Jozef Tiso

Jozef Gašpar Tiso (pronunciation: Josef Tisso , born October 13, 1887 in Nagybiccse (today Bytča ), † April 18, 1947 in Bratislava ) was a Roman Catholic priest as well as a Czechoslovak and Slovak politician and party leader of the Ludaks . As their party leader, first prime minister and then president of the dictator ruled Slovak State collaborated He 1939-1945 with Nazi Germany .

Coming from a lower middle-class Slovak family, Tiso was sent by the diocese of Nitra in 1906 as a talented graduate of the diocese's Piarist high school to study theology at the Pazmaneum in Vienna . There he was ordained a priest in 1910 and obtained his doctorate in 1911 . After a brief war mission as a military chaplain on the Eastern Front and in Slovenia during the First World War , Tiso was appointed theology professor at the Piarist High School in Nitra in 1915 by the Nitra bishop .

After the Second World War , Tiso was arrested by American units in Altötting, Bavaria, and extradited to Czechoslovakia, where he was sentenced to death by a people's court in Bratislava after a controversial trial as a war criminal . On April 18, 1947, Tiso was hanged in Bratislava .

Life

Origin and youth (1887–1906)

Jozef Gašpar Tiso was born on October 13, 1887, the second of seven children in the town of Veľká Bytča (Hungarian Nagybiccse , now part of Bytča ) with around 3,000 inhabitants . Since the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867, the city belonged to Trenčín County in Upper Hungary , a provincial outskirts of the Hungarian kingdom with a majority of Slovak and Roman Catholic populations. The majority of the Slovaks were illiterate farmers and smallholders or city dwellers belonging to the lower middle class, with the more educated tending towards Magyarization . In Veľká Bytča itself, where the Slovaks made up two-thirds of the city's population, the Hungarians dominated the administration, the Germans the industry and the Jews dominated the trade.

Tiso's father Jozef Gašpar Tiso (1862–1943) came from a wealthy farming family and was a butcher with his own butcher's shop, which made him part of the lower middle class from a sociological perspective. His mother Terézia Tisová (nee Budíšková ; 1863-1947) came from less wealthy potters. Both parents spoke Slovak and reportedly did not speak Hungarian. Tiso's older brother Pavol took over the business from his father, the younger Ján became a priest. According to the set standards of their milieu, his four sisters were also successful in marrying in well. Tiso and his siblings were raised strictly Catholic by their parents. His maternal grandfather was the parishioner of her church, where young Tiso served as an altar boy. For their son, the parents soon considered the chance of a priestly career. Therefore, after completing four years of local elementary school, where he received his only formal instruction in the Slovak language, they sent young Tiso to the lower grammar school in Žilina ( Zsolna in Hungarian ) a few kilometers away . During his high school days in the much more Magyarized city, Tiso emerged as a particularly linguistically gifted student (Hungarian, German, Latin) and was only considered to lag behind when it came to physical education. In his class, Tiso was only surpassed by one Jewish student. In Žilina Jews made up about 20 percent of the total population and, like elsewhere in Hungary, excelled in education - they also made up about half of the students in Tiso's class.

After graduating, Tiso went to the higher piaristic grammar school and preparatory seminar in Nitra (Hungarian Nyitra ) in 1902 . Nitra was the basis of a key instrument of the Hungarian government's Magyarization policy: the Upper Hungarian Educational Association (FEMKE for short), which successfully promoted Magyar culture through educational projects. According to the Hungarian state ideology, the Slovaks were viewed as Magyars who simply spoke a different language. Slovak schools and cultural associations have been closed by the government, teachers with insufficient knowledge of Hungarian have been threatened with dismissal, and non-Magyar national activists have been detained. In Nitra, Tiso began to use the Hungarian language not only in class, but also with his classmates and in his spare time - from then on he also signed in Hungarian as Tiszó József . Tiso was one of the few students in Nitra with a scholarship . His grades in the final exams were excellent (third in the second year, best in class in the fourth year together with a classmate). Under the strict guidance of the preparatory seminar in Nitra, which was dedicated to “recruiting very young men for God's holy army” , Catholicism became Tiso's calling. The religious texts Spiritual Exercises of Ignatius of Loyola , in which the Jesuit founder emphasized military fervor and Catholic discipline, were formative for Tiso .

Studies and ordination in Vienna (1906–1911)

After his impressive graduation from the Nitra seminary, Tiso was sent by the Nitra bishop Imre Bende to study theology at the Pazmaneum in Vienna . Since the Diocese of Nitra usually nominated only one of the graduates, this was, according to historian James Mace Ward, "one of the highest honors that a local Catholic boy could receive" . The seminarians studying at this exclusive theological educational institution received their courses at the University of Vienna , but otherwise lived and learned within the Pazmaneum. This was considered a Hungarian institution: its graduates became clergy in the Hungarian, not in the Austrian church.

The Pazmaneum presented Tiso with a demanding program. Efforts were made to train conservative and ascetic theologians who focused on inner prayer and meditation . There was strict discipline: the seminarians got up at 5 a.m. every day, and spent a lot of time meditating in seclusion and listening to books read aloud. Tiso probably used the Imitation of Christ by Thomas von Kempen as the most important guide to this strict and pious life , a classic of the Devotio moderna from the 15th century, which placed spirituality over materialism. Tiso also fervently advocated priestly asceticism in his later life , and a copy of the Imitation of Christ was also among the few possessions that were given to his relatives after Tiso's execution.

At the university, in addition to intensive Bible study, Tiso also had courses in church history, law, philosophy and education. His theology courses included dogmatics , moral and pastoral theology , other courses dealt with pantheism , natural religion or church architecture. In addition, Tiso learned additional foreign language skills in Hebrew , Aramaic and Arabic and received instruction in exegesis , hermeneutics and homiletics . In addition to the various philosophical directions within Christianity, Tiso also had the opportunity to familiarize himself with the papal encyclicals , in particular Rerum Novarum , which represented a reaction of the Catholic Church to current social developments and committed the Church to social justice. Tisos Professor of Moral Theology Franz Martin Schindler - head of the theological faculty of the University of Vienna and theoretician of the Austrian Christian Social Party - had helped develop the encyclical, propagated Catholic social teaching and viewed the modern state as a means of Catholic corporatism . Schindler conducted his seminar together with his assistant, the later Austrian Chancellor Ignaz Seipel , who pursued Catholic goals with political realism. As a political priest, Tiso later also preferred realism, represented Catholic corporatism and Christian socialism , which suggests the influence of his professors.

A third formative Christian social figure for Tiso was the then mayor of Vienna, Karl Lueger . Lueger developed a new style of mass mobilization, and his anti-Semitism - although sometimes openly racist - tended to assert Catholic legitimation through denominational, social and economic justifications. In Vienna, Tiso also encountered strong trends in ultramontanism and Catholic integralism . The latter imagined the church in a death throes with modernity . Under his professor of dogmatics, Ernst Commer , the Summa theologica of Thomas Aquinas , whose philosophy was hierarchical , conservative and authoritarian , became Tiso's most important moral handbook as well as later political advisor. Tiso, who greatly admired Commer, later referred to him and Seipel as key figures influencing him. In Vienna Tiso also emerged as an excellent student. In his fourth year of college, Tiso was appointed Assistant Prefect of the Pazmaneum - the highest student authority. Even before he could reach the canonical age of ordination, he was ordained a priest with a dispensation in 1910. He achieved the rarely given evaluation of "excellent" for knowledge of the Bible and completed his studies with the best possible result. On October 15, 1910, the Science Council of the Pazmaneum Tisos accepted a doctoral thesis entitled "The Doctrine of the Immaculate Motherhood of the Virgin Mary in the Pre-Council of Nicaean Documents" . On 420 pages handwritten in Latin, Tiso analyzed the Greek and Latin literature from the first to the third century AD regarding this Catholic dogma, including the malaria in the catacombs . He obtained his doctorate in 1911 after completing two exams in dogmatics and moral and pastoral theology.

