Kalmenhof

The Kalmenhof is a socio-educational institution of youth and handicapped aid with training and teaching in the regional middle center Idstein in Hesse , a former Nassau residential town . The facilities of the Kalmenhof (formerly also Calmenhof , Idiotenanstalt Idstein or Calmischer Hof ) are partially listed . It is operated by a subsidiary of Vitos GmbH .

The eventful history of the healing and care facility founded in 1888 goes back to the Middle Ages . During the time of National Socialism , it was an intermediate institution for the Nazi killing center Hadamar with hundreds of euthanasia murders in the children's department . The involvement of individual Kalmenhof employees in the crimes of National Socialist racial hygiene was investigated in the so-called Kalmenhof Trial in 1947. After the institution was taken over by the State Welfare Association of Hesse, there were serious cases of abuse of the children in the home in the 1950s and 1960s. After reforms and restructuring in the 1970s, it was not until the early 1980s that the examination of the Kalmenhof's National Socialist past began.

Location and description

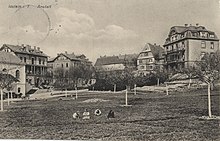

The Kalmenhof connects to the south of Idstein's old town. It is located at the foot of the Idsteiner Taubenberg on the three-hectare site between the streets Veitenmühlweg , Schulze-Delitzsch-Straße and Seelbacher Straße / Frölenberg . The street Veitenmühlberg leads through the area. The facility at the foot of a slope with extensive green spaces such as the director's meadow consists of several buildings.

Group houses are the Rudolph-Ehlers-Haus , the Rosenhaus , the Loni-Franz-Haus and the Buchenhaus with the central kitchen. In addition, there is the Star House and the Star Hall , warehouses, an employee residence, the outdoor swimming pool, workshops, the former hospital, the laundry and the main building on the driveway. The buildings differ significantly in their architectural style due to the different times they were built.

The nursery at Grunerstraße 41 , the Landhaus am Hofgut Gassenbach and the Charles Hallgarten youth home (In der Ritzbach) are located outside the main site. The nursery has 3,500 square meters of greenhouse space and 8 hectares of land.

organization

The State Welfare Association of Hesse (LWV) as the owner of Vitos GmbH is the sponsor of Vitos Teilhabe gGmbH and the Max-Kirmsse-Schule that emerged from Kalmenhof.

The Kalmenhof has differentiated facilities for disabled and youth welfare with a workshop for disabled people and with dormitory areas for mentally disabled adults and for disabled children and young people. As part of youth welfare, there are different housing options for children and young people, as well as semi-stationary and outpatient educational assistance. The former social education center Kalmenhof operates today as Vitos Teilhabe gGmbH . At Vitos Kalmenhof , the largest employer in the city of Idstein, around 350 employees were working in the areas of youth welfare and assistance for the disabled at the beginning of 2011.

The Vito's youth services Idstein (Book House) serves about 200 children and young people, supplemented by outreach family support with trained social workers and the selection and support for foster families for children who need a reliable place to live long term. The Vito's disability assistance for children and adolescents has 45 stationary places to children from school age who live on Kalmenhof at the Rose House and Loni-Franz-house.

The Vito's disability assistance for adults Idstein (Rudolph Ehlers-house) has up to 74 seats with living and working conditions for mentally and physically disabled people.

Mentally handicapped, behavioral and multiple handicapped men and women are looked after in the country house. There are also smaller groups in the surrounding towns. In 2010, 38 people with intellectual disabilities worked in the nursery on Grunerstraße.

history

The origins of the Kalmenhof

The origin of the Kalmenhof was the Stockheimer Hof . The associated estate was founded in 1350. The Lords of Stockheim , Burgmanns of the Counts of Nassau , built the main house of the court that still exists in 1599. In 1661 a large part of the Stockheim estate was sold and connected to the Gassenbach estate . During the Thirty Years' War , the Stockheimer Hof served as a refuge for displaced persons, among other things. The Stockheim line died out in 1702. A number of owners followed, among them privy councilor Johann Henrich von Kalm († 1776), who acquired the estate in 1768. The name Kalmenhof, which is common today, can be traced back to him.

The Kalmenhof was already connected to an educational facility from 1849 to 1877 when Georg Philipp Weldert's (1795–1863) toddler school was located there. She later moved to a building on the Zuckerberg .

Foundation of the "Idiotenanstalt Idstein"

The second half of the 19th century was characterized by social upheaval. As a result of rural exodus between 1871 and 1910, the population of Frankfurt grew by 355 percent, Wiesbaden by 207 percent and Offenbach by 148 percent. For the working-class families, mostly living on the subsistence level, the accommodation of disabled family members in an institution meant a considerable relief, especially since the governor took over the costs of accommodation as a result of the amendment of the support residence law from 1892.

A final impetus for founding another idiot institution in the greater Frankfurt area was the fifth conference for idiot nursing from September 16 to 18, 1886 in Frankfurt. Although the Kalmenhof was not on the agenda, it can be assumed that its establishment was discussed intensively on the sidelines of the conference.

The motives for founding the facility in Idstein are not known. Basically, it was common to move such institutions to the countryside, since there the labor of the pupils could be used more sensibly and the citizens of the cities did not notice the "custody" of the disabled.

The main initiators were the Protestant pastor Rudolph Ehlers , the Jewish banker and philanthropist Charles Hallgarten and the Frankfurt city councilor Karl Flesch . What they had in common was social engagement. Ehlers himself had a mentally handicapped daughter.

In addition to these main initiators, the industrialist Hermann Sonnenberg, the company owner Carl Bolongaro , the architect Steinbrinck, August Lotz, a former assistant to Heinrich Hoffmann , regional director Otto Sartorius (the only non-Frankfurt citizen) and the Frankfurt police chief August von Hergenhahn were involved in the establishment. The latter is also mentioned on the relief of the founders with Ehlers and Hallgarten, although his role in the founding was significantly smaller.

The foundation of the association for the Idiotenanstalt Idstein took place on April 30, 1888. The primary concern was "to establish and maintain an institution in which idiots (feeble-minded, nonsensical and epileptic) of both sexes, of all ages and religious denominations, and as far as possible for Bringing up earning capacity or appropriately employed ” . The founders of the association made high demands on educators and directors of the institution: "They should show, in particular by treating the pupils, that they have absorbed the spirit of human, religious and moral education."

On May 1st, the Hallgarten couple signed the purchase contract for the Kalmenhof estate. The official opening with 12 to 18 children followed on October 7, 1888, with the teacher Johann Jacob Schwenk, appointed as director . The manor house, which formed the core of the institution, was in a dilapidated state and had to be converted for the new use. The non-profit association was not founded by government or church bodies. The Kalmenhof was designed as a non-denominational, reformed institution. Up to the 1930s, up to 20 percent of the residents were Jewish and received appropriate training and hospitality.

The expansion

It became clear early on that the Kalmenhof, which was initially occupied almost exclusively with children, was insufficient. The first extension building, also called the Birkenhaus , planned and executed by Steinbrinck, was inaugurated in June 1891. At the end of 1892 this house was almost fully occupied. In September 1894, the construction of the boys' house, the Tannenhaus , begun in 1893 , was inaugurated. From then on, the Stockheimer Hof essentially served as the director's residence.

