horseradish

| horseradish | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Horseradish ( Armoracia rusticana ) |

||||||||||||

| Systematics | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| Scientific name | ||||||||||||

| Armoracia rusticana | ||||||||||||

| G. Gaertn. , B.Mey. & Scherb. |

The horseradish ( Armoracia rusticana ), as a larger “ radish ” in Middle High German / Old High German mēr (“more”, “bigger”), belongs to the cruciferous family (Brassicaceae). The root of the horseradish plant is used as a vegetable , spice or in herbal medicine. It is not closely related to the radishes of the genus Raphanus .

Its original home is in Eastern and Southern Europe, where it is called Kren (also "Kre" and "Kreen"), such as B. in Bavaria, Austria, Slovakia, South Tyrol, Czech Republic etc. a. The word horseradish (from Old High German chrēn / krēn since the 13th century ) comes from the Slavic krenas , which means to cry . A Franconian variant is also written "Kree" according to the pronunciation. Another Franconian variant is the “Merch” in the Itzgründischen area. The name "Meerettig" is known in the Alemannic language area. Other names are "Mährrettig" or "Beißwurzel". "Steirischer Kren PGI " is a recognized designation of origin with regional protection and entered in the register of traditional foods .

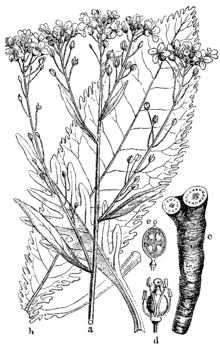

description

Vegetative characteristics

The horseradish grows as a perennial herbaceous plant and reaches stature heights of 50 to 120 centimeters, occasionally up to 2 meters. This hardy plant can withstand temperatures down to −50 ° C. A vertical, cylindrical taproot is formed as a permanent organ , which reaches a length of 30 to 40 centimeters and a diameter of 4 to 6 centimeters. Under good conditions with easily rootable soil (bog, sand) the taproot can grow up to 60 centimeters long. Towards the stem, the root is many-headed and at the end of the root branchy with many side roots and root fibers. The irregularly grooved root is dirty yellow-brown on the outside, but the inside is white and somewhat fibrous.

All parts of the plant are hairless. The basal leaves distributed on the stem are divided into a petiole and a leaf blade. The petiole, which is always clearly widened at its base, can be up to 60 centimeters long on the basal leaves, but it is very short on the uppermost leaves. The mostly simple, rarely pinnate leaf blade is oval-lanceolate on the basal leaves and linear-lanceolate on the upper stem leaves. The leaf blade is usually 20 to 45 (10 to 60) centimeters long and 5 to 12 (3 to 17) centimeters wide. The leaf margin is strongly notched on the basal leaves and somewhat wavy or curled up to the lower stem leaves and is almost smooth on the upper stem leaves. The leaf surfaces have strongly protruding nerves. The leaves on the stem are briefly divided below, often pinnate and with entire margins.

Generative characteristics

In the spring the inflorescences begin to form; the flowering period extends from mid-May to July. The round inflorescence shafts reach heights of up to 1.20 meters. The racemose inflorescence has a diameter of up to 40 centimeters. There are no bracts. The flowers smell strongly. The hermaphroditic flowers are fourfold with double perianth . The four elongated and blunt sepals are 2 to 4 millimeters long. The four white petals are nailed with mostly 5 to 7 (to 8) millimeters up to twice as long as the sepals and up to 1.5 millimeters long. There are six glands between the stamens, two on the sides of the base of the short stamen and one between the long stamens and the calyx. There are six stamens with 1 to 2.5 millimeter long stamens and 0.5 to 0.8 mm long anthers. The stylus is imperceptible or up to 0.5 millimeters long. The scar is hemispherical with a furrow on top.

The flower / fruit stalks grow to a length of 8 to 20 millimeters until the fruit is ripe. The pods do not always develop completely. The pod is 4 to 6 millimeters long. In each pod compartment there are no or four to rarely six seeds. The compressed-looking seeds are oval, brown and almost smooth.

Chromosome number

The number of chromosomes is 2n = 32.

Systematics

The species was first published in 1753 under the name Cochlearia armoracia by Carl von Linné in Species Plantarum . In 1800, Philipp Gottfried Gaertner , Bernhard Meyer and Johannes Scherbius set up the new genus Armoracia in the Economic-Technical Flora of the Wetterau and replaced the previous name with the name Armoracia rusticana, which is valid today . Different authors put this species in different genera. There are a number of synonyms for Armoracia rusticana P. Gaertn. , B. Mey. & Scherb. : Armoracia rusticana Baumg. , Cochlearia armoracia L. , Cochlearia rusticana Lam. , Cochlearia variifolia Salisb. , Raphanis magna Moench , Armoracia lapathifolia Gilib. , Armoracia sativa Bernh. , Nasturtium armoracia ( L. ) Fries , Rorippa armoracia ( L. ) Hitchc. , Rorippa rusticana ( G. Gaertner et al.) Godron . The three species counting genus Armoracia belongs to the tribe Cardamineae in the family Brassicaceae .

