked a small group of hunters and killed two men.

Smith spent the particularly harsh winter in an outpost camp on the Powder River. Smith's diaries from this period are full of melancholy remarks. He writes about the companions who died next to him and about his motives for moving into the wilderness anyway. In April, despite the attack the previous year, they continued the hunt in the core of the Blackfoot area. The rapid melting of the snow caused the rivers to swell, and on a southern tributary of the Yellowstone, Smith's hunters lost 30 horses and, what was worse, 300 beaver traps while crossing. It was just with luck that no man died.

Meanwhile in St. Louis the conditions of the fur trade had changed. Since 1826 had been only around the Great Lakes operating, cash-rich American Fur Company of John Jacob Astor its business territory expanded westward. She bought the Missouri Fur Company and the trading house Pratte & Co of the Couteaux family and penetrated from the upper reaches of the Missouri River into the Rocky Mountains. For the first time , there was competition for Smith, Jackson & Sublette .

At the rendezvous of 1830, east of the Wind River Range , the shareholders Jedediah Smith, David Jackson and William Sublette took stock: They had had several financially successful years and after this season could not only handle the last liabilities from the purchase of the company and the supply their hunters settle in the mountains, but had also made a considerable fortune. With the new competition, business would be much more difficult. On August 4, 1830, they sold their company, now called the Rocky Mountain Fur Company , to their colleagues Jim Bridger , Tom Fitzpatrick, Milton Sublette (William's brother), Henry Freab and Baptiste Gervais. The purchase price was $ 16,000, payable in cash by June 15, 1831, or in beaver pelts at $ 4.25 each. They also had the proceeds from the sale of this year's furs that they brought to St. Louis. The season finally grossed $ 84,500, the highest sum ever made by a St. Louis company.

St. Louis and Death on the Santa Fe Trail

At the age of 31 and a wealthy man with the proceeds from the sale, Smith returned to St. Louis. For about a year he lived as a retiree, working on his travel log with the aim of publishing it. His time in the mountains was over, the melancholy mood of last winter remained. A young Yankee named J. J. Warner, who had been recommended by a doctor to move to the West because of his weak constitution, visited Smith and then described him as follows:

Instead of finding a leather sock, I met a well-born, intelligent, and Christian-minded gentleman who curbed my youthful urge and joyous anticipation for the life of a trapper and mountain man by telling me that if I would go to the Rocky Mountains , the chances of finding death would be much higher than restoring my health, and if I escaped the former and attained the latter, it would be probable that I would be corrupted for all life that was not half-savage style. He said that he had been in the mountains for more than eight years and that he would not return.

Smith felt responsible for his family and planned for two of his brothers to finance a trade with the then Mexican Santa Fe . The business idea probably came from William Sublette, who had already worked in the Santa Fe trade for two years and wanted to enter the overland trade independently with the capital from the sale of the fur business.

Trade with northern Mexico was just on the rise, while the fur business was on its last legs. The beaver population had decreased significantly due to the heavy hunting, and when the whites penetrated into previously unknown areas of the Indians, conflicts arose more and more frequently. Bridger, Fitzpatrick and the other partners could only keep the company until 1834, after which it was no longer worthwhile. The overland trade is different: in the United States, many goods could be produced much cheaper or of better quality than was possible in Mexico. Imported goods from Spain could not compete in terms of price. Textiles came first.

Originally, Smith only wanted his two brothers to finance the trip and thus enable them to start their business life. But in the spring of 1831, William Sublette, David Jackson and Smith decided to found a joint company again and operate a wagon train to Santa Fe. Smith himself wrote that he wasn't so much interested in profit from the business as he must have seen Santa Fe for his book on the West.

They joined forces with other business people and manned a total of 22 covered wagons with 75 people. Ten of the cars belonged to Smith and his family, nine were provided by Jackson and Sublette, two were brought in by outsiders, and one small car was jointly financed by Smith, Jackson and Sublette. In this case, the rear axle could be detached and equipped with a small cannon. On April 10th they left St. Louis and on May 4th they reached Independence , the last place before the prairie .

Their equipment was excellent, but none of them knew exactly what the route known as the Santa Fe Trail was . Sublette did not know where to find the water points either, and so the journey became very difficult. In addition, the summer of 1831 was particularly hot and dry. One of the employed helpers was killed by Pawnees while hunting for pronghorns , otherwise they made good progress despite all the problems. Smith is described as the one who upheld morale and kept men motivated.