Initially, the pupils were only introduced to various handicrafts in preparation for their jobs. In 1894 a trained brush maker was hired for job-specific training and in 1889 a special school was set up. Ten years after it was founded, the Kalmenhof housed 114 pupils. Three years later, the boarding house for pupils from better-off families was inaugurated, and in June 1905 the old people's home In der Ritzbach near Idsteiner train station. The nursing home was located around 800 meters from the main site and was intended to accommodate adult pupils who were not capable of education. In 1907 the gym was built.

The year 1908 was difficult for the institution, as both Ehlers and Hallgarten died in quick succession. Hallgarten's son Fritz Hallgarten took over the position of treasurer from his father. Ehlers' successor in the chairmanship of the board was Privy Councilor Varrentrap.

In 1910 Max Kirmsse came to the Kalmenhof as a special school teacher and worked there until 1922. The Max Kirmsse School in Idstein was named after him. In 1911, the first medical column of the Red Cross was launched in Idstein, which mainly consisted of Kalmenhof employees.

The end of the expansion was initially reached in 1913, when the Frauenaltenheim and the central company building were inaugurated. At that time the Kalmenhof already had seven workshops in which nine master craftsmen trained 41 pupils.

In these years, the association relied financially on income from state care allowances and its own products as well as on donations and grants.

The First World War

The Kalmenhof lost ten employees due to conscription for military service during the First World War . The personnel shortage was exacerbated by the arrest of two South African- born employees who were considered enemies of the state because of their British citizenship . However, the authorities were persuaded to naturalize her because she moved to Germany early on. As Germans, however, they were then called up for military service and were no longer available to the institution. Due to the staff losses, restructuring was necessary in order to maintain school and teaching operations. More women were employed; Apprentices were employed as auxiliary carers.

The supply situation was problematic in the war years. While the Kalmenhof's income stagnated, expenditure on food supplies doubled. Accordingly, pupils suffered from malnutrition.

At the end of 1917 it was reported that 52 residents had been drafted during the war years. Ten of them were awarded the Iron Cross , five fell and many others were wounded.

| Occupancy of the Kalmenhof | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| year | Pupils | |||

| 1888 | 12-18 | |||

| 1898 | 114 | |||

| 1912 | 255 | |||

| 1917 | 315 | |||

| 1923 | 250-300 | |||

| 1933 | 630 | |||

| 1937 | almost 1000 | |||

| 1954 | 1100 | |||

| 1962 | 700 | |||

| 1966 | about 500 | |||

| 1969 | 539 | |||

| 1971 | 330 | |||

| 1972 | 220 | |||

| 1978 | almost 200 | |||

| 1988 | almost 200 | |||

| Source: 100 years of Kalmenhof 1888–1988. | ||||

Inflation and reconstruction

Due to the general economic situation and inflation , the financial situation of the educational institution was extremely difficult. In addition, the boys' house was badly damaged by fire in February 1922. The club was on the verge of ruin, as the financially strong supporters had also lost their financial support. Since the association could no longer cope with the requirements on a private level, the board of directors decided in 1921 to join the Association of Hospitals in Frankfurt and Angegenden . The boys' house was rebuilt with the help of the Idstein population. Director Schwenk died in 1922. Emil Spornhauer followed him.

With the number of 250 to 300 pupils falling, the bottom of the valley was passed in 1923. With the stabilization of the currency, the economic situation of the Kalmenhof, renamed Heilerziehungsanstalt Calmenhof zu Idstein im Taunus , also recovered. During this time, the Kalmenhof had a lasting impact on life in Idstein. The commander of the English 1st Battalion of the Royal Ulster Rifles, stationed ten months in Idstein in 1926, noted : "The chief local industry was, apparently, breeding lunatics and keeping asylums for them" (The main local trade was apparently to educate lunatics and provide them with accommodation To provide).

In 1927, under the medical direction of Fritz Klein, operations began in a newly built hospital with 26 places. In the first few years it served as a medical observation station and as accommodation for those with short-term illnesses. In 1926, a complex of buildings from the neighboring bankrupt leather factory was bought and converted into a home for apprentices. Since then it has been the main building of the institution. This measure increased the capacity of the Kalmenhof by another 200 spaces by 1929. The architect Ludwig Minner planned and supervised the necessary renovation as well as that of the neighboring laundry building in 1930.

After several attempts, it was possible in 1930 to take over the nearby Hofgut Gassenbach from the city of Frankfurt. It strengthened the economic basis of the Kalmenhof, as it enabled extensive agricultural use on 700 hectares of arable land.

The Kalmenhof under National Socialism

Takeover and use as a hospital

As early as April 4, 1933, shortly after the National Socialist “ seizure of power ”, Director Spornhauer was forcibly removed from office by an SS troop, according to eyewitness reports . The NSDAP Hessen-Nassau-Süd temporarily installed Ernst Müller. The board of directors tried to oppose the takeover by the National Socialists and resigned from office on August 1, 1933. Provincial councilor Fritz Bernotat, as the head of the institutional sector at the provincial governor, took over the chairmanship of the administrative board and board. This meant a synchronization and the loss of the free sponsorship of the Kalmenhof.

This change in leadership was also associated with a completely different approach to the home residents. While pedagogical goals were in the foreground before, only masses of people were to be accommodated "economically efficiently" at minimal cost. A higher occupancy should be ensured with reduced operating costs. By 1937, the number of apprentices in the home fell from 270 in 1933 to 37, while in the same period the occupancy rose from 630 to almost 1,000 people.

At the same time, the principle of interdenominationalism was given up. While in 1932 around 150 pupils of the Jewish faith were still being looked after by a Jewish teacher, a Jewish assistant and a Jewish cook, this commitment was discontinued in 1936. At the same time, the number of residents of the Jewish faith was reduced to around 60.

With the start of World War II, one in 1939 in Kalmenhof hospital of the armed forces equipped with 500 seats. The Kalmenhof was obliged to provide the hospital with accommodation, laundry and food. In order to create space for the hospital, many of the Kalmenhof's pupils were moved to other institutions, reducing the occupancy to 350. In 1940 the hospital was closed again and an approximately 600-strong Wehrmacht intelligence unit was stationed in Kalmenhof, which also had to be maintained by the Kalmenhof. In 1941 another hospital was set up, initially with 300 beds and at the end of the war 1300 beds. During this time, the Wehrmacht used all buildings except for the external retirement home. All around 350 pupils were busy with the management of the facility. There was almost no educational work. Due to the unmanageable circumstances, Müller, who was still formally appointed as acting head of the Kalmenhof, resigned from his position in 1941 and reported "for use in the East". Wilhelm Großmann, who had been office manager and accountant until then, took over his position.