Origin of the German common name

There were different views on the origin of the word horseradish (from Middle High German merretich ). The plant name in its Old High German form can be traced back to the 10th century ( mērrātih ).

According to Heinrich Marzell , the name means "the radish that came to us from the sea". (For such motivation for naming, see also “sea onion” , “ guinea pig ” and “monkey” ). An indication of this interpretation is also the fact that horseradish grows on the coast of the sea. The opinion that horseradish originated from Mährrettich (from mare = old horse) (as in Adelung ) and thus corresponds to the English horseradish or the French radis de cheval , Marcell already considers an often occurring "learned folk etymology".

The etymological Duden gives as his source ( etymological dictionary of the German language ) the established view again that the actual word meaning simply a "bigger radish" (Latin raphanus maior ) - in contrast to the already longer known smaller radish - referred and, among others, Marcell's opinion represents a later reinterpretation. It should be noted that the use of more in the sense of “stronger” or “larger” (Latin maior ) has become less common since Middle High German, which is why other plausible constructions were sought.

The word horseradish , used in Austria and Bavaria as well as in Silesian for horseradish since the 13th century ( chrēn , krēn ) is a loan word from the Slavic-speaking area , where it finds its equivalent, for example Czech křen (older chřĕn ; a shortening of the word kořen = Root) or Slovak chren .

Occurrence and meaning

Horseradish grows wild on the edge of damp meadows, on streams and river banks. In Germany, the centers of horseradish cultivation are the Spreewald , Baden's Fautenbach , the Baden horseradish village Urloffen (which has its own horseradish song ) and the Franconian Baiersdorf , where there is also a horseradish museum . In the Bamberg and Nuremberg area, the cultivation of horseradish has been known since Charlemagne. In 1930, horseradish cultivation in the Franconian area between Nuremberg and Forchheim was considered the largest in the world. At that time, horseradish was hardly grown in the Netherlands. But it is also used for agriculture in the Hanover and Hamburg areas and in the Erfurt area.

In Austria, the traditional growing areas for horseradish are located in the southern and eastern Styrian districts of Hartberg-Fürstenfeld , Deutschlandsberg , Voitsberg , Leibnitz , Weiz , Graz-Umgebung and southeast Styria . Around 4,000 tons of horseradish are produced in Styria every year. The cultivation area is around 300 hectares . In France, in Alsace, there are now around 20 hectares that are cultivated with horseradish by 15 producers. In the United States, horseradish is grown commercially primarily in the states of Missouri, Illinois, New York, and New Jersey. There, too, it occurs overgrown by cultivation. South Africa also knows horseradish cultivation.

Origin and history

Horseradish was already known in ancient times . This is evidenced , for example, by a Pompeian mural. Cato dealt extensively with this plant in his treatises on agriculture. The horseradish originates from Moldova . From there it was brought to Central Europe and spread by the Slavic peoples. Today it occurs wild in Central Europe. In Eastern Russia and the Ukraine it still exists in its wild form.

In Germany, the horseradish is said to have only been grown since the Middle Ages. It is said to have been used first as a medicinal plant and only then as a spice. The designation "Steirischer Kren" has enjoyed EU protection since 2009 and is a protected geographical indication .

One of the first indications that the horseradish can also be found wild on its own comes from Leonhart Fuchs . He writes in the German edition of his herbal book (1543, Cap. CCLVI, under "Statt irer waxung"): " The horseradish grows in the wise at the time when it was planted in Tübingen when its vil was found on the Pfaffenwisen. He would also be grazed in the gardens, and the same is a little more milky and better, the wait and planting half the time ”. In the Latin edition (1542: page 661) it says: “ in pratis nonnumquam sua sponte copiose provenit, ut fit in prato ad oppidum Tubingam sito, sacrificorum vocato ”. As a wild plant, the horseradish comes up with the good Heinrich ( Blitum bonus-henricus ) and with nettle species ( Urtica ) in societies of the Arction or Aegopodion associations. In the Allgäu Alps, the horseradish rises as a wild plant at the Prinz-Luitpold-Haus in Bavaria up to 1,847 m above sea level.

The cultivation of horseradish in North America goes back to plants harvested in the Spreewald and shipped in boxes and barrels. A project of the EU Commission has been running since 2010, in which the marketing and sales of "Bavarian Horseradish" is promoted under the term World Pleasure Heritage Bavaria .

use

Cultivation

There are no special varieties of horseradish, but local origins (ecotypes) with their own selections have developed over the centuries of commercial cultivation. Root shape and taste differ. Horseradish needs easy-to-root and easy-to-work, deep soils that allow straight growth and easy harvesting of the roots. That is why it has particularly spread in Germany in areas such as Nuremberg (loamy sand) and Baden (loess and sandy alluvial soil).