From the Arkansas River , at the height of the later Dodge City , they turned on the Cimarron Route to the southwest to the Cimarron River and through the desert of the same name . They hardly found any water, and once the humans and the oxen, as draft animals, had no opportunity to drink for two days. On May 27, Smith went on an exploratory ride on the dry northern arm of the Cimarron River south of what is now Ulysses in Kansas in search of a watering hole from which he never returned. His companions thought he was dead when he failed to meet them at the agreed meeting point and headed directly west without looking for Smith or waiting for him. On July 4, 1831, they arrived in Santa Fe and learned of the fate of Smith when, by chance, several Mexicans came to the city on the same day and wanted to sell his weapons, which they had exchanged from Comanches .

Several not exactly identical reports about the circumstances surrounding his death are said to go back to a questioning of the Comanches, but are probably only free adornment. According to this, Smith is said to have found clean water in an almost dry river bed and, while he was drinking and watering his horse, neglected observing the surroundings. The Comanches had come so close that he could no longer flee. As in every Wild West story, Smith shot the leader of the Indians and at least one more, but whether he himself died from spears, arrows or a bullet, different reports tell differently.

personality

Jedediah Smith is described by contemporaries and biographers as an exception among the Mountain Men . His education raised him from the group of colleagues. While most of them were unable to read and write, Smith regularly kept a diary and noted all the events of his hunting, trading, and exploration trips. In addition, the devout Methodist always carried a Bible with him and often weaved biblical quotations into conversations and his notes. At larger meetings he preached several times and led a common prayer. His religiosity among the Mountain Men, who were predominantly not interested in spiritual subjects, sometimes took on traits that biographers described as obsession . Smith's melancholy diary entries and letters are interpreted as an expression of oppressive guilt before God.

He was also different from most trappers in his appearance. He dressed predominantly European, only his Indian hunting shirt made of light leather he had in common with his colleagues, who had mostly adapted their clothes to Indian customs. At six feet tall, he attached great importance to cleanliness, bathed at every opportunity and carried a box with shaving utensils and a mirror with him in the wilderness. Only in emergencies did he refrain from shaving.

His contemporaries noticed Smith's manners and behavior towards the Indians. He never swore, did not smoke, drank alcohol infrequently and moderately, and while most trappers lived with Indian women, often several, there is no evidence of Smith's relationships with Indian women.

Publications

In 1840 a first attempt to publish an adaptation of Smith's travel record as a book failed for unknown reasons. Parts of the original records were lost in a fire in St. Louis. The manuscript about the voyage 1826/27 remained with William Ashley as the executor of Smith's will, fell into oblivion and was only found accidentally in Ashley's estate in 1967 and handed over to the Historical Society of Missouri . It was published by George Brooks in 1977. Harrison Dale had previously recognized the importance of Jedediah Smith and highlighted it in several books from 1918 onwards. Then Maurice Sullivan published the first monograph in 1934, followed by Harrison Dale in 1941 with his most extensive work on Smith. Both relied on surviving parts of the manuscript and the diaries of Smith, other participants in his travels, official reports and recollections of contemporaries. Based on these works, further biographies of Jedediah Smith emerged in the following years, among which the books by Dale L. Morgan are particularly noteworthy. This determined in 1954 how great the influence was that Smith's reports had on the state of cartography in the American West.

The originals of Smith's records are now in the Bancroft Library at the University of California at Berkeley , the Library at the University of the Pacific at Stockton, and in the archives of the Missouri Historical Society in St. Louis.

The life of Smith has also been filmed several times in recent times:

- Into the West , TV mini-series (12 episodes), 2005, produced by Steven Spielberg , Jedediah Smith is portrayed by Josh Brolin .

- Taming the Wild West: The Legend of Jedediah Smith , TV movie, 2005 for the History Channel , Sean Galuszka plays Jedediah Smith

importance

Smith's historical significance is multifaceted. As a trapper and fur hunter, he was one of the pioneers who ventured into the west and discovered new territory. In the first generation he was one of the few who expressed their experiences in their own words. As a fur trader, he headed what was at times the most important American company in its most successful phase, during which it was able to keep up with the English Hudson's Bay Company , he helped develop the rendezvous method, built up the trade with the Indians in the Rocky Mountains, and was the first white man to explore large areas of the then still Mexican, later American West and became a wealthy man before he turned to the next promising business area.