Forced sterilizations, intermediate institutions, killings

After the destruction of files at the end of the Second World War, it is difficult to deal with the murders of the sick at the Kalmenhof during the Nazi era . It is not known exactly how many victims the National Socialist "euthanasia" ( Action T-4 ) claimed at Kalmenhof. It is assumed that the number of fatalities is between 600 and 1000. It is known that the first killings occurred at Kalmenhof from the end of 1939.

From 1934 onwards, forced sterilizations were carried out at the Kalmenhof . At least 216 residents were harmed. The basis for this forced sterilization was the law for the prevention of genetically ill offspring (GzVeN) .

From August 1, 1938 to December 1939, Hans Bodo Gorgaß was the chief doctor at the Kalmenhof. He himself was referred to as a "butcher" by doctors involved in the extermination program and was later responsible for the deaths of thousands of people in other institutions. On June 28, 1939 Mathilde Weber came to Kalmenhof as an assistant doctor. After Gorgass's departure, she took over the medical management, which she held until May 10, 1944. She left because of tuberculosis . She was followed by Hermann Wesse as a doctor until the end of the war, where he was again represented by Weber in December 1944 and January 1945 due to vacation. Wesse had previously worked at the Bedburg-Hau and Andernach institutions and headed the children's departments in Waldniel and Uchtspringe .

The Kalmenhof as an intermediate facility

At the end of 1939, various sanatoriums and nursing homes were converted into killing centers as part of the T-4 campaign . There, "useless eaters" were massacred, including gassing . The Kalmenhof was an intermediate facility of the Hadamar killing facility, as were the facilities in Andernach , Eichberg , Schrebs and Weilmünster . Killings were carried out in Hadamar from January 1941. The function of the intermediate facilities was the "interim storage" of the transports destined for Hadamar. This means that it should be ensured that only as many victims were brought in as could be murdered immediately afterwards. The transfers were carried out daily with so-called Gekrat buses, except on weekends. At Kalmenhof, the victims were housed makeshiftly on straw beds in the gym or later in the basement of the old people's home. Among them were political prisoners , communists and anarchists who had been unceremoniously declared insane and unworthy of life .

From 1940 on, registration forms for selection were distributed at Kalmenhof, with which the pupils were recorded and which were sent back to the Reich Committee for the scientific recording of serious diseases caused by heredity and genetic makeup . It was there that life and death were decided. On the basis of these registration forms, a total of 232 regular pupils were transported to Hadamar in five transports and murdered there shortly after arrival by gassing. The oldest of them had lived in the Kalmenhof for forty years. How many people the Kalmenhof was just a stopover on the way to Hadamar can no longer be determined. Only individual transports can be traced from the documents of other institutions, such as on July 9, 1941 with 136 people from Gütersloh or several transports from the Haina monastery . According to Großmann, “it was a coming and going of relocations, interim transports” .

On August 24, 1941, Hitler gave verbal instructions to end Operation T-4 and to cease “adult euthanasia” in the six killing centers. This instruction was based on public protests against the action. The " child euthanasia " was continued, however, as was the decentralized killing of disabled adults in individual sanatoriums and nursing homes. So the killing finally shifted to the Kalmenhof. The high bureaucratic effort caused by the Nazi regime was striking. This operated a certain concealment and gave the killing a semblance of legality.

The killings of "life unworthy of life" in the Kalmenhof

When the transports to Hadamar were discontinued, a so-called children's department was set up on the second and third floors of the hospital in Idsteiner Kalmenhof . Most people killed by being poisoned with drugs or starving to death. Victims were children and young people with intellectual disabilities, epileptics , Mongoloid , idiots and imbeciles , but also young people who from the perspective of the Nazis as work-shy or antisocial were. It was noticeable that those killed mostly only stayed a few days in the Kalmenhof before they died. The so-called regular pupils were significantly less likely to be killed because they were used to run the Kalmenhof, the hospital and the management of the Gassenbach estate. Formally, the aforementioned Reich Committee in Berlin decided to kill by authorizing them. In doing so, it relied on the assessments of the doctors on site, in particular with regard to usefulness and educational ability. The doctors were able to postpone children who had been authorized to kill. So the final decision about a killing always rests with the Kalmenhof doctors. Contrary to their own later representations, they were therefore not “mere recipients of orders”. The staff deployed at the Kalmenhof received a special payment for each “death”, initially at 5.00 RM , later at 2.50 RM.

Since the municipal cemetery was insufficient for the numerous deaths at Kalmenhof, the victims were temporarily buried in the Jewish cemetery , which was purchased in 1942. When this was not enough either, a cemetery was set up on an arable land facing away from the city center near the hospital. The funerals were carried out as quietly and secretly as possible and were ultimately a simple burying. The folding coffin used here could be used many times.

The evangelical pastor Boecker, who lived in Idstein from 1932 to 1947, noted in the church book “... death now rules in the Kalmenhof”.

It is significant that there were no fatalities either during an absence of several weeks due to illness or during a six-week training trip. During this advanced training course in Heidelberg she visited the psychiatrist Professor Carl Schneider , a key figure in the medical crimes of the Nazi era.

It is also known that at Weber's request because of her illness at the end of her service life, no more transports to the Kalmenhof were arranged. When Wesse took over the position again, he expressly asked to be sent "Reich Committee children" whom he wanted to murder. Bernotat pointed out that he should " be satisfied with what is there" . These were no longer children with mental or physical disabilities, but rather uncomfortable, rebellious and behavioral children whose killing was then arranged by Wesse.

Fritz Geisthardt wrote that the Kalmenhof was killed without “bureaucratic effort” and in “wild euthanasia”. In fact, this only applied to a minority of cases, mostly at the beginning and towards the end of the war. Affected were children who had attempted to escape several times, the victims of human experiments with electric shocks, hormone preparations, etc. by Mr. Wesse, but also confidants, i.e. pupils who were involved in the operation of the children's department as assistants. Ludwig Heinrich Lohne, who was employed as a grave digger at Kalmenhof, only experienced the end of the war by defeating Wesse, fleeing and hiding in Idstein for several days until the Americans invaded.

resistance

There was also resistance to the crimes. The educator Loni Franz (1905–1987), who worked in the nursing home , stood out in particular. She tried to keep the children away from the hospital. In many cases this did not succeed, but by either sending the children back to their parents or hiding them with acquaintances and friends in Idstein, she was able to save the lives of some. She also tried to move the children from the Kalmenhof to institutions without a children's department such as the Philippshospital in Riedstadt or the medical education and nursing homes in Schubb and thus to protect them or at least to alleviate the suffering caused by the lack of food, clothing and warmth.

In her honor, a new building was named Loni-Franz-Haus in 2009 . A street in Idstein also bears her name.

The Kalmenhof Trial

After the war, the process of coming to terms with what happened during National Socialism began. First, in 1945, the deputy director Wilhelm Großmann, the prison doctor Hermann Wesse, the nurses Änne Wrona and Maria Müller were arrested and questioned by the American occupying forces on suspicion of willful murder. The Kalmenhof case was handed over to German jurisdiction in March 1946. In September 1946, the Idstein District Court issued an arrest warrant for the named persons and the former prison doctor Mathilde Weber.