Fertilization with 40 to 50 t / ha of manure works better in autumn if it is plowed in. The soil must not be freshly fertilized with manure before planting. The necessary amount of nitrogen (N) can also be given in 2 applications as top dressing with 20-25 kg N / ha each. A pH of 6 to 7 is considered to be the ideal pH range for the soil reaction. The total requirement, from which the soil supply and manure fertilization is deducted, is 220 N, 65 P 2 O 5 , 275 K 2 O, 25 MgO and 190 CaO in kg / ha . Horseradish is sensitive to high levels of salt in the soil, which is why organic fertilization is preferable.

It is best to plant side roots (Fechser or Fexer and Schwigatze in the Spreewald). For this purpose, about 6 to 8 mm thick and partly 30 or 50 to 60 cm long Fechser selected mother plants are used, which arise from the harvest in autumn from fully grown horseradish stalks. The fechser are planted in late March to April or in autumn (November). The roots are placed diagonally in prepared trenches or pushed into pre-punched diagonally running holes with a long piece of wood. If they are placed too horizontally, the roots will hardly grow in thickness, if they come too steeply into the ground, they will grow too much into the weed. The special wood, which is slightly curved and partly shod with iron, is 50 centimeters long and is called a Kreenstecher.

Today a special planting machine is used for planting. The plant spacing is 25 centimeters in the row, the row spacing 50-60 centimeters. The roots are covered with soil, but not covered, with the heads about 2–3 centimeters above the soil. Ridge cultivation is also possible and is now standard in commercial cultivation. Three to four weeks after planting, the cuttings (fechers) sprout.

In the course of the culture, the rhizomes were previously dug or raised in order to remove the lateral roots and thus promote the growth of the strongest roots. This happened in June and resulted in large and compact roots. Removing the side roots also increases the yield because more roots of marketable quality can be harvested. If this is not done, the proportion of A-goods drops from 90 to 40 percent. At the same time, however, root diseases are promoted.

The main growth of the culture extends to the later summer, which is why the culture should be watered and fertilized especially during this phase, if necessary. Apart from the irrigation, only the weeds are controlled throughout the year. If the roots are still too weak for harvest in the home garden, individual plants can also be left in the ground and harvested the following year. This is not common in commercial crops. However, in order to harvest particularly thick stalks, the whole crop can also stand for two years without a harvest.

harvest

Harvest can begin when the leaves begin to die. Then the root growth is finished. Since horseradish is hardy, the harvest can take place from autumn from the end of October to spring before the rootstocks are driven out again.

Harvesting is carried out with a potato harvester that is more robust thanks to its reinforcements and drives 40 centimeters below the rows. In this way, the side roots, which are prepared as cut pieces for Fechser, can also be picked up without damage. If another crop is to follow afterwards, all roots must be removed when harvesting, otherwise horseradish will become a weed.

A yield of 20 tons / ha is expected, which corresponds to around 30,000 stalks. The yield, however, fluctuates between 5.6 and 30.6 t / ha depending on the planting density (2–4 Fechser / m²) and low to high fertilization. If the harvest is carried out in August, only half the yield potential can be used because the greatest increase in yield occurs in October.

Since horseradish is easy to store, it can be transported and sold over long distances. For sale as fresh it is washed and wrapped in foil to prevent it from drying out. However, the largest part goes into processing as industrial goods. Depending on the mechanization, 800 to 1000 working hours per hectare are required for cultivation.

Multiplication

Since horseradish does not produce enough seeds, it is not usual to propagate it by sowing. For propagation, pieces of root or adventitious roots are separated and stuck. The adventitious roots must not be bumpy or crooked, otherwise horseradish types with low-quality roots will be bred by selection for a long time.

The root pieces, also called fechser, are about as thick as a pencil. They are stored in bundles in cool damp sand in winter and planted in April. The crown pieces (head of the root) are less suitable for propagation. To do this, the top 5 cm of the smaller bars are cut off. Fechser and heads can be driven for faster rooting.

Diseases and pests

Pests include mice and grubs that eat at the roots, as well as horseradish leaf beetles and their larvae. The latter, like the horseradish fleas and the yellow-black striped fleas, cause pitting and can destroy the entire foliage in the event of severe infestation. The beet sawfly ( Athalia spinarum ) also occasionally causes so-called space mines by eating under the leaf surface. Cabbage butterfly , horseradish tensioner ( Larentia fluctuata ) and evergestis forficalis ( evergestis forficalis ) are encountered less. Among the fungal diseases, Ascochyta armoraciae and Cercospora armoraciae should be mentioned. In addition, come white rust ( Albugo candida ), often simultaneously with downy mildew occurs before. Infestation by the fungus Verticillium dahliae does not reduce the yield, but leads to the roots turning black, which makes them worthless in commercial cultivation. Due to the vegetative propagation of the seedlings, crop failures of up to 100% occurred in individual farms.