Career in Upper Hungary and First World War (1911–1918)

Between 1910 and 1914 Tiso worked as a chaplain in three different towns in Upper Hungary : Oščadnica (Hungarian Ócsad ) in the north-western mountains and the two south-western towns Rajec (Hungarian Rajecz ) and Bánovce nad Bebravou (Hungarian Bán ). The latter was the wealthiest and bourgeois, while Rajec was industrialized and Oščadnica was impoverished. All three cities had a predominantly Slovak and Roman Catholic population, with Bánovce nad Bebravou also having a sizeable German-speaking Jewish minority who dominated local trade. In 1910, only 4 percent of the working population in Upper Hungary belonged to the intelligentsia, while 70 percent of business people and bankers were Jews. Slovaks therefore often received their alcohol, commercial goods and loans from German, Hungarian or Galician Jews. In cities like Oščadnica, this pattern contributed to rampant anti-Semitism.

As a new priest, Tiso became a social activist. Although he spent most of his ten-month stay in Oščadnica studying for his doctoral examinations, he helped his superiors organize a farmers' union that sold goods such as footwear at lower prices than “the Jew” . In view of his activities in Rajec and Bánovce nad Bebravou, Tiso took over the leadership of a youth group and a Christian-Social Men's Association, in Bánovce nad Bebravou he also founded a Catholic group. The Rajec County sponsored lectures, balls and theater and Tiso instructed its members in Slovak business correspondence. Another area of Tiso's activism was alcoholism , on which he lectured. In 1913, Tiso published a series of anti-alcohol articles in the Slovak-language newspaper edition of the Hungarian People's Party Néppárt , in which he addressed the malevolent effects of alcohol consumption on the mind. In addition to human weakness, Tiso blamed the government parties and Jewish bar owners for the plague. While the parties manipulated the voters with alcohol, “the Jew” would quickly become rich by handling the poison and thus develop from a poor immigrant to a village master. In Rajec, where, as in many towns in Upper Hungary, there was a lack of credit institutions, Tiso was also involved in setting up a Slovak bank in 1912, which acted as a branch of a bank branch in Žilina and which advertised in well-known Slovak newspapers. In the middle of 1913 Tiso was transferred to Bánovce nad Bebravou.

The outbreak of World War I led to an acute breakdown in Tiso's social activism. Already in the reserve, the now 27-year-old Tiso was mobilized in Trenčín's 71st kuk infantry regiment. The lower ranks spoke mostly Slovak, the officers German. Tiso served as the unity chaplain. The regiment quickly joined the armies of the Central Powers on the Eastern Front in Galicia and got into heavy fighting in late August 1914. The 71st Regiment suffered appalling casualties, losing over two hundred soldiers and more than half of its officers in a matter of days. As a chaplain, Tiso worked near the line of fire and should address comforting and compassionate words to the wounded. In addition to the violence in battle, Tiso also experienced the civilian toll of the war. Tiso's later published notes show that his regiment was operating in Polish and Catholic areas. He expressed himself to the Poles with sympathy and compassion, he valued their piety and their appreciation for priests. He admired the Germans completely. He looked down on the Jews negatively: they are dirty, cause chaos and deceive. However, Tiso noted with a certain compassion that Jews were victims of pogroms . Tiso's military service was short, as he was diagnosed with a kidney infection in October and was called to the rear. This was followed by treatment via a sweat cure in Upper Hungary. Tiso then worked for a short time at a local garrison, but convinced his superiors to recall him in February 1915 for health reasons. In August 1915 he was reactivated by the army and transferred to the Slovenian regions, where the role of priests in organizing social and economic life made an impression on him.

After interventions by the Bishop of Nitra, Vilmos Batthyány, Tiso was finally discharged from military service and appointed by his bishop as professor of theology at the Piarist high school he had previously attended and as pastor of the seminary - a high-ranking diocesan position. This repositioning was favored by Tisos' war diaries published in a Nitra newspaper. In them Tiso presents himself as a nationally reliable idealist who defended the correctness of the Hungarian cause and praised the heroism of Hungary's soldiers. He typically celebrated the unity of the different peoples of Hungary. Tiso later admitted to having written the articles in order to gain approval from "Magyar circles" . This group also included the Nitra bishop Batthyány, who had a reputation as a Magyar chauvinist and would not have appointed Tiso as the pastor of the seminary if he considered him a Pan-Slav. In early 1918, Batthyány appointed Tiso as a diocesan librarian. In 1917, Tiso was also the local party secretary of the Nitraer Néppárt, the Hungarian Catholic People's Party. As a priest under the age of 30, Tiso joined the urban ecclesiastical and secular elite of Nitra.

Ask about Tiso's national identity before 1918

The only real black mark in Tiso's time in Vienna was a serious accusation in 1909, which, due to an exchange of letters with a friend in the Nitra seminary, brought Tiso close to Pan-Slavism or Slovak nationalism. The prorector of the Pazmaneum, however, stood up for Tiso as an exemplary student. The question of Tiso's national consciousness within Hungary was also raised later during his trial before the Czechoslovak People's Tribunal (1946–1947), who represented Tiso as a “Magyarone”, ie a largely Magyarized Slovak. Tiso biographers assume that he pragmatically did not want to endanger his career with his Slovak identity.

Tiso was well aware of his Slovak origins and indicated Slovak as the mother tongue when registering classes, which in Hungary was also the criterion of ethnicity in censuses. However, he always entered his name in the Hungarian form Tiszó . In the seminary he wrote sermons not only in Hungarian, but also in Slovak, as he was preparing for his pastoral work in the rural Slovak environment, where bilingualism was minimally necessary. He refreshed the Slovak language and identity every year during the summer holidays that he spent with his parents in Veľká Bytča.

Politician in Czechoslovakia (1918–1938)

MP, minister and theorist

Since 1925 he was an opposition member of the Slovak People's Party Hlinkas (HSĽS), which, together with the Slovak National Party, campaigned for the autonomy of Slovakia in the Czechoslovak parliament and rejected the Czechoslovakism propagated by Prague . When party leader Hlinka made a month-long trip to the USA in 1927, Tiso was briefly entrusted with the leadership of the party. While Hlinka was absent, Tiso agreed that the party would join the Czechoslovak central government. During the period of his party's temporary participation in government from 1927 to 1929, he was Minister of Health and Sports in Czechoslovakia.

In 1929 Tiso moved up to become the quasi-leader of the conservative party wing. Andrej Hlinka accepted him as deputy party chairman in 1930. In the same year Tiso published a small brochure: The Ideology of the Slovak People's Party , in which he presented the program of his party as a whole. In this publication, Tiso primarily defended the positive meaning of Slovak autonomy for Czechoslovakia. According to the Slovak historian Ivan Kamenec , Tiso's main ideological theme in the 1930s was always the problem of Slovakia's autonomy within Czechoslovakia from the aspect of the relationship of the Slovak people to the Czechoslovak state. He explained that the demand for autonomy does not arise from any political speculation, but from the natural law of the people, and it is therefore an inescapable basis for the cultural and economic strengthening of Slovakia. From this point in time at the latest, he was considered the party's chief ideologist. He took over the keynote speeches at party conventions and played a decisive role in shaping opinion in Slovakia through his journalistic activities. After Vojtech Tuka's conviction for treason in 1929, Tiso was able to expand his influence on Hlinka, which resulted in a certain degree of objectification and democratization of the party. It was not until 1936 that his influence on Hlinka was steadily narrowed again by the Nástupists (the political students Vojtech Tukas) and Karol Sidor .

In 1933, Tiso gave a speech in the National Council in which he described the global economic crisis as a crisis of "spiritual origin" . He condemned the state budget, which he described as "fictitious", and the new tax burdens it contained on the "people who were already financially exhausted". In his speech he also condemned the ideologies of liberalism and socialism and described communist and fascist terror as their consequences. On the other hand, he committed himself to the papal social encyclical Quadragesimo anno and its idea of a corporate state. In 1935 there was a falling out between Tiso and Karol Sidor after President Masaryk had resigned from his office and the votes of the HSĽS MPs decided on the new president. While Sidor favored the candidate of the Czechoslovak Agrarian Party, Bohumil Němec , Tiso supported the previous foreign minister and convinced Czechoslovakist Edvard Beneš . Tiso believed that he could negotiate Slovak autonomy with him too. In the end, Tiso prevailed and, thanks to his support, Beneš became the new President of Czechoslovakia. Like Andrej Hlinka, Tiso was basically in favor of a common state of Slovaks and Czechs, but on the condition that the Slovaks were recognized as an independent nation separate from the Czechs and equivalent to them. This is how Tiso formulated his party's position on the Slovak question in 1935:

“We are by no means reluctant to cooperate with the government with the aim of solving the Slovak question […] But we emphasize, and most emphatically, that a great principle must be applied in this cooperation: like with like, the Slovak one Nation with the Czech nation. Those who honestly stand up for the preservation of the Czechoslovak state must be consistent and sincere in order to strengthen the two pillars of this state, the Czech nation and the Slovak nation. "

Struggle for influence on Hlinka

At the party congress in 1936, Karol Sidor was able to unite the majority of the party behind him, as Beneš continued to insist on a concept of Czechoslovak unity even after his election as Czechoslovak state president .