After the negotiations at the Frankfurt Regional Court and the appeals at the Frankfurt Higher Regional Court , the following judgments were made:

- Wilhelm Großmann: Four years and six months imprisonment. However, he did not have to commence the sentence because of the pardon by the Hessian Minister of Justice. The Idstein magistrate supported the request for clemency.

- Hermann Wesse : The initially pronounced death sentence was commuted to life imprisonment by the Düsseldorf Regional Court in 1949 after the appeal at the Frankfurt Higher Regional Court had been rejected . The background to this was the abolition of the death penalty in Germany and thus the prevention of its execution. The conviction of Wesse was largely made possible by the exact reconstruction of the circumstances of death of the "mentally and physically perfectly healthy" Ruth Pappenheimer (who had a Jewish father), the 15-year-old Karl-Heinz Zey from Langendernbach , the 14-year-old Georg , supported by witness statements Rettig and the 23-year-old Margarethe Schmidt. In 1968 the sentence was finally waived. Wesse is the only doctor involved in the crimes to serve a long prison sentence.

- Mathilde Weber: Three years and six months in prison. First, a death sentence was passed. Due to a signature campaign and the support of requests for clemency from the Idstein magistrate, the sentence was reduced. After she had served two thirds of the sentence, the remainder of the sentence was waived as part of a pardon. Until 1994 she lived in the immediate vicinity of the Kalmenhof in Idstein.

- Nurse Änne Wrona (head nurse 1944–1945): acquittal

- Nurse Maria Müller: She escaped punishment by escaping and was never found. When questioned by officers of the American military administration, she had confessed to murders.

- Fritz Bernotat (Chairman of the Kalmenhof Association): He died in 1951. Until then, he lived under a false name near Fulda and remained anonymous.

- Head teacher Link, educator at the Kalmenhof, poisoned his wife after the invasion of the Americans and committed suicide.

Hospital and refugee camp

When the US Army marched into Idstein on March 28, 1945, the occupying power ran the Kalmenhof. The hospital continued to serve wounded soldiers and was closed in the course of 1946. The Kalmenhof housed evacuees from cities damaged by the air war such as Darmstadt and Frankfurt , and from December 1945 displaced persons and refugees from the eastern regions were quartered. The spatial situation was very limited during this time. The supply of food and fuel was difficult. In the hungry winter of 1946/47 in particular , the residents burned furniture and interior fittings to avoid freezing to death. Emil Spornhauer took over the management of the Kalmenhof again from 1945, which Max Kirmsse temporarily held temporarily. With an occupancy of approx. 800 people, approx. 1100 admissions and dismissals are documented for 1946.

Post war until 1970

In 1945 the Jewish cemetery was returned to the Jewish asset management. In 1948 the association for the educational institution was dissolved and the Wiesbaden district association took over the institution. In 1949 Ernst Ilge succeeded Spornhauer as director. By 1953 the occupancy of the Kalmenhof increased to over 1000 pupils. Among them was Harry von de Gass (1942–2005), who lived in the Kalmenhof from 1951 and developed into the Idsteiner original until his death .

In 1953, the State Welfare Association (LWV) Hessen was founded and sponsored the Kalmenhof. In 1954, the home special school received a new building as the beginning of the separation of the school from the Kalmenhof group. This ended in 1971 with the establishment of the Max Kirmsse School . The Kalmenhof reached its maximum occupancy level in 1954 with 1,100 people. From 1957 to 1971, various extensions and new buildings were built to accommodate the growing number of people and the differentiation of the learning groups according to the type of disability. In 1966 the country house at Hofgut Gassenbach was built.

Abuse

In the 1950s and 1960s there were serious cases of abuse under the director Ernst Ilge, who cultivated a dictatorial leadership style, and Alfred Göschl, who has been active since March 1963. In addition to taking advantage and sexual abuse , draconian punishments were also known, which included, among other things, pocket money or food deprivation, beatings, cane blows, shackles, imprisonment and worse. These attacks are partly related to educational methods, which also include violence and intimidation.

“ Volker was already asleep when the light was switched on in the bedroom in the middle of the night. An educator, of whom many children were very afraid, came in and stood in front of the first bed that came up. "Get up!" The boy, his name was Heinz, had not got up yet when he was hit in the face. Isn't that faster? Heinz had raised both hands like a shield over his head and was silent. "Anyone else a good night kiss?" "

These events only came to an end on November 15, 1969, when a report by the journalist Ulrike Holler on the conditions at the Kalmenhof was broadcast on the youth radio of the Hessischer Rundfunk . An article in Der Spiegel followed on November 17th . The reporting coincided with the so-called home campaign , an initiative of the APO , which generally dealt with the conditions in German children's and youth homes that were perceived as intolerable. Notices followed and the Hessian state parliament also dealt with the allegations. On July 7th of the following year, Göschl was finally recalled and transferred to the headquarters of the LWV in Kassel . Investigations by the Wiesbaden public prosecutor's office against him were initiated after a complaint for corruption and exploitation of addicts by the therapeutic educational action group - action group welfare homes , a group of the APO, but stopped without charge. Until his early retirement he worked as an administrative director at LWV in Kassel. The estate manager Hofbauer was also reported for taking advantage of subordinates and the LWV's educational assistance department for tolerating, favoring and violating the duty of supervision. Again, no charges were made.

The psychologist Gertrud Zovkic, who has been working at the Kalmenhof since early 1966, played a key role in clearing up these processes. Right from the start, she also advocated professional training for educators. She strove to dissolve the in-house training, which was only recognized within the LWH, and favored the state-recognized training at a college for home education. The psychologist went so far that she suggested individual personalities to leave the Kalmenhof, i. H. to break off the in-house training and to complete a state-recognized training. However, this view has not been approved by those in charge of the administration. Finally, the “nest dirtier” was forcibly transferred from the LWH to the LWH home Steinmühle near Ober-Erlenbach , which was dissolved in 1974. Ms. Zovkic protested against this under labor law. After further arguments, she was fired. The settlement suggestion, "like her adversary Alfred Göschl to be promoted to the head office in Kassel, was indignantly rejected by the LWV".

Five educators had to answer for the proceedings before a Wiesbaden lay judge. They received fines of up to DM 100 .

When the coordinator Karl Reitinger took office in 1972, he found that out of ninety active educators, only four had a pedagogical training. It is also known that under Ilge many of the educators employed had a soldier or Nazi past and were personally connected to him. Ilges personnel policy was even criticized by representatives of the LWV during his tenure.

Reforms and restructuring

In 1970, the LWV initiated reforms in the Kalmenhof after the abuse scandal was uncovered. The psychiatrist Berthold Schirg became the acting head. The LWV worked out a concept in cooperation with senior employees of the Kalmenhof, which envisaged the decentralization of the Kalmenhof facilities into several small, pedagogically independent homes. Accordingly, the new director no longer acted as director, but as coordinator, with the aim of gradually handing over his powers to the individual homes. The LWV decided to improve the educator key and reduce the group size. From then on, only state-recognized educational specialists were employed. The occupancy was reduced to 330 people.