Fresh manure fertilization in spring can lead to blotchy roots. This is the blackness of horseradish , which is probably physiological. The vegetative reproduction easily leads to the reproduction of virus-contaminated seedlings. The virus that causes the filamentous peeling is known. Other viral diseases in horseradish are aphid-transmitted horseradish mosaic virus ( Turnip mosaic virus ), which also causes the cabbage black ring spots . Moreover, even the coming Arabis mosaic virus (arabis mosaic virus) and the Tomato Black Ring Virus (tomato black ring virus) before.

use

kitchen

Especially in the horseradish growing areas, dishes with horseradish are part of everyday life. The horseradish root is odorless in its unprocessed state. If it is cut or rubbed, it gives off a pungent and tear-irritating odor. Responsible for this is allyl isothiocyanate , the reaction to cell damage enzyme atic from Sinigrin forms. Before pepper was readily available , horseradish and mustard were the only hot spices in German cuisine and were accordingly widely used. If the root is dried or cooked, it loses most of its volatile oil and, with it, its pungent taste.

The Englishman John Gerard reported in 1597 that “the mashed horseradish, mixed with a little vinegar, was popular with the Germans for sauces with fish dishes and for dishes that we eat with mustard”. Horseradish is today among other things, smoked fish , boiled beef , sour meat , roast beef to ham and Frankfurt or Vienna sausage served. Quark or cream cheese seasoned with horseradish is a popular spread. Horseradish with cream is often prepared as cream horseradish.

Other types of preparation are horseradish mustard or cranberry cream horseradish, which is used with game, and apple horseradish , which is particularly widespread in the Bavarian and Austrian regions , as well as bread roll, the classic accompaniment to cooked beef such as boiled beef. Horseradish cream also goes well with steamed fish. In addition to being used raw, horseradish is also used cooked. It finds its place on the menus in Franconia and Hesse as well as in Lausitz as a horseradish sauce with cooked beef.

The side roots and, in spring, the young green shoots of horseradish can also be used. The shoots can be sautéed in the pan and eaten as a vegetable snack. The side roots can be cut into slices, poured with boiling water, left to stand for ten minutes and drunk as horseradish tea.

ingredients

Horseradish contains, among other things, the following ingredients: vitamin C , vitamins B1 , B2 and B6 , potassium , calcium , magnesium , iron and phosphorus as well as the mustard oil glycosides sinigrin and gluconasturtiin , allicin , flavones , essential oils from which mustard oils are formed, which are among other things antibiotic Act.

The vitamin C content of the fresh plant is 177.9 mg / 100 g fresh weight. Allyl or butyl mustard oil is mainly responsible as a flavor and odor carrier and irritates to tears. They are contained in the fresh root up to a level of 0.05%. In addition, the mustard oils methyl, ethyl, isopropyl, 4-pentenyl, 2-phenylethyl isothiocyanate and ethyl thiocyanate were found. When the cells are destroyed, the myrosinase enzyme acts on the glycoside sinigrin, a precursor to mustard oil, and creates mustard oil. Other ingredients are asparagine, glutamine, arginine, organically fixed sulfur and the enzyme peroxidase (horseradish peroxidase, or HRP for short).

storage

The roots are harvested in autumn, freed from root fibers, side roots and excess soil and pounded into damp sand. In commercial crops, the roots are packed in plastic bags or bags, stored in the cold room at −2 ° C and are therefore ready for delivery for a long time after the harvest and will last until the next harvest. Storage tests showed that a storage temperature of down to −5 ° C is recommended. The roots become rubbery and tough at lower temperatures. During storage, the roots slowly lose their sharpness, which is most intense immediately after harvest. Some of the roots remain in the field over winter and are harvested in spring. The soil serves as a natural bed. During this time the roots do not grow any further and do not lose quality.

Medical importance

In the Middle Ages there was a whole list of diseases against which horseradish was administered (pharmacologically in the same way as the radish, which is considered to be somewhat weaker). It was mainly used as an irritant, reddening agent and used against scurvy. Horseradish was used more externally than internally. In addition, horseradish was eaten in large quantities as a poisoning agent to encourage vomiting. It was also used like mustard against indigestion, scurvy , dropsy , amenorrhea and intermittent fever . For this purpose, the root was rubbed or pressed and administered spoon-wise. It was also considered useful for earache and three-day fever.

Nowadays, horseradish is used to strengthen the body's defenses and protect against colds. The horseradish contains a lot of vitamin C. Radix Armoraciae, which can be bought in pharmacies, is contained in remedies for flu and urinary tract infections. It stimulates the circulation, relieves cough and is used externally as a poultice for rheumatism , gout , insect bites, sciatica and other nerve pain. It should also help with headaches. To do this, you have to inhale a little scent of the grated horseradish, which relieves slight tension. Horseradish is also said to be effective against gastrointestinal disorders and has a beneficial effect on the secretion of bile juice (fat digestion). Horseradish also contains bacteria-inhibiting (antibiotic) and cancer-preventing substances. These are sulfur-containing substances that are also found in garlic (such as allicin , sinigrin ) and make horseradish a very healthy spice .

The antimicrobial effect of the so-called mustard oils in horseradish has been scientifically proven . The essential oil contains allyl mustard oil (approx. 90%) and 2-phenylethylene mustard oil. Depending on the dose, the horseradish has a bacteriostatic or bactericidal effect. For mustard oil extraction, not the perennial, but only the underground thick-fleshed roots of the horseradish are used.