His immediate influence was probably greatest in cartography . Before Smith crossed the Rocky Mountains, the west was a white spot between the English area on the Columbia River and the first Spanish, then Mexican south . The mountains were considered impassable, the rivers were unknown and even in the Pacific, since the first seafarers, explorers had only gone ashore at certain points because of the flat coasts. Smith carried the best available maps of his time with him, but they turned out to be largely speculative and completely useless for orientation. That is why he drew his maps himself. Almost every day he entered rivers, individual mountains and mountain ranges, deserts, lakes, bays and other features on the maps he brought with him. With the records rescued from the Umpqua Raid, Smith and Jackson began to draw up a map of all the areas they visited upon their return. Smith readily made his findings available to other cartographers, and so a few years later there were reliable maps of parts of the Rocky Mountains, the deserts of the west and southwest, and the coastal mountains from California to Oregon.

It is only more recently that Smith has been recognized for the literary quality of his travelogues, which are full of emotional accounts. Perhaps he was the one of the Mountain Men who sought the wilderness and the unknown the most and, at least in his depressive phases, realized exactly that he could not escape civilization, but even helped to spread it into the pristine areas.

Substantial criticism against Smith is alleged that although he made significant explorations with his expeditions to new hunting areas, he has not brought in any economic income since he became a partner and head of the company. He had more deaths in his trapper units than any other captain , was involved in the three most loss-making fights of all trappers with Indians with the attack of the Arikaree in 1823, the massacre of the Mohave in 1827 and the raid of the Umpqua in 1828, and he was the leader of the Trappers with two of them. This is not interpreted by Don Berry as a sign of incompetence, Smith's life was merely "under a bad star." Smith, Jackson & Sublette flourished through the trappers under the direction of David E. Jackson, who was the real "trapper." par excellence"

Quotes

- Regarding the goals of his first trip to the Southwest in 1826/27, Smith wrote that he wanted to find beaver areas on a par with those on the Missouri, but also: “I wanted to be the first to see a country without a white eye Man and follow the course of a river that flows through a new country. "

- When, in one of his early years in the Rocky Mountains, Smith reached a Blackfoot village who had never seen white men or horses before, the whole village panicked and a girl died of fright. Smith later recalled the incident as saying, "Could it be that we who call ourselves Christians are so terrifying brutes that we can literally scare poor savages to death?"

- In one of his melancholy periods in 1829, Smith wrote to his brother Ralph: “Being able to help those in need is why I face the dangers. It is the reason why I cross the mountains and the eternal snow. It is the reason I cross sandy plains in the summer heat, thirsting for water to cool my overheated body. It's why I travel for days without food, and I'm pretty happy when I can collect some roots or snails, and even happier when we can afford a piece of horse meat or a good roasted dog and above all else it is the reason why I deny myself the benefits of society and the pleasure of dealing with my friends! But I will add up all these joys when the Almighty Ruler grants me the privilege of being with my friends. Oh, my brother, let us answer to Him, the owner of all things, and give him a fair share that we owe him. "

Honors

After Jedediah Smith are named:

- Smith Valley , a sparsely populated valley in Nevada .

- Jedediah Smith Redwoods State Park in California , now part of Redwood National Park .

- the Smith River in northern California, the largest undeveloped river system in the state, and the Smith River National Recreation Area , a recreation area on the river that is specially developed for fishing.

- the Mount Jedediah Smith , a mountain in the Teton mountain range in Wyoming

- the Jedediah Smith Wilderness , a sanctuary in the Teton Mountain Range in Wyoming without any human intervention under the administration of the US Forest Service

- The Jedediah Smith Memorial Trail (also known as the American River Trail) is a hiking, horseback riding, and mountain biking trail that runs 30 miles (50 km) along the American River from Folsom Dam near Folsom to Sacramento in Northern California .

- the Jedediah Smith Society , an association for the study of the life of Smith, based at the University of the Pacific in Stockton , California.

A statue of Smith stands in front of City Hall in San Dimas , Los Angeles County, California.