The reform process was accompanied by structural changes. In 1971 the boys 'and girls' houses were demolished as these buildings no longer met the requirements. Two new buildings in der Ritzbach outside the main site , which were actually intended as residential buildings for staff, were used provisionally to accommodate children in the home. The buildings were used until 1992 when three new buildings could be occupied. These buildings were built on the site of the former old people's home that burned down after the war. The sports center with gym and outdoor pool, used jointly with the Max-Kirmsse-Schule, was put into operation at the beginning of 1972.

In 1972 Karl Reitinger took over the office of coordinator. One of his main tasks was to implement the reform. This project came to an end in 1978, the four children's homes in the Ritzbach , Buchenhaus , Rosenhaus , Landhaus am Hofgut Gassenbach were independent, connected to the central service companies administration, kitchen and laundry. The home association was named the Kalmenhof Social Pedagogical Center .

Coming to terms with the past

Until 1961 there was a commemoration in the form of an annual private procession of a prison nurse with a few children, which led to the increasingly overgrown prison cemetery behind the hospital, where the majority of the children killed were buried after their murder. According to georadar examinations from 2019, further graves are suspected to be on the entire site of the institution and on the adjacent private property.

A public discussion of the events of the Third Reich took place late. A school garden had been laid out on the burial ground. In 1978, on the occasion of the 90th anniversary of its existence, coordinator Reitinger gave the wrong information out of ignorance that the Kalmenhof had served as an intermediate facility, but that there had been no euthanasia murders at the Kalmenhof. In April 1981, young people from Idstein visited Jurek Skrzypek, a survivor of the Holocaust, as part of a study trip to Poland organized by the Heftrich Protestant Parish . This drew attention to the events in the Kalmenhof. Pastor Siebert then turned to the management of the Kalmenhof, representatives of the parishes and the mayor of Idstein. The state welfare association formed a commission to uncover and document the crimes.

The events at Kalmenhof became known to a wider public through a report in the Idsteiner Zeitung and a publication in the Frankfurter Rundschau. Afterwards, citizens of Idstein also got involved in this matter. Exhibitions, information events and memorial services followed. In 1983 Dorothea Sick published a first research paper on the subject. Reitinger had served Sick as an informant in this context. On the day of national mourning in 1984, a memorial cross was set up at the mass grave on Veitenmühlberg. The memorial on Veitenmühlberg was inaugurated on May 24, 1987, and in the same year a warning plaque was attached to the fallen cemetery in Idsteiner Friedhof.

Since 1997 the permanent exhibition Der Kalmenhof has been providing information about the crimes of the Nazi era in the main building of the Kalmenhof.

On June 9, 2006, the first public discussion of the abuse incidents of the 1950s and 1960s took place as part of a specialist conference. The documentary film Die Unwertigen by Renate Günther-Greene , which deals with this topic in addition to the events during National Socialism, was partially shot in the Kalmenhof and also shown in the Kalmenhof in June 2010.

The city council of Idstein decided to have a memorial designed for the victims of violence and displacement . The first meeting of the working group took place on April 3, 2008. Students from the Pestalozzi School in Idstein also made designs for this monument.

On March 4, 2013, the ZDF broadcast the feature film And all have been silent , which is based on the experiences of the residents in the 1960s, as TV film of the week. After the feature film, a ZDF documentary of the same name was shown, in which former home children described abuse and mistreatment at Kalmenhof.

The first in the new Frankfurt old town misplaced stumbling block reminiscent of Jacob Hess , one of the victims of euthanasia killing at Kalmenhof.

Realignments for the future

From 1996 onwards, the LWV became aware of the idea of selling parts of the Kalmenhof grounds and leaving them to an investor for development. The city of Idstein responded by drawing up a development plan for the Kalmenhof site in order to secure a say in the future design of the site. The focus of the discussion was a possible development of the director's meadow north of the main building, which the city of Idstein wanted to keep as a green area.

The LWV filed a lawsuit against this development plan at the Hessian Administrative Court , which is being negotiated in 2011.

On July 13, 2004, the successor to the old house (Stockheimer Hof), the Rudolph Ehlers House, was inaugurated; it was created under the direction of the local planning office Guckes. In 2006 the Stockheimer Hof was handed over to the Guckes planning office. With that, the Kalmenhof lost its original building.

On June 8, 2008, the Loni-Franz-Haus was inaugurated as a supplement to the rose house. It was also built under the direction of the Guckes planning office. There was a serious fire in the nursery on September 10, 2011. Part of the warehouse and the hall were probably on fire as a result of arson . There was property damage of around € 50,000.

In September 2011, the University of Kassel was commissioned with a research project aimed at clearing up the physical and psychological humiliation at the homes of the LWV in the 1950s and 1960s and is headed by Mechthild Bereswill (sociology) and Theresia Höynck (law).

At the beginning of May 2012, the facilities of the Vitos Pedagogical-Medical Center Wabern were removed from Vitos Kurhessen and assigned to Vitos Kalmenhof, with the exception of the training companies there . The youth welfare service located in Wabern in northern Hesse will remain as a branch of the Kalmenhof. According to the group managing director Reinhard Belling, this measure serves to sharpen the profile as a youth welfare organization.

In July 2016 it was announced that Vitos was considering selling the former hospital and the surrounding area. The hospital owned by Vitos Rheingau is not a listed building. The euthanasia memorial and the burial ground are not affected by the sales considerations. The intention to sell led to public outrage and a unanimously passed urgency motion by all parliamentary groups in Idstein's city parliament to keep the memorial permanently and publicly accessible. "On the land in which victims were buried, buried or simply buried, no development may take place now and in the future," the decision says.

Individual parts of the site

Some of the Kalmenhof buildings are particularly noteworthy because of their age, their architecture or their history.

Main and workshop building

The main and workshop building of the Kalmenhof at Veitenmühlenweg 10 / Grunerstraße 2, with an L-shaped floor plan, is a listed building. The two wings of the building meet at the corner of the main driveway to the Kalmenhof area. The main entrance, which leads into the stairwell, is located on this tower-like part of the building. The building is characterized by the outwardly pointed barrel roofs of the two wings, the ogive arcade of the north wing and the Ver cleavage of the second floor of the west wing provided with tail gable dormers. The spacious staircase is characterized by the steel stair and balcony railings and the high rooms typical of the construction period. The column layout of the exterior view continues inside in the form of pillars that are clad with bricks, as are the walls on the upper floor.

The workshop building, also provided with slate cladding, connects to the main building via a bridge crossing the Veitenmühlberg . It is a hall construction with ribbon windows, which is to be regarded as contemporary-modern after its creation.