The antimicrobial effect of volatile and oily active ingredients from horseradish could already be determined in the 1950s. In-vitro tests have shown that the entire oil has a strong bacteriostatic effect: the allyl mustard oil from the horseradish root shows good effectiveness in the gram-negative spectrum, while the 2-phenylethylene mustard oil has an extended spectrum of action in the gram-positive range.

An anti- viral effect of mustard oil from horseradish could also be proven. Horseradish oil also has a fungistatic effect on human pathogens, yeasts, sprouts and molds.

Various studies have shown that horseradish oil has a detoxifying effect on streptococcal and staphylococcal infections, which can be explained by the inactivation or destruction of the streptococcal toxin streptolysin O. As early as 1963, investigations at the Gießen Institute for Hygiene showed that approx. 100 mg of the plant contained the amount of active ingredient that would be required to inactivate three times the amount of staphylococcus toxin that was previously found to be the highest toxin concentration in the human organism.

Horseradish root is indicated for catarrh of the respiratory tract, infections of the lower urinary tract and for hyperaemic treatment in mild muscle pain (external use). The fresh or dried, comminuted drug, the fresh plant juice or other galenic preparations for ingestion or external use are used. A combination of the horseradish root with other plant substances makes sense. Combined with nasturtiums , the horseradish root is used in practice as a phytotherapeutic agent to treat respiratory and urinary tract infections. Numerous in vitro studies show that a combination of the two plant substances has a broad spectrum of antibacterial activity against 13 clinically relevant bacterial strains, including a. against MRSA and Pseudomonas aeruginosa and also has anti-inflammatory effects In the S3 guideline for the treatment of uncomplicated urinary tract infections , updated in 2017 , the use of medicinal products with nasturtiums and horseradish is recommended as a herbal treatment option for frequently recurring bladder infections .

It used to be assumed that horseradish should not be eaten if you have bladder or kidney problems, as large amounts of horseradish could cause kidney bleeding. This problem is no longer reported in today's specialist literature. Horseradish is not suitable for patients with stomach or intestinal ulcers or thyroid dysfunction .

When grated raw, horseradish can sting your mouth and nose, cause redness and blisters on the skin and, if taken in large quantities, cause diarrhea or vomiting. This property is lost when the horseradish root dries up.

Superstition

Horseradish is said to have healing powers as an amulet - in the past, children in the country often wore a necklace made from cut, threaded slices of a horseradish root. If you put a slice of raw horseradish in your wallet, it should never be empty.

See also

literature

- Anne Iburg: Dumont's little spice dictionary: origin, taste, use, recipes. DuMont-Mont, Cologne 2002, ISBN 3-8320-8780-X .

- Tai-yien Cheo, Lianli Lu, Guang Yang, Ihsan Al-Shehbaz, Vladimir Dorofeev: Brassicaceae in der Flora of China , Volume 8, 2001, p. 86: Armoracia rusticana - Online. (Section description and systematics)

- Ihsan A. Al-Shehbaz, John F. Gaskin: Brassicaceae in der Flora of North America , Volume 7, 2010, p. 559: Armoracia rusticana - Online. (Section description and systematics)

- Leonhart Fuchs New Kreüterbuoch in which nit alone gantz histori ... . Michael Isingrin, Basel 1543. Reprint: Konrad Kölbl, Munich 1964.

- Leonhart Fuchs: De Historia stirpium commentarii insignes ... M. Isingrin, Basel 1542. (Reprint: University Press, Stanford 1999, ISBN 0-8047-1631-5 ).

Web links

- Horseradish. In: FloraWeb.de.

- Distribution map for Germany. In: Floraweb .

- Armoracia rusticana P. Gaertn. & al. In: Info Flora , the national data and information center for Swiss flora . Retrieved October 27, 2015.

- Distribution in the northern hemisphere according to: Eric Hultén , Magnus Fries: Atlas of North European vascular plants 1986, ISBN 3-87429-263-0

- Thomas Meyer: Data sheet with identification key and photos at Flora-de: Flora von Deutschland (old name of the website: Flowers in Swabia )

- Kitchen lore: horseradish.

- Ingredients of horseradish.

- Armoracia rusticana inthe IUCN 2013 Red List of Endangered Species . Posted by: Smekalova, T. & Maslovky, O., 2010. Retrieved May 3, 2014.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Bavarian National Cookbook from 1824 , on kochrezepte.org, accessed on April 11, 2017

- ^ Friedrich Kluge , Alfred Götze : Etymological dictionary of the German language . 20th edition. Edited by Walther Mitzka , De Gruyter, Berlin / New York 1967; Reprint (“21st unchanged edition”) ibid 1975, ISBN 3-11-005709-3 , p. 403 f.

- ↑ Steirischer Kren PGI on Styrian specialties accessed on January 17, 2018

- ↑ a b c d e f D. FL von Schlechtendal: Illustration and description of all plants listed in the Pharmacopaea borussica , Volume 1, editor Friedrich Guimpel , Berlin, 1830, pp. 56–57.