Politician in autonomous Slovakia (1938–1939)

From the Munich Agreement to the Silein Agreement

After Andrej Hlinka's death in August 1938, Jozef Tiso, as Hlinka's previous deputy, became de facto party leader of the Slovak People's Party (officially only on September 30, 1939). After the Munich Agreement , as a result of which Czechoslovakia had to cede the Sudetenland to Germany, Beneš's resignation on October 5, 1938, created a political vacuum. In the Czech part of the country all bourgeois parties united under Rudolf Beran's leadership to form the Party of National Unity , which openly sought a one-party system on a national basis. In the Slovak part, at the invitation of the Slovak People's Party, deputies, senators and high-ranking officials from all parties met in Žilina on October 5 and 6, 1938 to negotiate a joint position on the demand for autonomy. However, the People's Party refused to negotiate with Social Democrats and Communists. The result of these negotiations were two documents. The first was the so-called Žilina Agreement , in which all bourgeois parties supported the People's Party's program of autonomy. The second was the Manifesto of the Slovak People , adopted by the Executive Committee of the People's Party. Above all, the manifesto emphasized the “indivisibility of Slovak soil”, which was intended to respond to Hungarian claims to southern Slovakia.

Prime Minister and establishment of the dictatorship

The Žilina Agreement recognized the Slovaks' right to self-determination and granted Slovakia extensive self-government. The central government in Prague accepted the proposal on the same day and appointed Tiso as Minister for the Administration of Slovakia . A day later, the central government appointed an autonomous Slovak provincial government headed by Jozef Tiso. As a result, Czechoslovakia was effectively transformed into a federal state, which from now on was called the Czecho-Slovak Republic. The Carpatho-Ukraine took under the leadership of the Greek-Catholic priest avgustyn voloshyn also an autonomous position in the new state structure. The new coalition government of the autonomous country Slovakia had five members:

- Prime Minister and Minister of the Interior: Jozef Tiso (HSĽS)

- Minister of Justice: Ferdinand Ďurčanský (HSĽS)

- Education Minister: Matúš Černák (Slovak National Party)

- Finance Minister: Pavol Teplanský (Agrarian Party)

- Transport Minister: Ján Lichner (Agrarian Party)

On October 9, 1938, a Czech-Slovak delegation, chaired by Tisos, and a Hungarian delegation met in Komárno to regulate the minority rights of Hungarians and a new border line. As a result of the First Vienna Arbitration , now dictated by the German and Italian sides , the whole of southern Slovakia was annexed to Hungary and, in addition to the majority of the Hungarian minority, 75,000 Slovaks were separated from Slovakia.

On November 8, 1938, after long negotiations, all important parties of the Slovak part of the country united with the HSĽS to form Hlinkas Slovak People's Party - Party of Slovak National Unity , HSĽS-SSNJ for short . The last party to join the alliance was the Slovak National Party on December 15.

In the elections in Carpatho-Ukraine on February 2, 1939, 92% of the voters confirmed Volozhyn in his office and the internal autonomy of Carpatho-Ukraine that he called for. Three weeks later, on February 23, the choice for Tisos HSĽS-SSNJ was even clearer with 98%. Fearing that the republic would collapse more quickly, President Hácha let Czech troops under General Prchala march into Carpathian Ukraine on March 6th. Avgustyn Volozhyn was deposed as prime minister and replaced by General Prchala. On March 10, Hácha also dismissed Jozef Tiso and with him three other Slovak ministers. The Slovak state parliament was dissolved and Bratislava was occupied by the Czech military. The leading pro-German politicians Vojtech Tuka, Alexander Mach and Matúš Černák were arrested, the deposed Transport Minister Ďurčanský managed to escape to Vienna.

Declaration of Slovak independence

On March 7th, Arthur Seyß-Inquart declared on a visit to Tiso that Hitler had decided to "break up" Czecho-Slovakia . Slovakia - according to Seyß-Inquart - should "use its unique opportunity and immediately declare its independence" . Tiso, however, insisted on aiming for independence in a peaceful way and at a given point in time, so that Seyss-Inquart left again.

After the occupation of Slovakia on March 9, 1939 by Czech troops (Homola Putsch), he was deposed by the Prague central government. Karol Sidor became the new head of the Slovak government on March 11th. Now Hitler sent high-ranking officials from the Foreign Office to Sidor and Tiso in order to win them over to the independence of Slovakia. However, this was rejected by both.

On March 10, after Tiso was deposed, the German agent Edmund Veesenmayer met Tiso to persuade him to telegraph the Fiihrer for help . However, Tiso refused and continued to adhere to the concept of a peaceful and evolutionary independence for Slovakia. Tiso later explained this rejection in an intimate circle on the grounds that once the Germans came here, we would no longer get rid of them easily .

The German government viewed the developments in Slovakia with unrest. Sidor refused to submit to German plans and to proclaim Slovakia's independence as quickly as possible. Tiso had also shown herself to be inaccessible.

At the instigation of Berlin, Ferdinand Ďurčanský insistently described in a letter to Tiso that the Czecho-Slovak Republic would definitely be destroyed and that Bratislava would have to take the German side in order not to snub Germany. Otherwise the occupation of Slovakia by Hungary would be expected. A little later, Tiso was officially invited to Berlin by SD agents to meet with Hitler.

Tiso hesitated at first and only accepted the invitation after he had received the approval of Karol Sidor's Slovak cabinet, the state parliament presidium and the party executive. However, Tiso was not authorized to declare binding obligations.

On March 13, Tiso was received with all military honors together with Ferdinand Ďurčanský and immediately brought to the German Reich Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop and then to Hitler. Tiso was told that Germany would in any case destroy the Czecho-Slovak Republic, but that Slovakia could first proclaim independence supported and guaranteed by the Third Reich. This - according to Hitler - must now take place at lightning speed . Otherwise Slovakia would be divided between Hungary and Poland. Tiso's argument that Slovakia was not sufficiently prepared for independence left Hitler and von Ribbentrop unimpressed. Eventually Tiso gave in, but declared that he had no authority to proclaim independence. Only the Slovak parliament could do this. Thereupon von Ribbentrop issued the ultimatum that the Slovak state parliament had to declare independence by March 14th at 12 noon. Otherwise Germany would lose interest in the further development of Slovakia.

While still in Berlin, Tiso applied to Prague to convene the Slovak state parliament for the next day, in accordance with the regulations. After informing Bratislava, he and Ďurčanský left Berlin after midnight in order to be in Slovakia on time the next morning. Shortly before the confidential session of Parliament, Tiso briefed Prime Minister Sidor and his cabinet.

As the first speaker, Sidor announced his resignation after briefly describing the events since March 9th. Then Tiso went to the lectern and reported on his conversations with Ribbentrop and Hitler. He left no doubt that only a declaration of independence could save Slovakia from Hungarian occupation. After a brief pause, the vote was taken without prior discussion. At 12:07 p.m., Slovakia's independence was unanimously decided. The then President of the Slovak Parliament Martin Sokol commented on the vote as follows:

“The Slovak parliament has not decided whether it is for the continued existence of the Czecho-Slovak Republic or not. Adolf Hitler had already decided on this beforehand. The question that we had to decide on was whether Slovakia should be annexed to Hungary or whether it should possibly be preserved as a whole and form an independent state. And the answer of the Slovak MPs to this question could not be other than the proclamation of the Slovak state. Out of sympathy or solidarity with the Czechs, we could not commit national suicide, but rather we had to draw such a political conclusion from the given situation that, in our opinion, best suited the interests of the Slovak nation. "

German translation:

“Our Slovak state was not born out of hatred, but out of a great love for independence and the staunch will to work for its ideal and to sacrifice oneself for it. This is how this thought should guide us. No hatred towards anyone, but a simmering love for its state that encourages us and enables us from day to day to work for our new Slovak state and to sacrifice ourselves for it.