Stockheimer Hof

The stately, listed building at Obergasse 31 has a structure comparable to that of the mansions in Eltville and Geisenheim built by the von Stockheim family in the mid-16th century . The entrance, stair tower and the gable-side porch are all positioned on these buildings . The Stockheimer Hof shares the three-storey main building with a half -hipped roof with the house in Geisenheim. Two half-timbered storeys sit on the brick-built ground floor . The exposed half-timbering blends in with the half-timbered image of Idstein's old town, which is a listed building as a whole, even if the Stockheimer Hof is not included in this ensemble. Decorations are only found on the second floor and in the gable field. The semicircular stair tower with a hooded roof with a half-timbered floor stands out clearly. It is conceivable that the stair tower and substructure were parts of a previous building that were integrated into the structure. The coats of arms of Stockheim and von Hattstein are placed above the lower window of the bay porch . This is due to the wedding of Johann Friedrich von Stockheim and Catharina von Hattstein, daughter of Henn Hattstein in Camberg and Elisabeth Weißin von Fauerbach in 1591. The year of construction 1599 is also recorded there. Since 2006 the Stockheimer Hof no longer belongs to the Kalmenhof institution. Today's users use the name Stockheimer Hof on signs again.

The Kalmenhof cemetery

First of all, the first 300 victims were buried in the city cemetery. Since this was not sufficient for the numerous deaths at the Kalmenhof, the city of Idstein closed it to the pupils of the Kalmenhof. Another 50 or so victims were buried between February and October 1942 in the Jewish cemetery , which had been purchased in 1942. When this was not enough either, a cemetery was registered with the authorities on an arable land facing away from the city center near the hospital. The funerals were carried out as quietly and secretly as possible and were ultimately a simple burying. The folding coffin used here could be used many times. Often two or more corpses were buried in one grave. The graves were only marked by numbered metal crosses, there were no names.

After the end of the war there was probably no public interest in securing and maintaining the cemetery. During an inspection by the public prosecutor in 1946 under the direction of [Fritz Bauer], three grave fields were put on record, arranged in three rows, with a total of about 270 metal crosses.

In 1952, during the term of office of Mayor Willy Schreier, the new construction of the "Schöne Aussicht" building area took place, the properties of which, west of the street, protrude into the unsecured cemetery to this day. The metal crosses were still visible at the time.

In 1964, the shell of the official residence (also called the “officials' house” or “director's house”) including the corresponding sewer connection and access road was built. In this context, sheet metal crosses were "removed" from the affected terrace.

As part of the expansion of the Max-Kirmsse-Schule, which is directly adjacent to the site, blasting and earthworks were carried out on the site. In this context, it seems likely that tombs were destroyed.

The memorial, created in 1987, is too small, it does not cover the entire area of the cemetery. According to the historian Christoph Schneider, the grave fields were intentionally forgotten in the 1950s.

Memorial on the Veitenmühlberg

The memorial on the Veitenmühlberg was erected on the spot where the victims of the Nazi era were buried in mass graves. Up to the present there has not been any exhumation of the victims or the only rudimentary delimitation of the presumed burial ground. The memorial can be reached via the Veitenmühlberg street. When going to the cemetery of the killing center, one also passes the former "hospital" where most of the murders were committed. The memorial, which is divided into two parts, is not far from the hospital. The cemetery is not recognizable as such and, in contrast to communal cemeteries, is not recognizable on Google Maps or in other digital mapping systems. The low brickwork erected in 1987 forms a three-quarter circle and bears the inscription on its cover: “In memory of the victims of the tyranny. More than 600 children and adults from the Kalmenhof were murdered between 1941 and 1945. Many of the victims are buried here. The number and location of the individual graves are unknown. ” At the end of the adjoining grave field there has been a steel memorial cross with the inscription “ In memory of the victims of the crimes in Kalmenhof / Idstein during the Nazi era ” .

Hofgut Gassenbach

The Gassenbach estate is located about 500 meters south of the Kalmenhof. Today it belongs to the Mechtildshausen domain , where a group of the workshop for the disabled is active. The history of the estate can be traced back to the abandoned village of Gassenbach, which was first mentioned in 1316. From 1930 on, the Kalmenhof took over the estate. The complex, which was previously closed on four sides, is only partially recognizable. The former courtyard house takes up one narrow side. To the west there are a number of barns and stables with pointed barrel roofs. The facility is partially under monument protection.

literature

- Fritz Geisthardt: Idstein's story. In: Idstein. History and present. Magistrate of the city of Idstein, 1987.

- Landeswohlfahrtsverband Hessen (Hrsg.): The Kalmenhof then and now. Notes on the exhibition in the Kalmenhof. 1999.

- Christian Schrapper, Dieter Sengling (Hrsg.): The idea of formability. 100 years of socio-educational practice in the Kalmenhof educational institution. Juventa Verlag, Weinheim / Munich 1988, ISBN 3-7799-0780-1 .

- Dorothea Sick: "Euthanasia" in National Socialism using the example of the Kalmenhof in Idstein im Taunus. 2nd Edition. University of Applied Sciences Frankfurt am Main , 1983, ISBN 3-923098-08-1 .

- SPZ Kalmenhof (ed.): 100 years of Kalmenhof 1888–1988. From the "Association for the Idiot Institute in Idstein" to the "Social Pedagogical Center". 1988.

- Peter Wensierski: Beatings in the name of the Lord . The repressed history of children in care in the Federal Republic. Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, Munich 2006, ISBN 3-421-05892-X .

- Marita Schölzel-Klamp, Thomas Köhler-Saretzki: The blind eye of the state. The home campaign of 1969 and the demands of the home children of the time. Bad Heilbrun 2010, ISBN 978-3-7815-1710-3 .

- Christoph Schneider, Dr. Harald Jenner: Research Report Kalmenhof / Idstein Part 1 and Research Project Kalmenhof / Idstein Part 2 2018

Web links

- Homepage of Vitos Teilhabe gGmbH

- Vitos GmbH homepage

- Historical pictures of the Kalmenhof on alt-idstein.info

- Home child Heinz Schreyer

- The Max Kirmsse Collection at the University Library of Marburg

- Updated list of people murdered in Idstein and deported to Hadamar

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b Commitment to the Kalmenhof. ( Page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. In: Idsteiner Zeitung. July 15, 2010.

- ↑ vitos Kalmenhof: Introduction. Retrieved January 1, 2011.

- ↑ Peter Faust: Material on the "Stockheimer Hof" in Idstein Status: May 2009.

- ↑ Martina Schrapper: … 100 inquiries about the most urgent part… In: Christian Schrapper, Dieter Sengling (Ed.): The idea of imageability - 100 years of socio-educational practice in the Kalmenhof educational institution. Juventa Verlag, Weinheim / Munich 1988.

- ↑ In the annual review of the Kalmenhof from 1890 it is noted “Immediately after that conference, introductory steps were taken to establish an association for the feeble-minded and nonsensical”

- ↑ a b The home of death. In: Stern. No. 45/1987 IIIa / 2.

- ↑ Charity and social sentiment. In: Idsteiner Zeitung. February 1, 1988.

- ↑ a b community sheet of the Israelite community in Frankfurt. dated July 1936.

- ↑ The Israelite. dated March 22, 1928.

- ↑ Max Kirmsse on the homepage of the Max-Kirmsse-Schule ( memento of the original from November 6, 2010 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link has been inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ Günter Bangert, Thomas Zarda: 100 years of the Red Cross Idstein. German Red Cross Local Association Idstein, p. 32.