- ↑ a b c H. Buchter-Weissbrodt: Horseradish - Vegetables, Pleasure, Health. In: Vegetables, No. 3, Ulmer Verlag, Stuttgart, 2003, p. 68.

- ↑ a b c Steirischer Kren PGI ( Memento of the original from June 16, 2010 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link has been inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (PDF) Council Regulation (EC) No. 510/2006 on the protection of geographical indications and designations of origin for agricultural products and foodstuffs.

-

↑ Styrian horseradish PGI . Entry no. 55 in the register of traditional foods of the Austrian Federal Ministry for Agriculture, Regions and Tourism .

Styrian horseradish PGI at the Genuss Region Österreich association . - ↑ a b J. beef Hoven: The vegetable production in fields and gardens , publishing house Eugen Ulmer, Stuttgart, 1919, pages 85-86.

- ↑ a b U. Gerhardt: Spices in the food industry - properties, technologies, use . 2nd Edition. Behr's Verlag, Hamburg 1994, ISBN 3-86022-202-3 .

- ↑ a b Vilmorin-Andrieux & Cie, Les Plantes Potagères, Quatrième Édition, 1925, pp. 641–642.

- ↑ a b c d e f G. Vogel, Handbuch des Spezial Gemüsebau, Meerrettich 1996, pp. 381–390, ISBN 3-8001-5285-1 .

- ↑ a b Erich Oberdorfer : Plant-sociological excursion flora for Germany and neighboring areas . 8th edition. Page 459. Stuttgart, Verlag Eugen Ulmer, 2001. ISBN 3-8001-3131-5

- ↑ Carl von Linné: Species Plantarum 2, 1753, p. 648, biodiversitylibrary.org .

- ↑ Tai-yien Cheo, Lianli Lu, Guang Yang, Ihsan Al-Shehbaz & Vladimir Dorofeev: Brassicaceae in der Flora of China , Volume 8, 2001, p. 86: Armoracia rusticana - Online. .

- ^ Armoracia in the Germplasm Resources Information Network (GRIN), USDA , ARS , National Genetic Resources Program. National Germplasm Resources Laboratory, Beltsville, Maryland.

- ^ Gerhard Köbler : Pocket dictionary of the old high German vocabulary . Schöningh Verlag, 1994, p. 232 (= UTB 1823): "meriratih, meriretih, merratih".

- ^ Friedrich Kluge , Alfred Götze : Etymological dictionary of the German language . 20th edition. Edited by Walther Mitzka . De Gruyter, Berlin / New York 1967; Reprint (“21st unchanged edition”) ibid 1975, ISBN 3-11-005709-3 , p. 470.

- ↑ MORE, adj. and adv.. In: Jacob Grimm , Wilhelm Grimm (Hrsg.): German dictionary . tape 12 : L, M - (VI). S. Hirzel, Leipzig 1885 ( woerterbuchnetz.de ).

- ↑ Friedrich Kluge, Alfred Götze: Etymological dictionary of the German language. 1975, p. 403 f.

- ↑ a b J. C. Döll: Flora of the Grand Duchy of Baden . Volume 3. Verlag G. Braun'sche Hofbuchhandlung, Karlsruhe 1862, pp. 1302–1303.

- ↑ JC Röhling, WDC Koch: Germany's flora . Volume 4. Friedrich Wilmans Verlag , Frankfurt am Main 1833, pp. 567-568.

- ↑ S. Brother: Horseradish has felt at home in Fautenbach for many years . Baden Online - October 29, 2008, accessed on November 13, 2008, Horseradish has felt at home in Fautenbach for many years .

- ↑ a b c d e f M. Fries: Handbook of practical agriculture , self-published by M. Fries, Dedheim, Schell'sche Buchdruckerei, Heilbronn, 1850, pp. 403-406.

- ↑ a b c d e L. Müllers et al .: Vegetable growing - A handbook and textbook for horticultural practice . XVI. The horseradish (Mährrettich, horse radish), horseradish . H. Rillinger Verlagsgesellschaft, Nordhausen am Harz, approx. 1937, p. 439.

- ↑ F. Schultheiss: Journal The Nutrition of Plants , March 1, 1931, p. 105

- ↑ CH Claassen, JG Hazelloop: Leerboek voor de Groententeelt . Deel I: De Teelt in full grond . 8th edition. Uitgevers-Maatschappij WEJ Tjeenk Willink, Zwolle 1931, pp. 308-310.

- ↑ a b c d e f J. Becker-Dillingen: Handbook of the entire vegetable cultivation , 1950, pp. 398-405.

- ↑ Steirischer Kren is protected from origin in the EU , ORF.at - March 2, 2009, accessed on December 26, 2009, steiermark.orf.at .

- ↑ C. Reibel: Le raifort, legume de niche . In: Fruit et Légume, 2006

- ^ A b H. C. Thompson: Vegetable Crops , 4th Edition, McGraw-Hill Book Company, New York, 1949, 348-349

- ^ Armoracia in the Germplasm Resources Information Network (GRIN), USDA , ARS , National Genetic Resources Program. National Germplasm Resources Laboratory, Beltsville, Maryland. Retrieved July 20, 2017.