What still needs to be removed from the set of the past, we will remove, but not with hatred, disturbing, rough or cruel, but in a Christian way. This applies equally to everyone. The [Slovak] government will put unnecessary Czechs in Prague anyway. This is not only a concern, but also the duty of the [Slovak] government and therefore no one should presume to solve this question independently.

The government will be at the height of its vocation and will resolve this issue, which is so important for all Slovaks, in such a way that not a single public interest, but also not the law and justice, will suffer. The same applies to the Jewish question.

The government already has a draft law ready and only recent events have prevented this draft from being passed by our parliament. Therefore any independent intervention in the solution of the Jewish question is unnecessary, impermissible and the government can and must intervene against every offender and punish him as severely as possible in accordance with the applicable regulations.

Our Slovak state was created through organized, creative and inspiring work for a better future for the Slovak people. Not only the Slovak government, but also every conscientious Slovak must regard as the main enemy of the Slovak people those who want to destroy existing values instead of creating new values through work, who want to bring about chaos instead of order and who do not revoke their untamed will, those who have to Make the government harmless before he can intervene and undermine the future of the Slovak people in their independent state with a thieving hand. "

Original text in Slovak:

"Náš slovenský štát nezrodil sa z nenávisti, ale z veľkej lásky k svojeti a odhodlanej vôle pracovať a obetovať za svoj ideál. Nech nás vedie všetkých predovšetkým táto myšlienka. Nie nenávisť oproti niekomu, ale vrelá láska k svojmu štátu, ktorá nás povzbudzuje a zo dňa na deň robí spôsobilými pracovať a obetovať za svoj nový slovenský štát.

Čo treba ešte z garnitúry minulosti odstrániť, odstránime, ale nie nenávistne, náruživo, hrubo a surovo, ale po kresťansky. Vzťahuje sa toto rovnako na všetkých. Zbytočných Čechov tak, ako tak bude vláda dávať k dispozícii Prahe. Toto je nielen starosťou, ale aj povinnosaťou vlády a preto nech si nikto nenárokuje, aby túto otázku i sám vybavoval. Vláda je a bude stáť na výške svojho poslania a vybaví túto, pre všetkých Slovákov tak dôležitú otázku spôsobom, aby netrpel ani náš verejný záujem, ale ani právo a spravodlivosť. Podobne sa má aj vec s otázkou židovskou.

Vláda už má pripravený návrh zákona o židovskej otázke a len posledné udalosti prekazili to, aby tento návrh bol našim snemom schválený. Preto akékoľvek samozvané zasahovanie do riešenia židovskej otázky je zbytočné, neprípustné a vláda bude vedieť a musieť proti komukoľvek čo najprísnejajšie zakročiťný potchaný a podľaa podľa.

Náš slovenský štát zrodil sa z organizovanej tvoriacej oduševnenej práce za lepšiu budúcnosť slovenského národa. Nielen slovenská vláda, ale každý povedomý Slovák musel by za úhlavného nepriateľa slovenského štátu pokladať Toho, kto by miesto tvorenia nových hodnôt prácou chcel NICIT už jestvujúce hodnoty, kto miesto poriadku chcel by vyvolávať zmätok a neskrotnú svoju volů neovládal, Toho by musela znemožniť skorej, než by kradmou rukou mohol siahať a podkopávať budúcnosť slovenského národa v svojom samostatnom slovenskom štáte. "

With the establishment of the independent Slovak Republic on March 14, 1939, Tiso first became Prime Minister and, from October 26, 1939, became President of the formally independent German vassal state . Also as president, he continued to be active as a Catholic pastor (pastor of the city of Bánovce nad Bebravou 1924–1945).

Politician in the Slovak State (1939–1945)

The struggle for the political character of the state

On October 26, 1939, Jozef Tiso was unanimously elected President of the State for a period of 7 years, whereupon the entire government and executive power passed to Vojtech Tuka as the previous Vice Prime Minister. The Slovak public reacted very positively to the election of Tiso as president. Poets even saw Tiso as the second head after the Great Moravian King Sventopluk . In the autumn of 1939 Tiso tried to introduce some aspects of the corporate state doctrine of Othmar Spann as part of an implementation law for the constitution with reference to the Catholic social encyclicals , but failed because of the objection of the German government. His insistence on a state governed by clerical corporations brought Tiso the displeasure of the Slovak National Socialists headed by Prime Minister Vojtech Tuka and the commander-in-chief of the Hlinka Guard Alexander Mach , who propagated a Slovak National Socialism . This led to ever greater internal party disputes between the clerical and corporate state-oriented (moderate) wing of the president and the Slovak fascists, who were mainly supported by the Hlinka Guard.

The conflict came to a head after Alexander Mach submitted his resignation to Tiso on February 21, 1940 as Commander-in-Chief of the Hlinka Guard and Head of the Propaganda Office in order to provoke German intervention. Tiso managed to at least postpone the "open government crisis" by not accepting Mach's resignation for the time being. It was not until three months later, when the Wehrmacht was on the western campaign , that Tiso accepted Mach's resignation on May 21, 1940. The new commander-in-chief of the Hlinka Guard was František Galan, a representative of Tiso's party wing. Galan immediately ordered the Hlinka Guard to be subordinate to the party organs of the HSĽS-SSNJ. In addition, all possible interference by the Hlinka Guard in the state apparatus was prohibited. The German leadership responded with the immediate dismissal of their ambassador Hans Bernard from Bratislava and warned Tiso through the Slovak ambassador in Berlin, Matúš Černák , against making any changes to the government.

In the so-called Salzburg dictate , Tiso then had to dismiss Ferdinand Ďurčanský , who had been reoriented to the Catholic-conservative wing of the party, from the government on July 28, 1940 . Its two ministries, the external and internal departments, were handed over to Tuka and Mach, respectively. Mach also became Commander-in-Chief of the Hlinka Guard again. The radical fascist wing of the Slovak People's Party, now strengthened by Hitler, soon began to tighten the existing anti-Semitic laws at high speed and to pass new, tougher laws. On September 9, 1941, the Slovak government then enacted the so-called Jewish code , one of the toughest and most anti-Semitic laws of all, based on the Nuremberg Laws .

In mid-November 1940, the open fight between the President Jozef Tiso and the ministers of his Catholic-conservative wing Jozef Sivák , Ferdinand Čatloš , Július Stano , Gejza Fritz , Gejza Medrický against the Slovak National Socialists Vojtech Tuka, Alexander Mach and Karol Murgaš began .

Against the now acute danger of Slovak National Socialism , which Tiso - despite all the willingness to collaborate in economic and foreign policy areas - condemned as a priest and patriot, he began to mobilize the party and the clergy on a common defensive front. When, as a result of Mussolini's failed invasion of Greece, the German Reich had to force its focus on the Balkans, Tiso was not only able to reject all of Tuka's proposals to reshuffle the government and parliament based on the German model, he even went into building an estates organization within The People's Party launched a counterattack shortly before the end of the year.

When at the turn of the year 1940/41 the German adviser for Jewish affairs in Bratislava, Dieter Wisliceny , was involved in putsch plans of the Hlinka Guard against President Tiso, Tiso's party wing tried to obtain Wisliceny's recall. When this did not succeed, Tiso began a systematic submission and disempowerment of the Hlinka Guard, which was consistently ruled by the radicals, under his control. From 1941 to 1943 the number of active guardsmen was also drastically reduced. While there were still 100,000 guardsmen in June 1939, their number fell to just 150 active members by the end of 1943.

In order to finally secure his position vis-à-vis the radicals and to regain control of the state, Tiso had himself raised to the status of “Vodca” (leader) in the party and state by imitating the German model by a law on October 23, 1942 . The law now granted the president the right to intervene in all state affairs and meant that the executive under Interior Minister Alexander Mach increasingly lost its independence and Mach lost his main leverage. Furthermore, after a rapid domestic political weakening, Vojtech Tukas, the head of the Central Economic Office Augustín Morávek, who was responsible for the Aryanizations taking place in Slovakia, was forced to resign in July 1942. Vojtech Tuka's resignation as deputy chairman of the HSĽS-SSNJ on January 12, 1943 marked the final victory of Tiso and his conservative-moderate party wing over the Slovak National Socialists.