- ↑ The Aar-Bote reported on March 18, 1900 from an exhibition of the products at the exhibition for nursing in Frankfurt am Main

- ↑ a b Martin Wißkirchen: Idiot institution - remedial education institution - hospital. In: Christian Schrapper, Dieter Sengling (Hrsg.): The idea of formability - 100 years of socio-educational practice in the Kalmenhof educational institution. Juventa Verlag, Weinheim / Munich 1988, p. 106.

- ↑ Martin Wißkirchen: Idiot institute - remedial education institute - military hospital. In: Christian Schrapper, Dieter Sengling (Hrsg.): The idea of formability - 100 years of socio-educational practice in the Kalmenhof educational institution. Juventa Verlag, Weinheim / Munich 1988, p. 107.

- ↑ 100 years of Kalmenhof 1888–1988. from the Social Pedagogical Center Kalmenhof p. 7.

- ↑ 100 years of Kalmenhof 1888–1988. from the Social Pedagogical Center Kalmenhof pp. 5–20.

- ↑ Martin Wißkirchen: Idiot institute - remedial education institute - military hospital. In: Christian Schrapper, Dieter Sengling (Hrsg.): The idea of formability - 100 years of socio-educational practice in the Kalmenhof educational institution. Juventa Verlag, Weinheim / Munich 1988, p. 108.

- ^ Charles Graves: The Royal Ulster Rifles. vol. 3: 1919-1948. Times Printing, 1950, p. 10.

- ^ Günter Bangert, Thomas Zarda: 100 years of the Red Cross Idstein. German Red Cross Local Association Idstein, p. 69. Fritz (Friedrich) Klein (* 1863, † July 15, 1940 in Wiesbaden) held several offices: He was chief physician of the city hospital, doctor of the military hospital, chief physician at Kalmenhof, city councilor and chairman of the Nassau Medical Association.

- ^ General journal for psychiatry and psycho-forensic medicine. 1928, volume 91.

- ↑ Martin Wißkirchen: Idiot institute - remedial education institute - military hospital. In: Christian Schrapper, Dieter Sengling (Hrsg.): The idea of formability - 100 years of socio-educational practice in the Kalmenhof educational institution. Juventa Verlag, Weinheim / Munich 1988, p. 114.

- ↑ Martin Wißkirchen: Idiot institute - remedial education institute - military hospital. In: Christian Schrapper, Dieter Sengling (Hrsg.): The idea of formability - 100 years of socio-educational practice in the Kalmenhof educational institution. Juventa Verlag, Weinheim / Munich 1988, p. 120.

- ↑ Martin Wißkirchen: Idiot institute - remedial education institute - military hospital. In: Christian Schrapper, Dieter Sengling (Hrsg.): The idea of formability - 100 years of socio-educational practice in the Kalmenhof educational institution. Juventa Verlag, Weinheim / Munich 1988, p. 122.

- ↑ The memorial on Veitmühlenberg bears the following inscription: In memory of the victims of the tyranny. More than 600 children and adults from the Kalmenhof were murdered between 1941 and 1945. Many of the victims are buried here. The number and location of the individual graves are unknown.

- ↑ From "The Kalmenhof then and now" p. 12 and 13: According to the registry office 719 deaths, 358 deaths according to the Kalmenhof trial files, 292 deaths according to the house book, 201 deaths according to the Catholic register and the Protestant register 122 dead, according to the evangelical chronicle approx. 690 dead, according to the grave digger 556 dead. The information from the various sources must be supplemented and added up in some cases because the grave digger z. B. only counted the dead on the cemetery in Kalmenhof and the Catholic and Protestant death register only contains the dead who were church buried in the cemetery in Idstein. Therefore a number of more than 750 deaths must be assumed.

- ↑ In the main books of the Kalmenhof 45, in the still existing individual case files 37, in an overview of the German community assembly up to December 31, 1935 148. However, duplicate entries must be taken into account.

- ↑ Andrea Berger, Thomas Oelschläger: "I let you die a natural death." In: Christian Schrapper, Dieter Sengling (Ed.): The idea of imageability - 100 years of socio-educational practice in the Kalmenhof sanatorium. Juventa Verlag, Weinheim / Munich 1988, p. 292.

- ↑ Andrea Berger, Thomas Oelschläger: "I let her die a natural death." In: Christian Schrapper, Dieter Sengling (Ed.): The idea of imageability - 100 years of socio-educational practice in the Kalmenhof sanatorium. Juventa Verlag, Weinheim / Munich 1988, p. 303.

- ↑ 100 years of Kalmenhof 1888–1988. from the Social Pedagogical Center Kalmenhof p. 11.

- ↑ Andrea Berger, Thomas Oelschläger: "I let you die a natural death." In: Christian Schrapper, Dieter Sengling (Ed.): The idea of imageability - 100 years of socio-educational practice in the Kalmenhof sanatorium. Juventa Verlag, Weinheim / Munich 1988, p. 305.

- ↑ Großmann, 3rd day of the hearing: court files of the "Kalmenhof Trial" HSTA Wiesbaden, Dept. 461 No. 31526.

- ↑ Andrea Berger, Thomas Oelschläger: "I let you die a natural death." In: Christian Schrapper, Dieter Sengling (Ed.): The idea of imageability - 100 years of socio-educational practice in the Kalmenhof sanatorium. Juventa Verlag, Weinheim / Munich 1988, p. 308.

- ↑ Andrea Berger, Thomas Oelschläger: "I let you die a natural death." In: Christian Schrapper, Dieter Sengling (Ed.): The idea of imageability - 100 years of socio-educational practice in the Kalmenhof sanatorium. Juventa Verlag, Weinheim / Munich 1988, p. 310.

- ↑ Andrea Berger, Thomas Oelschläger: "I let you die a natural death." In: Christian Schrapper, Dieter Sengling (ed.): The idea of image - 100 years of socio-educational practice in the Kalmenhof. Juventa Verlag, Weinheim / Munich 1988, p. 314.

- ^ Idstein, "Kalmenhof" educational institution. Topography of National Socialism in Hesse. (As of January 26, 2011). In: Landesgeschichtliches Informationssystem Hessen (LAGIS).

- ↑ a b c Stone witnesses. ( Memento from April 12, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) In: Idsteiner Zeitung. April 8, 2011.

- ^ Search for the burial ground in FAZ of April 4, 2017, p. 40.

- ↑ Waste of money on idiots and drunkards. In: The time . April 25, 1986.

- ↑ Andrea Berger, Thomas Oelschläger: "I let you die a natural death." In: Christian Schrapper, Dieter Sengling (Ed.): The idea of imageability - 100 years of socio-educational practice in the Kalmenhof sanatorium. Juventa Verlag, Weinheim / Munich 1988, p. 315.

- ^ The prison doctors. In: Andreas Kinast: "The child cannot be trained ..." Euthanasia in the Waldniel children's department 1941–1943. SH-Verlag, Cologne 2010, p. 111.

- ^ Fritz Geisthardt: Idstein's story. In: Magistrat der Stadt Idstein: Idstein - Past and Present. 1987, p. 144.