- ↑ Erhard Dörr, Wolfgang Lippert : Flora of the Allgäu and its surroundings. Volume 1, IHW, Eching 2001, ISBN 3-930167-50-6 , p. 582.

- ^ H. Jentsch: Spreewälder Meerrettich. In: Natur und Landschaft , Heft 11, Cottbus, NLBC, 1989.

- ↑ a b c d e J. Reinhold: Advice for the cultivation of fine vegetables in the field. 1962, p. 410.

- ↑ a b U. Bomme: Culture Guide for Meerrettich , 2nd edition, Bavarian State Institute for Natural Resources and Life Sciences, Freising-Munich, 1990, pp. 1-4, ISSN 0932-5158 .

- ↑ a b F. Keller et al .: 100 Vegetables - Meerrettich , 1986, pp. 86-87, ISBN 3-906679-01-2 .

- ↑ a b F.-K. Helmholz: A lot of manual work still required - horseradish cultivation in the Spreewald. In: Monatsschrift, No. 2, 2006, pp. 90–92

- ^ J. Beckmann: Principles of German Agriculture , 4th Edition, Johann Christian Dieterich, Göttingen, 1790, p. 221.

- ↑ a b R. Schneider: Funke the name says it all - special company for horseradish cultivation Wilfried Funke in Adelsdorf / Neuhaus. In: Vegetables, No. 10, Ulmer Verlag, Stuttgart, 2006, pp. 12-14.

- ↑ a b R. Schneider: Margas "Kren" . In: Vegetables , No. 10, Ulmer Verlag, Stuttgart 2006, pp. 16 + 17.

- ↑ a b c K. Reichelt and N. Nicolaisen: Die Praxis des Gemüsebaues - instruction and manual for the practical grower and for use in educational establishments , Paul Parey publishing house, Berlin, 1931, pp. 204–205.

- ↑ a b J. E. von Reider: The description, culture and use of all spices and medicinal plants that grow wild in Germany and are to be cultivated outdoors ... Jenisch and Stage'sche Buchhandlung, Augsburg 1838, pp. 124–125.

- ↑ a b c I. H. Meyer: The rational plant production - the useful and commercial plants - their culture, properties, use and application . Verlag Ferdinand Enke, Erlangen 1859, pp. 381-385.

- ↑ a b N. N .: Danish horseradish variety with virus resistance - Sweden's largest horseradish company . In: Vegetables from: Viola-Trädgårdsvärlden 20. No. 3, 2007, Ulmer Verlag, Stuttgart, p. 38.

- ↑ U. Kraxner, J. Weichmann and D. Fritz: How should horseradish be fertilized? - Several years of trials answer the question. In: Vegetables, No. 9, Ulmer Verlag, Stuttgart, 1986, pp. 363-364.

- ↑ H. Nebel, J. Weichmann and D. Fritz: Yield of different horseradish origins - results of a research program for the processing industry. In: Vegetables, No. 6, Ulmer Verlag, Stuttgart, 1988, pp. 272-273.

- ^ HW Pabst: Textbook of Agriculture , 5th edition, Verlag W. Baumüller, Vienna, 1860, pp. 523-524.

- ↑ R. Ulrich: Leaf spots by Cercospora armoraciae on horseradish. In: Vegetables, No. 12, Ulmer Verlag, Stuttgart, 2006 p. 64.

- ^ S. Alan Walters & Elizabeth A. Wahle (2010): Horseradish Production in Illinois. HortTechnology vol. 20 no.2: 267 - 276.

- ↑ Reiner Krämer, Paul Scholze, Frank Marthe, Ulrich Ryschka, Evelyn Klocke, Günter Schumann (2003): Improving the disease resistance of cabbage vegetables: 1. Turnip mosaic virus (TuMV). Healthy Plants 55 (7): 193-198.

- ↑ a b F. Oesterlen: Textbook of drug theory . 5th revised edition. Laupp & Siebeck printing company, Tübingen 1853, p. 589.

- ^ J. Gerarde: The Herball, or General Historie of Plantes , Verlag J. Norton, London, 1597, pp. 186-188.

- ^ Sophie Wilhelmine Scheibler : German cookbook for all stands ... , Verlag CF Amelang, Leipzig & Berlin, 1866, p. 49.

- ↑ M. Schandri: Regensburger Kochbuch: 1000 original cooking recipes based on forty years of experience, initially for the bourgeois kitchen , Verlag A. Coppanrath, 1868, pp. 96-97.

- ↑ Land creates life

- ↑ J. Giolbert and HE Nursten: Volatile constituents' of horseradish roots In: Journal Science, Food and Agriculture, Vol 23, 1972 pp 527-539.

- ↑ H. Schirmer and B. Tauscher: Long-term storage of horseradish at different temperatures . In: Vegetables , No. 7, Ulmer Verlag, Stuttgart 1999, pp. 449-450.