In the films Night at the Museum , Night at Museum 2 and Night at Museum 3 , Owen Wilson plays Jedediah Smith.

literature

- Maurice S. Sullivan: The Travels of Jedediah Smith - a documentary outline including the journal of the great American pathfinder. The Fine Arts Press, Santa Ana 1934

- Maurice S. Sullivan: Jedediah Smith - Trader and Trail Breaker. Press of the Pioneers, New York 1936

- Harrison Clifford Dale: The explorations of William H. Ashley and Jedediah Smith - 1822-1829. Arthur H. Clark Company, Glendale 1941, Reprinted by University of Nebraska Press, 1991, ISBN 0-8032-6591-3

- Dale L. Morgan: Jedediah Smith and the Opening of the West. Bobbs-Merrill Publishing, Indianapolis 1953

- Dale L. Morgan, Carl I. Wheat: Jedediah Smith and His Maps of the American West. California Historical Society, San Francisco 1954

- Don Berry, A Majority of Scoundrels , New York, Harper & Brother, 1961

- George R. Brooks (Ed.): The Southwest Expedition of Jedediah Smith - His Personal Account of the Journey to California 1826-1827. Arthur H. Clark Company, Glendale 1977, ISBN 0-87062-123-8

- Dee Brown : The sun rose in the west. (Original title: The Westerners , translated by Kurt Heinrich Hansen) Hoffmann and Campe, Hamburg 1974, ISBN 3-455-00723-6

- Dietmar Kuegler: Freedom in the wilderness. Publisher for American Studies , Wyk 1989, ISBN 3-924696-33-0

Web links

- Jedediah Smith Society at the University of the Pacific, Stockton, California (English)

- Website about Smith of the American Studies Project at the University of Virginia

- Smith's Journal of the First Voyage (August 1826-July 1827)

- Smith's Journal of the Second Voyage (July 1827-July 1828 - incomplete)

Individual evidence

- ↑ HC Dale, p. 175

- ^ Kuegler, p. 96

- ↑ American National Biography, Vol. 20, 1999, Oxford University Press, New York and Oxford, ISBN 0-19-520635-5

- ↑ HC Dale, p. 175

- ↑ American National Biography

- ↑ HC Dale, p. 80

- ^ Edwin Thompson Denig, Five Indian Tribes of the Upper Missouri , University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, Oklahoma, 1961, p. 57

- ↑ Brown, p. 58

- ^ Kuegler, p. 98

- ↑ Brown, p. 61

- ↑ HC Dale, p. 181

- ↑ HC Dale, p. 164

- ↑ Brooks, p. 74

- ↑ Brooks, p. 123

- ↑ Brooks, p. 165

- ↑ quoted from HC Dale, p. 190

- ↑ Brown, p. 63

- ↑ Berry, p. 87

- ↑ James A. Sandos, Patricia B. Sandos: Early California Reconsidered - Mexicans, Anglos, and Indians at Mission San José . In: Pacific Historical Review , Vol. 83, No. 4 (November 2014), pp. 592-625, 612, 618

- ^ Thomas Frederick Howard, Sierra Crossing: First Roads to California , University of California Press, 1998, ISBN 0-520-22686-0 , p. 16

- ↑ HC Dale, pp. 242-276

- ↑ HC Dale, p. 249

- ↑ HC Dale, p. 270

- ↑ HC Dale, p. 272

- ↑ HC Dale, p. 275 with more precise information in a footnote

- ↑ HC Dale, pp. 280-282

- ↑ HC Dale, p. 284

- ↑ Brown, p. 66

- ↑ Berry, p. 235

- ↑ HC Dale, p. 296

- ^ Carl Hays, David E. Jackson , in: LeRoy R. Hafen (Ed.), The Mountain men and the fur trade of the Far West , Clark Co., Glendale, California, 1956-72, Vol. 9, pp. 223

- ↑ Memoirs by J. J. Warner, quoted from HC Dale, p. 299

- ↑ Brown, p. 69

- ↑ Brown, p. 69

- ↑ HC Dale, p. 308

- ↑ HC Dale, p. 310 f.

- ↑ Berry, p. 69

- ^ Kuegler, p. 97

- ↑ Hays, p. 224

- ^ Kuegler, p. 97

- ↑ Berry, p. 225 f.

- ↑ quoted from Brooks, p. 23

- ↑ quoted from Brown, p. 68

- ↑ quoted from HC Dale, p. 311 f.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Smith, Jedediah |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Smith, Jedediah Strong (full name); Smith, Jed |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | American trapper, explorer, fur trader |

| DATE OF BIRTH | around June 24, 1798 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Bainbridge |

| DATE OF DEATH | May 27, 1831 |

| PLACE OF DEATH | on the Cimarron River (Arkansas River) |