- ↑ Andrea Berger, Thomas Oelschläger: "I let you die a natural death." In: Christian Schrapper, Dieter Sengling (Ed.): The idea of imageability - 100 years of socio-educational practice in the Kalmenhof sanatorium. Juventa Verlag, Weinheim / Munich 1988, p. 336.

- ↑ Andrea Berger, Thomas Oelschläger: "I let her die a natural death." In: Christian Schrapper, Dieter Sengling (Ed.): The idea of imageability - 100 years of socio-educational practice in the Kalmenhof sanatorium. Juventa Verlag, Weinheim / Munich 1988, p. 330.

- ^ Loni Franz example of moral courage. ( Page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. In: Idsteiner Zeitung. June 2, 2009.

- ↑ Everyone should know. ( Page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. In: Idsteiner Zeitung. November 17, 2009.

- ↑ Ekkehard Maaß: Silence - Forgetting - Remembering. In: Christian Schrapper, Dieter Sengling (Hrsg.): The idea of formability - 100 years of socio-educational practice in the Kalmenhof educational institution. Juventa Verlag, Weinheim / Munich 1988, p. 337.

- ^ Kerstin Freudiger: The legal processing of Nazi crimes. Mohr Siebeck Verlag, Tübingen 2002, ISBN 3-16-147687-5 , pp. 231-251.

- ↑ Rüter u. a .: Justice and Nazi crimes. Collection of German criminal convictions for Nazi homicide crimes 1945–1999. Volume 1 (1968).

- ↑ a b Ekkehard Maaß: Silence - Forgetting - Remembering. In: Christian Schrapper, Dieter Sengling (Hrsg.): The idea of formability - 100 years of socio-educational practice in the Kalmenhof educational institution. Juventa Verlag, Weinheim / Munich 1988, p. 343.

- ^ Richard von Premerstein: Max Kirmsse, a historian of the special school system. Life and work. In: Journal for curative education. Vol. 14 (1963), No. 12, pp. 688-695.

- ↑ Peter Wensierski on his homepage: Reports from the event in Idstein / Kalmenhof.

- ↑ Beatings for Picos . In: Der Spiegel . No. 47 , 1969 ( online ).

- ↑ Manfred Berger : Manfred Berger - the first academic kindergarten teacher, in: Irmgard Burtscher (Hrsg.): Handbuch für Erzieherinnen in crèche, kindergarten, daycare and after-school care center, edition 90, Munich 2016, p. 4.

- ↑ cf. Schölzel-Klamp / Köhler-Saretzki 2010, p. 88.

- ↑ Christian Schrapper, Dieter Sengling (ed.): The idea of imageability - 100 years of socio-educational practice in the Kalmenhof educational institution. Juventa Verlag, Weinheim / Munich 1988, p. 208.

- ↑ Christian Schrapper: From the educational home to the social pedagogical center - The Kalmenhof since 1968. In: Christian Schrapper, Dieter Sengling (ed.): The idea of education - 100 years of socio-educational practice in the Kalmenhof therapeutic institution. Juventa Verlag, Weinheim / Munich 1988, p. 195.

- ↑ Lutz Kaelber: Commemoration of the Nazi “Child Euthanasia” - two case studies (Eichberg, Kalmenhof) and general conclusions on the culture of commemoration. In: Working group for research into National Socialist "euthanasia" and forced sterilization (ed.): Give the victims their names: Nazi "euthanasia" crimes, historical-political responsibility and culture of remembrance. Klemm + Oelschläger, Münster 2011, p. 217.

- ↑ Volker Stavenow: Further excavations after georadar investigation at Kalmenhof The georadar investigation at Idsteiner Kalmenhof suggests something bad: There is a high probability that there are more graves of children and young people who were victims of the Nazi regime. In: Wiesbaden Courier. VRM, July 18, 2019, accessed December 6, 2019 .

- ↑ Ekkehard Maaß: Silence - Forgetting - Remembering. In: Christian Schrapper, Dieter Sengling (Hrsg.): The idea of formability - 100 years of socio-educational practice in the Kalmenhof educational institution. Juventa Verlag, Weinheim / Munich 1988, p. 353.

- ↑ End station Kalmenhof - a forgotten chapter of history. In: Idsteiner Zeitung. January 30, 1982.

- ↑ Sometimes the folding coffin served as a toy. In: Frankfurter Rundschau. 4th February 1982.

- ↑ Documentation of the horror. ( Page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. In: Idsteiner Zeitung. June 16, 2010.

- ↑ Administrative report 2008 of the city of Idstein ( page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (PDF)

- ↑ Hands destroy weapons ( page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. In: Idsteiner Zeitung. dated May 12, 2010.

- ^ ZDF documentary shows the suffering of German children in care. In: Focus Online . 4th March 2013.

- ↑ First stumbling block laid in the new old town In: Frankfurter Rundschau from May 9, 2018.

- ↑ On the future of the Kalmenhof. In: Idsteiner Woche. July 25, 1996.

- ↑ We hope for common sense. ( Page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. In: Wiesbadener Tagblatt. from May 25, 2011.

- ↑ Modern care in a modern house. In: Idsteiner Zeitung. July 14, 2004.

- ↑ Light tones ensure comfort. In: Idsteiner Zeitung. June 9, 2008.

- ↑ Smoke gas cloud over Idstein. ( Page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. In: Wiesbaden Courier. dated September 12, 2011.

- ↑ Message on the homepage of the University of Kassel from September 19, 2011: University of Kassel researches the history of the children's and youth homes of the LWV ( Memento of the original from March 4, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ New Vitos managing director. ( Page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. In: Wiesbadener Tagblatt of May 8, 2012.

- ↑ a b Volker Stavenow: Memorial for euthanasia in the Nazi era: Former Kalmenhof hospital is for sale In: Wiesbadener Tagblatt from 7 July 2016.

- ↑ Volker Stavenow: Vitos: No decision to sell the Idsteiner Kalmenhof Clinic yet In: Wiesbadener Tagblatt : from July 8, 2016.

- ↑ Ingrid Nicolai: Kalmenhof site: Parliament wants to exclude building on graves , Wiesbadener Kurier , July 16, 2016

- ↑ Joint application of the CDU, SPD, FWG, Bündnis 90 / Die Grünen and FDP regarding the framework agreement between the city of Idstein and the LWV and its companies on the Kalmenhof grounds , Council information system of the city of Idstein , July 14, 2016

- ^ Search for the burial ground in FAZ of April 4, 2017, p. 40.

- ↑ Waste of money on idiots and drunkards. In: The time . April 25, 1986.

- ↑ a b Remnants buried in Wiesbadener Kurier on October 28, 2019

- ↑ Idstein 1933-1945. of the history group of the Pestalozzi School Idstein in July 1998.

Coordinates

- ↑ 50 ° 13 ′ 5.4 ″ N , 8 ° 16 ′ 4 ″ E

- ↑ 50 ° 13 '10.3 " N , 8 ° 16'13.9" E

- ↑ 50 ° 13 '1.3 " N , 8 ° 16'7.9" E

Coordinates: 50 ° 13 ′ 7.8 " N , 8 ° 16 ′ 9.8" E