- ↑ Land creates life

- ↑ Gundolf Keil: "blutken - bloedekijn". Notes on the etiology of the hyposphagma genesis in the 'Pommersfeld Silesian Eye Booklet' (1st third of the 15th century). With an overview of the ophthalmological texts of the German Middle Ages. In: Specialized prose research - Crossing borders. Volume 8/9, 2012/2013, pp. 7–175, here: pp. 113–120.

- ↑ R. Buchheim: Handbuch der Heilmittelellehre . 5th revised edition. Verlag Leopold Voss, Leipzig 1856, pp. 456–457.

- ↑ a b Heinz Schilcher (Ed.): Guideline Phytotherapy , Verlag Urban & Fischer, Munich 2016, pp. 220-221.

- ↑ a b A. G. Winter: Antibiotic therapy with medicinal plants . In: Planta Med , 3, 1955, pp. 1-16.

- ↑ a b M. Kienholz, B. Kemkes: The antibacterial effect of essential oils from horseradish root , Arzneimittel.-Forsch./Drug Res., 10, 1960, p. 917 ff.

- ↑ a b A. G. Winter, M. Hornbostel: Studies on antibiotics in higher plants . In: Naturwissenschaften , 40, 1953, p. 488 ff.

- ↑ P. Klesse, P. Lukoschek: Studies on the bacteriostatic effectiveness of some mustard oils . In: Arzneimittel.-Forsch./Drug Res. , 5, 1955, p. 505 ff.

- ↑ a b T. Halbeisen: An antibiotic substance from Cochlearia Armoraciae . In: Arzneimittel.-Forsch./Drug Res. , 7, 1957, pp. 321-324.

- ↑ AG Winter: The importance of essential oils for the treatment of urinary tract infections . In: Planta Med , 6, 1958, p. 306.

- ↑ AG Winter and L. Rings-Willeke: Studies on the influence of mustard oils on the multiplication of the influenza virus in exembryonated hen's eggs , Archive for Microbiology, Vol. 31, 1958, p. 311 ff.

- ↑ M. Kienholz: Influence of bacterial toxins by chamomile and horseradish ingredients . In: Arzneimittel.-Forsch./Drug Res. , 13, Issue 9-12 (series of publications), 1963.

- ↑ A. Conrad et al .: In-vitro studies on the antibacterial effectiveness of a combination of nasturtium herb (tropaeoli majoris Herba) and horseradish root (Armoraciae rusticanae radix) , Drug Res 56/12, 2006, pp. 842-849.

- ↑ A. Conrad et al .: Broad antibacterial effect of a mixture of mustard oils in vitro , Z Phytotherapy 29, Suppl. 1, 2008, pp. S22-S23.

- ↑ V. Dufour et al .: The antibacterial properties of isothiocyanates. In: Microbiology 161: 229-243 (2015)

- ↑ A. Borges et al .: Antibacterial activity and mode of action of selected glucosinolates hydrolysis products against bacterial pathogens. In: J Food Sci Technol , 52 (8), pp. 4737-48 (2015)

- ^ A. Marzocco et al .: Anti-inflammatory activity of horseradisch (Armoracia rusticana) root extracts in LPS-stimulated macrophages. In: Food Func. , 6 (12), pp. 3778-88 (2015)

- ↑ H. Tran et al .: Nasturtium (Indian cress, Tropaeolum majus nanum) dually blocks the COX an LOX pathway in primary human immune cells. In: Phytomedicine 23: 611–620 (2016)

- ↑ ML Lee et al .: Benzyl isothiocyanate exhibits anti-inflammatory effects in murine macrophages and in mouse skin. In: J Mol Med , 87, pp. 1251-1261 (2009)

- ↑ S3 guideline uncomplicated urinary tract infections - update 2017 (PDF) interdisciplinary S3 guideline "Epidemiology, diagnosis, therapy, prevention and management of uncomplicated, bacterial, community-acquired urinary tract infections in adult patients", AWMF register no. 043/044

- ↑ D. Frohne, H. Braun: Heilpflanze Lexikon . 7th edition. Scientific publishing company, 2002

- ↑ T. Dingermann, D. Löw: Phytopharmakologie , Wissenschaftliche Verlagsgesellschaft mbH, 2003.

- ↑ H. Wagner, M. Wiesenauer: Phytotherapy . 2nd Edition. Scientific publishing company, 2003.

- ↑ a b F. L. Strumpf: Handbook of Drug Science , 2nd Volume. Published by Th.CF Enslin, Berlin 1849, pp. 24-27.

- ↑ a b A. B. Lessing: Practical drug theory - manual of the special practical drug theory . 8th revised edition. A. Förstner'sche Buchhandlung, Berlin 1863, pp. 76-77.

- ↑ a b J. K. Crellin, J. Philpott, ALT Bass: Herbal Medicine Past and Present: A reference guide to medicinal plants . Duke University Press, 1990, ISBN 0-8223-1019-8 , pp. 252-254.

- ^ CL Willdenow, DHF Link: Herbalism to lectures . 7th edition. Haude & Spener'schen Buchhandlung, Berlin 1831, p. 331.