Tiso knew how to combine his authoritarian Catholic attitude with some elements of the Nazi system that he liked, such as the Führer cult , the primacy of the party and the total coverage of the population, so skillfully that he appeared to the Reich leadership as a reliable administrator. Tiso did not spare lip service to the German Reich and in the spring of 1942 also supported the deportation of Slovak Jews to German camps in Poland, but otherwise he carefully avoided supporting totalitarian measures, the Prime Minister Vojtech Tuka and the Hlinka Guard based on the National Socialist model sought to realize.

Persecution of political opponents

According to the Slovak constitution of July 21, 1939, only three political parties were allowed in Slovakia according to the ethnic principle. Only the HSLS-SSNJ Jozef Tisos was approved for the Slovaks, Franz Karmasin's German party for the Germans and the United Hungarian Party of János Esterházy for the Hungarians . People outside these political parties have been persecuted and often imprisoned.

In the area of criminal law, however, the independent Slovakia largely followed the liberal legal order of Czechoslovakia. Legal repression did not play a central role in the persecution of political opponents either. Extrajudicial repression prevailed throughout the First Slovak Republic, and it increased over the years.

The two main repressive organs of the People's Party regime were the State Security Center ( Ústredňa štátnej bezpečnosti , ÚŠB for short ) and the Hlinka Guard (Hlinkova garda, HG for short). The police and gendarmerie carried out house searches in a de facto unregulated manner , controlled the population and were able to arrange whereabouts for “suspicious” people. The repressive organs were not even subordinate to state-administrative organs and could thus act outside of any control.

Immediately after the declaration of independence, hundreds of so-called "enemy" people were arrested by members of the Hlinka Guard. These were mainly exponents of the former government and left-wing parties. These people were detained in the Ilava Security Camp. According to Tatjana Tönsmeyer, at least 3,100 people passed through this camp between 1939 and 1945. She sees the climax of the political persecution in the period from 1939 to 1942, i.e. in the period in which the entire government and executive power lay with Prime Minister Tuka and the government. At the same time, Tönsmeyer states that the number of political prisoners imprisoned in Ilava in the period from 1943 to 1944, i.e. in the period in which Tiso once again had a decisive say in state enforcement powers as president and leader , had fallen compared to previous years .

The death penalty, on the other hand, was understood as an extraordinary punishment - although the penalties in Slovakia became increasingly severe during the war. The courts only passed this judgment in the absence of the accused. However, President Tiso always granted pardons to those sentenced to death, so that in Slovakia, as the only ally of the Axis powers, in fact not a single person was executed until 1944.

Only after the Slovak National Uprising in August 1944 did the situation change dramatically. During the uprising, captured partisans, resistance fighters, Jews and Roma were often liquidated by the Wehrmacht and by the readiness units of the Hlinka Guard (POHG for short) under the leadership of Otomar Kubala . From September 1, 1944, all Slovak security organs were then subordinated to a German commander of the security police and the security service in Slovakia . Since then, Nazi organs have been able to arrest Slovak citizens directly in Slovakia and deport them to the Sachsenhausen concentration camp and, from the beginning of 1945, to the Mauthausen concentration camp .

Role during the Slovak National Uprising

In December 1943, the bourgeois and Czechoslovak opposition signed an agreement with the communists on cooperation and preparation for an uprising. From 1944 onwards, the anti-German mood among broader sections of the population increased the closer the Red Army got to the Slovak border. The first partisan movements arose in central Slovakia in early May.

The functionaries of the Hlinka People's Party finally realized in the course of 1944 - which was also confirmed by developments on the Eastern Front - that National Socialism was sliding into a deep military and political crisis. According to Defense Minister Čatloš, Tiso refused to contact the Soviet Union or the Czechoslovak resistance groups. On the contrary, Tiso stressed his anti-Bolshevism at every opportunity.

On the evening of August 27, Slovak partisans arrived in Brezno and arrested members of the People's Party as well as a German officer. After they were loaded onto a truck, four Slovaks and the German officer were shot by the partisans and two other Slovaks were wounded.

Members of a German military commission were also murdered in the city of Martin . In particular, the Czechoslovak exile President Beneš put pressure on the rebels' military headquarters, led by Ján Golian. Beneš explained:

“It is the last moment that you wash off all that the Quisling government and so-called independent Slovakia have done to the Allies. At no cost let yourself be occupied without a fight! "

On the afternoon of August 28, the German envoy in Bratislava, Hanns Ludin, and the German plenipotentiary general in Slovakia, General Ritter von Hubicky , appeared before President Tiso to propose that German troops be deployed to combat partisans.

On August 29th, President Tiso gave his approval for German troops to enter Slovakia. The German ambassador in Bratislava, Hanns Ludin, testified before the People's Court in 1947 that Tiso was “seen to be able to come to this decision only after heavy internal struggles and in the recognition that the uprising would not destroy with the help of his own forces could be ". On the same day Jozef Turanec , who had been appointed Commander-in-Chief of the Slovak Army by Tiso on August 28, was arrested by partisans on his way from Bratislava to Bánska Bystrica. On August 30th, the commander-in-chief of the insurgents, Ján Golian , declared that Slovakia was at war with Germany and that the army was part of the Czechoslovak army in liberated territory. According to Slovak sources, more than 18,000 soldiers from the Slovak army and 7,000 partisans took part in the uprising in the first few days. As a result of the mobilization that began in the uprising area, 20,000 to 25,000 men were added.

On September 8, 1944, strong Soviet forces attacked together with the 1st Czechoslovak Army Corps in the direction of the Dukla Pass . On September 14th, the German SS-Obergruppenführer Gottlob Berger was replaced by Police General Hermann Höfle . On October 7th Brigadier General Ján Golian handed over the leadership of the insurgent army to General Rudolf Viest, who had flown in .

After two months, the uprising was suppressed by the German military, the SS and the Hlinka Guard standby units . On October 30, 1944, General Hermann Höfle organized a military parade in Bánska Bystrica in the presence of President Tiso and other top Slovak politicians, at which Tiso held a solemn mass and honored “deserving” SS men and publicly thanked Hitler.

Before the People's Court in 1947, Tiso declared that his thanksgiving to Hitler was part of his tactic to secure Hitler's favor, which the Slovak government seemed to have lost after the uprising.

Jewish question, anti-Semitism and the Holocaust

At the latest since the granting of autonomy, two Slovakian concepts for the “solution of the Jewish question” have formed in Slovakia, the conservative-moderate one by Jozef Tiso and Karol Sidor and the radical-fascist one by Vojtech Tuka and Alexander Mach. The representatives of the conservative-moderate line planned to reduce the share of Jewish citizens in the economy to 4% (which roughly corresponded to their share in the total population). The representatives of the radical-fascist line, on the other hand, wanted to see “the Jewish question” resolved as quickly as possible along the lines of Nazi Germany. Jozef Tiso justified his political line, which should initially only bring restrictions to the Jews in the field of work and business, mainly with economic arguments. Tiso explained his position on the Slovak Jews to foreign journalists in January 1939 as follows:

“The Jewish question will be resolved in such a way that the Jews in Slovakia will only be granted an influence that corresponds to their share in relation to the total population of Slovakia. The Slovaks will be trained in such a way that they can be fully active in economic and industrial life and can take over all those areas that were previously occupied by Jews. "

The so-called Sidor Committee formed the basis for the anti-Semitic laws of autonomous Slovakia . His task consisted in drafting the anti-Semitic laws and defining the term Jews. The first government decree regarding the definition of the term Jew came into force on April 18, 1939 in the already “independent” Slovakia. The feeling of the political leadership that, as a result of the First Vienna Arbitration Award, they had once again become a victim of outside control led to increased xenophobia, which favored a radical solution. Slovak anti-Semitism was radically reinforced when, shortly before the First Vienna Arbitration Award, some Jews from Bratislava demanded that Bratislava be annexed to the Kingdom of Hungary during a demonstration.

On November 4, 1938, the autonomous Tiso government ordered the deportation of 7,500 "dispossessed" Jews with Hungarian citizenship to the area to be ceded to Hungary after the First Vienna Arbitration. However, on December 8, 1938, the Slovak government authorities allowed the resettled Jews to return to their original locations. Tiso was initially not fundamentally hostile to the Jewish population, but pursued consistent economic anti-Semitism. For example, in his Christmas sermon of December 23, 1938, Tiso stated:

“And in the end the Slovak people also want to live in peace with the Jews, I would like to announce this very clearly and openly. The prerequisite for this peace, however, is that the Jewish elements are positioned in our society in such a way that they do not see themselves as alien elements, stand in the way or avoid each other. This includes not only the recognition of the rights of the Slovak people across the board, but also the correction of the representation of Jews in all areas of life according to their number. "

Two days after the proclamation of Slovak independence by the state parliament in Bratislava, Tiso told the representatives of the radical party wing:

"It will be the honorable task of our intelligentsia to prove that our state, even if it consists of different nations, can hold up and be a happy home for everyone."

When, in early October 1939, Tiso, while still in his role as Slovak interior minister, appointed six Jews to high state and economic functions, German agents reported to Berlin that if it stabilizes as a state, Slovakia will find itself in the most splendid Beneš system. Pastors, Jews and the newest breed, so-called “Neo-Aryans” (baptized Jews), whom the Catholic Church regards as Aryans of equal value, are in contact with the old Czechoslovakists and are developing a dedicated activity. On May 25, 1940, the German envoy in Bratislava, Hans Bernard, reported to Berlin that Hlinka Garden leader Alexander Mach was with the president and that Tiso was pushing for a radical solution to the Jewish question, which Tiso refused.

Despite the repeated anti-Jewish declarations and the adoption of a whole series of discriminatory laws, the National Socialist leadership, with Hitler at the helm, expressed dissatisfaction with the speed at which the Slovak Jewish question was resolved. When there was also dissatisfaction with the attempts by the Slovak government to achieve a foreign policy as autonomous as possible, Hitler decided to take radical action. During the negotiations in Salzburg in July 1940, he ordered Tiso to make fundamental changes to the Slovak government. The radicals within the People's Party now received the decisive enforcement powers.

One of the main representatives of the radical wing of the party, Alexander Mach, began in his function as Minister of the Interior to issue various statements that restricted the rights of Jews. So were z. For example, by decree, Jewish pupils are excluded from all types of school (with the exception of elementary schools). On September 1, 1940, Dieter Wisliceny arrived in Bratislava as a German "advisor for Jewish questions", who was supposed to prepare the basis for the later deportation of the Slovak Jews. On September 3, 1940, the Slovak parliament approved a government enabling law that gave the Prime Minister and the government formal responsibility for all anti-Jewish measures. The Prime Minister's ordinances, which could also be signed by the Interior Minister, thus gained the force of a law even without the approval of Parliament or the President.

Tiso publicly defended the new anti-Jewish direction within the framework of his authority as president and priest with Christian arguments, which caused disorientation and insecurity within the population. For example, on September 22, 1940, in a speech at a forum in Višnovce, he stated : “Allegedly we are taking away the businesses and trades from the Jews, and supposedly that is not Christian. I say: it is Christian because we only take what they [the Jews] have always taken from our people. ” Nevertheless, a document from the German military intelligence service of January 9, 1941 states that Tiso“ is still an effective one and rejects a targeted solution to the Jewish question. "

On September 10, 1941, Prime Minister Vojtech Tuka and Interior Minister Alexander Mach issued the so-called Jewish Code . Thereupon the Vatican envoy in Bratislava Giuseppe Burzio appealed to Tiso to at least make full use of the limited possibilities available to him to issue certificates of exemption. In mid-October 1941, the Slovak bishops also sent a protest memorandum to the Tuka government, in which they condemned its anti-Semitic legislation.

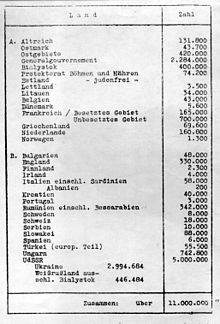

On December 2, 1941, Prime Minister Tuka, in secret negotiations with the German ambassador in Bratislava, Hanns Ludin , agreed to the forced relocation of Slovak Jews to German territory without the authorization of the Slovak government. Tuka did not inform the Slovak government of the planned deportations until March 3, 1942. Tiso initially offered no resistance to the subsequent deportations of Jews. In his Harvest Festival speech in August 1942 in Holíč , he declared in his harshest anti-Semitic speech that the Slovaks, because of the economic dominance of the Jews in the economy, would act in accordance with God's laws if they got rid of the “Jewish pest” and the Jews deported to the new state granted to them by Hitler in Poland.

The consent to deportation did not mean that the Slovak government consented to the murder of the Jews. It was assumed that the Jews would be settled in the east and obliged to work. The German Reich left the Slovaks in this belief and promoted the legend of the settlement of Jews in the Generalgouvernement . When members of the Slovak government were in Germany from October 23 to 24, Heinrich Himmler announced the plan that a place would be created in occupied Poland to which all European Jews would be resettled. In order to cover the "colonization costs" incurred by the simulated "settlement" of the Slovak Jews in the General Government, Prime Minister Tuka agreed to pay a "colonization fee" of 500 Reichsmarks for each deported Jew.

From March to August 1942 57,628 Slovak Jews were deported. However, a paragraph was added to the deportation law passed by the Slovak Parliament that exempted converted Jews who had converted to the Christian faith before March 14, 1939 and who were legally married to a non-Jewish partner from deportation. Similarly, Jews who had received a certificate of exemption from the President or one of the ministries could not be deported . The certificates of exemption also related to spouses, children and parents of those affected.

Thanks to the generous distribution of these certificates of exemption, a good third of the Slovak Jews were exempt from deportation and mass extermination. The fact that Tiso initially did not offer any resistance to the deportation of the expropriated Slovak Jews to the German “labor camps” during the first wave of deportations is shown by various sources, such as B. evidenced the German advisors to Jews. Hanns Ludin reported in a telegram to Berlin on April 6, 1942:

“The Slovak government has agreed to the evacuation of all Jews from Slovakia without German pressure. Even the President personally agreed to the evacuation, despite the step of the Slovak episcopate. The evacuation refers to all Jews who are specified as such in the Slovak Jewish Code. Jews who are outside the Jewish Code, that is, racial Jews who were baptized before 1938 and whose number is likely to be 2,000, are to be concentrated in camps in the country, according to the President of the Republic. The evacuation of the Jews is now ongoing without any particular incident. "

These deportations also influenced the attitude of the Vatican. In March 1942, the then bishop and later Cardinal Tardini spoke of the two madmen, Tuka and Tiso, whom he held responsible. But not only the persecution measures, their stop was also the action of the Slovak government. After the Vatican had repeatedly taken a stand against the deportations and had pointed out incorrect German information - not resettlement, but extermination of the Jews in Auschwitz, Majdanek and Lublin - the legal requirements for stopping the transports and internment were met on May 15, 1942 of the remaining Jews - insofar as they were not needed in the state apparatus - were created in the relatively humane Slovak concentration camps.

The deportations ended in autumn 1942, mainly because the remaining Jewish population was protected from deportations either in labor camps or by exemption certificates from the president or a minister (Ernest Žabkay, defender of Tisos before the Czechoslovak People's Court in 1947, declared that Tiso had all of them 9,000 such exemption certificates were issued to Jews and 36,000 Jews were saved from deportation. According to the latest findings of the Slovak historian Michal Schvarc, 828 Jews actually received presidential exemption papers. Since these also related to their families, around 4,000 Slovak Jews were under Tiso's presidential protection to have). The last transport train carrying Slovak Jews left on October 20, 1942. Until September 1944, Tiso steadfastly refused to accept any new deportations demanded by Berlin. This was made possible by the law of October 23, 1942, with which he was raised to the position of leader in party and state. As a result, he was able to regain the power of governance and enforcement that he had had to surrender to Prime Minister Tuka after his appointment as President in 1939. The German envoy Ludin describes the situation of the approximately 30,000 Jews who remained in Slovakia from autumn 1942 to autumn 1944 as follows:

“The economic situation of the Jews at large has improved in every way since 1943. Countless Jews were left in the factories, and most of them were newly hired. In many cases, the Jews are still the actual heads of "Aryanized" companies, the nominal owners of which - mostly members of Slovak political or state officials - lead a comfortable life with the money the Jews have earned and do not even think about joining them Incorporate companies. From such a standpoint it can be said that the Jews are 'economically indispensable'. "

Even after Hungary was occupied by the German army in May 1944 and the mass deportations of Hungarian Jews to German concentration camps began, the Slovak government refused to allow the deportation of Slovak Jews coordinated by Hanns Ludin. Indeed, Slovakia gave refuge to thousands of Jews who were hoping to avoid deportation to Hungary. The uncooperative attitude of the Slovak government in determining transport routes and its complaints about the treatment of the deported Hungarian Jews were criticized by the Hungarian government under Döme Sztójay and the German “representative in Hungary” Edmund Veesenmayer , as was the fact that the Slovakian Envoys in Budapest and the Slovak Ministry of the Interior called for Jews with valid Slovak citizenship to be released from the Hungarian internment camps.

Only after the suppression of the Slovak national uprising at the end of October 1944 and the occupation of Slovakia by the Wehrmacht were all exemption certificates for Slovak Jews that had been in effect until then. Mass executions by German units and the standby units of the Hlinka Guard were soon the order of the day. The new government set up on September 5, 1944 under Štefan Tiso , which had completely sunk into the vicarious agent of the German occupying power, could no longer develop any political initiative. Between September and December 1944, 2,257 people were executed. By the end of the war, between 1,000 and 1,500 people were killed by the German troops (although the proportion of Jews is unclear). From September 30, 1944 to March 31, 1945, a further 11,719 Jews were deported. Around 10,000 Jews were saved thanks to the help of the Slovak population.

Tiso himself made very negative comments about the Jewish population during and after the Slovak National Uprising. On November 8, 1944, Tiso responded to criticism from the Vatican - which accused him of inaction in the face of renewed anti-Jewish reprisals in Slovakia - with a letter in which Tiso, together with the Czechs, referred to the Jews collectively as enemies of the Slovak people . Nevertheless, at the beginning of October 1944, Tiso tried to ask Heinrich Himmler, who ultimately insisted on the deportation of all remaining Slovak Jews, to request the exception of all baptized Jews and those who lived in a mixed marriage with a Slovak partner in Bratislava. In his memoirs, which were summarized after his release from prison in 1968, the Minister of the Interior Mach, who was largely responsible for the deportation of the Slovak Jews, writes several times of President Tiso's interventions in favor of the Jews.

Foreign policy

Slovakia's political independence was severely restricted from the start. Slovakia was more closely tied to German hegemonic power than, for example, neighboring Hungary. In terms of foreign and military policy, this was primarily due to the protection treaty of March 1939 agreed with Germany. Slovakia also supplied mineral resources and approved the stationing of German troops along a strip of the former Slovak-Moravian border, the so-called "protection zone". The Slovak government put up stubborn resistance so that the protection zone statute - after Hitler had made major concessions to Tiso with regard to the military strength of the Slovak army - was only signed in August 1939.

On March 23, 1939, Hungarian troops attacked Slovakia from the Carpathian Ukraine, which they had occupied on March 15, without prior declaration of war. They were ordered to advance as far west as possible. The surprised Slovak troop units, which were supported by some Czech units still remaining in Slovakia, launched a counter-offensive on March 24th. On the evening of March 24, the Hungarian air force bombed the town of Spišská Nová Ves , killing 12 Slovaks and injuring 17.

After a ceasefire agreed on March 24, Prime Minister Tiso asked the Third Reich for military support through arms aid as part of the protection treaty. This was refused, but a direct intervention by German troops in Eastern Slovakia was offered, which Tiso refused. The fighting lasted until March 31st. After the end of the Slovak-Hungarian War , Slovakia had to sign a contract in Budapest on April 4, by which it had to cede a strip of land in the east of the country with 1697 km² and 69,930 inhabitants to Hungary. Slovakia had 22 soldiers and 36 civilians killed in this war.

Slovakia took part in the attack on Poland on September 1, 1939 . Only the military participation of Slovak troops in the attack on Poland ensured the existence of the "protective state" . Despite the strong polonophile currents in the Slovak population and occasional protests, Tiso, Defense Minister Ferdinand Čatloš and the then head of propaganda Alexander Mach granted the German insistence to participate in the attack on Poland, not least in expectation, thereby preventing further territorial separation to Hungary and that in autumn To be able to regain districts lost to Poland in 1938. Slovakia took part in the German invasion with a division .

In fact, for the participation of Slovak troops in the attack on Poland, Slovakia got back those areas that had been annexed by Poland after the Czechoslovak-Polish border war in 1920 and after the Munich Agreement in 1938. Hitler even offered Tiso the city of Zakopane and surrounding areas, but Tiso refused on the grounds that no Slovaks live in these areas and they never belonged to Slovakia .

Immediately after June 22, 1941, the government broke off relations with the Soviet Union and made three divisions with around 50,000 soldiers available for the war. The participation of the Slovak army in the war against the Soviet Union, which was demanded by the German Reich and which was absolutely unpopular among the Pan-Slavic-feeling Slovak population, was primarily associated with hopes of asserting territorial claims against Hungary by participating in the war. Tiso was determined to maintain Slovakia's contribution to the war on the Eastern Front in order to give Hitler a reason to protect Slovakia against Hungarian claims.

On December 12, 1941, Prime Minister Vojtech Tuka unilaterally declared that the Slovak Republic would enter a state of war on the basis of the three-power pact with the United States of America and the United Kingdom . As a result of this declaration of war, American and British planes bombed the capital Bratislava on June 16, 1944, killing between 300 and 770 people.

Relationship to National Socialism

Although Tiso belonged to the conservative-moderate wing of the Slovak People's Party, he was preferred to the radical Vojtech Tuka by the National Socialists as a "calm and well-considered personality", who had a high level of authority among the population due to his spiritual status. Hanns Ludin, Germany's envoy in Bratislava, underlined Tiso's preference two weeks after taking office:

"Without a doubt, Tiso is not only the first in terms of constitutional law, he is also the strongest personality in the country [...] I can't think of an equivalent substitute for Tiso."

But even if he did not reject an independent Slovak state in principle as the ultimate goal of a longer development, Tiso was reserved about the immediate independence of Slovakia in 1939 and was less pro-German than anti-Czech. In addition, Tiso was one of those who tried to curb the growing influence of the National Socialists on the politics and culture of the country. Although he repeatedly bowed to German demands, he said he only did so in order not to give Hitler an excuse to intervene in Slovakia.

Furthermore, Tiso was not interested in a racist restructuring of the Slovak legal system and only received his German advisor Hans Pehm once. He had criticized the corporate state ideas of the party leadership, as the national community never came into being . Tiso let him know that because of the power of religion and national sentiment, the Slovak nation could not be divided. Reservations towards Tiso came in particular from the security service of the Reichsführer SS (SD). In October 1943 an SD speaker declared:

“To regard the party (i.e. Hlinkas Slovak People's Party or Tiso and its supporters) as an internal political security factor must be described as absurd. The leading positions of the party are consistently filled with anti-German people. "

Above all, the elimination of the pro-National Socialist forces in the ranks of the Hlinka Guard, Catholicism, which was pushing its way into politics, and the signs of independent foreign policy activities soon met with resistance in Berlin. The stop of the deportations of Slovak Jews in October 1942 was also viewed by the German authorities as an act that left a very bad impression . The Germans of the Slovaks could never be as sure of themselves as they wanted, and although Slovakia looked like a puppet state on the outside, for some in Berlin it became evidence of what could happen if small peoples were given too much freedom gave.

Escape, Trial and Execution (1945–1947)

After the occupation of Slovakia by Soviet troops in April 1945, Tiso fled via Austria to Altötting in Bavaria . Here he hid with the knowledge of the Munich Cardinal Michael Faulhaber for six weeks in the Capuchin monastery of St. Anna . The cardinal also stood up for Tiso in the Allied military government:

"Since Dr. Jozef Tiso kept religious life alive in his country despite some difficulties, I ask not to equate him with other political leaders of former opponents of the Allied powers. "

Tiso was still by the Allies delivered to the Czechoslovak government on April 15, 1947 in a trial before the Czechoslovak People's Court to death by the strand convicted. In Slovakia it was widely expected that Tiso would be pardoned by Czechoslovak President Edvard Beneš. However, he refused the pardon and Tiso was executed as a war criminal on April 18, 1947 .

The execution of Tisos led to unrest and anti-Czech rioting in Slovakia and fueled renewed aspirations for independence from the Czechs. In his last message to the Slovak people, Tiso stated:

“The cohesion of the nation be baptized through my sacrifice. I feel like a martyr of the Slovak people and the anti-Bolshevik point of view. "

The trial is rated primarily by the Slovak public, but also by international historians, as a political show trial staged by the communists and the Czechoslovak President Edvard Beneš. Even before the end of the war, Beneš said several times about Tiso: “Tiso should hang”, and “two presidents cannot rule”.

The communists in particular were determined to enforce the execution of Tiso, as they wanted to use the trial against Tiso as a starting point for an attack on the newly formed Democratic Party in Slovakia , which stood in the way of the communist strivings for power. The communists insisted on the execution of Tisos also because they saw it not only as a symbol of the defeat of the supporters of the Slovak People's Party, but also as an impetus for the split in the Democratic Party. They assumed that the representatives of political Catholicism and the Church would blame Tiso's execution on an inability of the Democratic Party, and that the Catholic part of the party would split off.

Furthermore, five of the seven judges who sentenced Tiso to death, as well as the court chairman Igor Daxner, were members of the Communist Party. The defense of Tiso was made difficult or completely denied access to a lot of important information. For example, the court chairman Igor Daxner rejected Tiso's defense request that the Jewish head of Tiso's presidential chancellery, Anton Neumann, who was responsible for distributing the president's certificates of exception to Jews, be questioned about the number of certificates actually issued.

Tiso is still venerated as a martyr by large parts of the Slovak population , with the Slovak National Party and parts of the Catholic clergy also striving for his beatification and canonization .

ideology

His ideology was based on Catholic moral theology and was heavily influenced by Othmar Spann's corporate state theory. At the same time he adopted ideas from the scholastic philosophy of the Middle Ages, neo-scholasticism and the naturalism of the Enlightenment period. From time to time Tiso confessed to liberalist ideas, the ideals of the French Revolution and the individual freedom of the individual in society, but these confessions took a back seat to his nationalist ideas. In practice he followed the ideas of romantic nationalism. In order to strengthen the self-confidence of his Slovak compatriots and to find a justification for a Slovak nationalism , he developed an ideology of history that assigned the Slovaks the linguistic and geographical middle position in Slavicism . However, Tiso emphasized in December 1938:

“We are not and will not be advocates of imperialist nationalism. Our nationalism is a moral force that binds us to the Slovak tribe and its traditions that our fathers built. Our nationalism is not a biological drive, but a moral one, does not mean hating anyone, but a passionate love for our individuality. […] As Christians we will follow the resolution that teaches us: 'Love your neighbor as yourself!' "

The brief period of state independence under Svatopluk I and Mojmír II in the Great Moravian Empire of the 9th century was valued by Tiso as the high point in Slovak history . He raved about a medieval hierarchical order under the influence of a strong, strictly authoritarian Roman Catholic Church. He saw the Slovaks themselves as a people determined in the plan of creation as the bearer and champion of a renewal of pure Slavery in the political, moral, religious and cultural areas. Before the Slovak people could take on this task, they would first have to be recognized as a nation and subordinate their inner orientation to the Catholic-Christian tradition. On February 2, 1939, Jozef Tiso declared to Svoradov students in Bratislava:

"Slovak nationalism must not turn against Catholicism, because turning away from Catholicism is tantamount to separating the tree from its root, meaning death, because this would be a turning away from the nation from its history."

Tiso advocated Slovak autonomy within Czechoslovakia, but only wanted to achieve this in accordance with the laws of the constitution. In terms of foreign policy, especially after Slovak independence, Tiso advocated a Catholic-West Slavic bloc in which the Poles, Slovaks, Croats and possibly also the non-Slavic Hungarians should unite to defend Catholic and Slavic national interests. Tiso believed that only through such a bloc could he prevent the advance of "Soviet-Czech communism" , fascism and National Socialism, in whose ideologies he saw the existence of these peoples at risk.

In the First Slovak Republic, Tiso was considered the undisputed figure of integration of the Slovak patriots , i.e. the conservative-moderate wing of the Slovak People's Party, which rivaled the Slovak National Socialists . He not only represented the Catholic clergy, whose members held important positions in the state, but also the younger secular milieu, to which men such as the Minister of Economics Gejza Medrický or the chancellery head Karol Murín can be attributed. Concerning the state organization, he advocated an authoritarian and corporate state regime based on the model of Austro-fascist Austria and Salazarist Portugal . In 1943 Tiso commented on his party's role in Slovak society as follows:

“The party is the nation and the nation is the party. The nation speaks through the party. The party thinks for the nation. [...] What harms the nation, the party forbids and denounces. [...] The party will never be wrong if it always has only the interests of the nation in mind. "

Through his pragmatic writings and his defense speech before the National Court in March 1947, Tiso provided insights into his ideological objectives, which were sensitively interpreted by Štefan Polakovič and Milan Stanislav Ďurica .

Reception in contemporary history

Controversy in Slovakia today

Slovak society is very polarized in relation to Jozef Tiso. While one side, above all opponents of the authoritarian People's Party regime, accuse him of deporting the Jews and suppressing the Slovak national uprising, Tiso is revered in Catholic-conservative and nationalist circles as a hero who saved Slovakia from it like the Czech Republic from the Third To become empire or to be divided between Hungary and Poland. The supporters of Tiso emphasize above all the economic and cultural upswing that the country experienced during his presidency.

After Slovakia's independence in 1993 under Prime Minister Vladimír Mečiar , not a single politician distanced himself from Tiso. Mečiar avoided speaking negatively about the Tiso regime on the anniversary of the Slovak National Uprising. In 1993, on the 55th anniversary of Andrej Hlinka's death , the Slovak diocesan bishop Alojz Tkáč called on the “Czech brothers” to collectively apologize for the execution of Tiso.

The then Czech President Václav Havel rejected the request on the grounds that "Jozef Tiso was convicted by a Czechoslovak court and not by the Czech nation or the Czech President" . In Slovakia, on the other hand, the bishop's attempt at rehabilitation received great applause, as Tiso was and is revered by large sections of the population as a martyr and symbol of Slovakia's striving for independence. In 1997 a statue in honor of Tiso was erected in the municipality of Čakajovce ( Okres Nitra ). This was damaged several times, but was left in place.

On March 14, 2000, the chairman of the Slovak National Party, Ján Slota , as mayor of Žilina, had a memorial plaque put up for Tiso in the Slovak city. In 2008 the Archbishop of Trnava Ján Sokol celebrated a commemorative mass for Tiso and praised the period of the First Slovak Republic as a time of relative prosperity for Slovakia.

However, Sokol spoke out against the beatification of Tiso in an interview. He justified his view with the fact that a politician must also compromise, but a beatified must also be ready to die for his convictions . Former Public Prosecutor General of the Czech and Slovak Federal Republic , Tibor Böhm, made a public statement that Tiso was not a war criminal.

The long-time KDH party chairman Ján Čarnogurský again stated that Tiso was not the main political person responsible for the deportations of Jews:

“The government started the deportations even before the Jewish Code was passed into law! He (Tiso) was the President, so from this perspective he had the main responsibility. [...] The main responsibility for the deportations lay with the government, whose chairman was Vojtech Tuka. And who is talking about Tuka today? "

The vice-chairman of the Slovak Social Democrats of the SMER-SD Dušan Čaplovič declared himself convinced that Tiso must be viewed in the context of the time:

"Since Tiso was in a political position, he had a responsibility, but I would not see it as uncompromisingly and clearly as it is often presented in the media."

And the vice-chairman of the Slovak National Party Jaroslav Paška said:

"He was faced with the choice of having Slovakia dismembered for the benefit of neighboring countries, or of taking on the burden of maintaining the state in this environment and protecting the people from the consequences of the Second World War."

The former Slovak Prime Minister and party leader of the SMER-SD Robert Fico stated in January 2007 that he had a negative view of the First Slovak Republic and that this period was perceived as the “fascist state of Tisos” .

Among Slovak historians who have a very positive attitude towards Tiso and who in some cases openly demand its rehabilitation , for example Milan Stanislav Ďurica , Konštantín Čulen and František Vnuk should be mentioned. Ivan Kamenec , Dušan Kováč and Pavol Mešťan are among the representatives of a strongly negative assessment of Tiso . Róbert Letz , Ivan Petranský and Martin Lacko are among those who view Tiso in a balanced way, both positively and negatively .

International point of view

Outside Slovakia, most historians ascribe some of the responsibility or even the main blame for the persecution of the Jews in Slovakia.